The Role of Emotion Regulation as a Potential Mediator between Secondary Traumatic Stress, Burnout, and Compassion Satisfaction in Professionals Working in the Forced Migration Field

Abstract

1. Introduction

Hypothesis

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

- The Professional Quality of Life Scale (ProQOL) [22,61]. The ProQOL is intended for use as a screening tool for the positive and negative aspects of working within a helping profession. It consists of three subscales: compassion satisfaction, secondary traumatic stress, and burnout, with the latter two subscales reflecting components of the construct of compassion fatigue. As mentioned above, in line with Cieslak et al. [21], in this study, the secondary traumatic stress was assumed as an independent construct from the compassion fatigue and was not measured with the ProQOL scale. For the purposes of the present study, therefore, we chose to administer only the scales measuring the compassion satisfaction (10 items) and the burnout (10 items) for a total of 20 items out of a total of 30 items. Participants were asked to respond to each item on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). Higher scores indicate higher levels of compassion satisfaction and burnout. In our sample, the Cronbach’s α were 0.877 for the compassion satisfaction scale 0.663 for burnout.

- The Secondary Traumatic Stress Scale (STSS) [62,63]. The Italian version of the STSS is a 15-item self-report that assesses frequency of intrusion (six items) and arousal (nine items) symptoms associated with secondary traumatic stress. Respondents were asked to report how frequently in the past 7 days they had experienced each item on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). Higher scores indicate greater levels of intrusion and arousal, and secondary traumatic stress. In our sample, the Cronbach’s α were 0.884 for the arousal, 0.771 for intrusion, and 0.903 for the total score of STSS.

- The Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS) [45,64] assesses individual differences in trait emotion dysregulation. The Italian version of the DERS consists of 36 items. For each item, participants were asked to indicate how often a particular statement applied to them on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). Scores on the DERS reflect levels of emotion dysregulation across six domains: (a) non-acceptance of emotional responses, (b) difficulties engaging in goal-directed behavior when distressed, (c) difficulties controlling impulsive behavior under negative emotional arousal, (d) poor emotional awareness, (e) limited access to effective emotion regulation strategies, (f) poor emotional clarity. Higher scores indicate greater levels of emotion dysregulation. In our sample, the Cronbach’s α was 0.942.

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arthur, N.; Ramaliu, A. Crisis intervention with survivors of torture. Crisis Interv. Time Ltd. Cogn. Treat. 2020, 6, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessitore, F. The Asylum Seekers Photographic Interview (ASPI): Evaluation of a new method to increase Nigerian asylum seekers’ narrative meaning-making after trauma. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2022, 14, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troisi, G.; Margherita, G.; Caffieri, A. Migrant women and gender-based violence: Focus group with operators. J. Prev. Interv. Community 2020, 50, 286–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, M.; Wong, J.; Trlin, A. Civic and social integration: A new field of social work practice with immigrants, refugees and asylum seekers. Int. Soc. Work. 2006, 49, 345–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leo, A.; Cotrufo, P.; Gozzoli, C. The Refugee Experience of Asylum Seekers in Italy: A Qualitative Study on the Intertwining of Protective and Risk Factors. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2022, 24, 1224–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franks, W.; Gawn, N.; Bowden, G. Barriers to access to mental health services for migrant workers, refugees and asylum seekers. J. Public Ment. Health 2006, 6, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, G.; Burck, C.; Roncin, L. Therapeutic activism: Supporting emotional resilience of volunteers working in a refugee camp. Psychother. Politics Int. 2020, 18, e1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leo, A.; D’Adamo, G.; Morozzi, C.; Gozzoli, C. Taking Care of Forced Migrants Together: Strengths and Weaknesses of Interorganizational Work from the Perspective of Social Workers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devilly, G.J.; Wright, R.; Varker, T. Vicarious Trauma, Secondary Traumatic Stress or Simply Burnout? Effect of Trauma Therapy on Mental Health Professionals. Aust. N. Zeal. J. Psychiatry 2009, 43, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliffe, G.; Steed, L.G. Exploring the Counselor’s Experience of Working with Perpetrators and Survivors of Domestic Violence. J. Interpers. Violence 2000, 15, 393–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bride, B.E.; Radey, M.; Figley, C.R. Measuring Compassion Fatigue. Clin. Soc. Work J. 2007, 35, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figley, C.R. Compassion Fatigue: Coping with Secondary Traumatic Stress Disorder in Those Who Treat the Traumatized; Taylor & Francis Ltd.: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- De Micco, V. Migrare. Sopravvivere al disumano. Riv. Ital. Psicoanal. 2017, 4, 667–669. [Google Scholar]

- Margherita, G.; Tessitore, F. From individual to social and relational dimensions in asylum-seekers’ narratives: A multi-dimensional approach. Eur. J. Psychother. Couns. 2019, 21, 96–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebren, G.; Demircioğlu, M.; Çırakoğlu, O.C. A neglected aspect of refugee relief works: Secondary and vicarious traumatic stress. J. Trauma. Stress 2022, 30, e6217–e6227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akkurt, Y.M. Secondary Traumatic Stress on Lawyers Who Are Working with Migrants. Ph.D. Thesis, Ted University, Ankara, Türkiye, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, M.A.; Dasgupta, A.; Taşğın, N.Ş.; Meinhart, M.; Tekin, U.; Yükseker, D.; Kaushal, N.; El-Bassel, N. Secondary Traumatic Stress, Depression, and Anxiety Symptoms Among Service Providers Working with Syrian Refugees in Istanbul, Turkey. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2022, 24, 1421–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemignani, M.; Giliberto, M. Constructions of burnout, identity, and self-care in professionals working toward the psychosocial care of refugees and asylum seekers in Italy. J. Constr. Psychol. 2021, 34, 56–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonnis, M.; Massidda, D.; Cabiddu, C.; Cuccu, S.; Pedditzi, M.L.; Cortese, C.G. Motivation to donate, job crafting, and organizational citizenship behavior in blood collection volunteers in non-profit organizations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guhan, R.; Liebling-Kalifani, H. The experiences of staff working with refugees and asylum seekers in the United Kingdom: A grounded theory exploration. J. Immigr. Refug. Stud. 2011, 9, 205–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieslak, R.; Shoji, K.; Douglas, A.; Melville, E.; Luszczynska, A.; Benight, C.C. A meta-analysis of the relationship be-tween job burnout and secondary traumatic stress among workers with indirect exposure to trauma. Psychol. Serv. 2014, 11, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamm, B.H. The Concise ProQOL Manual, 2nd ed.; ProQOL.org: Pocatello, ID, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sagaltici, E.; Cetinkaya, M.; Nielsen, S.Y.; Sahin, S.K.; Gulen, B.; Altindag, A. Identified predictors and levels of burnout among staff workers in a refugee camp of first immigrant group: A cross-sectional study. Medicine 2022, 11, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiling, A.; Böttche, M.; Knaevelsrud, C.; Stammel, N. A comparison of interpreters’ wellbeing and work-related char-acteristics in the care of refugees across different work settings. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, D.; Stamm, B.H. Professional quality of life and trauma therapists. In Trauma, Recovery, and Growth: Positive Psychological Perspectives on Posttraumatic Stress; Joseph, S., Lindley, A., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 275–296. [Google Scholar]

- Figley, C.R. Compassion Fatigue: An introduction; Green Cross Foundations’ Gift from Within: Belfast, Ireland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Măirean, C. Emotion regulation strategies, secondary traumatic stress, and compassion satisfaction in healthcare provid-ers. J. Psychol. 2016, 150, 961–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauvola, R.S.; Vega, D.M.; Lavigne, K.N. Compassion fatigue, secondary traumatic stress, and vicarious traumatization: A qualitative review and research agenda. Occup. Health Sci. 2019, 3, 297–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.J.; Shin, S. The relationship between secondary traumatic stress and burnout in critical care nurses: The mediating effect of resilience. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2023, 74, 103327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Baek, W.; Lim, A.; Lee, D.; Pang, Y.; Kim, O. Secondary traumatic stress and compassion satisfaction mediate the association between stress and burnout among Korean hospital nurses: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2021, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J. Secondary traumatic stress and burnout of North Korean refugees service providers. Psychiatry Investig. 2017, 14, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, J.; Polivka, B.; Smoot, E.A.; Owens, H. Compassion fatigue in pediatric nurses. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2015, 30, e11–e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinderer, K.A.; VonRueden, K.T.; Friedmann, E.; McQuillan, K.A.; Gilmore, R.; Kramer, B.; Murray, M. Burnout, compassion fatigue, compassion satisfaction, and secondary traumatic stress in trauma nurses. J. Trauma Nurs. 2015, 21, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodeke-Gregson, E.A.; Holttum, S.; Billings, J. Compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress in UK therapists who work with adult trauma clients. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2013, 4, 21869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, F.; Teague, B.; Lee, J.; Rushworth, I. The Prevalence of Burnout and Secondary Traumatic Stress in Professionals and Volunteers Working with Forcibly Displaced People: A Systematic Review and Two Meta-Analyses. J. Trauma. Stress 2021, 34, 773–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusk, M.; Terrazas, S. Secondary Trauma Among Caregivers Who Work with Mexican and Central American Refugees. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 2015, 37, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardeen, J.R.; Kumpula, M.J.; Orcutt, H.K. Emotion regulation difficulties as a prospective predictor of posttraumatic stress symptoms following a mass shooting. J. Anxiety Disord. 2013, 27, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonn-Miller, M.O.; Vujanovic, A.A.; Boden, M.T.; Gross, J.J. Posttraumatic stress, difficulties in emotion regulation, and coping-oriented marijuana use. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2011, 40, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujanovic, A.A.; Bonn-Miller, M.O.; Potter, C.M.; Marshall, E.C.; Zvolensky, M.J. An evaluation of the relation be-tween distress tolerance and posttraumatic stress within a trauma-exposed sample. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2011, 33, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schore, A.N. Relational trauma and the developing right brain: The neurobiology of broken attachment bonds. In Relational Trauma in Infancy: Psychoanalytic, Attachment and Neuropsychological Contributions to Parent–Infant Psychotherapy; Baradon, T., Ed.; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2009; pp. 19–47. [Google Scholar]

- Bromberg, P.M. Shrinking the tsunami: Affect regulation, dissociation, and the shadow of the flood. Contemp. Psychoanal. 2008, 44, 329–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopper, J.W.; Frewen, P.A.; Van der Kolk, B.A.; Lanius, R.A. Neural correlates of reexperiencing, avoidance, and dissociation in PTSD: Symptom dimensions and emotion dysregulation in responses to script-driven trauma imagery. J. Trauma. Stress 2007, 20, 713–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucci, C.; Scalabrini, A. Traumatic effects beyond diagnosis: The impact of dissociation on the mind–body–brain system. Psychoanal. Psychol. 2021, 38, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimmenti, A.; Caretti, V. Attachment, trauma, and alexithymia. In Alexithymia: Advances in Research, Theory, and Clinical Practice; Luminet, O., Bagby, R.M., Taylor, G.J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 127–141. [Google Scholar]

- Gratz, K.L.; Roemer, L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2004, 26, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloitre, M.; Miranda, R.; Stovall-McClough, K.C.; Han, H. Beyond PTSD: Emotion regulation and interpersonal problems as predictors of functional impairment in survivors of childhood abuse. Behav. Ther. 2005, 36, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Kolk, B.A.; Roth, S.; Pelcovitz, D.; Sunday, S.; Spinazzola, J. Disorders of extreme stress: The empirical foun-dation of a complex adaptation to trauma. J. Trauma. Stress 2005, 18, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boden, M.T.; Westermann, S.; McRae, K.; Kuo, J.; Alvarez, J.; Kulkarni, M.R.; Gross, J.J.; Bonn-Miller, M.O. Emotion regulation and posttraumatic stress disorder: A prospective investigation. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 32, 296–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprang, G.; Ford, J.; Kerig, P.; Bride, B. Defining secondary traumatic stress and developing targeted assessments and interventions: Lessons learned from research and leading experts. Traumatology 2019, 25, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benuto, L.T.; Yang, Y.; Bennett, N.; Lancaster, C. Distress tolerance and emotion regulation as potential mediators between secondary traumatic stress and maladaptive coping. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, 13–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bing, H.; Sadjadi, B.; Afzali, M.; Fathi, J. Self-efficacy and emotion regulation as predictors of teacher burnout among English as a foreign language teachers: A structural equation modeling approach. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 900417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamonti, P.; Conti, E.; Cavanagh, C.; Gerolimatos, L.; Gregg, J.; Goulet, C.; Pifer, M.; Edelstein, B. Coping, cognitive emotion regulation, and burnout in long-term care nursing staff: A preliminary study. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2019, 38, 92–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khouri, M.; Lassri, D.; Cohen, N. Job burnout among Israeli healthcare workers during the first months of COVID-19 pandemic: The role of emotion regulation strategies and psychological distress. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0265659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cote, S.; Morgan, L.M. A longitudinal analysis of the association between emotion regulation, job satisfaction, and intention to quit. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 2002, 23, 947–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, O.P.; Gross, J.J. Healthy and unhealthy emotion regulation: Personality processes, individual differences, and life span development. J. Personal. 2004, 72, 1301–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloitre, M.; Khan, C.; Mackintosh, M.A.; Garvert, D.W.; Henn-Haase, C.M.; Falvey, E.C.; Saito, J. Emotion regulation mediates the relationship between ACES and physical and mental health. Psychol. Trauma: Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2019, 11, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopfinger, L.; Berking, M.; Bockting, C.L.; Ebert, D.D. Emotion regulation mediates the effect of childhood trauma on depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 198, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, R.E.; Chesney, S.A.; Heath, N.M.; Barlow, M.R. Emotion regulation difficulties mediate associations between betrayal trauma and symptoms of posttraumatic stress, depression, and anxiety. J. Trauma. Stress 2013, 26, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kira, I.A.; Shuwiekh, H.; Al Ibraheem, B.; Aljakoub, J. Appraisals and emotion regulation mediate the effects of identity salience and cumulative stressors and traumas, on PTG and mental health: The case of Syrian’s IDPs and refugees. Self Identity 2019, 18, 284–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, S. Mindfulness Sessions for The Prevention of Compassion Fatigue in Pediatric Oncology Nurses. Master’s Thesis, Arkansas Tech University, Russellville, AR, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Palestini, L.; Prati, G.; Pietrantoni, L.; Cicognani, E. La qualità della vita professionale nel lavoro di soccorso: Un con-tributo alla validazione italiana della Professional Quality of Life Scale (ProQOL). Psicoter. Cogn. E Comport. 2009, 15, 205–227. [Google Scholar]

- Bride, B.E.; Robinson, M.M.; Yegidis, B.; Figley, C.R. Development and validation of the secondary traumatic stress scale. Res. Soc. Work. Pract. 2009, 14, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setti, I.; Argentero, P. Vicarious Trauma: A Contribution to the Italian Adaptation of the Secondary Traumatic Stress Scale in a Sample of Ambulance Operators; Giunti Organizzazioni Speciali: Milan, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sighinolfi, C.; Norcini Pala, A.; Chiri, L.R.; Marchetti, I.; Sica, C. Difficulties in emotion regulation scale (DERS): The Italian translation and adaptation. Psicoter. Cogn. Comport. 2010, 16, 141–170. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, S.K.K.; Lønfeldt, N.; Wolitzky-Taylor, K.B.; Hageman, I.; Vangkilde, S.; Daniel, S.I.F. Adult attachment style and anxiety–The mediating role of emotion regulation. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 218, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickard, J.A.; Caputi, P.; Grenyer, B.F. Mindfulness and emotion regulation as sequential mediators in the relationship between attachment security and depression. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2016, 99, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, A.A.; Panzieri, A.; Marrini, S. The Italian Version of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale—Short Form (IT-DERS-SF): A Two Step Validation Study. J. Psychopatology Behav. Assess. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyle, R.H. Handbook of Strucural Equation Modeling; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.A. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research, 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- van de Schoot, R.; Lugtig, P.; Hox, J. A checklist for testing measurement invariance. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2012, 9, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, C.; Singer, J.; Hisaka, R.; Benuto, L.T. Compassion satisfaction to combat work-related burnout, vicarious trauma, and secondary traumatic stress. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, NP5304–NP5319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.J.; Lee, M.; Jang, S.J. Compassion satisfaction, secondary traumatic stress, and burnout among nurses working in trauma centers: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Y.; Zhang, C.; Han, X.R.; Li, W.; Wang, Y.L. Determinants of compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue and burn out in nursing: A correlative meta-analysis. Medicine 2018, 97, e11086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akinsulure-Smith, A.M.; Espinosa, A.; Chu, T.; Hallock, R. Secondary Traumatic Stress and Burnout Among Refugee Resettlement Workers: The Role of Coping and Emotional Intelligence. J. Trauma. Stress 2018, 31, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, S.M.I.H.; Yaqoob, N.; Saeed, H. Compassion satisfaction, secondary traumatic stress and burnout among rescuers. J. Postgrad. Med. Inst. 2017, 31, 314–318. [Google Scholar]

- Gozzoli, C.; Leo, A.D. Receiving asylum seekers: Risks and resources of professionals. Health Psychol. Open 2020, 7, 2055102920920312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessitore, F.; Parola, A.; Margherita, G. Mental health risk and protective factors of Nigerian male asylum seekers hosted in southern Italy: A culturally sensitive quantitative investigation. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2022, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohleber, W. Ricordo, trauma e memoria collettiva: La battaglia per il ricordo in psicoanalisi. Riv. Psicoanal. 2007, 53, 367–394. [Google Scholar]

- Margherita, G.; Troisi, G.; Incitti, M.I. “Dreaming Undreamt Dreams” in Psychological Counseling with Italian Women Who Experienced Intimate Partner Violence: A Phenomenological-Interpretative Analysis of the Psychologists’ Experience. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzolino, M.; Celia, G.; Girelli, L.; Limone, P. Effects of the brain wave modulation technique administered online on stress, anxiety, global distress, and affect during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic: A randomized clinical trial. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 635877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participants (n = 264) | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 63 (23.9) |

| Female | 201 (76.1) |

| Mean age (SD) | 39.39 (9.59) |

| Type of employment | |

| Employed | 231 (87.5) |

| Self-employed | 33 (12.5) |

| Professional role | |

| Legal workers | 25 (9.5) |

| Caseworkers | 32 (12.1) |

| Coordinators | 26 (9.8) |

| Cultural mediators | 29 (11.0) |

| Educators | 43 (16.3) |

| Health workers (i.e., psychologists, doctors) | 28 (10.6) |

| Social workers | 81 (30.7) |

| α | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Compassion Satisfaction | 0.877 | 39.15 | 0.56 | - | |||||

| 2 | Burnout | 0.663 | 22.28 | 4.76 | −0.584 * | - | ||||

| 3 | Emotional regulation | 0.942 | 61.53 | 19.65 | −0.356 * | 0.612 * | - | |||

| 4 | Arousal | 0.884 | 19.76 | 6.54 | −0.280 * | 0.642 * | 0.693 * | - | ||

| 5 | Intrusion | 0.771 | 10.79 | 3.62 | −0.077 | 0.464 * | 0.569 * | 0.677 * | - | |

| 6 | STSS | 0.903 | 30.55 | 9.38 | −0.225 * | 0.627 * | 0.703 * | 0.959 * | 0.858 * | - |

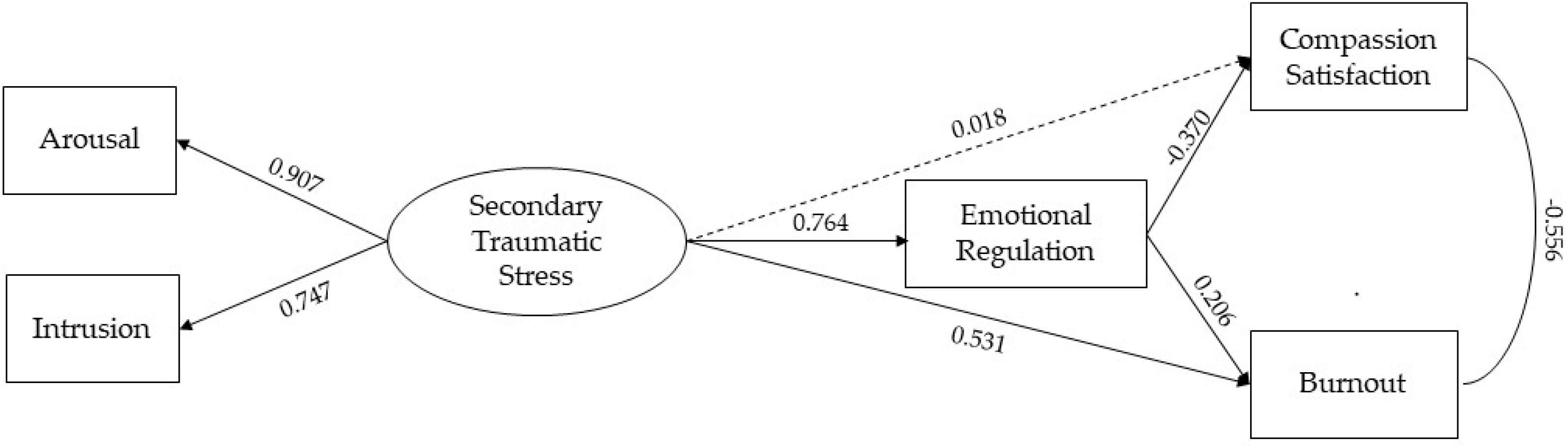

| β | SE | 95% CI [L–U] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| STSS → ER | 0.764 | 0.045 | [0.665, 0.839] |

| STSS → CS | 0.018 | 0.126 | [−0.231, 0.264] |

| STSS → BO | 0.531 | 0.090 | [0.369, 0.719] |

| ER → CS | −0.370 | 0.112 | [−0.590, −0.148 |

| ER → BO | 0.206 | 0.092 | [0.012, 0.373] |

| Indirect effect of STSS to CS via ER | −0.282 | 0.080 | [−0.470, −0.111] |

| Indirect effect of STSS to BO via ER | 0.158 | 0.068 | [0.009, 0.284] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tessitore, F.; Caffieri, A.; Parola, A.; Cozzolino, M.; Margherita, G. The Role of Emotion Regulation as a Potential Mediator between Secondary Traumatic Stress, Burnout, and Compassion Satisfaction in Professionals Working in the Forced Migration Field. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2266. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032266

Tessitore F, Caffieri A, Parola A, Cozzolino M, Margherita G. The Role of Emotion Regulation as a Potential Mediator between Secondary Traumatic Stress, Burnout, and Compassion Satisfaction in Professionals Working in the Forced Migration Field. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(3):2266. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032266

Chicago/Turabian StyleTessitore, Francesca, Alessia Caffieri, Anna Parola, Mauro Cozzolino, and Giorgia Margherita. 2023. "The Role of Emotion Regulation as a Potential Mediator between Secondary Traumatic Stress, Burnout, and Compassion Satisfaction in Professionals Working in the Forced Migration Field" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 3: 2266. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032266

APA StyleTessitore, F., Caffieri, A., Parola, A., Cozzolino, M., & Margherita, G. (2023). The Role of Emotion Regulation as a Potential Mediator between Secondary Traumatic Stress, Burnout, and Compassion Satisfaction in Professionals Working in the Forced Migration Field. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), 2266. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032266