Taking Care of Forced Migrants Together: Strengths and Weaknesses of Interorganizational Work from the Perspective of Social Workers

Abstract

1. Introduction

- -

- Weaknesses of the network of services;

- -

- Strengths of the network of services;

- -

- Areas for improvement of the network.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Aims and Scopes

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measures

2.4. Methods and Procedure

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

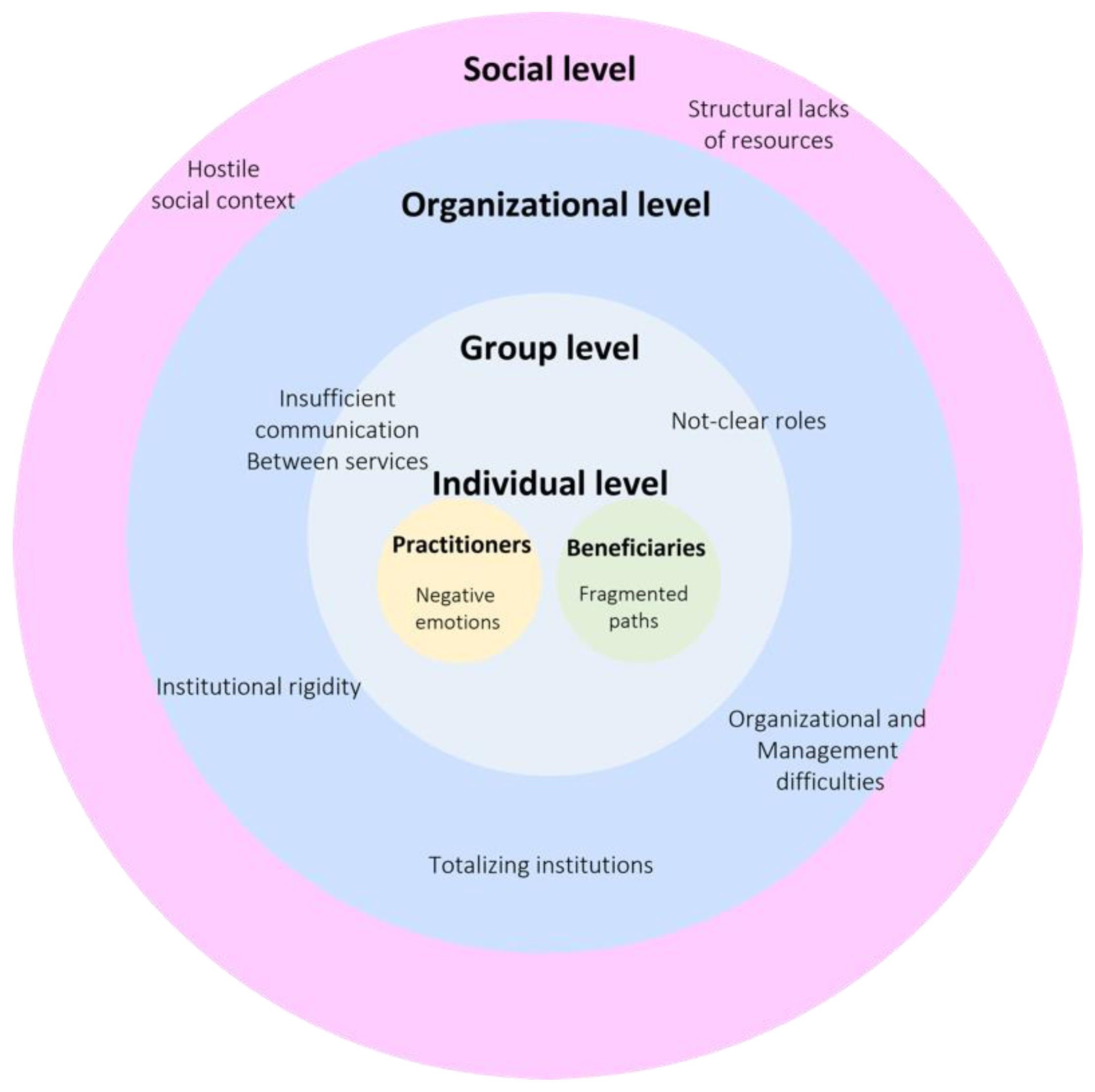

3.1. Weaknesses of the Network of Services

3.1.1. Hostile Social Context

“In the last few years, due to changes in politics, I realized how much hostility there is towards reception services and towards specific professional categories. As a professional who’s working in this area, I perceived a greater hostility from the citizens. I believe that this is one of the consequences of the economic crisis, and it is also due to political events which spread a different reception culture.”(Operator in Health and Psychological Wellness Area)

“…with the Security Decree in 2018, which became law, the fundamental institution of humanitarian protection came to a standstill.”(Operator in Legal Area)

“In my opinion, a constant problem is the difficulty of approaching all irregular migrants who have not been accepted into dedicated facilities because they do not have the requirements for or any kind of international protection.”(Operator in Health and Psychological Wellness Area)

3.1.2. Structural Lack of Resources

“From my point of view, there is still a great hole in traditional psychiatry institutions. Bringing new cases to a structure already saturated, it seems to me that the attention and desire of the most valid and available doctor are linked to the resources that are in the structure itself.”(Operator in Reception Area)

“There are particular situations that require specific tools to be solved, which we do not currently have.”(Operator in Legal Area)

“Because most of the migrants do not have a family, they look for social structures; the social contribution is typically asked to the third sector and not to local government. The inclination to delegate to the private sector is more and more present, and we put all our strength into play, but it is necessary a structural reform by the region of Lombardy and the Ministry of Health to overcome these structural fragilities in the public sector.”(Operator in Reception Area)

3.1.3. Negative Emotions

“It is everyone’s problem: operators, institutions and migrants. Because that rage, that aggressiveness and that discouragement feeling could affect the operators’ integrity and the institutions themselves. This is the biggest fear that lingers and belongs to our project.”(Operator in Reception Area)

3.1.4. Organizational and Management Difficulties

“As far as we are concerned, we wedge interventions in an overloaded schedule that provides for something else. We are aware that this is a limit, considering that each intervention requires the networking of several actors: the beneficiary, us and the mediator. We perceive a bit of stress in doing these things; on the other hand, we need more time and a less rigorous agenda.”(Operator in Health and Psychological Wellness Area)

“Networking has always been difficult and is unfortunately promoted very little. It is easier not to do because it takes a lot of time and effort to deal with. Moreover, teamwork requires collaboration with people with whom we may have almost nothing in common.”(Operator in Reception Area)

3.1.5. Institutional Rigidity

“I noticed this kind of closure on the part of some institution. There was a tendency to use one’s own standard, one’s own model of thinking. An ethnological approach with more understanding of the person’s story is surely more difficult. It requires time and could be not in all operators’ expertise, although it would be in everyone’s best intentions.”(Operator in Family Area)

“Having poor training is a weakness, for sure. Also, the lack of an intercultural aptitude is a gap.”(Operator in Legal Area)

“I have to say that there is an inadequate formation and general disorientation on the theme. In my opinion, the asylum seekers have always been managed as a separate universe.”(Operator in Family Area)

3.1.6. Insufficient Communication between Services and Not-Clear-Roles

“First of all, we lack the right tools. We are service, a reality among a lot of services in the Brescia area. We should define the roles first. There is a lack of coordination and communication between horizontal networks, which should coordinate better to be able to manage cases properly and find the right solution.”(Operator in Legal Area)

“Many services consider little the legal area. […] very often when I deal with social workers, and they pass me a case, they don’t even know which residence permit people have if they have one.”(Operator in Legal Area)

3.1.7. Fragmented Post-Migratory Paths

“One limitation, something that I always felt was very important, is the fact that there are so many actors within the network. The beneficiaries, then, are forced to repeat many times something that is always new to us. Listening to their story is obviously necessary to be able to do our work, but for them, it is the telling of something that I feel is very violent [for them] every time.”(Operator in Health and Psychological Wellness Area)

“Feelings of anger are present. I am convinced that we are working in a place of conflict;: we are aware that the reception process will never be linear and easy. It has consequences for us, the beneficiaries, on the territory where the conflict takes place. If we cannot manage this kind of conflict, we will never be able to understand how to elaborate positively. In addition to the conflict, we are harboring drastic feelings, such as anger. These days I am taking care of certain people with huge anger towards us, but they should address this feeling towards institutions that are responsible for this anger.”(Operator in Reception Area)

3.1.8. Totalizing Institutions

“There is no space for these young people to reveal a situation of discomfort in a SPRAR (the system of reception and integration promoted by the Ministry of the Interior and the local authorities) project. The vulnerable kids we deal with need their time for some situations to emerge. History tells us that some steps are fundamental; indeed, the most serious situations emerged after a period of tranquility when their emotions and efforts have had a safe context to be told.”(Operator in Reception Area)

“Most of them live in these structures as a place of transit, where they wait for specific answers (i.e., their documents). When these answers come, they will make their own decisions without investing a lot.”(Operator in Reception Area)

“The SPRAR project was thought of as a long-term project, and it should offer specific tools to address people’s autonomy. In that way, migrants should be able to assimilate into the host society at work and socioeconomic levels. Indeed, after a SPRAR project dedicated to mental needs, there should be something else that is not there.”(Operator in Legal Area)

3.2. Strengths of the Network of Services

3.2.1. Mental Health Care

“In my opinion, it is not that clients are changed. What has really changed is how we accept their psychic suffering in the different areas of response.”(Operator in Health and Psychological Wellness Area)

“Recently, we have been working in teams in a more qualitative way. Lately, we are hosting fewer people, but the care for them is 360°. We are trying to address the person’s suffering from multiple perspectives. In fact, there are educators and professionals who activate individual pathways for inclusion, such as alphabetization, both for migrants inside and outside of refugee centers.”(Operator in Health and Psychological Wellness Area)

3.2.2. Professionals’ Interpersonal Relationships

“As a service, being in touch with these realities is fundamental. It exists from our point of view, which is [that of the] legal operators’. We are in contact with the structures that deal with mental health, and it is useful to understand the work practices that we are supporting. Then the exchange of view could be both unidirectional and bidirectional.”(Operator in Legal Area)

“What has changed in the approach is the necessity to collaborate and intertwine more professionalism to face bureaucratic problems. Indeed, a single CPS (mental health center) social worker, a single outpatient doctor or even just a single institution alone could not manage face up to.”(Operator in Health and Psychological Wellness Area)

“Collaborating with the START project has made it possible to have alternative points of view, different interpretations and having home care support both for these situations and interviews, which are conducted by the psychologist in charge. This collaboration has allowed us to work in synergy and, in my opinion, respond fair enough to the needs of families. These are families that come here anyway and have no support other than that of Reception centers. They do not have a great possibility to ask people for help except for a few friends and relatives.”(Operator in Family Area)

3.2.3. Relationship with Beneficiaries

“We specialized in working with these families. I have to say that working with asylum seekers is very satisfying […] Although there are difficulties in working with families, the fact that there are minors gives the idea that there is also a sort of future, a hope for the future for these people. Also, for the operators, it is not a bad thing because it gives us the energy and strength to continue. It is also nice to see children being born; indeed, it is very nice.”(Operator in Family Area)

3.2.4. Acknowledgment and Trust among Services

“I have to say that I have never felt mistrust from other professionals for the work we do at the legal support office, in the sense that in any case, we have tried to help beneficiaries to get residence permits despite legislative changes […]. So, I must say that the attitude of people has actually been very helpful; I have always found people who were very trusting of the legal accompaniment that we have tried to provide even in this transitional period.”(Operator in Legal Area)

3.3. Possibility of Improvement in the Quality of the Network

3.3.1. Need to Formalize the Network

“If you do an interview with a beneficiary, you have to consider at least two or three networks because working with migrants always requires connection and synergy with colleagues. So, services need to formalize this requirement and have moments of coordination; it would help us a lot.”(Operator in Health and Psychological Wellness Area)

“…periodic meetings are defined with the main subjects we interface with: police headquarters, prefecture, and commission. It does not mean that we must see each other every month, it could also be twice a year, but it must be a place where all the problems and the possible solutions are put on the table. They should not fall on deaf ears! So, we should meet again and see how it goes on and what progress has been made. In this sense, it would be interesting if psychiatry institutions will take part in this meeting because mental illness is an ever-growing element, and we already talk about this at our ‘Periferie della cura’ (Peripheries of care) meeting (“Peripheries of care” is an interinstitutional board involving different local actors (Province and Municipality of Brescia, Provincial Coordination of Italian Reception System projects, Spedali Civili Brescia hospital) that deal with the reception and care of forced migrants. The main objective of the board is to investigate and compare practices and theories of care of the forced migrant)”(Operator in Legal Area)

“In my opinion, it is very interesting to think about networking among the different realities that deal with forced migrants, especially in a municipality like Brescia that also has SPRAR. The municipality of Brescia manages different sectors: the SPRAR is the inclusion sector, while the social services sector that deals with the territory are precisely another sector, so let’s say that there is not a constant flow of communication constant between the two sectors and instead, it would be very important that there is”(Operator in Family Area)

3.3.2. Development of New Tools

“Keeping the presence of a constant mediator and not changing him: […] often the mediator is the person who already knows the patient’s story. The mediator helps the person to ‘re-narrate’ his or her story, to remember certain very intense themes of great suffering.”(Operator in Health and Psychological Wellness Area)

“The narration, the re-narration and the ulterior narration of my life, of my discomfort, of my story, of my multifigure needs, goes in parallel with the operator’s need that the migrant narrates, re-narrates, re-tells to each institution what has happened and what’s happening. So, I don’t know if it is practicable or possible, but I think that it would be innovative if these people were given either a case manager or a single folder that collects all the documentation. In this way, whoever intervenes would be updated at any time, and the migrant would be less scared of not re-living everything emotionally again.”(Operator in Health and Psychological Wellness Area)

“So, the need to find new procedures, which had not been thought of before because there was no need for them to exist, leads us to somehow be more creative and find original methods. These methods should be recognized and approved by those who coordinate the institutions.”(Operator in Health and Psychological Wellness Area)

3.3.3. Need to Train and Inform

“So, from my point of view, we really should open a school, a university space, we’re thinking about these topics finds its institutional place where being inserted. Being able to build a thought that is periodically confronted with all mental approaches would lead to the determination of consequent practices. […] we must also consider the cultural approach.”(Operator in Reception Area)

“There is the idea of setting up an ethnoclinical center, which first and foremost is concerned with training those who work in the public and also those who work in the so-called private sector. […] I would like to think that we can build such a pathway […] a center where we can train and share procedures, projects, practices, and above all help set up to shared thinking.”(Operator in Reception Area)

“Everyone’s role […] is also to spread competence, and likewise, the role of the local social service should be to get information and be involved. […] the goal must be to create a competent community in this field so that they also are on the territory.”(Operator in Family Area)

3.3.4. Promote a Culture of Hospitality

“We need to find a system to make ourselves promoters, not so much in a specific and specialized, or super-specialized, environment, where we only go to refine things. But we should create a basic resonance that, in the long run, could also generate and that could also be proactive for the single user. We need to become promoters of a territorial culture a little more detailed, concrete and informed about what we do and what our beneficiaries require.”(Operator in Health and Psychological Wellness Area)

“I think being able to work on these themes as well makes the SPRAR project interventions in schools very valuable. When students from middle and high school hear the stories and testimonies experience a little bit firsthand what we are talking about, even before they go to college. That is, this human reality that is not so far away and not so strange.”(Operator in Health and Psychological Wellness Area)

“…because the more information is disseminated, the more effective the service is also for social network and integration of migrants.”(Operator in Legal Area)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Qayyum, M.A.; Thompson, K.M.; Kennan, M.A.; Lloyd-Zantiotis, A. The provision and sharing of information between service providers and settling refugees. Inf. Res. 2014, 19, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Dossetti, G. Scritti Politici: 1943–1951; Marietti: Rome, Italy, 1995; Volume 65. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, B.; Nowak, J. The New Localism: How Cities Can Thrive in the Age of Populism; Brookings Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Campomori, F.; Ambrosini, M. Multilevel governance in trouble: The implementation of asylum seekers’ reception in Italy as a battleground. Comp. Migr. Stud. 2020, 8, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, P. Pathologies of Power: Health, Human Rights, and the New War on the Poor; Univ of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2004; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Giovannetti, M. Politiche e pratiche di accoglienza dei minori stranieri non accompagnati in Italia. E-Migrinter 2008, 2, 98–120. [Google Scholar]

- Ambrosini, M. ‘We are against a multi-ethnic society’: Policies of exclusion at the urban level in Italy. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2013, 36, 136–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholten, P.W. Agenda dynamics and the multi-level governance of intractable policy controversies: The case of migrant integration policies in the Netherlands. Policy Sci. 2013, 46, 217–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholten, P.; Penninx, R. The multilevel governance of migration and integration. In Integration Processes and Policies in Europe; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 91–108. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, S. Multi-level governance of an intractable policy problem: Migrants with irregular status in Europe. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2018, 44, 2034–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, C.; Dekker, R.; Geuijen, K.; Broadhead, J. Innovative strategies for the reception of asylum seekers and refugees in European cities: Multi-level governance, multi-sector urban networks and local engagement. Comp. Migr. Stud. 2020, 8, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferlie, E.; Montgomery, K.; Pedersen, A.R. (Eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Health Care Management; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hoberecht, S.; Joseph, B.; Spencer, J.; Southern, N. Inter-organizational networks. OD Sustain. 2011, 43, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Popp, J.; MacKean, G.L.; Casebeer, A.; Milward, H.B.; Lindstrom, R.R. Inter-Organizational Networks: A Review of the Literature to Inform Practice; IBM Center for the Business of Government: Washington, DC, USA, 2014.

- Castles, S. Towards a sociology of forced migration and social transformation. Sociology 2003, 37, 13–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leo, A.; Cotrufo, P.; Gozzoli, C. The Refugee Experience of Asylum Seekers in Italy: A Qualitative Study on the Intertwining of Protective and Risk Factors. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2022, 24, 1224–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhugra, D.; Jones, P. Migration and mental illness. Adv. Psychiatr. Treat. 2001, 7, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessitore, F.; Gallo, M.; Cozzolino, M.; Margherita, G. The frame of Nigerian sex trafficking between internal and external usurpers: A qualitative research through the gaze of the female Nigerian cultural mediators. Int. J. Appl. Psychoanal. Stud. 2022, 19, 499–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, D.; Dooley, B.; Benson, C. Theoretical perspectives on post-migration adaptation and psychological well-being among refugees: Towards a resource-based model. J. Refug. Stud. 2008, 21, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, M. “Pensavo di Essere Libero e Invece no” Debiti, Violenze, Sfruttamento dei Trafficanti Nelle Memorie Autografe dei Rifugiati; Tau Editrice e Fondazione Migrantes della CEI: Todi, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hodes, M.; Vasquez, M.M.; Anagnostopoulos, D.; Triantafyllou, K.; Abdelhady, D.; Weiss, K.; Skokauskas, N. Refugees in Europe: National overviews from key countries with a special focus on child and adolescent mental health. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2018, 27, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yates, L. Interaction, language learning and social inclusion in early settlement. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 2011, 14, 457–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brücker, H.; Kosyakova, Y.; Vallizadeh, E. Has there been a “refugee crisis”? New insights on the recent refugee arrivals in Germany and their integration prospects. SozW Soz. Welt 2020, 71, 24–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhugra, D. Migration and mental health. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2004, 109, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlaudt, V.A.; Bosson, R.; Williams, M.T.; German, B.; Hooper, L.M.; Frazier, V.; Ramirez, J. Traumatic experiences and mental health risk for refugees. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Napoli, A.; Rossi, A.; Baralla, F.; Ventura, M.; Gatta, R.; Perez, M.; Petrelli, A. Self-perceived workplace discrimination and mental health among immigrant workers in Italy: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockemer, D.; Niemann, A.; Unger, D.; Speyer, J. The “Refugee Crisis,” Immigration Attitudes, and Euroscepticism. Int. Migr. Rev. 2020, 54, 883–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, L.A.; Guild, E. Seeking refuge in Europe: Spaces of transit and the violence of migration management. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2019, 45, 2156–2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, A. The mental-health crisis among migrants. Nature 2016, 538, 158–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akik, C.; Ghattas, H.; Mesmar, S.; Rabkin, M.; El-Sadr, W.M.; Fouad, F.M. Host country responses to non-communicable diseases amongst Syrian refugees: A review. Confl. Health 2019, 13, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tortelli, A.; Perquier, F.; Melchior, M.; Lair, F.; Encatassamy, F.; Masson, C.; Mercuel, A. Mental Health and Service Use of Migrants in Contact with the Public Psychiatry System in Paris. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouriou, F. Psychopathologie et Migration: Repérage Historique et Épistémologique dans le Contexte Français. Ph.D. Dissertation, Université Rennes 2, Rennes, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jolivet, A.; Cadot, E.; Florence, S.; Lesieur, S.; Lebas, J.; Chauvin, P. Migrant health in French Guiana: Are undocumented immigrants more vulnerable? BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchetti, C. Rifugiati e migranti forzati in Itália: Il pendolo tra‘emergenza‘e’sistema’. REMHU Rev. Interdiscip. Mobilidade Hum. 2014, 22, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, S.F. Forced Migration and Professionalism 1. Int. Migr. Rev. 2001, 35, 226–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozzoli, C.; Regalia, C. Migrazioni e Famiglie: Percorsi, Legami e Interventi Psicosociali; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gozzoli, C.; De Leo, A. Receiving asylum seekers: Risks and resources of professionals. Health Psychol. Open 2020, 7, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, L.; Morse, J.M. Readme First for a User’s Guide to Qualitative Methods; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Colombo, M. Una Società Smarrita: Rischio Pandemico, Solidarietà Locale e Sfida alle Scienze Socialiintroduzione al CIRMiB MigraREport 2020; Vita e Pensiero: Milan Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Finch, H.; Lewis, J.; Turley, C. Focus groups. Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers. Nurse Res. 2003, 2, 211–242. [Google Scholar]

- Kaissi, A. Manager-physician relationships: An organizational theory perspective. Health Care Manag. 2005, 24, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, D.L.; Krueger, R.A.; Scannell, A.U. Planning Focus Groups; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ahern, N.R. Using the Internet to conduct research. Nurse Res. 2005, 13, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Woodyatt, C.R.; Finneran, C.A.; Stephenson, R. In-person versus online focus group discussions: A comparative analysis of data quality. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, J.A. Reflecting on the development of interpretative phenomenological analysis and its contribution to qualitative research in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2004, 1, 39–54. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.A.; Osborn, M. Interpretative phenomenological analysis as a useful methodology for research on the lived experience of pain. Br. J. Pain 2015, 9, 41–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eatough, V.; Smith, J.A. Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 193–209. [Google Scholar]

- Brocki, J.M.; Wearden, A.J. A critical evaluation of the use of interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) in health psychology. Psychol. Health 2006, 21, 87–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.A. Evaluating the contribution of interpretative phenomenological analysis. Health Psychol. Rev. 2011, 5, 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.A.; Jarman, M.; Osborn, M. Doing interpretative phenomenological analysis. Qual. Health Psychol. Theor. Methods 1999, 1, 218–240. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.A.; Osborn, M. Chapter 4: Interpretative phenomenological analysis. Qualitative Psychology: A Practical Guide to Research Methods, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Corvino, C.; D’Angelo, C.; De Leo, A.; Martín, R.S. How Can Performing Arts and Urban Sport Enhance Social Inclusion and Interculturalism in the Public Space? An Explorative Ethnography of Migrants’ Performances in the City of Milan, Italy. Commun. Soc. 2019, 41, 148–165. [Google Scholar]

- Gozzoli, C.; Gazzaroli, D. When Are Organizations Sustainable? Well-Being and Discomfort in Working Contexts: Old and New Form of Malaise. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carswell, K.; Blackburn, P.; Barker, C. The relationship between trauma, post-migration problems and the psychological well-being of refugees and asylum seekers. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2011, 57, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessitore, F. The Asylum Seekers Photographic Interview (ASPI): Evaluation of a new method to increase Nigerian asylum seekers’ narrative meaning-making after trauma. Psychol. Trauma: Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2022, 14, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tessitore, F.; Parola, A.; Margherita, G. Mental health risk and protective factors of Nigerian male asylum seekers hosted in southern Italy: A culturally sensitive quantitative investigation. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2022, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corvino, C.; Gazzaroli, D.; D’Angelo, C. Dialogic evaluation and inter-organizational learning: Insights from two multi-stakeholder initiatives in sport for development and peace. Learn. Organ. 2022, 29, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozzoli, C.; D’Angelo, C.; Tamanza, G. Training and resistance to change: Work with a group of prison guards. World Futur. 2018, 74, 426–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Areas | Types of Organizations | Tasks |

|---|---|---|

| Health & psychological well-being area | Hospital (psychiatric department), associations, territorial services | Health mental care |

| Reception area | Reception centers | Housing, language courses, financial support for food, medical care support for integration, job orientation |

| Family area | Social cooperative, municipality | Support to families and minors |

| Legal area | Municipal legal office | Legal assistance |

| Participants | Sex | Age | Professional Role | Services Area |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 53 | Coordinator | Family area |

| 2 | M | 47 | Coordinator | Family area |

| 3 | F | 34 | Social workers | Family area |

| 4 | M | 37 | Psychologist | Family area |

| 5 | F | 29 | Practitioners | Family area |

| 6 | M | 48 | Psychotherapist | Health & psychological well-being area |

| 7 | M | 55 | Psychotherapist | Health & psychological well-being area |

| 8 | M | 43 | Psychotherapist | Health & psychological well-being area |

| 9 | F | 39 | Psychotherapist | Health & psychological well-being area |

| 10 | M | 59 | Psychiatrists | Health & psychological well-being area |

| 11 | M | 65 | Psychiatrists | Health & psychological well-being area |

| 12 | F | 35 | Social workers | Health & psychological well-being area |

| 13 | F | 28 | Cultural mediators | Health & psychological well-being area |

| 14 | F | 29 | Legal practitioners | Legal area |

| 15 | F | 34 | Legal practitioners | Legal area |

| 16 | F | 33 | Legal practitioners | Legal area |

| 17 | M | 42 | Legal practitioners | Legal area |

| 18 | F | 45 | Cultural mediators | Legal area |

| 19 | F | 38 | Cultural mediators | Reception area |

| 20 | M | 56 | Coordinator | Reception area |

| 21 | M | 49 | Coordinator | Reception area |

| 22 | M | 43 | Cultural mediators | Reception area |

| 23 | F | 35 | Practitioners | Reception area |

| 24 | F | 37 | Practitioners | Reception area |

| Superordinate Themes | Subordinate Themes | Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Weaknesses of the network of services | 1. Hostile social context | “I perceived, as a professional who’s working in this area, a greater hostility from the citizen.” |

| 2. Structural lack of resources | “From my point of view, there is still a great hole in traditional psychiatry institutions.” | |

| 3. Negative emotions | “That aggressiveness and that discouragement feeling could affect the operators’ integrity and institutions’ themselves.” | |

| 4. Organizational and management difficulties | “What we perceive is a bit of stress in doing these things; on the other hand, we need more time and a less rigorous agenda.” | |

| 5. Institutional rigidity | “I noticed this kind of closure on the part of some institutions. There was a tendency to use one’s own standard, one’s own model of thinking.” | |

| 6. Insufficient communication between services and not-clear-roles | “There is a lack of coordination and communication between horizontal networks, which should coordinate better to be able to manage cases properly and find the right solution.” | |

| 7. Fragmented post-migratory paths | “We are aware that the reception process will never be linear and easy [..] the beneficiaries, then, are forced to repeat many times their story.” | |

| 8. Totalizing institutions | “Most of them live in these facilities as a place of transit, where they wait for specific answers (i.e., their documents) without investing a lot.” | |

| Strengths of the network of services | 1. Mental health care | “What has really changed is how we accept and trait their psychic suffering in the different areas of response.” |

| 2. Professionals’ interpersonal relationships | “As a service, being in touch with these realities is fundamental. We are in contact with the structures that deal with mental health, and it is useful to understand the work practices that we are supporting. Then the exchange of view could be both unidirectional and bidirectional.” | |

| 3. Relationship with beneficiaries | “I have to say that working with asylum-seekers is very satisfying.” | |

| 4. Acknowledgment and trust among services | “I have to say that I have never felt mistrust from other professionals for the work we do at the legal support office.” | |

| Possibility of improving the quality of the network | 1. Need to formalize the network | “If you do an interview with a beneficiary, you must consider at least two or three networks because working with migrants always requires connection and synergy with colleagues. So, there is a need for services to formalize this requirement and have moments of coordination; it would help us a lot.” |

| 2. Development of new tools | “I don’t know if it is practicable or possible, but I think that it would be innovative if these people were given either a case manager or a single folder that collects all the documentation.” | |

| 3. Need to train and inform | “Everyone’s role […] is also to spread competence, and likewise, the role of the local social service should be to get information and be involved. […] the goal must be to create a competent community in this field so that they also are on the territory.” | |

| 4. Promote a culture of hospitality | “We need to find a system to make ourselves promoters, not so much in a specific and specialized, or super-specialized, environment, where we only go to refine things. But we should create a basic resonance that, in the long run, could also generate and that could also be proactive for the single user. Become promoters of a territorial culture a little more detailed, concrete and informed about what we do and what our beneficiaries require.” |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

De Leo, A.; D’Adamo, G.; Morozzi, C.; Gozzoli, C. Taking Care of Forced Migrants Together: Strengths and Weaknesses of Interorganizational Work from the Perspective of Social Workers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1371. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021371

De Leo A, D’Adamo G, Morozzi C, Gozzoli C. Taking Care of Forced Migrants Together: Strengths and Weaknesses of Interorganizational Work from the Perspective of Social Workers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(2):1371. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021371

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe Leo, Amalia, Giulia D’Adamo, Carlotta Morozzi, and Caterina Gozzoli. 2023. "Taking Care of Forced Migrants Together: Strengths and Weaknesses of Interorganizational Work from the Perspective of Social Workers" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 2: 1371. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021371

APA StyleDe Leo, A., D’Adamo, G., Morozzi, C., & Gozzoli, C. (2023). Taking Care of Forced Migrants Together: Strengths and Weaknesses of Interorganizational Work from the Perspective of Social Workers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 1371. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021371