Risk Factors for the Mental Health of Adolescents from the Parental Perspective: Photo-Voice in Rural Communities of Ecuador

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Risk Factors in Adolescents from Rural Communities of Ecuador

3.1.1. Personal Risk Factors

“Here they did not experience so much stress, since they have to go to the city they have more”.(S5-FG3)

“They stress because they are given lots of homework and they need to do the homework on time. If they don’t have help then they get stressed and feel sad because they think they can’t do something or that they don’t have the capacity to do it”.(S6-FG3)

“They are tired because I have also gone with my children, they get up at four in the morning to have breakfast and if we go past five minutes it is already late. They come home at four in the afternoon, they come tired, wanting to sleep for a whole day, right after one asks them to come help out with something in the house and they no longer want to, they arrive, eat at that time, do homework and they stay up late, they don’t rest well”.(S1-FG1)

“My daughter is going to study in the city, she has to get up early at 4 in the morning because at five she is already leaving”.(S8-FG4)

“You can see their behavior because sometimes their mood changes”.(S4-FG4)

“But on the other hand, if ever when the son feels bad or something happens one realizes, it is for the reason that we say he is quiet, calm or sad, we ask them, why do you feel sad, what is wrong with you or what do you need”.(S6-FG4)

“And of course they are active and suddenly if they go elsewhere they isolate themselves. Then one already realizes it”.(S2-FG5)

“If they have problems at school, they can’t give us good grades at the beginning of the school year or the end, so they get sad, depressed”.(S3-FG4)

“We (mothers) know when our children are sad”.(S5-FG5)

“Disagreement with their own bodies”.(S1-FG2)

“When they have very low self-esteem”.(S2-FG2)

3.1.2. Family Risk Factors

“Lack of care and attention”.(S3-FG1)

“It may also be that, for example, one is not taking care of the children and they look for someone other than the father or mother. That can be a bad thing”.(S5-FG5)

“It may be that they do not want him in the family”.(S3-FG2)

“Lack of family affection”.(S2-FG2)

“Having differences in treatment between children”.(S3-FG3)

“Maybe they think they don’t love them”.(S2-FG5)

“The problems that happen inside the house”.(S5-FG3)

“So, let’s say the dads fight and can’t talk about anything normal”.(S4-FG3)

“When there is not a good relationship between husband and wife”.(S3-FG5)

“But also fights between couples affect and lead to getting angry with them for no reason, having arguments for no reason”.(S3-FG5)

3.1.3. Community Risk Factors

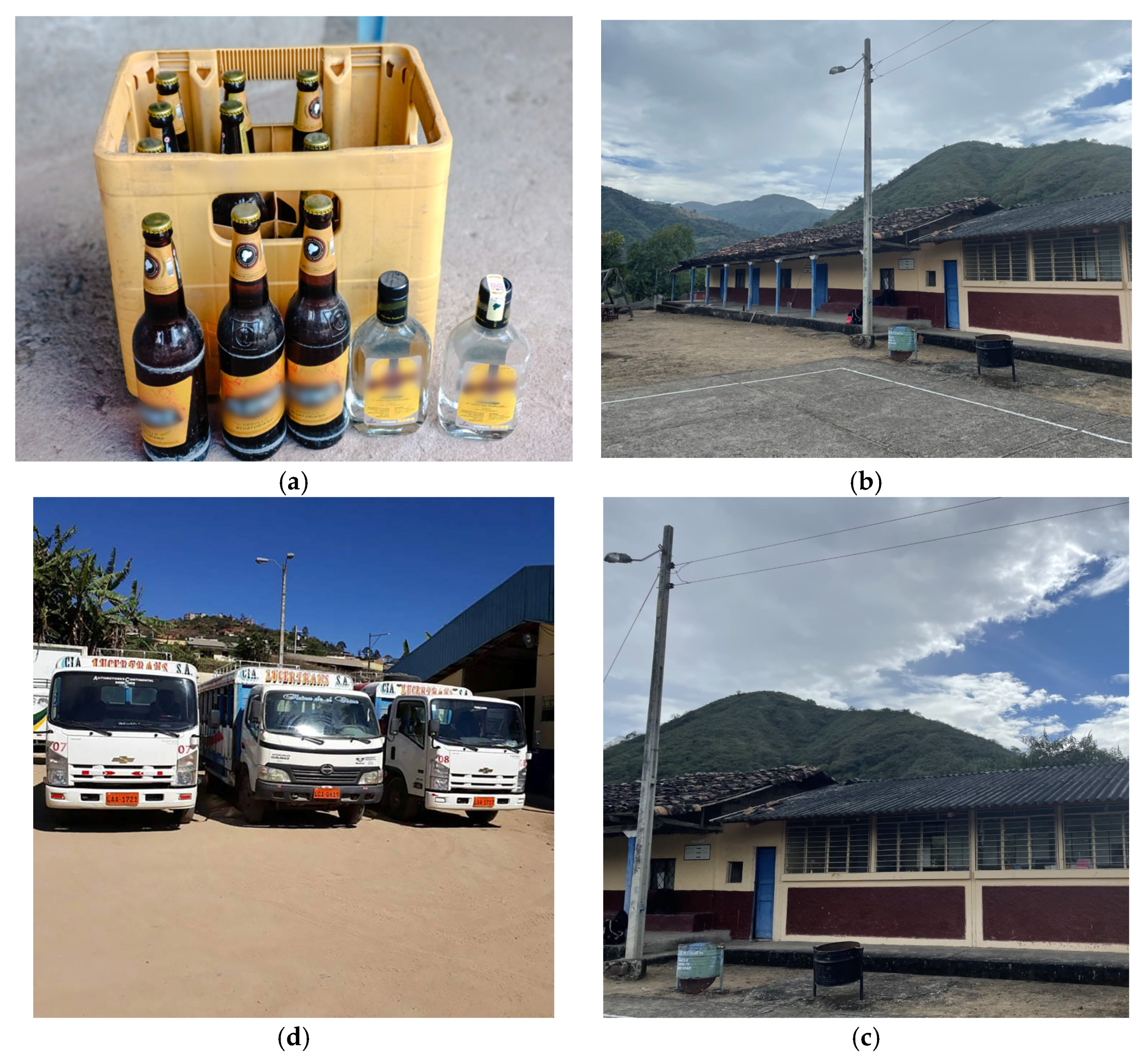

“Of course, here adolescents from the age of 14 practically already drink alcohol”.(S1-FG2)

“The truth is that here yes, in all the communities here, from the age of 14 they already use what are drinks, drinks, tobacco, everything”.(S3-FG2)

“I sell alcohol, but minors buy a few because they don’t have money to buy anything if the adult provides it and whoever drinks that, and if not, they don’t have money to buy. With the fair ones he goes to the school that they give to his parents. I believe that the parents are not going to give their sons 10 dollars in cash so that he can go drink”.(S6-FG4)

“Here the consumption is alcohol or tobacco but not drugs”.(S6-FG4)

“Respect the body, do not harm the body. Teach them to respect their bodies”.(S4-FG1)

“I say that it is important to have information aids, that is, informative talks to adolescents about how bad it is to consume alcoholic beverages, drugs, all that, talks because there is nothing here and I think practically nowhere”.(S1-FG2)

“(…) Transportation, we pay for that and it does affect us financially”.(S7-FG4)

“Teenagers have to make a little more effort to study because of the distance”.(S3-FG5)

“So, my nephew already told him: no daddy, I don’t study anymore, why? If you don’t have enough time to work, you don’t have to pay, if you don’t have money to pay the tickets, how am I going to go?”.(S6-FG3)

“And for the sector where I live, I don’t live for this sector but for the other side of the creek, because I live there with my brothers and I don’t know who wants to do evil, that is, and for that reason. I feel sad to see my son, because it scares me that something might happen to him along the way”.(S8-FG3)

“We need to have the school closer or maybe have a collective transport”.(S2-FG1)

“So far this year, we pray to have secondary education here, we ask for transportation, but not anymore, there is no solution. If we talk to the mayor, let him be the one who supports us with half the cost of transportation, for a few days he supported us to cover these study expenses in the boys’ studies, they gave us half, but not now”.(S7-FG3)

“They get up early to receive the education, now is different as it was, also they need transportation from here to Cariamanga and it is far away”.(S8-FG3)

“We want something different and sometimes we believe that everything is possible. We tried to put the high school here, we tried it with the teacher, they looked for documents, the time passed without answer, other families continue to spend much more money and we didn’t find a solution”.(S5-FG3)

“They say it’s better to work, but at the same time it’s a shame because it happens to them like someone who only finished primary school, and no one knows more about it”.(S8-FG3)

“When there is concern that there is no way to spend the money, when they see the father or mother suffering. How are they going to get their money and now how do they go to school, they already ask for this and there is none, so they think it is better to be working”.(S7-FG3)

“They decide and want to continue studying, but seeing how we are at home, they prefer to work and the adolescents say that it is better to help improve family life. But they don’t do it because they want to. The same to give them time at home to study. They can’t at the same time want to study, but as you can see there isn’t. There is no way to give them”.(S5-FG3)

“Well, let’s say the conditions are not very good, (...) because in reality there is a lack for study, a lack for medicine, (…) with money there is everything, with money there is education, everything that is needed. But instead now, with the poor, well, one lacks everything, (…) it lacks for education, for medicine. Maybe even to eat. So if one is missing”.(S8-FG4)

“But for example here let’s say people study so sometimes they have something like a ticket for food and on the other hand there are also those who don’t, no, we don’t have, so we can’t give them the study like this”.(S4-FG5)

3.2. Photo-Voice

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations Population Fund. State of World Population 2011: People and Possibilities in a World of 7 Billion; United Nations Publication Fund: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Children’s Fund. The State of the World’s Children 2021: On My Mind—Promoting, Protecting and Caring for Children’s Mental Health; United Nations Children’s Fund: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Baena, V.C. Community mental health, primary health care and health promoting universities in Ecuador. Rev. Panam. Salud Publica/Pan Am. J. Public Health 2018, 42, e162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fregoso-Borrego, D.; Vera-Noriega, J.Á.; Duarte-Tánori, K.G.; Peña-Ramos, M.O. Familia, escuela y comunidad en relación a la violencia escolar en secundaria: Revisión sistemática. Entramado 2021, 17, 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas-Molina, B.; Pérez-Albéniz, A.; Solbes-Canales, I.; Ortuño-Sierra, J.; Fonseca-Pedrero, E. Bullying, Cyberbullying and Mental Health: The Role of Student Connectedness as a School Protective Factor. Psychosoc. Interv. 2021, 31, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A.M.; Ford, J. Transgender adolescent and young adult suicide: A bioecological perspective. Nurs. Inq. 2022, 29, e12476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttazzoni, A.; Doherty, S.; Minaker, L. How Do Urban Environments Affect Young People’s Mental Health? A Novel Conceptual Framework to Bridge Public Health, Planning, and Neurourbanism. Public Health Rep. 2022, 137, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, M.; Ghazinour, M.; Hammarström, A. Different uses of Bronfenbrenner’s ecological theory in public mental health research: What is their value for guiding public mental health policy and practice? Soc. Theory Health 2018, 16, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papachristou, E.; Frangou, S.; Reichenberg, A. Expanding conceptual frameworks: Life course risk modelling for mental disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2013, 206, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, G.A.; Smallegange, E.; Coetzee, A.; Hartog, K.; Turner, J.; Jordans, M.J.D.; Brown, F.L. Correction to: A Systematic Review of the Evidence for Family and Parenting Interventions in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Child and Youth Mental Health Outcomes. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2019, 28, 2326–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, M.; Adams, S.; Whiteman, N.; Hughes, J.; Reilly, P.; Dogra, N. Whose Responsibility is Adolescent’s Mental Health in the UK? Perspectives of Key Stakeholders. School Ment. Health 2018, 10, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauer, S. Partizipative Forschung und Gestaltung als Antwort auf empirische und forschungspolitische Herausforderungen der Arbeitsforschung? Ind. Bezieh. 2017, 3, 253–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Burris, M.A. Photovoice: Concept, Methodology, and Use for Participatory Needs Assessment. Health Educ. Behav. 1997, 24, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C. Youth Participation in Photovoice as a Strategy for Community Change. J. Community Pract. 2006, 14, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodgate, R.; Zurba, M.; Tennent, P. Worth a Thousand Words? Advantages, Challenges and Opportunities in Working with Photovoice as a Qualitative Research Method with Youth and their Families. Forum Qual. Soz. 2017, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Grijalva, M.J.; Villacis, A.G.; Ocaña-Mayorga, S.; Yumiseva, C.A.; Moncayo, A.L.; Baus, E.G. Comprehensive Survey of Domiciliary Triatomine Species Capable of Transmitting Chagas Disease in Southern Ecuador. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2015, 9, e0004142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Gómez, A.; Cevallos, W.; Grijalva, M.J.; Silva-Ayçaguer, L.C.; Tamayo, S.; Jacobson, J.O.; Costales, J.A.; Jiménez-Garcia, R.; Hernández-Barrera, V.; Serruya, S.; et al. Social factors associated with use of prenatal care in Ecuador. Rev. Panam. Salud Pública 2016, 40, 341–346. [Google Scholar]

- Suprapto, N.; Sunarti, T.; Suliyanah; Wulandari, D.; Hidayaatullaah, H.N.; Adam, A.S.; Mubarok, H. A systematic review of photovoice as participatory action research strategies. Int. J. Eval. Res. Educ. 2020, 9, 675–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspers, P.; Corte, U. What is Qualitative in Qualitative Research. Qual. Sociol. 2019, 42, 139–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Content Analysis Theoretical Foundation, Basic Procedures and Software Solution. 2014, p. 143. Available online: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-395173 (accessed on 30 November 2022).

- Moore, L.; Chersich, M.F.; Steen, R.; Reza-Paul, S.; Dhana, A.; Vuylsteke, B.; Lafort, Y.; Scorgie, F. Community empowerment and involvement of female sex workers in targeted sexual and reproductive health interventions in Africa: A systematic review. Glob. Health 2014, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, A.S.; Scott, K.; Sarriot, E.; Kanjilal, B.; Peters, D.H. Unlocking community capabilities across health systems in low- and middle-income countries: Lessons learned from research and reflective practice. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladonna, K.; Mylopoulos, M.; Steenhof, N. Combining adaptive expertise and (critically) reflective practice to support the development of knowledge, skill, and society. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 2022, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younker, T.; Radunovich, H.L. Farmer mental health interventions: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasil, A.R.; Osborn, T.L.; Venturo-Conerly, K.E.; Wasanga, C.; Weisz, J.R. Conducting global mental health research: Lessons learned from Kenya. Glob. Ment. Health 2021, 8, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heise, L.; Greene, M.E.; Opper, N.; Stavropoulou, M.; Harper, C.; Nascimento, M.; Zewdie, D.; Darmstadt, G.L.; Greene, M.E.; Hawkes, S.; et al. Gender inequality and restrictive gender norms: Framing the challenges to health. Lancet 2019, 393, 2440–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, B.J.; Smith, A.D.A.C.; Dunn, E.C. Statistical Modeling of Sensitive Period Effects Using the Structured Life Course Modeling Approach (SLCMA). In Sensitive Periods of Brain Development and Preventive Interventions; Andersen, S.L., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 215–234. ISBN 978-3-031-04473-1. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, N.; Kiviruusu, O.; Karvonen, S.; Rahkonen, O.; Huurre, T. Pathways from problems in adolescent family relationships to midlife mental health via early adulthood disadvantages—A 26-year longitudinal study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0178136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, M.L.; Aguerrebere, M.; Elliott, P.F. Depression in rural communities and primary care clinics in Chiapas, Mexico. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2019, 9, 103–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suso-Ribera, C.; Mora-Marín, R.; Hernández-Gaspar, C.; Pardo-Guerra, L.; Pardo-Guerra, M.; Belda-Martínez, A.; Palmer-Viciedo, R. Suicide in Castellon, 2009-2015: Do sociodemographic and psychiatric factors help understand urban-rural differences? Rev. Psiquiatr. Salud Ment. 2018, 11, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensi, M.M.; Criscuolo, M.; Vai, E.; Rogantini, C.; Orlandi, M.; Ballante, E.; Zanna, V.; Mazzoni, S.; Balottin, U.; Borgatti, R. Perceived and observed family functioning in adolescents affected by restrictive eating disorders. Fam. Relat. 2022, 71, 724–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés, M.D.L.; Morales, L.A.; Rojas, J.L.; Villa, M. De Patrones de consumo de alcohol y percepciones de riesgo en estudiantes mexicanos. Rev. Iberoam. Psicol. Salud 2021, 12, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MInisterio de Salud Pública del Ecuador (MSP). Plan Estratégico Nacional de Salud Mental 2015—2017; Comisión de Salud Mental: Quito, Ecuador, 2014; pp. 2–92. [Google Scholar]

- Romano, S.T.; Nelson-Nuñez, J.; LaVanchy, G.T. Rural water provision at the state-society interface in Latin America. Water Int. 2021, 46, 802–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavytska, T. Transferring Language Learning and Teaching From Face-to-Face to Online Settings; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

| Deductive Category Assignments | Definition | Anchor Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Personal risk factor | Parents can identify those individuals’ behaviors that make adolescents more likely to develop a mental health issue. | “He or she looks stressed”; “He or she consumes alcohol”; “He or she looks depressive” |

| Family risk factor | Parents can identify problems in family functioning relating to cohesion, routines or communication that make adolescents more likely to develop a mental health issue. | “There is abuse or maltreatment in the family”; “There is inadequate supervision” |

| Community risk factor | Parents can identify norms favorable to alcohol or substance use and a lack of economic opportunity that make adolescents more likely to develop a mental health issue. | “Adolescents drink alcohol with adults”; “We have problems with our economy” |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baus, E.; Carrasco-Tenezaca, M.; Frey, M.; Medina-Maldonado, V. Risk Factors for the Mental Health of Adolescents from the Parental Perspective: Photo-Voice in Rural Communities of Ecuador. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2205. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032205

Baus E, Carrasco-Tenezaca M, Frey M, Medina-Maldonado V. Risk Factors for the Mental Health of Adolescents from the Parental Perspective: Photo-Voice in Rural Communities of Ecuador. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(3):2205. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032205

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaus, Esteban, Majo Carrasco-Tenezaca, Molly Frey, and Venus Medina-Maldonado. 2023. "Risk Factors for the Mental Health of Adolescents from the Parental Perspective: Photo-Voice in Rural Communities of Ecuador" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 3: 2205. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032205

APA StyleBaus, E., Carrasco-Tenezaca, M., Frey, M., & Medina-Maldonado, V. (2023). Risk Factors for the Mental Health of Adolescents from the Parental Perspective: Photo-Voice in Rural Communities of Ecuador. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), 2205. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032205