Climate Change and Health: Local Government Capacity for Health Protection in Australia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Executives’ Perception of the Local Government Environmental Health Role

3.2. Local Government Environmental Health and Climate Change

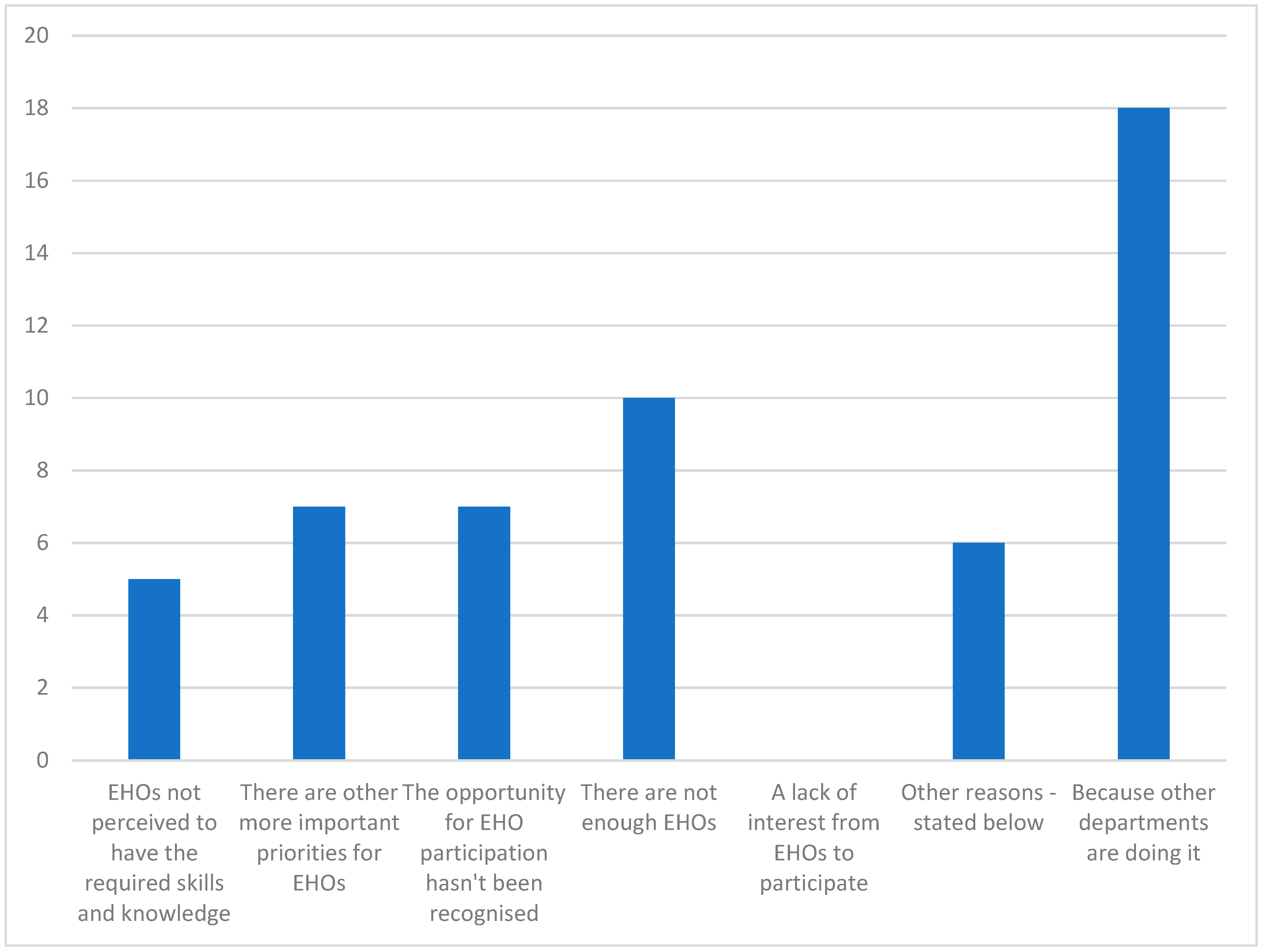

- Project team member (1).

- Plan development—provider of advice/information (1).

- Plan implementation—responsible for designated tasks (0 chose this option).

- Other (2 responses—specifically “Specialist advice only” and “Provision of information to food businesses/health premises, etc.”).

- No time to develop climate change adaptation/mitigation as a discrete task. It is built into any other relevant task such as the Stormwater Management Plan.

- Currently not a major focus of the city.

- Separate Environmental Services team in Sustainable Assets.

- Lack of understanding of the role they can play.

- We have a Sustainability Officer.

- Climate change plans are managed by other environmental specialists within council.

- Considerable cost shifting to Council EHOs over the years and EHOs have several priorities they are juggling.

- EHO provide advice to staff where their primary role is in climate change/mitigation planning.

- We have a Natural Environment Program that has developed a carbon reduction strategy. EHOs work in a regulatory space, I’m not sure how we could make the jump to climate change planning without a regulatory framework in place.

- As far as I know the city has not identified this as an area of priority.

- Lack of capacity due to workload.

4. Discussion

- mental health;

- vector-borne disease and/or zoonoses;

- food quality and safety;

- water quality and safety;

- air pollution and aeroallergens;

- people who are socio-economically disadvantaged;

- rural and geographically isolated communities;

- people with disabilities;

- children and older people;

- pregnant women and unborn children;

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people [32].

- the source of water that can be used for commercial food preparation and premises sanitation;

- the required volumes needed to meet sanitation and production requirements;

- the required water treatments;

- time and costs for treatments and analyses;

- loss of income due to delays and meeting regulatory requirements;

- overall viability of the business and its value to the local community.

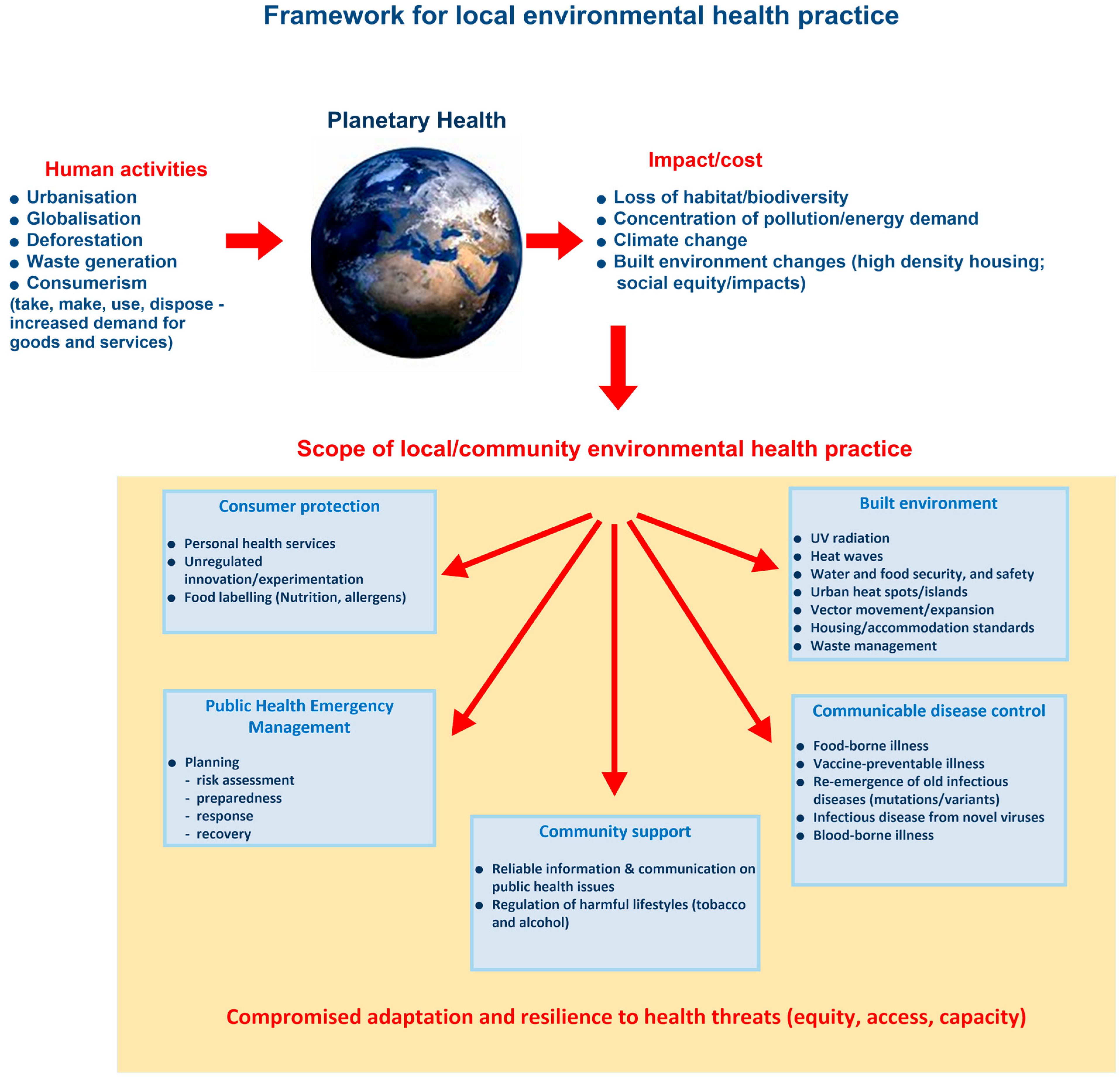

- Consumer protection—ensuring compliance safeguards and required safety standards are in place for consumers.

- Public health emergency management—ensuring the appropriate preparation for (including testing of preparations), response to, and recovery from health impacts of emergencies.

- Community support—assisting consumers and the broader community in health decision making, raising awareness of public health risks, and improving community public health knowledge.

- Communicable disease control—minimizing the risk of disease transmitted through food, water, people, and vectors.

- Built environment—reducing human activities’ impact on the local receiving environments, protecting the community from environmental hazards, and enhancing infrastructure to support health.

5. Conclusions

- State governments review their public health priorities and revise the legislation to reflect these priorities and remove conflicting and prescriptive legislative obligations.

- State government climate adaptation planning integrates with and supports local council adaptation planning.

- Council executive management recognize the potential for EHOs to increase their capacity for climate change adaptation planning in public health and provide the opportunities to do so.

- EHOs recognize that they are the public health adaptive capacity for climate change, and engage with councils’ climate change planning processes and adapt environmental health services to reflect the level of community risk based on the framework for local environmental health practice

- Environmental health officers are the qualified public health practitioners in local government, and they are a critical resource in supporting communities to adapt to the public health impacts of climate change.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Whitmee, S.; Haines, A.; Beyrer, C.; Boltz, F.; Capon, A.G.; de Souza Dias, B.F.; Ezeh, A.; Frumkin, H.; Gong, P.; Head, P. The Rockefeller Foundation–Lancet Commission on planetary health. Safeguarding human health in the Anthropocene epoch: Report of The Rockefeller Foundation–Lancet Commission on planetary health. Lancet 2015, 386, 1973–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. COP24 Special Report: Health and Climate Change; 9241514973; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- McMichael, A.J. Earth as Humans’ Habitat: Global Climate Change and the Health of Populations. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2014, 2, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheehan, M.C.; Fox, M.A.; Kaye, C.; Resnick, B. Integrating health into local climate response: Lessons from the US CDC Climate-Ready States and Cities Initiative. Environ. Health Perspect. 2017, 125, 094501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, T.A.; Fox, M.A. Global to local: Public health on the front lines of climate change. Am. J. Public Health 2018, 108, S74–S75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Beggs, P.J.; Bambrick, H.; Berry, H.L.; Linnenluecke, M.K.; Trueck, S.; Alders, R.; Bi, P.; Boylan, S.M.; Green, D. The MJA–Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: Australian policy inaction threatens lives. Med. J. Aust. 2018, 209, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- enHealth. Strategic Plan 2020–2023; Environmental Health Standing Committee (enHealth) of the Australian Health Protection Principal Committee, Ed.; Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, S.E.; Ford, J.D.; Berrang-Ford, L.; Biesbroek, R.; Ross, N.A. Enabling local public health adaptation to climate change. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 220, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deparment of Agriculture Water and the Environment. National Climate Resilience and Adaptation Strategy 2021 to 2025; Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2021.

- Municipal Association of Victoria. Policy & Advocacy: Environment and Water. Available online: https://www.mav.asn.au/what-we-do/policy-advocacy/environment-water (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- Local Government Association of South Australia. LGA Climate Commitment Action Plan 2021–2023; Local Government Association of South Australia: Adelaide, Australia, 2021.

- Local Government Association of Queensland. Climate Risk Management Framework for Queensland Local Government. Available online: https://www.qld.gov.au/environment/climate/climate-change/resources/local-government (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- LGNSW. Planning for Climate Change. Available online: https://lgnsw.org.au/Public/Public/Policy/Planning-for-Climate-Change.aspx (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Western Australia Local Government Association. Climate Change Template and Tools: WALGA’s Climate Change Action Framework. Available online: https://walga.asn.au/policy-advice-and-advocacy/environment/climate-change/templates-and-tools.aspx (accessed on 11 August 2022).

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 2012. Glossary of terms. In Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation: Special Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Field, C.B., Barros, V., Stocker, T.F., Qin, D., Dokken, D.J., Ebi, K.L., Mastrandrea, M.D., Mach, K.J., Plattner, G.-K., Allen, S.K., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 555–564. [Google Scholar]

- Ebi, K.L.; Semenza, J.C. Community-based adaptation to the health impacts of climate change. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2008, 35, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, V.; Smith, J.; Fawkes, S. Public Health Practice in Australia: The Organised Effort, Allen & Unwin: Crows Nest, Australia, 2014, 2nd ed. [Google Scholar]

- Whiley, H.; Willis, E.; Smith, J.; Ross, K. Environmental health in Australia: Overlooked and underrated. J. Public Health 2019, 41, 470–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, J.C.; Whiley, H.; Ross, K.E. The New Environmental Health in Australia: Failure to Launch? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Environmental Health Australia. Environmental Health Course Accreditation Policy; Environmental Health Australia: Brisbane, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Curtin University. Environmental Health Graduate Diploma. Available online: https://www.curtin.edu.au/study/offering/course-pg-graduate-diploma-in-environmental-health--gd-envhl/ (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Griffith University. Environmental Health. Available online: https://www.griffith.edu.au/study/health/environmental-health?location=intl (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Flinders University. Environmental Health. Available online: https://www.flinders.edu.au/study/courses/postgraduate-environmental-health (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Ortman, S.G.; Lobo, J.; Smith, M.E. Cities: Complexity, theory and history. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0243621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Profile of Australia’s Population; Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Araos, M.; Austin, S.E.; Berrang-Ford, L.; Ford, J.D. Public health adaptation to climate change in large cities: A global baseline. Int. J. Health Serv. 2016, 46, 53–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, S.F.; Morris, A.; Grant, B. Mind the gap: Australian local government reform and councillors’ understandings of their roles. Commonw. J. Local Gov. 2016, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirst, T.M.; Carpini, J.A.; Timming, A.R.; Notebaert, L. Western Australia’s Local Government Act 25 years on and under review: A qualitative study of local government Chief Executive Officers. Aust. J. Public Adm. 2021, 80, 809–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, J.; Walker, E.; McKenzie, F.H. Recruiting CEOs in local government: A ‘game of musical chairs’? Aust. J. Public Adm. 2017, 76, 480–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, A.J.; Bambrick, H.J.; Friel, S. Is enough attention given to climate change in health service planning? An Australian perspective. Glob. Health Action 2014, 7, 23903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victorian Department of Health and Human Services. Tackling Climate Change and its Impacts on Health through Municipal Public Health and Wellbeing Planning, Guidance for Local Governmen; Victorian Department of Health and Human Services: Melbourne, Australia, 2020.

- NSW Health. Climate Change Impacts on Our Health and Wellbeing; NSW Health Department: Sydney, Australia, 2022.

- Asia Pacific Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. Food Safety, Climate Change, and the Role of WHO; WHO Regional Office for South-East Asia: New Delhi, India, 2019.

- Duchenne-Moutien, R.A.; Neetoo, H. Climate Change and Emerging Food Safety Issues: A Review. J. Food Prot. 2021, 84, 1884–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Statutory or Regulatory Functions | NSW | QLD | SA | TAS | VIC | WA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Management/provision of water supplies | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No |

| Management of waste and sanitation (including domestic wastewater and recycling) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Food safety regulation (food-borne illness) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Regulation of businesses of public health interest (recreational waters) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Regulation of lodging houses/prescribed accommodation | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Prevention and control of infectious diseases (arboviral diseases) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Statutory Function/ Service | Public Health Impacts from Climate Change | Risk Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Management/ provision of water supplies | Water quality and/or safety |

|

| Management of waste and sanitation (including domestic wastewater and its recycling) |

| |

| Food safety regulation (food-borne illness) | Food quality and safety |

|

| Regulation of businesses of public health interest (recreational waters) | Recreational water quality and/or safety |

|

| Regulation of lodging houses/prescribed accommodation | Heat stress |

|

| Prevention and control of infectious diseases (arboviral diseases) | Vector-borne disease and/or zoonoses |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Smith, J.C.; Whiley, H.; Ross, K.E. Climate Change and Health: Local Government Capacity for Health Protection in Australia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1750. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20031750

Smith JC, Whiley H, Ross KE. Climate Change and Health: Local Government Capacity for Health Protection in Australia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(3):1750. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20031750

Chicago/Turabian StyleSmith, James C., Harriet Whiley, and Kirstin E. Ross. 2023. "Climate Change and Health: Local Government Capacity for Health Protection in Australia" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 3: 1750. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20031750

APA StyleSmith, J. C., Whiley, H., & Ross, K. E. (2023). Climate Change and Health: Local Government Capacity for Health Protection in Australia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), 1750. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20031750