The Interface between the State and NGOs in Delivering Health Services in Zimbabwe—A Case of the MSF ART Programme

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.1.1. Global Overview of Aid in Healthcare Systems

1.1.2. Aid in African Healthcare Systems

1.1.3. Aid in Zimbabwean Healthcare Systems

1.2. Statement of the Problem

1.3. Theory

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting and Overview of the MSF ART Programme Transition to MoHCC

2.2. Sampling Technique

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

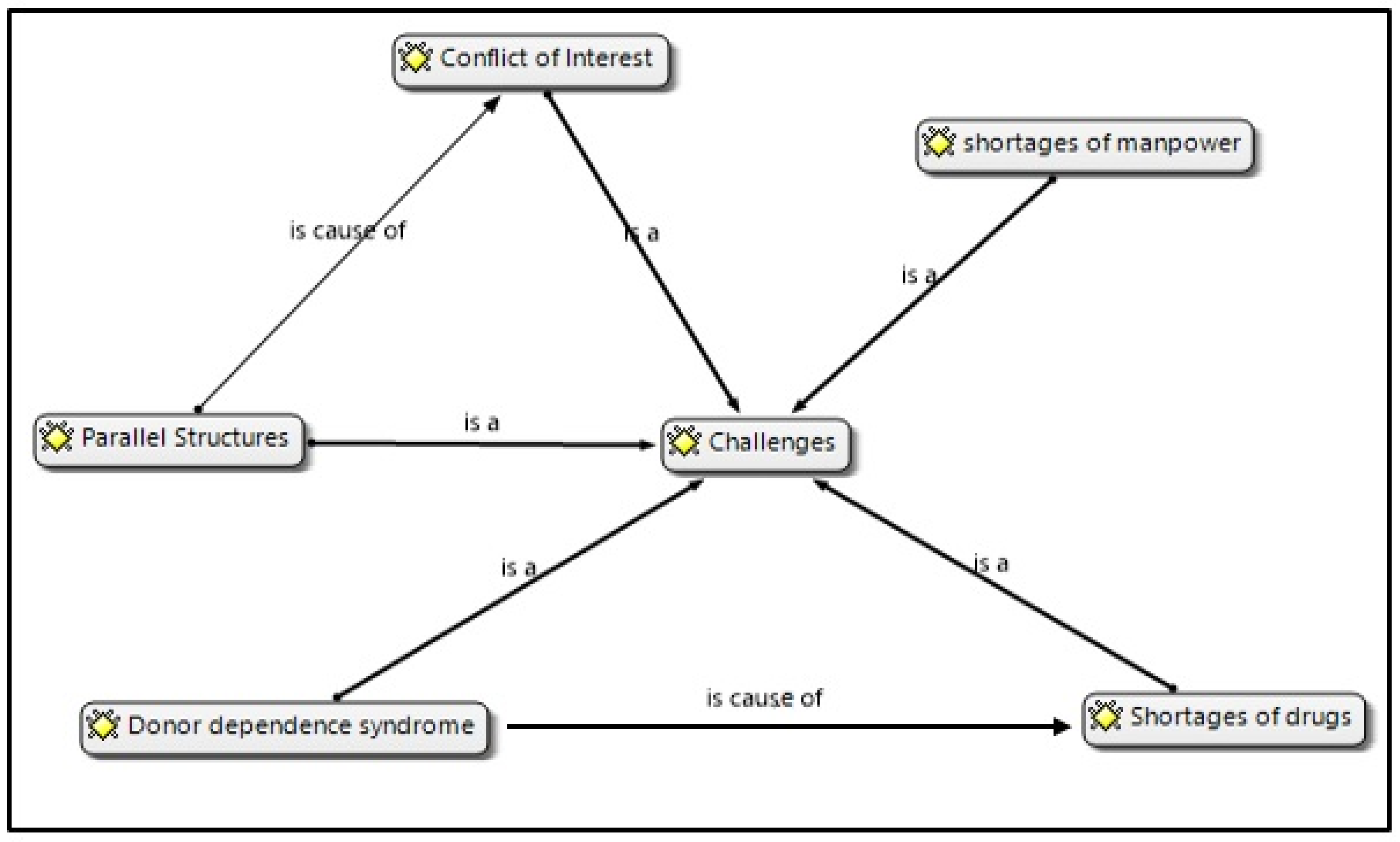

3.1. Parallel Structures

For your own information, the MSF staff were paid hefty salaries in US dollars, and yet we had the same qualifications. Those who were paid in Zimbabwean dollars were wallowing in poverty and were looked down upon by the MSF staff.

There were no gaps in the ART programme as such, but this programme superseded all other health programmes in the district because MSF supported it with incentives. This disadvantaged the performance of the district in programmes like EPI—there was under performance.

The MSF had a challenge of not following the ministry’s protocols and policies regarding monitoring and evaluation systems. For example, the organisation used Follow Up and Care of HIV infected and AIDS (FUCHIA) data collection and analysis system which contrasted with what the MoHCC used.

…they came with their own policies which sometimes went against the government policies with regards to ART initiation or had no or what can I say, the government had no idea of all those things. That was a challenge sometimes they came and say we initiate patients when CD4 is 1, 2, 3 whereas the government did not put into consideration that CD4 count threshold. Can that be made a policy and so forth? So, in terms of those things sometimes things were not flowing well according to the government policy.

As we were passing from a pure MSF supported approach to this mentoring of these nurses and capacity building it meant obviously that we are going to reduce the staff and that a number would lose their job. MSF staff would lose their job. So, I understood that in some instances, some staff employed by MSF would be kind of reluctant to transfer these competencies because it would mean now losing their job while MoHCC staff would now take up the knowledge and experience.

3.2. Shortage of Manpower (Personnel Resources)

We used to have many nurses. So, MSF moved out and retrenched most of the nurses who used to help us in terms of labour here, so we are now understaffed, and we can feel the strain.

Now, there is a shortage of doctors because now there are only three doctors. We can have one doctor going for workshops, one going for male circumcision and only one doctor running the whole hospital, the Outpatient, the wards and the same doctor is the one running the district, she is the DMO (District Medical Officer) with that big responsibility on her shoulders, she is going to be in the office going for the meeting, this and that, it is so much and tiresome. So, the patients will be waiting only to be told at the end of the day that the doctor is no longer coming but with MSF the doctors had to takeover.

We are doing this for the beneficiaries, because of the beneficiaries we are down scaling, that is happening now with MSF. What they are [MSF] doing is they are letting more and more people go, they are retrenching because they want to still maintain that status which I have told you that 85 to 90% must go to the beneficiaries ten to fifteen per cent then go to salaries and administration.

3.3. Shortages of Drugs

Medication is no longer available. The main thing that we are doing is to say can you please go and buy this one, but by the time MSF was here most of the drugs were here. Now we are only running with few drugs. When MSF was still here, we were also going to get drugs, even for OIs, which were given for free.

About the sustainability of this programme, the major determining factor shall be finances to procure drugs. Given the financial situation in Zimbabwe it is going to be difficult to foresee this programme being sustainable, unless if they are going to bring another donor to help in that regard, I don’t know whether it will be sustainable now that they have withdrawn supplying the medication.

MSF had some mobile programmes for HIV testing to give people free education on HIV/AIDS, but now we don’t see those mobile teams which were created by MSF again.

3.4. Donor Dependency Syndrome

I think the government should find another organisation or supportive partner who should be catering for some drugs or so on or MSF is supposed to come back in the district.I can feel that we are going to have a problem of sustainability. The main obstacle, of course, continues to be money. The tests are expensive, the machines are expensive, and they require highly qualified staffs like the MSF who were here. On that note I would like to encourage the government to find another partner or bring MSF back.

4. Discussion

4.1. Parallel Structures

4.2. Shortage of Personnel Resources

4.3. Shortages of Drugs

4.4. Donor Dependency Syndrome

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tshiyoyo, M. The Changing Roles of Non-Governmental Organizations in Development in South Africa: Challenges and Opportunities. In Global Perspectives on Non-Governmental Organizations; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, R.S.; Brass, J.N.; Shermeyer, A.; Grossman, N. Reported effects of Nongovernmental Organisations (NGOs) in health and education service provision: The role of NGO–Government relations and other factors. Dev. Policy Rev. 2023, e12737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GoZ, Zimbabwe National Health Financing Policy. Resourcing Pathways to Universal Health Coverage: Equity and Quality in Health- Leaving No One Behind; Government of Zimbabwe: Harare, Zimbabwe, 2016.

- Mhazo, A.T.; Maponga, C.C. The political economy of health financing reforms in Zimbabwe: A scoping review. Int. J. Equity Health 2022, 21, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidia, K.K. The future of health in Zimbabwe. Glob. Health Action 2018, 11, 1496888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medecins Sans Frontières. MSF Progress Under Threat: Perspectives on the HIV Treatment Gap; Medecins Sans Frontières: Brussels, Belgium, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Magocha, B.; Mutekwe, E. Narratives and interpretations of the political economy of Zimbabwe’s development aid trajectory, 1980–2013. TD: J. Transdiscipl. Res. South. Afr. 2021, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjønneland, E.N. From Aid Effectiveness to Poverty Reduction Is Foreign Donor Support to SADC Improving? Botswana Institute for Development Policy Analysis (BIDPA): Gaborone, Botswana, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Report 2005: International Cooperation at a Crossroads: Aid, Trade and Security in an Unequal World; UNDP: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. Development Co-Operation Report 2013: Ending Poverty; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Burnside, C.; Dollar, D. Aid, policies, and growth. Am. Econ. Rev. 2000, 90, 847–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterly, W. Are aid agencies improving? Econ. Policy 2007, 22, 634–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, R.; Subramanian, A. What Undermines Aid’s Impact on Growth? National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Moyo, D. Why foreign aid is hurting Africa. Wall Str. J. 2009, 21, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Collier, P.; Dollar, D. Can the World Cut Poverty in Half? How Policy Reform and Effective Aid Can Meet International Development Goals. World Dev. 2001, 29, 1787–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J. The End of Poverty: How We Can Make It Happen in Our Lifetime; Penguin UK: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ovaska, T. The failure of development aid. Cato J. 2003, 23, 175. [Google Scholar]

- Pomerantz, P.R. Aid Effectiveness in Africa: Developing Trust between Donors and Governments; Lexington Books: Lanham, MD, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gukurume, S. Interrogating foreign aid and the sustainable development conundrum in African countries: A Zimbabwean experience of debt trap and service delivery. Int. J. Politics Good Gov. 2012, 3, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Fragile States 2014: Domestic Revenue Mobilisation in Fragile States. Better Policies for Better Lives; OECD: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Amusa, K.; Monkam, N.; Viegi, N. Foreign aid and Foreign direct investment in Sub-Saharan Africa: A panel data analysis. Econ. Res. South Afr. (ERSA) 2016, 612, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- UNCTAD. Development, Economic Development in Africa Report 2014: Catalysing Investment for Transformative Growth in Africa; UNCTAD: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, G. Why Africa is Poor: And What Africans Can Do about It; Penguin Random House South Africa: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ejughemre, U. Donor Support and the Impacts on Health System Strengthening in Sub-Saharan Africa: Assessing the Evidence through a Review of the Literature. Am. J. Public Health Res. 2013, 1, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chuma, J.; Mulupi, S.; McIntyre, D. Providing Financial Protection and Funding Health Service Benefits for the Informal sSector: Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa; London, UK: KEMRI—Wellcome Trust Research Programme; University of Cape Town: Cape Town, South Africa.

- Mbacke, C.S.M. African leadership for sustainable health policy and systems research. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2013, 13, S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. The World Health Report: Health Systems Financing: The Path to Universal Coverage: Executive Summary; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010.

- Riddell, R.C. Does foreign aid work. Doing Good Doing Better 2009, 47, 47–80. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnenkamp, P.; Öhler, H. Throwing foreign aid at HIV/AIDS in developing countries: Missing the target? World Dev. 2011, 39, 1704–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, F. Re-Living the Second Chimurenga: Memories from the Liberation Struggle in Zimbabwe; African Books Collective: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nyazema, N.Z. The Zimbabwe Crisis and the Provision of Social Services. J. Dev. Soc. 2010, 26, 233–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murisa, T. Social Development in Zimbabwe; DFZ: Harare, Zimbabwe, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bonarjee, M. Three Decades of Land Reform in Zimbabwe: Perspectives of Social-Justice and Poverty Alleviation; The Bergen Resource Centre for International Development Seminar: Bergen, Norway, 2013; pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Monyau, M.M.; Bandara, A. Zimbabwe 2015. Afr. Econ. Outlook 2015, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munyuki, E.; Jasi, S. Capital Flows in the Health Care Sector in Zimbabwe: Trends and Implications for the Health System; EQUINET: Harare, Zimbabwe, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zimbabwe, United Nations Development Programme. Millennium Development Goals Progress Report. Arch. Dis. Child. 2012, 100, S1. [Google Scholar]

- AfDB. Zimbabwe: Country Brief 2011–2013. South A and Fragile States Unit Regional Department; AfDB: Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, C.J. Zimbabwe: Why is One of the World’s Least-Free Economies Growing so Fast? Cato Inst. Policy Anal. 2013, 722, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Salama, P.; Ha, W.; Negin, J.; Muradzikwa, S. Post-crisis Zimbabwe’s innovative financing mechanisms in the social sectors: A practical approach to implementing the new deal for engagement in fragile states. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 2014, 14, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- National AIDS Council of Zimbabwe. NAC Co-Ordinating the Multi-Sectoral Response to HIV and AIDS; National AIDS Council of Zimbabwe: Harare, Zimbabwe, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zimbabwe Ministry of Economic Planning & Investment Promotion. Zimbabwe Medium Term Plan, 2011–2015: Towards Sustainable Inclusive Growth, Human Centred Development, Transformation and Poverty Reduction; Ministry of Economic Planning & Investment Promotion: Harare, Zimbabwe, 2011.

- ZimVAC Zimbabwe. Vulnerability Assessment Committee: Market Assessment Report; Food and Nutrion Council: Harare, Zimbabwe, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- MoHCC. The Zimbabwe Health Sector Investment Case (2010–2012): Accelerating Progress Towards the Millennium Development Goals; Zimbabwe Government: Harare, Zimbabwe, 2010.

- Taylor, S.J.; Bogdan, R.; DeVault, M. Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods: A Guidebook and Resource; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Stake, R.E. Qualitative Research: Studying How Things Work; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Burnett, G.; Lingam, G.I. Postgraduate research in Pacific education: Interpretivism and other trends. Prospects 2012, 42, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyo, N.; Maharaj, P. Liberty Mambondiani Food challenges facing people living with HIV/AIDS in Zimbabwe. Afr. J. AIDS Res. 2017, 16, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, F.; Ferreyra, C.; Bernasconi, A.; Ncube, L.; Taziwa, F.; Marange, W.; Wachi, D.; Becher, H. Tracing defaulters in HIV prevention of mother-to-child transmission programmes through community health workers: Results from a rural setting in Zimbabwe. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2015, 18, 20022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, E.; Laurie, C. Doing Real Research: A Practical Guide to Social Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Babbie, E. The Practice of Social Research Thomson; Wadsworth: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cresswell, J. Research Design (International Student Edition): Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches, 4th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fereday, J.; Muir-Cochrane, E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2006, 5, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teaster, P.B.; Roberto, K.A.; Dugar, T.A. Intimate Partner Violence of Rural Aging Women. In Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Gerontological-Society-of-America, Washington, DC, USA, 19–23 November 2004; pp. 636–648. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Wildemuth, B.M. Qualitative Analysis of Content; Sage: Newcastle, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Friese, S. Qualitative Data Analysis with ATLAS.ti; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012; ISBN 9780857021311. [Google Scholar]

- Burnard, P.; Gill, P.; Stewart, K.; Treasure, E.; Chadwick, B. Analysing and presenting qualitative data. Br. Dent. J. 2008, 204, 429–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuzeid, F. Foreign Aid and the ‘Big Push’Theory: Lessons from sub-Saharan Africa. Stanf. J. Int. Relat. 2009, XI, 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Mwega, F.M. A Case Study of Aid Effectiveness in Kenya: Volatility and Fragmentation of Foreign Aid, with a Focus on Health. In The Brookings Global Economy and Development; Wolfensohn Centre for Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sridhar, D. Seven Challenges in International Development Assistance for Health and Ways Forward. J. Law Med. Ethic 2010, 38, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojikutu, B.; Makadzange, A.T.; Gaolathe, T. Scaling up ART treatment capacity: Lessons learned from South Africa, Zimbabwe, and Botswana. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2008, 10, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasschaert, F.; Koole, O.; Zachariah, R.; Lynen, L.; Manzi, M.; Van Damme, W. Short and long term retention in antiretroviral care in health facilities in rural Malawi and Zimbabwe. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012, 12, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wandeler, G.; Keiser, O.; Pfeiffer, K.; Pestilli, S.; Fritz, C.; Labhardt, N.D.; Mbofana, F.; Mudyiradima, R.; Emmel, J.; Egger, M.; et al. Outcomes of Antiretroviral Treatment Programs in Rural Southern Africa. Am. J. Ther. 2012, 59, e9–e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zihindula, G.; John, R.A.; Gumede, D.M.; Gavin, M.R. A review on the contributions of NGOs in addressing the shortage of healthcare professionals in rural South Africa. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2019, 5, 1674100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stegman, P.; Avolos, A.; Jefferies, K.; Iyer, P.; Formson, C.; Mosime, W.; Forsythe, S. Transitional Financing and the Response to HIV/AIDS in Botswana: A Country Analysis; Health Policy Initiative: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Seeling, S.; Mavhunga, F.; Thomas, A.; Adelberger, B.; Ulrichs, T. Barriers to access to antiretroviral treatment for HIV-positive tuberculosis patients in Windhoek, Namibia. Int. J. Mycobacteriology 2014, 3, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chevo, T.; Bhatasara, S. HIV and AIDS Programmes in Zimbabwe: Implications for the Health System. ISRN Immunol. 2012, 2012, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addo-Atuah, J.; Gourley, D.; Gourley, G.; White-Means, S.I.; Womeodu, R.J.; Faris, R.J.; Addo, N.A. Accessibility of antiretroviral therapy in Ghana: Convenience of access. SAHARA-J: J. Soc. Asp. HIV/AIDS 2012, 9, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wouters, E.; Van Damme, W.; van Rensburg, D.; Masquillier, C.; Meulemans, H. Impact of community-based support services on antiretroviral treatment programme delivery and outcomes in resource-limited countries: A synthetic review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012, 12, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferradini, L.; Jeannin, A.; Pinoges, L.; Izopet, J.; Odhiambo, D.; Mankhambo, L.; Karungi, G.; Szumilin, E.; Balandine, S.; Fedida, G.; et al. Scaling up of highly active antiretroviral therapy in a rural district of Malawi: An effectiveness assessment. Lancet 2006, 367, 1335–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, R.N.; Bauer, P. From Subsistence to Exchange and Other Essays. Foreign Aff. 2000, 79, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karikari, K. Where Has Aid Taken Africa? Re-Thinking Development; Media Foundation for West Africa: Accra, Ghana, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, I.; Routh, S.; Bitran, R.; Hulme, A.; Avila, C. Where will the money come from? Alternative mechanisms to HIV donor funding. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Resch, S.; Ryckman, T.; Hecht, R. Funding AIDS programmes in the era of shared responsibility: An analysis of domestic spending in 12 low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Glob. Health 2015, 3, e52–e61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, S. Does Aid Improve Public Service Delivery? UNU—WIDER: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, S.; Seeley, J.; Ezati, E.; Wamai, N.; Were, W.; Bunnell, R. Coming back from the dead: Living with HIV as a chronic condition in rural Africa. Health Policy Plan. 2007, 22, 344–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda-Parr, S.; Lopes, C.; Malik, K. Capacity for Development—New Solutions to Old Problems. Environ. Manag. Health 2002, 13, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Magocha, B.; Molope, M.; Palamuleni, M.; Saruchera, M. The Interface between the State and NGOs in Delivering Health Services in Zimbabwe—A Case of the MSF ART Programme. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 7137. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20237137

Magocha B, Molope M, Palamuleni M, Saruchera M. The Interface between the State and NGOs in Delivering Health Services in Zimbabwe—A Case of the MSF ART Programme. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(23):7137. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20237137

Chicago/Turabian StyleMagocha, Blessing, Mokgadi Molope, Martin Palamuleni, and Munyaradzi Saruchera. 2023. "The Interface between the State and NGOs in Delivering Health Services in Zimbabwe—A Case of the MSF ART Programme" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 23: 7137. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20237137

APA StyleMagocha, B., Molope, M., Palamuleni, M., & Saruchera, M. (2023). The Interface between the State and NGOs in Delivering Health Services in Zimbabwe—A Case of the MSF ART Programme. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(23), 7137. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20237137