Exploring the Lived Experiences of Vulnerable Females from a Low-Resource Setting during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Approach and Study Settings

2.2. Sampling

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Ethical Considerations

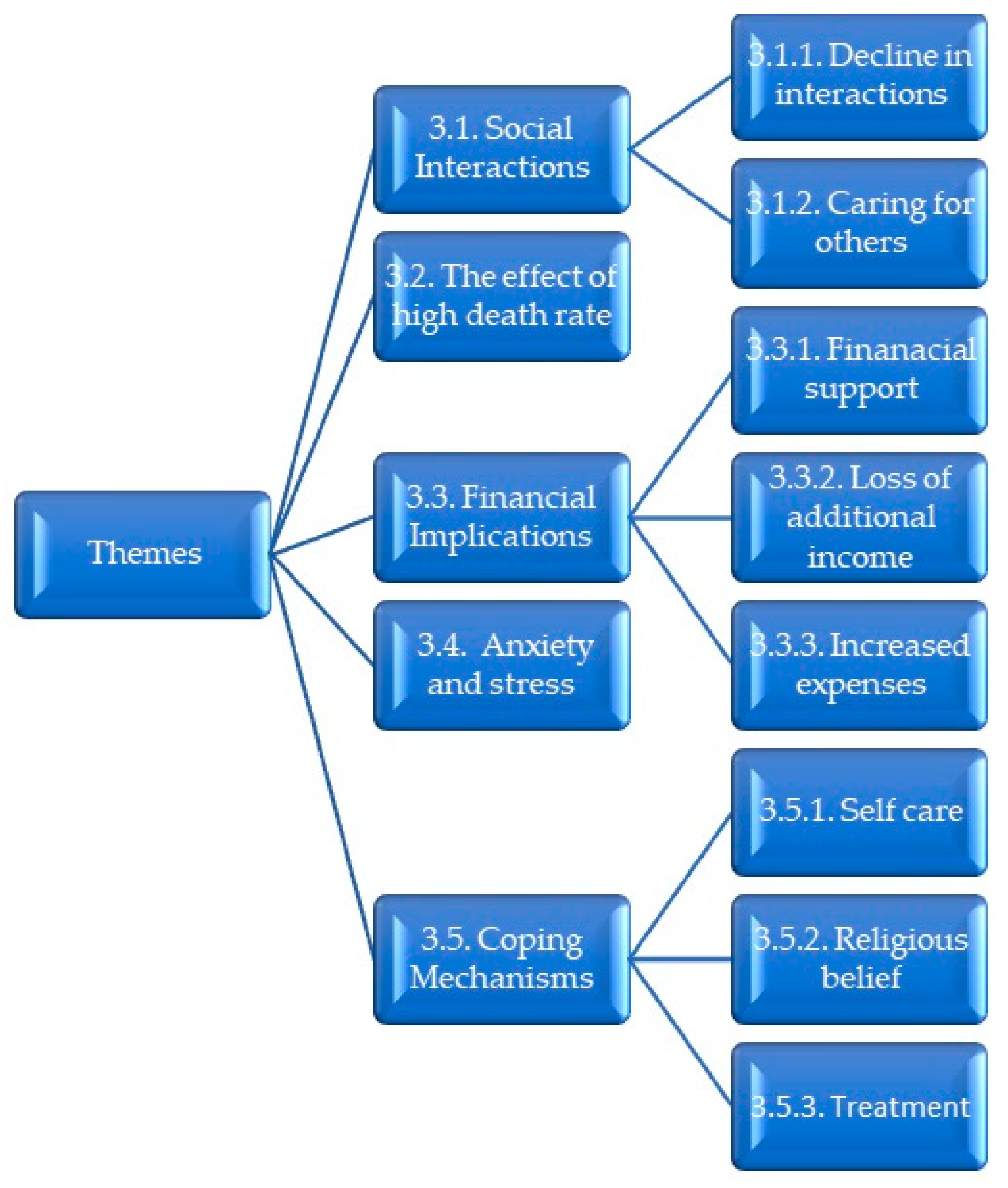

3. Results

3.1. Social Interactions

3.1.1. Decline in Interactions

“Our social interaction was affected badly because we could not visit each other the way we were used to, no visitation no checking upon each other, nothing. Some friendships died during that period, but there was nothing that we could have done, each person was protecting him or herself.” (P9: Age, 79)

“Our social life was also very disturbed, with all the masks we could not even hear each other when we talk, sometimes we could not recognize each other in the passages because of masks.” (P11: Age, 89)

“I saw changes in my grandchildren, children like to go out and play and do all outside activities, but with the restrictions they could not. I noticed changes in their behaviour; those changes were not good. They started acting reserved and down, there was nothing I could do; I started allowing them to go to the park and play. I ensured that they wore masks, and they would go straight to the bath when they come back and change clothes immediately.” (P12: Age, 68)

“Remaining indoors was difficult for me. I have arthritis that gets worse if I sit or remain in one position for too long, so I was in constant pain because I could not go out for my regular walks around the neighbourhood. I could not socialise with the neighbours as well.” (P10: Age, 76)

3.1.2. Caring for Others

“Some of the neighbours here stay alone and we are the only people they have to help them. Because of Ubuntu (humanity) we could not just neglect them. With those few visits, we still wore masks and sanitized.” (P10: Age, 76)

“I had neighbours that were constantly checking up on me and were taking good care of me, I never felt alone. I would still communicate with my family via cell phone calls and WhatsApp.” (P3: Age, 60)

3.2. The Effect of High Death Rates

“Another thing that was very sad is the restrictions at funerals. It was very difficult because only a certain number of people would go to funerals. During her (cousin’s) funeral, her coffin was wrapped in plastic and the coffin looked as if it was smaller than her. It was heart-breaking, that is what broke my heart the most, the way my cousin was buried. We also could not attend other family funerals outside of KZN because of COVID-19.” (P6: Age, 81)

“Two of my children got sick and one unfortunately passed away and he was infected with COVID-19. Planning the funeral was difficult and the limited number of people allowed to attend made it worse. As a family alone we are more than 50, it was very difficult to choose who comes to the funeral and who doesn’t.” (P11: Age, 89)

“The virus was very bad; I would cry for people. We did not know how it came. We never saw my aunt and uncle; we did not go to their funeral. My mother is 90 and she never got to see her sister’s funeral, we all never went there.” (P2: Age, 55)

3.3. Financial Implications

3.3.1. Financial Support

“It did not affect my income; I still got my pension grant with no issues.” (P9: Age, 79)

“I still got my retirement pension with no issues. My husband was also receiving the temporary UIF funds that they were receiving during the period they could not go to work. We still managed fine financially.” (P8: Age, 60)

“Financially, it was painful because there were some of my family members and neighbours that could not continue working and did not even receive their UIF money, that some people were receiving to support themselves during that period of being unable to work. It was difficult for them.” (P4: Age, 65)

“My son was able to support me financially. There were also some people from a Pick ‘n Pay supermarket from Joburg that bought groceries for me, and they sent food regularly. My son made sure that we had everything we needed. They would always phone and check, “Mom, you got this? What did you cook today? What did you eat today?” They were all there for me. I can say they always checked on us, always.” (P1: Age, 63)

3.3.2. Loss of Additional Income

“Other people lost their employment; it was a difficult time. My husband’s company was also affected, but fortunately they never lost their jobs.” (P5: Age, 54)

“The most difficult thing was the inability to continue with the work that we were doing. We have a group of ladies and children that run a sewing project of different clothing garments and sell them every Sunday at the marketplace in town. The sewing project had to stop because of restrictions. We were left with nothing to do. Finances were also affected, we were no longer selling our garments, that meant no money was coming in, we only were dependent on the government pension. Everything needed money—from groceries, medications, rent, electricity, and everything, but there was so little that we had at that time. It was difficult.” (P12: Age, 68)

“I still received my pension. It is my children that lost their employment and business, but still that affected me because they were no longer able to give me money as they used to before.” (P3: Age, 60)

3.3.3. Additional Expenses

“Financially, it was bad because as they said, we were supposed to keep washing and keep cleaning ourselves and our households, so we needed extra money for all those cleaning things, that was a bit hard.” (P1: Age, 63)

“The only challenge was that we used more money during that time because if you are in the house all day you tend to eat more, get more cravings and you want to snack all the time because there is nothing keeping you busy. We would watch TV all day, use all the home appliances all the time, and that increased the electricity bill and water bill.” (P8: Age, 60)

3.4. Anxiety and Stress

“During that time, you couldn’t go out and at times you couldn’t go to do your grocery shopping at any time. We had to wear a mask all the time. Those restrictions we had made me feel very sad and upset, but in another way, it was for our own safety as older people, the older we are, the easier we can get sick, I always thought about that.” (P1: Age, 63)

“It was difficult to also go to the shops, especially for us old people who do not know how to buy online and get your things delivered. I felt like freedom was very limited, we could not do most of the things that we wanted to do and were used to doing.” (P9: Age, 79)

“It was very hard when we heard of all the people in hospitals, it was hard. One minute we would be talking, the next minute you would hear something has happened to someone close to you. It was very hard and hurting because we are a family…. it was also difficult for me to go to hospital. It was like we all are tied up.” (P2: Age, 55)

3.5. Coping Mechanisms

“Most of the time, my family would phone me. Even my kids would phone me every day. My son, my daughter-in-law, and my daughter would phone me every day and check on us, So, I think those phone calls also helped a lot. I would know they are still in contact and they are still worrying about us.” (P1: Age, 63)

3.5.1. Self-Care

“I love cooking and baking, so I was constantly on the stove all the time, and that helped me to keep myself busy and have less time to worry.” (P8: Age, 60)

“I tried to continue with the sewing project from my house, but it was very difficult without the other ladies. I just needed something to do just to pass time. I then started sewing masks after seeing that they were in demand as everyone had to wear them. The masks sewing project ran successfully for a whole year, we had started to make money, until unfortunately I started developing arthritis that made it very difficult for me to continue. My coping mechanism was continuing with my sewing project and teaching my kids and grandkids to sew as well.” (P12: Age, 68)

3.5.2. Religious Belief

“I just prayed. I prayed so much; I prayed every day. So, you would say prayer was my coping mechanism, it helped me a lot.” (P1: Age, 63)

“I am a born-again Christian, if it was not for God I don’t know if I would have survived. What we could not handle we just told God, we needed God to give us strength and give us wisdom and tolerance for each other.” (P6: Age, 81)

3.5.3. Treatment

“We regularly used some of the home remedies that have been known to prevent and treat flu, for example, ginger, garlic, lemon and honey. I never got sick with any other illnesses during that time.” (P11: Age, 89)

“I also took multivitamin tablets to keep my immune system strong enough.” (P8: Age, 60)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cucinotta, D.; Vanelli, M. WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Biomed. 2020, 91, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, M.; Shrestha, A.D.; Stojanac, D.; Miller, L.J. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on women’s mental health. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2020, 23, 741–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Xu, R.; Volkow, N.D. Increased risk of COVID-19 infection and mortality in people with mental disorders: Analysis from electronic health records in the United States. World Psychiatry 2021, 20, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, E.; Patterson, S.; Maxwell, K.; Blake, C.; Pérez, R.B.; Lewis, R.; McCann, M.; Riddell, J.; Skivington, K.; Wilson-Lowe, R.; et al. COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on social relationships and health. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2022, 76, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The South African Government. Declaration of a National State of Disaster. Available online: https://www.gov.za/documents/disaster-management-act-declaration-national-state-disaster-covid-19-coronavirus-16-mar (accessed on 11 June 2023).

- South African College of Applied Psychology. The Shocking State of Mental Health in South Africa in 2018. Available online: https://www.sacap.edu.za/blog/counselling/mental-health-south-africa/ (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Pillay, Y. State of mental health and illness in South Africa. S. Afr. J. Psychol. 2019, 49, 463–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posel, D.; Oyenubi, A.; Kollamparambil, U. Job loss and mental health during the COVID-19 lockdown: Evidence from South Africa. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0249352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hugelius, K.; Harada, N.; Marutani, M. Consequences of visiting restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic: An integrative review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 121, 104000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Man, J.; Smith, M.R.; Schneider, M.; Tabana, H. An exploration of the impact of COVID-19 on mental health in South Africa. Psychol. Health Med. 2022, 27, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, B.; Acharya, T. The COVID-19 Pandemic and its Effect on Mental Health in USA—A Review with Some Coping Strategies. Psychiatr. Q. 2020, 91, 1135–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. Mental Health and Psycosocial Considerations during the COVID-19 Outbreak; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Connor, J.; Madhavan, S.; Mokashi, M.; Amanuel, H.; Johnson, N.R.; Pace, L.E.; Bartz, D. Health risks and outcomes that disproportionately affect women during the Covid-19 pandemic: A review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 266, 113364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibaut, F.; van Wijngaarden-Cremers, P.J.M. Women’s Mental Health in the Time of COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Glob. Womens Health 2020, 1, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, D. The impact of Covid-19 pandemic on elderly mental health. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 35, 1466–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffel, T.; Doran, P.; Goff, M.; Lang, L.; Lewis, C.; Phillipson, C.; Yarker, S. Covid-19 and inequality: Developing an age-friendly strategy for recovery in low income communities. Qual. Ageing 2020, 21, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HelpAge International. Older Women and Social Protection: Statement to the 63rd Commission on the Status of Women. Available online: https://age-platform.eu/sites/default/files/HelpAge_Statement_to_CSW2019.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2023).

- Irigoyen-Camacho, M.E.; Velazquez-Alva, M.C.; Zepeda-Zepeda, M.A.; Cabrer-Rosales, M.F.; Lazarevich, I.; Castaño-Seiquer, A. Effect of Income Level and Perception of Susceptibility and Severity of COVID-19 on Stay-at-Home Preventive Behavior in a Group of Older Adults in Mexico City. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 7418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adab, P.; Haroon, S.; O’Hara, M.E.; Jordan, R.E. Comorbidities and COVID-19. BMJ 2022, 377, o1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adebisi, Y.A.; Ekpenyong, A.; Ntacyabukura, B.; Lowe, M.; Jimoh, N.D.; Abdulkareem, T.O.; Lucero-Prisno, D.E. COVID-19 Highlights the Need for Inclusive Responses to Public Health Emergencies in Africa. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020, 104, 449–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguse, S.; Wassenaar, D. Mental health and COVID-19 in South Africa. S. Afr. J. Psychol. 2021, 51, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Communicable Diseases. Latest Confirmed Cases of COVID-19 in South Africa (6 March 2022). Available online: https://www.nicd.ac.za/latest-confirmed-cases-of-covid-19-in-south-africa-6-march-2022/ (accessed on 16 June 2023).

- Made, F.; Utembe, W.; Wilson, K.; Naicker, N.; Tlotleng, N.; Mdleleni, S.; Mazibuko, L.; Ntlebi, V.; Ngwepe, P. Impact of level five lockdown on the incidence of COVID-19: Lessons learned from South Africa. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2021, 39, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ports, K.A.; Haffejee, F.; Mosavel, M.; Rameshbabu, A. Integrating cervical cancer prevention initiatives with HIV care in resource-constrained settings: A formative study in Durban, South Africa. Glob. Public Health 2015, 10, 1238–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennink, M.; Kaiser, B.N. Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: A systematic review of empirical tests. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 292, 114523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesch, R. Qualitative Research: Analysis Types and Software Tools; RoutledgeFalmer: Bristol, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage Publications: NewBury Park, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, B.C.; Harris, I.B.; Beckman, T.J.; Reed, D.A.; Cook, D.A. Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research: A Synthesis of Recommendations. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. Generalization in quantitative and qualitative research: Myths and strategies. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2010, 47, 1451–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghanibashi-Mansourieh, A. Assessing the anxiety level of Iranian general population during COVID-19 outbreak. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2020, 51, 102076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osofsky, J.D.; Osofsky, H.J.; Mamon, L.Y. Psychological and social impact of COVID-19. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2020, 12, 468–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nxumalo, C.T.; Tokwe, L.; Ngcobo, S.J.; Gam, N.P.; McHunu, G.G.; Makhado, L. Exploring the perceptions and lived experiences of family members living with people diagnosed with COVID-19 in South Africa: A descriptive phenomenological study. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2023, 18, 2247622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forbes, M.K.; Krueger, R.F. The Great Recession and Mental Health in the United States. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 7, 900–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Round, A.; Nanda, S.; Rankin, L. Helping Households in Debt; Institute for Public Policy Research: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, R.; Westaway, D. Mental health rescue effects of women’s outdoor tourism: A role in COVID-19 recovery. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 85, 103041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujan, M.S.H.; Tasnim, R.; Islam, M.S.; Ferdous, M.Z.; Haghighathoseini, A.; Koly, K.N.; Pardhan, S. Financial hardship and mental health conditions in people with underlying health conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic in Bangladesh. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, A.; Poltarykhin, A.; Alekhina, N.; Nikiforov, S.; Gayazova, S. The relationship between religious beliefs and coping with the stress of COVID-19. HTS Teol. Stud./Theol. Stud. 2021, 77, a6487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeRossett, T.; LaVoie, D.J.; Brooks, D. Religious Coping Amidst a Pandemic: Impact on COVID-19-Related Anxiety. J. Relig. Health 2021, 60, 3161–3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.R.C.; Damiano, R.F.; Marujo, R.; Nasri, F.; Lucchetti, G. The role of spirituality in the COVID-19 pandemic: A spiritual hotline project. J. Public Health 2020, 42, 855–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daily, J.W.; Zhang, X.; Kim, D.S.; Park, S. Efficacy of Ginger for Alleviating the Symptoms of Primary Dysmenorrhea: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. Pain. Med. 2015, 16, 2243–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ried, K.; Toben, C.; Fakler, P. Effect of garlic on serum lipids: An updated meta-analysis. Nutr. Rev. 2013, 71, 282–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Research Participant | Age | Ethnicity | Relationship Status | Number of Children | Persons in Household | Source of Income |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P01 | 63 | Indian | Widowed | 2 | 2 | Government pension |

| P02 | 55 | Indian | Widowed | 1 | 5 | Government pension |

| P03 | 55 | Black | Single | 7 | 5 | Government pension |

| P04 | 65 | Black | Single | 2 | 2 | Government pension |

| P05 | 54 | Black | Married | 2 | 4 | Disability grant |

| P06 | 81 | Caucasian | Married | 7 | 6 | Government pension |

| P07 | 74 | Black | Cohabiting | 1 | 3 | Government pension |

| P08 | 60 | Black | Married | 3 | 5 | Retirement pension |

| P09 | 79 | Black | Single | 1 | 2 | Government pension |

| P10 | 76 | Black | Divorced | None | 4 | Government pension |

| P11 | 89 | Black | Single | None | 3 | Government pension |

| P12 | 68 | Black | Married | 6 | 6 | Government pension |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Haffejee, F.; Maharajh, R.; Sibiya, M.N. Exploring the Lived Experiences of Vulnerable Females from a Low-Resource Setting during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 7040. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20227040

Haffejee F, Maharajh R, Sibiya MN. Exploring the Lived Experiences of Vulnerable Females from a Low-Resource Setting during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(22):7040. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20227040

Chicago/Turabian StyleHaffejee, Firoza, Rivesh Maharajh, and Maureen Nokuthula Sibiya. 2023. "Exploring the Lived Experiences of Vulnerable Females from a Low-Resource Setting during the COVID-19 Pandemic" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 22: 7040. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20227040

APA StyleHaffejee, F., Maharajh, R., & Sibiya, M. N. (2023). Exploring the Lived Experiences of Vulnerable Females from a Low-Resource Setting during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(22), 7040. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20227040