Willingness for Medical Screening in a Dental Setting—A Pilot Questionnaire Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

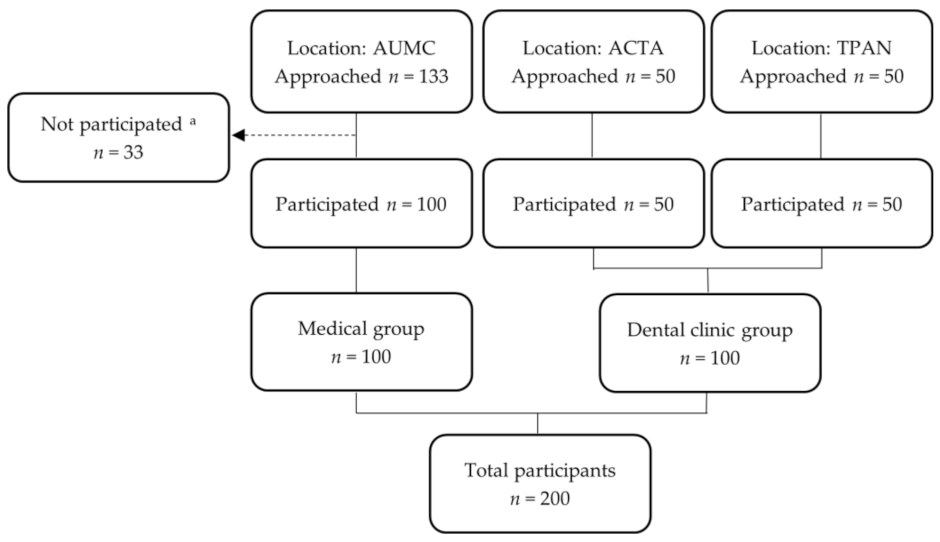

2.2. Settings and Participants

2.3. Questionnaire

- Are you open to having the dentist inform you whether you are at risk of developing diseases, such as diabetes and cardiovascular diseases?

- Are you open to having your dentist take a saliva test to determine the risk of cardiovascular disease?

- Are you open to having the dentist measure your blood pressure?

- Are you open to having the dentist measure your weight and height (BMI)?

- Are you open to having the dentist measure your blood glucose level using a finger prick?

- Are you open to having the dentist measure your cholesterol using a finger prick?

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Background Data

3.2. Primary Results

3.3. Secondary Results

3.4. Additional Comments

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Results

4.2. Interpretation

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

4.4. Generalizability

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Questionnaire with Their Dutch Translations (Italic)

- Age/Leeftijd:

- Sex/Geslacht: o Female/Vrouw o Male/Man o Other/Anderszins o Rather not say/Wens dit niet aan te geven

- Are you born in the Netherlands?/Bent u in Nederland geboren?

- ○

- Yes/Ja

- ○

- No/Nee

- Were both your parents born in the Netherlands?/Zijn uw beide ouders in Nederland geboren?

- ○

- Yes/Ja

- ○

- No/Nee

- Are you open to having the dentist inform you whether you are at risk of developing diseases, such as diabetes and cardiovascular diseases?/Staat u er voor open dat de tandarts u informeert als u risico loopt op het krijgen van mogelijke ziektes zoals diabetes en hart- en vaatziekten?

- ○

- Yes/Ja

- ○

- No/Nee

- Are you open to having your dentist take a saliva test to determine the risk of cardiovascular disease?/Staat u er voor open dat de tandarts bij u een speekseltest afneemt om het risico op hart- en vaatziekten vast te stellen?

- ○

- Yes/Ja

- ○

- No/Nee

- Are you open to having the dentist measure your blood pressure?/Staat u er voor open dat de tandarts uw bloeddruk meet?

- ○

- Yes/Ja

- ○

- No/Nee

- Are you open to having the dentist measure your weight and height (BMI)?/Staat u er voor open dat de tandarts uw gewicht en lengte (BMI) meet?

- ○

- Yes/Ja

- ○

- No/Nee

- Are you open to having the dentist measure your blood glucose level using a finger prick?/Staat u er voor open dat de tandarts met behulp van een vingerprik uw bloedsuikerwaarde meet?

- ○

- Yes/Ja

- ○

- No/Nee

- Are you open to having the dentist measure your cholesterol using a finger prick?/Staat u er voor open dat de tandarts met behulp van een vingerprik uw cholesterol meet?

- ○

- Yes/Ja

- ○

- No/Nee

References

- World Health Organization. Noncommunicable Diseases. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed on 2 July 2022).

- Goryakin, Y.; Thiebaut, S.P.; Cortaredona, S.; Lerouge, M.A.; Cecchini, M.; Feigl, A.B.; Ventelou, B. Assessing the future medical cost burden for the European health systems under alternative exposure-to-risks scenarios. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0238565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cesare, M. Global trends of chronic non-communicable diseases risk factors. Eur. J. Public Health 2019, 29, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, D.J.; Reddy, K.S. Noncommunicable diseases. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 1336–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderon-Larranaga, A.; Vetrano, D.L.; Onder, G.; Gimeno-Feliu, L.A.; Coscollar-Santaliestra, C.; Carfi, A.; Pisciotta, M.S.; Angleman, S.; Melis, R.J.F.; Santoni, G.; et al. Assessing and Measuring Chronic Multimorbidity in the Older Population: A Proposal for Its Operationalization. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2017, 72, 1417–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, M.C.; Crilly, M.; Black, C.; Prescott, G.J.; Mercer, S.W. Defining and measuring multimorbidity: A systematic review of systematic reviews. Eur. J. Public Health 2019, 29, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, D.L.B.; Oliveras-Fabregas, A.; Minobes-Molina, E.; de Camargo Cancela, M.; Galbany-Estragues, P.; Jerez-Roig, J. Trends of multimorbidity in 15 European countries: A population-based study in community-dwelling adults aged 50 and over. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2014, 37 (Suppl. S1), S81–S90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleicher, E.; Gerdes, C.; Petersmann, A.; Muller-Wieland, D.; Muller, U.A.; Freckmann, G.; Heinemann, L.; Nauck, M.; Landgraf, R. Definition, Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes Mellitus. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes 2022, 127, S1–S7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas 10th Edition. Available online: http://www.diabetesatlas.org (accessed on 4 February 2022).

- Ogurtsova, K.; Guariguata, L.; Barengo, N.C.; Ruiz, P.L.; Sacre, J.W.; Karuranga, S.; Sun, H.; Boyko, E.J.; Magliano, D.J. IDF diabetes Atlas: Global estimates of undiagnosed diabetes in adults for 2021. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2022, 183, 109118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Ley, S.H.; Hu, F.B. Global aetiology and epidemiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its complications. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2018, 14, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banday, M.Z.; Sameer, A.S.; Nissar, S. Pathophysiology of diabetes: An overview. Avicenna J. Med. 2020, 10, 174–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beulens, J.; Rutters, F.; Ryden, L.; Schnell, O.; Mellbin, L.; Hart, H.E.; Vos, R.C. Risk and management of pre-diabetes. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2019, 26, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, M.J. Microvascular and Macrovascular Complications of Diabetes. Clin. Diabetes 2008, 26, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faselis, C.; Katsimardou, A.; Imprialos, K.; Deligkaris, P.; Kallistratos, M.; Dimitriadis, K. Microvascular Complications of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2020, 18, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viigimaa, M.; Sachinidis, A.; Toumpourleka, M.; Koutsampasopoulos, K.; Alliksoo, S.; Titma, T. Macrovascular Complications of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2020, 18, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stirban, A.; Gawlowski, T.; Roden, M. Vascular effects of advanced glycation endproducts: Clinical effects and molecular mechanisms. Mol. Metab. 2014, 3, 94–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, C.; Davis, K.E.; Imrhan, V.; Juma, S.; Vijayagopal, P. Advanced Glycation End Products and Risks for Chronic Diseases: Intervening Through Lifestyle Modification. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2019, 13, 384–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Cardiovascular Diseases (CVDs). Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds) (accessed on 4 February 2022).

- Malakar, A.K.; Choudhury, D.; Halder, B.; Paul, P.; Uddin, A.; Chakraborty, S. A review on coronary artery disease, its risk factors, and therapeutics. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 16812–16823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, P.; Buring, J.E.; Badimon, L.; Hansson, G.K.; Deanfield, J.; Bittencourt, M.S.; Tokgozoglu, L.; Lewis, E.F. Atherosclerosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2019, 5, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacco, R.L.; Kasner, S.E.; Broderick, J.P.; Caplan, L.R.; Connors, J.J.; Culebras, A.; Elkind, M.S.; George, M.G.; Hamdan, A.D.; Higashida, R.T.; et al. An updated definition of stroke for the 21st century: A statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2013, 44, 2064–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemaitis, M.R.; Boll, J.M.; Dreyer, M.A. Peripheral Arterial Disease. In StatPearls; StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Timmis, A.; Townsend, N.; Gale, C.P.; Torbica, A.; Lettino, M.; Petersen, S.E.; Mossialos, E.A.; Maggioni, A.P.; Kazakiewicz, D.; May, H.T.; et al. European Society of Cardiology: Cardiovascular Disease Statistics 2019. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 12–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budreviciute, A.; Damiati, S.; Sabir, D.K.; Onder, K.; Schuller-Goetzburg, P.; Plakys, G.; Katileviciute, A.; Khoja, S.; Kodzius, R. Management and Prevention Strategies for Non-communicable Diseases (NCDs) and Their Risk Factors. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 574111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, W.H.; Ye, W.; Griffin, S.J.; Simmons, R.K.; Davies, M.J.; Khunti, K.; Rutten, G.E.; Sandbaek, A.; Lauritzen, T.; Borch-Johnsen, K.; et al. Early Detection and Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes Reduce Cardiovascular Morbidity and Mortality: A Simulation of the Results of the Anglo-Danish-Dutch Study of Intensive Treatment in People with Screen-Detected Diabetes in Primary Care (ADDITION-Europe). Diabetes Care 2015, 38, 1449–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piepoli, M.F.; Hoes, A.W.; Agewall, S.; Albus, C.; Brotons, C.; Catapano, A.L.; Cooney, M.T.; Corra, U.; Cosyns, B.; Deaton, C.; et al. 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts)Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur. Heart J. 2016, 37, 2315–2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association. 10. Cardiovascular Disease and Risk Management: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2020. Diabetes Care 2020, 43, S111–S134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verhulst, M.J.L.; Loos, B.G.; Gerdes, V.E.A.; Teeuw, W.J. Evaluating All Potential Oral Complications of Diabetes Mellitus. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanz, M.; Ceriello, A.; Buysschaert, M.; Chapple, I.; Demmer, R.T.; Graziani, F.; Herrera, D.; Jepsen, S.; Lione, L.; Madianos, P.; et al. Scientific evidence on the links between periodontal diseases and diabetes: Consensus report and guidelines of the joint workshop on periodontal diseases and diabetes by the International Diabetes Federation and the European Federation of Periodontology. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2018, 45, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beukers, N.; van der Heijden, G.; Su, N.; van der Galien, O.; Gerdes, V.E.A.; Loos, B.G. An examination of the risk of periodontitis for nonfatal cardiovascular diseases on the basis of a large insurance claims database. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2022, 51, 408–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, M.; Marco Del Castillo, A.; Jepsen, S.; Gonzalez-Juanatey, J.R.; D’Aiuto, F.; Bouchard, P.; Chapple, I.; Dietrich, T.; Gotsman, I.; Graziani, F.; et al. Periodontitis and cardiovascular diseases: Consensus report. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2020, 47, 268–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loos, B.G. Systemic effects of periodontitis. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2006, 4 (Suppl. S1), 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockhart, P.B.; Bolger, A.F.; Papapanou, P.N.; Osinbowale, O.; Trevisan, M.; Levison, M.E.; Taubert, K.A.; Newburger, J.W.; Gornik, H.L.; Gewitz, M.H.; et al. Periodontal disease and atherosclerotic vascular disease: Does the evidence support an independent association?: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2012, 125, 2520–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonel, Z.; Sharma, P. The Role of the Dental Team in the Prevention of Systemic Disease: The Importance of Considering Oral Health as Part of Overall Health. Prim. Dent. J. 2017, 6, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bays, H.E.; Chapman, R.H.; Grandy, S.; Group, S.I. The relationship of body mass index to diabetes mellitus, hypertension and dyslipidaemia: Comparison of data from two national surveys. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2007, 61, 737–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes-2015 abridged for primary care providers. Clin. Diabetes 2015, 33, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, S.; Allison, D.B.; Heymsfield, S.B.; Kelley, D.E.; Leibel, R.L.; Nonas, C.; Kahn, R. Waist circumference and cardiometabolic risk: A consensus statement from shaping America’s health: Association for Weight Management and Obesity Prevention; NAASO, the Obesity Society; the American Society for Nutrition; and the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2007, 30, 1647–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwani, S.I.; Khan, H.A.; Ekhzaimy, A.; Masood, A.; Sakharkar, M.K. Significance of HbA1c Test in Diagnosis and Prognosis of Diabetic Patients. Biomark. Insights 2016, 11, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, M.A.; Ahmed, A.S.; Durand, R.; Tran, S.D. Saliva as a diagnostic tool for oral and systemic diseases. J. Oral Biol. Craniofac. Res. 2016, 6, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiongco, R.E.; Bituin, A.; Arceo, E.; Rivera, N.; Singian, E. Salivary glucose as a non-invasive biomarker of type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2018, 10, e902–e907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonel, Z.; Yahyouche, A.; Jalal, Z.; James, A.; Dietrich, T.; Chapple, I.L.C. Patient acceptability of targeted risk-based detection of non-communicable diseases in a dental and pharmacy setting. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonel, Z.; Sharma, P.; Yahyouche, A.; Jalal, Z.; Dietrich, T.; Chapple, I.L. Patients’ attendance patterns to different healthcare settings and perceptions of stakeholders regarding screening for chronic, non-communicable diseases in high street dental practices and community pharmacy: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e024503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creanor, S.; Millward, B.A.; Demaine, A.; Price, L.; Smith, W.; Brown, N.; Creanor, S.L. Patients’ attitudes towards screening for diabetes and other medical conditions in the dental setting. Br. Dent. J. 2014, 216, E2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gotzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; Initiative, S. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int. J. Surg. 2014, 12, 1495–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayhew, D.; Mendonca, V.; Murthy, B.V.S. A review of ASA physical status-historical perspectives and modern developments. Anaesthesia 2019, 74, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenberg, B.L.; Kantor, M.L.; Jiang, S.S.; Glick, M. Patients’ attitudes toward screening for medical conditions in a dental setting. J. Public Health Dent. 2012, 72, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yonel, Z.; Cerullo, E.; Kroger, A.T.; Gray, L.J. Use of dental practices for the identification of adults with undiagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus or non-diabetic hyperglycaemia: A systematic review. Diabet. Med. 2020, 37, 1443–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrich, C.G.; Araujo, M.W.B.; Lipman, R.D. Prediabetes and Diabetes Screening in Dental Care Settings: NHANES 2013 to 2016. JDR Clin. Trans. Res. 2019, 4, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2009, 32 (Suppl. S1), S62–S67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Diabetes. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/diabetes (accessed on 2 July 2022).

- Greenberg, B.L.; Glick, M.; Frantsve-Hawley, J.; Kantor, M.L. Dentists’ attitudes toward chairside screening for medical conditions. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2010, 141, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, A.E.; Caplan, D.J.; Lee, J.Y.; Paynter, L.; Gizlice, Z.; Champagne, C.; Ammerman, A.S.; Agans, R. Dentists’ attitudes about their role in addressing obesity in patients: A national survey. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2010, 141, 1307–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friman, G.; Hultin, M.; Nilsson, G.H.; Wardh, I. Medical screening in dental settings: A qualitative study of the views of authorities and organizations. BMC Res. Notes 2015, 8, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Total Study Population (n = 200) | Medical Group (n = 100) | Dental Clinic Group (n = 100) | p-Value * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 47.7 ± 17.8 | 55.9 ± 16.2 | 39.6 ± 15.6 | <0.001 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 104 (52.0) | 57 (57.0) | 47 (47.0) | 0.157 |

| Female | 96 (48.0) | 43 (43.0) | 53 (53.0) | |

| Cultural background | ||||

| Dutch | 110 (55.0) | 71 (71.0) | 39 (39.0) | <0.001 |

| Non-Dutch | 90 (45.0) | 29 (29.0) | 61 (61.0) | |

| T2DM a | ||||

| Yes | 20 (10.0) | 20 (20.0) | 0 (0.0) | N.T. |

| No | 180 (90.0) | 80 (80.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| CVD a | ||||

| Yes | 21 (10.5) | 21 (21.0) | 0 (0.0) | N.T. |

| No | 179 (89.5) | 79 (79.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Other diseases | 65 (32.5) | 65 (65.0) | 0 (0.0) | N.T. |

| Questions | Total Study Population (n = 200) | Medical Group (n = 100) | Dental Clinic Group (n = 100) | p-Value * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1. Are you open to having the dentist inform you whether you are at risk of developing diseases, such as diabetes and cardiovascular diseases? | ||||

| Yes No | 182 (91.0) 18 (9.0) | 91 (91.0) 9 (9.0) | 91 (91.0) 9 (9.0) | 1.000 |

| Q2. Are you open to having your dentist take a saliva test to determine the risk of cardiovascular disease? | ||||

| Yes No | 181 (90.5) 19 (9.5) | 94 (94.0) 6 (6.0) | 87 (87.0) 13 (13.0) | 0.091 |

| Q3. Are you open to having the dentist measure your blood pressure? | ||||

| Yes No | 178 (89.0) 22 (11.0) | 87 (87.0) 13 (13.0) | 91 (91.0) 9 (9.0) | 0.366 |

| Q4. Are you open to having the dentist measure your weight and height (BMI)? | ||||

| Yes No | 161 (80.5) 39 (19.5) | 82 (82.0) 18 (18.0) | 79 (79.0) 21 (21.0) | 0.592 |

| Q5. Are you open to having the dentist measure your blood glucose level using a finger prick? | ||||

| Yes No | 160 (80.0) 40 (20.0) | 82 (82.0) 18 (18.0) | 78 (78.0) 22 (22.0) | 0.480 |

| Q6. Are you open to having the dentist measure your cholesterol using a finger prick? | ||||

| Yes No | 160 (80.0) 40 (20.0) | 84 (84.0) 16 (16.0) | 76 (76.0) 24 (24.0) | 0.157 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Özcan, A.; Nijland, N.; Gerdes, V.E.A.; Bruers, J.J.M.; Loos, B.G. Willingness for Medical Screening in a Dental Setting—A Pilot Questionnaire Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6969. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20216969

Özcan A, Nijland N, Gerdes VEA, Bruers JJM, Loos BG. Willingness for Medical Screening in a Dental Setting—A Pilot Questionnaire Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(21):6969. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20216969

Chicago/Turabian StyleÖzcan, Asiye, Nina Nijland, Victor E. A. Gerdes, Josef J. M. Bruers, and Bruno G. Loos. 2023. "Willingness for Medical Screening in a Dental Setting—A Pilot Questionnaire Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 21: 6969. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20216969

APA StyleÖzcan, A., Nijland, N., Gerdes, V. E. A., Bruers, J. J. M., & Loos, B. G. (2023). Willingness for Medical Screening in a Dental Setting—A Pilot Questionnaire Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(21), 6969. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20216969