A Diagram of the Social-Ecological Conditions of Opioid Misuse and Overdose

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Review and Diagram Creation

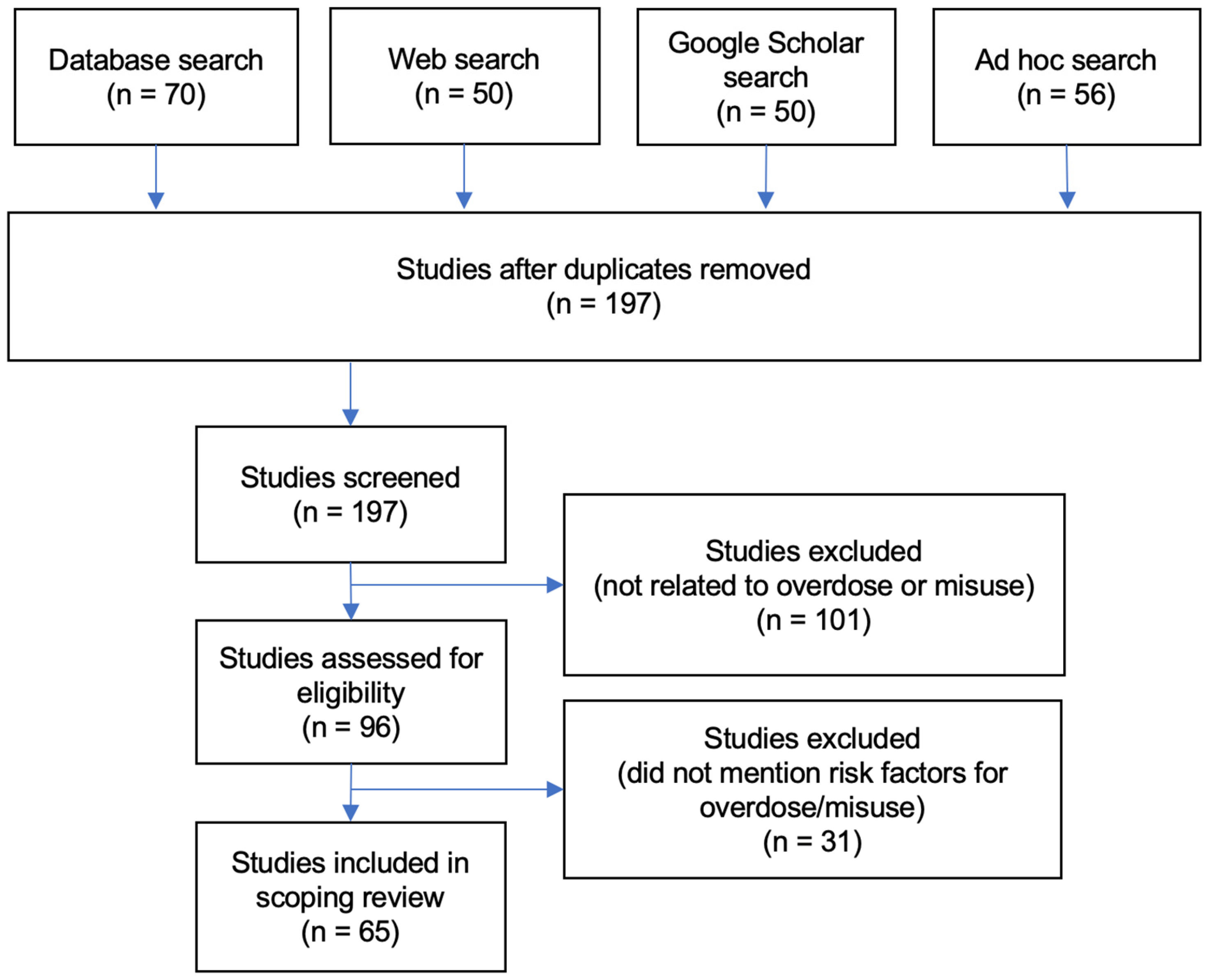

2.1.1. Literature Search Parameters

2.1.2. Literature Sample

2.1.3. Content Analysis

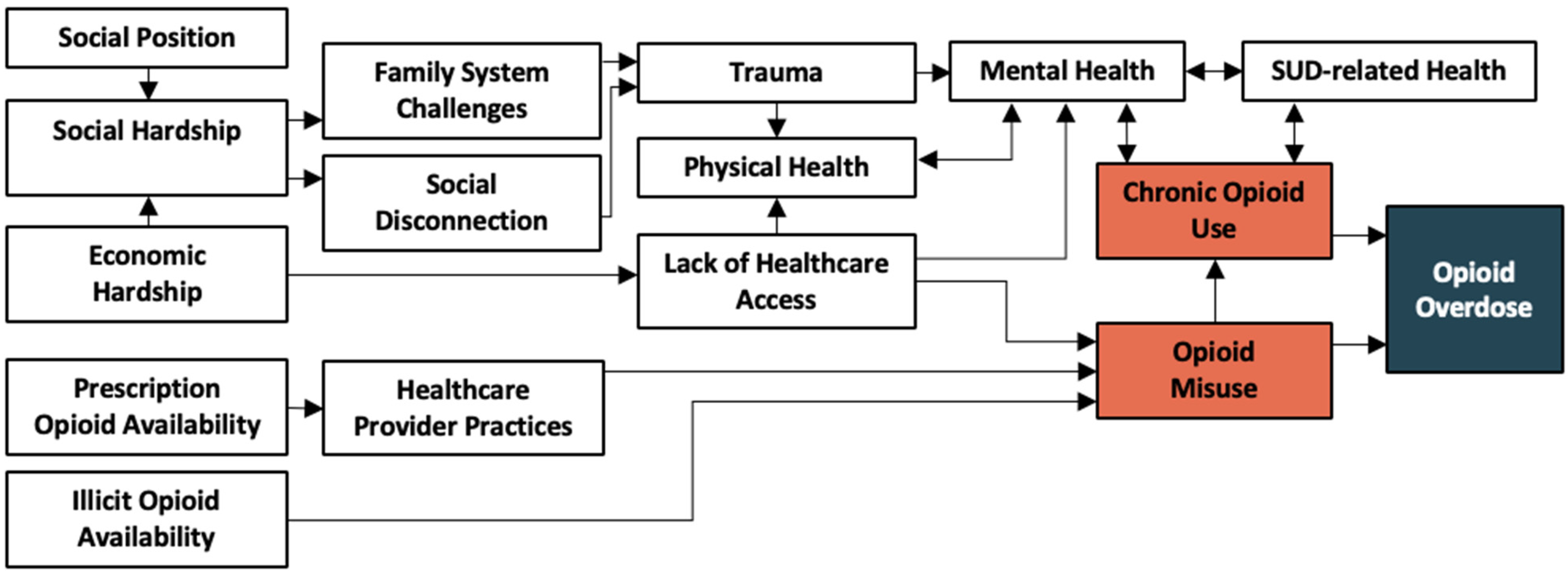

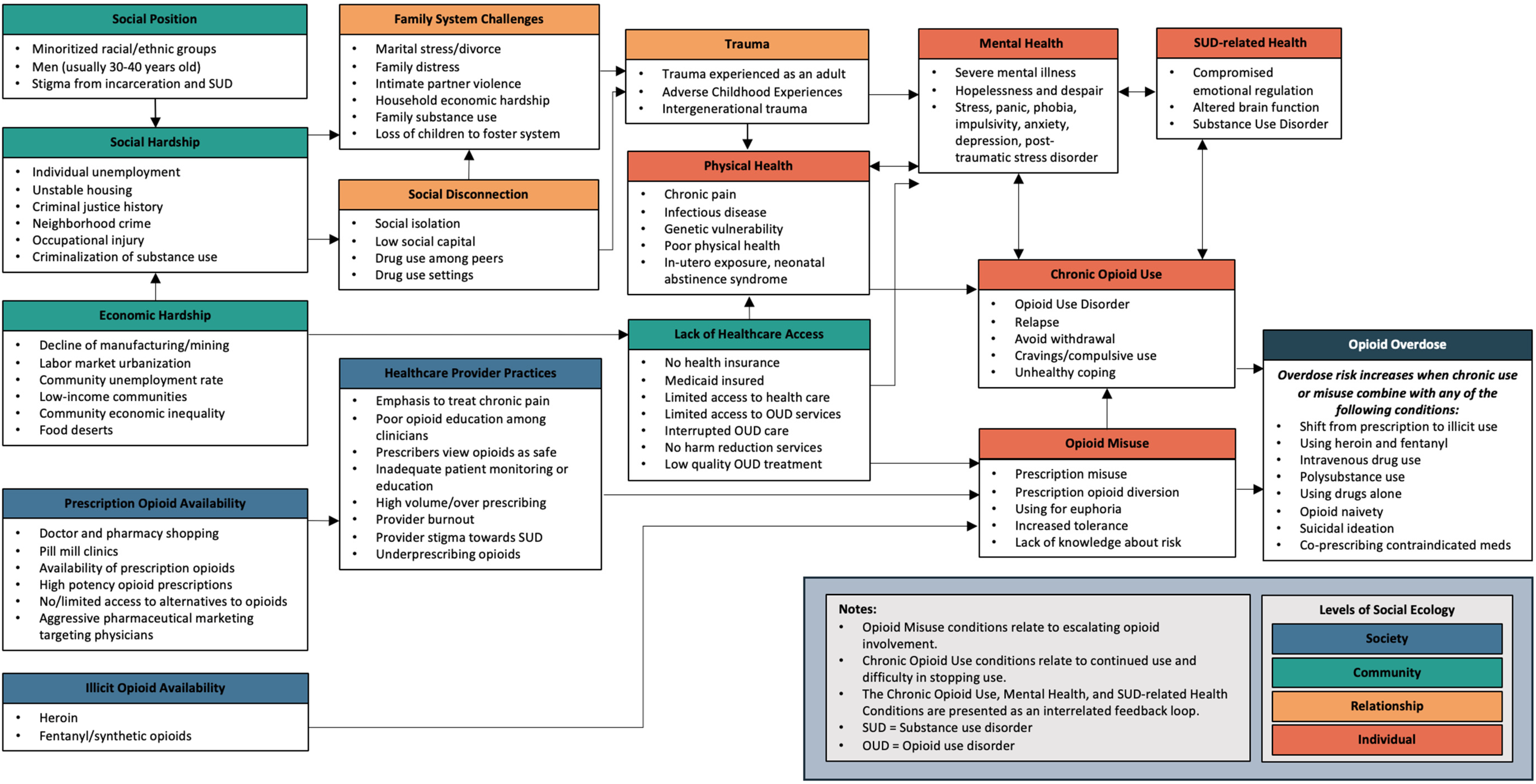

2.1.4. Diagram Construction

2.2. Subject Matter Expert Diagram Review

2.2.1. Interview Sample

2.2.2. Interview Data Collection

2.2.3. Interview Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Conditions and Categories

3.2. Diagram Revisions

3.3. Insight on Intervention Strategies Informed by an Ecological Perspective

I think it’s going to be very hard to make any progress [only focusing] downstream…we can do all this work trying to get people mental health care or trying to get them housed…but if that housing [requires] them being abstinent from substances, we are automatically cutting out wide swathes of the population who are either not ready or don’t have a goal of being abstinent from substances. If we’re trying to address some of these things in isolation from actual policy change, I think we’re going to always be fighting an uphill battle.—Social worker specializing in SUD/OUD

3.4. Insight on Diagram Usefulness and Future Opportunities

If [the diagram] really comes together and simplifies, it could help the general public see these connections, because that’s what you get in your home or on the news or when politicians are talking, you know there’s all kinds of different things that come up. But I don’t think that anyone’s ever seen a document like this that really connects all the dots where they say, ‘Hey…my uncle Jim who died of an opioid overdose and when I look at this document, I can see this is how he started out. He dropped out of college, then he lost his job, then he got divorced, then we found out he had depression,’ you know what I mean? I don’t think that people see all those connections and I think that’s really important for people to understand to really get a better feel for substance use and what it means to have an addiction.—OUD intervention program manager at a local health department

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Courtwright, D.T. Dark Paradise: A History of Opiate Addiction in America; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2001; ISBN 978-0-674-00585-3. [Google Scholar]

- Ciccarone, D. The Triple Wave Epidemic: Supply and Demand Drivers of the US Opioid Overdose Crisis. Int. J. Drug Policy 2019, 71, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, T.D.; Kerridge, B.T.; Goldstein, R.B.; Chou, S.P.; Zhang, H.; Jung, J.; Pickering, R.P.; Ruan, W.J.; Smith, S.M.; Huang, B.; et al. Nonmedical Prescription Opioid Use and DSM-5 Nonmedical Prescription Opioid Use Disorder in the United States. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2016, 77, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco, C.; Alderson, D.; Ogburn, E.; Grant, B.F.; Nunes, E.V.; Hatzenbuehler, M.L.; Hasin, D.S. Changes in the Prevalence of Non-Medical Prescription Drug Use and Drug Use Disorders in the United States: 1991–1992 and 2001–2002. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007, 90, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse Drug Overdose Death Rates. Available online: https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates# (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- Rose, M.E. Are Prescription Opioids Driving the Opioid Crisis? Assumptions vs. Facts. Pain Med. 2018, 19, 793–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, N.; Beletsky, L.; Ciccarone, D. Opioid Crisis: No Easy Fix to Its Social and Economic Determinants. Am. J. Public Health 2018, 108, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Library of Medicine PubMed. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Altekruse, S.F.; Cosgrove, C.M.; Altekruse, W.C.; Jenkins, R.A.; Blanco, C. Socioeconomic Risk Factors for Fatal Opioid Overdoses in the United States: Findings from the Mortality Disparities in American Communities Study (MDAC). PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0227966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monnat, S.M. Factors Associated with County-Level Differences in U.S. Drug-Related Mortality Rates. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2018, 54, 611–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoorob, M.J.; Salemi, J.L. Bowling Alone, Dying Together: The Role of Social Capital in Mitigating the Drug Overdose Epidemic in the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017, 173, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropsey, K.L.; Martin, S.; Clark, C.B.; McCullumsmith, C.B.; Lane, P.S.; Hardy, S.; Hendricks, P.S.; Redmond, N. Characterization of Opioid Overdose and Response in a High-Risk Community Corrections Sample: A Preliminary Study. J. Opioid Manag. 2013, 9, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mital, S.; Wolff, J.; Carroll, J.J. The Relationship between Incarceration History and Overdose in North America: A Scoping Review of the Evidence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020, 213, 108088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention the Social-Ecological Model: A Framework for Prevention. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/about/social-ecologicalmodel.html (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Jalali, M.S.; Botticelli, M.; Hwang, R.C.; Koh, H.K.; McHugh, R.K. The Opioid Crisis: A Contextual, Social-Ecological Framework. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2020, 18, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renger, R.; Foltysova, J.; Becker, K.L.; Souvannasacd, E. The Power of the Context Map: Designing Realistic Outcome Evaluation Strategies and Other Unanticipated Benefits. Eval. Program Plan. 2015, 52, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renger, R.; Titcomb, A. A Three-Step Approach to Teaching Logic Models. Am. J. Eval. 2002, 23, 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swedberg, R. Can You Visualize Theory? On the Use of Visual Thinking in Theory Pictures, Theorizing Diagrams, and Visual Sketches. Sociol. Theory 2016, 34, 250–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joanna Briggs Institute. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual 2015: Methodology for JBI Scoping Reviews; Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2015; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic Review or Scoping Review? Guidance for Authors When Choosing between a Systematic or Scoping Review Approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping Studies: Advancing the Methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daudt, H.M.; van Mossel, C.; Scott, S.J. Enhancing the Scoping Study Methodology: A Large, Inter-Professional Team’s Experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s Framework. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piasecki, J.; Waligora, M.; Dranseika, V. Google Search as an Additional Source in Systematic Reviews. Sci. Eng. Ethics 2018, 24, 809–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wildemuth, B.M. Qualitative Analysis of Content. In Applications of Social Research Methods to Questions in Information and Library Science; Wildemuth, B.M., Ed.; Libraries Unlimited: Westport, CT, USA, 2009; pp. 308–319. [Google Scholar]

- Brady, B.R.; De La Rosa, J.S.; Nair, U.S.; Leischow, S.J. Electronic Cigarette Policy Recommendations: A Scoping Review. Am. J. Health Behav. 2019, 43, 88–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbour, R.S. Checklists for Improving Rigour in Qualitative Research: A Case of the Tail Wagging the Dog? BMJ 2001, 322, 1115–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weller, S.C.; Romney, A.K. Systematic Data Collection; Qualitative Research Methods; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1988; ISBN 978-1-4129-8606-9. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, J.; MacEntee, M.; Brondani, M. The Use of Subject Matter Experts in Validating an Oral Health-Related Quality of Life Measure in Korean. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2015, 13, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellarosa, C.; Chen, P.Y. The Effectiveness and Practicality of Occupational Stress Management Interventions: A Survey of Subject Matter Expert Opinions. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 1997, 2, 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, W.Y.; Wardian, J.L.; Sosnov, J.A.; Kotwal, R.S.; Butler, F.K.; Stockinger, Z.T.; Shackelford, S.A.; Gurney, J.M.; Spott, M.A.; Finelli, L.N.; et al. Recommended Medical and Non-Medical Factors to Assess Military Preventable Deaths: Subject Matter Experts Provide Valuable Insights. BMJ Mil. Health 2020, 166, e47–e52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benn, J.; Koutantji, M.; Wallace, L.; Spurgeon, P.; Rejman, M.; Healey, A.; Vincent, C. Feedback from Incident Reporting: Information and Action to Improve Patient Safety. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2009, 18, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiss, D.A. A Biopsychosocial Overview of the Opioid Crisis: Considering Nutrition and Gastrointestinal Health. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chisholm-Burns, M.A.; Spivey, C.A.; Sherwin, E.; Wheeler, J.; Hohmeier, K. The Opioid Crisis: Origins, Trends, Policies, and the Roles of Pharmacists. Am. J. Health-Syst. Pharm. 2019, 76, 424–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthew, D.B. Un-Burying the Lead: Public Health Tools Are the Key to Beating the Opioid Epidemic; USC Schaeffer and Center for Health Policy at Brookings: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kaye, A.D.; Jones, M.R.; Kaye, A.M.; Ripoll, J.G.; Galan, V.; Beakley, B.D.; Calixto, F.; Bolden, J.L.; Urman, R.D.; Manchikanti, L. Prescription Opioid Abuse in Chronic Pain: An Updated Review of Opioid Abuse Predictors and Strategies to Curb Opioid Abuse: Part 1. Pain Physician 2017, 20, S93–S109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkerson, R.G.; Kim, H.K.; Windsor, T.A.; Mareiniss, D.P. The Opioid Epidemic in the United States. Emerg. Med. Clin. 2016, 34, e1–e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornili, K. The Opioid Crisis, Suicides, and Related Conditions: Multiple Clustered Syndemics, Not Singular Epidemics. J. Addict. Nurs. 2018, 29, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Association of Counties; Appalachian Regional Commission. Opioids in Appalachia: The Role of Counties in Reversing a Regional Epidemic; National Association of Counties: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Pear, V.A.; Ponicki, W.R.; Gaidus, A.; Keyes, K.M.; Martins, S.S.; Fink, D.S.; Rivera-Aguirre, A.; Gruenewald, P.J.; Cerdá, M. Urban-Rural Variation in the Socioeconomic Determinants of Opioid Overdose. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019, 195, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melton, S.H.; Melton, S.T. Current State of the Problem: Opioid Overdose Rates and Deaths. Curr. Treat. Options Psychiatry 2019, 6, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-P. Factors Associated with Prescription Opioid Misuse in Adults Aged 50 or Older. Nurs. Outlook 2018, 66, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serdarevic, M.; Striley, C.W.; Cottler, L.B. Gender Differences in Prescription Opioid Use. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2017, 30, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cano, M. Prescription Opioid Misuse among U.S. Hispanics. Addict. Behav. 2019, 98, 106021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manchester, J.; Sullivan, R. Exploring Causes of and Responses to the Opioid Epidemic in New England; Federal Reserve Bank of Boston: Boston, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Monnat, S.M. The Contributions of Socioeconomic and Opioid Supply Factors to U.S. Drug Mortality Rates: Urban-Rural and within-Rural Differences. J. Rural. Stud. 2019, 68, 319–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, T.C.; McGowan, S.K.; Yokell, M.A.; Pouget, E.R.; Rich, J.D. HIV Infection and Risk of Overdose: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. AIDS 2012, 26, 403–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barocas, J.A.; Wang, J.; Marshall, B.D.L.; LaRochelle, M.R.; Bettano, A.; Bernson, D.; Beckwith, C.G.; Linas, B.P.; Walley, A.Y. Sociodemographic Factors and Social Determinants Associated with Toxicology Confirmed Polysubstance Opioid-Related Deaths. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019, 200, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haffajee, R.L.; Lin, L.A.; Bohnert, A.S.B.; Goldstick, J.E. Characteristics of US Counties with High Opioid Overdose Mortality and Low Capacity to Deliver Medications for Opioid Use Disorder. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e196373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoicea, N.; Costa, A.; Periel, L.; Uribe, A.; Weaver, T.; Bergese, S.D. Current Perspectives on the Opioid Crisis in the US Healthcare System. Medicine 2019, 98, e15425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigg, K.K.; Monnat, S.M.; Chavez, M.N. Opioid-Related Mortality in Rural America: Geographic Heterogeneity and Intervention Strategies. Int. J. Drug Policy 2018, 57, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rummans, T.A.; Burton, M.C.; Dawson, N.L. How Good Intentions Contributed to Bad Outcomes: The Opioid Crisis. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2018, 93, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cragg, A.; Hau, J.P.; Woo, S.A.; Kitchen, S.A.; Liu, C.; Doyle-Waters, M.M.; Hohl, C.M. Risk Factors for Misuse of Prescribed Opioids: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2019, 74, 634–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, C. Understanding the Role of Despair in America’s Opioid Crisis; Brookings Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Strang, R. Broadening Our Understanding of Canada’s Epidemics of Pharmaceutical and Contaminated Street Drug Opioid-Related Overdoses. Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Can. 2018, 38, 309–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vancouver Coastal Health. Response to the Opioid Overdose Crisis in Vancouver Coastal Health; Vancouver Coastal Health: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Opioid Overdose; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bohnert, A.S.B.; Ilgen, M.A. Understanding Links among Opioid Use, Overdose, and Suicide. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, N.B.; Fraser, V.; Boikos, C.; Richardson, R.; Harper, S. Determinants of Increased Opioid-Related Mortality in the United States and Canada, 1990–2013: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, e32–e42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilokthornsakul, P.; Moore, G.; Campbell, J.D.; Lodge, R.; Traugott, C.; Zerzan, J.; Allen, R.; Page, R.L. Risk Factors of Prescription Opioid Overdose Among Colorado Medicaid Beneficiaries. J. Pain 2016, 17, 436–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmerhorst, G.T.; Teunis, T.; Janssen, S.J.; Ring, D. An Epidemic of the Use, Misuse and Overdose of Opioids and Deaths Due to Overdose, in the United States and Canada: Is Europe Next? Bone Jt. J. 2017, 99, 856–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zedler, B.; Xie, L.; Wang, L.; Joyce, A.; Vick, C.; Kariburyo, F.; Rajan, P.; Baser, O.; Murrelle, L. Risk Factors for Serious Prescription Opioid-Related Toxicity or Overdose among Veterans Health Administration Patients. Pain Med. 2014, 15, 1911–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, B.J.; Liang, Y. Drug Overdose in a Retrospective Cohort with Non-Cancer Pain Treated with Opioids, Antidepressants, and/or Sedative-Hypnotics: Interactions with Mental Health Disorders. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2015, 30, 1081–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bair, M.J.; Bohnert, A.S. Overdoses in Patients on Opioids: Risks Associated with Mental Health Conditions and Their Treatment. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2015, 30, 1051–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohnert, A.S.B.; Valenstein, M.; Bair, M.J.; Ganoczy, D.; McCarthy, J.F.; Ilgen, M.A.; Blow, F.C. Association Between Opioid Prescribing Patterns and Opioid Overdose-Related Deaths. JAMA 2011, 305, 1315–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazan, O. The True Cause of the Opioid Epidemic. Available online: https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2020/01/what-caused-opioid-epidemic/604330/ (accessed on 28 May 2020).

- Wawrzyniak, K.M.; Sabo, A.; McDonald, A.; Trudeau, J.J.; Poulose, M.; Brown, M.; Katz, N.P. Root Cause Analysis of Prescription Opioid Overdoses. J. Opioid Manag. 2015, 11, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.; Nolan, S.; Beaulieu, T.; Shalansky, S.; Ti, L. Inappropriate Opioid Prescribing Practices: A Narrative Review. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2019, 76, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glanz, J.M.; Binswanger, I.A.; Shetterly, S.M.; Narwaney, K.J.; Xu, S. Association between Opioid Dose Variability and Opioid Overdose among Adults Prescribed Long-Term Opioid Therapy. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e192613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grattan, A.; Sullivan, M.D.; Saunders, K.W.; Campbell, C.I.; Von Korff, M.R. Depression and Prescription Opioid Misuse among Chronic Opioid Therapy Recipients with No History of Substance Abuse. Ann. Fam. Med. 2012, 10, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, H. RTI International—Insights; RTI International: Research Triangle Park, NC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hollingsworth, A.; Ruhm, C.J.; Simon, K. Macroeconomic Conditions and Opioid Abuse. J. Health Econ. 2017, 56, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, L.R. Risk Factors for Opioid-Use Disorder and Overdose. Anesth. Analg. 2017, 125, 1741–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, A.; Branscum, A.J.; Li, J.; MacKinnon, N.J.; Hincapie, A.L.; Cuadros, D.F. Epidemiological and Geospatial Profile of the Prescription Opioid Crisis in Ohio, United States. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joudrey, P.J.; Khan, M.R.; Wang, E.A.; Scheidell, J.D.; Edelman, E.J.; McInnes, D.K.; Fox, A.D. A Conceptual Model for Understanding Post-Release Opioid-Related Overdose Risk. Addict. Sci. Clin. Pract. 2019, 14, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino, R.; Bowden, N.; Katamneni, S.; Coustasse, A. The Opioid Epidemic in West Virginia. Health Care Manag. 2019, 38, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olfson, M.; Wall, M.; Wang, S.; Crystal, S.; Blanco, C. Risks of Fatal Opioid Overdose during the First Year Following Nonfatal Overdose. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018, 190, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, E.C.; Dixit, A.; Humphreys, K.; Darnall, B.D.; Baker, L.C.; Mackey, S. Association between Concurrent Use of Prescription Opioids and Benzodiazepines and Overdose: Retrospective Analysis. BMJ 2017, 356, j760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackesy-Amiti, M.E.; Donenberg, G.R.; Ouellet, L.J. Prescription Opioid Misuse and Mental Health among Young Injection Drug Users. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abus. 2015, 41, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merrick, M.T.; Ford, D.C.; Haegerich, T.M.; Simon, T. Adverse Childhood Experiences Increase Risk for Prescription Opioid Misuse. J. Prim. Prev. 2020, 41, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gold, M. Suicide Might Be a Root Cause of More Opioid Overdoses than We Thought. Available online: https://www.addictionpolicy.org/post/suicide-might-be-a-root-cause-of-more-opioid-overdoses-than-we-thought (accessed on 6 July 2023).

- Reynolds, C.J.; Vest, N.; Tragesser, S.L. Borderline Personality Disorder Features and Risk for Prescription Opioid Misuse in a Chronic Pain Sample: Roles for Identity Disturbances and Impulsivity. J. Pers. Disord. 2021, 35, 270–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takemoto, E.; Brackbill, R.; Martins, S.; Farfel, M.; Jacobson, M. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Risk of Prescription Opioid Use, over-Use, and Misuse among World Trade Center Health Registry Enrollees, 2015–2016. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020, 210, 107959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zale, E.L.; Dorfman, M.L.; Hooten, W.M.; Warner, D.O.; Zvolensky, M.J.; Ditre, J.W. Tobacco Smoking, Nicotine Dependence, and Patterns of Prescription Opioid Misuse: Results from a Nationally Representative Sample. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2015, 17, 1096–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miech, R.; Johnston, L.; O’Malley, P.M.; Keyes, K.M.; Heard, K. Prescription Opioids in Adolescence and Future Opioid Misuse. Pediatrics 2015, 136, e1169–e1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tori, M.E.; Larochelle, M.R.; Naimi, T.S. Alcohol or Benzodiazepine Co-Involvement with Opioid Overdose Deaths in the United States, 1999-2017. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e202361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morley, K.I.; Ferris, J.A.; Winstock, A.R.; Lynskey, M.T. Polysubstance Use and Misuse or Abuse of Prescription Opioid Analgesics: A Multi-Level Analysis of International Data. Pain 2017, 158, 1138–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, R.M.; Cary, M.; Duarte, G.; Jesus, G.; Alarcão, J.; Torre, C.; Costa, S.; Costa, J.; Carneiro, A.V. Effectiveness of Needle and Syringe Programmes in People Who Inject Drugs—An Overview of Systematic Reviews. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholes, R.; Reyers, B.; Biggs, R.; Spierenburg, M.; Duriappah, A. Multi-Scale and Cross-Scale Assessments of Social–Ecological Systems and Their Ecosystem Services. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2013, 5, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, T.Y.; Stringfellow, E.J.; Stafford, C.A.; DiGennaro, C.; Homer, J.B.; Wakeland, W.; Eggers, S.L.; Kazemi, R.; Glos, L.; Ewing, E.G.; et al. Modeling the Evolution of the US Opioid Crisis for National Policy Development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2115714119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.; Laderman, M.; Hyatt, J.; Krueger, J. Addressing the Opioid Crisis in the United States. Institute for Healthcare Improvement: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Braveman, P.; Egerter, S.; Williams, D.R. The Social Determinants of Health: Coming of Age. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2011, 32, 381–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braveman, P.; Gottlieb, L. The Social Determinants of Health: It’s Time to Consider the Causes of the Causes. Public Health Rep. 2014, 129, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Room, R. Stigma, Social Inequality and Alcohol and Drug Use. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2005, 24, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMarco, L.M.; Dwyer, R.E.; Haynie, D.L. The Accumulation of Disadvantage: Criminal Justice Contact, Credit, and Debt in the Transition to Adulthood*. Criminology 2021, 59, 545–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volkow, N.D.; Poznyak, V.; Saxena, S.; Gerra, G. Drug Use Disorders: Impact of a Public Health Rather than a Criminal Justice Approach. World Psychiatry 2017, 16, 213–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matusow, H.; Dickman, S.L.; Rich, J.D.; Fong, C.; Dumont, D.M.; Hardin, C.; Marlowe, D.; Rosenblum, A. Medication Assisted Treatment in US Drug Courts: Results from a Nationwide Survey of Availability, Barriers and Attitudes. J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 2013, 44, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloyd, C. The Stigmatization of Problem Drug Users: A Narrative Literature Review. Drugs Educ. Prev. Policy 2013, 20, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIver, J.S. Seeking Solutions to the Opioid Crisis. Pharm. Ther. 2017, 42, 478. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services Overdose Prevention Strategy. Available online: https://www.hhs.gov/overdose-prevention/overdose-prevention-strategy (accessed on 13 July 2023).

- Ritchie, C.S.; Garrett, S.B.; Thompson, N.; Miaskowski, C. Unintended Consequences of Opioid Regulations in Older Adults with Multiple Chronic Conditions. Gerontologist 2020, 60, 1343–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, D.; Alpert, A.; Pacula, R.L. A Transitioning Epidemic: How The Opioid Crisis Is Driving the Rise in Hepatitis C. Health Aff. 2019, 38, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Belle, S.B.; Marchal, B.; Dubourg, D.; Kegels, G. How to Develop a Theory-Driven Evaluation Design? Lessons Learned from an Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health Programme in West Africa. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Silva, M.J.; Breuer, E.; Lee, L.; Asher, L.; Chowdhary, N.; Lund, C.; Patel, V. Theory of Change: A Theory-Driven Approach to Enhance the Medical Research Council’s Framework for Complex Interventions. Trials 2014, 15, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chibanda, D.; Verhey, R.; Munetsi, E.; Cowan, F.M.; Lund, C. Using a Theory Driven Approach to Develop and Evaluate a Complex Mental Health Intervention: The Friendship Bench Project in Zimbabwe. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2016, 10, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.; Bagheri, N.; Salinas-Perez, J.A.; Smurthwaite, K.; Walsh, E.; Furst, M.; Rosenberg, S.; Salvador-Carulla, L. Role of Visual Analytics in Supporting Mental Healthcare Systems Research and Policy: A Systematic Scoping Review. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 50, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, J.K.; Ford, M.A.; Bonnie, R.J. Evidence on Strategies for Addressing the Opioid Epidemic. In Pain Management and the Opioid Epidemic: Balancing Societal and Individual Benefits and Risks of Prescription Opioid Use; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

| Society Level | |

|---|---|

| Categories and Conditions | Condition Descriptions |

| Illicit Opioid Availability | |

| |

| Prescription Opioid Availability | |

| |

| Healthcare Provider Practices | |

|

|

| Community Level | |

| Social Hardship | |

|

|

| Social Position | |

| |

| Economic Hardship | |

|

|

| Lack of Healthcare Access | |

|

|

| Relationship Level | |

| Family System Challenges | |

|

|

| Social Disconnection | |

|

|

| Trauma | |

|

|

| Individual Level | |

| Physical Health | |

|

|

| Mental Health | |

| |

| SUD-related Health | |

| |

| Chronic Opioid Use | |

| |

| Opioid Misuse | |

| |

| Opioid Overdose | |

| Opioid Overdose (overdose risk increases when chronic use or misuse conditions combine with these conditions) | |

| |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brady, B.R.; Taj, E.A.; Cameron, E.; Yoder, A.M.; De La Rosa, J.S. A Diagram of the Social-Ecological Conditions of Opioid Misuse and Overdose. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6950. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20206950

Brady BR, Taj EA, Cameron E, Yoder AM, De La Rosa JS. A Diagram of the Social-Ecological Conditions of Opioid Misuse and Overdose. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(20):6950. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20206950

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrady, Benjamin R., Ehmer A. Taj, Elena Cameron, Aaron M. Yoder, and Jennifer S. De La Rosa. 2023. "A Diagram of the Social-Ecological Conditions of Opioid Misuse and Overdose" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 20: 6950. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20206950

APA StyleBrady, B. R., Taj, E. A., Cameron, E., Yoder, A. M., & De La Rosa, J. S. (2023). A Diagram of the Social-Ecological Conditions of Opioid Misuse and Overdose. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(20), 6950. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20206950