Assessing Medical Students’ Preferences for Rural Internships Using a Discrete Choice Experiment: A Case Study of Medical Students in a Public University in the Western Cape

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

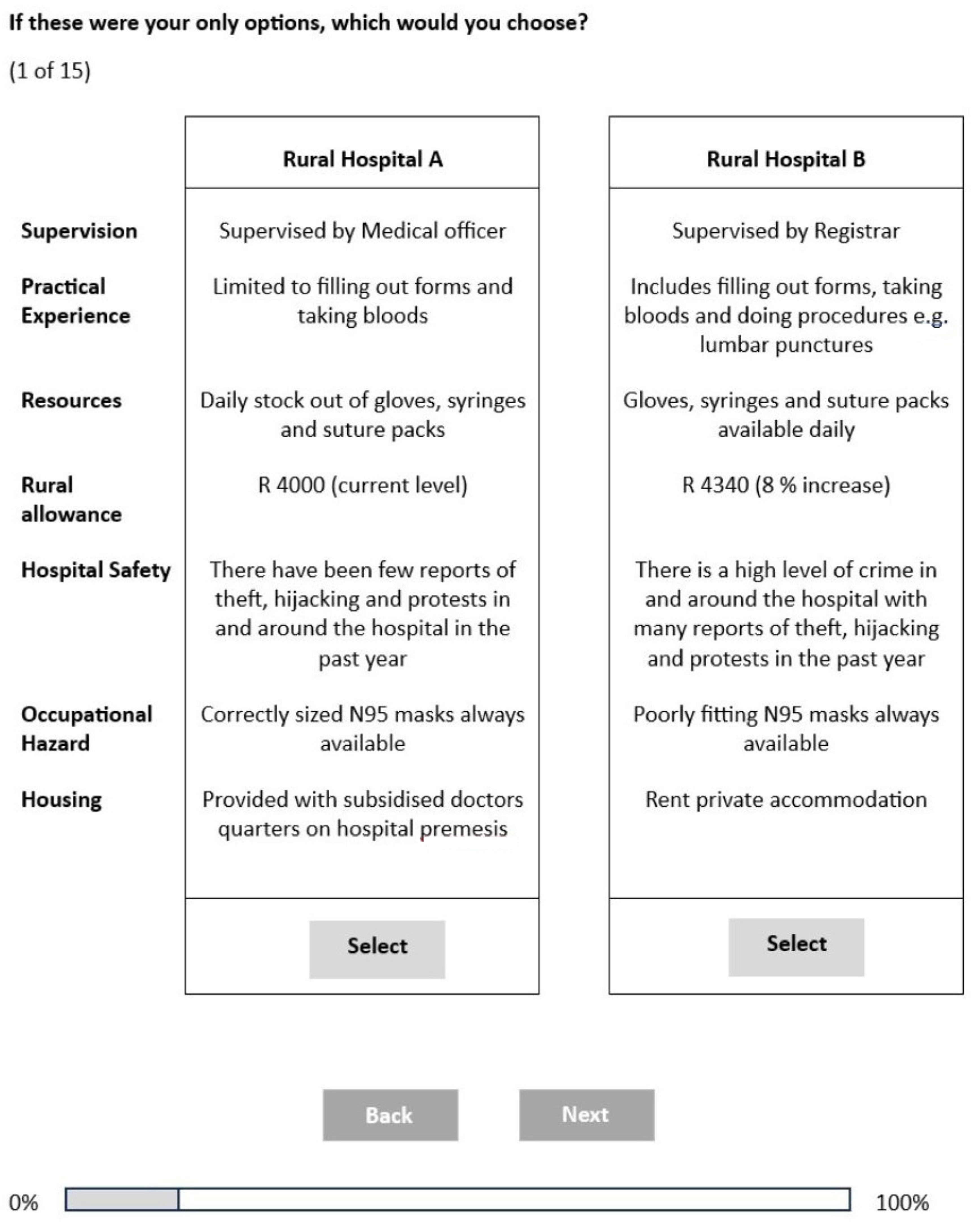

2.2. Discrete Choice Experiment

2.3. Attribute Identification

2.4. Questionnaire Design

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Ethical Approval

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

3.2. Main Effects Only

3.3. Sub-Group Analysis

3.4. Willingness to Pay

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Campbell, J.; Dussault, G.; Buchan, J.; Pozo-Martin, F.; Guerra Arias, M.; Leone, C.; Siyam, A.; Cometto, G. A Universal Truth: No Health without a Workforce; Forum Report: Third Global Forum on Human Resources for Health; Global Health Workforce Alliance and World Health Organization: Recife, Brazil, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Everybody’s Business: Strengthening Health Systems to Improve Health Outcomes: WHO’s Framework for Action; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy on Human Resources for Health: Workforce 2030; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Increasing Access to Health Workers in Remote and Rural Areas through Improved Retention; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, H.; Blaauw, D.; Gilson, L.; Chabikuli, N.; Goudge, J. Health systems and access to antiretroviral drugs for HIV in Southern Africa: Service delivery and human resources challenges. Reprod. Health Matters 2006, 14, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagarde, M.; Blaauw, D. Pro-social preferences and self-selection into jobs: Evidence from South African nurses. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2014, 107, 136–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dambisya, Y.M. A Review of Non-Financial Incentives for Health Worker Retention in East and Southern Africa; Equinet Discussion Paper; Training and Research Support Centre: Harare, Zimbabwe, 2007; (Internet); Available online: https://equinetafrica.org/sites/default/files/uploads/documents/DIS44HRdambisya.pdf (accessed on 6 July 2020).

- George, G.; Quinlan, T.; Reardon, C.; Aguilera, J.F. Where are we short and who are we short of? A review of the human resources for health in South Africa. Health SA Gesondheid 2012, 17, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Health Observatory Data Repository; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bateman, C. Slim pickings as 2008 health staff crisis looms. S. Afr. Med. J. 2007, 97, 1032. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Rural Population (% of Total Population)—South Africa (Internet). Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.RUR.TOTL.ZS?locations=ZA (accessed on 6 July 2020).

- van Rensburg, H.C. South Africa’s protracted struggle for equal distribution and equitable access–still not there. Hum. Resour. Health 2014, 12, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid, S. Community service for health professionals: Human resources. S. Afr. Health Rev. 2002, 1, 135–160. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health, South Africa. Human Resources for Health South Africa: HRH Strategy for the Health Sector 2012/13–2016/17; National Department of Health South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2011; (Internet). Available online: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/hrhstrategy0.pdf (accessed on 6 July 2020).

- Boydstun, J.; Cossman, J.S. Career expectancy of physicians active in patient care: Evidence from Mississippi. Rural. Remote Health 2016, 16, 3813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mofolo, N.; Botes, J. South African Family Practice An evaluation of factors influencing perceptual experiences and future plans of final-year medical interns in the Free State. S. Afr. Fam. Pract. 2013, 58, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Longmore, B.; Ronnie, L. Human resource management practices in a medical complex in the Eastern Cape, South Africa: Assessing their impact on the retention of doctors. S. Afr. Med. J. 2014, 104, 368–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosgrave, C.; Malatzky, C.; Gillespie, J. Social determinants of rural health workforce retention: A scoping review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockers, P.C.; Jaskiewicz, W.; Wurts, L.; Kruk, M.E.; Mgomella, G.S.; Ntalazi, F.; Tulenko, K. Preferences for working in rural clinics among trainee health professionals in Uganda: A discrete choice experiment. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vujicic, M.; Shengelia, B.; Alfano, M.; Bui, H. Social Science & Medicine Physician shortages in rural Vietnam: Using a labor market approach to inform policy. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 73, 970–977. [Google Scholar]

- De Bekker-Grob, E.W.D.E.; Ryan, M.; Gerard, K. Discrete choice experiments in health economics: A review of the literature. Health Econ. 2012, 21, 145–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, M.; Gerard, K.; Amaya-Amaya, M. Using Discrete Choice Experiments to Value Health and Health Care; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 13–46. [Google Scholar]

- Louviere, J.J.; David, H.A.; Swait, J.D. Stated Choice Methods: Analysis and Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, F.R.; Lancsar, E.; Marshall, D.; Kilambi, V.; Bs, B.A.; Mühlbacher, A.; Regier, D.A.; Bresnahan, B.W.; Kanninen, B.; Bridges, J.F.P. Constructing Experimental Designs for Discrete-Choice Experiments: Report of the ISPOR Conjoint Analysis Experimental Design Good Research Practices Task Force. Value Health 2013, 16, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lancsar, E.; Louviere, J. Conducting discrete choice experiments to inform healthcare decision making: A user’s guide. Pharmacoeconomics 2008, 26, 661–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaskiewicz, W.; Deussom, R.; Wurts, L.; Mgomella, G. Rapid Retention Survey Toolkit: Designing Evidence-Based Incentives for Health Workers; USAID and Capacity Plus: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sissolak, D.; Marais, F.; Mehtar, S. TB infection prevention and control experiences of South African nurses-a phenomenological study. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mburu, G.; George, G. Determining the efficacy of national strategies aimed at addressing the challenges facing health personnel working in rural areas in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2017, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South African Medical Association. Public Service Coordinating Bargaining Council Update on salaries and Conditions of Service in Public Service. 2017. Available online: https://www.samedical.org/cmsuploader/viewArticle/607 (accessed on 17 February 2018).

- Oehlert, G.W. A note on the delta method. Am. Stat. 1992, 46, 27–29. [Google Scholar]

- McFadden, D. Conditional logit analysis of qualitative choice behaviour. In Frontiers in Econometrics; Zarembka, P., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1974; pp. 105–142. [Google Scholar]

- Bech, M.; Kjaer, T.; Lauridsen, J. Does the number of choice sets matter? Results from a web survey applying a discrete choice experiment. Health Econ. 2011, 20, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heunis, C.; Mofolo, N.; Kigozi, G.N. Towards national health insurance: Alignment of strategic human resources in South Africa. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2019, 11, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, J.; Pit, S. Medical students on long-term rural clinical placements and their perceptions of urban and rural internships: A qualitative study. BMC Med. Ed. 2020, 20, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, L.; Gilson, L. ‘We are bitter but we are satisfied’: Nurses as street-level bureaucrats in South Africa. Soc. Sci. Med. 2004, 59, 1251–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Guideline on Health Workforce Development, Attraction, Recruitment and Retention in Rural and Remote Areas; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240024229 (accessed on 1 October 2023).

- Matuka, D.O.; Duba, T.; Ngcobo, Z.; Made, F.; Muleba, L.; Nthoke, T.; Singh, T.S. Occupational risk of airborne mycobacterium tuberculosis exposure: A situational analysis in a three-tier public healthcare system in South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Westhuizen, H.M.; Kotze, K.; Narotam, H.; Von Delft, A.; Willems, B.; Dramowski, A. Knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding TB infection control among health science students in a TB-endemic setting. Int. J. Infect. Control 2015, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Be Safe Paramedical Suppliers. Surgical Mask—N95 (20 Pack). 2019. Available online: https://be-safe.co.za/shop/bio-safety/surgical-mask-n95/ (accessed on 6 March 2019).

- World Health Organization. Shortage of Personal Protective Equipment Endangering Health Workers Worldwide. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/03-03-2020-shortage-of-personal-protective-equipment-endangering-health-workers-worldwide (accessed on 24 July 2020).

- Garcia, R.; Spiegel, J.M.; Yassi, A.; Ehrlich, R.; Romão, P.; Nunes, E.A.; Zungu, M.; Mabhele, S. Preventing occupational tuberculosis in health workers: An analysis of state responsibilities and worker rights in Mozambique. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020, 17, 7546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotzee, T.J.; Couper, I.D. What interventions do South African qualified doctors think will retain them in rural hospitals of the Limpopo province of South Africa? Rural. Remote Health 2006, 6, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohta, R.; Sano, C. Reflection in rural family medicine education. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, P.; Lizarondo, L.; Argus, G.; Kumar, S.; Kondalsamy-Chennakesavan, S. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Clinical Supervision of Healthcare students in rural settings: A qualitative study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruk, M.E.; Johnson, J.C.; Gyakobo, M.; Agyei-Baffour, P.; Asabir, K.; Kotha, S.R.; Kwansah, J.; Nakua, E.; Snow, R.C.; Dzodzomenyo, M. Rural practice preferences among medical students in Ghana: A discrete choice experiment. Bull. World Health Organ. 2010, 88, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolstad, J.R. How to make rural jobs more attractive to health workers. Findings from a discrete choice experiment in Tanzania. Health Econ. 2011, 20, 196–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ageyi-baffour, P.; Rominski, S.; Nakua, E.; Gyakobo, M.; Lori, J.R. Factors that influence midwifery students in Ghana when deciding where to practice: A discrete choice experiment. BMC Med. Ed. 2013, 13, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bocoum, F.Y.; Koné, E.; Kouanda, S.; Yaméogo, W.M.E.; Bado, A.R. Which incentive package will retain regionalized health personnel in Burkina Faso: A discrete choice experiment. Hum. Resour. Health 2014, 12 (Suppl. S1), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honda, A.; Vio, F. Incentives for non-physician health professionals to work in the rural and remote areas of Mozambique—A discrete choice experiment for eliciting job preferences. Hum. Resour. Health 2015, 13, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McPake, B.; Scott, A.; Edoka, I. Analyzing Markets for Health Workers: Insights from Labor and Health Economics; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chomitz, K.; Setiadi, G.; Azwar, A.; Ismail, N. What Do Doctors Want? Developing Incentives for Doctors to Serve in Indonesia’s Rural and Remote Areas; Policy Research Working Paper; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Stagg, P.; Greenhill, J.; Worley, P.S. A new model to understand the career choice and practice location decisions of medical graduates. Rural. Remote Health 2009, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Koussa, M.; Atun, R.; Bowser, D.; Kruk, M.E. Factors influencing physicians’ choice of workplace: Systematic review of drivers of attrition and policy interventions to address them. J. Glob. Health 2016, 6, 020403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGrail, M.R.; O’Sullivan, B.G.; Russell, D.J.; Rahman, M. Exploring preference for, and uptake of, rural medical internships, a key issue for supporting rural training pathways. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujicic, M.; Alfano, M.; Ryan, M.; Wesseh, C.S.; Brown-Annan, J. Policy Options to Attract Nurses to Rural Liberia: Evidence from a Discrete Choice Experiment; Health, Nutrition and Population (HNP) discussion paper; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Seaman, C.E.; Green, E.; Freire, K. Effect of rural clinical placements on intention to practice and employment in rural Australia: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGrail, M.R.; Nasir, B.F.; Chater, A.B.; Sangelaji, B.; Kondalsamy-Chennakesavan, S. The value of extended short-term medical training placements in smaller rural and remote locations on future work location: A cohort study. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e068704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrail, M.R.; Chhabra, J.; Hays, R. Evaluation of rural general practice experiences for pre-vocational medical graduates. Rural. Remote Health 2023, 23, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, C.J.; Stevens, C.K. The relationship between early recruitment-related activities and the application decisions of new labor-market entrants: A brand equity approach to recruitment. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Merwe, L.J.; Van Zyl, G.J.; Gibson, A.S.; Viljoen, A.; Iputo, J.E.; Mammen, M.; Chitha, W.; Perez, A.M.; Hartman, N.; Fonn, S.; et al. South African medical schools: Current state of selection criteria and medical students’ demographic profile. S. Afr. Med. J. 2016, 106, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robyn, P.J.; Shroff, Z.; Zang, O.R.; Kingue, S.; Djienouassi, S.; Kouontchou, C.; Sorgho, G. Addressing health workforce distribution concerns: A discrete choice experiment to develop rural retention strategies in Cameroon. Int. J. Health Policy 2015, 4, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Job Attribute | Level | Variable Name |

|---|---|---|

| Supervision | Supervised by Medical Officer [Reference] Supervised by Registrar Supervised by Consultant | -- sup_regist sup_consul |

| Rural Allowance | ZAR 4000 per month [Reference] ZAR 4340 per month (8% increase) ZAR 4800 per month (20% increase) | allowance |

| Accommodation | Rent private accommodation [Reference] Provided with subsidised doctors’ quarters on hospital premises | -- house_provided |

| Resources | Daily stock out of gloves, syringes, and suture packs [Reference] Gloves, syringes, and suture packs are available daily | -- reso_avail |

| Practical Experience | Limited to filling out forms and taking blood [Reference] Includes filling out forms, taking blood, and performing procedures, e.g., lumbar punctures | -- exp_proced |

| Hospital Safety | There is a high level of crime in and around the hospital with many reports of theft, hijacking, and protests in the past year [Reference] There have been few reports of theft, hijacking, and protests in and around the hospital in the past year | -- safety_good |

| Occupational Hazard | No N95 masks available in the hospital [Reference] Poorly fitting N95 masks always available Correctly sized N95 masks always available | -- mask_poor mask_correct |

| Demographic Characteristics | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Completed years | 23.7 (mean) |

| Gender | Male | 63 (31.63) |

| Female | 130 (66.33) | |

| Non-conforming | 4 (2.04) | |

| Province of origin | Western Cape | 72 (36.73) |

| Gauteng | 47 (23.98) | |

| North West | 3 (1.53) | |

| Eastern Cape | 19 (9.69) | |

| Kwa-Zulu Natal | 38 (19.39) | |

| Mpumalanga | 7 (3.57) | |

| Limpopo | 7 (3.57) | |

| Northern Cape | 3 (1.53) | |

| Area of origin | Rural (village/farm) | 14 (7.14) |

| Informal settlement (informal structures around town/city) | 6 (3.06) | |

| Urban (formal structure in suburb/township) | 176 (89.80) | |

| Marital status | Single | 183 (93.37) |

| Married | 13 (6.63) | |

| Child dependents | Yes | 3 (1.53) |

| No | 193 (98.47) | |

| Undergraduate exposure to rural medicine | Yes | 110 (56.12) |

| No | 86 (43.88) | |

| Rural medicine exposure type | Rural facility placement | 8 (5.97) |

| An elective at a rural facility | 43 (32.09) | |

| Student society organised rural medicine exposure | 32 (23.88) | |

| Other | 51 (38.06) | |

| Provincial bursary holder | Yes | 45 (22.96) |

| No | 151 (77.04) | |

| Cuban-trained student | Yes | 7 (3.57) |

| No | 189 (96.43) | |

| Intention to intern | Yes | 192 (97.96) |

| No | 4 (2.04) | |

| Career intention | General Practice | 9 (4.59) |

| Specialisation | 109 (55.61) | |

| I don’t know/undecided | 70 (35.71) | |

| Other | 4 (2.04) | |

| Did not intend to complete internship | 4 (2.04) |

| Attribute | Model 1 Mixed Logit Model | Model 2.1 Females | Model 2.2 Males | Model 2.3 Specialise | Model 2.4 Not Specialise | Model 2.5 Undergraduate Rural Medicine Exposure | Model 2.6 No Undergraduate Rural Medicine Exposure | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (SE) | SD (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | |

| Supervision Registrar | 0.027 (0.060) | 0.385 *** (0.072) | −0.058 (0.085) | 0.066 (0.075) | 0.001 (0.081) | 0.035 (0.127) | 0.053 (0.093) | 0.111 (0.099) |

| Supervision Consultant | 0.135 * (0.069) | 0.323 *** (0.077) | 0.137 (0.091) | 0.145 * (0.083) | 0.254 *** (0.085) | 0.128 (0.147) | 0.232 *** (0.083) | 0.069 (0.124) |

| (Ref: supervision-medical officer) | ||||||||

| Rural Allowance | 0.001 *** (0.000) | −0.001 *** (0.000) | 0.001 *** (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.001 *** (0.000) | 0.001 *** (0.000) | 0.001 *** (0.000) | 0.001 * (0.000) |

| Housing Provided | 0.081 * (0.043) | 0.346 *** (0.071) | 0.112 * (0.058) | 0.029 (0.056) | 0.115 * (0.062) | 0.119 (0.087) | 0.031 (0.058) | 0.205 *** (0.067) |

| (Ref: private housing) | ||||||||

| Basic resources available | 0.621 *** (0.072) | 0.598 *** (0.080) | 0.765 *** (0.105) | 0.408 *** (0.088) | 0.554 *** (0.085) | 1.128 *** (0.190) | 0.542 *** (0.087) | 0.788 *** (0.118) |

| (Ref: basic resources not available) | ||||||||

| Advanced Practical Experience | 0.919 *** (0.083) | 0.828 *** (0.094) | 1.090 *** (0.140) | 0.692 *** (0.116) | 1.154 *** (0.150) | 1.160 *** (0.219) | 1.020 *** (0.153) | 1.050 *** (0.152) |

| (Ref: limited practical experience) | ||||||||

| Hospital Safe | 0.770 *** (0.102) | 0.777 *** (0.100) | 1.968 *** (0.222) | 0.701 *** (0.089) | 1.151 *** (0.173) | 2.462 *** (0.416) | 1.842 *** (0.279) | 1.256 *** (0.370) |

| (Ref: hospital unsafe) | ||||||||

| Poorly fitting N95 mask | −0.059 (0.055) | −0.263 *** (0.100) | −0.139 * (0.078) | 0.044 (0.070) | −0.022 (0.078) | −0.087 (0.125) | −0.048 (0.075) | −0.069 (0.099) |

| Correctly fitting N95 mask | 0.718 *** (0.082) | −0.456 *** (0.087) | 0.832 *** (0.122) | 0.294 *** (0.083) | 0.802 *** (0.109) | 0.875 *** (0.207) | 0.703 *** (0.100) | 0.858 *** (0.158) |

| (Ref: No face mask) | ||||||||

| No. of Observations | 5790 | 1890 | 3900 | 3270 | 2520 | 3300 | 2490 | |

| Log Likelihood | −1338.69 | −1523.99 | −1742.70 | −1627.42 | −1737.65 | −1610.90 | −1714.84 | |

| Wald chi-squared | 200.34 | 126.12 | 108.53 | 97.08 | 58.60 | 102.61 | 102.22 | |

| Prob > chi-square | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | |

| Attribute | WTP ZAR Relative to Base (95% CI) | % of Current Rural Allowance |

|---|---|---|

| Supervision by registrar | 271.45 (−73.79; 616.68) | 6.78 |

| Supervision by consultant | 427.57 (69.51; 785.63) | 10.70 |

| Provision of housing | 233.61 (−22.19; 489.41) | 5.83 |

| Daily availability of basic resources | 1787.13 (915.82; 2658.44) | 44.68 |

| Advanced practical experience | 2645.92 (1345.90; 3945.94) | 66.15 |

| Limited physical threats in and around the facility | 2214.92 (1194.74; 3235.11) | 55.38 |

| Poorly fitting N95 mask | 862.93 (361.32; 1364.54) | 21.58 |

| Correctly fitting N95 mask | 1980.57 (1074.00; 2887.14) | 49.53 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jose, M.; Obse, A.; Zuidgeest, M.; Alaba, O. Assessing Medical Students’ Preferences for Rural Internships Using a Discrete Choice Experiment: A Case Study of Medical Students in a Public University in the Western Cape. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6913. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20206913

Jose M, Obse A, Zuidgeest M, Alaba O. Assessing Medical Students’ Preferences for Rural Internships Using a Discrete Choice Experiment: A Case Study of Medical Students in a Public University in the Western Cape. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(20):6913. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20206913

Chicago/Turabian StyleJose, Maria, Amarech Obse, Mark Zuidgeest, and Olufunke Alaba. 2023. "Assessing Medical Students’ Preferences for Rural Internships Using a Discrete Choice Experiment: A Case Study of Medical Students in a Public University in the Western Cape" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 20: 6913. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20206913

APA StyleJose, M., Obse, A., Zuidgeest, M., & Alaba, O. (2023). Assessing Medical Students’ Preferences for Rural Internships Using a Discrete Choice Experiment: A Case Study of Medical Students in a Public University in the Western Cape. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(20), 6913. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20206913