Primary and Community Care Transformation in Post-COVID Era: Nationwide General Practitioner Survey

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Statistical Analysis

2.2. Ethical Aspects

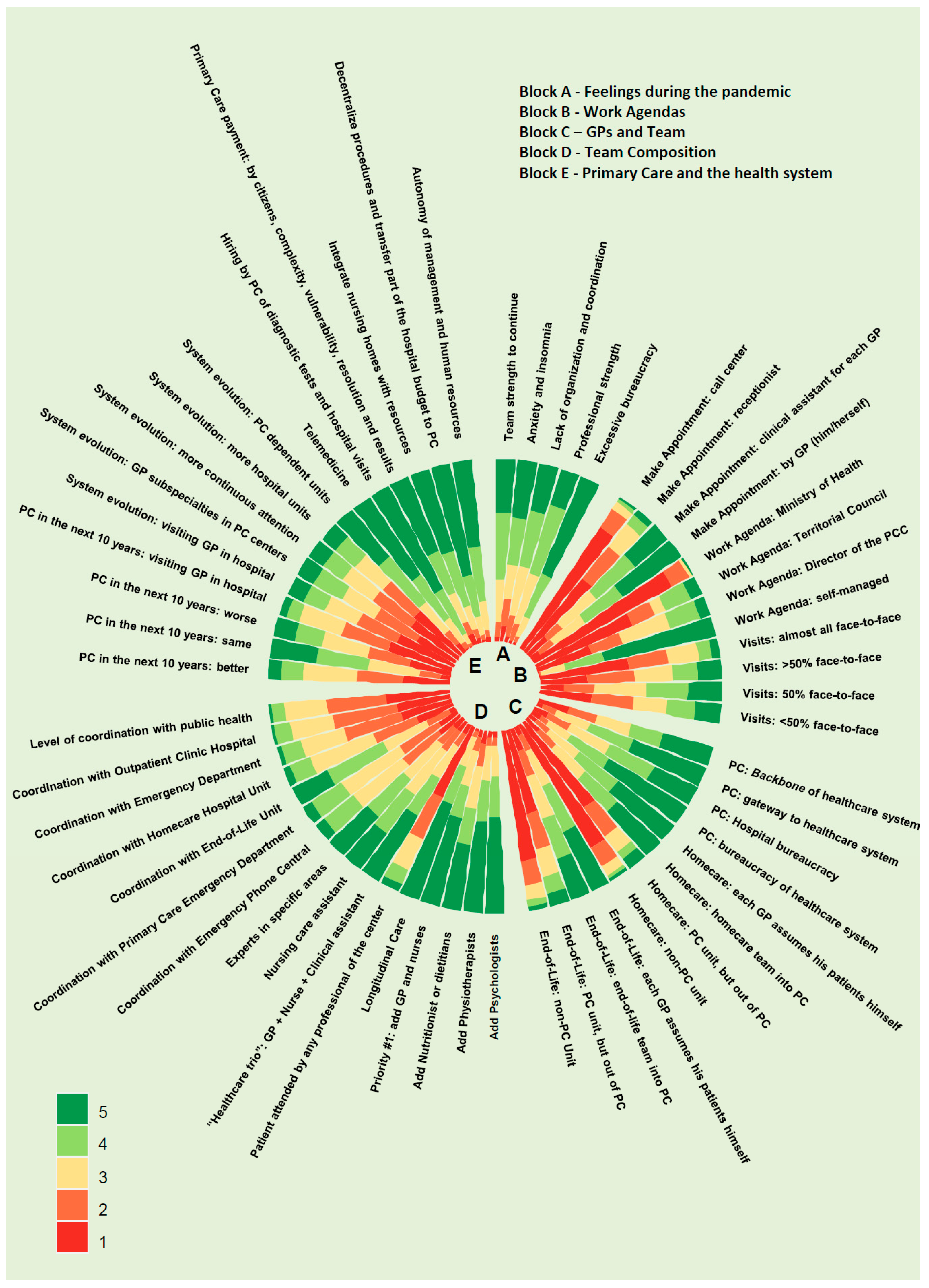

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Block 1-Feelings during the Pandemic | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 1-The work team has shown me all the necessary strength to move forward | 2.2% | 8.3% | 23.2% | 37% | 29.3% |

| 2-I have suffered anguish and/or sleep problems | 8.7% | 14.7% | 18.8% | 26.3% | 31.5% |

| 3-I have felt a lack of organization and coordination | 3.5% | 11.9% | 27.1% | 31% | 26.5% |

| 4-I have felt professionally strong despite adversity | 2% | 9.3% | 28.8% | 39.2% | 20.6% |

| 5-I felt that I wasted my time on sick leave and other bureaucratic tasks | 1.7% | 3.4% | 11.6% | 25.4% | 57.8% |

| Block 2-Work Agenda | |||||

| 6-Who should make face-to-face appointments for patients? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 6.1. Call center | 79.8% | 12% | 4.3% | 2% | 1.6% |

| 6.2. PHC center administrative staff | 51.4% | 22.5% | 15.8% | 6.7% | 3.3% |

| 6.3. A center administrator in coordination with GPs | 13.5% | 10.2% | 24.9% | 27.7% | 23.5% |

| 6.4. Each GP schedules visits after telephone contact | 5.3% | 9.7% | 20.8% | 25.1% | 39% |

| 7-Who should design the agendas of GPs? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 7.1. The Department of Health | 86.3% | 10.9% | 1.5% | 0% | 0.5% |

| 7.2. PHC management | 72.4% | 17% | 7.8% | 19% | 8.5% |

| 7.3. PHC center management | 30.9% | 18% | 27.4% | 17.6% | 5.8% |

| 7.4. Each doctor in agreement with the PHC center management | 0.8% | 0.5% | 13.6% | 22% | 62.8% |

| 8-What proportion of face-to-face versus non-face-to-face visits do you think the work agenda of a GP should have? | |||||

| 8.1. Almost all visits should be face-to-face | 49.6% | 21.7% | 16.7% | 7.5% | 4.2% |

| 8.2. More than 50% face-to-face | 26.1% | 26.2% | 20.6% | 13.9% | 12.9% |

| 8.3. About 50% face-to-face | 13.1% | 16.6% | 28.6% | 22.8% | 18.7% |

| 8.4. Less than 50% face-to-face | 28.5% | 23.2% | 18.3% | 15.6% | 14.1% |

| Block 3-MFiC and PHC Centers | |||||

| 9-What role do you feel general practitioners are taking on in PHC? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 9.1. The backbone | 17.5% | 16.1% | 19.4% | 18.4% | 28.4% |

| 9.2. The gateway of the system | 3.5% | 8.4% | 19.6% | 25.2% | 43.2% |

| 9.3. Administrative tasks of hospital care | 7.8% | 13.9% | 24.5% | 27.1% | 26.5% |

| 9.4. Bureaucratic tasks of the entire health system | 5.2% | 5.3% | 14.5% | 24.3% | 50.5% |

| 10-With respect to home care: | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 10.1. It is the responsibility of each GP and PHC centers by extension | 4.5% | 9% | 20.1% | 26.9% | 39.2% |

| 10.2. Home care and residence teams are required in each PHC center | 9.3% | 12.1% | 22% | 24.1% | 32.2% |

| 10.3. Should be covered by PHC unit external to PHC centers | 58.1% | 19.4% | 10.7% | 5.1% | 6.5% |

| 10.4. It should be managed by a territorial unit external to PHC | 78.7% | 11.2% | 5.8% | 1.9% | 2.1% |

| 11-Regarding end-of-life care: | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 11.1. It is the responsibility of each GP and PHC centers by extension | 5.3% | 9.1% | 21.7% | 27.4% | 36.2% |

| 11.2. Specific equipment is required in each PHC center | 13.2% | 14.6% | 24.8% | 23.6% | 23.5% |

| 11.3. Should be covered by a PHC unit external to the PHC centers | 47.5% | 20.1% | 15.5% | 9.6% | 7.1% |

| 11.4. It should be managed by a non-PHC unit | 72.4% | 13.5% | 8% | 3.6% | 2.5% |

| Block 4-PHC Centers and Their Composition | |||||

| 12-Regarding the composition of PHC centers: | |||||

| 12.1. Psychologists should be added to PHC centers | 3.1% | 4.8% | 16.6% | 22.8% | 52.5% |

| 12.2. Physiotherapists should be added | 3.2% | 4.8% | 19% | 22.7% | 50.1% |

| 12.3. Nutritionists should be added | 7.4% | 12.6% | 23.5% | 20% | 36.3% |

| 12.4. First, the basic structure should be strengthened, and then other professionals should be added | 4.5% | 7.7% | 19.3% | 18.3% | 50% |

| 13-Regarding the organization of PHC centers: | |||||

| 13.1. Continuity of care should be maintained: patient + doctor + nurse | 1.9% | 3.4% | 17% | 22% | 55.5% |

| 13.2. It is necessary to evolve to a model without specific health references, if not attended by a PHC center | 43% | 25.2% | 18.7% | 8.5% | 4.4% |

| 13.3. It is necessary to expand the usual health references (doctor + nurse) by adding a health administrator | 5.8% | 8% | 20.1% | 24.3% | 41.4% |

| 13.4. The TCAI must be developed in direct care | 6.3% | 13% | 30.1% | 26.2% | 24.1% |

| 13.5. We need a mixed model, a reference team + experts within PHC centers | 6.7% | 11.7% | 25.7% | 27.3% | 28.6% |

| 14-How do you currently perceive coordination with other services? (1: very bad, to 5: optimal): | |||||

| 14.1. 061 (emergency telephone) | 14.5% | 25% | 33.4% | 21.1% | 5.8% |

| 14.2. Continuous PHC urgent care (ACUT) | 12% | 25.4% | 37.2% | 19.7% | 5.6% |

| 14.3. End-of-life home care (PADES) | 3.4% | 14.3% | 26.4% | 34.2% | 21.5% |

| 14.4. Home hospitalization | 21.2% | 26% | 37% | 12% | 3.7% |

| 14.5. Hospital emergencies | 28.5% | 33% | 24.5% | 11.1% | 2.7% |

| 14.6. Hospital outpatient consultations | 30% | 36% | 23.7% | 8.9% | 1.4% |

| 14.7. Public health | 35.5% | 32.7% | 23% | 7.2% | 1.5% |

| Block 5-PHC and the Health System | |||||

| 15-If you make a projection of the current health system 10 years from now, how do you see PHC and GPs? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 15.1. Better than now | 25.6% | 25.6% | 29.2% | 12.5% | 6.8% |

| 15.2. Surviving, as in recent years | 5.3% | 12% | 29.4% | 29.5% | 26.4% |

| 15.3. A marginal public service for services not covered by private insurance | 23.4% | 23.5% | 25.8% | 15.3% | 11.8% |

| 15.4. GPs incorporated in hospital services | 37.1% | 27% | 24.5% | 7.3% | 4% |

| 16-How should the health system evolve? | |||||

| 16.1. Strengthening hospitals with the integration of GPs | 34% | 24% | 19.4% | 12.4% | 10% |

| 16.2. Generating GP subspecialties in PHC centers | 24.5% | 25.8% | 20.6% | 17.8% | 10.2% |

| 16.3. Expanding continuous care to give immediate attention: | 31.1% | 26% | 20% | 13.6% | 9.2% |

| 16.4. Generating units dependent on the hospital | 33.4% | 23.1% | 19.6% | 14.1% | 9.7% |

| 16.5. Generating PHC-dependent units | 6.2% | 8.8% | 19.7% | 32.1% | 33.2% |

| 17-It is necessary to promote telemedicine and telemonitoring, using all its potential, with all the technological resources of a modern, developed model | 0.9% | 3.8% | 15.6% | 28.3% | 51.5% |

| 18-Mechanisms must be established to enable the contracting by PHC of complementary tests and first hospital visits | 0.7% | 1.6% | 5.9% | 27.6% | 64.2% |

| 19-It is necessary to implement a PHC payment model linked to the number of citizens assigned, weighted by their level of clinical complexity and social vulnerability, capacity of resolution and health outcomes | 6.5% | 7.2% | 17.4% | 24.5% | 44.4% |

| 20-It is necessary to integrate the health teams of residential centers with PHC centers, accompanying them with the necessary resources for efficient care in this area | 3.1% | 5% | 13.5% | 31.5% | 46.8% |

| 21-In terms of cost-effectiveness, procedures (and budget) of hospital care should be decentralized to PHC centers | 1.3% | 2.8% | 10% | 23.4% | 62.5% |

| 22-Progressively provide PHC centers, with or without legal personality, with autonomy in economic management and human resources (respecting acquired rights), with management and models of economic allocation that favor co-responsibility in care and economic results | 2.3% | 3.8% | 15.8% | 30.6% | 47.5% |

References

- Sistema Nacional de Salud—Ministerio de Sanidad. Available online: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/organizacion/sns/home.htm (accessed on 8 December 2022).

- Resultados de la Encuesta a los Directores de los PHC Centers Ante la Pandemia por COVID-19. Available online: http://gestor.camfic.cat/uploads/ITEM_13019_EBLOG_4057.pdf (accessed on 29 March 2022).

- López, F.; Walsh, S.; Solans, O.; Adroher, C.; Ferraro, G.; García-Altés, A.; Vidal-Alaball, J. Teleconsultation Between Patients and Health Care Professionals in the Catalan Primary Care Service: Message Annotation Analysis in a Retrospective Cross-Sectional Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e19149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Choon Huat Koh, G.; Car, J. COVID-19: A remote assessment in primary care. BMJ 2020, 368, m1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skechers, H.; van Weel, C.; van Boven, K.; Akkermans, R.; Bischoff, E.; Hartman, T.O. The COVID-19 Pandemic in Nijmegen, the Netherlands: Changes in Presented Health Problems and Demand for Primary Care. Ann. Fam. Med. 2021, 19, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Declaration of Alma-Ata. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Primary Health Care, Alma-Ata, Kazakhstan, 6–12 September 1978; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Declaration of Astaná. In Proceedings of the Global Conference on Primary Health Care, Astaná, Kazakhstan, 25–26 October 2018; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sandvik, H.; Hetlevik, Ø.; Blinkenberg, J.; Hunskaar, S. Continuity in general practice as a predictor of mortality, acute hospitalization, and use of out-of-hours services: Registry-based observational study in Norway. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2022, 72, e84–e90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- España. La Década Perdida: Mapa de Austeridad del Gasto Sanitario en España del 2009 al 2018. Informe Amnistía Internacional. EUR41500020-32500. 2020. Available online: https://doc.es.amnesty.org/ms-opac/recordmedia/1@000032500/object/43241/raw (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- Garit Rodriguez, I.; Sánchez Fernández, C.; Fernández-Ruiz, S.; Sánchez Bayle, M. La Atención Primaria en las Comunidades Autónomas. Informe AP 2021. Federación de Asociaciones para la Defensa de la Sanidad Pública (FADSP). Available online: https://fadsp.es/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/InformeAP21.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- Simó, J. La “Serpiente” del Gasto de Personal También Existe. Acta Sanitaria. 5 April 2019. Available online: https://www.actasanitaria.com/la-serpiente-del-gasto-de-personal-tambien-existe/ (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- Los Presupuestos Sanitarios de las AACC para 2022. Federación de Asociaciones para la Defensa de la Sanidad Pública (FADSP). Available online: https://fadsp.es/los-presupuestos-sanitarios-de-las-ccaa-para-2022/ (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- Servei Català de la Salut. Informe D’activitat 2019. Departament de Salut, Generalitat de Catalunya. 2020. 88p. Available online: https://scientiasalut.gencat.cat/bitstream/handle/11351/5515/servei_catala_salut_informe_activitat_2019.pdf?sequence=6&isAllowed=y (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- Atenció Primària en L’era Post-COVID. Revolució per a la Transformació. Societat Catalana de Medicina Familiar i Comunitària. 2021. 32p. Available online: http://gestor.camfic.cat/uploads/ITEM_14356_EBLOG_4160.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- Dai, M.; Willard-Grace, R.; Knox, M.; Larson, S.A.; Magill, M.K.; Grumbach, K.; Peterson, L.E. Team Configurations, Efficiency, and Family Physician Burnout. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2020, 33, 368–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, K.; Marchalik, D.; Farley, H.; Dean, S.M.; Lawrence, E.C.; Hamidi, M.S.; Stewart, M.T. Organizational strategies to reduce physician burnout and improve professional fulfillment. Curr. Probl. Pediatr. Adolesc. Health Care 2019, 49, 100664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisó-Almirall, A.; Kostov, B.; Sánchez, E.; Benavent-Àreu, J.; González de Paz, L. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Primary Health Care Disease Incidence Rates: 2017 to 2020. Ann. Fam. Med. 2022, 20, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coma, E.; Mora, N.; Méndez, L.; Benítez, M.; Hermosilla, E.; Fàbregas, M.; Medina, M. Primary care in the time of COVID-19: Monitoring the effect of the pandemic and the lockdown measures on 34 quality of care indicators calculated for 288 primary care practices covering about 6 million people in Catalonia. BMC Fam. Pract. 2020, 21, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pifarré IArolas, H.; Vidal-Alaball, J.; Gil, J.; López, F.; Nicodemo, C.; Saez, M. Missing Diagnoses during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Year in Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezapour, R.; Dorosti, A.A.; Farahbakhsh, M.; Azami-aghdash, S.; Iranzad, I. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on primary health care utilization: An experience from Iran. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortego, G.G.; Ordóñez, A.C.; Martínez, I.P.; Martín Álvarez, R.; Arroyo de la Rosa, A.; Carbajo Martín, L. Un Día en la Consulta de Medicina de Familia Entre las Olas de la Pandemia. Rev. Clin. Med. Fam. 2022, 15, 47–54. Available online: https://scielo.isciii.es/pdf/albacete/v15n1/1699-695X-albacete-15-01-47.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- Varela, J. Five recommendations to increase the value of clinical practice. Med. Clin. 2021, 156, 187–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrales-Nevado, D.E.; Palomo Cobos, L. La importancia de la longitudinalidad, integralidad, coordinación y continuidad de los cuidados domiciliarios efectuados por enfermería. Enferm. Clin. 2014, 24, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melendez, A. Cuidados paliativos y Atención Primaria. ¿Sola, soportada o sustituida? AMF 2014, 10, 241–242. Available online: http://gestor.camfic.cat/uploads/ITEM_5452.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- Basu, S.; Berkowitz, S.A.; Phillips, R.L.; Bitton, A.; Landon, B.E.; Phillips, R.S. Association of Primary Care Physician Supply with Population Mortality in the United States, 2005–2015. JAMA Intern. Med. 2019, 179, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionne, S.; Boerma, K.W.; van der Zee, J.; Groenewegen, P. Europe’s strong primary care systems are linked to better population health but also to higher health spending. Health Aff. 2013, 32, 124225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, W.L.A.; Boerma, W.G.W.; Van den Berg, M.J.; De Maeseneer, J.; De Rosis, S.; Detollenaere, J.; Groenewegen, P.P. Are people’s health care needs better met when primary care is strong? A synthesis of the results of the QUALICOPC study in 34 countries. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2019, 20, e104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroezen, M.; Schäfer, W.; Sermeus, W.; Hansen, J.; Batenburg, R. Healthcare assistants in EU Member States: An overview. Health Policy 2018, 122, 1109–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, B.; Reeve, H.; Ross, S.; Honeyman, M.; Nosa-Ehima, M.; Sahib, B.; Omojomolo, D. Innovative Models of General Practice. The King’s Fund, UK. 2018. Available online: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/2018-06/Innovative_models_GP_Kings_Fund_June_2018.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2022).

- Puig-Junoy, J.; Ortún, V. Cost efficiency in primary care contracting: A stochastic frontier cost function approach. Health Econ. 2004, 13, 1149–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgemans, S.; Urbina-Pérez, O. New legal forms in health services: Evaluation of a Spanish public policy. Health Policy 2022, 126, 802–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solans, O.; Vidal-Alaball, J.; Roig Cabo, P.; Mora, N.; Coma, E.; Bonet Sinó, J.M.; Seguí, F.L. Characteristics of Citizens and Their Use of Teleconsultations in Primary Care in the Catalan Public Health System Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Retrospective Descriptive Cross-sectional Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e28629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balaji, A.; Clever, S.L. Incorporating Medical Students into Primary Care Telehealth Visits: Tutorial. JMIR Med. Educ. 2021, 7, e24300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eberly, L.A.; Kallan, M.J.; Julien, H.M.; Haynes, N.; Khatana, S.A.M.; Nathan, A.S.; Snider, C.; Chokhsi, M.B.A.; Eneanya, N.D.; Takvorian, S.U.; et al. Patient Characteristics Associated with Telemedicine Access for Primary and Specialty Ambulatory Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2031640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Guzman, K.R.; Snoswell, C.L.; Caffery, L.J.; Smith, A.C. Economic evaluations of videoconference and telephone consultations in primary care: A systematic review. J. Telemed. Telecare 2021, 1357633X211043380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, R. Divided We Fall: Getting the Best Out of General Practice. Research Report, Nuffield Trust (5 February 2018). Available online: https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/research/divided-we-fall-getting-the-best-out-of-general-practice (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- Ferran, M.; Alapont, M. Cómo Nos Organizamos: Mejorando la Accesibilidad. Modelos de Gestión de la Demanda en el Día. AMF 2018, 14, 420–426. Available online: https://amf-semfyc.com/es/web/articulo/mejorando-la-accesibilidad-modelos-de-gestion-de-la-demanda-en-el-dia (accessed on 22 June 2022).

| Sex | Female | 773 (73.54%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 25–35 | 126 (11.98%) |

| 36–45 | 268 (25.49%) | |

| 46–55 | 409 (38.91%) | |

| >55 | 248 (23.59%) | |

| Work experience (in years) | <5 | 99 (09.41%) |

| 6–15 | 238 (22.64%) | |

| 16–25 | 396 (37.67%) | |

| >25 | 318 (30.25%) | |

| Area of work | Urban | 698 (66.41%) |

| Semi-urban | 187 (17.79%) | |

| Rural | 155 (17.74%) | |

| Emergency | 11 (01.04%) | |

| Health Region | Barcelona | 57% |

| Lleida | 13% | |

| Central Catalonia | 10% | |

| Tarragona | 9% | |

| Girona | 8% | |

| Teres de l’Ebre | 2% | |

| Alt Pirineu i Aran | 1% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Solanes-Cabús, M.; Paredes, E.; Limón, E.; Basora, J.; Alarcón, I.; Veganzones, I.; Conangla, L.; Casado, N.; Ortega, Y.; Mestres, J.; et al. Primary and Community Care Transformation in Post-COVID Era: Nationwide General Practitioner Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1600. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021600

Solanes-Cabús M, Paredes E, Limón E, Basora J, Alarcón I, Veganzones I, Conangla L, Casado N, Ortega Y, Mestres J, et al. Primary and Community Care Transformation in Post-COVID Era: Nationwide General Practitioner Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(2):1600. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021600

Chicago/Turabian StyleSolanes-Cabús, Mònica, Eugeni Paredes, Esther Limón, Josep Basora, Iris Alarcón, Irene Veganzones, Laura Conangla, Núria Casado, Yolanda Ortega, Jordi Mestres, and et al. 2023. "Primary and Community Care Transformation in Post-COVID Era: Nationwide General Practitioner Survey" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 2: 1600. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021600

APA StyleSolanes-Cabús, M., Paredes, E., Limón, E., Basora, J., Alarcón, I., Veganzones, I., Conangla, L., Casado, N., Ortega, Y., Mestres, J., Acezat, J., Deniel, J., Cabré, J. J., Ruiz, D. S., Sánchez, M., Illa, A., Viñas, I., Montero, J. J., Cantero, F. X., ... Sisó-Almirall, A. (2023). Primary and Community Care Transformation in Post-COVID Era: Nationwide General Practitioner Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 1600. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021600