Quality of Life in Caregivers of Cancer Patients: A Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

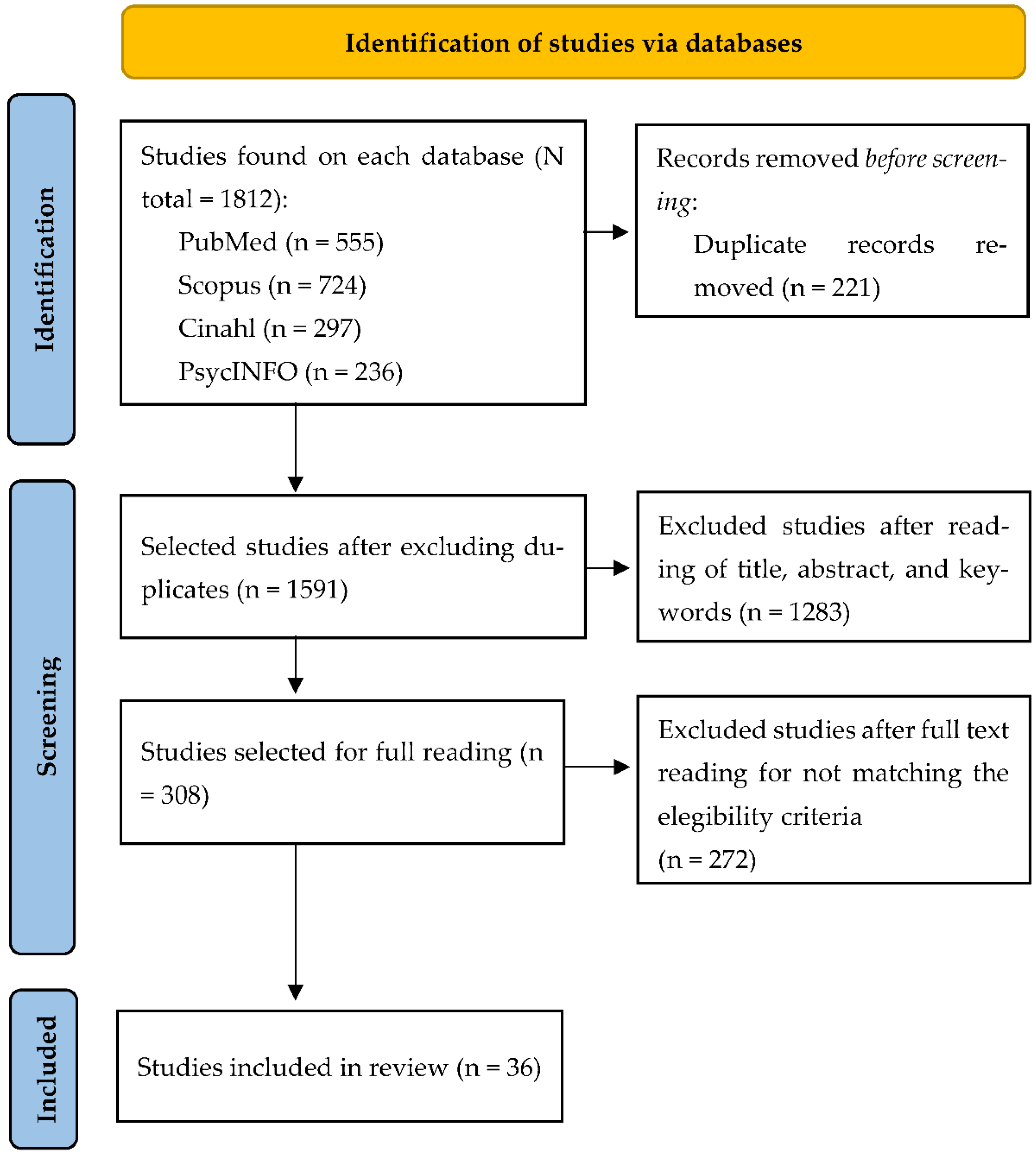

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Selection of Articles

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Description of the Studies

3.2. Study Outcome

3.2.1. Characteristics of the Sample of Caregivers of Adults with Cancer

3.2.2. Problems (Physical, Emotional, Social, and Financial) of People Who Are Caregivers of Adults with Cancer

3.2.3. Strategies to Improve the Quality of Life of Caregivers of Adults with Cancer

| Author/s and Year | Objective | Country/Period | Type of Study/Instrument/Sample | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arias-Rojas et al., 2022 [32] | To adapt and validate a LatAm-Spanish version of the QOLLTI-F scale applied to family caregivers of patients in palliative care. | Colombia/May to November 2019 | Quantitative study (descriptive) Instrument: QOLLTI-F. Sample: 208 caregivers (44 men and 164 women, average age: 49.67 years) | Deterioration of social interaction, medical care, and meaning of life. Caregivers are mostly women, daughters, or spouses/partners. They showed low quality of life, being the emotional dimension the most affected, with a significant increase in anxiety and depression levels. Strategy: Consider essential to detect exhaustion in the role of caregiver. Social support is required, besides developing strategies which allow a better management and control of the situation. This coping mechanism must be also addressed to reduce emotional impact. |

| Benites et al., 2022 [22] | Understand the spiritual and existential experiences of family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer facing end of life in Brazil. | Brazil/June 2018–March 2019 | Qualitative study through interviews Sample: 16 caregivers (3 men and 13 women, average age: non-described) | Family caregivers experienced existential and spiritual distress in the form of guilt, emotional repression, and loneliness when facing end of life. Strategy: It is required to provide training to health professional on the management of existential and spiritual distress of caregivers. |

| Sadigh et al., 2022 [56] | (1) Validate the instrument Comprehensive Score for Financial Toxicity (COST) modified in non-professional caregivers of patients with cancer, (2) Identify factors associated with financial toxicity both in patients and caregivers, and (3) Evaluate the impact of financial toxicity in specific aspects of both patients and caregivers. | USA/January–September 2019 | Quantitative study (observational cross-sectional) Instrument: questionnaire COST for non-professional caregivers, FACT-G, CarGOQoL, Brief-POMS, and MCSDS. Sample: 100 caregivers (45 men and 55 women, average age: 56.6 years) | Caregiving generates financial toxicity for caregivers due to costs growth and income loss. This financial toxicity may be even increase when care provision extends over time and the burden on the caregiver is greater. Increase of financial toxicity of caregiver correlates with higher care non-adherence in patients, increased lifestyle-altering behaviors, and low quality of life. |

| Kassir et al., 2021 [36] | Evaluate if psychosocial distress among caregivers of patients with head and neck cancer is associated with a difference in how caregivers and their patients perceive patients’ quality of life. | USA/August 2019–April 2020 | Quantitative study (cross-sectional) Instrument: UWQOL, PHQ-8, and GAD-7 Sample: 47 caregivers (14 men and 33 women, average age: 62.6 years) | Caregivers were predominantly women and spouses or partners of the patient, with a dedication to care exceeding nine hours/week. Most caregivers had spent more than one year providing care. Caregivers perceived their quality of life in a more negative way than patients with cancer, showing considerably greater levels of distress. Strategy: Facilitate meetings between patients and caregivers which allowed them to express their thoughts and feelings about the disease process and thus share how their own well-being was affected. |

| Lim et al., 2021 [40] | Examine the lifestyle of caregivers of family members with cancer, particularly the meaning of leisure and focusing on their difficulties and the role of leisure. | South Korea/Period: Non-described | Qualitative study through interviews. Sample: −10 caregivers (1 man and 9 women, average age: 44.7 years) | Caregivers showed high levels of stress and both psychological and physical conflicts, resulting in poor quality of life. Caregivers described that leisure was necessary and could improve their quality of life; however, indicated feeling of guilt when engaging in personal activities. |

| Nayak and George, 2021 [53] | Determine the effectiveness of multicomponent intervention on quality of life of family caregivers of cancer patients. | India/November 2016–February 2019 | Quantitative study (case and control) Instrument: QOLLTI-F. Sample: 200 family caregivers (78 men and 122 women, average age: 41 years) | Non-professional caregivers had to face financial problems due to the disease condition of their loved one. Lack of financial support received from other family members influenced their low quality of life. Likewise, caregivers faced difficulties in their work life and family relations. Strategy: Yoga breathing exercises, counselling and training conducted by yoga therapists. The program resulted effective in improving the quality of life of caregivers. |

| Abbasi et al., 2020 [57] | Determine the relation between care burden and quality of life of caregivers of patients with cancer in a referral hospital in Iran. | Iran/2018 | Quantitative study (cross-sectional) Instrument: SF-36, Caregiver Burden Inventory. Sample: 154 family caregivers (46 men and 108 women, average age: 41.30 years) | Increase of care burden resulted in a significant decrease of quality of life of caregivers. Besides, it was found that married caregivers had better quality of life than single ones, and caregivers with mid-high incomes reported a higher quality of life in comparison with those having a lower income. Strategy: It is recommended to reinforce and expand the support networks for caregivers of patients with cancer. Facilitate access to self-help associations. |

| El-Jawahri et al., 2020 [45] | Evaluate viability and preliminary efficacy of multimodal psychosocial intervention for family caregivers of patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation designed to improve quality of life, burden, mood, and self-efficacy of caregivers. | USA/December 2017–April 2019 | Randomized controlled trial Instrument: CarGOQOL, CRA, HADS, CASE-T, and MOCS. Sample: 100 caregivers (28 men and 72 women, average age: 61 years) | Caregivers of patients experience psychological problems (depression and anxiety) and has an overload of care throughout the care process. Strategy: Psychosocial multimodal conducted by a team of oncologists and psychologists. Caregivers who were randomized to the intervention group reported better quality of life, less overload, less anxiety and depression symptoms, more self-efficacy and coping skills when compared to the control group. |

| Halkett et al., 2020 [35] | Explore the lived experienced by caregivers of patients diagnosed with head and neck cancer. | Australia/November 2018–June 2019 | Qualitative study through interviews. Sample: 20 caregivers (1 man and 19 women, average age: 56 years) | Caregivers showed high levels of distress processed without the support of their partners or families, with the aim of minimizing patient’s distress. Silent suffering reveals the importance of communication and sharing to mitigate distress levels. Strategy: Offer training to caregivers on the disease management, fostering communication and support to reduce anxiety and distress levels. This would help to face changes in lifestyle resulting from their role as caregivers. |

| Pereira et al., 2020 [46] | Assess the relation between sociodemographic, clinical, and psychological variables with quality of life and the moderating role of caregivers’ age and the caregiving duration in caregivers of patients with multiple myeloma. | Portugal/Period: Non-described | Quantitative study (cross-sectional) Instrument: HADS, SSSS, CarGOQoL, CAMI, BIS, and SF-SUNS. Sample: 118 caregivers (45 men and 73 women, average age: 58.67 years) | Study shows that family caregivers are mostly women, patients’ spouses, or elder daughters. The burden in caregivers has been associated with high levels of stress and fatigue due to concern, insecurity, and social isolation. Besides, most caregivers possess no skills which guarantee their own well-being. Strategies: Develop coping strategies through psychological intervention programs. These strategies have been associated with a better attitude of the caregiver, which would help to lessen the emotional impact of caregivers and improve their quality of life. |

| Reblin et al., 2020 [41] | (1) Describe communication quality between patients with cancer and their spouse caregivers through observation methods, and (2) evaluate the association between communication patient-caregiver and psychological and physical health. | USA/Period: Non-described | Quantitative study (prospective observational) Instrument: HADS and PSS. Sample: 81 caregivers (23 men and 58 women, average age: 64.95 years) | Communication difficulties in partner carers of patients with cancer causes discomfort in the latter, as well as emotional and physical health issues in both. Strategy: provide caregivers opportunities to express their concerns and communicate their emotional needs outside their relationships, and thus improve their well-being. Facilitate the access to support groups, reducing the possible logistic barriers that may prevent caregivers to attend. |

| Titler et al., 2020 [47] | Assess participants’ acceptability of the FOCUS program, a psychoeducational intervention, delivered to multiple patient–caregiver dyads in a small-group format. | USA/Period: Non-described | Mixed study Instrument: FOCUS Satisfaction Instrument. Sample: 36 caregivers (16 men and 20 women, average age: 55.9 years) | The lack of communication between patient and caregiver generates depression, anxiety, and distress issues. Strategy: Psychoeducational conducted by nurses. Participants felt the benefits of being able to speak their mind about their concerns and listen to other people’s thoughts, as well as the openness and ease of talking to other couples in similar situations. |

| Abdullah et al., 2019 [48] | Examine quality of life in relation with health in caregivers of patients with gastrointestinal cancer in combination with sociodemographic factors and other related with caregiving. | Malaysia/September 2017–February 2018 | Quantitative study (cross-sectional) Instrument: CSI-M, MSPSS-M, and MCQOL. Sample: 323 family caregivers (103 men and 220 women, average age: 44.50 years) | Caregiver’s sex, ethnicity, and strain, as well as duration of caregiving provision were significantly associated with their quality of life. There was an inverse relationship among caregiving strain, duration of caregiving, and caregiver’s quality of life. Strategy: Health professionals must be able to identify groups at-risk, offering them the resources needed to improve their quality of life, including psychological therapy and access to support groups. |

| Baudry et al., 2019 [33] | Identify the profiles of caregivers at higher risk of having at least one moderately or highly unmet supportive care need based on socio-demographic and clinical variables highlighted in the literature. | France/18 months; year not further specified. | Quantitative study (descriptive cross-sectional) Instrument: SCNS-P&C-F, and HADS. Sample: 364 caregivers (131 men and 233 women, average age: 58.05 years) | The main problem of caregivers lies in the risk of suffering anxiety and depression depending of the type of cancer of the relative they provide care to. Likewise, caregivers show difficulty in controlling their emotional state. Strategy: Routine evaluation of anxiety and depression symptoms of caregivers to prevent risk of emotional overload. |

| De Camargos et al., 2019 [23] | Analyze and compare what oncologic patients, non-professional caregivers, and healthy population think could make them happy. | Brazil/October 2015–October 2016 | Qualitative study through interviews. Sample: 126 caregivers (28 men and 98 women, average age: non-described) | Among problems or concerns suffered by caregivers, there is risk of depression, anxiety, and distress. Strategy: Develop psychoeducational and cognitive-behavioral strategies which help to improve the caregivers’ quality of life. These strategies should be addressed to cope with emotional overload derived from caregiving, among other concerns. |

| Hsu et al., 2019 [49] | (1) Characterize non-professional caregivers of hospitalized older adults with cancer, (2) determine the caregiver’s quality of life, and (3) identify the factors associated with a worse quality of life of the caregiver. | USA/July 2013–January 2014 | Quantitative study Instrument: CQOLC, CCI, MHI-18, MOS, MOS-SSS, OARS-IADL, MOS-physical health scale, and KPS. Sample: 100 family caregivers (28 men, and 72 women, average age: 65 years) | Most caregivers qualified their own health as good vs a lower percentage which referred a worsening of their health condition due to caregiving. Caregivers performed a median of 35 h of care per week. A lower quality of life in the caregiver was associated with worse mental health, less social support, and worse score in both Karnofsky and patient scales. Strategy: Develop strategies, including training, skills, and guidance on how to provide care to patients, to improve the quality of life of the caregiver, their physical well-being and self-efficacy. |

| Kehoe et al., 2019 [42] | Evaluate the relationships between aging-related domains captured by geriatric assessment for older patients with advanced cancer and caregivers’ emotional health and quality of life. | USA/October 2014–April 2017 | Quantitative study (cross-sectional) Instrument: Geriatric Scale, PHQ-2, GAD-7, and SF-12 Sample: 411 family caregivers (101 men and 310 women, average age: 66.5 years) | Almost half of the caregivers described feelings of distress, anxiety, and depression. A greater decline in the patients’ geriatric scale was associated with higher levels of depression and worsening of physical health and quality of life of caregivers. Besides, when the caregiver was younger and had greater number of comorbidities, their quality of life were worse. |

| Kilic y Oz, 2019 [24] | Assess quality of life of family caregivers of patients with cancer in Türkiye. | Türkiye/Period: Non-described | Quantitative study (descriptive) Instrument: QoL-FV. Sample: 378 family caregivers (135 men and 243 women, average age: non-described) | 81% of the sample reported that the disease process affected their lives negatively, particularly the social and work spheres. There were significant differences between the quality of life of caregivers and their sex, education level, work situation, income level, relation with patients, and if they lived with their patients or not. Strategy: Develop strategies addressed to coping, knowledge and communication, physical activities, and search of support networks. Health professionals should conduct their strategies with an approach focused on the whole family. |

| Kristanti et al., 2019 [25] | Explore the experiences of family caregivers of patients with cancer in the performance of their care provision in Indonesia. | Indonesia/July 2015–March 2016 | Qualitative study through interviews. Sample: 24 caregivers (8 men and 16 women, average age: non-described) | Most caregivers reported a physical impact resulting from their role of caregiver, with feelings of fatigue or a tendency to ignore their condition. Due to constant concern, fear, and permanent state of alert, there was a significant impact at an emotional level. Regarding their economic status, both families with low incomes and those of higher income suffered the consequences of the need of providing the best care. At a social level, some positive changes were reported, such as the acquisition of new values and greater family cohesion. |

| Shin et al., 2019 [43] | Explore the association between the needs of health care and quality of life of family caregivers of people with cancer in Korea, according to time lapse after cancer diagnosis. | South Korea/June 2014–April 2017 | Quantitative study (cross-sectional) Instrument: CNAT-C and EQ-5D-3L. Sample: 686 caregivers (239 men and 447 women, average age: 49 years) | Female caregivers or older caregivers had a lower quality of life and greater unmet needs (at the health/psychological problems and religious/spiritual support dimensions) in questionnaires when compared to results of male or younger caregivers. |

| Steel et al., 2019 [37] | Examine psychosocial and behavioral predictors of metabolic syndrome in caregivers of patients with cancer. | USA/November 2016–August 2018 | Quantitative study (prospective) Instrument: CES-D, PSS, CQOLC, Cook-Medley Hostility Scale, PSQI, IPAQ, Substance use questionnaire, The Revised UCLA Loneliness scale, ISEL, DAS-7. Sample: 104 caregivers (24 men and 80 women, average age: 59.5 years) | Almost half of caregivers included in the study met the criteria for metabolic syndrome, showing with above average figures than that of the general population. The study did not associate depressive syndrome and metabolic syndrome. Strategy: Design and test adapted strategies addressed to specific health behaviors, as well as psychological factors (caregiver’s quality of life) to reduce metabolic anomalies in caregivers of patients with cancer. |

| Van Roij et al., 2019 [54] | Explore the social consequences of advanced cancer in patients and non-professional caregivers. | Netherlands/January–June 2017 | Qualitative study through focal groups. Sample: 15 caregivers (6 men and 9 women, average age: 58 years) | Caregivers described difficulties in reconciling their role as caregiver with the rest of daily life activities. Besides, they described abandonment of social spheres due to lack of time/energy, or feelings of shame/guilt for letting patients in other people’s care. Caregivers described feeling uneasy at social events, as most interactions were focused on cancer. Strategy: Help caregivers to express their feelings with respect to social situations through both psychological support and social awareness. Additionally, raise awareness among health professionals with respect to cancer social impact dimension. |

| Wittenberg et al., 2019 [26] | Explore the differences in the domains of health literacy among family caregiver communication types. | USA/March 2018–June 2018 | Quantitative study (descriptive) Instrument: FCCT, HLCS-C Sample: 115 caregivers (38 men and 77 women, average age: non-described) | There were significant differences in the domains of health literacy among family caregiver communication types regarding cancer discussion with the patient and general understanding of health system. A lack of communication regarding the disease on the part of the caregiver has been positively associated with depression in the caregiver. Strategy: Develop communication and cultural awareness skills in the care provider to ensure a quality communication. |

| Wood et al., 2019 [55] | Quantify the humanistic burden associated with caring for patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer from the caregiver’s perspective, including quality of life, in three different European countries. | France, Germany, and Italy/May 2015–June 2016 | Quantitative study (multicenter, cross-sectional) Instruments: EQ-5D-3L, Zarit Burden Interview y WPAI:GH Sample: 427 caregivers (120 men and 307 women, average age: 53.5 years) | There were significant differences in the results of EQ-5D-3L questionnaire among caregivers receiving first-line therapy and later lines of therapy. Caregivers receiving the later lines rated their own health status significantly worse than caregivers receiving first-line therapy. General work impairment was considerable among employed caregivers. |

| Bilgin y Gozum, 2018 [27] | Identify the needs of nursing care given at home of both patients with stomach cancer and their caregivers, as well as the effect of family nursing care in the quality of life of both patients and their families. | Türkiye/Period: Non-described | Experimental controlled trial. Instrument: QLQ-C30, CQOLC Sample: 72 caregivers (27 men and 45 women, average age: non-described) | The assessment of the quality of life showed that caregivers presented significant changes in the dimensions of psychological strain, disruption in daily life, and care responsibility. There were no significant changes in the subscale of financial concerns. Strategy: Home care performed by nurses and focused on lack of knowledge, diagnosis of despair, anxiety, isolation/social decline. Care provided improved the scores of caregivers’ quality of life when compared to baseline situation. |

| Cho et al., 2018 [28] | Compare depression prevalence in relatives of patients with cancer and general population. | South Korea/2007–2014 | Quantitative study Instruments: Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Sample: 1590 caregivers (811 men and 779 women, average age: non-described) | The odds of having medically diagnosed depression in caregivers of patients with cancer were significantly higher than those of the general population. Strategy: Invest more effort in the diagnosis and management of depression in families of patients with cancer in order to improve their quality of life and the patient’s well-being. |

| Cubukcu, 2018 [44] | Assess quality of life and factors affecting caregivers of patients with cancer who receive care at home. | Türkiye/February de 2014 | Quantitative study (cross-sectional descriptive) Instrument: CQOLC, Katz index, and Lawton index. Sample: 48 caregivers (8 men and 40 women, average age: 50.75 years) | Caregivers describe a worsening of their health. More than 90% of caregivers declare having psychological issues, and 9% confirm suffering physical decline. More than half revealed not having time to fulfill their responsibilities due to caregiving process. Quality of life is lower when caregivers are family, there is a lack of social insurance, care provision exceeds the year of duration, and income is low. Strategy: Personal situations of caregivers must be considered, analyzing their needs, and offering them both material and spiritual support. |

| Cuthbert et al., 2018 [34] | Examine the effects of a 12-week exercise program on the quality of life, psychological outcomes, physical activity levels, and physical fitness in caregivers of patients with cancer. | Canada/May 2015–February 2016 | Randomized controlled trial (case and control) Sample: 100 caregivers (39 men and 61 women, average age: 53.25 years) | Family caregivers of patients with cancer are at risk of suffering greater physical and psychological morbidity as a result of their role as caregivers. Strategy: Exercise program conducted by a certified personal trainer and a kinesiology student volunteer. The strategy was effective in improving the physical condition of caregivers. |

| Hyde et al., 2018 [50] | Examine psychological distress specific in the partner of the patient with prostate cancer over two years, as well predictors of change. | Australia/January 2009–November 2010 | Quantitative study Instrument: HADS, IES-R, Caregiver Burden scale, partner version of the Self-Efficacy for Symptom Control Inventory, two subscales to evaluate stress, 7-item Dyadic Adjustment Scale. Sample: 427 caregivers (0 men and 427 women, average age: 62.8 years) | Female caregivers of patients with prostate cancer referred significant psychological distress with high levels of anxiety and depression. Partners with greater burden in their role as caregiver showed greater psychological tension in comparison with those having less. More self-efficacy on the part patient was associated to less psychological discomfort in the caregiver. Strategy: Increase information on the disease process and care at home, provide practical and emotional support to caregivers, offering them different resources such as social network support, and strengthen their psychological resilience. |

| McDonald et al., 2018 [29] | Conceptualize quality of life of caregivers from their own perspective and explore the differences in themes between those who did or did not receive an early palliative care intervention. | Canada/December 2006–February 2011 | Qualitative study through semi-structured interviews Sample: 23 caregivers (7 men and 16 women, average age: non-described) | Caregivers felt insecure about how to face the end of life of relatives they provided care to, as they felt they lacked knowledge. Strategy: Support on palliative care conducted by specialized doctors and nurses. They shared an open discussion on end of life, trying to balance hope and reality, and increased confidence from a range of professional supports. |

| Tan et al., 2018 [51] | Explore the interrelations between care burden, emotional state, and quality of life of caregivers of patients with lung cancer and research the association between health results of both caregiver and patient. | England/Period: Non-described | Quantitative study (exploratory cross-sectional) Instrument: CBS, CQOLC, HADS and LCSS. Sample: 43 caregivers (15 men and 28 women, average age: 61.7 years) | 46.5% caregivers were identified as anxious and 27.9% as depressed. Those caregivers experiencing anxiety and depression scored worse quality of life and higher burden when compared with those non-anxious and non-depressed caregivers. Depressive emotional state in patients seemed to be associated with higher emotional distress in caregivers. |

| Washington et al., 2018 [38] | Examine both viability and impact of problem-solving therapy for caregivers of patients with cancer receiving outpatient palliative care. | USA/October 2015–February 2017 | Randomized controlled trial Instrument: PST, GAD-7, PHQ-9, CQLI-R Sample: 83 caregivers (26 men and 57 women, average age: 51.5 years) | Caregivers described high psychological strain tension and high levels of anxiety and depression which directly affected their quality of life. Strategy: Problem-solving therapy conducted by nurses. Participants informed of lower anxiety levels. However, no significant differences were observed regarding caregivers’ depression or quality of life. |

| Yu et al., 2018 [39] | Evaluate quality of life related to the health of family caregivers of patients with leukemia using the health-related utility scores derived from questionnaire EQ-5D. | China/July 2015–February 2016 | Quantitative study (cross-sectional) Instrument: EQ-5D-3L, HADS, SSRS, family APGAR Sample: 306 caregivers (139 men and 167 women, average age: 41.20 years) | Caregivers showed lower scores in EQ-5D-3L questionnaire than general population. Participants of a lower socioeconomic status had lower scores and reported more problems that those with a higher socioeconomic status. Strategy: Offering and promoting both financial and social support may be key to improve the quality of life of family caregivers. |

| Lee et al., 2017 [52] | Explore the mood changes and quality of life in caregivers of patients with head and neck cancer and examine the prevalence and risk factors of depressive disorders among caregivers of patients suffering this type of cancer. | Taiwan/February 2012–January 2013 | Quantitative study (prospective) Instrument: SCID-CV, HADS, SF-36, and Family APGAR Index. Sample: 132 caregivers (30 men and 102 women, average age: 47.2 years) | During the 6-month follow-up, depression and anxiety severity in caregivers decreased, which significantly improved their quality of life. After six months, most prevalent psychiatric disorders were depression-related, followed by alcohol abuse and primary insomnia. Study revealed that older ages, the use of hypnotic drugs, pre-existing depression, and lower mental component of SF-36 score at baseline were found to significantly predict depressive disorders in caregivers of patients with these types of cancer. |

| Mollica et al., 2017 [30] | Examine association between the receipt of medical/nursing skills training and the caregiver burden as well as the mediation of caregiving confidence on this relationship. | USA/Period: non-described | Quantitative study (cross-sectional) Instrument: ZBI (short version), 2 questions to measure receipt of medical/nursing skills and 1 question to measure the caregiver’s training. Sample: 641 caregivers (125 men and 516 women, average age: non-described) | Caregivers reported moderate levels of burden. Lack of receipt of training was associated with greater levels of burden in their role as caregivers. Confidence partially mediated the relation between training and burden. Strategy: Authors highlighted the need of empirical studies which evaluate if training in medical/nursing skills for caregivers of patients with cancer may have an impact in the outcomes of caregivers over time. |

| Senneseth et al., 2017 [31] | (1) Measure the short-term effects of the Cancer-PEPSONE received social support, psychological distress, and quality of life of partners, and (2) explore social support received as a mediator of the intervention effects. | Norway/ December 2013–June 2015 | Open single-center randomized controlled trial. Instrument: CSS, MSPSS, GHQ-12, QOLS-N Sample: 35 caregivers (21 men and 14 women, average age: non-described) | The control group referred a significant decrease in perceived social support. According to this study analysis, CPP may have indirect effects in the short term on the caregivers’ quality of life through social support received. Strategy: The intervention group received a 3-h session. Evaluation: Firstly, psychoeducative aspects analyzing challenges associated to the disease and social support. Then, individual needs of each family were analyzed, exploring the resources required for each case. |

4. Discussion

4.1. Characteristics of the Sample of Caregivers of Adults with Cancer

4.2. Physical, Emotional, Social, and Financial Strain Suffered by Caregivers of Adults with Cancer

4.3. Strategies to Improve the Quality of Life of Caregivers of Adults with Cancer

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Cancer Institute. What Is Cancer? Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/understanding/what-is-cancer (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- World Health Organization. Cancer. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- Sociedad Espyearla de Oncología Médica. Las Cifras del Cáncer en Espala. Available online: https://seom.org/images/LAS_CIFRAS_DEL_CANCER_EN_ESPANA_2022.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2022).

- González, A.; Fonseca, M.; Valladares, A.M.; López, L.M. Factores moduladores de resiliencia y sobrecarga en cuidadores principales de pacientes oncológicos avanzados. Rev. Finlay 2017, 7, 26–32. [Google Scholar]

- Zambrano-Domínguez, E.M.; Guerra-Martín, M.D. Formación del cuidador informal: Relación con el tiempo de cuidado a personas dependientes mayores de 65 years. Aquichan 2012, 12, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-Rojas, M.; Carreño, S.; Sepúlveda, A.; Romero, I. Sobrecarga y calidad de vida de cuidadores de personas con cáncer en cuidados paliativos. Rev. Cuid. 2021, 12, e1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, J.A. Ansiedad y depresión en cuidadores de pacientes dependientes. Med. Fam.-SEMERGEN 2012, 38, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto de Mayores y Servicios Sociales. Cuidados a las Personas Mayores en los Hogares Espyearles: El Entorno Familiar. Available online: http://envejecimiento.csic.es/documentos/documentos/imserso-cuidados-01.pdf (accessed on 27 February 2022).

- Navarro, V. Perfil de los cuidadores informales y ámbito de actuación del trabajo social. Trab. Soc. Hoy 2016, 77, 63–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, Y.; López, E.J.; López, E.; Arredondo, B. La psicología y la oncología: En una unidad imprescindible. Rev. Finlay 2017, 7, 115–127. [Google Scholar]

- Amador-Marín, B.; Guerra-Martín, M.D. Eficacia de las intervenciones no farmacológicas en la calidad de vida de las personas cuidadoras de pacientes con enfermedad de Alzheimer. Gac. Sanit. 2017, 31, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesa, P.; Ramos, M.; Redolat, R. Cuidado de pacientes oncológicos: Una revisión sobre el impacto de la situación de estrés crónico y su relación con la personalidad del cuidador y otras variables moduladoras. Psicooncología 2017, 14, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guijarro-Requena, M.D.; Marín-Campaña, M.N.; Pulido-Lozano, M.I.; Romero-Carmona, R.M.; Luque-Romero, L.G. Mejora de la calidad de vida en cuidadores informales de personas dependientes mediante talleres educacionales. Enferm. Glob. 2022, 21, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinaccia, S.; Quiceno, J.M.; Fernández, H.; Contreras, F.; Bedoya, M.; Tobón, S.; Zapata, M. Calidad de vida, personalidad resistente y apoyo social percibido en pacientes con diagnóstico de cáncer pulmonar. Psicol. Salud 2005, 15, 207–221. [Google Scholar]

- The WHOQOL Group. The World Health Organization Quality of Life assessment (WHOQOL): Position paper from the World Health Organization. Soc. Sci. Med. 1995, 41, 1403–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schalock, R.L.; Verdugo, M.A. Calidad de vida. In Discapacidad e Inclusión, 1st ed.; Alianza Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rogero-García, J. Distribución en España del cuidado formal e informal a las personas mayores de 65 y más years en situación de dependencia. Rev. Espyearla Salud Pública 2009, 83, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, E. La Calidad de vida de las Cuidadoras Informales: Bases para un Sistema de Valoración. Available online: https://www.seg-social.es/wps/wcm/connect/wss/c3f111db-d9a6-4ee8-adfd-cbd7f9a8e99c/F74_07.pdf?MOD=AJPERES (accessed on 8 March 2022).

- Villatoro, K.; Sánchez, V. Calidad de vida y calidad de vida relacionada con la salud. In Atención al Tratamiento de las Enfermedades Crónicas Desde el Centro de Salud; Villatoro, K., Sánchez, V., Eds.; Universidad de Valencia: Valencia, Spain, 2012; pp. 29–46. [Google Scholar]

- Del Pino, R.; Frías, A.; Palomino, P.A. La revisión sistemática cuantitativa en enfermería. Rev. Iberoam. Enferm. Comunitaria 2014, 7, 24–39. [Google Scholar]

- Perestelo-Pérez, L. Standars on how to develop and report systematics reviews in Psychology and Health. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2013, 13, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benites, A.C.; Rodin, G.; De Oliveira-Cardoso, E.A.; Dos Santos, M.A. “You begin to give more value in life, in minutes, in seconds”: Spiritual and existential experiences of family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer receiving end-of-life care in Brazil. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 2631–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Camargos, M.G.; Paiva, B.; De Almeida, C.; Paiva, C.E. What Is Missing for You to Be Happy? Comparison of the Pursuit of Happiness among Cancer Patients, Informal Caregivers, and Healthy Individuals. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2019, 58, 417–426.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilic, S.T.; Oz, F. Family Caregivers’ Involvement in Caring with Cancer and their Quality of Life. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2019, 20, 1735–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristanti, M.S.; Effendy, C.; Utarini, A.; Vernooij-Dassen, M.; Engels, Y. The experience of family caregivers of patients with cancer in an Asian country: A grounded theory approach. Palliat. Med. 2019, 33, 676–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittenberg, E.; Goldsmith, J.V.; Kerr, A.M. Variation in health literacy among family caregiver communication types. Psychooncology 2019, 28, 2181–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilgin, S.; Gozum, S. Effect of nursing care given at home on the quality of life of patients with stomach cancer and their family caregivers’ nursing care. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2018, 27, e12567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, Y.; Jeon, Y.; Jang, S.I.; Park, E.C. Family Members of Cancer Patients in Korea Are at an Increased Risk of Medically Diagnosed Depression. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 2018, 51, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, J.; Swami, N.; Pope, A.; Hales, S.; Nissim, R.; Rodin, G.; Hannon, B.; Zimmermann, C. Caregiver quality of life in advanced cancer: Qualitative results from a trial of early palliative care. Palliat. Med. 2018, 32, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mollica, M.A.; Litzelman, K.; Rowland, J.H.; Kent, E.E. The role of medical/nursing skills training in caregiver confidence and burden: A CanCORS study. Cancer 2017, 123, 4481–4487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senneseth, M.; Dyregrov, A.; Laberg, J.; Matthiesen, S.B.; Pereira, M.; Hauken, M.A. Facing spousal cancer during child-rearing years: The short-term effects of the Cancer-PEPSONE programme-a single-center randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology 2017, 26, 1541–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-Rojas, M.; Arredondo, E.; Carreño, S.; Posada, C.; Tellez, B. Validation of the Latin American-Spanish version of the scale ‘Quality of Life in Life-Threatening Illness-Family Caregiver Version’ (QOLLTI-F). Health Soc. Care Community 2022, 30, e832–e841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudry, A.S.; Vanlemmens, L.; Anota, A.; Cortot, A.; Piessen, G.; Christophe, V. Profiles of caregivers most at risk of having unmet supportive care needs: Recommendations for healthcare professionals in oncology. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. Off. J. Eur. Oncol. Nurs. Soc. 2019, 43, 101669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuthbert, C.A.; King-Shier, K.M.; Ruether, J.D.; Tapp, D.M.; Wytsma-Fisher, K.; Fung, T.S.; Culos-Reed, S.N. The Effects of Exercise on Physical and Psychological Outcomes in Cancer Caregivers: Results from the RECHARGE Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann. Behav. Med. 2018, 52, 645–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halkett, G.K.; Golding, R.M.; Langbecker, D.; White, R.; Jackson, M.; Kernutt, E.; O’Connor, M. From the carer’s mouth: A phenomenological exploration of carer experiences with head and neck cancer patients. Psychooncology 2020, 29, 1695–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassir, Z.M.; Li, J.; Harrison, C.; Johnson, J.T.; Nilsen, M.L. Disparity of perception of quality of life between head and neck cancer patients and caregivers. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, J.L.; Cheng, H.; Pathak, R.; Wang, Y.; Miceli, J.; Hecht, C.L.; Haggerty, D.; Peddada, S.; Geller, D.A.; Marsh, W.; et al. Psychosocial and behavioral pathways of metabolic syndrome in cancer caregivers. Psychooncology 2019, 28, 1735–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Washington, K.T.; Demiris, G.; Parker, D.; Albright, D.L.; Craig, K.W.; Tatum, P. Delivering problem-solving therapy to family caregivers of people with cancer: A feasibility study in outpatient palliative care. Psychooncology 2018, 27, 2494–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Zhang, H.; Yang, J.; Liu, C.; Lu, C.; Yang, H.; Huang, W.; Zhou, J.; Fu, W.; Shi, L.; et al. Health utility scores of family caregivers for leukemia patients measured by EQ-5D-3L: A cross-sectional survey in China. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Cho, H.; Bunds, K.S.; Lee, C.W. Cancer family caregivers’ quality of life and the meaning of leisure. Health Care Women Int. 2021, 42, 1144–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reblin, M.; Otto, A.K.; Ketcher, D.; Vadaparampil, S.T.; Ellington, L.; Heyman, R.E. In-home conversations of couples with advanced cancer: Support has its costs. Psychooncology 2020, 29, 1280–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehoe, L.A.; Xu, H.; Duberstein, P.; Loh, K.P.; Culakova, E.; Canin, B.; Hurria, A.; Dale, W.; Wells, M.; Gilmore, N.; et al. Quality of Life of Caregivers of Older Patients with Advanced Cancer. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 969–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, J.; Ko, H.; Lee, J.W.; Kim, K.; Song, Y.M. Influence of time lapse after cancer diagnosis on the association between unmet needs and quality of life in family caregivers of Korean cancer patients. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2019, 28, e13089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cubukcu, M. Evaluation of quality of life in caregivers who are providing home care to cancer patients. Support. Care Cancer 2018, 26, 1457–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Jawahri, A.; Jacobs, J.M.; Nelson, A.M.; Traeger, L.; Greer, J.A.; Nicholson, S.; Waldman, L.P.; Fenech, A.L.; Jagielo, A.D.; D’Alotto, J.; et al. Multimodal psychosocial intervention for family caregivers of patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: A randomized clinical trial. Cancer 2020, 126, 1758–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, M.G.; Vilaça, M.; Pinheiro, M.; Ferreira, G.; Pereira, M.; Faria, S.; Monteiro, S.; Bacalhau, R. Quality of life in caregivers of patients with multiple myeloma. Aging Ment. Health 2020, 24, 1402–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titler, M.G.; Shuman, C.; Dockham, B.; Harris, M.; Northouse, L. Acceptability of a Dyadic Psychoeducational Intervention for Patients and Caregivers. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2020, 47, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdullah, N.N.; Idris, I.B.; Shamsuddin, K.; Abdullah, N. Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQOL) of Gastrointestinal Cancer Caregivers: The Impact of Caregiving. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2019, 20, 1191–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, T.; Nathwani, N.; Loscalzo, M.; Chung, V.; Chao, J.; Karanes, C.; Koczywas, M.; Forman, S.; Lim, D.; Siddiqi, T. Understanding Caregiver Quality of Life in Caregivers of Hospitalized Older Adults with Cancer. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 978–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, M.K.; Legg, M.; Occhipinti, S.; Lepore, S.J.; Ugalde, A.; Zajdlewicz, L.; Laurie, K.; Dunn, J.; Chambers, S.K. Predictors of long-term distress in female partners of men diagnosed with prostate cancer. Psychooncology 2018, 27, 946–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, J.Y.; Molassiotis, A.; Lloyd-Williams, M.; Yorke, J. Burden, emotional distress and quality of life among informal caregivers of lung cancer patients: An exploratory study. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2018, 27, e12691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.Y.; Lee, Y.; Wang, L.J.; Chien, C.Y.; Fang, F.M.; Lin, P.Y. Depression, anxiety, quality of life, and predictors of depressive disorders in caregivers of patients with head and neck cancer: A six-month follow-up study. J. Psychosom. Res. 2017, 100, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, M.G.; George, A. Effectiveness of Multicomponent Intervention on Quality of Life of Family Caregivers of Cancer Patients. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2021, 22, 2789–2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Roij, J.; Brom, L.; Youssef-El Soud, M.; Van de Poll-Franse, L.; Raijmakers, N. Social consequences of advanced cancer in patients and their informal caregivers: A qualitative study. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 1187–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, R.; Taylor-Stokes, G.; Lees, M. The humanistic burden associated with caring for patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in three European countries-a real-world survey of caregivers. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 1709–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadigh, G.; Switchenko, J.; Weaver, K.E.; Elchoufi, D.; Meisel, J.; Bilen, M.A.; Lawson, D.; Cella, D.; El-Rayes, B.; Carlos, R. Correlates of financial toxicity in adult cancer patients and their informal caregivers. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, A.; Mirhosseini, S.; Basirinezhad, M.H.; Ebrahimi, H. Relationship between caring burden and quality of life in caregivers of cancer patients in Iran. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 4123–4129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez, L.; Lorenzo, A.; Llantá, M.C. Carga del cuidador en cuidadores informales primarios de pacientes con cáncer de cabeza y cuello. Rev. Habanera Cienc. Méd. 2019, 18, 126–137. [Google Scholar]

- Sotés, J.R.; Artime, M.; Pérez, A.; Olivera, B.; Martínez, L. Enfrentamiento a la muerte por cuidadores informales de pacientes con cáncer en estado terminal. Acta Méd. Cent. 2021, 15, 591–604. [Google Scholar]

- Vélez, J.A.; Mora, M.L.; Piedra, M.J. Bienestar y apoyo social en cuidadores informales de pacientes oncológicos. Eureka 2022, 19, 54–72. [Google Scholar]

- Peredo, E.; Gutiérrez, A.G.; Ortega, M.E.; Gutiérrez, C.; Contreras, C.M. Síndrome de burnout, ansiedad, depresión y ciclo reproductivo en cuidadoras informales de pacientes con cáncer. Psicol. Salud 2022, 32, 325–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amador, C.; Puello, E.C.; Valencia, N.N. Características psicoafectivas y sobrecarga de los cuidadores informales de pacientes oncológicos terminales en Montería, Colombia. Rev. Cuba. Salud Pública 2020, 46, e1463. [Google Scholar]

- Rizo, A.C.; Molina, M.; Milián, N.C.; Pagán, P.E.; Machado, J. Caracterización del cuidador primario de enfermero oncológico en estado avanzado. Rev. Cuba. Med. Gen. Integral 2016, 32, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart, M.; Sorensen, S. Correlates of Physical Health of Informal Caregivers: A Meta-Analysis. J. Gerontol. 2007, 62, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrón, B.S.; Alvarado, S. Desgaste físico y Emocional del Cuidador Primario en Cáncer. Cancerología 2009, 4, 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- García, M.M.; Del Río, M. El papel del cuidado informal en la atención a la dependencia: ¿cuidamos a quiénes cuidan? Actas Depend. 2012, 6, 99–117. [Google Scholar]

- Rosado, E.A.; Arroyo, C.; Sahagún, A.; Lara, A.; Campos, S.; Ochoa, R.; Sánchez, J.J. Necesidad de apoyo psicológico y calidad de vida en el cuidador primario de pacientes pediátricos con cáncer. Psicooncologia 2021, 18, 137–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shultz, R. Sherwood PR. Physical and Mental Health Effects of Family Caregiving. Am. J. Nurs. 2008, 108, 23–27. [Google Scholar]

- Cortijo-Palacios, X.; Bernal-Morales, B.; Gutiérrez-García, A.G.; Díaz-Domínguez, E.; Hernández-Baltazar, D.; Cibrián-Llanderal, T. Evaluación psicoafectiva en pacientes con cáncer avanzado y cuidadores principales. Gac. Mex. Oncol. 2018, 17, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino, K.; Murillo, M.; Suárez, L.F. Acompañamiento al enfermero crónico o terminal y calidad de vida en familia. Poiésis 2019, 36, 126–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-ordoñez, F.; Frías-Osuna, A.; Romero-Rodríguez, Y.; Del-Pino-Casado, R. Coping strategies and anxiety in caregivers of palliative cancer patients. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2016, 25, 600–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carreño, S.P.; Sánchez, B.; Carrillo, G.M.; Chaparro-Díaz, L.; Gómez, O.J. Carga de la enfermedad crónica para los sujetos implicados en el cuidado. Rev. Fac. Nac. Salud Pública 2016, 34, 342–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivar, C.G.; Orecilla-Velilla, E.; Gómara-Arraiza, L. “Es más difícil”: Experiencias de las enfermeras sobre el cuidado del paciente con recidiva de cáncer. Enferm. Clín. 2009, 19, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guerra-Martín, M.D.; Casado-Espinosa, M.D.R.; Gavira-López, Y.; Holgado-Castro, C.; López-Latorre, I.; Borrallo-Riego, Á. Quality of Life in Caregivers of Cancer Patients: A Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1570. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021570

Guerra-Martín MD, Casado-Espinosa MDR, Gavira-López Y, Holgado-Castro C, López-Latorre I, Borrallo-Riego Á. Quality of Life in Caregivers of Cancer Patients: A Literature Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(2):1570. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021570

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuerra-Martín, María Dolores, María Del Rocío Casado-Espinosa, Yelena Gavira-López, Cristina Holgado-Castro, Inmaculada López-Latorre, and Álvaro Borrallo-Riego. 2023. "Quality of Life in Caregivers of Cancer Patients: A Literature Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 2: 1570. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021570

APA StyleGuerra-Martín, M. D., Casado-Espinosa, M. D. R., Gavira-López, Y., Holgado-Castro, C., López-Latorre, I., & Borrallo-Riego, Á. (2023). Quality of Life in Caregivers of Cancer Patients: A Literature Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 1570. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021570