Suicide Prevention for International Students: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

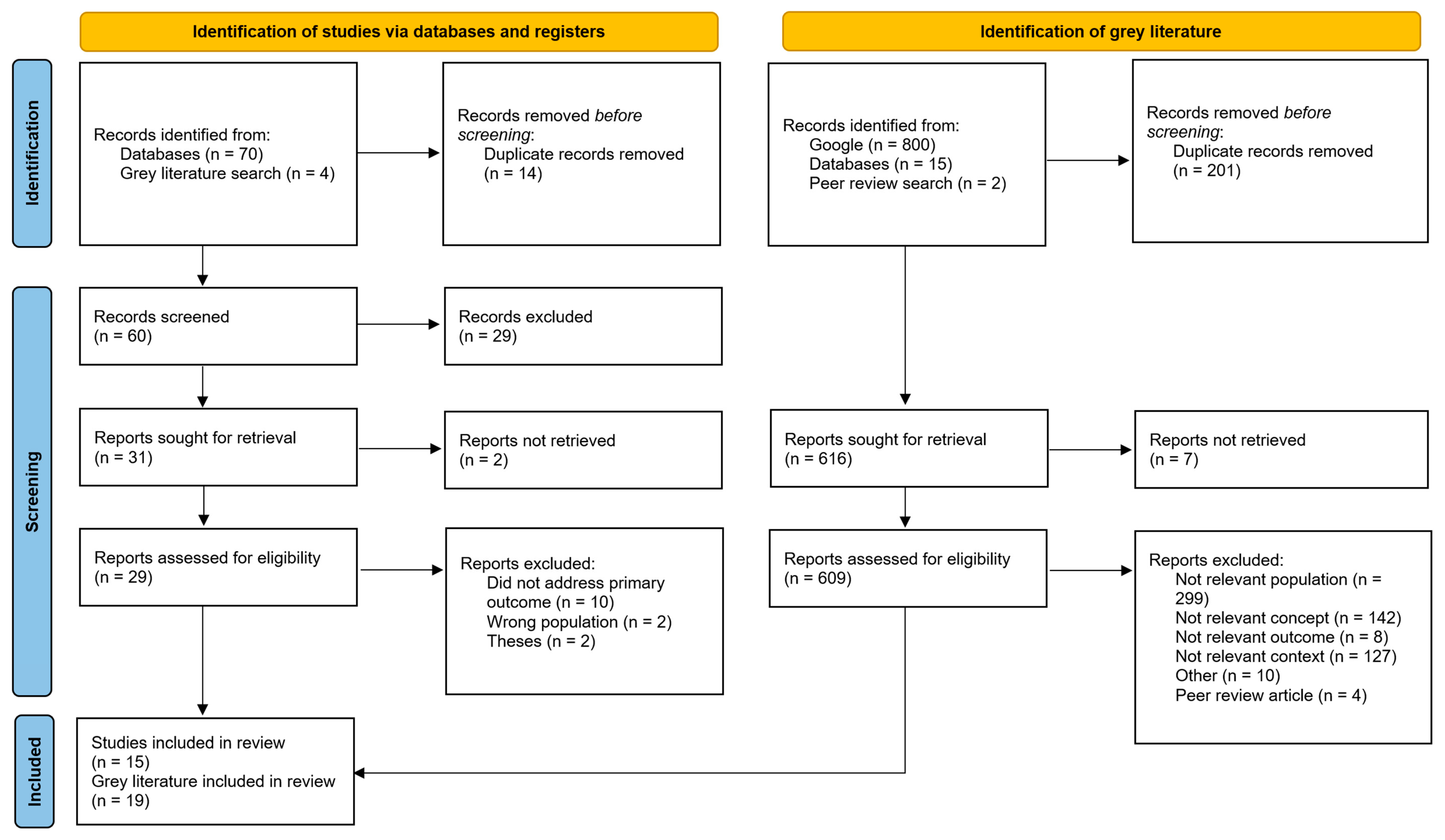

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview

2.2. Step 1: Identifying the Research Question

- What is the extent, range, and nature of the evidence regarding suicide prevention for international students?

- What suicide prevention strategies are promising for preventing suicide in international students?

2.3. Step 2: Identifying Relevant Studies

2.4. Step 3: Study Selection

2.5. Step 4: Charting the Data

2.6. Step 5: Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting the Results

2.7. Step 6: Consultation

3. Results

3.1. Peer-Reviewed Study Characteristics

3.2. Gray Literature Characteristics

3.3. Intervention Studies

3.4. International Student Suicide Prevention Recommendations

3.5. Future Research Recommendations

4. Discussion

4.1. The State of the Literature

4.1.1. Characteristics of Existing Evidence

4.1.2. Suicide Risk and Protective Factors

4.1.3. Intervention Studies

4.2. Research and Policy Directions

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Deviations from the Published Protocol

Appendix A.2. Questions and Associated Decisions during Screening Process

Appendix A.2.1. Question 1

Appendix A.2.2. Question 2

Appendix A.2.3. Question 3

Appendix A.2.4. Question 4

Appendix A.2.5. Question 5

Appendix A.2.6. Question 6

References

- Hong, V.; Busby, D.R.; O’Chel, S.; King, C.A. University Students Presenting for Psychiatric Emergency Services: Socio-Demographic and Clinical Factors Related to Service Utilization and Suicide Risk. J. Am. Coll. Health 2022, 70, 773–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolitzky-taylor, K.; Lebeau, R.T.; Perez, M.; Gong, E.; Fong, T.; Lebeau, R.T.; Perez, M.; Gong, E. Suicide Prevention on College Campuses: What Works and What Are the Existing Gaps ? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Coll. Health 2020, 68, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, M.H.; Scott, M.; Baker-Young, E.; Thompson, C.; McGarry, S.; Hayden-Evans, M.; Snyman, Z.; Zimmermann, F.; Kacic, V.; Falkmer, T.; et al. Preventing Suicide in Post-Secondary Students: A Scoping Review of Suicide Prevention Programs; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; ISBN 0123456789. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, J.; Calear, A.L. Suicide Prevention in Educational Settings: A Review. Australas. Psychiatry 2018, 26, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, J.C.; Ribeiro, J.D.; Fox, K.R.; Bentley, K.H.; Kleiman, E.M.; Huang, X.; Musacchio, K.M.; Jaroszewski, A.C.; Chang, B.P.; Nock, M.K. Risk Factors for Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors: A Meta-Analysis of 50 Years of Research. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 143, 187–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. Education at a Glance 2020; OECD: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Goodson, P. Predictors of International Students’ Psychosocial Adjustment to Life in the United States: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2011, 35, 139–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clough, B.A.; Nazareth, S.M.; Day, J.J.; Casey, L.M. A Comparison of Mental Health Literacy, Attitudes, and Help-Seeking Intentions among Domestic and International Tertiary Students. Br. J. Guid. Couns. 2019, 47, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, A.; Boland, A.; Witt, K.; Robinson, J. Suicidal Behaviour, Including Ideation and Self-Harm, in Young Migrants: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.H.; Le, T.T.; Nguyen, H.K.T.; Ho, M.T.; Thanh Nguyen, H.T.; Vuong, Q.H. Alice in Suicideland: Exploring the Suicidal Ideation Mechanism through the Sense of Connectedness and Help-Seeking Behaviors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, A. Findings into Death of Nguyen Pham Dinh Le; Coroners Court Victoria: Southbank, Australia, 2021.

- Taliaferro, L.A.; Muehlenkamp, J.J.; Jeevanba, S.B. Factors Associated with Emotional Distress and Suicide Ideation among International College Students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2020, 68, 565–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckay, S.; Yuen, A.; Li, C.; Bailey, E.; Lamblin, M.; Robinson, J.; Bailey, E. Suicide Prevention for International Students: A Scoping Review Protocol. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e060266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated Methodological Guidance for the Conduct of Scoping Reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. Theory Pract. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.D.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.C.; Khalil, H. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, M.T.; Rajić, A.; Greig, J.D.; Sargeant, J.M.; Papadopoulos, A.; Mcewen, S.A. A Scoping Review of Scoping Reviews: Advancing the Approach and Enhancing the Consistency. Res. Synth. Methods 2014, 5, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covidence Systematic Review Software, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne. Australia. Available online: www.covidence.org (accessed on 4 July 2022).

- Kmet, L.M.; Cook, L.S.; Lee, R.C. Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers from a Variety of Fields; Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cerel, J.; Bolin, M.C.; Moore, M.M. Suicide Exposure, Awareness and Attitudes in College Students. Adv. Ment. Health 2013, 12, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Zarkar, S.; Tatum, J.; Rice, T.R. Asian International Students and Suicide in the United States. Asian J. Psychiatry 2020, 52, 102155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovchin, S. The Psychological Damages of Linguistic Racism and International Students in Australia. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 2020, 23, 804–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaslow, N.J.; Garcia-Williams, A.; Moffitt, L.; McLeod, M.; Zesiger, H.; Ammirati, R.; Berg, J.P.; McIntosh, B.J. Building and Maintaining an Effective Campus-Wide Coalition for Suicide Prevention. J. Coll. Stud. Psychother. 2012, 26, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, Y.S.; Bahr, S.; Chen, W.S. Moderators of Suicide Ideation in Asian International Students within a Single University Studying in Australia. Aust. Psychol. 2022, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Meilman, P.W.; Hall, T.M. Aftermath of Tragic Events: The Development and Use of Community Support Meetings on a University Campus. J. Am. Coll. Health 2006, 54, 382–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Rojas, A.E.; Choi, N.Y.; Yang, M.; Bartholomew, T.T.; Pérez, G.M. Suicidal Ideation Among International Students: The Role of Cultural, Academic, and Interpersonal Factors. Couns. Psychol. 2021, 49, 673–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servaty-Seib, H.L.; Lockman, J.; Shemwell, D.; Reid Marks, L. International and Domestic Students, Perceived Burdensomeness, Belongingness, and Suicidal Ideation. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 2016, 46, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.T.; Wong, Y.J.; Fu, C.C. Moderation Effects of Perfectionism and Discrimination on Interpersonal Factors and Suicide Ideation. J. Couns. Psychol. 2013, 60, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P.T.P. Suicide Risks among College Students from Diverse Cultural Backgrounds. Dir. Psychiatry 2013, 33, 237–249. [Google Scholar]

- Yeung, T.S.; Hyun, S.; Zhang, E.; Wong, F.; Stevens, C.; Liu, C.H.; Chen, J.A. Prevalence and Correlates of Mental Health Symptoms and Disorders among US International College Students. J Am. Coll. Health 2021, 70, 2470–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chau, W. Suicide in Australia: Submission to the Senate Inquiry Prepared by Wesa Chau Honorary President of Australian Federation of International Students; Australian Federation of International Students: Melbourne, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Council of International Students Australia. Council of International Student Australia’s Productivity Commission Recommendations; Council of International Students Australia: Melbourne, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- English Australia. The Guide to Best Practice in International Student Mental Health; English Australia: Surry Hills, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Haas, A.P.; Silverman, M.M.; Koestner, B. Saving Lives in New York: Suicide Prevention and Public Health. In Approaches and Special Populations; New York Office of Mental Health: New York, NY, USA, 2005; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson, A. Findings into Death of Zhikai Liu; Coroners Court Victoria: Southbank, Australia, 2019.

- Koo, C.S. Suicide in Asian American and Asian International College Students: Understanding Risk Factors, Protective Factors, and Implication for Mental Health Professionals. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Texas Austin, Austin, TX, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lento, R.M. Stratifying Suicide Risk among College Students: The Role of Ambivalence. Ph.D. Thesis, Catholic University of America, Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Maramaldi, P. Suicide: When an International Student Loses Hope. In Addressing Mental Health Issues Affecting International Students; Burak, P., Ed.; NAFSA Association of International Educators: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; pp. 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- McCauley, J. Report on Review of Suicide Prevention Protocols and Mental Health Policies and Procedures at Worcester Polytechnic Institute. 2022. Available online: https://www.wpi.edu/sites/default/files/Riverside-Trauma-Center-Review-of-WPI-Protocols.pdf (accessed on 4 July 2022).

- Orygen. International Students and Their Mental and Physical Safety; Orygen: Parkville, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Poole, R.; Robinson, C. Self-Harm and Suicide: Beyond Good Intentions. Univ. Coll. Couns. J. 2019, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Public Health England. Suicide Prevention: Identifying and Responding to Suicide Clusters; Public Health England: London, UK, 2019.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Prevention and Treatment of Anxiety, Depression, and Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors Among College Students; National Mental Health and Substance Use Policy Laboratory, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Rockville, MD, USA, 2021.

- Suicide Prevention Australia. Pre-Budget Submission January 2021; Mental Health Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Suicide Prevention Australia. Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) Populations Policy Position Statement December 2021; Suicide Prevention Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Suicide Prevention Resource Center. Promoting Mental Health and Preventing Suicide in College and University Settings; Suicide Prevention Resource Center: Newton, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- The Jed Foundation. Framework for Developing Institutional Protocols for the Acutely Distressed or Suicidal College Student; The Jed Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, Y. An Exploration of Asian International Students’ Mental Health: Comparisons to American Students and Other International Students in the United States. Ph.D. Thesis, Ohio University, Athens, OH, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Royal College of Pyschiatrists (RCPsy). Mental Health of Higher Education Students (CR231); Royal College of Pyschiatrists (RCPsy): London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Snowdon, J.; Choi, N.G. Undercounting of Suicides: Where Suicide Data Lie Hidden. Glob. Public Health 2020, 15, 1894–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilsen, J. Suicide and Youth: Risk Factors. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, G.; Milner, A.; McGill, K.; Pirkis, J.; Kapur, N.; Spittal, M.J. Predicting Suicidal Behaviours Using Clinical Instruments: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Positive Predictive Values for Risk Scales. Br. J. Psychiatry 2017, 210, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Self-Harm: Assessment, Management and Preventing Recurrence NICE Guideline; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, K.; Allan, S.; Beattie, L.; Bohan, J.; MacMahon, K.; Rasmussen, S. Sleep Problem, Suicide and Self-Harm in University Students: A Systematic Review. Sleep Med. Rev. 2019, 44, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowden, M.; McCoy, A.; Reavley, N. Suicidality and Suicide Prevention in Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) Communities: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Ment. Health 2020, 49, 293–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.; Bailey, E.; Witt, K.; Stefanac, N.; Milner, A.; Currier, D.; Pirkis, J.; Condron, P.; Hetrick, S. What Works in Youth Suicide Prevention? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. EClinicalMedicine 2018, 4–5, 52–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Universities Australia. Responding to Suicide: A Toolkit for Australian Universities; Universities Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Higher Education Mental Health Alliance (HEMHA). Project Postvention: A Guide for Response to Suicide on College Campuses; Higher Education Mental Health Alliance (HEMHA): New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Universities UK. Suicide-Safer Universities; Universities UK: London, UK, 2018; p. 36. [Google Scholar]

| Author(s) | Year | Country | Study Design | Study Aim | Sample | Main Findings for International Students | Suicide Prevention Recommendations | Future Research Recommendations | Quality Appraisal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cerel et al. [21] | 2013 | USA | Cross-sectional study | To determine experiences regarding suicide and those affected by it, and to determine students’ attitudes, perceptions, and behavioral intentions about suicide prevention resources | 117 college (9.3% international) students. Mage = 23.79, SD = 6.88. 36.8% male, 62.4% female, 0.8% unidentified. Demographics for international students not separately provided. Country of origin not specified. | International students less likely than domestic students to be aware of Lifeline (telephone support line for suicide) or see suicide as a problem | Campus resources should be directed towards international students to better engage them in services | Studies assessing effectiveness of targeted messaging for specific student groups, such as international students | 77.3% |

| Choi et al. [22] | 2020 | USA | Text and opinion | N/A | No participants. Editorial on Asian international students from the perspective of MDs treating this population | N/A | Medical practitioners require knowledge of acculturation processes Development of international-student-specific risk screening tools Medical practitioners should assess patient personality, utilize appropriate treatment modalities, and solution-focused approaches for suicidal ideation | Studies delineating impairment and suicide risk in international students | N/A |

| Clough et al. [8] | 2019 | Australia | Cross-sectional study | To examine potential differences in mental health and related constructs, such as mental health literacy and help-seeking attitudes, between domestic and international students in Australia | 209 international university students. Mage = 23.02, SD = 5.41. 37.5% male, 62.5% female. Country of origin not specified. 148 Domestic university students. Mage = 25.34, SD = 9.32. 19.1% male, 80.9% female | International students had lower mental health literacy, help seeking attitudes, and help seeking intentions for suicidal ideation than domestic students | Proactive interventions targeting mental health and help seeking for international students | Mixed methods or qualitative designs to facilitate insight into specific target areas for future mental health interventions for international students | 81.2% |

| Dovchin [23] | 2020 | Australia | Qualitative research | To illustrate how international students in Australia experience linguistic racism through ethnic accent bullying and linguistic stereotyping, and how the combination of this overall harmful experience may further cause psychological inferiority complexes, leading to mental health issues such as depression, suicidal ideation, and social anxiety disorder | Nine international university students. Mage = 23.55, SD = 3.78. 33.3% male, 66.7% female. Two participants from China, two from Mongolia, and one each from Vietnam, Somalia, Ukraine, Singapore, and Hong Kong | Experiences of linguistic racism (e.g., negative attitudes towards spoken accent or language pronunciation) reported to increase suicidal ideation by participants | Linguistic racism and associated bullying should be the target of suicide prevention programs Training of university personnel including mental health professionals on impacts of linguistic racism and bullying required | None provided | 65.0% |

| Hong et al. [1] | 2022 | USA | Case series | To examine variation in clinical characteristics, including suicidal ideation, suicide attempt history, and non-suicidal self-injury, across socio-demographic subgroups of students presenting for psychiatric emergency services | 725 college students (8% international students) visiting psychiatric emergency services. Mage = 22.00, SD = 3.97, 43.9% male, 56.7% female. Country of origin of international students not specified | International students were more likely to report lifetime history of multiple suicide attempts than domestic students International students were involuntarily admitted to the hospital a significantly higher percentage of the time than domestic students | Proactive screening and outreach efforts needed to reach international students and link them to services before crises emerge. | Studies of effective interventions are needed | 86.4% |

| Kaslow et al. [24] | 2012 | USA | Case study | To provide an example of an effective suicide prevention coalition | University staff and coalition members (unspecified number and no demographic information provided) who participated in the development of an effective campus wide coalition for suicide prevention | Effective coalitions targeting international students recruit and involve diverse community members in committees, including international students and those who have expertise in international student needs (e.g., international office, faculty from diverse backgrounds, international colleagues, and other relevant stakeholders) Development of language-specific communication materials (e.g., website and videos) for international students by international students supported creation of engaging materials for international student cohort | Include international students and those who work with them in development of suicide prevention activities, outreach programs, and any broader campus-based suicide prevention coalition activities | None provided | N/A |

| Low et al. [25] | 2022 | Australia | Cross-sectional study | To assess whether loneliness, campus connection, and problem-focused coping moderate the relationship between stressful life events and suicide ideation in Asian international students studying in Australia | 138 Asian international students Mage = 21.00, SD = 1.86, 32% male, 68% female. The origin country of participants was Singapore (44.2%), Malaysia (39.9%), Indonesia (8.7%), Hong Kong (3.6%), India (1.4%), Sri Lanka (0.7%) and Thailand (0.7%) | The relationship between stressful life events and suicidal ideation was moderated by lower levels of loneliness, higher levels of campus connectedness, and problem-focused coping | Suicide prevention efforts should address the issues of loneliness and lack of campus connectedness among international students. Activities aimed at promoting student cohesiveness on campus and peer support groups (e.g., camping trips, coffee clubs, or movie nights) at universities can be used to address such issues Increase awareness and skills related to problem-focused coping in international students. University counseling clinics could host workshops or promote such skills as part of their services | Qualitative data are required for future research to provide a rich and more accurate perspective of the experience of Asian international students living in Australia Further research needs to examine which of the key variables of campus connectedness, loneliness, or problem-focused coping are the most important for reducing the impact of stressful life events on suicidal ideation and how such relationships longitudinally impact suicidal ideation | 90.1% |

| Meilman and Hall [26] | 2006 | USA | Case study | To describe the development and successful implementation of campus postvention services in the aftermath of college student deaths by suicide, as well as by natural and accidental causes | Two university staff responsible for development of postvention approach at a single university | Postvention Community Support Meetings support students and staff to process tragedy of student deaths | Include international office in postvention planning and incident response | None provided | N/A |

| Nguyen et al. [10] | 2021 | Japan | Cross-sectional study | To explain how suicidal thoughts arise and persist inside one’s mind using a multifiltering information mechanism called Mindsponge | 268 university students (75.0% international, 25.0% domestic). Mage = 20.87, SD = not reported. 36.6% male, 63.4% female. The origin regions of the sample were Japan (25.8%), Southeast Asia (45.5%), East Asia (17.9%), South Asia (6.7%), and Other (4.1%) | Sense of connectedness and companionship reduces suicidal ideation less in international students than in domestic students Sense of connectedness and companionship increases informal help seeking, but this effect is reduced in international students Sense of connectedness and companionship decreases formal help seeking, and this effect is more pronounced in international students | Interventions should take a systematic and coordinated approach targeting different risk factors, including sense of belongingness, accessibility of help-seeking sources, and reducing improper cultural responses to mental health issues (e.g., stigma) | More studies using Mindsponge modeling techniques | 77.2% |

| Pérez-Rojas et al. [27] | 2021 | USA | Cross-sectional study | To examine the relationships among discrimination, cross-cultural loss, academic distress, thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, and suicidal ideation in international students | 595 international college students from two universities. Mage = 24.57, SD = 4.56. 51.5% male, 48.0% female, 0.5% other. The origin countries of the sample were India (34.8%), China (19.1%), Vietnam (3.4%), Malaysia (2.4%), Colombia (2.2%), Indonesia (2.0%), South Korea (2.0%), with the remainder coming from 67 other countries worldwide | Perceived burdensomeness predicted increased suicidal ideation Discrimination, cross-cultural loss, and academic distress positively predicted sense of burdensomeness, but only academic distress directly contributed to suicidal ideation when controlling for burdensomeness Thwarted belonginess did not predict suicidal ideation | Messaging from campus staff and university should be assessed to minimize risk of increasing sense of burdensomeness in international students Cultural competence and suicide prevention training should be provided to academic advisors so they can identify risks and refer international students to service Cultural competence training should be provided to clinicians to help recognize discrimination, cross-cultural loss, and academic distress as risk factors for suicide in international students | Longitudinal research to test temporality of effects with broader populations (e.g., international students from non-Asian countries) and measures (e.g., university specific belongness) Studies that separate out impact of pre-existing mental health issues compared to new or exacerbated issues related to moving to a new country | 90.1% |

| Servaty-Seib et al. [28] | 2015 | USA | Cross-sectional study | To assess the relationships between two types of belongingness (i.e., campus, family), perceived burdensomeness, and suicidal ideation in domestic and international students | 254 college students (46 international, 208 domestic). Mage = 21.1, SD = 1.8. 51.6% male, 48.4% female. The country of origin of the international students in the sample was China (8.2% of sample), India (3.5% of sample), and Malaysia (1.6% of sample), and Kenya (1.0% of sample) | Perceived burdensomeness predicted increased suicidal ideation in international and domestic students High family belonginess related to greater suicidal ideation in international students High campus belonginess related to lower suicidal ideation in international students Perceived discrimination not related to suicidal ideation | Clinicians should encourage international students to find ways to enhance and maintain connection with campus Collaboration between clinicians, international student office, and other support groups could be used to enhance students’ sense of connection with their campus Campus-based needs assessment could be used to guide actions to increase international student sense of belonging at their campus Training could be created to engage domestic students to better include international students and enhance campus connection | Studies assessing similar models with international students from other countries and universities Longitudinal studies to test temporality of effects over time and in different school years Qualitative studies assessing cultural differences across groups in perceptions of thwarted belongingness and burdensomeness | 81.2% |

| Taliaferro et al. [12] | 2020 | USA | Cross-sectional study | To assess the risk and protective factors that are associated with emotional distress and suicide ideation (i.e., strength and frequency of thoughts about killing one-self) among international college students | 334 international college students. Age range 18–26 years, 56% female. Race/ethnicity of the sample was Asian (62.0%), European (11.0%), Hispanic/Latino (9.3%), African (4.8%), Middle Eastern (4.8%), and Other (7.8%) | Higher entrapment, unmet interpersonal needs (thwarted belonginess and perceived burdensomeness), and ethnic discrimination associated with increased emotional distress Cultural stress, family conflict, perfectionism, ethnic discrimination, and unmet interpersonal needs positively related to suicidal ideation, but only unmet interpersonal needs related to greater suicidal ideation when controlling for other variables | Clinicians should consider entrapment, ethnic discrimination, and unmet interpersonal needs as risk factors for suicide Increase sense of campus belonging for international students Decrease sense of burdensomeness of international students by emphasizing value they bring Develop campaigns to reduce systematic and individual ethnic discrimination Cooperation between key university departments (e.g., international office, counselling center, academic affairs, etc.) to produce programming that supports students to feel a sense of belonging on campus | Longitudinal studies to assess temporality of effects that include additional variables such as coping strategies Qualitative studies to understand international student experiences and identify possible prevention and intervention approaches Assessment of macro-level factors such as cultural and institutional patterns, including host receptivity, pressure to conform, and the size of existing ethnic communities on campus | 77.3% |

| Wang et al. [29] | 2013 | USA | Cross-sectional study | To examine the moderating effects of three risk factors: perfectionistic personal discrepancy, perfectionistic family discrepancy, and discrimination on the associations between interpersonal risk factors (i.e., perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness) and suicide ideation | Asian international university students (N = 466). Mage = 26.39, SD = 4.99. 50.43% male, 49.57% female. The sample ethnic subgroups included China (52.8%), India (14.8%), Korea (8.4%), Vietnam (6.4%), Taiwan (4.5%), Thailand (2.8%), Sri Lanka (2.1%), Indonesia (1.5%), Japan (1.5%), Malaysia (1.1%), Nepal (1.1%), Philippines (0.9%), and five other smaller subgroups | Maladaptive perfectionism in the form of personal and family discrepancy (failing to meet standards or expectations) and discrimination positively related to suicidal ideation Family discrepancy and perceived discrimination intensified relationship between perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belonginess and suicidal ideation. | Clinicians should assess discrepancy between Asian international students’ family expectations and actual academic performance, and impact on suicidality Provide effective coping methods for any perceived discrepancy Those working with Asian international students should normalize stress and negative impact of cross-cultural transition process on academic performance, as maladaptive perfectionism may be heightened when transitioning into a new academic context Clinicians should help Asian international students understand racial dynamics in host country and externalize discrimination and self-blame | Studies assessing similar models in more diverse international student cohorts Longitudinal experimental research that facilitates greater causal understanding of effects Alternative measures of discrepancy (e.g., parent or sibling report) and ethnic discrimination (e.g., language discrimination) could facilitate a more nuanced understanding of impact of these variables on suicidality Qualitative studies could provide richer information on influence perfectionism and discrimination on suicide risk | 95.5% |

| Wong [30] | 2013 | USA and Canada | Text and opinion | N/A | No participants, review chapter on risk factors for suicide in diverse college students including international students | N/A | Culturally sensitive and community-based evidence-based interventions should be developed Cultural competency training should be provided to mental health professionals | Studies to determine efficacy of various approaches to suicide prevention | N/A |

| Yeung et al. [31] | 2021 | USA | Cross-sectional study | To assess the prevalence and correlates of mental health symptoms and diagnoses in international college students in the United States | 44,851 university students (2423 international, 42,428 domestic) International: 37.8% male, 59.3% female, 2.5% other. Country of origin not reported Domestic: 29.3% male, 67.8% female, 2.5% other | International students less likely than domestic students to report mental health diagnosis International students more likely than domestic students to report suicide attempts and feeling overwhelmingly depressed. | Increase awareness and improve psychoeducation on reducing stigma of mental health problems and understanding of warning signs for suicides in culturally sensitive manner Peer-based mental health awareness and referral training to reduce stigma and increase service engagement Engage parents in mental health to further support international students Translate psychoeducation materials and recruit more linguistically diverse clinicians to support students who prefer to interact in their own language | Qualitative research into subjective mental health experiences of international students Further research into mental health of non-Asian international students Mixed methods research to explore similarities and differences across cultural groups that can facilitate more nuanced approaches to addressing mental health issues | 81.8% |

| Authors | Year | Country | Document Type | Empirical Data or Findings | Suicide Prevention Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chau [32] | 2020 | Australia | Submission to government on suicide prevention | None | Compulsory for education providers to provide health services to international students Provide access to mental health services to international students Educate GPS to refer international students to appropriate mental health services Education for international students on mental health Mental health services to provide culturally appropriate services |

| Council of International Students Australia [33] | 2019 | Australia | Government Submission | None | Implement specific reporting framework/protocol for institutions in dealing with international students’ suicides to better track scope of problem |

| English Australia [34] | 2018 | Australia | Best practice guide | None | Staff training in mental health issues and risk factors for suicide in international students Colleges require clear protocols for crisis situations |

| Haas et al. [35] | 2005 | USA | Evidence based guide to Suicide prevention | None | Screening is an important strategy and should be targeted at risk groups, such as international students Promote sense of belonging for international students who may experience isolation through collaborative efforts between college staff across all organizational levels |

| Jamieson [36] | 2019 | Australia | Coroner’s Report | Design: Case Series Study Aim: To assess international student suicides between 2009 and 2015 in Australia Participants: 27 international students who died by suicide, with 24 from Asia, 2 from Americas, and 1 from Europe Results: Males aged 18–24 years (15 of 27), followed by males aged 25–29 years (5 of 27), were most common group. International students who died by suicide were less likely to have known history of self-harm, a mental health diagnosis, accessed services for mental health prior to suicide, or had a previously documented suicide attempt than domestic students who died by suicide. International students were more likely to experience educational or financial stressors, but less likely to experience death of a family member, conflict with a family member, exposure to family violence, or conflict with non-family acquaintances than domestic students before suicide. Most common stressor for international students before suicide was educational, with course failure and fear of telling parents particularly common. Similar proportions of students in the international and Australian-born cohorts gave indicators of intent before suicide; experienced interpersonal stressors such as separation from partner and conflict with partner prior to death; and experienced work-related stressors, social isolation, and substance misuse | Governments and education departments should work with relevant stakeholders to identify strategies to engage international students with mental health support Governments and education departments should work with relevant stakeholders to identify strategies to engage international students with mental health support Universities should provide reports of incidents within 4 weeks |

| Jamieson [11] | 2021 | Australia | Coroner’s Report | Design: Case Series Study Aim: To assess international student suicides between 2009 and 2019 in Australia Participants: 47 international students who died by suicide with 37 from Asia, 4 from Africa, 4 from the Americas, and 2 from Europe Results: Majority of suicides were male (70.2%) and under 24 years of age (63.8%). Most common stressors were educational (63.8%; e.g., course failure, course direction) and financial (32.6%). Intersecting stressors including homesickness and social isolation (22.4%) and parental expectations (14.3%) were commonly related to course failure and academic stress | Collaborations between university supports and external services including formal treatment pathway development Community engagement and linking as first point of support Training for students and providers in mental health access and barriers–potentially facilitated by insurers Counseling services to meet the language and cultural diversity needs of their international students |

| Koo [37] | 2010 | USA | Master’s thesis | None | Enhance counseling staff awareness of cultural attitudes to help seeking and mental health problems, and their own potential biases Create supportive and inclusive atmosphere at counseling centers to help students form connections in host country Counseling centers should take proactive approach to international students through organizing activities, workshops, and support groups |

| Lento [38] | 2016 | USA | Doctoral thesis | Design: Cohort study Aim: To investigate the role of ambivalence in the suicidal mind and its usefulness in stratifying risk among suicidal college students Participants: 226 university students (17% international students) attending university counseling center. Mage = 21.42, SD = 3.82. 44.2% male, 54.9% female, 0.8% other. Country of origin of international students not specified Results: International students more likely to withdraw from counseling or university prior to resolution of suicidal ideation than domestic students | Cultural competence training for mental health professionals to maintain international student engagement with services |

| Maramaldi [39] | 2019 | USA | Book chapter | None | Staff training to recognize suicide warning signs in international students Staff training on suicide risk assessment Encourage identification and reporting of suicide warning signs in students and staff Educational organizations should have a suicide protocol for if and when suicide occurs |

| McCauley [40] | 2022 | USA | Report of a review of suicide prevention protocols at educational institute | None | Suicide risk screening should be part of counseling intake process and provided in students’ native languages where possible Suicide prevention training should be provided to all incoming students, including international students |

| Orygen [41] | 2020 | Australia | Report | Collected data on international student mental health and physical safety but not specific to suicide | Provide gatekeeper training (e.g., Mental Health First Aid) to support staff and volunteers who work with vulnerable international students |

| Poole and Robinson [42] | 2019 | UK | Non-peer reviewed journal article—opinion piece | None | Student societies can be used to identify barriers and encourage help seeking in international student groups |

| Public Health England [43] | 2019 | UK | Practice resource | None | Postvention for clusters should include different relevant cultural groups. Recruitment may occur through international office |

| Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) [44] | 2021 | USA | Evidence-based resource guide for universities | None | Focused outreach efforts to increase knowledge of available mental health services should be targeted at international students Providers should refer non-native English speakers to services in their own language Where possible, mental health service providers should have same cultural background as student and interpreters can be used in the case of a language barrier |

| Suicide Prevention Australia [45] | 2021 | Australia | Submission to government on suicide prevention | None | Collaboration between governments, international student bodies, and local agencies should be used to roll out programs for international students |

| Suicide Prevention Australia [46] | 2021 | Australia | Policy position statement | None | Collaboration between government and organizations with expertise (e.g., lived experience, carers, and persons involved in family and international student support) in culturally appropriate service delivery to design, implement, and evaluate services |

| Suicide Prevention Resource Center [47] | 2004 | USA | White paper | None | Cultural competence training should be provided to mental health staff that identifies risks for international student mental health and suicide, including language issues, financial pressures, and culturally related mental health stigma |

| The JED Foundation [48] | 2006 | USA | Framework for developing institutional protocols for distress/suicide | None | Include international office in suicide prevention protocol development, implementation, use, and review Consider assessment barriers such as language and cultural differences Include translator where necessary to engage relevant parties |

| Xiong [49] | 2018 | USA | Doctoral thesis | Design: Case control study Aim: To investigate the mental health of Asian international students in the U.S. through a nationwide sample Sample: 10,731 university students with Asian international (n = 3702; 48% male, 51.2% female, 0.4% other, 0.4% missing), American (n = 3649; 48.4% male, 51.3% female, 0.4% other, 0.4% missing), and other international (n = 3380; 44.3% male, 55.4% female, 0.3% other) students. Country of origin not reported for international students Results: Proportion of Asian international students reporting self-injury, considering suicide, and dying by suicide was higher than in domestic and other international student groups. Asian international students sought less mental health services and were less willing to seek those services than American students and other international students | Mental health professionals and faculty members should be trained in predictors of poor mental health in international students Train staff who have regular contact with international students in their in mental health needs (e.g., residential assistants) Collaboration between student organizations and university services should be used to produce effective outreach programs or workshops that reduce mental health stigma |

| Cultural Competency Training on Suicide and Provision of Culturally Sensitive Services | Improved and Increased Risk Screening for Suicide | Proactive Intervention and Engagement Strategies | Collaborative Approaches to Streamline Service Access and Improve Available Support |

|---|---|---|---|

Target groups for training:

| Increased use of formal suicide risk screening measures:

| Targeted interventions:

| Collaboration between key services and groups with expertise:

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McKay, S.; Veresova, M.; Bailey, E.; Lamblin, M.; Robinson, J. Suicide Prevention for International Students: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1500. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021500

McKay S, Veresova M, Bailey E, Lamblin M, Robinson J. Suicide Prevention for International Students: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(2):1500. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021500

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcKay, Samuel, Maria Veresova, Eleanor Bailey, Michelle Lamblin, and Jo Robinson. 2023. "Suicide Prevention for International Students: A Scoping Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 2: 1500. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021500

APA StyleMcKay, S., Veresova, M., Bailey, E., Lamblin, M., & Robinson, J. (2023). Suicide Prevention for International Students: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 1500. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021500