How Work–Nonwork Conflict Affects Remote Workers’ General Health in China: A Self-Regulation Theory Perspective

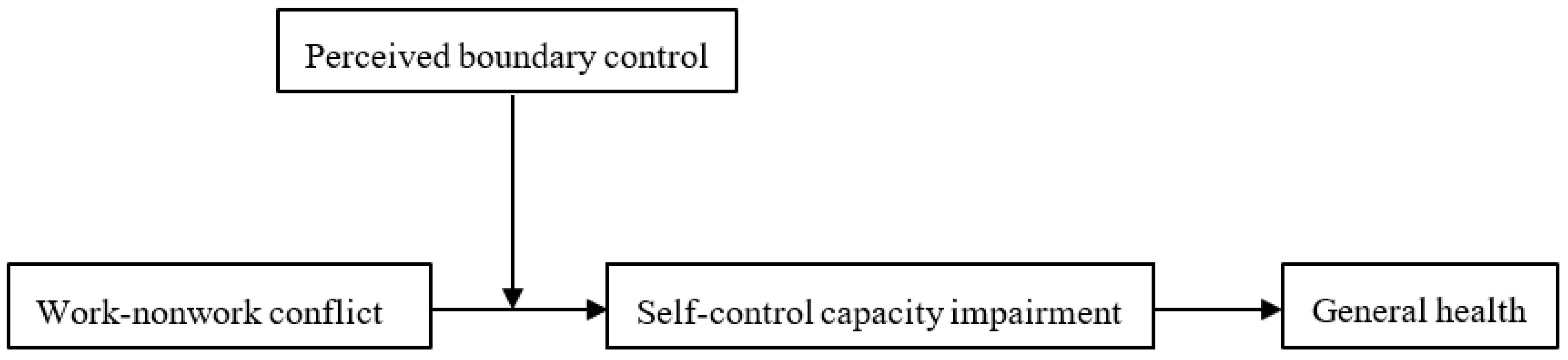

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Framework

1.2. Hypotheses

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

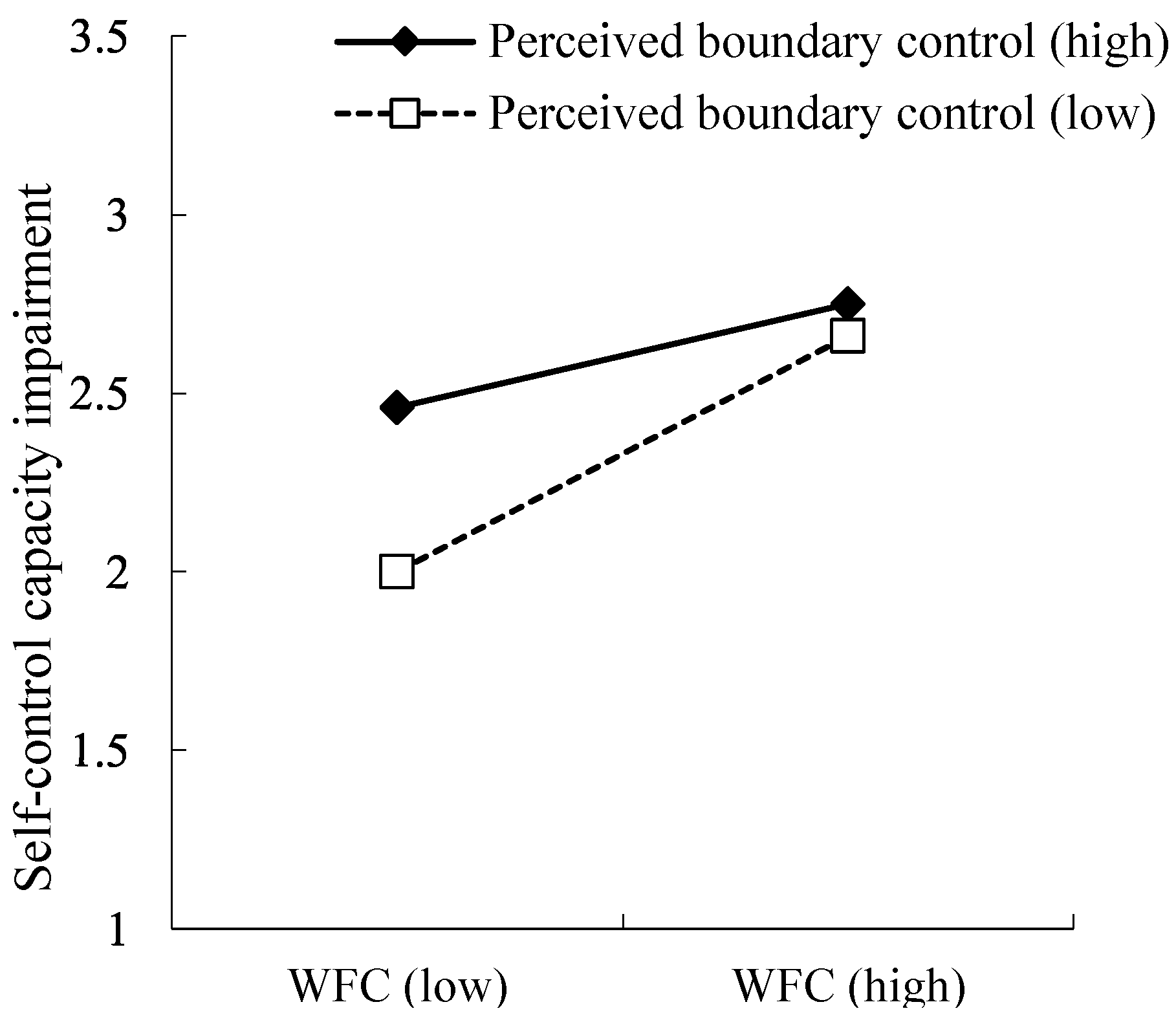

3.2. Hypothesis Testing

4. Discussion

4.1. Research Implications

4.2. Practical Implications

4.3. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Olson-Buchanan, J.B.; Boswell, W.R.; Morgan, T.J. The role of technology in managing the work and nonwork interface. In The Oxford Handbook of Work and Family; Allen, T.D., Eby, L.T., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 333–348. [Google Scholar]

- Miele, F.; Tirabeni, L. Digital technologies and power dynamics in the organization: A conceptual review of remote working and wearable technologies at work. Sociol. Compass. 2020, 14, e12795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emirza, S. Motivating remote workers during COVID-19 outbreak: Job demands-resources perspective. In Leadership after COVID-19; Dhiman, S.K., Marques, J.F., Eds.; Future of Business and Finance; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 377–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, P.; Rocha, J.V.; Moniz, M.; Gama, A.; Laires, P.A.; Pedro, A.R.; Dias, S.; Leite, A.; Nunes, C. Factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Vaccines 2021, 9, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molino, M.; Ingusci, E.; Signore, F.; Manuti, A.; Giancaspro, M.L.; Russo, V.; Zito, M.; Cortese, C.G. Wellbeing costs of technology use during Covid-19 remote working: An investigation using the Italian translation of the technostress creators scale. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhardt, J.; Recksiedler, C.; Linberg, A. Work from home and parenting: Examining the role of work—Family conflict and gender during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Soc. Issues. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaziri, H.; Casper, W.J.; Wayne, J.H.; Matthews, R.A. Changes to the work–family interface during the COVID-19 pandemic: Examining predictors and implications using latent transition analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 105, 1073–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desrochers, S.; Hilton, J.M.; Larwood, L. Preliminary validation of the work-family integration-blurring scale. J. Fam. Issues. 2005, 26, 442–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, M.; Kayser, I. The role of self-efficacy, work-related autonomy and work-family conflict on employee’s stress level during home-based remote work in Germany. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darouei, M.; Pluut, H. Work from home today for a better tomorrow! How working from home influences work—Family conflict and employees’ start of the next workday. Stress Health 2021, 37, 986–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huyghebaert-Zouaghi, T.; Morin, A.J.; Fernet, C.; Austin, S.; Gillet, N. Longitudinal profiles of work-family interface: Their individual and organizational predictors, personal and work outcomes, and implications for onsite and remote workers. J. Vocat. Behav. 2022, 134, 103695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barriga Medina, H.R.; Campoverde Aguirre, R.; Coello-Montecel, D.; Ochoa Pacheco, P.; Paredes-Aguirre, M.I. The influence of work–family conflict on burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic: The effect of teleworking overload. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnittker, J. When mental health becomes health: Age and the shifting meaning of self—Evaluations of general health. Milbank Q. 2005, 83, 397–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombardo, P.; Jones, W.; Wang, L.; Shen, X.; Goldner, E.M. The fundamental association between mental health and life satisfaction: Results from successive waves of a Canadian national survey. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossmeier, J.; Fabius, R.; Flynn, J.P.; Noeldner, S.P.; Fabius, D.; Goetzel, R.Z.; Anderson, D.R. Linking workplace health promotion best practices and organizational financial performance. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2016, 58, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muraven, M.; Baumeister, R.F. Self-regulation and depletion of limited resources: Does self-control resemble a muscle? Psychol. Bull. 2000, 126, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohu, E.A.; Spitzmueller, C.; Zhang, J.; Thomas, C.L.; Osezua, A.; Yu, J. When work–family conflict hits home: Parental work–family conflict and child health. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2019, 24, 590–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Vohs, K.D. Self—Regulation, ego depletion, and motivation. Soc. Personal. Psychol. 2007, 1, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossek, E.E.; Lautsch, B.A. Work–family boundary management styles in organizations: A cross-level model. Organ. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 2, 152–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossek, E.E.; Ruderman, M.N.; Braddy, P.W.; Hannum, K.M. Work–nonwork boundary management profiles: A person-centered approach. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 81, 112–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piszczek, M.M. Boundary control and controlled boundaries: Organizational expectations for technology use at the work–family interface. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 592–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beal, D.J.; Weiss, H.M.; Barros, E.; MacDermid, S.M. An episodic process model of affective influences on performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 1054–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmeichel, B.J.; Baumeister, R.F. Self-regulatory strength. In Handbook of Self-Regulation: Research, Theory, and Applications; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 84–98. [Google Scholar]

- Koopmann, J.; Wang, M.; Liu, Y.; Song, Y. Customer mistreatment: A review of conceptualizations and a multilevel theoretical model. Res. Occup. Stress Well Being 2015, 13, 33–79. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Beutell, N.J. Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1985, 10, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, S.C. Work/family border theory: A new theory of work/family balance. Hum. Relat. 2000, 53, 747–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; She, Z.; Zhou, Z.E.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, H. Job crafting and employee life satisfaction: A resource–gain–development perspective. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2022, 14, 1483–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.D.; Finkelstein, L.M. Work–family conflict among members of full-time dual-earner couples: An examination of family life stage, gender, and age. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2014, 19, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahm, P. The Effects of Work-Family Conflict and Enrichment on Self-Regulation and Social Networks. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2015; p. 10975. [Google Scholar]

- Demerouti, E.; Sanz-Vergel, A.I.; Petrou, P.; van den Heuvel, M. How work–self conflict/facilitation influences exhaustion and task performance: A three-wave study on the role of personal resources. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2016, 21, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanaj, K.; Johnson, R.E.; Barnes, C.M. Beginning the workday yet already depleted? Consequences of late-night smartphone use and sleep. Organ. Behav. Hum. Dec. 2014, 124, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Song, Y.; Koopmann, J.; Wang, M.; Chang, C.H.D.; Shi, J. Eating your feelings? Testing a model of employees’ work-related stressors, sleep quality, and unhealthy eating. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 1237–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tice, D.M.; Bratslavsky, E.; Baumeister, R.F. Emotional distress regulation takes precedence over impulse control: If you feel bad, do it! J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 80, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. The primacy of self-regulation in health promotion. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 2005, 54, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.S.; Wood, C.; Stiff, C.; Chatzisarantis, N.L. The strength model of self-regulation failure and health-related behaviour. Health Psychol. 2009, 3, 208–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.S. Sleep, self-regulation, self-control and health. Stress Health 2010, 26, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boals, A.; Vandellen, M.R.; Banks, J.B. The relationship between self-control and health: The mediating effect of avoidant coping. Psychol. Health 2011, 26, 1049–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlin, S.L.; Baer, R.A. Relationships between mindfulness, self-control, and psychological functioning. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2012, 52, 411–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nägel, I.J.; Sonnentag, S.; Kühnel, J. Motives matter: A diary study on the relationship between job stressors and exercise after work. Int. J. Stress. Manag. 2015, 22, 346–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hai, J.; Hong-Yu, M.; Ju-Lan, X.; Shu-Xia, Z. The effects of family-supported supervisor behavior on work attitudes: A moderated mediating model. J. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 5, 1194–1200. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Y.; Jex, S.M. Work-home boundary management using communication and information technology. Int. J. Stress. Manag. 2011, 18, 133–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Liu, Y.; Headrick, L. When work is wanted after hours: Testing weekly stress of information communication technology demands using boundary theory. J. Organ. Behav. 2020, 41, 518–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, C.M.; Simmering, M.J.; Atinc, G.; Atinc, Y.; Babin, B.J. Common methods variance detection in business research. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3192–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netemeyer, R.G.; Boles, J.S.; McMurrian, R. Development and validation of work–family conflict and family–work conflict scales. J. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 400–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E. Introducing the work–family-self balance: Validation of a new scale. In Proceedings of the III Community, Work and Family Conference, Utrecht, the Netherlands, 16 April 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Twenge, J.; Muraven, M.; Tice, D. Measuring State Self-Control: Reliability, Validity, and Correlations with Physical and Psychological Stress; San Diego State University: San Diego, CA, USA, 2004; Volume 93, pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, C.R.; Jomeen, J. Is the 12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) confounded by scoring method during pregnancy and following birth? J. Reprod Infant. Psychol. 2003, 21, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Lippe, T.; Lippényi, Z. Beyond formal access: Organizational context, working from home, and work–family conflict of men and women in European workplaces. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 151, 383–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Wang, Z.; Luo, Z. From supervisors’ work–family conflict to employees’ work–family conflict: The moderating role of employees’ organizational tenure. Int. J. Stress. Manag. 2020, 27, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press 2013, 51, 335–337. [Google Scholar]

- Twenge, J.M. A review of the empirical evidence on generational differences in work attitudes. J. Bus. Psychol. 2010, 25, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allard, K.; Haas, L.; Hwang, C.P. Family—Supportive organizational culture and fathers’ experiences of work–family conflict in Sweden. Gend. Work. Organ. 2011, 18, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zito, M.; Colombo, L.; Borgogni, L.; Callea, A.; Cenciotti, R.; Ingusci, E.; Cortese, C.G. The nature of job crafting: Positive and negative relations with job satisfaction and work-family conflict. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, K.A.; Dumani, S.; Allen, T.D.; Shockley, K.M. A meta-analysis of work–family conflict and social support. Psychol. Bull. 2018, 144, 284–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friese, M.; Frankenbach, J.; Job, V.; Loschelder, D.D. Does self-control training improve self-control? A meta-analysis. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2017, 12, 1077–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Kreiner, G.E.; Fugate, M. All in a day’s work: Boundaries and micro role transitions. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 472–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnentag, S.; Braun, I. Not always a sweet home: Family and job responsibilities constrain recovery processes. In New Frontiers in Work and Family Research; Grzywacz, J.G., Demerouti, E., Eds.; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2013; pp. 71–92. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, M.T. A two wave cross—Lagged study of work—Role conflict, work—Family conflict and emotional exhaustion. Scand. J. Psychol. 2016, 57, 591–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, M.T.; Knudsen, K. A two-wave cross-lagged study of business travel, work–family conflict, emotional exhaustion, and psychological health complaints. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2017, 26, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | — | |||||||

| 2. Job tenure | –0.06 | — | ||||||

| 3. Child under the age of 18 | –0.04 | –0.36 *** | — | |||||

| 4. Elder care | 0.07 | –0.34 *** | 0.43 ** | — | ||||

| 5. Work–nonwork conflict (T1) | –0.05 | –0.10 * | 0.06 | –0.09 | — | |||

| 6. Perceived boundary control (T1) | 0.03 | –0.06 | 0.04 | –0.05 | 0.41 *** | — | ||

| 7. Self-control capacity impairment (T2) | –0.05 | –0.07 | 0.01 | –0.09 * | 0.42 *** | –0.29 *** | — | |

| 8. General health (T2) | 0.09 | 0.10 * | –0.06 | 0.09 * | –0.44 *** | 0.38 *** | –0.55 ** | — |

| M | — | 6.54 | — | — | 2.61 | 2.53 | 2.42 | 3.02 |

| SD | — | 6.35 | — | — | 0.84 | 0.78 | 0.86 | 0.47 |

| Predictor | Self-Control Capacity Impairment (T2) | General Health (T2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equation (1) | Equation (2) | |||

| B | SE | B | SE | |

| Gender | –0.06 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.04 |

| Job tenure | –0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Children under the age of 18 | 0.02 | 0.09 | –0.05 | 0.04 |

| Elder care | –0.13 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.04 |

| Work–nonwork conflict (T1) | 0.41 *** | 0.04 | –0.14 *** | 0.02 |

| Self-control capacity impairment (T2) | –0.23 *** | 0.02 | ||

| R2 | 0.18 | 0.36 | ||

| F | 19.80 *** | 42.61 *** | ||

| Predictors | Self-Control Capacity Impairment (T2) | General Health (T2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equation (1) | Equation (2) | |||

| B | SE | B | SE | |

| Gender | –0.07 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.04 |

| Job tenure | –0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Children under the age of 18 | 0.01 | 0.08 | –0.05 | 0.04 |

| Elder care | –0.12 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.04 |

| Work–nonwork conflict (T1) | 0.34 *** | 0.06 | –0.14 *** | 0.04 |

| Self-control capacity impairment (T2) | –0.23 | 0.03 | ||

| Perceived boundary control (T1) | 0.17 ** | 0.06 | ||

| Work–nonwork conflict × perceived boundary control | –0.15 ** | 0.06 | ||

| R2 | 0.21 | 0.36 | ||

| F | 17.39 *** | 34.34 *** | ||

| Perceived Boundary Control | Effect | SE(boot) | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| −0.78 (M-SD) | −0.11 | 0.02 | [−0.15, −0.07] | |

| Self-control capacity impairment | 0 (M) | −0.08 | 0.02 | [−0.11, −0.05] |

| 0.78 (M+SD) | −0.05 | 0.02 | [−0.09, −0.02] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shi, Y.; Li, D.; Zhou, Z.E.; Zhang, H.; She, Z.; Yuan, X. How Work–Nonwork Conflict Affects Remote Workers’ General Health in China: A Self-Regulation Theory Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1337. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021337

Shi Y, Li D, Zhou ZE, Zhang H, She Z, Yuan X. How Work–Nonwork Conflict Affects Remote Workers’ General Health in China: A Self-Regulation Theory Perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(2):1337. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021337

Chicago/Turabian StyleShi, Yanwei, Dan Li, Zhiqing E. Zhou, Hui Zhang, Zhuang She, and Xi Yuan. 2023. "How Work–Nonwork Conflict Affects Remote Workers’ General Health in China: A Self-Regulation Theory Perspective" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 2: 1337. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021337

APA StyleShi, Y., Li, D., Zhou, Z. E., Zhang, H., She, Z., & Yuan, X. (2023). How Work–Nonwork Conflict Affects Remote Workers’ General Health in China: A Self-Regulation Theory Perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 1337. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021337