The 5-Minute Campus

Abstract

1. Introduction

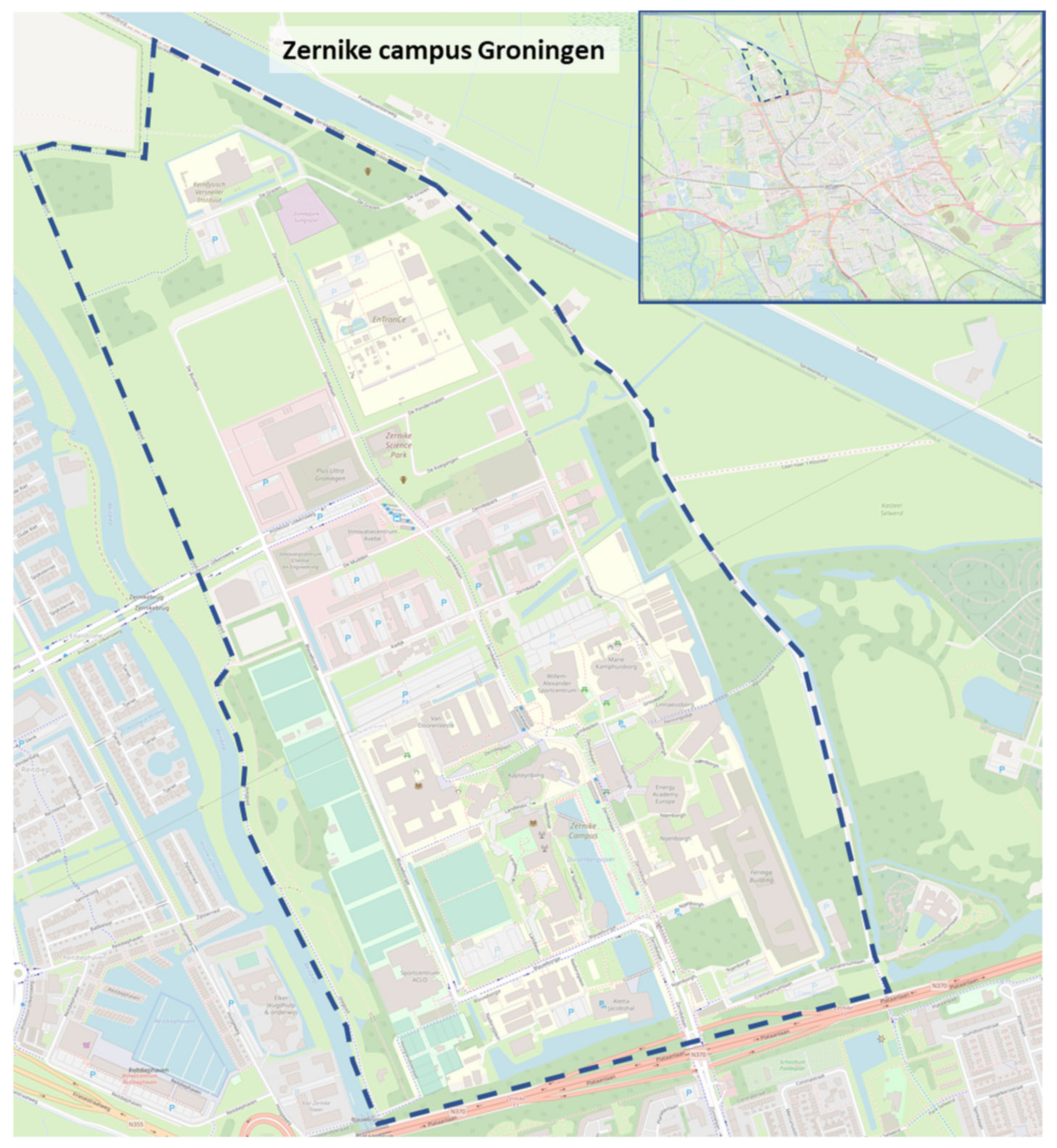

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Focus Group Protocol

2.3. Analysis

3. Results

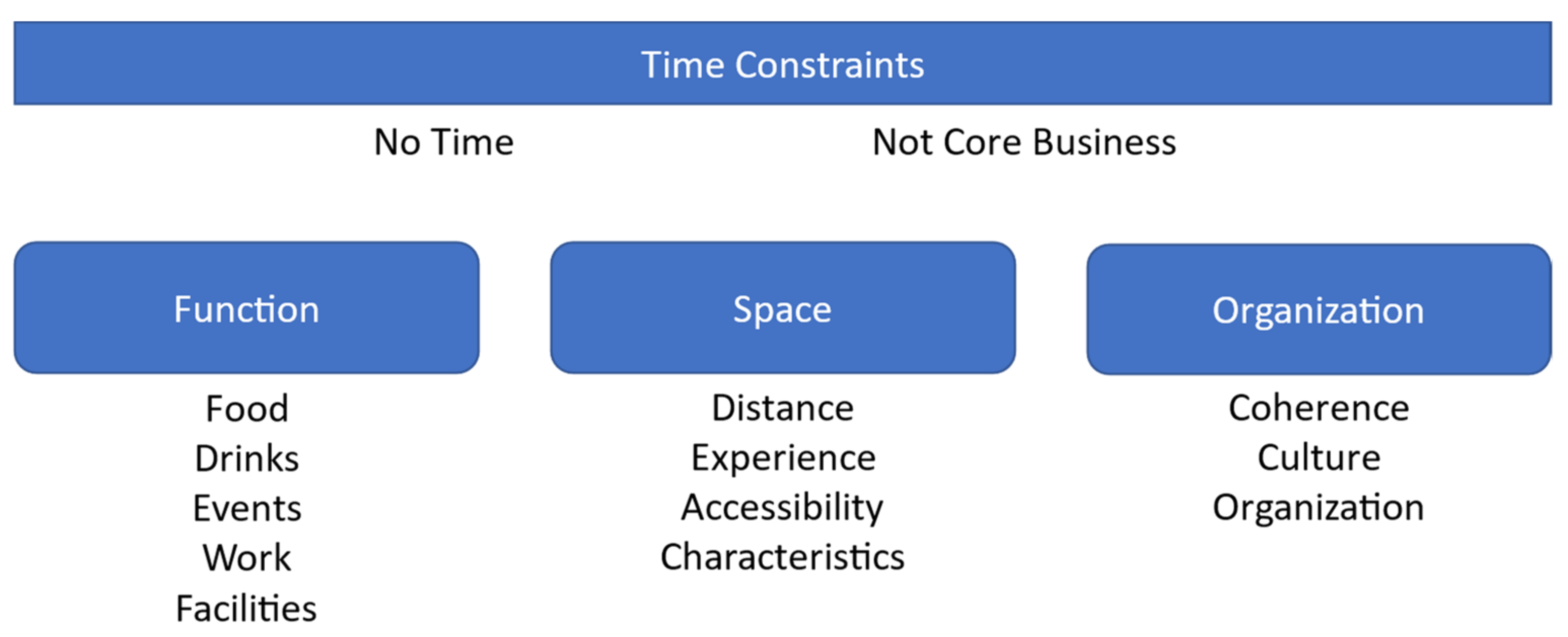

3.1. Time Constraints

“I feel that people are often running short on time. You don’t have much time to move around buildings which easily takes you 15 min. And many people don’t want to take the time, don’t have the time to do that. So the meetings happen around your actual workplace, the coffee machine, the copy machine, or on the way to your lunch break. So, it’s the proximity.” (R01)

“These movement activities [moving between buildings], they depend on purpose, on time of the day, and on proximity of the building to the office, because everything is related to limited time.” (R02)

“It’s not core business.” (R03)

“I don’t mind walking, but that’s not work.” (R04)

“I think it depends on how long the meeting or event will be. So, if you have an event or meeting for one hour, then you are not willing to walk 15 min. But if it’s … a 3- or 4-h session I don’t mind. So that is also, it should be a little bit in relation to the meeting.” (R05)

“I realized that when I started working on the 8th floor: ‘Oh, this takes basically quite some time, because you have to wait for the elevator and of course on the way back too.” (R03)

3.2. Function

You kind of need to pull people towards a place. That has a specific thing going on. Otherwise, they’re just out there walking the same square that they do for lunch every day, and then they go home. (R07)

And if you don’t have some attractor like that, then I would even say [you stay] only on your own floor or your own wing. Outside of that you never meet anyone. (R08)

The main reason [I meet people outside my own building] is food and coffee. It remains the main reason. Primary life necessity. (R07)

I would say the coffee and lunch is more for the smaller circle, for instance, unplanned meetings with colleagues or [other] people you know. And [when you meet at an event] it is an unplanned meeting with a larger circle, so people you don’t know yet or people you don’t regularly meet. (R08)

[In the north of the campus, where most companies are located] there is not much to experience in the form of a canteen or places where you can sit. Or can mingle with other people. Because that is a bit further back on campus. So, to walk to the food court, you could do that. But it is a long way. You could. But you don’t. (R03)

You go there because there are facilities that all people and companies on the campus can use. Like a conference center, or lunch facilities, or the coffee bar, or a real bar … things like that. I mean something useful or nice that you use during or at the end of your working day. And then it starts to live then, that’s where you meet people. (R08)

I regularly skip meetings or events because I think I cannot learn something from it, or I cannot bring in my knowledge in a proper way. (R06)

When there’s an event you are already with people that have some kind of same interest, then it is easier to start a conversation. Sometimes when I go for lunch or for coffee, you’re a little bit … You go, you take it, and you leave, you know. (R12)

If you go to an event, you are sure you will meet other people. And you’re also a bit open to it because you are ready to meet other people. That’s usually the reason to go to an event also. (R13)

It’s events from [the staff association] that organizes events, and these kinds of activities that you attend. And there, spontaneous interactions happen. (R01)

There’s no space to kind of carry these types of activities. There’s is no restaurant or organization that has a stage. On the campus to do any of this. … There is no place to book a room, to have a drink with your department or company to celebrate something. So, what this campus misses entirely is celebrations. There is nothing there to support that. (R07)

As I said before, I used to go for lunch at the food court because it has the facilities. If there are facilities around which attract me, then I’ll go there. (R10)

3.3. Space

We would love to have the situation where a Ph.D. student, by accident, bumps into someone from a company. And they talk about and ‘hey, are you doing this, are you doing that?’ But that is virtually absent as far as I know. Because the distances are big and of course you can’t chance that really. The physical distances. But also, because these facilities are a bit spread out and a bit small and not so handy often. (R03)

Of course, I tried to find the place that is kind of attractive then. So, you have a nice coffee corner or perhaps we can sit outside. (R06)

It’s hidden! Don’t hide it, pull it out into the open! Cause that’s a problem, right? If you don’t put it out into the open, then it’s not there. Basically. (R07)

If I understand correctly, more seating will be installed around the pond. Then you would get such a traffic area of meeting places there. (R09)

3.4. Organization

[This is] all very focused on the buildings, while I think the communities and the people should be much more central. In addition, then the buildings will support that. (R11)

If you have a company that just produces e.g., cookies, it’s not very interesting for them to have, or to develop, their knowledge base as strong as companies that are focused on innovation. And these companies that are actually interested in innovations, they are here for a reason, on the campus. Because you have this connection close to research [with] a similar focus. Whereas companies that don’t really search for this innovation, they probably settle somewhere else. (R08)

A lot of my collaborations started at bars, after work, in conferences. But here usually… it’s also part of the Dutch culture just to go home after work. And then maybe you’ll meet friends afterwards. (R10)

Several universities are working on it and yet, are struggling with it. To arrange that properly, efficiently. On the one hand, you don’t want to have too little space, but on the other hand, you don’t want it to sit empty either. Because that just costs money. So, it’s understandable that it’s always a bit of a squeeze on all sides. (R03)

3.5. A Comparison of Findings

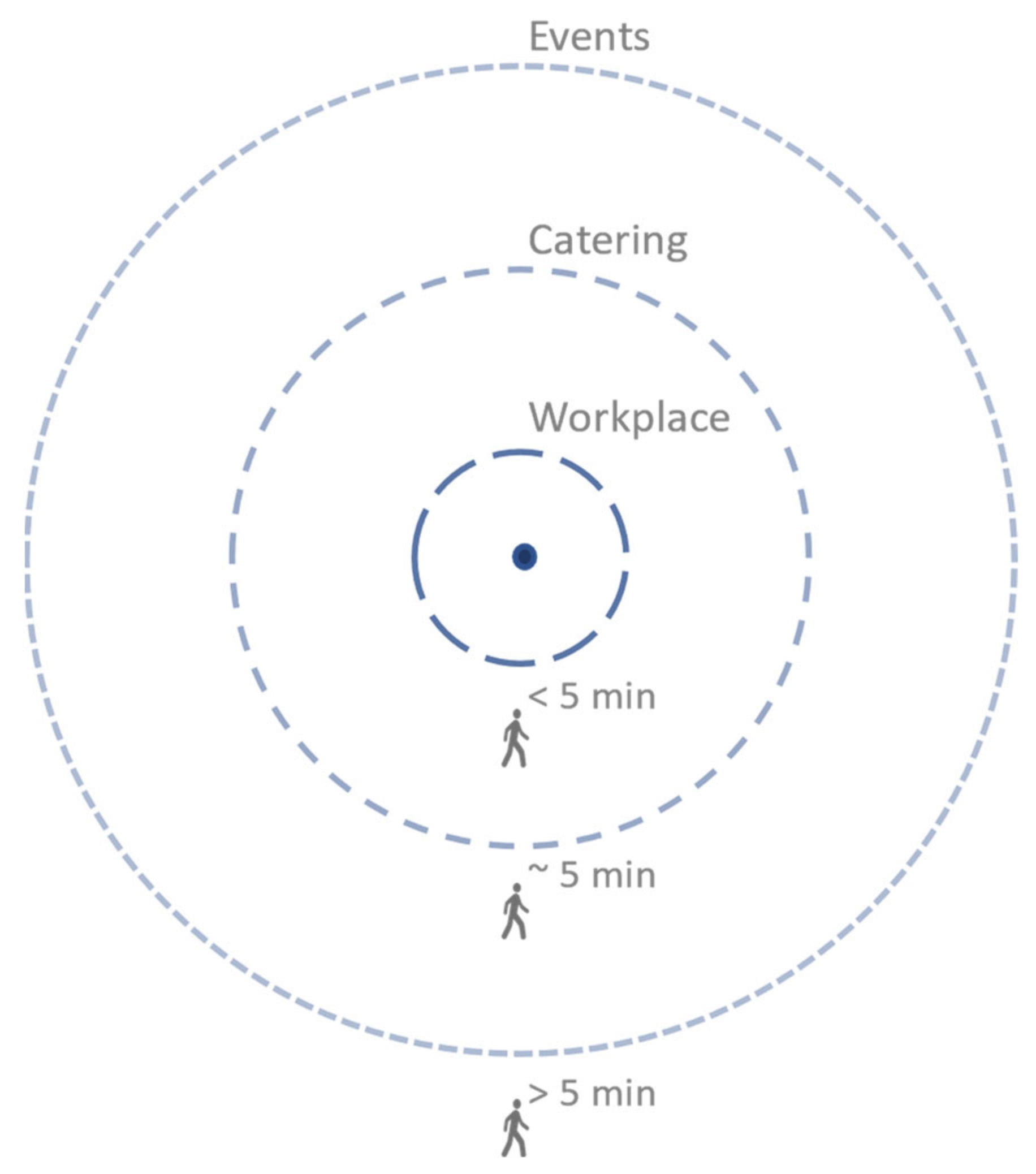

3.6. The 5-Minute Campus

4. Discussion

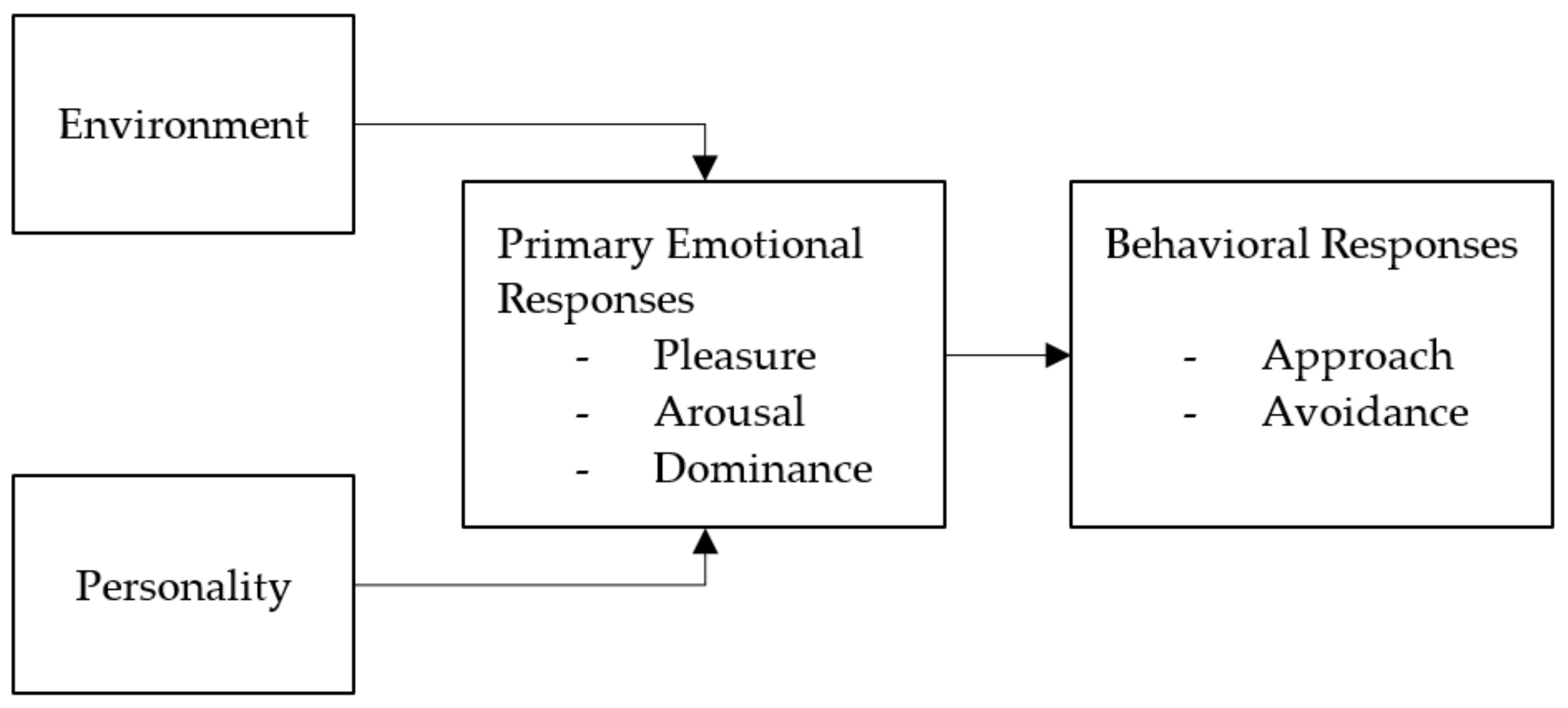

4.1. Motivators and Constraints

4.2. The 5-Minute Campus

4.3. Practical Relevance

4.4. Strenghts and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- VSNU. Een Raamwerk Valorisatie-Indicatoren; VSNU: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Etzkowitz, H. The Triple Helix: University-Industry-Government Innovation in Action; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Buck Consultants International. Inventarisatie en Analyse Campussen 2014; Buck Consultants International: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- TU Delft. Valorisatieagenda TU Delft 2020; TU Delft: Delft, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- VU Amsterdam. VU Instellingsplan 2015–2020; VU Amsterdam: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jansz, S.; van Dijk, T.; Mobach, M. Critical success factors for campus interaction spaces and services—A literature review. J. Facil. Manag. 2020, 18, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Geenhuizen, M. Valorisation of knowledge: Preliminary results on valorisation paths and obstacles in bringing university knowledge to market. In Proceedings of the 18th Annual High Technology Small Firms Conference, Enschede, The Netherlands, 25–28 May 2010; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Innovatieplatform. Valorisatieagenda: Kennis Moet Circuleren; Innovatieplatform: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dinteren, J.; Jansen, P.; Lettink, N. Ruimte voor kennisontwikkeling—Van sciencepark tot innovatiedistrict. M&O 2017, 3, 65–82. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, C.; Allam, Z.; Chabaud, D.; Gall, C.; Pratlong, F. Introducing the ‘15-minute city’: Sustainability, resilience and place identity in future post-pandemic cities. Smart Cities 2021, 4, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, D.C.; King, D.A.; Lemar, S. Accessibility in practice: 20-minute city as a sustainability planning goal. Sustainability 2020, 12, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, T.M.; Hobbs, M.H.; Conrow, L.C.; Reid, N.L.; Young, R.A.; Anderson, M.J. The x-minute city: Measuring the 10, 15, 20-minute city and an evaluation of its use for sustainable urban design. Cities 2022, 131, 103924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staricco, L. 15-, 10- or 5-minute city? A focus on accessibility to services in Turin, Italy. J. Urban Mobil. 2022, 2, 100030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, S.; Hardwick, C. The ‘Five Minute City’: A New Way to Imagine a Better Vancouver|The Tyee. 2018. Available online: https://thetyee.ca/Opinion/2018/10/17/Five-Minute-City-Better-Vancouver/ (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Brown, M.G. Proximity and collaboration: Measuring workplace configuration. J. Corp. Real Estate 2008, 10, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appel-Meulenbroek, R.; de Vries, B.; Weggeman, M. Knowledge Sharing Behavior: The Role of Spatial Design in Buildings. Environ. Behav. 2017, 49, 874–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M.S. The Strength of Weak Ties. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 78, 1360–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Andel, P. Anatomy of the unsought finding. Serendipity: Orgin, history, domains, traditions, appearances, patterns and programmability. Br. J. Philos. Sci. 1994, 45, 631–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peponis, J.; Bafna, S.; Bajaj, R.; Bromberg, J.; Congdon, C.; Rashid, M.; Warmels, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zimring, C. Designing space to support knowledge work. Environ. Behav. 2007, 39, 815–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björneborn, L. Three key affordances for serendipity: Toward a framework connecting environmental and personal factors in serendipitous encounters. J. Doc. 2017, 73, 1053–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayard, A.L.; Weeks, J. Photocopiers and water-coolers: The affordances of informal interaction. Organ. Stud. 2007, 28, 605–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, J.J. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the Gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghimehfar, F.; Halpenny, E.A. How do people negotiate through their constraints to engage in pro-environmental behavior? A study of front-country campers in Alberta, Canada. Tour. Manag. 2016, 57, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R. The Dragons of Inaction: Psychological Barriers that Limit Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, E.L.; Crawford, D.W.; Godbey, G. Negotiation of leisure constraints. Leis. Sci. 1993, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbard, J.; Mannell, R.C. Testing competing models of the leisure constraint negotiation process in a corporate employee recreation setting. Leis. Sci. 2001, 23, 145–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, J.S.; Mowen, A.J.; Kerstetter, D.L. Testing Alternative Leisure Constraint Negotiation Models: An Extension of Hubbard and Mannell’s Study. Leis. Sci. 2008, 30, 198–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, C.; Hardy, J.H.; Buckley, M.R. Understanding the role of networking in organizations. Career Dev. Int. 2014, 19, 146–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansz, S.N.; Mobach, M.; van Dijk, T.; de Vries, E.; van Hout, R. On Serendipitous Campus Meetings: A User Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennink, M.; Hutter, I.; Bailey, A. Qualitative Research Methods, 2nd ed.; SAGE: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J. Interviews, Focus groups and Delphi techniques. In Advanced Research Methods for Applied Psychology: Design, Analysis and Reporting; Brough, P., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 95–106. [Google Scholar]

- Rowley, J. Conducting research interviews. Manag. Res. Rev. 2012, 35, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, M. Qualitative research methods: Why, when, and how to conduct interviews and focus groups in pharmacy research. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2016, 8, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RUG.nl. University of Groningen. 2022. Available online: https://www.rug.nl/ (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- OpenStreetMap, AND Data—OpenStreetMap Wiki. 2022. Available online: https://wiki.openstreetmap.org/wiki/AND_data (accessed on 13 December 2022).

- Campus Groningen. Zernike Campus Groningen. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/campusgr/photos/a.757735701055178/1825539004274837 (accessed on 16 December 2022).

- Galletta, A. Mastering the Semi-Structured Interview and Beyond, 1st ed.; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Friese, S. Qualitative Data Analysis with ATLAS.ti; SAGE: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drennan, D. Transforming Company Culture; McGraw-Hill: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, D.; Luo, Q. Knowledge diffusion at business events: The mechanism. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 71, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaap, N.; Harms, L.; Kansen, M.; Wüst, H. Cycling and Walking: The Grease in Our Mobility Chain (No. KiM-16-A03). 2016. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/311773579_Cycling_and_walking_the_grease_in_our_mobility_chain (accessed on 9 December 2022).

| Focus Group | Knowledge Institution | Company |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 0 |

| 2 | 5 | 1 |

| 3 | 2 | 3 |

| 4 | 1 | 3 |

| 5 | 0 | 4 |

| Total | 11 | 11 |

| Survey Results | Focus Group Propositions | Additional Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Buildings with a low score did not seem to host fewer meetings. Often these meetings came from within the same building. | ‘Even if the quality of the building where I work is low, I still prefer to stay here for interactions.’ | Strong emphasis on time constraints. E.g., a long travel time within their own building is a barrier to visiting other locations. |

| Movement between buildings with a similar theme (e.g., energy). | ‘The only reason to move to a different building is if there are people there with specific knowledge I need (e.g., companies or special expertise).’ | People will not visit a building just because it has a (related) theme. An event or planned meeting is necessary for people to feel invited to visit. However, with a clear and attractive function (themed or not) will attract people to a certain location. |

| Coffee and lunch were important services | ‘When I go somewhere for coffee or lunch, it is one of the main moments in which I have unexpected meetings.’ | This is mostly true for unexpected meetings with people participants are already familiar with, but not likely for completely new contacts. There is a cultural barrier to start a conversation with a complete stranger (about work) when it is not framed by an event, planned meeting, or introduction by an acquainted co-worker. |

| Events and meetings were indicated as important services | ‘The main reason I meet people outside my building is for an event or meeting.’ | This was a strong attractor and culturally appropriate setting to start new conversations. There is a need for campus management to be involved in organizing these events, to create a lively campus. Spaces and facilities to support this also have to be made available. |

| Outdoor spaces were largely missing from the survey results, but were emphasized in the focus groups as important spaces for unplanned meetings. |

| Natural Moment | Travel Time | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Short break | <5 min | Coffee, toilet |

| Lunch break | Approx. min | Food court, restaurant |

| Meeting | >5 min 1 | Event, planned meeting |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jansz, S.N.; Mobach, M.; van Dijk, T. The 5-Minute Campus. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1274. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021274

Jansz SN, Mobach M, van Dijk T. The 5-Minute Campus. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(2):1274. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021274

Chicago/Turabian StyleJansz, Sascha Naomi, Mark Mobach, and Terry van Dijk. 2023. "The 5-Minute Campus" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 2: 1274. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021274

APA StyleJansz, S. N., Mobach, M., & van Dijk, T. (2023). The 5-Minute Campus. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 1274. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021274