The Effect of Work Stress on the Well-Being of Primary and Secondary School Teachers in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Work Stress and the Well-Being of Primary and Secondary School Teachers

1.2. Family–Work Conflict as a Mediator

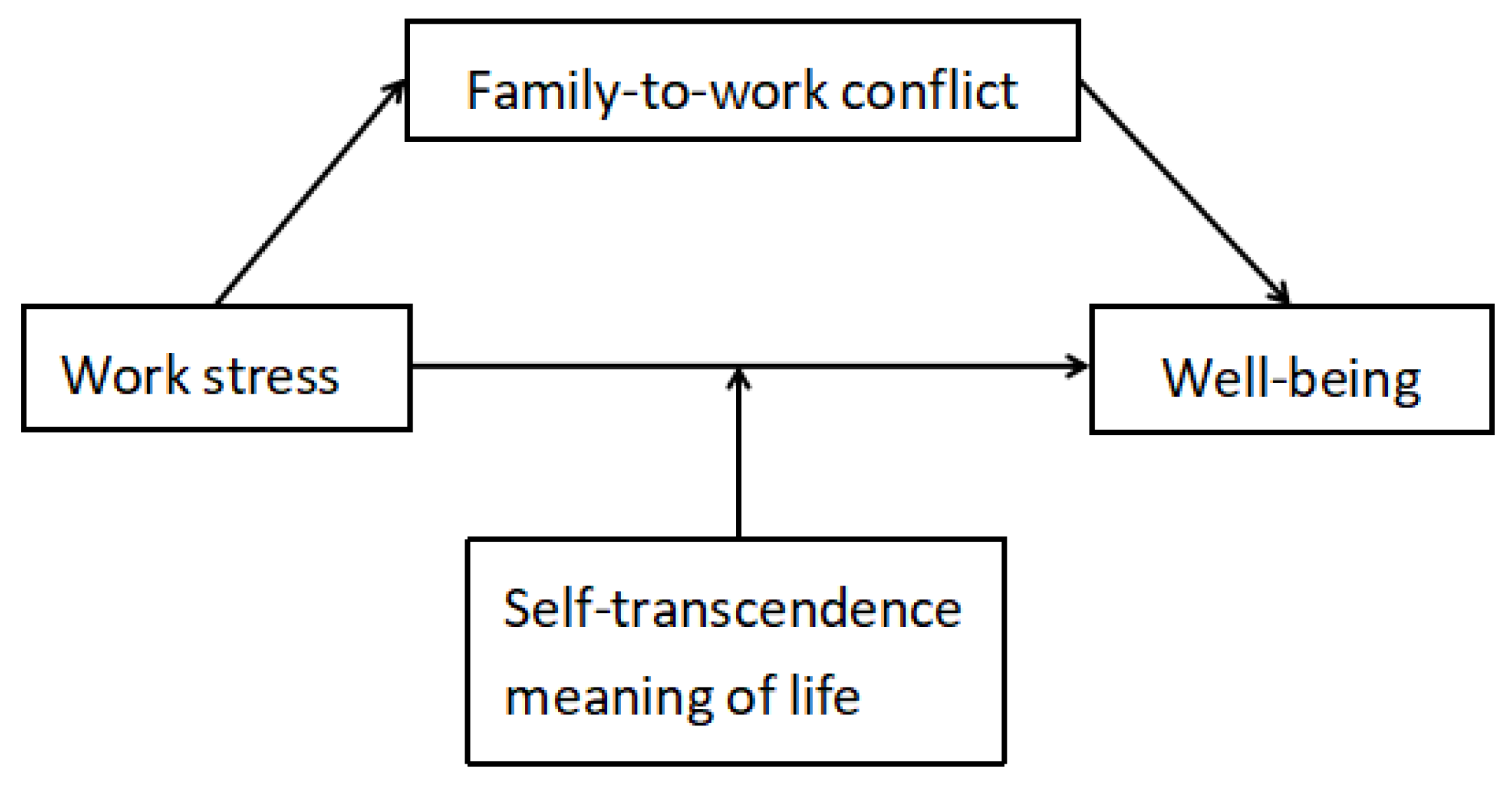

1.3. Self-Transcendent Meaning of Life as a Moderator

1.4. The Present Study

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Work Stress

2.2.2. Work–Family Conflict

2.2.3. Well-Being

2.2.4. Self-Transcendent Meaning of Life

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Common Method Bias

3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Difference Analysis

3.3. Mediating Effect of Family–Work Conflict

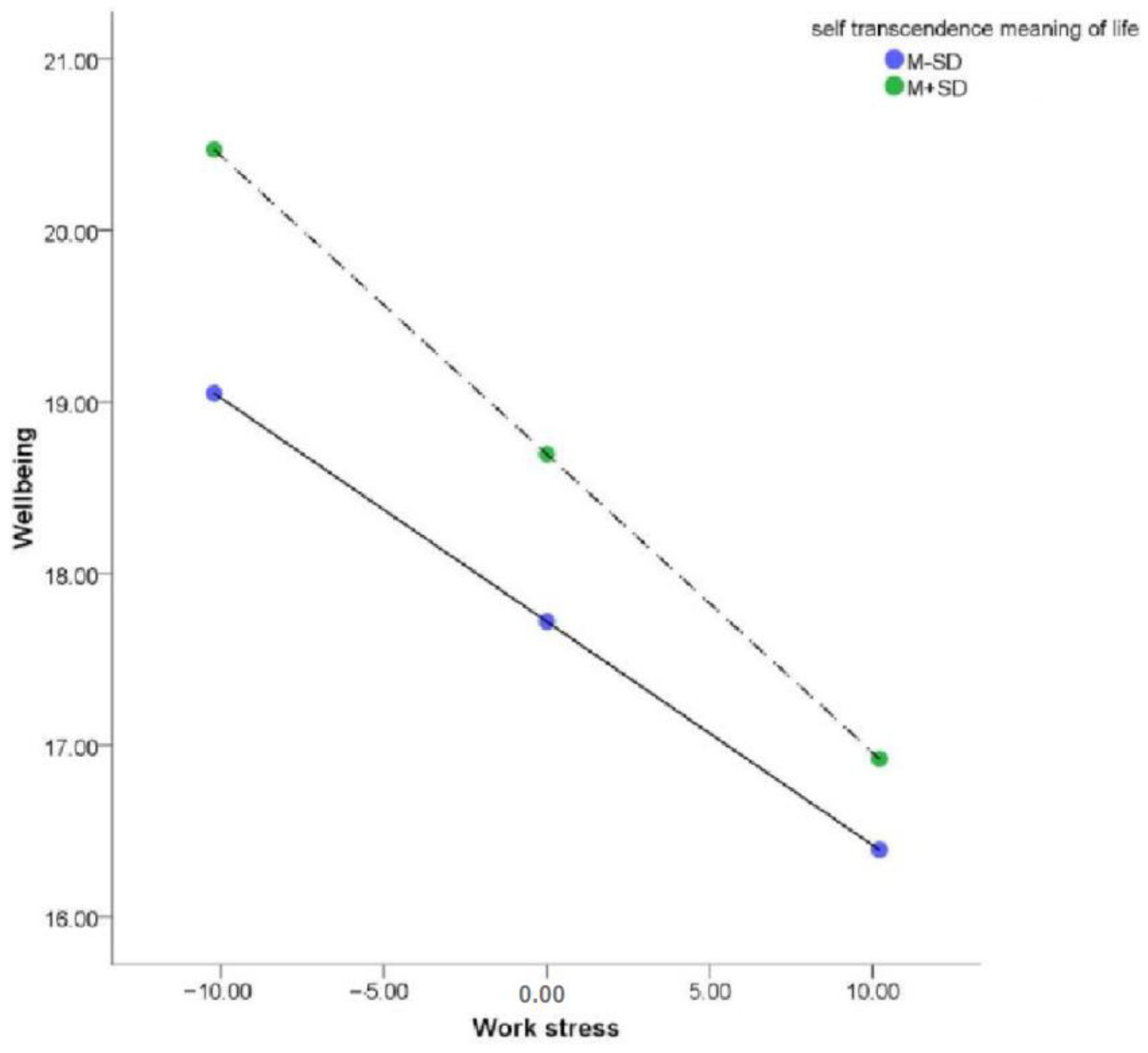

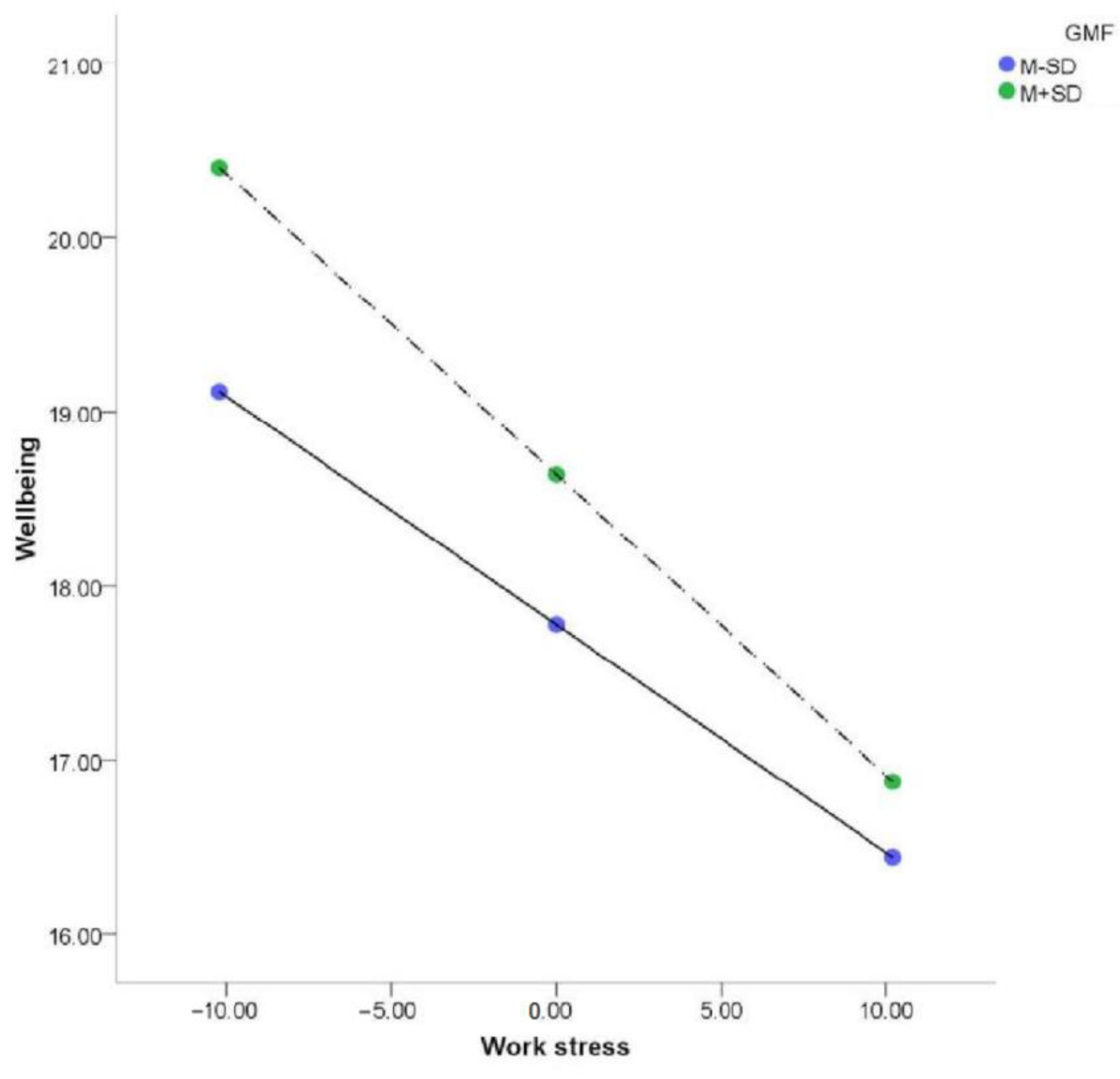

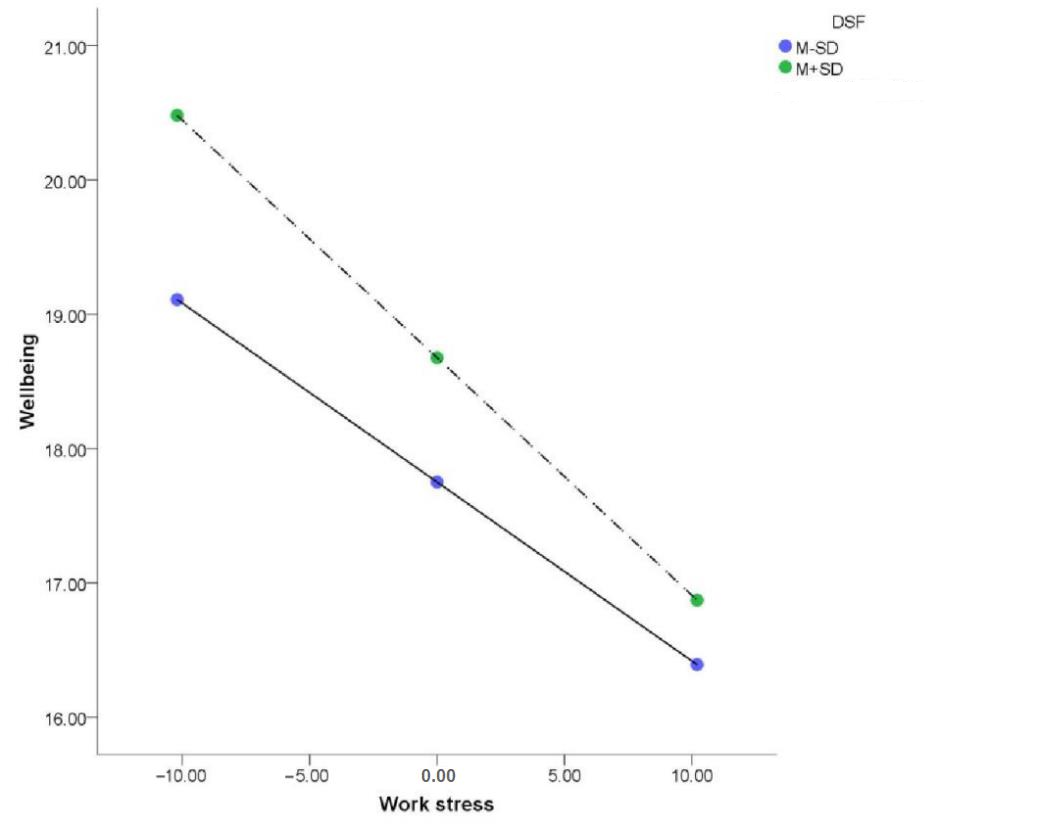

3.4. Moderating Effects of the Self-Transcendent Meaning of Life, GMF, and DSF

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications

4.2. Limitations and Prospects

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dubovyk, O.M.; Dubovyk, V.Y. Health of the teacher of higher education institutions (efficiency-development). Wiadomości Lek. 2021, 74, 773–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.M.; Li, L.; Zhou, B.; Liao, J. Mental health of primary and secondary teachers in Yunnan province. China J. Health Psychol. 2015, 23, 201–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Droogenbroeck, F.; Spruyt, B. Do teachers have worse mental health? Review of the existing comparative research and results from the Belgian Health Interview Survey. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2015, 51, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicke, T.; Stebner, F.; Linninger, C.; Kunter, M.; Leutner, D. A longitudinal study of teachers’ occupational well-being: Applying the job demands-resources model. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2018, 23, 262–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronsson, G.; Theorell, T.; Grape, T.; Hammarström, A.; Hogstedt, C.; Marteinsdottir, I.; Skoog, I.; Träskman-Bendz, L.; Hall, C. A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and burnout symptoms. J. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, R.; Moed, A.; Shoshani, A.; Roth, G.; Kanat-Maymon, Y. Teachers’ conditional regard and students’ need satisfaction and agentic engagement: A multilevel motivation mediation model. J. Youth Adolesc. 2020, 49, 790–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, K.A.; Dumani, S.; Allen, T.D.; Shockley, K.M. A meta-analysis of work-family conflict and social support. Psychol. Bull. 2018, 144, 284–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurung, R.A.R. Health psychology: A cultural approach. In Health Psychology A Cultural Approach; Wadsworth/Cengage Learning: Belmont, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Garrick, A.; Mak, A.S.; Cathcart, S.; Winwood, P.C.; Bakker, A.B.; Lushington, K. Non-work time activities predicting teachers’ work-related fatigue and engagement: An effort-recovery approach. Aust. Psychol. 2018, 53, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stansfeld, S.; Candy, B. Psychosocial work environment and mental health--a meta-analytic review. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2006, 32, 443–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 50, 337–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghieh, A.; Montgomery, P.; Bonell, C.P.; Thompson, M.; Aber, J.L. Organisational interventions for improving wellbeing and reducing work-related stress in teachers. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, CD010306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. Review and prospect of research on mental health status of middle school teachers. J. Hubei Univ. Educ. 2006, 23, 75–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meulenbroek, L.F.; van Opstal, M.J.; Claes, L.; Marres, H.A.; de Jong, F.I. The impact of the voice in relation to psychosomatic well-being after education in female student teachers: A longitudinal, descriptive study. J. Psychosom. Res. 2012, 72, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Q.; Liao, J.Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, D.J.; Liu, M.F. Validity and reliability of the Chinese version of the Short well-being Scale in Chinese adults. Chin. Ment. Health J. 2021, 35, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atashpanjeh, A.; Shekarzehi, S.; Zare-Behtash, E.; Ranjbaran, F. Burnout and job dissatisfaction as negative psychological barriers in school settings: A mixed-methods investigation of Iranian teachers. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2020, 9, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, J. Sources of and conflict family between work and family roles. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1985, 10, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, M.; Falci, C.D. A demands and resources approach to understanding faculty turnover intentions due to work-family balance. J. Fam. Issues 2016, 37, 393–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frone, M.R.; Russell, M.; Cooper, M.L. Antecedents and out-comes of work-family conflict: Testing a model of the work-familyinterface. J. Appl. Psychol. 1992, 77, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, H.L.; Zhang, H.Y. A Review of Researches on Work-family Conflict. J. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 29, 124–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.X.; Zhang, D.J.; Yu, L.; Guo, C.; Chen, X. Analysis and suggestions on the characteristics of work-family conflicts among primary and secondary school teachers. J. Southwest Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2010, 36, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Y.; Chen, W.J. Relationship between job-family relationship and personality: Moderating effect on job embeddedness and family intimacy. Chin. Pers. Sci. 2022, 3, 60–72. [Google Scholar]

- Aulén, A.-M.; Pakarinen, E.; Feldt, T.; Tolvanen, A.; Lerkkanen, M.-K. Psychological detachment as a mediator between successive days’ job stress and negative affect of teachers. Front. Educ. 2022, 7, 903606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Steenbergen, E.F.; Kluwer, E.S.; Karney, B.R. Work-family enrichment, work-family conflict, and marital satisfaction: A dyadic analysis. J. Ofoccupational. Health Psychol. 2014, 19, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Lin, X.; Zhang, F.; Tian, Y. Playing roles in work and family: Effects of work/family conflicts on job and life satisfaction among junior high school teachers. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 772025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorensen, T.J.; Mckim, A.J.; Velez, J.J. A national study of work characteristics and work- family conflict among secondary agricultural educators. Dep. Agric. Ext. Educ. 2017, 58, 214–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. Self-transcendence meaning of life moderates in the relation between college stress and psychological well-being. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2006, 38, 422–427. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.Q.; Jing, X.Y. The structure and psychometric valuation of Self-transcendence Meaning of Life Scale in Chinese middle school students and college students: An analyzing perspective from Taoist philosophy and Buddhist philosophy. Psychol. Tech. Appl. 2017, 5, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewitte, L.; Vandenbulcke, M.; Schellekens, T.; Dezutter, J. Sources of well-being for older adults with and without dementia in residential care: Relations to presence of meaning and life satisfaction. Aging Ment. Health 2021, 25, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalom, I. Staring at the sun. Psychologist 2008, 21, 584–585. [Google Scholar]

- Coward, D.D.; Reed, P.G. Self-transcendence: A resource for healing at the end of life. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 1996, 17, 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, P.G. Self-Transcendence: Moving from Spiritual Disequilibrium to Well-Being Across the Cancer Trajectory. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2021, 37, 151212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.J.; Dou, K.; Wang, Y.J.; Nie, Y.G. Why Awe Promotes Prosocial Behaviors? The Mediating Effects of Future Time Perspective and Self-Transcendence Meaning of Life. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, D.F.; Ng, N.; Chen, T.; Hung, T.; Miao, I.Y.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, Y. Let Nature Take Its Course: Cultural Adaptation and Pilot Test of Taoist Cognitive Therapy for Chinese American Immigrants With Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 547852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.J. Self-transcendence in stem cell transplantation recipients: A phenomenologic inquiry. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2012, 39, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. College Stress and Psychological Well-Being: Vision in Life as a Coping Resource. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China, 2022, unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, A.L. Causes of psychological disorders and strategies of self-transcendence. Course Educ. Res. 2013, 8, 84–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugan, G.; Kuven, B.M.; Eide, W.M.; Taasen, S.E.; Rinnan, E.; Xi Wu, V.; Drageset, J.; André, B. Nurse-patient interaction and self-transcendence: Assets for a meaningful life in nursing home residents? BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwamoto, R.; Yamawaki, N.; Sato, T. Increased self-transcendence in patients with intractable diseases. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2011, 65, 638–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Yang, F. Self-transcendence or self-enhancement: People’s perceptions of meaning and happiness in relation to the self. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2022. advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.R.; Liu, M.; Lv, Q. Validity and reliability of the Chinese version of the Self-Transcendence Scale (adolescent version). Chin. Ment. Health J. 2018, 32, 689–694. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, J.C.; Burton, M.; Griffin, M.T.Q.; Fitzpatrick, J.J. Self-transcendence, spiritual well-being, and spiritual practices of women with breast cancer. J. Holist. Nurs. 2010, 28, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano, G.P.; Calong, K.A.C. Spiritual well-being, self-transcendence, and spiritual practices among Filipino women with breast cancer. Palliat. Support. Care 2021, 19, 723–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jadidmilani, M.; Ashktorab, T.; AbedSaeedi, Z.; AlaviMajd, H. The impact of self-transcendence on physical health status promotion in multiple sclerosis patients attending peer support groups. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2015, 21, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.M.; Liu, H.; Qi, X. Functional mechanism of flexible work arrangements in the context of work/family conflicts: Based on work/family boundary theory. J. Bus. Econ. 2019, 12, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlaďo, P.; Dosedlová, J.; Harvánková, K.; Novotný, P.; Gottfried, J.; Rečka, K.; Petrovová, M.; Pokorný, B.; Štorová, I. Work Ability among Upper-Secondary School Teachers: Examining the Role of Burnout, Sense of Coherence, and Work-Related and Lifestyle Factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Hu, Y.; Li, Z.X. Large-scale online teaching: Practical perception and urban-rural differences -- based on a questionnaire survey of 3107 primary and middle school teachers. Sci. Explor. Educ. 2022, 40, 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, L.; Chen, J.L.; Deng, C.Z.; Liu, L. Workout of Work—Pressure Questionnaires of Teachers in primary & middle Schools. Theory Pract. Educ. 2005, 25, 37–39. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, J.; Tan, Y.Y. Factors Analysis and countermeasures of primary and secondary school teachers’ pressure. Educ. Res. Mon. 2003, 12, 23–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netemeyer, R.G.; Boles, J.S.; Mcmurrian, R. Development and validation of Work-Family Conflict and Family-Work Conflict scales. J. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 400–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. J. Educ. Meas. 2013, 51, 335–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Q.; Zhang, D.J. A Model Study on the Relationship between Mental Quality and Mental Health of Adolescents; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- González-Morales, M.G.; Rodríguez, I.; Peiró, J. A longitudinal study of coping and gender in a female-dominated occupation: Predicting teachers’ burnout. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2010, 15, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Liang, L.; Li, H. Emotional Labor and Professional Identity in Chinese Early Childhood Teachers: The Gendered Moderation Models. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Arroyo, J.A.; Osca Segovia, A.; Peiró, J. Meta-analytical review of teacher burnout across 36 societies: The role of national learning assessments and gender egalitarianism. Psychol. Health 2019, 34, 733–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugan, G.; Hanssen, B.; Moksnes, U.K. Self-transcendence, nurse-patient interaction and the outcome of multidimensional well-being in cognitively intact nursing home patients. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2013, 27, 882–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.J. Discussion on Liang Qichao’s philosophy of history. J. Party Sch. CPC Ningbo Munic. Comm. 2022, 44, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.C.; Liu, Z.W. Secrets to Su Shi’s Happiness under Any Circumstances: Transcending and a Positive Perspective. Int. J. Appl. Linguist. Engl. Lit. 2019, 8, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrelli, I.; Benevene, P.; Fiorilli, C.; D’Amelio, F.; Pozzi, G. Working conditions and mental health in teachers: A preliminary study. Occup. Med. 2014, 64, 530–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, J.; Burton, N.W.; McCuaig-Holcroft, L.; Kellmann, M. “I never thought it would be that bad”—Increasing teachers’ awareness of psychological well-being through recovery-stress monitoring and individualised feedback. Work 2021, 69, 1217–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. The Dissolution and Response of Teachers’ Knowledge Authority in the Era of Big Data. Master Dissertation, Central China Normal University, Wuhan, China, 2020. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbname=CMFD202101&filename=1020128244.nh (accessed on 1 May 2020).

- Herman, K.C.; Prewett, S.L.; Eddy, C.L.; Savala, A.; Reinke, W.M. Profiles of middle school teacher stress and coping: Concurrent and prospective correlates. J. Sch. Psychol. 2020, 78, 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, M.; Chang, C.H.; Shi, J.; Zhou, L.; Shao, R. Work-family conflict, emotional exhaustion, and displaced aggression toward others: The moderating roles of workplace interpersonal conflict and perceived managerial family support. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 793–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H.L.; Tu, C.T.; Chan, H.S. Self-transcendence, caring and their associations with well-being. J. Adv. Nurs. 2019, 75, 1473–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.H. Social Psychology; Higher Education Press: Beijing, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D.S.; Zhang, Y.L.; Xiao, S.Y.; Zhou, L.; Zhu, J.F. Introduction to Chinese Taoist Cognitive therapy. Chin. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2002, 2, 152–154. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Y.; Wang, L.; Chen, J.; Zhao, J.; Guo, W. Chinese Taoist Cognitive Therapy for Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety in Adults in China: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J. Buddhism-as-a-meaning-system for coping with late-life stress: A conceptual framework. Aging Ment. Health 2018, 22, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| M ± SD | Age | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Work stress | 27.01 ± 10.21 | 0.152 *** | 1 | |||||

| 2. Family-to-work conflict | 12.14 ± 6.86 | −0.082 | 0.306 *** | 1 | ||||

| 3. well-being | 18.25 ± 3.55 | −0.017 | −0.505 *** | −0.262 *** | 1 | |||

| 4. SMLS | 24.74 ± 4.15 | 0.016 | −0.179 *** | −0.203 *** | 0.238 *** | 1 | ||

| 5. Factor-GMF | 8.81 ± 1.79 | 0.000 | −0.184 *** | −0.167 *** | 0.226 *** | 0.890 *** | 1 | |

| 6. Factor-DSF | 15.94 ± 2.68 | 0.025 | −0.155 *** | −0.202 *** | 0.218 *** | 0.953 *** | 0.710 *** | 1 |

| Sex | Type of School (Primary/Secondary) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (Men/Women) | t | p | M (Primary/Secondary) | t | p | |

| 1. Work stress | 25.52/28.49 | 3.50 ** | <0.01 | 26.60/29.34 | −2.44 * | <0.05 |

| 2. Family-to-work conflict | 11.42/12.85 | 2.49 * | <0.05 | 11.89/13/38 | −1.97 * | <0.05 |

| 3. well-being | 18.50/18.00 | −1.67 | >0.05 | 18.42/17.29 | 2.88 ** | <0.01 |

| 4. SMLS | 25.16/24.33 | −2.39 * | <0.05 | 24.87/24.22 | 1.41 | >0.05 |

| 5. Factor-GMF | 8.95/8.67 | −1.85 | >0.05 | 8.90/8.41 | 2.47 * | <0.05 |

| 6. Factor-DSF | 16.22/15.66 | −2.46 * | <0.05 | 15.97/15.81 | 0.53 | >0.05 |

| Outcome Variable | Regulated Variable | Predictive Variable | β | BootLLCI | BootULCI | t | R2 | F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Well-being | self-transcendent meaning of life | Work stress | −0.15 | −0.176 | −0.118 | −10.52 *** | 0.29 | 32.44 *** |

| Family-to-work conflict | −0.04 | −0.087 | −0.002 | −2.21 * | ||||

| Work stress * SMLS | −0.01 | −0.011 | −0.001 | −2.24 * | ||||

| Factor-DSF | Work stress | −0.15 | −0.182 | −0.127 | −10.42 *** | 0.29 | 31.73 *** | |

| Family-to-work conflict | −0.05 | −0.089 | −0.004 | −2.40 * | ||||

| Work stress * Factor-DSF | −0.01 | −0.015 | >−0.001 | −2.07 * | ||||

| Work stress | −0.15 | −0.178 | −0.121 | −10.81 *** | 0.29 | 32.11 *** | ||

| Factor-GMF | Family-to-work conflict | −0.04 | −0.087 | −0.002 | −2.43 * | |||

| Work stress * Factor-GMF | −0.01 | −0.016 | −0.001 | −2.21 * |

| Moderating Variable | Level of Factor | Path | Effect Size | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| self-transcendence meaning of life | M − SD | X→Y | −0.12 | −0.163 | −0.086 |

| M | X→Y | −0.15 | −0.175 | −0.120 | |

| M + SD | X→Y | −0.17 | −0.201 | −0.141 | |

| Factor-DSF | M − SD | X→Y | −0.13 | −0.165 | −0.086 |

| M | X→Y | −0.15 | −0.176 | −0.120 | |

| M + SD | X→Y | −0.17 | −0.200 | −0.140 | |

| M − SD | X→Y | −0.13 | −0.165 | −0.089 | |

| Factor-GMF | M | X→Y | −0.15 | −0.178 | −0.123 |

| M + SD | X→Y | −0.17 | −0.205 | −0.144 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liao, J.; Wang, X.-Q.; Wang, X. The Effect of Work Stress on the Well-Being of Primary and Secondary School Teachers in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1154. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021154

Liao J, Wang X-Q, Wang X. The Effect of Work Stress on the Well-Being of Primary and Secondary School Teachers in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(2):1154. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021154

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiao, Jingyi, Xin-Qiang Wang, and Xiang Wang. 2023. "The Effect of Work Stress on the Well-Being of Primary and Secondary School Teachers in China" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 2: 1154. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021154

APA StyleLiao, J., Wang, X.-Q., & Wang, X. (2023). The Effect of Work Stress on the Well-Being of Primary and Secondary School Teachers in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 1154. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021154