Associations between Stressful Life Events and Increased Physical and Psychological Health Risks in Adolescents: A Longitudinal Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants/Study Sample

2.2. Life Events Questionnaire

2.3. KIDSCREEN-27

2.4. Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)

2.5. Body Mass Index (BMI)

2.6. Socioeconomic Status (SES)

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

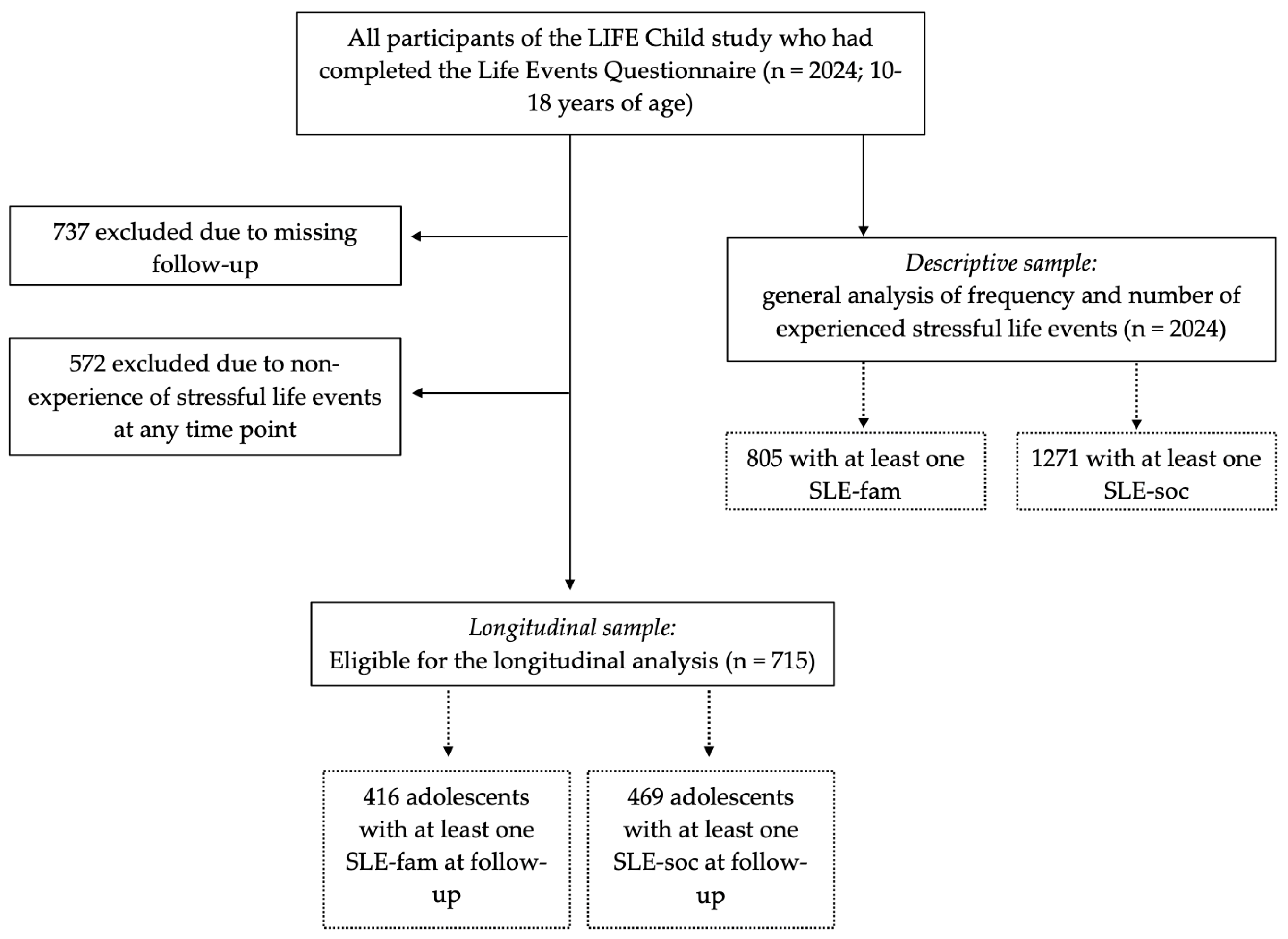

3.1. Study Sample

3.2. Descriptive Analysis

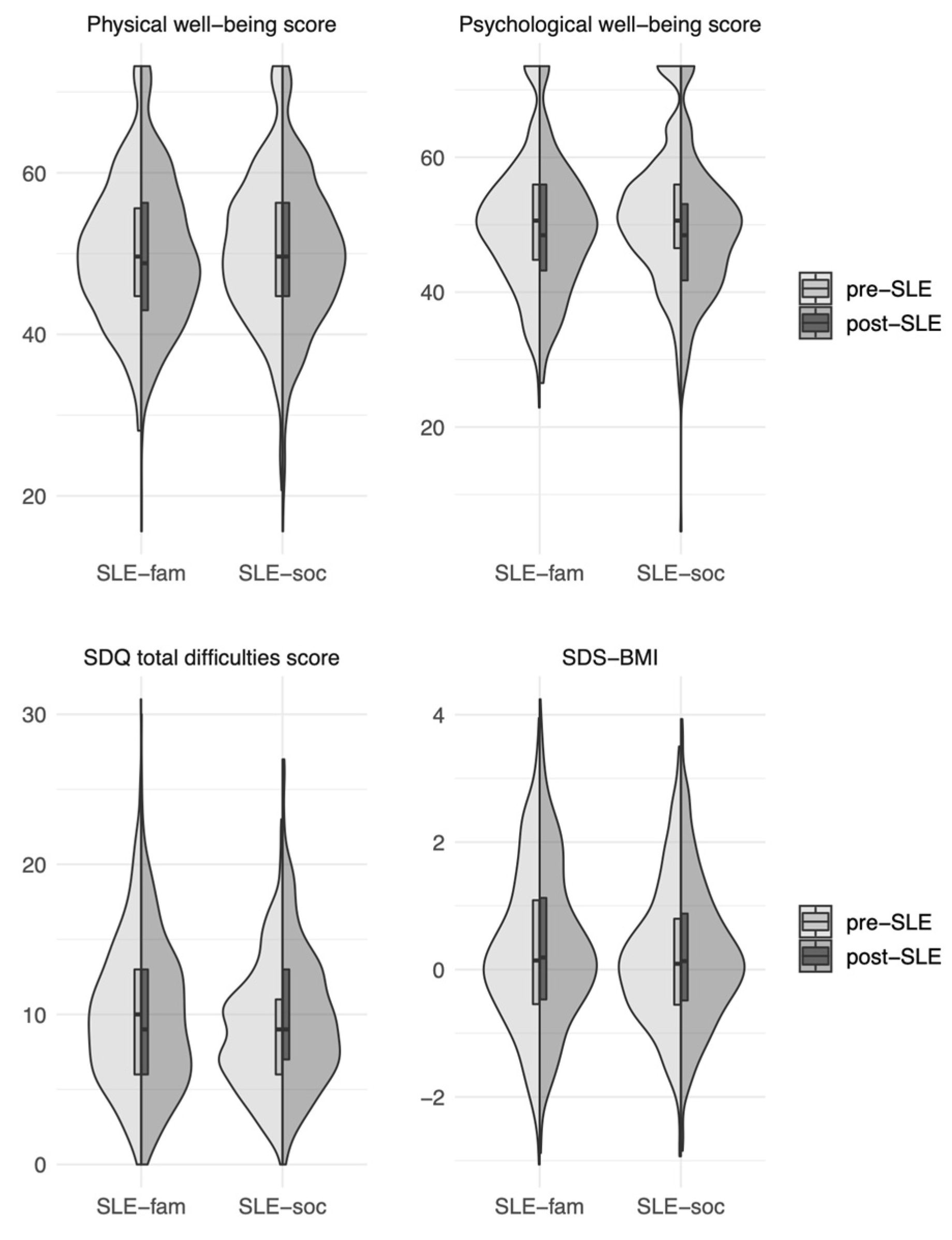

3.3. Longitudinal Analysis: Differences in Health Parameters before and after Experiencing an SLE (Two Sample T-Tests)

3.4. Moderator Analysis: Associations between SES, Age and Sex, and Differences in Health Parameters (Linear Regression Analyses)

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

4.2. Associations between SLEs and Psychological Health Risks

4.3. Associations between SLEs and Physical Health Risks

4.4. SLE in Different Life Domains

4.5. Moderator Analyses

4.6. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cohen, S.; Janicki-Deverts, D.; Miller, G.E. Psychological Stress and Disease. JAMA 2007, 298, 1685–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavich, G.M. Life Stress and Health: A Review of Conceptual Issues and Recent Findings. Teach. Psychol. 2016, 43, 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupien, S.J.; McEwen, B.S.; Gunnar, M.R.; Heim, C. Effects of stress throughout the lifespan on the brain, behaviour and cognition. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2009, 10, 434–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glaser, R.; Kiecolt-Glaser, J.K. Stress-induced immune dysfunction: Implications for health. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005, 5, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, T.H.; Rahe, R.H. The social readjustment rating scale. J. Psychosom. Res. 1967, 11, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S.; Murphy, M.L.; Prather, A.A. Ten Surprising Facts About Stressful Life Events and Disease Risk. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2019, 70, 577–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, E.J.; Erkanli, A.; Fairbank, J.A.; Angold, A. The prevalence of potentially traumatic events in childhood and adolescence. J. Trauma. Stress Off. Publ. Int. Soc. Trauma. Stress Stud. 2002, 15, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, A.; Sachser, C.; Plener, P.L.; Brähler, E.; Fegert, J.M. The Prevalence and Consequences of Adverse Childhood Experiences in the German Population. Dtsch. Aerzteblatt Online 2019, 116, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felitti, V.J.; Anda, R.F.; Nordenberg, D.; Williamson, D.F.; Spitz, A.M.; Edwards, V.; Koss, M.P.; Marks, J.S. Relationship of Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction to Many of the Leading Causes of Death in Adults. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1998, 14, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, K.; Bellis, M.A.; Hardcastle, K.A.; Sethi, D.; Butchart, A.; Mikton, C.; Jones, L.; Dunne, M.P. The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health 2017, 2, e356–e366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, R.; Feely, A.; Layte, R.; Williams, J.; McGavock, J. Adverse childhood experiences are associated with an increased risk of obesity in early adolescence: A population-based prospective cohort study. Pediatr. Res. 2019, 86, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C. The effects of stressful life events on depression. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1997, 48, 191–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spear, L.P. The adolescent brain and age-related behavioral manifestations. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2000, 24, 417–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paus, T.; Keshavan, M.; Giedd, J.N. Why do many psychiatric disorders emerge during adolescence? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2008, 9, 947–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baddam, S.K.; Olvera, R.L.; Canapari, C.A.; Crowley, M.J.; Williamson, D.E. Childhood Trauma and Stressful Life Events Are Independently Associated with Sleep Disturbances in Adolescents. Behav. Sci. 2019, 9, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, J.P.; Su, S.S. Stressful Life Events and Adolescent Substance Use and Depression: Conditional and Gender Differentiated Effects. Subst. Use Misuse 1998, 33, 2219–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, K.A.; Hatzenbuehler, M.L. Mechanisms Linking Stressful Life Events and Mental Health Problems in a Prospective, Community-Based Sample of Adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2009, 44, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yıldız, M. Stressful life events and adolescent suicidality: An investigation of the mediating mechanisms. J. Adolesc. 2020, 82, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Li, L.; Xu, Y.; Pan, G.; Tao, F.; Ren, L. Associations between screen time, negative life events, and emotional and behavioral problems among Chinese children and adolescents. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 264, 506–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coker, T.R.; Elliott, M.N.; Wallander, J.L.; Cuccaro, P.; Grunbaum, J.A.; Corona, R.; Saunders, A.E.; Schuster, M.A. Association of Family Stressful Life-Change Events and Health-Related Quality of Life in Fifth-Grade Children. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2011, 165, 354–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Gutierrez, G.; Wallander, J.L.; Yang, Y.; Depaoli, S.; Elliott, M.N.; Coker, T.R.; Schuster, M.A. Racial/Ethnic Differences in the Relationship Between Stressful Life Events and Quality of Life in Adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 68, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villalonga-Olives, E.; Rojas-Farreras, S.; Vilagut, G.; Palacio-Vieira, J.A.; Valderas, J.M.; Herdman, M.; Ferrer, M.; Rajmil, L.; Alonso, J. Impact of recent life events on the health related quality of life of adolescents and youths: The role of gender and life events typologies in a follow-up study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2010, 8, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- March-Llanes, J.; Marqués-Feixa, L.; Mezquita, L.; Fañanás, L.; Moya, J. Stressful life events during adolescence and risk for externalizing and internalizing psychopathology: A meta-analysis. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2017, 26, 1409–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compas, B.E. Stress and life events during childhood and adolescence. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 1987, 7, 275–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booker, C.L.; Unger, J.B.; Azen, S.P.; Baezconde-Garbanati, L.; Lickel, B.; Johnson, C.A. A Longitudinal Analysis of Stressful Life Events, Smoking Behaviors, and Gender Differences in a Multicultural Sample of Adolescents. Subst. Use Misuse 2008, 43, 1521–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conklin, A.I.; Guo, S.X.; Tam, A.C.; Richardson, C.G. Gender, stressful life events and interactions with sleep: A systematic review of determinants of adiposity in young people. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e019982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, S.K.; Pangelinan, M.; Björnholm, L.; Klasnja, A.; Leemans, A.; Drakesmith, M.; Evans, C.; Barker, E.; Paus, T. Associations between prenatal, childhood, and adolescent stress and variations in white-matter properties in young men. NeuroImage 2018, 182, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickrama, K.A.; Lee, T.K.; O'Neal, C.W. Stressful Life Experiences in Adolescence and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors in Young Adulthood. J. Adolesc. Health 2015, 56, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, A.; Wang, B.; Kunze, B.; Otto, C.; Schlack, R.; Hölling, H.; Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Klasen, F.; Rogge, J.; Isensee, C.; et al. Normative Data of the Self-Report Version of the German Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire in an Epidemiological Setting. Z. Für Kinderund Jugendpsychiatrie Und Psychother. 2018, 46, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiss, F.; Meyrose, A.-K.; Otto, C.; Lampert, T.; Klasen, F.; Ravens-Sieberer, U. Socioeconomic status, stressful life situations and mental health problems in children and adolescents: Results of the German BELLA cohort-study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Auquier, P.; Erhart, M.; Gosch, A.; Rajmil, L.; Bruil, J.; Power, M.; Duer, W.; Cloetta, B.; Csémy, L.; et al. The KIDSCREEN-27 quality of life measure for children and adolescents: Psychometric results from a cross-cultural survey in 13 European countries. Qual. Life Res. 2007, 16, 1347–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quante, M.; Hesse, M.; Döhnert, M.; Fuchs, M.; Hirsch, C.; Sergeyev, E.; Casprzig, N.; Geserick, M.; Naumann, S.; Koch, C.; et al. The Life Child Study: A Life Course Approach to Disease and Health. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poulain, T.; the LIFE Child study team; Baber, R.; Vogel, M.; Pietzner, D.; Kirsten, T.; Jurkutat, A.; Hiemisch, A.; Hilbert, A.; Kratzsch, J.; et al. The Life Child Study: A Population-Based Perinatal and Pediatric Cohort in Germany. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 32, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bundesagentur Für Arbeit Statistik. Übersicht Leipzig, Stadt. 2022. Available online: https://statistik.arbeitsagentur.de/Auswahl/raeumlicher-Geltungsbereich/PolitischeGebietsstruktur/Bundeslaender/Sachsen.html?nn=25856 (accessed on 22 December 2022).

- Stadt Leipzig Amt Für Statistik Und Wahlen. Kommunale Bürgerumfrage. 2022. Ergebnisbericht. Available online: https://www.leipzig.de/buergerservice-und-verwaltung/buergerbeteiligung-und-einflussnahme/buergerumfrage/ (accessed on 22 December 2022).

- Ravens-Sieberer, U. The Kidscreen Questionnaires: Quality of Life Questionnaires for Children and Adolescents; Pabst Science Publishers: Lengerich, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Herdman, M.; Devine, J.; Otto, C.; Bullinger, M.; Rose, M.; Klasen, F. The European KIDSCREEN approach to measure quality of life and well-being in children: Development, current application, and future advances. Qual. Life Res. 2013, 23, 791–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, R. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A Research Note. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 1997, 38, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, R.; Meltzer, H.; Bailey, V. The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: A pilot study on the validity of the self-report version. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1998, 7, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kromeyer-Hauschild, K.; Wabitsch, M.; Kunze, D.; Geller, F.; Geiß, H.C.; Hesse, V.; Von Hippel, A.; Jaeger, U.; Johnsen, D.; Korte, W.; et al. Perzentile für den Body-mass-Index für das Kindes-und Jugendalter unter Heranziehung verschiedener deutscher Stichproben. Mon. Kinderheilkd 2001, 149, 807–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, J.; Stolzenberg, H. Adjustierung Des Sozialen-Schicht-Index Für Die Anwendung Im Kinder—Und Jugendgesundheitssurvey (Kiggs) 2003/2006; Hochschule Wismar, Fakultät für Wirtschaftswissenschaften: Wismar, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lampert, T.; KiGGS Study Group; Muters, S.; Stolzenberg, H.; Kroll, L.E. Messung des sozioökonomischen Status in der KiGGS-Studie. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundh. Gesundh. 2014, 57, 762–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. 2018. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 11 February 2021).

- Pervanidou, P.; Chrousos, G.P. Stress and obesity/metabolic syndrome in childhood and adolescence. Int. J. Pediatr. Obes. 2011, 6, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosmond, R. Role of stress in the pathogenesis of the metabolic syndrome. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2005, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helgeson, V.S. Gender, stress, and coping. In The Oxford Handbook of Stress, Health, and Coping; Folkman, S., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 63–85. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, R.H.; Corwyn, R.F. Socioeconomic Status and Child Development. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2002, 53, 371–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Number of Participants, Who Had Experienced This SLE (%) | Number of Participants, Who Had Not Experienced This SLE (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Family problems (SLE-fam) | 805 (39.8) | 1205 (59.5) | |

| Divorce of parents | 170 (8.4) | 1829 (90.4) | |

| Death of a close family member | 577 (28.5) | 1416 (70.0) | |

| Unemployment within the family | 286 (14.1) | 1712 (84.6) | |

| Problems in the social environment (SLE-soc) | 1271 (62.8) | 712 (35.2) | |

| Victim of bullying or violence | 864 (42.7) | 1156 (57.1) | |

| Problems among friends | 616 (30.4) | 1390 (68.7) | |

| Moving to a different place of Residence | 249 (12.3) | 1751 (86.5) | |

| Separation from partner | 554 (27.4) | 1444 (71.3) |

| KIDSCREEN Physical Well-Being Score | KIDSCREEN Psychological Well-Being Score | SDQ Total Difficulties Score | BMI-SDS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family problems (SLE-fam) | ||||

| Number of included participants | 414 | 412 | 399 | 416 |

| Pre-SLE-fam | M = 50.06 sd = 8.67 | M = 50.50 sd = 9.86 | M = 10.02 sd = 4.90 | M = 0.28 sd = 1.24 |

| Post-SLE-fam | M = 50.23 sd = 9.45 | M = 49.43 sd = 9.81 | M = 9.66 sd = 4.96 | M = 0.34 sd = 1.24 |

| Difference in means | 0.17 | −1.07 | −0.36 | 0.06 |

| p | 0.705 | 0.02 | 0.07 | <0.01 |

| Problems in the social environment (SLE-soc) | ||||

| Number of included participants | 460 | 460 | 438 | 469 |

| Pre-SLE-soc | M = 50.95 sd = 9.14 | M= 51.89 sd = 10.16 | M = 8.93 sd = 4.08 | M = 0.19 sd = 1.11 |

| Post-SLE-soc | M = 49.78 sd = 9.31 | M = 49.14 sd = 10.13 | M = 9.92 sd = 4.77 | M = 0.23 sd = 1.13 |

| Difference in means | −1.17 | −2.74 | 0.98 | 0.04 |

| p | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.036 |

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variable | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Female Sex | SES | ||

| Family problems | ||||

| Physical well-being (KIDSCREEN) | b | 0.16 | −2.53 | 0.28 |

| 95% CI | −0.29; 0.61 | −4.13; −0.92 | 0.04; 0.51 | |

| p | 0.49 | 0.002 | 0.02 | |

| Psychological well-being (KIDSCREEN) | b | 0.09 | −2.74 | 0.22 |

| 95% CI | −0.34; 0.52 | −4.31; −1.16 | −0.01; 0.44 | |

| p | 0.69 | <0.001 | 0.06 | |

| Total difficulties score (SDQ) | b | 0.15 | 0.55 | −0.09 |

| 95% CI | −0.08; 0.38 | −0.25; 1.35 | −0.2; 0.03 | |

| p | 0.21 | 0.18 | 0.15 | |

| BMI-SDS | b | −0.0005 | 0.03 | 0.003 |

| 95% CI | −0.02; 0.02 | −0.04; 0.10 | −0.01; 0.01 | |

| p | 0.96 | 0.34 | 0.52 | |

| Problems in the social environment | ||||

| Physical well-being (KIDSCREEN) | b | 0.02 | −3.94 | 0.08 |

| 95% CI | −0.36; 0.40 | −5.38; −2.49 | −0.13; 0.28 | |

| p | 0.90 | <0.0001 | 0.47 | |

| Psychological well-being (KIDSCREEN) | b | −0.08 | −4.54 | −0.07 |

| 95% CI | −0.52; 0.35 | −6.27; −2.80 | −0.31; 0.17 | |

| p | 0.71 | <0.0001 | 0.58 | |

| Total difficulties score (SDQ) | b | −0.01 | 0.58 | −0.09 |

| 95% CI | −0.24; 0.21 | −0.24; 1.41 | −0.21; 0.03 | |

| p | 0.90 | 0.17 | 0.13 | |

| BMI-SDS | b | 0.002 | 0.05 | −0.01 |

| 95% CI | −0.02; 0.02 | −0.02; 0.12 | −0.02; 0.003 | |

| p | 0.83 | 0.16 | 0.16 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roth, A.; Meigen, C.; Hiemisch, A.; Kiess, W.; Poulain, T. Associations between Stressful Life Events and Increased Physical and Psychological Health Risks in Adolescents: A Longitudinal Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1050. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021050

Roth A, Meigen C, Hiemisch A, Kiess W, Poulain T. Associations between Stressful Life Events and Increased Physical and Psychological Health Risks in Adolescents: A Longitudinal Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(2):1050. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021050

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoth, Anna, Christof Meigen, Andreas Hiemisch, Wieland Kiess, and Tanja Poulain. 2023. "Associations between Stressful Life Events and Increased Physical and Psychological Health Risks in Adolescents: A Longitudinal Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 2: 1050. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021050

APA StyleRoth, A., Meigen, C., Hiemisch, A., Kiess, W., & Poulain, T. (2023). Associations between Stressful Life Events and Increased Physical and Psychological Health Risks in Adolescents: A Longitudinal Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 1050. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021050