Elucidating and Expanding the Restorative Theory Framework to Comprehend Influential Factors Supporting Ageing-in-Place: A Scoping Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

The General Theory Framework of Psychological Restoration

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Identification

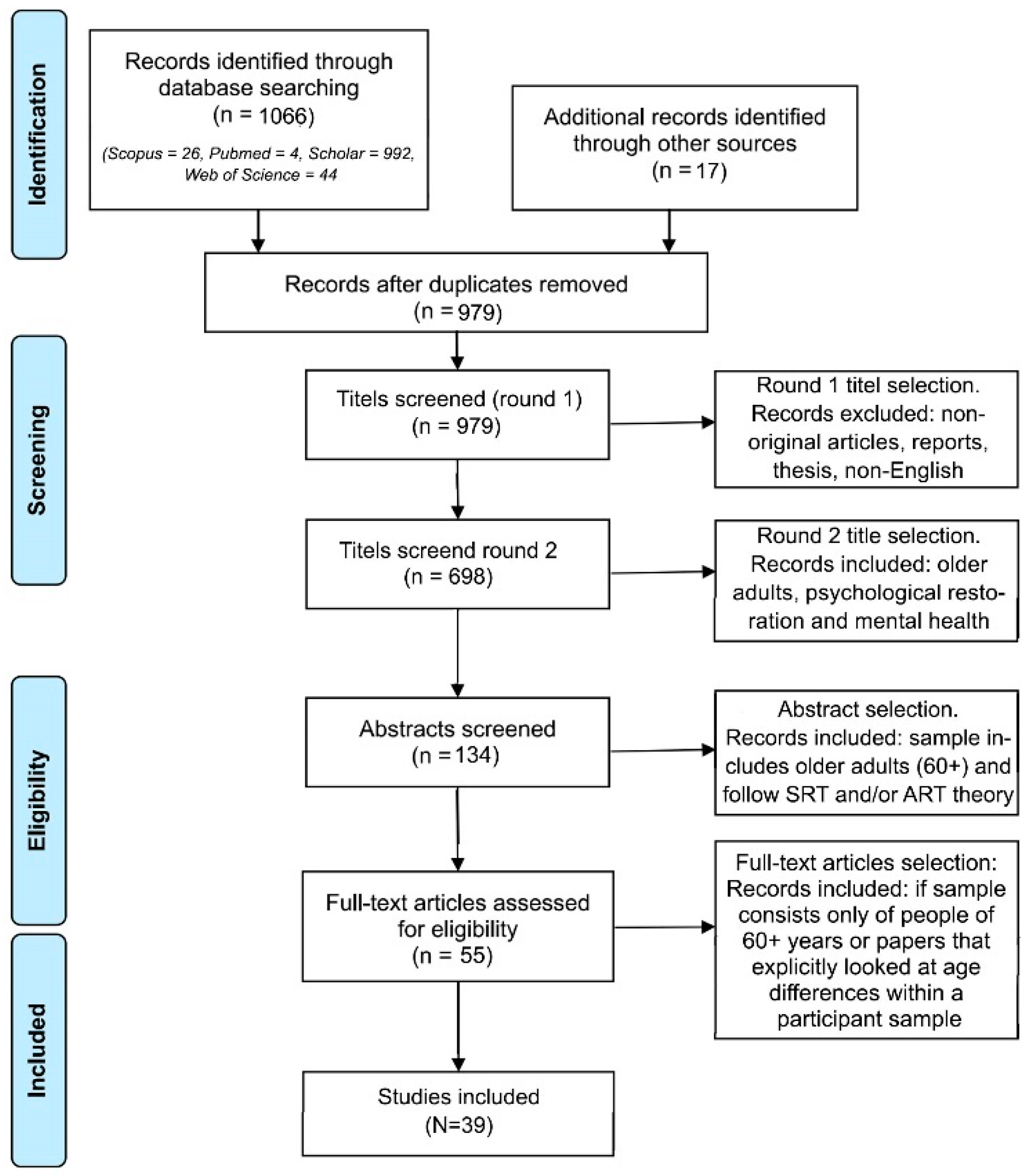

2.3. Screening and Study Selection

2.4. Data Charting

2.5. Collation, Summarising and Analysis

3. Results

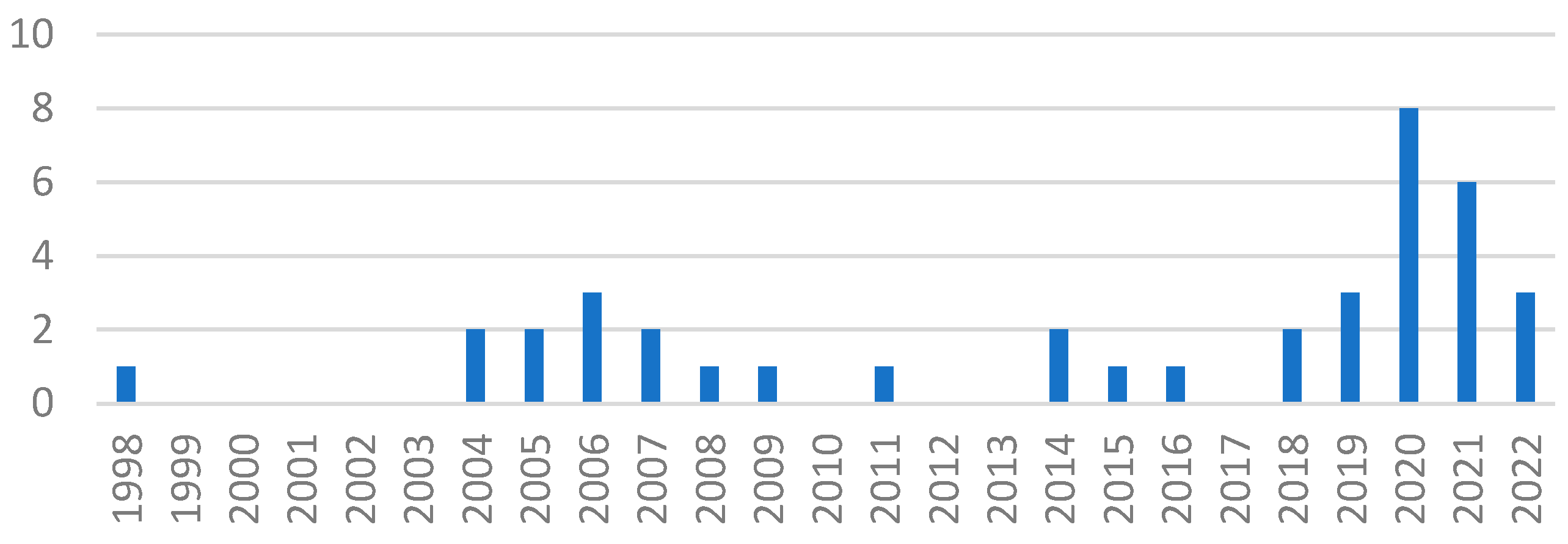

3.1. Descriptive Results

3.2. The General Restorative Theory Framework

3.2.1. Features That Permit Restoration for Older Populations

| Theory | Features of P-E Transactions That Permit Restoration for the Older Population | Features of P-E Transactions That Promote Restoration for the Older Population | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stress Reduction Theory (SRT) | Absence of uncontrollable threat | An essential feature of older adults’ restoration process. If older adults feel unsafe in an environment, restoration cannot occur [51,54,55,58,59,60,61,63,64,65,66]. | Perception of natural contents | Scenes with water support feelings of calmness and relaxation due to sensory stimulation, also for the older population [22,28,55,59,61,63,64,68]. |

Visual stimulus attributes | Deflected vistas can enhance curiosity and motivate older adults to go outdoors and explore their everyday environments. There needs to be a right balance of prospect and refuge. Ability to see the environment without feeling exposed [26,50,59,60,61,62,63,65,69]. | |||

Moderate levels of complexity | Not named in the reviewed literature in the context of the older population. | |||

Gross structure | Not named in the reviewed literature in the context of the older population. | |||

| Attention Restoration Theory (ART) | Being away | Doubt arises in which way the component being-away is essential for older adults’ restoration process. Escape from every day routines is challenged by the need for social interaction [17,22,26,27,54,55,56,57,58,59,61,67,70,71]. | Fascination | An important feature of older adults’ restoration process. Encourages older adults to explore their surroundings. Authors propose that fascination for older adults is not stimulated by ‘newness’ but by experiencing the familiar in a new way [17,20,22,26,52,53,54,57,58,59,61,64,65,69,70,72,73]. |

Compatibility | Due to changing capabilities, this feature becomes essential for the restoration process of the older population. Lack of compatibility between the person and the environment dramatically decreases the restorative potential for older adults. Aspects of accessibility play an important role in this feature [17,20,22,26,50,52,54,55,57,58,59,61,64,65,69,70,74]. | Extent | Linked to the presence of (childhood) memories and sensory stimulation. Not named as a condition that will change for the older population [17,20,22,26,57,58,59,61,64,65]. | |

Compatibility | An essential feature for the restoration process of older adults. Although their capabilities change, the environment should enable their life activities [22,54,55,58,59,61,64,65,69,70]. | |||

| Outside conventional theories | Being with | Being-with others is suggested as an essential feature of the restoration process of older adults; however, individual needs need to be taken into account [17,20,22,50,51,52,54,55,56,59,60,61,63,64,65,67,71,75,76,77]. | Familiarity | Familiarity can be an additional feature of older adults’ restoration process. Familiar environments can enhance feelings of safety and comfort, promoting the restoration process. A balance between new and familiar elements is important to prevent over or under-stimulation [20,52,55,57,62,64,65,66,74]. |

3.2.2. Features That Promote Restoration for Older Populations

3.3. Additional Features for the General Restorative Theory Framework

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Author | Country | Research Type and Theory | Method | Measures (Psychological Restoration Measures and Other Measures) | Participant Number and Age | Other Sample Characteristics | Type of Environment | Factors That Permit Restoration for Older Adults | Factors That Promote Restoration for Older Adults | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berto (2007) [74] | Italy | Empirical study Quantitative ART | Lab study Photo evaluation Questionnaire | Italian PRS Preference Familiarity | N = 50 Aged between 62–93 years M = 80 years | All living in a place for older adults. Half live in a natural setting, and half in an urban setting. | Nature and urban environments (Housing, industrial zone, city streets, hills, lakes) | Compatibility | Deflected vista Familiarity | Experimental study comparing different age groups. |

| Boffi, Pola, Fumagalli, et al. (2021) [70] | Italy | Empirical study Qualitative ART | Lab study Focus groups | Study 1 Descriptions of restorative environments | N = 23 Aged between 65–84 years | More female | Nature environment (Urban community shared garden) | Compatibility Being-away | Fascination | Nature experiences enhance active ageing. Interdisciplinary approach to codesign community gardens |

| Study 2 Analyses descriptions of restorative experiences | N = 25 Aged between 65–84 years | More female | ||||||||

| Boffi, Grazia Pola, Fermani, et al. (2022) [34] | Italy | Empirical study Quantitative ART | In situ study Questionnaire | Italian PRS Self-assessment Manikin Activity list | N = 81 Aged 60+ (Compared within larger group N = 321) | Nature environment (Urban community shared garden) | Compatibility | Post occupancy evaluation of virtual restorative garden with different age groups | ||

| Cassarino, Tuohy, Setti (2019) [62] | Ireland | Empirical study Quantitative ART | Lab study Photo evaluation Attention tasks Questionnaire | Short PRS SART | N = 75 Aged between 60–95 years | More males. Healthy individuals. No cognitive deficits. Half live in a natural setting, and half in an urban setting. A total of 82% reported easy access to green space in their neighbourhood. | Nature and urban environments (Various images are taken from the internet with no people and no water.) | Familiarity | Experimental study measuring attention restoration of older adults while viewing different scenes. | |

| Chan, Qiu, Esposito, et al. (2021) [86] | Singapore | Empirical study Quantitative SRT | Lab study Virtual reality Physiological measures Questionnaire | Cardiovascular activity ECG Self-reported stress Positive affect Nature connectedness | N = 26 M = 72.7 years | Nature and urban environment (Virtual reality forest and streets) | Deflected vista | Viewing nature scenes in VR can reduce stress in young and older adults. | ||

| Chen, Yuan (2020) [75] | China | Empirical study Quantitative SRT | Lab study Photo evaluation Questionnaire | Self-reported stress Mental health (SF-36) Blue space scale Air quality index Physical activity Social contact SES | N = 966 M = 69 years | Male/female was equally divided. Low education levels. Most were married. Most of them retired. Half were local residents. | Nature environment (Blue spaces in the city) | Social context | Study if blue space in the neighbourhood affects older adults’ mental health, a case study. | |

| Elsadek, Shao, Liu (2021) [87] | China | Empirical study Quantitative SRT | Lab study Photo evaluation Physiological measures Brain activity (EEG) | Heart rate variability Skin conductance Alpha waves Mood scales | N = 29 M = 82.9 years | Nature and urban environment (Bamboo forest and urban scenes) | Experimental study if nature images impact older adults’ brain activity and autonomic nervous system. | |||

| Finlay, Franke, McKay, et al. (2015) [55] | Canada | Empirical study Qualitative ART | In situ study Walk and Talk interviews | Analyses descriptions of restorative experiences using 4 ART components Interpretation and interaction with the local neighbourhood context Emotional responses | N = 27 Aged between 65–86 years | Leaving their home at least once a week. Able to walk 10 m (with mobility aid). No sig. memory problems. Eight different self-identified racial and ethnic groups: Caucasian, aboriginal, Chinese, Southeast Asian, Japanese, Filipino, Dutch, and German. | Nature and urban environment (Participants could indicate restorative spaces in their neighbourhood) | Safety Being away Compatibility Social context | Ground Cover Water Familiarity Compatibility | Qualitative study—Talking with older adults about how blue and green spaces impact their well-being. |

| Fumagalli, Fermani, Senes, et al. (2020) [22] | Italy | Literature review Codesign Mixed-method ART | Lab study and real life (not in situ) Focus groups | Analyses descriptions of restorative experiences using 4 ART components | N = 23 Aged between 65–84 years | All participants were from the same neighbourhood. | Nature environment (Urban community shared garden) | Being-away Compatibility Social context | Deflected vista Water Extent (coherence) Fascination Compatibility | Co-design together with older adults a restorative garden, a case study. |

| Gamble, Howard, Howard (2014) [88] | United States | Empirical study Quantitative ART | Lab study Photo evaluation Attention tests Questionnaire | ANT test Backward digit span PANAS | N = 30 Aged between 64–79 (Compared with young university students aged between 18–25 (N = 26)) | All-in good health. Mini-Mental State Examination was good. | Nature and urban environment (Nature scenery of Nova Scotia, Ann Arbor, Detroit and Chicago) | Experimental study if viewing nature images improves attention in older adults. | ||

| Hawkins, Thirlaway, Backx, et al. (2011) [67] | United Kingdom | Empirical study Quantitative SRT | In situ study Physiological measures Questionnaire | Systolic and diastolic blood pressure Perceived stress Lung function Body mass BMI Self-rated health Physical activity level Social activity level Perceived social support | N = 94 Aged between 50–88 years | Members of various indoor and outdoor activity groups. All were gardeners at private or allotment gardens. | Nature environment (Community activity group garden) | Being away Social context | Study if allotment gardening can reduce stress for older adults. | |

| Husser, Roberto, Allen (2020) [26] | United States | Empirical study Mixed method ART | Real-life study (not in situ) Interviews | Analyses of descriptions of interview data using the four ART characteristics Physical measures Health and coping Social support network Quality of Life | N = 34 Aged between 71–91 years | All women lived in a small mountainous community. More than half lived there for over 50 years. Half lived alone. 24% lived below the poverty line. | Nature environment (Rural area) | Being away Compatibility Social context | Extent Fascination | Analysing interviews with rural living older woman and what influence nature has on their lives. Using grounded theory techniques. A connection is made between nature and coping with ageing challenges. |

| Jang, Jeong, Kim, et al. (2020) [73] | Korea | Empirical study Quantitative ART | In situ study Questionnaire | Korean PRS PANAS Plant cultivation activity levels Satisfaction Loyalty | N = 65 Aged 60+ (Compared within larger group N = 285) | Male/female was equally divided. Educated. Middle incomes. | Nature environment (Shared healing garden) | Fascination | Experimental study viewing images of healing gardens and testing if different age groups experienced attention restoration. Focus of the study on component fascination. | |

| Jansen (2008) [76] | United States | Empirical study Quantitative ART | Real-life study (not in situ) Questionnaire Activity assessment | RAA Attention function index Geriatric depression scale Self-rated health | N = 54 Aged between 65–87 years | Living independently in the community. Most lived in a single home. Half lived alone. Half is married. | Nature and urban environments (Participants could suggest their own restorative environments) | Social context | Gathering an overview of restorative activities for community-dwelling older adults. Follow-up study. | |

| Jansen (2005) [56] | United States | Empirical study Qualitative ART | Real-life study (not in situ) Interviews | Analyses of descriptions of interview data Identify barriers to restorative activities | N = 30 Aged between 65–92 years. | Community dwelling. Half married. A total of 77% lived alone. Average education 13,2 years. A total of 77% rated good/excellent health. | Nature and urban environments (Participants could suggest their own restorative environments) | Safety Being-away Social context | Gathering an overview of community-dwelling older adults’ barriers to participating in restorative activities. | |

| Jansen, von Sadovszky (2004) [58] | United States | Empirical study Qualitative ART | Real-life study (not in situ) Interviews | Analyses of descriptions of restorative experiences | N = 30 Aged between 65–92 years | Mostly women. Community-dwelling. Half married. A total of 77% lived alone. Average education 13,2 years. A total of 77% rated good/ excellent health. | Nature and urban environments (Participants could suggest their own restorative environments) | Safety Being away Compatibility Social context | Extent Fascination Compatibility | Gathering an overview of restorative activities for community-dwelling older adults. |

| Jarosz (2022) [28] | Poland | Empirical study Qualitative SRT | Lab study Experience Sampling Method (telephone interviews) | Self-reported stress Self-reported Enjoyment | N = 200 Aged 65+ years | Non-institutionalised | Nature and urban environment | Presence of water | The study used a new method—experience sampling method—to collect user experiences. Results show that people in green or blue spaces had more enjoyment and less stress. | |

| Kabisch, Püffel, Masztalerz, et al. (2021) [27] | Germany | Empirical study Quantitative ART and SRT | In situ study Questionnaire Physiological measures | Heart rate variability ECG Blood pressure ROS POMS Green space visitation pattern Familiarity Medication BMI Short health survey Self-perceived health Perception of naturalness | N = 33 Aged between 55–70 years M = 63.5 years | Male/female was equally divided. Non-smokers with a healthy heart. Could walk for 30 min. Are regularly active. | Nature environment (Urban park) | Being away Social context | Field experiment if older adults experience physiological and psychological effects after visiting inner city areas. | |

| Li, Liu, Yang, et al. (2021) [60] | China | Empirical study Quantitative ART and SRT | In situ study Questionnaire Physiological measures | Blood pressure Heart rate PRS ROS PANAS POMS Illumination Temperature Noise Air Quality Index | N = 45 Aged between 40–71 years | Mostly women. In good health. Absence of severe cardiovascular disease and cognitive impairment. No problems walking | Nature and urban environment (Urban parks, city streets, shops, high-rise buildings) | Safety Social context | Experimental study to test if night-time walking can offer restoration to older adults. | |

| Li, Zhai, Xiao, et al. (2019) [69] | China | Empirical study Quantitative SRT | In situ study Questionnaire Movement data | Self-rated stress levels Affect GPS measures Pedometer data | N = 200 Aged 60+ years | Gender was equally divided. No difficulty walking. Mostly in good health. A total of 75% were married. Half fell in the middle-income category. A total of 65% of participants visited the park almost every day. | Nature environment (Urban park) | Compatibility | Fascination Compatibility | A study collecting self-reported psychological benefits among older adults before and after park visits. |

| Liao, Ou, Heng Hsieh, et al. (2020) [57] | United States | Empirical Study Quantitative ART and SRT | Real-life study (not in situ) Questionnaire | (self) rated attention abilities (self) rated stress Mini-Mental State Exam ADL Appetite Mood Social interaction | N = 42 Care professionals filled in the questionnaires with/for 42 senior patients | Nature environment (Shared Garden of Geriatric care centre) | Safety Being away Compatibility | Extent Fascination Familiarity | Study to test the effect of garden visits on older people with dementia. Care professionals filed a questionnaire for the participants after the garden visit (indirect data collection). | |

| Lu, Oh, Ooka, et al. (2022) [63] | Japan | Empirical study Quantitative ART | In situ study Questionnaire | Japanese ROS Climate conditions Spatial conditions (sky view factor, green view factor, colour index, facilities (toilet, water, seats, pavement)) Vitality | N = 202 Aged 60+ years | More males than females. | Nature environment (Urban park) | Safety Social context | Water | Experimental study to show which environmental features of SPUGS affect mental restoration of older adults (e.g., green, colour, sky factor). |

| Marques, McIntosh, Kershaw (2019) [66] | (Not specified) | Literature Review Medical report analyses Mixed-Method ART and SRT | Nature and urban environment | Safety | Ground cover Familiarity | Review on design elements in therapeutic environments that can offer psychological restoration to older adults. | ||||

| Moore (2007) [61] | United States | Descriptive study Qualitative ART and SRT | In situ study Environmental analyses | Spatial analyses of dementia gardens on the four ART characteristics | Nature environment (Shared therapeutic dementia garden) | Safety Being away Compatibility Social context | Ground cover Water Extent Fascination Compatibility | Exploration of how the design of a restorative garden can support older people with dementia by reducing attention fatigue | ||

| Neale, Aspinall, Roe, et al. (2020) [72] | United Kingdom | Empirical study Quantitative ART and SRT | In situ study Brain activity (EEG) | Alpha waves (relaxation) Beta waves (attention) | N = 95 Aged between 65–92 years | Healthy adults were able to walk unassisted for at least 15 min. No cognitive deficits (MMSE scores). | Nature and urban environment (Urban green space, quiet urban area, busy street) | Fascination Familiarity | Experimental study to look at brain activity in older people while walking in urban environments. | |

| Ottosson, Grahn (2005) [52] | Sweden | Empirical study Quantitative ART and SRT | In situ study Attention tests Physiological measures Questionnaire | Necker cube pattern control test Digit span forward Digit span backwards Symbol digit modalities test Blood pressure Heart rate Pulse rate Preference | N = 15 M = 85 years | Mostly women. Four are in a wheelchair. All need care. Living in a care home. | Nature environment (Shared garden of Geriatric care centre) | Safety Compatibility Social context | Deflected vista Fascination Familiarity | Experimental study to measure restoration in care home residents. |

| Ottosson, Grahn (2006) [51] | Sweden | Empirical study Mixed-method ART and SRT | In situ study Attention tests Physiological measures Questionnaire | Necker cube pattern control test Digit span forward Digit span backwards Symbol digit modalities test Blood pressure Pulse rate Degree to which they felt at home Social climate Activities Mental energy Physical condition | N = 15 Age between 67–97 years | Almost all females. Four were in a wheelchair. | Urban environment (Retirement home) | Safety Social context | Experimental study to measure restoration in care home residents. | |

| Qiu, Chen, Gao (2021) [59] | China | Empirical study Quantitative ART | Lab study Photo evaluation Questionnaire | PRS Perceived Sensory Dimensions (PSD) Preferences | N = 300 Aged 60+ years M = 69 years | Male/female was equally divided. No cognitive or communication difficulties. | Nature environment (Botanical garden) | Safety Being away Compatibility Social context | Complexity Ground cover Water Extent (coherence) Fascination Compatibility | Study to measure restoration of older adults when viewing nature images |

| Roe, Roe (2018) [17] | (Not specified) | Literature review Qualitative ART and SRT | Nature and urban environment (Home environment, garden, park, street, outdoor gym, water setting, adventurous environment, farmers market, dementia care centre) | Being away Compatibility Social context | Deflected vista Extent Fascination | Book chapter/review about restorative environments for older adults and how they promote activity | ||||

| Rosenbaum, Sweeney, Windhorst (2009) [53] | United States | Empirical study Quantitative ART | In situ study Questionnaire | Short PRS Place attachment Social support (SSQT) Activities Perceived health status Patronising | N = 90 Age between 60–89 years M = 70 years | Almost all were female participants. Half were married. | Urban environment (Matter’s More Than a Café (MMC)) | Being away Social context | Fascination | Study to get to know if senior café can offer restoration to older adults. Primarily focusing on social context. |

| Rosenbaum, Sweeney, Massiah (2014) [54] | Australia | Empirical study Mixed-method ART | Study 1 In situ study Interview | Analyses of descriptions of interview data using the four ART characteristics. | N = 11 Age between 70–92 years | Male/female was equally divided. Between 2–18 years visitors of the centre. | Urban environment (Senior Centre) | Safety Being away Compatibility Social context | Extent Fascination Compatibility | Study to analyse the restorative potential of senior activity centres—follow-up study. |

| Study 2 In situ study Questionnaire | Short PRS Fatigue (IFS instrument) Quality of Life Mood Attitude Physical strength Mental strength Customer behaviour | N = 85 Age between 60–92 years | 60% female. | |||||||

| Scopelliti, Giuliani (2004) [65] | Italy | Empirical study Mixed-method ART | Real-life study (not in situ) Questionnaire Interview | Questionnaire about the restorative experience (relaxing and exciting) Semi structured interviews about why they would feel restored in a particular situation Moment of restorative experience: weekday, weekend, vacation | N = 22 M = 68.4 years (Compared with larger group N = 67) | Males/females were equally divided. | Nature and urban environments (Participants could suggest their own restorative environments) | Being away Compatibility Social context | Extent Fascination Compatibility | One of the first restorative environment studies with older adults. Studying which restorative places people choose across their lifespan. |

| Scopelliti, Giuliani (2006) [64] | Italy | Empirical study Mixed-method ART | Study 1 Real-life study (not in situ) Interviews | Analyses of descriptions of restorative experiences | N = 48 Aged between 60–85 years M = 70.54 years | Living in an urban setting. Male/female was equally divided. | Nature and urban environments (Participants could suggest their own restorative environments) | Safety Being away Compatibility Social context | Deflected vista Water Extent (coherence and scope) Fascination Familiarity Compatibility | Analyses of restorative experiences of older adults. Follow-up study. |

| Study 2 Real-life study (not in situ) Questionnaire | Italian PRS | N = 192 Aged between 63–78 years M = 68.23 years | Male/female was equally divided. Good health. No physical or cognitive impairments. Almost all participants were married. | |||||||

| Tang, Brown (2006) [89] | Canada | Empirical study Quantitative SRT | In situ study Physiological measures | Blood pressure Heart rate POMS | N = 5 Aged between 77–89 years | All females. Lived in a retirement centre. All completed high school. Caucasian. | Nature and urban environment (View from a window of the retirement home to build environment OR natural landscape) | Quasi-experiment to study the effect of viewing nature landscapes on mental health of older women. | ||

| Travis, McAuley (1998) [50] | United States | Empirical study Qualitative ART | Real-life study (not in situ) Interviews | Analyses of descriptions of restorative experiences Preferences | N = 8 Aged 60+ years | Admitted to care facility after hip surgery. | Nature and urban environments (Participants could suggest their own restorative environments) | Compatibility Social context | Experiment to check if restorative experience can support hip surgery rehabilitation with older adults. | |

| Twedt, Rainey, Proffitt (2016) [90] | United States | Empirical study Quantitative ART | Lab study Photo evaluation Questionnaire | PRS Visual appeal Naturalness Formal/informal garden | N = 295 Aged between 18–82 years (Compared within age groups) | Mainly Caucasian. More woman. College education. | Nature environment (Formal and informal shared gardens) | The study compares formal and informal garden designs on their restorative effect. | ||

| Weber, Trojan (2018) [20] | (Not specified) | Systematic literature review Quantitative ART and SRT | Urban environments (Various e.g., street, museum) | Being away Compatibility Social context | Extent Fascination Familiarity | Literature review of studies that studied urban restorative environments. | ||||

| Yu, Lee, Lu, et al. (2020) [68] | Taiwan | Empirical study Mixed-method ART and SRT | Lab study Virtual reality Physiological measures Attention tasks Questionnaire | Heart rate Systolic and diastolic blood pressure Activity level of (para)sympathetic nervous system RCS SART POMS Descriptions of VR-experience | N = 9 Aged 65+ years (Compared within larger sample N = 34) | Most female. Healthy participants with no neuropsychiatric disorders, cardiovascular diseases, or cognition disorders of specific visual and hearing problems. | Nature and urban environments (Nature reserve park, busy urban streets) | Experimental study measures restorative effects on older adults while viewing virtual nature. Compare older and middle-aged adults. | ||

| Zhao, Li, Zhu, Ge (2020) [91] | China | Empirical study Quantitative ART | In situ study Questionnaire | PRSS Stress level (in last month) Comfort of soundscape Intensity of soundscape Preference of soundscape | N = 29 Aged 60+ years (Compared within larger sample N = 240) | Male/female evenly distributed. | Nature environment (Urban park) | Studying the effect of birdsong soundscape on the restorative potential of urban parks. |

References

- WHO. Ageing and Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health (accessed on 12 July 2023).

- van Hees, S. The Making of Ageing-in-Place Perspectives on a Dutch Social Policy. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Maastricht, Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- van Helder, L.; Bos, W.; Bleijenberg, N.; van Eijck, J.; de Jager, H.; Klomp, M.; de Langen, M.; Minkman, M.; Pieterse, T.; van Rixtel, M.; et al. Oud En Zelfstandig in 2030 Een Reisadvies; De Rijksoverheid: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Global Strategy and Action Plan on Ageing and Health; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cutchin, M.P. The Process of Mediated Aging-in-Place; a Theoretically Empirically Based Model. Soc. Sci. Med. 2003, 57, 1077–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwarsson, S.; Stahl, A. Accessibility, Usability and Universal Design-Positioning and Definition of Concepts Describing Person-Environment Relationships. Disabil. Rehabil. 2003, 25, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, H.-W.; Oswald, F. Environmental Perspectives on Aging. In The Sage Handbook of Social Gerontology; Dannefer, D., Phillipson, C., Eds.; Sage Publication Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010; pp. 111–124. [Google Scholar]

- Yasamy, M.T.; Dua, T.; Harper, M.; Saxena, S. Mental Health of Older Adults, Addressing a Growing Concern; Academia: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- PAHO/WHO. Seniors and Mental Health. Available online: https://www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=9877:seniors-mental-health&Itemid=40721&lang=en (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- Garin, N.; Olaya, B.; Miret, M.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L.; Power, M.; Bucciarelli, P.; Haro, J.M. Built Environment and Elderly Population Health: A Comprehensive Literature Review. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 2014, 10, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, G.W. The Built Environment and Mental Health. J. Urban Health 2003, 80, 536–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markevych, I.; Schoierer, J.; Hartig, T.; Chudnovsky, A.; Hystad, P.; Dzhambov, A.M.; de Vries, S.; Triguero-Mas, M.; Brauer, M.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J.; et al. Exploring Pathways Linking Greenspace to Health: Theoretical and Methodological Guidance. Environ. Res. 2017, 158, 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartig, T.; Mitchell, R.; De Vries, S.; Frumkin, H. Nature and Health. Annu. Rev. of Public Health 2014, 35, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T. Restoration in Nature: Beyond the Conventional Narrative. In Nature and Psychology. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation; Schutte, A.R., Torquati, J.C., Stevens, J.R., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 67, pp. 89–151. ISBN 9783030690205. [Google Scholar]

- Hartig, T. Three Steps to Understanding Restorative Environments as Health Resources. In Open space: People space; Ward Thompson, C., Travlou, P., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2007; pp. 163–179. ISBN 9780203961827. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, J.; Wood, L.J.; Knuiman, M.; Giles-Corti, B. Quality or Quantity? Exploring the Relationship between Public Open Space Attributes and Mental Health in Perth, Western Australia. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 74, 1570–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, J.; Roe, A. Restorative Environments and Promoting Physical Activity Among Older People. In The Palgrave Handbook of Ageing and Physical Activity Promotion; Nyman, S.R., Barker, A., Haines, T., Horton, K., Musselwhite, C., Peeters, G., Victor, C.R., Wolff, J.K., Eds.; Palgrave Mcmillan: Cham, Switserland, 2018; pp. 467–483. ISBN 9783319712918. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, T.; Kerr, J.; Schipperijn, J. Associations between Neighborhood Open Space Features and Walking and Social Interaction in Older Adults-a Mixed Methods Study. Geriatrics 2019, 4, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Wang, J.; Qin, B. Quantity or Quality? Exploring the Association between Public Open Space and Mental Health in Urban China. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 213, 104–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, A.M.; Trojan, J. The Restorative Value of the Urban Environment: A Systematic Review of the Existing Literature. Environ. Health Insights 2018, 12, 1178630218812805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, D.A. Attentional Demands and Restorative Activities: Do They Influence Directed Attention among the Elderly. Ph.D. Thesis, Univeristy of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Fumagalli, N.; Fermani, E.; Senes, G.; Boffi, M.; Pola, L.; Inghilleri, P. Sustainable Co-Design with Older People: The Case of a Public Restorative Garden in Milan (Italy). Sustainability 2020, 12, 3166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, R.C.; Straus, E.; Campbell, L.M. Stress, Mental Health, and Aging. In Handbook of Mental Health and Aging; Hantke, N., Etkin, A., O’Hara, R., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 37–58. ISBN 9780128001363. [Google Scholar]

- Fleury-Bahi, G.; Pol, E.; Navarro, O. Handbook of Environmental Psychology and Quality of Life; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Collado, S.; Staats, H.; Corraliza, J.A.; Hartig, T. Restorative Environments and Health. In Handbook of Environmental Psychology and Quality of Life Research; Enric, G.F., Oscar, P., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; p. 574. ISBN 9783319314143. [Google Scholar]

- Husser, E.K.; Roberto, K.A.; Allen, K.R. Nature as Nurture: Rural Older Women’s Perspectives on the Natural Environment. J. Women Aging 2020, 32, 44–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabisch, N.; Püffel, C.; Masztalerz, O.; Hemmerling, J.; Kraemer, R. Physiological and Psychological Effects of Visits to Different Urban Green and Street Environments in Older People: A Field Experiment in a Dense Inner-City Area. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 207, 103998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarosz, E. Direct Exposure to Green and Blue Spaces Is Associated with Greater Mental Wellbeing in Older Adults. J. Aging Environ. 2022, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornioli, A.; Parkhurst, G.; Morgan, P.L. Psychological Wellbeing Benefits of Simulated Exposure to Five Urban Settings: An Experimental Study from the Pedestrian’s Perspective. J. Transp. Health 2018, 9, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Li, X.; Luo, H.; Fu, E.K.; Ma, J.; Sun, L.X.; Huang, Z.; Cai, S.Z.; Jia, Y. Empirical Study of Landscape Types, Landscape Elements and Landscape Components of the Urban Park Promoting Physiological and Psychological Restoration. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 48, 126488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Qi, J.; Li, W.; Dong, J.; van den Bosch, C.K. The Contribution to Stress Recovery and Attention Restoration Potential of Exposure to Urban Green Spaces in Low-Density Residential Areas. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Qu, H.; Ma, Y.; Wang, K.; Qu, H. Restorative Benefits of Urban Green Space: Physiological, Psychological Restoration and Eye Movement Analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 301, 113930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San-Juan, C.; Subiza-Pérez, M.; Vozmediano, L. Restoration and the City: The Role of Public Urban Squares. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boffi, M.; Pola, L.G.; Fermani, E.; Senes, G.; Inghilleri, P.; Piga, B.E.A.; Stancato, G.; Fumagalli, N. Visual Post-Occupancy Evaluation of a Restorative Garden Using Virtual Reality Photography: Restoration, Emotions, and Behavior in Older and Younger People. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 927688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornioli, A.; Subiza-Pérez, M. Restorative Urban Environments for Healthy Cities: A Theoretical Model for the Study of Restorative Experiences in Urban Built Settings. Landsc. Res. 2022, 48, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, J.; McCay, L. Restorative Cities. Urban Design for Mental Health and Wellbeing; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping Studies: Advancing the Methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joye, Y.; Van Den Berg, A.E. Restorative Environments. In Environmental psychology. An introduction; Steg, L., Van der Berg, A.E., De Groot, J., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2012; pp. 55–66. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, R.S. Aesthetic and Affective Response to Natural Environment. In Behavior and the Natural Environment; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1983; pp. 85–125. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, R.S.; Simonst, R.F.; Lositot, B.D.; Fioritot, E.; Milest, M.A.; Zelsont, M. Stress Recovery during Exposure to Natural and Urban Environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1991, 11, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S. The Restorative Benefits of Nature: Toward an Integrative Framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staats, H. Restorative Environments. In The Oxford Handbook of Environmental and Conservation Psychology; Clayton, S.D., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMAScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. Pensions at a Glance 2021: OECD and G20 Indicators. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/304a7302-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/304a7302-en#:~:text=In%202020%2C%20the%20OECD%20average,%2C%20for%20men%20only%2C%20Israel (accessed on 5 September 2023).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwuegbuzie, A.J.; Leech, N.L.; Collins, K.M.T. The Qualitative Report The Qualitative Report Qualitative Analysis Techniques for the Review of the Literature Qualitative Analysis Techniques for the Review of the Literature. Qual. Rep. 2012, 17, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, B.; Scherman, V. Computer-Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis Software for Scoping Reviews: A Case of ATLAS.Ti. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2021, 20, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travis, S.S.; McAuley, W.J. Mentally Restorative Experiences Supporting Rehabilitation of High Functioning Elders Recovering from Hip Surgery. J. Adv. Nurs. 1998, 27, 977–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottosson, J.; Grahn, P. Measures of Restoration in Geriatric Care Residences: The Influence of Nature on Elderly People’s Power of Concentration, Blood Pressure and Pulse Rate. J. Hous. Elder. 2006, 19, 227–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottosson, J.; Grahn, P. A Comparison of Leisure Time Spent in a Garden with Leisure Time Spent Indoors: On Measures of Restoration in Residents in Geriatric Care. Landsc. Res. 2005, 30, 23–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, M.S. Restorative Servicescapes: Restoring Directed Attention in Third Places. J. Serv. Manag. 2009, 20, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, M.S.; Sweeney, J.C.; Massiah, C. The Restorative Potential of Senior Centers. Manag. Serv. Qual. 2014, 24, 363–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlay, J.; Franke, T.; Mckay, H.; Sims-Gould, J. Health & Place Therapeutic Landscapes and Wellbeing in Later Life: Impacts of Blue and Green Spaces for Older Adults. Health Place 2015, 34, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, D.A. Perceived Barriers to Participation in Mentally Restorative Activities by Community-Dwelling Elders. Act. Adapt. Aging 2005, 29, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, M.L.; Ou, S.J.; Heng Hsieh, C.; Li, Z.; Ko, C.C. Effects of Garden Visits on People with Dementia: A Pilot Study. Dementia 2020, 19, 1009–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, D.A.; Von Sadovszky, V. Restorative Activities of Community-Dwelling Elders. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2004, 26, 381–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Chen, Q.; Gao, T. The Effects of Urban Natural Environments on Preference and Self-Reported Psychological Restoration of the Elderly. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, H.; Yang, Z.; Bi, S.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, G. The Effects of Green and Urban Walking in Different Time Frames on Physio-Psychological Responses of Middle-Aged and Older People in Chengdu, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, K.D. Restorative Dementia Gardens: Exploring How Design May Ameliorate Attention Fatigue. J. Hous. Elder. 2007, 21, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassarino, M.; Tuohy, I.C.; Setti, A. Sometimes Nature Doesn’t Work: Absence of Attention Restoration in Older Adults Exposed to Environmental Scenes. Exp. Aging Res. 2019, 45, 372–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Oh, W.; Ooka, R.; Wang, L. Effects of Environmental Features in Small Public Urban Green Spaces on Older Adults’ Mental Restoration: Evidence from Tokyo. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scopelliti, M.; Giuliani, M.V. Restorative Environments in Later Life: An Approach to Well-Being from the Perspective of Environmental Psychology. J. Hous. Elder. 2006, 19, 203–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scopelliti, M.; Giuliani, V. Choosing Restorative Environments across the Lifespan: A Matter of Place Experience. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, B.; McIntosh, J.; Kershaw, C. Healing Spaces: Improving Health and Wellbeing for the Elderly through Therapeutic Landscape Design. Int. J. Arts Humanit. 2019, 3, 20–34. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, J.L.; Thirlaway, K.J.; Backx, K.; Clayton, D.A. Allotment Gardening and Other Leisure Activities for Stress Reduction and Healthy Aging. Horttechnology 2011, 21, 577–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.P.; Lee, H.Y.; Lu, W.H.; Huang, Y.C.; Browning, M.H.E.M. Restorative Effects of Virtual Natural Settings on Middle-Aged and Elderly Adults. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 56, 126863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhai, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Newman, G.; Wang, D. Subtypes of Park Use and Self-Reported Psychological Benefits among Older Adults: A Multilevel Latent Class Analysis Approach. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 190, 103605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boffi, M.; Pola, L.; Fumagalli, N.; Fermani, E.; Senes, G.; Inghilleri, P. Nature Experiences of Older People for Active Ageing: An Interdisciplinary Approach to the Co-Design of Community Gardens. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 702525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, M.S.; Sweeney, J.C.; Windhorst, C. The Restorative Qualities of an Activity-Based, Third Place Café. Sr. Hous Care J. 2009, 17, 39–54. [Google Scholar]

- Neale, C.; Aspinall, P.; Roe, J.; Tilley, S.; Mavros, P.; Cinderby, S.; Coyne, R.; Thin, N.; Ward Thompson, C. The Impact of Walking in Different Urban Environments on Brain Activity in Older People. Cities Health 2020, 4, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.S.; Jeong, S.J.; Kim, J.S.; Yoo, E. The Role of Visitor’s Positive Emotions on Satisfaction and Loyalty with the Perception of Perceived Restorative Environment of Healing Garden. J. People Plants Environ. 2020, 23, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berto, R. Assessing the Restorative Value of the Environment: A Study on the Elderly in Comparison with Young Adults and Adolescents. Int. J. Psychol. 2007, 42, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yuan, Y. The Neighborhood Effect of Exposure to Blue Space on Elderly Individuals’ Mental Health: A Case Study in Guangzhou, China. Health Place 2020, 63, 102348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansen, D.A. Mentally Restorative Activities and Daily Functioning Among Community-Dwelling Elders. Act. Adapt. Aging 2008, 32, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabisch, N.; van den Bosch, M.; Lafortezza, R. The Health Benefits of Nature-Based Solutions to Urbanization Challenges for Children and the Elderly—A Systematic Review. Environ. Res. 2017, 159, 362–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staats, H.; Hartig, T. Alone or with a Friend: A Social Context for Psychological Restoration and Environmental Preferences. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jandackova, V.K.; Scholes, S.; Britton, A.; Steptoe, A. Are Changes in Heart Rate Variability in Middle-Aged and Older People Normative or Caused by Pathological Conditions? Findings From a Large Population-Based Longitudinal Cohort Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2016, 5, e002365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moor, N.; Mohammadi, M. Grey Smart Societies: Supporting the Social Inclusion of Older Adults by Smart Spatial Design. In Data-Driven Multivalence in the Built Environment; Biloria, N., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 157–180. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton, M.P.; Nahemow, L. Ecology and the Aging Process. In The Psychology of Adult Development and Aging; Eisendorfer, C., Lawton, M.P., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1973; pp. 619–674. [Google Scholar]

- Wahl, H.-W.; Oswald, F. Theories of Environmental Gerontology: Old and New Avenues for Person-Environmental Views of Aging. In Handbook of Theories of Aging; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 621–641. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, C.A.; Smith, T.W.; Henry, N.J.M.; Pearce, G. A Developmental Approach to Psychosocial Risk Factors in Successful Aging. In Handbook of Health Psychology and Aging; Aldwin, C.M., Park, C.L., Spiro, A., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dannefer, D.; Settersten, R.A., Jr. The Study of Life Course: Implications for Social Gerontology. In The SAGE Handbook of Social Gerontology; Dannefer, D., Philipson, C., Eds.; SAGE: London, UK, 2010; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, M.; Ding, D.; Bauman, A.; Negin, J.; Phongsavan, P. Social Engagement Pattern, Health Behaviors and Subjective Well-Being of Older Adults: An International Perspective Using WHO-SAGE Survey Data. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.H.M.; Qiu, L.; Esposito, G.; Mai, K.P.; Tam, K.P.; Cui, J. Nature in Virtual Reality Improves Mood and Reduces Stress: Evidence from Young Adults and Senior Citizens. Virtual Real. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsadek, M.; Shao, Y.; Liu, B. Benefits of Indirect Contact with Nature on the Physiopsychological Well-Being of Elderly People. Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2021, 14, 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamble, K.R.; Howard, J.H.; Howard, D.V. Not Just Scenery: Viewing Nature Pictures Improves Executive Attention in Older Adults. Exp. Aging Res. 2014, 40, 513–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, J.W.; Brown, R.D. The Effect of Viewing a Landscape on Physiological Health of Elderly Women. J. Hous. Elder. 2006, 1, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twedt, E.; Rainey, R.M.; Proffitt, D.R. Designed Natural Spaces: Informal Gardens Are Perceived to Be More Restorative than Formal Gardens. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Li, H.; Zhu, X.; Ge, T. Effect of Birdsong Soundscape on Perceived Restorativeness in an Urban Park. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Theory | Resource Category | Antecedent Condition | Features of P-E Transactions That Permit Restoration | Features of P-E Transactions That Promote Restoration | Outcomes That Can Reflect on Restoration | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stress Reduction Theory (SRT) | Ability to mobilise for action | Psychophysiological stress | The apparent absence of uncontrollable threat | Perception of natural contents | Moderate levels of complexity | More positive self-reported affect, lower blood pressure and cortisol levels | |

|  |  | |||||

| In view of a threatful event, feelings of safety need to be encouraged to permit the restoration process. | Scenes with water enhance environmental quality. | Describes the number of separated elements in an environment and the balance between structured and unstructured elements. | |||||

| Gross structure | Other visual stimulus attributes | ||||||

|  | ||||||

| The environment needs to give structured information for orientation, for example, a clear focal point. | The line of sight is deflected, hiding what could be lying behind this raises feelings of interest and curiosity. Impacts feelings of spaciousness | ||||||

| Attention Restoration Theory (ART) | Ability to direct attention | Directed attention fatigue | Being away | Compatibility | Fascination | Extent | Improved performance on standardised tests of cognitive abilities |

|  |  |  | ||||

| Escape (physically or mentally) from everyday routine pressures and obligations. | The perceived fit between the environment and the individual needs and inclinations. | The environment’s capability to involuntarily catch one’s attention and not demand mental effort. | Refers to properties of connectedness. The environment feels like a whole (coherence) and promises to engage one’s mind (scope). | ||||

| Compatibility | |||||||

| |||||||

| The way that an environment enables people to experience restorative activities. | |||||||

| Psychological restoration | Restoration likelihood; Restorative experiences; Restorative potential; Perceived restoration; Restorative environment; Attention restoration; Stress |

| Older population | Elderly; Older adult; Third age; Fourth age; Life span; Life course; Old people; Elder; Age differences; Senior; Older individuals |

| Method | Standardisation on psychological restoration measures for older adults. |

| Research the compatibility of physiological measures and attention tests on older populations. | |

| Individual and generational differences | More research is needed with a variety of older participants, such as older old individuals, people with cognitive disabilities or different cultural backgrounds. |

| Features of person-environment transaction | Further research on the permitting and promoting features proposed in the general theory and how they are applicable to older populations. |

| Investigation of additional features (e.g., being with and familiarity) and their influence on the psychological restoration process for older adults. | |

| Type of environment | Research the restorative potential of accessible environments close to older adults’ homes (for example, neighbourhood open spaces). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Grave, A.J.J.; Neven, L.; Mohammadi, M. Elucidating and Expanding the Restorative Theory Framework to Comprehend Influential Factors Supporting Ageing-in-Place: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6801. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20186801

Grave AJJ, Neven L, Mohammadi M. Elucidating and Expanding the Restorative Theory Framework to Comprehend Influential Factors Supporting Ageing-in-Place: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(18):6801. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20186801

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrave, Anne Johanna Jacoba, Louis Neven, and Masi Mohammadi. 2023. "Elucidating and Expanding the Restorative Theory Framework to Comprehend Influential Factors Supporting Ageing-in-Place: A Scoping Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 18: 6801. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20186801

APA StyleGrave, A. J. J., Neven, L., & Mohammadi, M. (2023). Elucidating and Expanding the Restorative Theory Framework to Comprehend Influential Factors Supporting Ageing-in-Place: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(18), 6801. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20186801