A Survey of Vaping Use, Perceptions, and Access in Adolescents from South-Central Texas Schools

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Data Collection Methods

2.3. Sample Characteristics

2.4. Survey Administration

2.5. Ethical Considerations

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

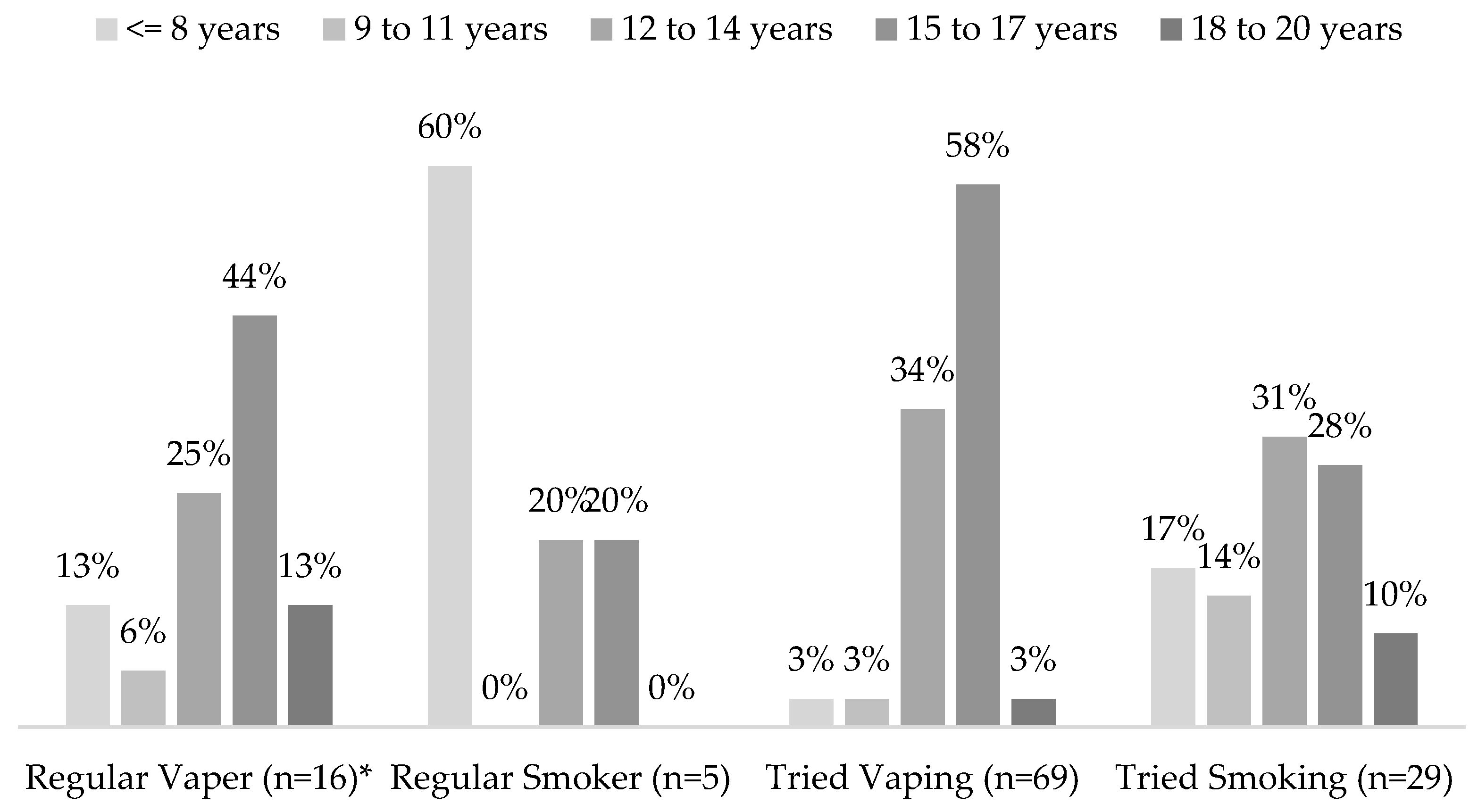

3.1. Baseline Characteristics and Vape Use

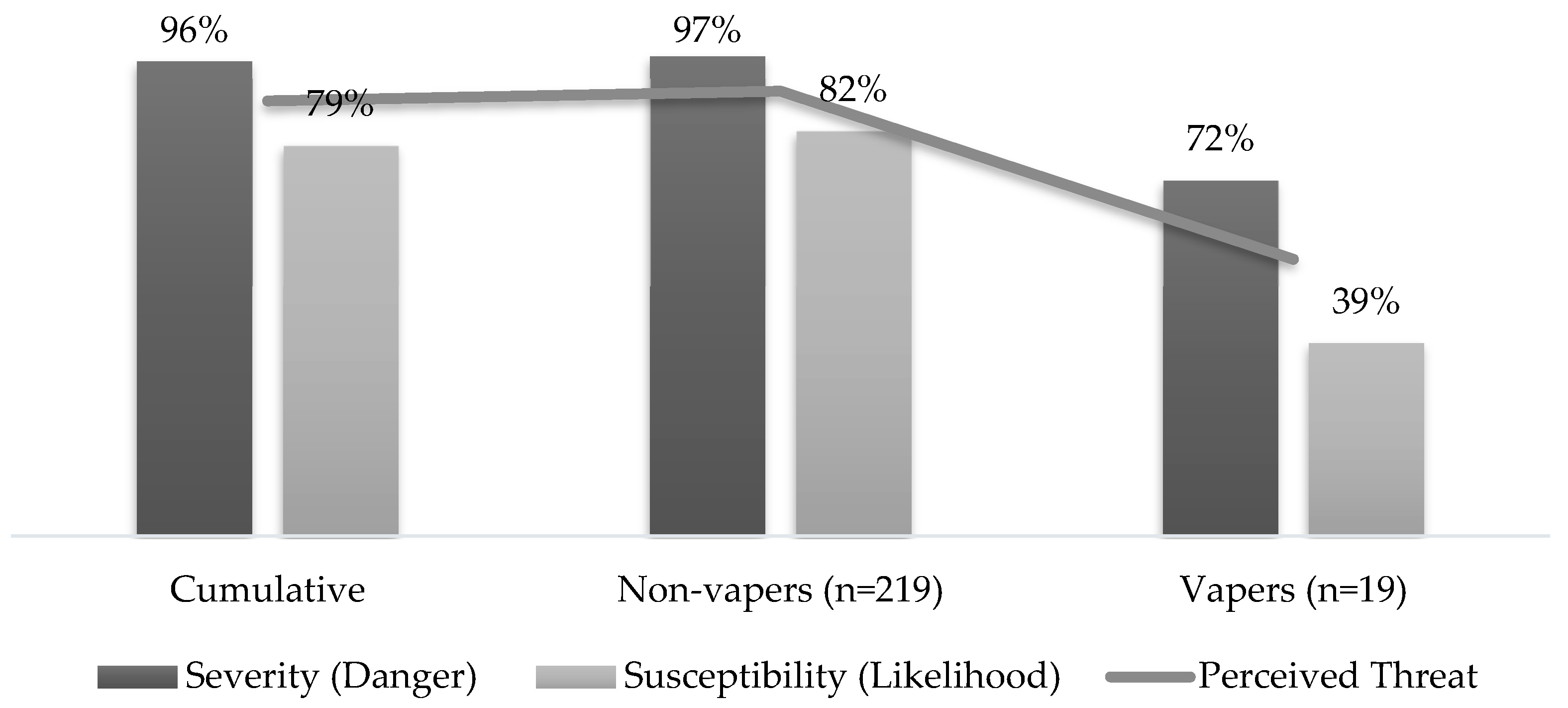

3.2. Perceptions

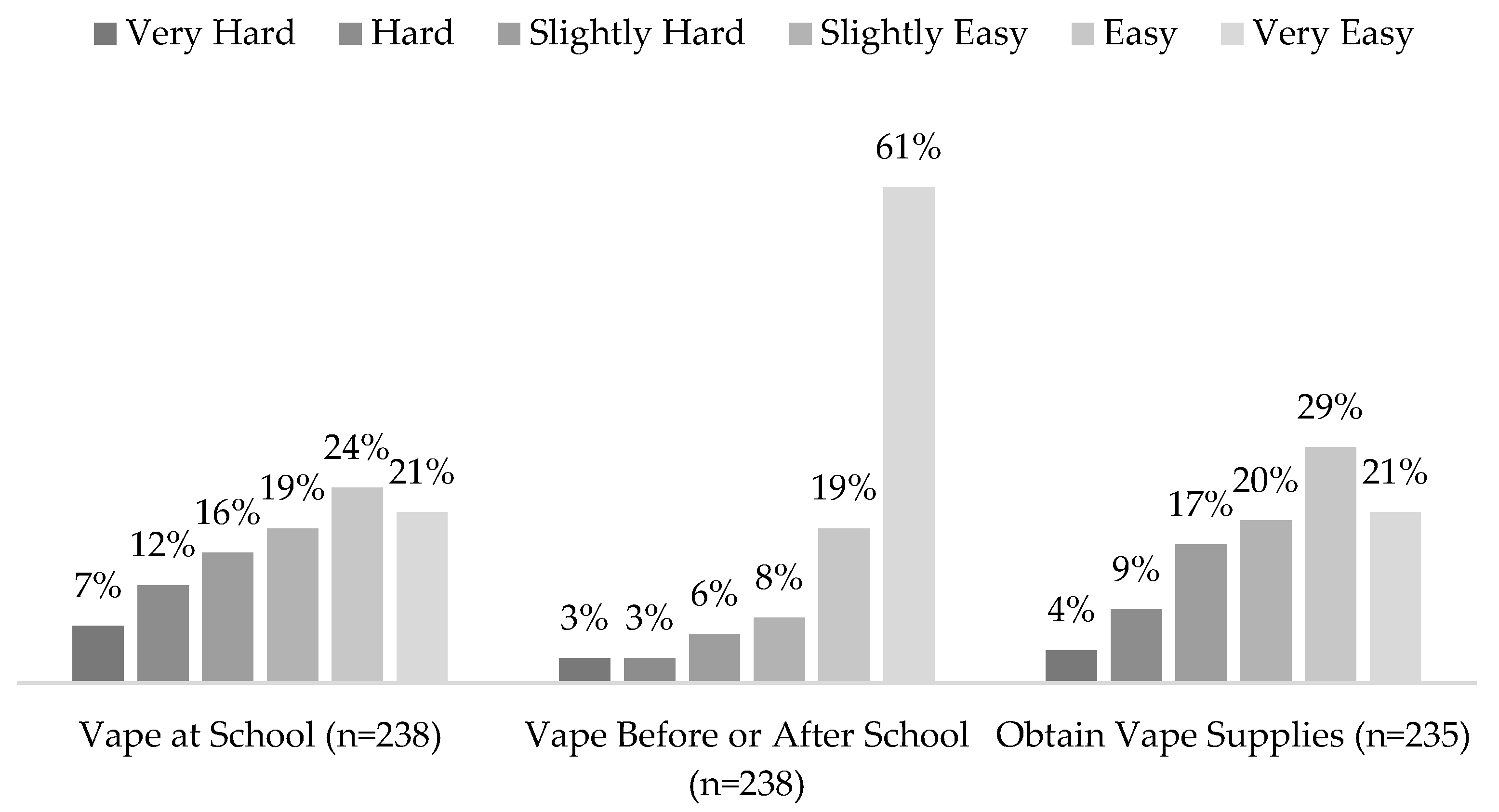

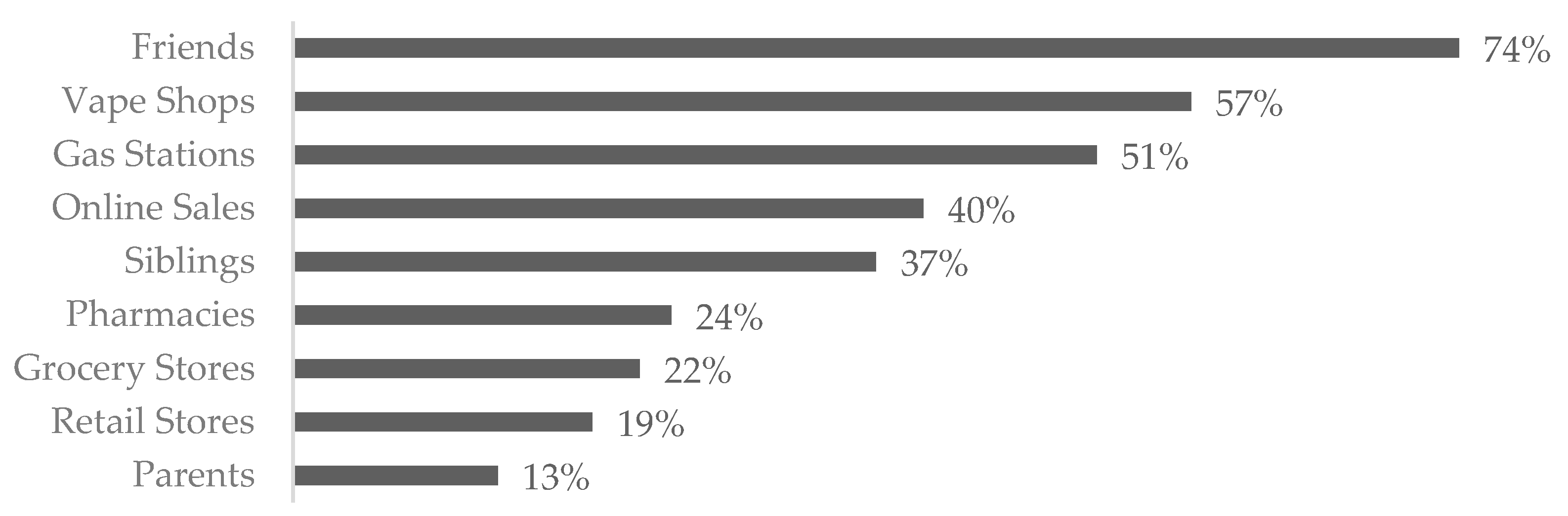

3.3. Access

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dinardo, P.; Rome, E.S. Vaping: The new wave of nicotine addiction. Cleve Clin. J. Med. 2019, 86, 789–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E-Cigarette at the Point of Sale. Counter Tabacco.org 2020. Available online: https://countertobacco.org/resources-tools/evidence-summaries/e-cigarettes-at-the-point-of-sale/ (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA): Reducing Vaping among Youth and Young Adults; SAMHSA Publication No. PEP20-06-01-003; National Mental Health and Substance Use Policy Laboratory, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Rockville, MD, USA, 2020. Available online: https://www.samhsa.gov/resource/ebp/reducing-vaping-among-youth-young-adults (accessed on 12 September 2023).

- Miech, R.; Johnston, L.; O’Malley, P.M.; Bachman, J.G.; Patrick, M.E. Trends in adolescent vaping, 2017–2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1490–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, D.T.; E Warner, K.; Cummings, K.M.; Hammond, D.; Kuo, C.; Fong, G.T.; Thrasher, J.F.; Goniewicz, M.L.; Borland, R. Examining the relationship of vaping to smoking initiation among US youth and young adults: A reality check. Tob. Control 2019, 28, 629–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doran, N.; Myers, M.G.; Correa, J.; Strong, D.R.; Tully, L.; Pulvers, K. Marijuana use among young adult non-daily cigarette smokers over time. Addict. Behav. 2019, 95, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowitt, S.D.; Osman, A.; Meernik, C.; A Zarkin, G.; Ranney, L.M.; Martin, J.; Heck, C.; Goldstein, A.O. Vaping cannabis among adolescents: Prevalence and associations with tobacco use from a cross-sectional study in the USA. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e028535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynn, R.S.R.; Galinkin, J.L. Cannabis, e-cigarettes and anesthesia. Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 2020, 33, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavala-Arciniega, L.; Lozano, P.; Kollath-Cattano, C.; Gutierrez-Torres, D.S.; Arillo-Santillán, E.; Barrientos-Gutiérrez, I.; Hardin, J.W.; Thrasher, J.F. E-cigarette use frequency and motivations among current users in middle school. Drug Alcohol. Depend. 2019, 204, 107585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernat, D.; Gasquet, N.; Wilson, K.O.; Porter, L.; Choi, K. Electronic cigarette harm and benefit perceptions and use among youth. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2018, 55, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzorti, A.; Kapetanstrataki, M.; Evangelopoulou, V.; Behrakis, P. A systematic literature review of e-cigarette-related illness and injury: Not just for the respirologist. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2021. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/surveys/nyts/pdfs/2020/2020-NYTS-Questionnaire-508.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2021).

- Ferrer, R.; Klein, W.M. Risk perceptions and health behavior. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2015, 5, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, K.; Wright, G.C. The usual suspects: Do risk tolerance, altruism, and health predict the response to COVID-19? Rev. Econ. Househ. 2020, 18, 1041–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patrick, M.E.; Miech, R.A.; Carlier, C.; O’Malley, P.M.; Johnston, L.D.; Schulenberg, J.E. Self-reported reasons for vaping among 8th, 10th, and 12th graders in the US: Nationally-representative results. Drug Alcohol. Depend. 2016, 165, 275–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villanti, A.C.; Johnson, A.L.; Glasser, A.M.; Rose, S.W.; Ambrose, B.K.; Conway, K.P.; Cummings, K.M.; Stanton, C.A.; Edwards, K.C.; Delnevo, C.D.; et al. Association of flavored tobacco use with tobacco initiation and subsequent use among US youth and adults, 2013-2015. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e1913804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meernik, C.; Baker, H.M.; Kowitt, S.D.; Ranney, L.M.; Goldstein, A.O. Impact of non-menthol flavours in e-cigarettes on perceptions and use: An updated systematic review. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e031598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechner, W.V.; Murphy, C.M.; Colby, S.M.; Janssen, T.; Rogers, M.L.; Jackson, K.M. Cognitive risk factors of electronic and combustible cigarette use in adolescents. Addict. Behav. 2018, 82, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKenzie, J.F.; Neiger, B.L.; Thackeray, R. Planning, Implementing, and Evaluating Health Promotion Programs: A Primer, 7th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE)statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2008, 61, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Minh Duc, N.T.; Luu Lam Thang, T.; Nam, N.H.; Ng, S.J.; Abbas, K.S.; Huy, N.T.; Marušić, A.; Paul, C.L.; Kwok, J.; et al. A Consensus-Based Checklist for Reporting of Survey Studies (CROSS). J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2021, 36, 3179–3187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Texas School Survey (TSS). Texas A&M University. 2021. Available online: https://www.texasschoolsurvey.org/Survey01.aspx (accessed on 3 February 2021).

- Monitoring the Future (MTF). Institute for Social Research. 2021. Available online: https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/NAHDAP/series/35 (accessed on 5 February 2021).

- Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2018. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/2019/YRBS_questionnaire_content_1991-2019.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2021).

- National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2019. Available online: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt29393/2019NSDUHFFRPDFWHTML/2019NSDUHFFR1PDFW090120.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2021).

- National Health Interview Survey for Young Adults (NHIS). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/2020nhis.htm (accessed on 7 February 2021).

- Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH). National Institute of Drug Abuse. 2018. Available online: https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/files/NAHDAP/pathstudy/Deliverable%2016.Final_.PATH%20Wave%205%20English%20Youth%20Questionnaire.2018-11-01.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2021).

- Evans-Polce, R.J.; Patrick, M.E.; Lanza, S.T.; Miech, R.A.; O’Malley, P.M.; Johnston, L.D. Reasons for vaping among U.S. 12th graders. J. Adolesc. Health 2018, 62, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepper, J.K.; Coats, E.M.; Nonnemaker, J.M.; Loomis, B.R. How do adolescents get their e-cigarettes and other electronic vaping devices? Am. J. Health Promot. 2019, 33, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamo Region. 2023. Available online: https://comptroller.texas.gov/economy/economic-data/regions/2018/alamo.php#:~:text=Translation%3A&text=The%2019%2Dcounty%20Alamo%20Region,Lavaca%20on%20the%20Gulf%20Coast (accessed on 13 February 2021).

- San Antonio Metro Area Population 1950–2021. Macrotrends. 2021. Available online: https://www.macrotrends.net/cities/23128/san-antonio/population (accessed on 13 February 2021).

- Coleman, B.; Rostron, B.; Johnson, S.E.; Persoskie, A.; Pearson, J.; Stanton, C.; Choi, K.; Anic, G.; Goniewicz, M.L.; Cummings, K.M.; et al. Transitions in electronic cigarette use among adults in the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study, Waves 1 and 2 (2013–2015). Tob. Control 2019, 28, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chulani, V.L.; Gordon, L.P. Adolescent Growth and Development. Prim. Care 2014, 41, 465–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, P.; Arillo-Santillan, E.; Barrientos-Gutierrez, I.; Reynales Shigematsu, L.M.; Thrasher, J.F. E-cigarette social norms and risk perceptions among susceptible adolescents in a country that bans e-cigarettes. Health Educ. Behav. 2019, 46, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, H.; Hao, J.; Catley, D. Vape shop density and socio-demographic disparities: A US census tract analysis. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2017, 19, 1338–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilley, M.; Beno, S. Vaping implications for children and youth. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2020, 32, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaiha, S.M.; Halpern-Felsher, B. Escalating safety concerns are not changing adolescent e-cigarette use patterns: The possible role of adolescent mental health. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 66, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Overall (n = 267) | Students Who Do Not Vape (n = 248) | Students Who Vape (n = 19) * | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | Count | % | Count | % | Count | ||

| Sex | n = 253 | n = 234 | n = 19 | 0.49 | |||

| Female | 61% | 153 | 61% | 143 | 53% | 10 | |

| Male | 40% | 100 | 39% | 91 | 47% | 9 | |

| Age | n = 264 | n = 245 | n = 19 | 0.19 | |||

| 12–14 (Group A) | 14% | 37 | 15% | 37 | 0% | 0 | |

| 15–17 (Group B) | 68% | 179 | 67% | 164 | 79% | 15 | |

| 18–20 (Group C) | 18% | 48 | 18% | 44 | 21% | 4 | |

| Grade | n = 264 | n = 245 | n = 19 | 0.24 | |||

| 12th | 25% | 66 | 25% | 61 | 26% | 5 | |

| 11th | 17% | 46 | 18% | 44 | 11% | 2 | |

| 10th | 24% | 62 | 22% | 53 | 47% | 9 | |

| 9th | 27% | 70 | 27% | 67 | 16% | 3 | |

| 8th | <1% | 2 | <1% | 2 | 0% | 0 | |

| 7th | 2% | 4 | 2% | 4 | 0% | 0 | |

| 6th | 5% | 14 | 6% | 14 | 0% | 0 | |

| Predominant Grades | n = 187 | n = 172 | n = 15 | 0.64 | |||

| A’s | 39% | 72 | 40% | 68 | 27% | 4 | |

| A’s & B’s | 39% | 72 | 38% | 65 | 47% | 7 | |

| Other | 23% | 43 | 23% | 39 | 27% | 4 | |

| Race | n = 184 | n = 169 | n = 15 | 0.42 | |||

| White (non-Hispanic) | 45% | 82 | 44% | 75 | 47% | 7 | |

| White (Hispanic) | 26% | 48 | 26% | 44 | 27% | 4 | |

| Hispanic | 15% | 27 | 16% | 27 | 0% | 0 | |

| Other | 15% | 27 | 14% | 23 | 27% | 4 | |

| Predominant Language | n = 186 | n = 171 | n = 15 | 0.01 | |||

| English | 87% | 162 | 87% | 148 | 93% | 14 | |

| Spanish | 9% | 17 | 10% | 17 | 0% | 0 | |

| Other | 4% | 7 | 4% | 6 | 7% | 1 | |

| Both Parents in Home | n = 187 | n = 172 | n = 15 | 0.69 | |||

| Yes | 75% | 141 | 77% | 132 | 60% | 9 | |

| No | 25% | 46 | 23% | 40 | 40% | 6 | |

| Siblings in Home | n = 185 | n = 170 | n = 15 | 0.04 | |||

| Yes | 76% | 140 | 78% | 132 | 53% | 8 | |

| No | 24% | 45 | 22% | 38 | 47% | 7 | |

| Individual Income | n = 187 | n = 172 | n = 15 | 0.24 | |||

| Yes | 68% | 127 | 67% | 115 | 80% | 12 | |

| No | 32% | 60 | 33% | 57 | 20% | 3 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gilmore, B.A.; Gilmore, C.M.; Reveles, K.R.; Koeller, J.M.; Spoor, J.H.; Flores, B.E.; Frei, C.R. A Survey of Vaping Use, Perceptions, and Access in Adolescents from South-Central Texas Schools. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6766. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20186766

Gilmore BA, Gilmore CM, Reveles KR, Koeller JM, Spoor JH, Flores BE, Frei CR. A Survey of Vaping Use, Perceptions, and Access in Adolescents from South-Central Texas Schools. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(18):6766. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20186766

Chicago/Turabian StyleGilmore, Bretton A., Corbyn M. Gilmore, Kelly R. Reveles, Jim M. Koeller, Jodi H. Spoor, Bertha E. Flores, and Christopher R. Frei. 2023. "A Survey of Vaping Use, Perceptions, and Access in Adolescents from South-Central Texas Schools" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 18: 6766. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20186766

APA StyleGilmore, B. A., Gilmore, C. M., Reveles, K. R., Koeller, J. M., Spoor, J. H., Flores, B. E., & Frei, C. R. (2023). A Survey of Vaping Use, Perceptions, and Access in Adolescents from South-Central Texas Schools. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(18), 6766. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20186766