How Do Young Adult Drinkers React to Varied Alcohol Warning Formats and Contents? An Exploratory Study in France

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How do young adults, who are living in a context where social acceptability of alcohol consumption is high, react to various warning contents and formats?

- Are some warning contents (social risks, short-term risks, etc.) more relevant than others for speaking to young adults?

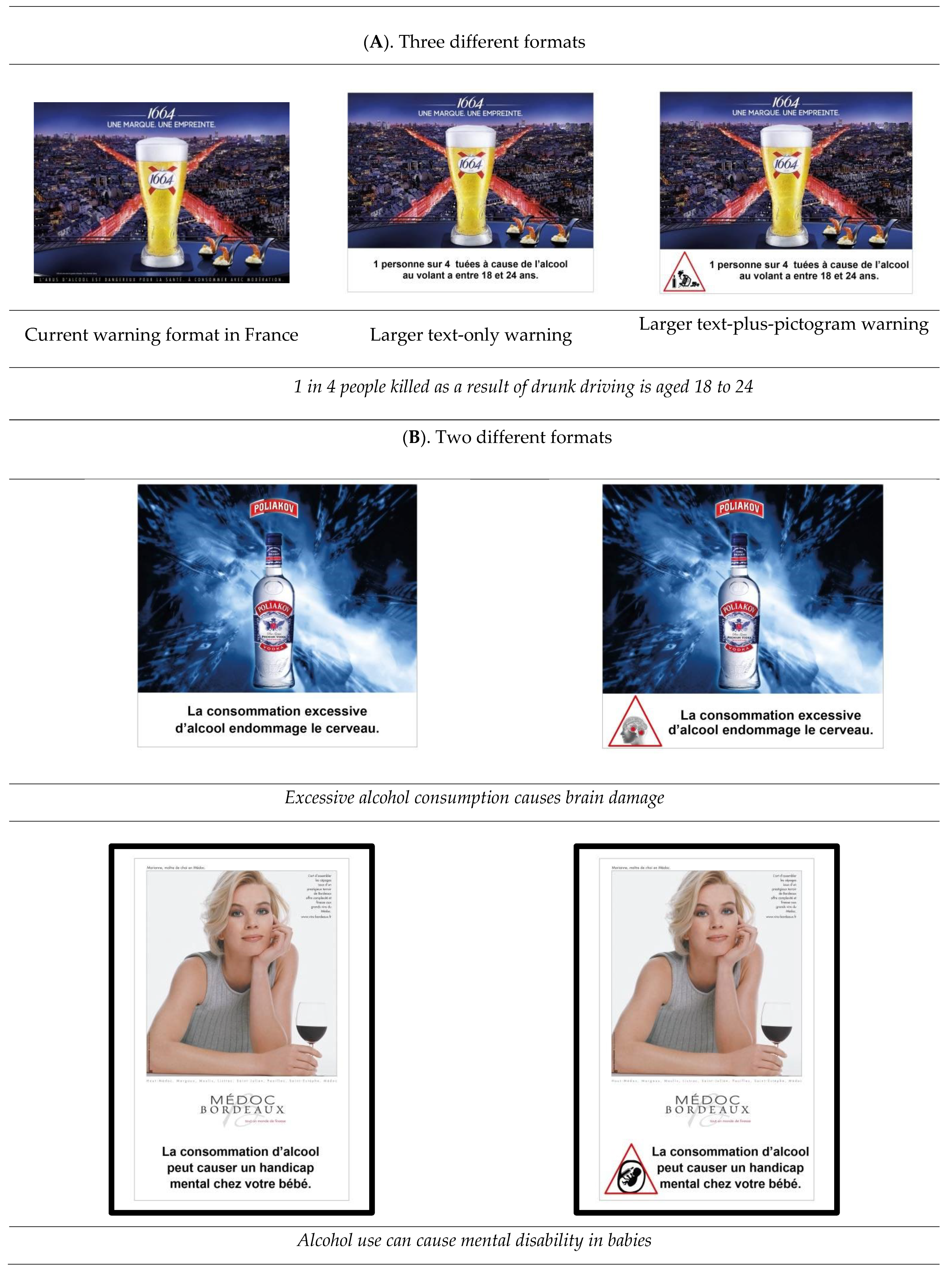

- Is there added benefit in combining a text message with a pictogram?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Recruitment, Sample, and Instruments

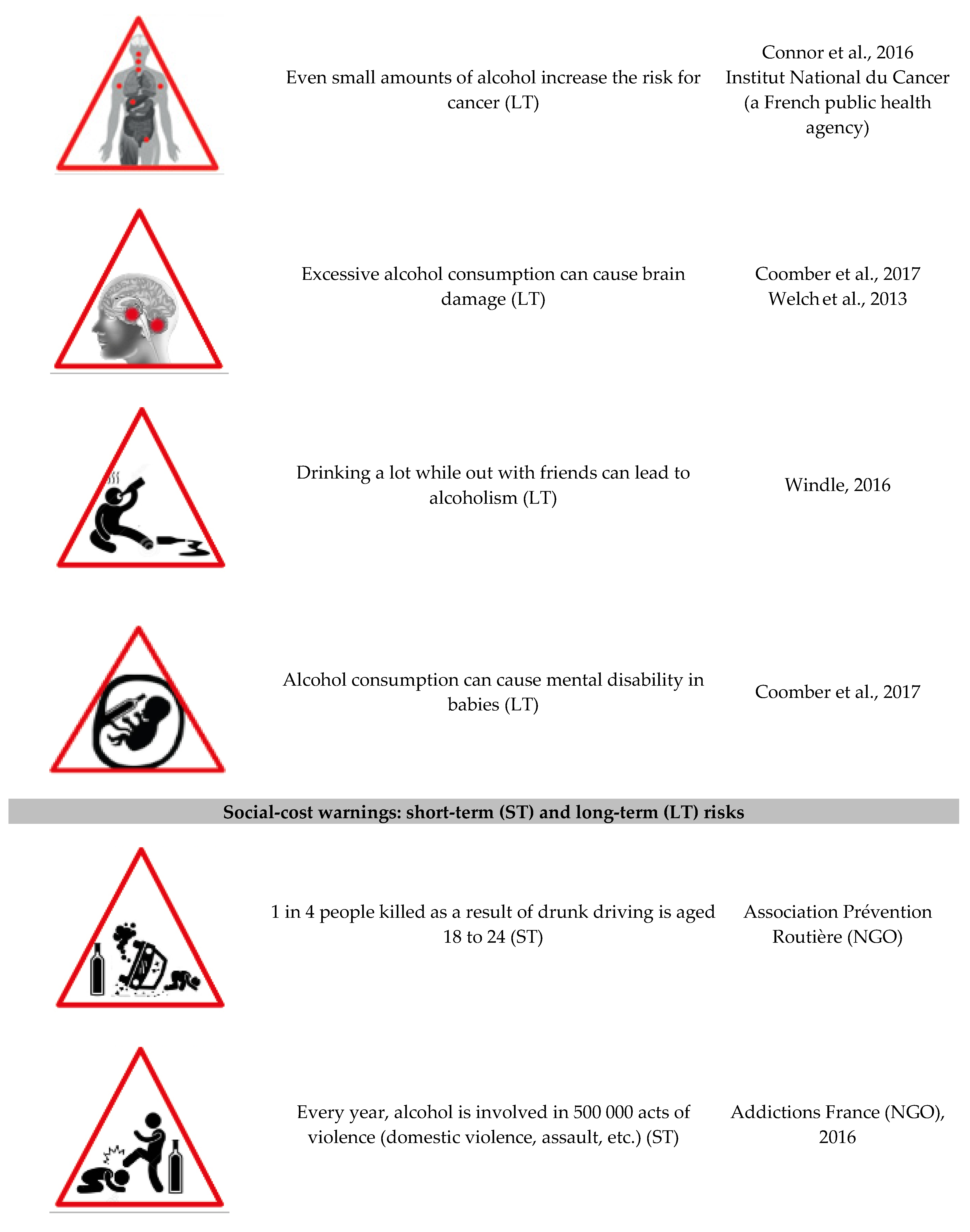

2.2. Study Materials

2.3. Ethics Approval

2.4. Procedure and Analysis

3. Results (The Main Results by Warning Topic Are Summarized in Table 2)

3.1. Overall Reactions to the 12 (Text-Only) New Warning Contents

“… I think it’s a good idea to talk about alcohol coma, and adding the word ‘fatal’ drives the message home even more. It’s true, you can die from that, so I think it’s good idea…”(MMD, 19 (MMD, 19: Male moderate drinker, 19 years old))

“The idea of rotating the messages is important; that way, you get to target everyone”(MHRD, 25 (MHRD, 25: Male high-risk drinker, 25 years old))

“I think we don’t realize what it is: drinking a lot, drinking regularly, or drinking a lot in one session.”(FMD, 18 (FMD, 18: Female moderate drinker, 18 years old))

[risk of cancer] “No, I did not know that. Well, at least in low doses; I know that for an alcoholic, there are necessarily risks, but in low doses…”(FHRD, 25 (FHRD, 25: female high-risk drinker, 25 years old))

“It’s hard to say whether one sentence alone will make you stop drinking.”(FMD, 19)

[risk of alcoholism] “When you’re out with friends, you might drink ‘before’—at the bar or at home— and then in a nightclub, and then during the ‘after’—back at home. But does that make you an alcoholic? No, I don’t think so.”(MHRD, 24)

3.2. Reactions to Health Warnings and Social Warnings

[risk of coma] “Yeah, well yeah, sure it concerns me, uh, you don’t want to try it when you see that, when you see the word ‘fatal’ in any case, it doesn’t make you want to play around with that”(MMD, 24)

[Brain risk] “I find that it’s like there’s a taboo around saying it damages the brain… it’s true that the effects on the brain, you don’t see that used much in alcohol awareness campaigns or when we talk about the risks we might face.”(MMD, 19)

[drunk driving risk] “…it affects me personally, because I lost a friend not long ago because of that.”(MHRD, 20)

[sexual risk] “it could happen to any of us.”(FHRD, 19)

“I’ve never heard that alcohol coma can be fatal. I think that’s fake news.”(FHRD, 19)

“It brings back memories; I have a friend who went into an alcohol coma. It’s very real, and I think there are too many people that might not know that, or are not overly concerned … but it can happen really quickly”(FHRD, 19)

“It can still speak more to young people… I think that after a certain time, you get more careful, you know your limits. For young people who are starting drinking (I would say 14 to 20 years old) and who start drinking way too much sometimes, it might make those specific people think about it a little more.”(FMD, 25)

“It’s extra information, it’ll help me talk about it and avoid drunk driving.”(FMD, 22)

[sexual risk] “…there’s a debate to be had, for sure… like reducing the risk, or at least maybe more often trying to find a ride home, or have a friend drive you home. Or take a cab, or whatever. Maybe think about that already.”(MHRD, 24)

3.3. Reactions to Long-Term and Short-Term Risk Warnings

“Young people don’t think about alcoholism at all, they think that only people older than 40 or 50 can become alcoholics, so I think they just don’t realize.”(MHRD, 20)

“It will mark all pregnant people and make people aware that you can destroy the life of another person, your child.”(MHRD, 20)

[brain risk] “And focusing on the brain is good, because we care about it… So the message will tell everyone about the brain risk, and that’s going to concern more people than alcohol coma.”(MMD, 22)

[risk of cancer] “I say, everything leads to cancer today, like genes… Anyway, we all have cancer-causing genes in our bodies, so basically it all depends on whether you get lucky and those genes are not triggered.”(FHRD, 19)

[risk of isolation] “alcohol connects young people closer to their peers. So, this warning will only be relevant to old people”(MMD, 22)

[risk of alcoholism] “…I don’t think it’s really going to speak to young people either, of if it does, it’ll be more in the long term…”(MHRD, 19)

“In our generation, everyone knows someone who was killed in a road accident. It means something to us.”(FMD, 25)

[risk of coma] “In high school it was all about drinking for the sake of drinking and to get drunk… in high school, it’s about drinking a lot in a short burst, I think that’s what a lot of high-schoolers do.”(FHRD, 19)

3.4. Perceptions of the Three “Innovative” Warnings

[calorie intake] “… I always thought that alcohol didn’t make you fat, I don’t know why […]. When I was dieting, drinking alcohol didn’t stop me.”(MHRD, 20)

[marketing manipulation] “…[this warning] would encourage people to take a more critical look at the advertisements…and be more skeptical about advertising in general… I think that young people, more than other groups, don’t like to feel they are being manipulated.”(FMD, 18)

[calorie intake] “Me personally, it’s going to make me laugh more than anything else: we usually drink a beer with a burger anyway, so we’re blowing the calories.”(FHRD, 20)

[pesticides]: “There are pesticides everywhere, everything is carcinogenic. You might never smoke in your life and still get lung cancer… My mom is in there…”(FHRD, 19)

[pesticides] “This might lead to people maybe drinking more of the organic wines that are certified pesticide free.”(MMD, 22)

[calorie intake] “I know beer makes you fat, you just have to work out to burn off the calories, that’s all…”(MHRD, 24)

“I don’t really get influenced by advertising. So, I mean, I don’t find that advertising by manufacturers manipulates us, because drinking is already part of our culture…”(MHRD, 19)

3.5. The Benefit Value of a Larger Warning Format COMBINED with Pictograms

“For me, a slogan like that, without … without some kind of image or video to support it, it doesn’t have a huge impact…”(MMD, 22)

“You can’t ignore it… I think the idea of the big white banner, which is quite wide, with the pictograms would be very effective if it was put in place.”(FMD, 19)

“We know we would pay more attention to it because, with the pictograms, we’re more vigilant about drugs, advertising, traffic laws, the pictograms speak more.”(MMD, 25)

“[…] the pictogram with the poster is easier to see… you can understand it without necessarily reading the sentence.”(FHRD, 20)

“… It can make people react, even children who see it might think… When you’re a child […] just by seeing the image, children who can’t necessarily read or anything, it can be good.”(FHRD, 25)

“Here it shows you the thing, you know. Someone hitting somebody else; you have heard about it already, but here you’re forced to see it.”(MHRD, 24)

[pregnancy pictogram] “I think it’s really good, because maybe there are a lot of women who think ‘if I drink, it won’t reach the baby, it won’t get through’, but of course it will.”(FHRD, 19)

[pictogram of sexual risk] “It could scare kids away from drinking…”(FMD, 22)

“For me, [the pictogram] is clearer, but a real picture would work better”(FMD, 21)

“…For me, it’s really photos that turn you off… they can disgust you too”(MMD, 22)

“It’s good, it has all the ingredients: the car, the broken bottle, and the person targeted by the message.”(MMD, 22)

| Warnings | Participants’ Reactions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attention * | Cognitive Reactions | Credibility | Intentional Behaviour | |

| Content | ||||

Health warnings

| N/A |

|

|

|

Social-cost warnings

| N/A |

|

|

|

Innovative warnings

| N/A |

|

|

|

| FORMAT | ||||

| Benefit Value of a Larger Warning Format Combined with Pictograms |

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Alcohol Marketing in the WHO European Region: Update Report on the Evidence and Recommended Policy Actions. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/336178 (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Hingson, R.W.; Zha, W. Age of drinking onset, alcohol use disorders, frequent heavy drinking, and unintentionally injuring oneself and others after drinking. Pediatrics 2009, 123, 1477–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statista. Number of Liters of Alcohol Consumed per Capita in Selected European Countries in 2019. Available online: www.statista.com/statistics/755502/alcohol-consumption-in-liters-per-capita-ineu/ (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Bonaldi, C.; Hill, C. La mortalité attribuable à l’alcool en France en 2015. Bull Épidémiol Hebd 2019, 5–6, 97–108. [Google Scholar]

- Richard, J.-B.; Andler, R.; Cogordan, C.; Spilka, S.; Nguyen-Thanh, V.; Groupe Baromètre de Santé Publique France. La consommation d’alcool chez les adultes en France en 2017. Bull Épidémiol Hebd 2019, 5–6, 89–97. [Google Scholar]

- Berdzuli, N.; Ferreira-Borges, C.; Gual, A.; Rehm, J. Alcohol Control Policy in Europe: Overview and Exemplary Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neufeld, M.; Ferreira-Borges, C.; Rehm, J. Implementing Health Warnings on Alcoholic Beverages: On the Leading Role of Countries of the Commonwealth of Independent States. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evin Law République Française. Loi n° 91-32 du 10 janvier 1991 relative à la lutte contre le tabagisme et l’alcoolisme. J. Off. De La République Française 1991, 615–618. [Google Scholar]

- INSERM. Réduction des Dommages Associés à la Consommation D’alcool. In Montrouge: EDP Sciences; Collection Expertise Collective; INSERM: Paris, France, 2021; Volume 253–256, p. 245. Available online: https://www.hal.inserm.fr/inserm-03430421/document (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Gallopel-Morvan, K.; Spilka, S.; Mutatayi, C.; Rigaud, A.; Lecas, F.; Beck, F. France’s Évin Law on the control of alcohol advertising: Content, effectiveness and limitations. Addiction 2017, 112, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millot, A.; Maani, N.; Knai, C.; Petticrew, M.; Guillou-Landréat, M.; Gallopel-Morvan, K. An analysis of how lobbing by the alcohol industry has eroded the French Evin Law since 1991. J. Stud. Alcohol. Drugs 2022, 83, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food & Sens. Dans L’Univers des Chefs. Emmanuel Macron Pour Terre de Vins: “Le vin est un Formidable Atout Pour le Rayonnement de la France”. Food & Sens 2017. Available online: http://foodandsens.com/non-classe/emmanuel-macron-terre-de-vin-vin-formidable-atout-rayonnement-de-france/ (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- La Revue de vin de France. Emmanuel Macron: Un Président qui Aime le vin, qui en Boit, qui en Est Fier! La Revue du vin de France 2022. Available online: https://www.larvf.com/emmanuel-macron-un-president-qui-aime-le-vin-qui-en-boit-qui-en-est-fier,4778341.asp (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Gordon, R.; Heim, D.; MacAskill, S. Rethinking drinking cultures: A review of drinking cultures and a reconstructed dimensional approach. Public Health 2012, 126, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annunziata, A.; Agnoli, L.; Vecchio, R.; Charters, S.; Mariani, A. Health warnings on wine labels: A discrete choice analysis of Italian and French Generation Y consumers. Wine Econ. Policy 2019, 8, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Room, R.; Mäkelä, K. Typologies of the cultural position of drinking. J. Stud. Alcohol. Drugs 2000, 61, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolando, S.; Beccaria, F.; Tigerstedt, C.; Törrönen, J. First drink: What does it mean? The alcohol socialization process in different drinking cultures. Drugs Educ. Prev. Policy 2012, 19, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongenelis, M.I.; Pratt, I.S.; Slevin, T.; Chikritzhs, T.; Liang, W.; Pettigrew, S. The effect of chronic disease warning statements on alcohol-related health beliefs and consumption intentions among at-risk drinkers. Health Educ. Res. 2018, 33, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bocquier, A.; Fressard, L.; Verger, P.; Legleye, S.; Peretti-Watel, P. Alcohol and cancer: Risk perception and risk denial beliefs among the French general population. Eur. J. Public Health 2017, 27, 705–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jané-Llopis, E.; Kokole, D.; Neufeld, M.; Hasan, O.S.M.; Rehm, J. What is the Current Alcohol Labelling Practice in the WHO European Region and What Are Barriers and Facilitators to Development and Implementation of Alcohol Labelling Policy? Health Evidence Network (HEN) Synthesis Report 68; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, J.C.; Netemeyer, R.G.; Durvasula, S. Believability and attitudes toward alcohol warning label information: The role of persuasive communications theory. J. Public Policy Mark. 1990, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, J.C.; Netemeyer, R.G.; Durvasula, S. Effects of consumption frequency on believability and attitudes toward alcohol warning labels. J. Consum. Aff. 1991, 25, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dossou, G.; Gallopel-Morvan, K.; Diouf, J.F. The effectiveness of current French health warnings displayed on alcohol advertisements and alcoholic beverages. Eur. J. Public Health 2017, 26, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Europe’s Beating Cancer Plan: Commission Presents First Country Cancer Profiles under the European Cancer Inequalities Registry 2021. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_23_421 (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Giesbrecht, N.; Reisdorfer, E.; Rios, I. Alcohol Health Warning Labels: A Rapid Review with Action Recommendations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimova, E.D.; Danielle, M. Rapid literature review on the impact of health messaging and product information on alcohol labelling. Drugs Educ. Prev. Policy 2022, 29, 451–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokole, D.; Anderson, P.; Jané-Llopis, E. Nature and potential impact of alcohol health warning labels: A scoping review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.; Moodie, C.; Purves, R.I.; Fitzgerald, N.; Crockett, R. The role of alcohol packaging as a health communications tool: An online cross-sectional survey and experiment with young adult drinkers in the United Kingdom. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2022, 4, 1206–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgenstern, M.; Dumbili, E.W.; Hansen, J.; Hanewinkel, R. Effects of alcohol warning labels on alcohol-related cognitions among German adolescents: A factorial experiment. Addict. Behav. 2021, 117, 106868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, L.B.; Blood, D.J. Caution: Alcohol advertising and the Surgeon General’s alcohol warnings may have adverse effects on young adults. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 1992, 20, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerend, M.A.; Cullen, M. Effects of message framing and temporal context on college student drinking behavior. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 44, 1167–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annunziata, A.; Vecchio, R.; Mariani, A. Alcohol warnings and moderate drinking patterns among Italian university students: An exploratory study. Nutrients 2017, 9, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, S.C.; Gregory, P. The impact of more visible standard drink labelling on youth alcohol consumption: Helping young people drink (ir)responsibly? Drug Alcohol Rev. 2009, 28, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, S.C.; Gregory, P. Health warning labels on alcohol products—The views of Australian University students. Contemp. Drug Probl. 2010, 37, 109–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowden, J.A.; Delfabbro, P.; Room, R.; Miller, C.; Wilson, C. Alcohol consumption and NHMRC guidelines: Has the message got out, are people conforming and are they aware that alcohol causes cancer? Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2014, 38, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, S.; Jongenelis, M.; Chikritzhs, T.; Slevin, T.; Pratt, I.S.; Glance, D.; Liang, W. Developing cancer warning statements for alcoholic beverages. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coomber, K.; Mayshak, R.; Curtis, A.; Miller, P.G. Awareness and correlates of short-term and long-term consequences of alcohol use among Australian drinkers. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2017, 41, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, L.M.; Sara, P.; Edward, S. Exploring responses to differing message content of pictorial alcohol warning labels. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2022, 46, 2200–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallance, K.; Romanovska, I.; Stockwell, T.; Hammond, D.; Rosella, L.; Hobin, E. “We have a right to know”: Exploring consumer opinions on content, design and acceptability of enhanced alcohol labels. Alcohol Alcohol. 2018, 53, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, D.; Moodie, C.; Purves, R.I.; Fitzgerald, N.; Crockett, R. Health information, messaging and warnings on alcohol packaging: A focus group study with young adult drinkers in Scotland. Addict. Res. Theory 2021, 29, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Olmedo, N.; Muciño-Sandoval, K.; Canto-Osorio, F.; Vargas-Flores, A.; Quiroz-Reyes, A.; Sabines, A.; Barrientos-Gutiérrez, T. Warning labels on alcoholic beverage containers: A pilot randomized experiment among young adults in Mexico. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, J.B.; Aasland, O.G.; Babor, T.; De La Fuente, J.R.; Marcus, G. Development of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II. Addiction 1993, 88, 791–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollinger, B. Calorie posting in chain restaurants. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Policy 2011, 3, 91–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, S.; Doxey, J.; Hammond, D. Nutrition labels on pre-packaged foods. Public Health Nutr. 2011, 14, 1496–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R. Altruistic or egoistic: Which value promotes organic food consumption among young consumers? A study in the context of a developing nation. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 33, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, S.M.; Mohammed, N.K. Young consumer’s green purchasing behavior: Opportunities for green marketing. J. Glob. Mark. 2018, 31, 270–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrelly, M.C.; Healton, C.H.; Davis, K.C.; Messeri, P.; Hersey, J.C.; Hayiland, M.L. Getting to the truth: Evaluating national tobacco countermarketing campaigns. Am. J. Public Health 2002, 92, 901–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szybillo, G.; Heslin, R. Resistance to persuasion: Inoculation theory in a marketing context. J. Mark. Res. 1973, 10, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glock, S.; Krolak-Schwerdt, S. Changing outcome expectancies, drinking intentions, and implicit attitudes toward alcohol: A comparison of positive expectancy-related and health-related alcohol warning labels. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 5, 332–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haut Comité de la Santé Publique. Actualité et Dossier en Santé Publique; Alcool et Santé, ADSP No. 90, Match 2015; Haut Comité de la Santé Publique: Paris, France, 2023; p. 10. Available online: https://www.hcsp.fr/explore.cgi/adsp?clef=147 (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Connor, J. Alcohol consumption as a cause of cancer. Addiction 2016, 112, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institut National du Cancer Cited by L’Indépendant on 12 June 2015 in ‘Cancer: Les Dangers de L’alcool, Même à Faible Dose’. Available online: https://www.lindependant.fr/2015/06/12/cancer-les-dangers-de-l-alcool-meme-a-faible-dose,2043742.php (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Welch, K.A.; Carson, A.; Lawrie, S.M. Brain structure in adolescents and young adults with alcohol problems: Systematic review of imaging studies. Alcohol Alcohol. 2013, 48, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Windle, M. Drinking over the lifespan: Focus on early adolescents and youth. Alcohol Res. 2016, 38, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Association Prévention Routière (NGO). Available online: https://www.preventionroutiere.asso.fr/2016/03/31/les-jeunes-et-lalcool/ (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Addictions France. Alcools et Informations des Consommateurs: Une Exigence Legitime, Décryptages 21, December 2016. pp. 6–9. Available online: https://addictions-france.org/ressources/decryptages/ (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Klingemann, H.; Gmel, G.E.D. Mapping the Social Consequences of Alcohol Consumption; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godbold, L.C.; Pfau, M. Conferring resistance of peer pressure among adolescents: Using inoculation theory to discourage alcohol use. Commun. Res. 2000, 27, 411–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noar, S.M.; Hall, M.G.; Francis, D.B.; Ribisl, K.M.; Pepper, J.K.; Brewer, N.T. Pictorial cigarette pack warnings: A meta-analysis of experimental studies. Tob. Control 2016, 25, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, J.M. The significance of saturation. Qual. Health Res. 1995, 5, 147–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.-F.; Shannon, S.E. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D.; Tversky, A. Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica 1979, 47, 263–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, P.A.; Fong, G.T. Temporal self-regulation theory: A model for individual health behavior. Health Psychol. Rev. 2007, 1, 6–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, R.W. A protection motivation theory of fear appeals and attitude Change. J. Psychol. 1975, 91, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; Van Stralen, M.M.; West, R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braddock, K.; Dillard, J.P. Meta-analytic evidence for the persuasive effect of narratives on beliefs, attitudes, intentions, and behaviors. Commun. Monogr. 2016, 83, 446–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, D.; Thrasher, J.; Reid, J.L.; Driezen, P.; Boudreau, C.; Santillán, E.A. Perceived effectiveness of pictorial health warnings among Mexican youth and adults: A population-level intervention with potential to reduce tobacco-related inequities. Cancer Causes Control 2012, 23, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Z. The role of narrative pictorial warning labels in communicating alcohol-related cancer risks. Health Commun. 2022, 37, 1345–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, E.; Durkin, S.J.; Cotter, T.; Harper, T.; Wakefield, M.A. Mass media campaigns designed to support new pictorial health warnings on cigarette packets: Evidence of a complementary relationship. Tob. Control 2011, 20, 412–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thrasher, J.F.; Murukutla, N.; Pérez-Hernández, R.; Alday, J.; Arillo-Santillán, E.; Cedillo, C.; Gutierrez, J.P. Linking mass media campaigns to pictorial warning labels on cigarette packages: A cross-sectional study to evaluate effects among Mexican smokers. Tob. Control 2013, 22, e57–e65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weerasinghe, A.; Schoueri-Mychasiw, N.; Vallance, K.; Stockwell, T.; Hammond, D.; McGavock, J.; Greenfield, T.K.; Paradis, C.; Hobin, E. Improving knowledge that alcohol can cause cancer is associated with consumer support for alcohol policies: Findings from a real-world alcohol labelling study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, M.G.; Sheeran, P.; Noar, S.M.; Boynton, M.H.; Ribisl, K.M.; Parada, H., Jr.; Johnson, T.O.; Brewer, N.T. Negative affect, message reactance and perceived risk: How do pictorial cigarette pack warnings change quit intentions? Tob. Control 2018, 27, e136–e142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staub, C.; Siegrist, M. How health warning labels on wine and vodka bottles influence perceived risk, rejection, and acceptance. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, R.E.; Cacioppo, J.T.; Schumann, D. Central and peripheral routes to advertising effectiveness: The moderating role of involvement. J. Consum. Res. 1983, 10, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witte, K.; Allen, M. A meta-analysis of fear appeals: Implications for effective public health campaigns. Health Educ. Behav. 2000, 27, 591–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blank, M.L.; Hoek, J.; Gendall, P. Roll-your-own smokers’ reactions to cessation-efficacy messaging integrated into tobacco packaging design: A sequential mixed-methods study. Tob. Control 2020, 30, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maynard, O.M.; Mc Clernon, F.J.; Oliver, J.A.; Munafò, M.R. Using neuroscience to inform tobacco control policy. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2019, 21, 739–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thrasher, J.F.; Swayampakala, K.; Borland, R.; Nagelhout, G.; Yong, H.-H.; Hammond, D.; Bansal-Travers, M.; Thompson, M.; Hardin, J. Influences of self-efficacy, response efficacy, and reactance on responses to cigarette health warnings: A longitudinal study of adult smokers in Australia and Canada. Health Commun. 2016, 3, 1517–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, H.-H.; Borland, R.; Thrasher, J.F.; Thompson, M.E.; Nagelhout, G.E.; Fong, G.T.; Hammond, D.; Cummings, K.M. Mediational pathways of the impact of cigarette warning labels on quit attempts. Health Psychol. 2014, 33, 1410–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, E.L.; Foxcroft, D.R.; Puljevic, C.; Ferris, J.A.; Winstock, A.R. Global comparisons of responses to alcohol health information labels: A cross sectional study of people who drink alcohol from 29 countries. Addict. Behav. 2022, 131, 107330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participant | Gender | Age | Drinking Profile (AUDIT–C Score) | Highest Educational Attainment | Occupation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | M | 24 | High-risk drinker (7) | High-school qualifications | Student (social work) |

| 2. | F | 18 | Moderate drinker (2) | High-school qualifications | Student (psychology) |

| 3. | F | 19 | High-risk drinker (6) | High-school qualification | Student (social work) |

| 4. | M | 22 | Moderate drinker (3) | University undergraduate | Student (finance) |

| 5. | F | 20 | High-risk drinker (5) | University undergraduate | Student (business)/part-time helpline operator |

| 6. | M | 22 | Moderate drinker (3) | University undergraduate | Student (education)/extracurricular activity leader |

| 7. | M | 19 | High-risk drinker (6) | High-school qualifications | Student (information technology) |

| 8. | F | 22 | Moderate drinker (1) | University undergraduate | Student (physics and chemistry) |

| 9. | F | 25 | High-risk drinker (4) | High-school qualifications | Front desk operator (car rental agency) |

| 10. | M | 19 | Moderate drinker (3) | High-school qualifications | Student (literature) |

| 11. | M | 20 | High-risk drinker (5) | High-school qualifications | Student (business) |

| 12. | F | 19 | Moderate drinker (2) | High-school qualifications | Student (business management) |

| 13. | F | 19 | High-risk drinker (6) | High-school qualifications | Student (opticianry) |

| 14. | F | 25 | Moderate drinker (2) | University undergraduate | Supermarket cashier |

| 15. | M | 20 | High-risk drinker (5) | University undergraduate | Student (sports education)/part-time lifeguard |

| 16. | F | 21 | Moderate drinker (2) | University undergraduate | Student (customer relations/sales) |

| 17. | M | 24 | High-risk drinker (7) | Toolmaker | |

| 18. | F | 23 | High-risk drinker (5) | University undergraduate | Sales rep (civil engineering) |

| 19. | F | 19 | Moderate drinker (2) | High-school qualifications | Student (management support) |

| 20. | M | 20 | High-risk drinker (7) | High-school qualifications | Student (mechanical design and industrialization) |

| 21. | M | 25 | Moderate drinker (3) | Master’s degree | Student (communications) |

| 22. | F | 22 | High-risk drinker (5) | University undergraduate | Social worker |

| 23. | F | 22 | Moderate drinker (2) | University undergraduate | Specialist educator |

| 24. | M | 24 | Moderate drinker (1) | High-school qualifications | Mail carrier in a purchasing department |

| 25. | M | 25 | Moderate drinker (3) | High-school qualifications | Unskilled worker |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dossou, G.T.; Guillou-Landreat, M.; Lemain, L.; Lacoste-Badie, S.; Critchlow, N.; Gallopel-Morvan, K. How Do Young Adult Drinkers React to Varied Alcohol Warning Formats and Contents? An Exploratory Study in France. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6541. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20156541

Dossou GT, Guillou-Landreat M, Lemain L, Lacoste-Badie S, Critchlow N, Gallopel-Morvan K. How Do Young Adult Drinkers React to Varied Alcohol Warning Formats and Contents? An Exploratory Study in France. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(15):6541. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20156541

Chicago/Turabian StyleDossou, Gloria Thomasia, Morgane Guillou-Landreat, Loic Lemain, Sophie Lacoste-Badie, Nathan Critchlow, and Karine Gallopel-Morvan. 2023. "How Do Young Adult Drinkers React to Varied Alcohol Warning Formats and Contents? An Exploratory Study in France" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 15: 6541. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20156541

APA StyleDossou, G. T., Guillou-Landreat, M., Lemain, L., Lacoste-Badie, S., Critchlow, N., & Gallopel-Morvan, K. (2023). How Do Young Adult Drinkers React to Varied Alcohol Warning Formats and Contents? An Exploratory Study in France. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(15), 6541. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20156541