The Relationships between Compulsive Internet Use, Alexithymia, and Dissociation: Gender Differences among Italian Adolescents

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Problematic Internet Use and Adolescence

1.1.1. Problematic Internet Use

1.1.2. Problematic Internet Use: Age and Gender Differences in Adolescence

1.2. Internet Use, Alexithymia, and Dissociation

1.3. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Internet Use. A Set of Items That Assess

2.2.2. Symptoms/Difficulties

2.2.3. Satisfaction with Life

2.2.4. Compulsive Internet Use

2.2.5. Alexithymia

2.2.6. Dissociation

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Results

3.2. Gender and Group Age Differences on TAS-20, A-DES, and CIUS-14 Total Scores

3.3. Gender Differences on TAS-20 and A-DES Subscales

3.4. Correlations between TAS-20, A-DES, and CIUS-14 Dimensions

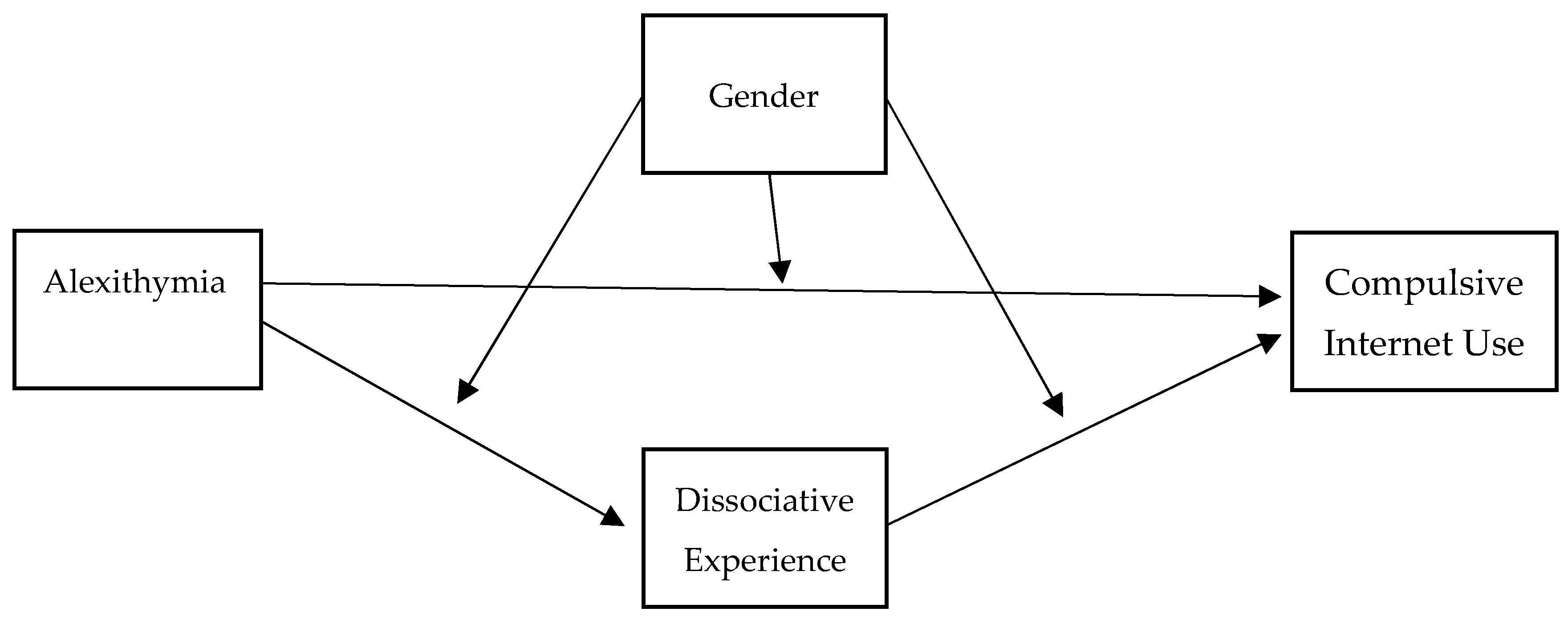

3.5. Moderated Mediation Model with TAS-20, A-DES, and CIUS-14

4. Discussion

4.1. Problematic Internet Use, Alexithymia, and Dissociation Levels

4.2. The Correlations between Internet Use, Alexithymia, and Dissociation

4.3. The Role of Dissociation on the Relation between Alexithymia and Problematic Internet Use

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; Text Rev; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingiardi, V.; e McWilliams, N. Manuale Diagnostico Psicodinamico, 2nd ed.; PDM-2; Raffaello Cortina: Milan, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Meerkerk, G.J.; Van Den Eijnden, R.J.; Vermulst, A.A.; Garretsen, H.F. The Compulsive Internet Use Scale (CIUS): Some Psychometric Properties. CyberPsychology Behav. 2009, 12, 717–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapira, N.A.; Lessig, M.C.; Goldsmith, T.D.; Szabo, S.T.; Lazoritz, M.; Gold, M.S.; Stein, D.J. Problematic internet use: Proposed classification and diagnostic criteria. Depress. Anxiety 2003, 17, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 11th ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://icd.who.int/ (accessed on 1 April 2023).

- Young, K.S. Internet Addiction: The Emergence of a New Clinical Disorder. CyberPsychology Behav. 2009, 1, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrante, L.; Venuleo, C. Problematic Internet Use among adolescents and young adults: A systematic review of scholars’ conceptualisations after the publication of DSM5. Mediterr. J. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 9, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merikangas, K.R.; He, J.-P.; Burstein, M.; Swanson, S.A.; Avenevoli, S.; Cui, L.; Benjet, C.; Georgiades, K.; Swendsen, J. Lifetime Prevalence of Mental Disorders in U.S. Adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication–Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2010, 49, 980–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key Substance use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2021 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP22-07-01-005, NSDUH Series H-57). Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2022. Available online: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2021-nsduh-annual-national-report (accessed on 1 April 2023).

- Solmi, M.; Radua, J.; Olivola, M.; Croce, E.; Soardo, L.; de Pablo, G.S.; Shin, J.I.; Kirkbride, J.B.; Jones, P.; Kim, J.H.; et al. Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: Large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Mol. Psychiatry 2021, 27, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, F.; Rega, V.; Boursier, V. Problematic Internet use and emotional dysregulation among young people: A literature review. Clin. Neuropsychiatry 2021, 18, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craparo, G. Internet addiction, dissociation, and alexithymia. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 30, 1051–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pasquale, C.; Dinaro, C.; Sciacca, F. Relationship of Internet gaming disorder with dissociative experience in Italian university students. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2018, 17, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, A.; Sharma, P. Association of Internet addiction and alexithymia—A scoping review. Addict. Behav. 2018, 81, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topino, E.; Gori, A.; Cacioppo, M. Alexithymia, Dissociation, and Family Functioning in a Sample of Online Gamblers: A Moderated Mediation Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honkalampi, K.; Tolmunen, T.; Hintikka, J.; Rissanen, M.-L.; Kylmä, J.; Laukkanen, E. The prevalence of alexithymia and its relationship with Youth Self-Report problem scales among Finnish adolescents. Compr. Psychiatry 2009, 50, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rieffe, C.; Oosterveld, P.; Terwogt, M.M. An alexithymia questionnaire for children: Factorial and concurrent validation results. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2006, 40, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, F.W. Dissociative disorders in children: Behavioral profiles and problems. Child Abus. Negl. 1993, 17, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolmunen, T.; Maaranen, P.; Hintikka, J.; Kylmä, J.; Rissanen, M.-L.; Honkalampi, K.; Haukijärvi, T.; Laukkanen, E. Dissociation in a General Population of Finnish Adolescents. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2007, 195, 614–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ropovik, I.; Martončik, M.; Babinčák, P.; Baník, G.; Vargová, L.; Adamkovič, M. Risk and protective factors for (internet) gaming disorder: A meta-analysis of pre-COVID studies. Addict. Behav. 2023, 139, 107590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, L.; Schimmenti, A.; Musetti, A.; Boursier, V.; Flayelle, M.; Cataldo, I.; Starcevic, V.; Billieux, J. Deconstructing the components model of addiction: An illustration through “addictive” use of social media. Addict. Behav. 2023, 143, 107694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musetti, A.; Cattivelli, R.; Giacobbi, M.; Zuglian, P.; Ceccarini, M.; Capelli, F.; Pietrabissa, G.; Castelnuovo, G. Internet Addiction Disorder o Internet Related Psychopathology? G. Ital. Di Psicol. 2017, 44, 359–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, P. Internet addiction: Genuine diagnosis or not? Lancet 2000, 355, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, G.R.; Berzonsky, M. (Eds.) Blackwell Handbook of Adolescence; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Musetti, A.; Terrone, G.; Schimmenti, A. An exploratory study on problematic Internet use predictors: Which role for attachment and dissociation? Clin. Neuropsychiatry 2018, 15, 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Schimmenti, A.; Musetti, A.; Costanzo, A.; Terrone, G.; Maganuco, N.R.; Aglieri Rinella, C.; Gervasi, A.M. The unfabulous four: Maladaptive personality functioning, insecure attachment, dissociative experiences, and problematic internet use among young adults. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2021, 19, 447–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morahan-Martin, J.; Schumacher, P. Incidence and correlates of pathological Internet use among college students. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2000, 16, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherer, K. College life on-line: Healthy and unhealthy Internet use. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 1997, 38, 655–665. [Google Scholar]

- Chou, C.; Condron, L.; Belland, J.C. A Review of the Research on Internet Addiction. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2005, 17, 363–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Nicola, M.; Ferri, V.R.; Moccia, L.; Panaccione, I.; Strangio, A.M.; Tedeschi, D.; Grandinetti, P.; Callea, A.; De-Giorgio, F.; Martinotti, G.; et al. Gender Differences and Psychopathological Features Associated with Addictive Behaviors in Adolescents. Front. Psychiatry 2017, 8, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, C.-H.; Yen, J.-Y.; Chen, C.-C.; Chen, S.-H.; Yen, C.-F. Gender Differences and Related Factors Affecting Online Gaming Addiction among Taiwanese Adolescents. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2005, 193, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wang, Z.; Elhai, J.D.; Montag, C. The relationship between adolescent emotion dysregulation and problematic technology use: Systematic review of the empirical literature. J. Behav. Addict. 2022, 11, 290–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratz, K.L.; Roemer, L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation Scale. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2004, 26, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J.; John, O.P. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 348–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preece, D.A.; Mehta, A.; Petrova, K.; Sikka, P.; Bjureberg, J.; Becerra, R.; Gross, J.J. Alexithymia and emotion regulation. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 324, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sifneos, P. The Prevalence of ‘Alexithymic’ Characteristics in Psychosomatic Patients. Psychother. Psychosom. 1973, 22, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagby, R.M.; Parker, J.D.; Taylor, G.J. Twenty-five years with the 20-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale. J. Psychosom. Res. 2020, 131, 109940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrozzino, D.; Porcelli, P. Alexithymia in Gastroenterology and Hepatology: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesio, V.; Goerlich, K.S.; Hosoi, M.; Castelli, L. Editorial: Alexithymia: State of the Art and Controversies. Clinical and Neuroscientific Evidence. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pape, M.; Reichrath, B.; Bottel, L.; Herpertz, S.; Kessler, H.; Dieris-Hirche, J. Alexithymia and internet gaming disorder in the light of depression: A cross-sectional clinical study. Acta Psychol. 2022, 229, 103698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putnam, F.W. Development of dissociative disorders. In Developmental Psycho-Pathology Risk, Disorder, and Adaptation; Cicchetti, D., Cohen, D.J., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1995; Volume 2, pp. 581–608. [Google Scholar]

- Elzinga, B.M.; Bermond, B.; van Dyck, R. The Relationship between Dissociative Proneness and Alexithymia. Psychother. Psychosom. 2002, 71, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grabe, H.-J.; Rainermann, S.; Spitzer, C.; Gänsicke, M.; Freyberger, H. The Relationship between Dimensions of Alexithymia and Dissociation. Psychother. Psychosom. 2000, 69, 128–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modestin, J.; Lötscher, K.; Erni, T. Dissociative experiences and their correlates in young non-patients. Psychol. Psychother. Theory, Res. Pr. 2002, 75, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayar, K.; Kose, S.; Grabe, H.J.; Topbas, M. Alexithymia and dissociative tendencies in an adolescent sample from Eastern Turkey. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2005, 59, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolmunen, T.; Honkalampi, K.; Hintikka, J.; Rissanen, M.-L.; Maaranen, P.; Kylmä, J.; Laukkanen, E. Adolescent dissociation and alexithymia are distinctive but overlapping phenomena. Psychiatry Res. 2010, 176, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guertler, D.; Rumpf, H.-J.; Bischof, A.; Kastirke, N.; Petersen, K.U.; John, U.; Meyer, C. Assessment of Problematic Internet Use by the Compulsive Internet Use Scale and the Internet Addiction Test: A Sample of Problematic and Pathological Gamblers. Eur. Addict. Res. 2014, 20, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Fernandez, O.; Griffiths, M.D.; Kuss, D.J.; Dawes, C.; Pontes, H.M.; Justice, L.; Rumpf, H.-J.; Bischof, A.; Gässler, A.-K.; Suryani, E.; et al. Cross-Cultural Validation of the Compulsive Internet Use Scale in Four Forms and Eight Languages. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2019, 22, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressi, C.; Taylor, G.; Parker, J.; Bressi, S.; Brambilla, V.; Aguglia, E.; Allegranti, I.; Bongiorno, A.; Giberti, F.; Bucca, M.; et al. Cross validation of the factor structure of the 20-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale: An Italian multicenter study. J. Psychosom. Res. 1996, 41, 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, J.G.; Putnam, F.W.; Carlson, E.B.; Libero, D.Z.; Smith, S.R. Development and Validation of a Measure of Adolescent Dissociation: The Adolescent Dissociative Experiences Scale. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1997, 185, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pasquale, C.; Sciacca, F.; Hichy, Z. Validation of the Italian version of the dissociative experience scale for ado-lescents and young adults. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2016, 15, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schimmenti, A. Psychometric Properties of the Adolescent Dissociative Experiences Scale (A-DES) in a Sample of Italian Adolescents. J. Trauma Dissociation 2016, 17, 244–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, D.; Mallery, P. IBM SPSS Statistics 27 Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference; Routledge: Milton Park, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germani, A.; DelVecchio, E.; Elisa, D.; Lis, A.; Mazzeschi, C. Meaning in Life as Mediator of Family Allocentrism and Depressive Symptoms Among Chinese and Italian Early Adolescents. Youth Soc. 2021, 53, 252–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. An Index and Test of Linear Moderated Mediation. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2015, 50, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaafar, N.R.N.; Bahar, N.; Ibrahim, N.; Ismail, W.S.W.; Baharudin, A. Excessive internet use in young women. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2017, 30, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boursier, V.; Gioia, F.; Griffiths, M.D. Objectified Body Consciousness, Body Image Control in Photos, and Problematic Social Networking: The Role of Appearance Control Beliefs. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beutel, M.E.; Brähler, E.; Glaesmer, H.; Kuss, D.J.; Wölfling, K.; Müller, K.W.; Dempsey, A.G.; Sulkowski, M.L.; Dempsey, J.; Storch, E.A.; et al. Regular and Problematic Leisure-Time Internet Use in the Community: Results from a German Population-Based Survey. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2011, 14, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Early (n = 121) | Middle (n = 238) | Late (n = 235) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Test | |||

| N | (n = 54) | (n = 67) | (n = 106) | (n = 132) | (n = 123) | (n = 112) | n.s. | ||

| M ± SD | M ± SD | M ± SD | M ± SD | M ± SD | M ± SD | G | G. A. | Int. | |

| Listening to music | 3.31 ± 0.82 | 2.84 ± 0.88 | 3.29 ± 0.75 | 3.01 ± 0.85 | 3.17 ± 0.82 | 3.37 ± 0.67 | * | n.s. | * |

| 3.05 ± 0.88 | 3.14± 0.82 | 3.26 ± 0.75 | |||||||

| Watching videos/series | 3.02 ± 0.81 | 3.00 ± 0.83 | 2.92 ± 0.81 | 2.94 ± 0.89 | 3.00 ± 0.85 | 3.25 ± 0.81 | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| 3.01 ± 0.82 | 2.93 ±0.85 | 3.12 ± 0.84 | |||||||

| Viewing images, photos, stories | 2.96 ± 0.84 | 2.51 ± 0.99 | 3.12 ± 0.72 | 2.65 ± 0.83 | 3.16 ± 0.74 | 3.01 ± 0.75 | * | * | * |

| 2.71 ± 0.95 | 2.89 ± 0.82 | 3.01 ± 0.75 | |||||||

| Gaming | 1.89 ± 0.88 | 2.78 ± 0.98 | 1.91 ± 0.76 | 2.48 ± 0.88 | 1.80 ± 0.89 | 2.47 ± 1.00 | ** | n.s. | n.s. |

| 2.38 ± 1.03 | 2.22 ± 0.87 | 2.12 ± 1.00 | |||||||

| Searching for information | 2.91 ± 0.68 | 2.64 ± 0.88 | 2.94 ± 0.55 | 2.97 ± 0.75 | 3.19 ± 0.70 | 3.00 ± 0.63 | * | * | n.s. |

| 2.76 ± 0.81 | 2.96 ± 0.67 | 3.10 ± 0.67 | |||||||

| Studying | 2.81 ± 0.73 | 2.67 ± 0.86 | 2.98 ± 0.70 | 2.73 ± 0.76 | 3.17 ± 0.74 | 2.72 ± 0.74 | * | n.s. | n.s. |

| 2.74 ± 0.80 | 2.84 ± 0.74 | 2.96 ± 0.77 | |||||||

| Chatting with friends/acquaintances | 3.43 ± 0.74 | 3.03 ± 0.87 | 3.57 ± 0.55 | 3.29 ± 0.78 | 3.58 ± 0.56 | 3.48 ± 0.57 | * | * | n.s. |

| 3.21 ± 0.83 | 3.42 ± 0.70 | 3.54 ± 0.56 | |||||||

| Sending/receiving email | 1.81 ± 0.80 | 1.55 ± 0.63 | 1.74 ± 0.65 | 1.69 ± 0.68 | 2.24 ± 0.76 | 1.89 ± 0.71 | * | ** | n.s. |

| 1.67 ± 0.72 | 1.71 ± 0.66 | 2.07 ± 0.76 | |||||||

| Navigating without a destination | 2.06 ± 1.02 | 1.81 ± 0.89 | 2.37 ± 0.97 | 1.91 ± 0.95 | 2.41 ± 0.95 | 1.94 ± 0.88 | * | n.s. | n.s. |

| 1.93 ± 0.95 | 2.11 ± 0.98 | 2.18 ± 0.94 | |||||||

| Shopping | 1.91 ± 0.73 | 1.90 ± 0.78 | 2.24 ± 0.83 | 1.87 ± 0.82 | 2.41 ± 0.87 | 2.04 ± 0.78 | * | * | n.s. |

| 1.90 ± 0.76 | 2.03 ± 0.85 | 2.23 ± 0.85 | |||||||

| Making new friends or dating | 1.78 ± 0.86 | 1.70 ± 0.80 | 1.62 ± 0.83 | 1.60 ± 0.86 | 1.64 ± 0.83 | 1.75 ± 0.81 | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| 1.74 ± 0.82 | 1.61 ± 0.85 | 1.69 ± 0.82 | |||||||

| Time spent on the internet | 2.78 ± 0.46 | 2.54 ± 0.78 | 2.80 ± 0.56 | 2.70 ± 0.52 | 2.75 ± 0.57 | 2.82 ± 0.41 | n.s. | n.s. | * |

| 2.64 ± 0.67 | 2.74 ± 0.54 | 2.78 ± 0.50 | |||||||

| Symptoms/Difficulties | 2.25 ± 0.69 | 1.53 ± 0.43 | 2.32 ± 0.68 | 1.75 ± 0.59 | 2.35 ± 0.61 | 1.91 ± 0.59 | *** | * | n.s. |

| 1.85 ± 0.66 | 2.01 ± 0.69 | 2.14 ± 0.64 | |||||||

| Satisfaction with Life | 2.91 ± 0.63 | 2.98 ± 0.57 | 2.78 ± 0.57 | 2.89 ± 0.61 | 2.73 ± 0.52 | 2.79 ± 0.58 | n.s. | * | n.s. |

| 2.95 ± 0.60 | 2.84 ± 0.59 | 2.76 ± 0.55 | |||||||

| Females (n = 283) | Males (n = 311) | F | p | ŋp2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||||

| TAS-20 TS | 58.26 | 0.72 | 51.54 | 0.67 | 46.91 | 0.000 | 0.074 |

| A-DES TS | 2.90 | 0.12 | 2.66 | 0.11 | 2.17 | 0.141 | 0.004 |

| CIUS-14 | 22.58 | 0.69 | 17.51 | 0.64 | 28.93 | 0.000 | 0.047 |

| Early (n = 121) | Middle (n = 238) | Late (n = 235) | F | p | ŋp2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | ||||

| TAS-20 TS | 55.56 | 1.04 | 54.87 | 0.74 | 54.26 | 0.74 | 0.54 | 0.584 | 0.002 |

| A-DES TS | 2.97 | 0.17 | 2.69 | 0.13 | 2.69 | 0.13 | 0.97 | 0.381 | 0.003 |

| CIUS-14 | 20.42 | 0.99 | 18.58 | 0.71 | 21.12 | 0.71 | 3.31 | 0.037 | 0.011 |

| Females (n = 283) | Males (n = 311) | F | p | ŋp2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||||

| DIF | 19.89 | 0.42 | 15.82 | 0.40 | 48.10 | 0.000 | 0.075 |

| DDF | 17.28 | 0.26 | 13.95 | 0.25 | 81.63 | 0.000 | 0.121 |

| EOT | 20.73 | 0.25 | 21.69 | 0.24 | 7.21 | 0.007 | 0.012 |

| DA | 2.73 | 0.12 | 2.55 | 0.12 | 1.01 | 0.317 | 0.002 |

| AbII | 2.86 | 0.12 | 2.82 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.797 | 0.001 |

| DD | 2.84 | 0.12 | 2.48 | 0.12 | 4.66 | 0.031 | 0.008 |

| PI | 3.12 | 0.13 | 2.86 | 0.13 | 2.03 | 0.155 | 0.003 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. DIF | - | 0.67 * | −0.01 | 0.87 * | 0.34 * | 0.34 * | 0.48 * | 0.40 * | 0.45 * | 0.38 * |

| 2. DDF | 0.70 * | - | 0.02 | 0.81 * | 0.16 * | 0.08 | 0.23 * | 0.15 * | 0.19 * | 0.24 * |

| 3. EOT | −0.10 | −0.13 * | - | 0.39 * | 0.19 * | 0.21 * | 0.11 | 0.13 * | 0.16 * | 0.13 * |

| 4. TAS TS | 0.90 * | 0.80 * | 0.25 * | - | 0.34 * | 0.32 * | 0.43 * | 0.35 * | 0.41 * | 0.38 * |

| 5. DA | 0.38 * | 0.22 * | 0.23 * | 0.42 * | - | 0.78 * | 0.78 * | 0.77 * | 0.91 * | 0.30 * |

| 6. AbII | 0.35 * | 0.20 * | 0.19 * | 0.38 * | 0.86 * | - | 0.76 * | 0.74 * | 0.88 * | 0.32 * |

| 7. DD | 0.44 * | 0.26 * | 0.16 * | 0.45 * | 0.88 * | 0.83 * | - | 0.82 * | 0.95 * | 0.33 * |

| 8. PI | 0.44 * | 0.25 * | 0.12 * | 0.43 * | 0.83 * | 0.78 * | 0.84 * | - | 0.90 * | 0.33 * |

| 9. A-DES TS | 0.43 * | 0.25 * | 0.19 * | 0.45 * | 0.95 * | 0.92 * | 0.97 * | 0.91 * | - | 0.35 * |

| 10. CIUS-14 | 0.44 * | 0.35 * | 0.02 | 0.44 * | 0.23 * | 0.26 * | 0.26 * | 0.22 * | 0.26 * | - |

| Paths | Direct Effects | Indirect Effects | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | se | t | p | b | CI (95%) | |

| Total sample (N = 594) TAS-20 TS →A-DES TS Gender →A-DES TS TAS-20 TS x Gender →A-DES TS A-DES TS →CIUS-14 Gender →CIUS-14 A-DES TS x Gender →CIUS-14 TAS-20 TS →CIUS-14 TAS-20 TS x Gender →CIUS-14 | 2.232 7.099 0.597 0.029 −2.921 −0.035 0.332 0.132 | 0.190 4.472 0.380 0.007 0.845 0.015 0.040 0.079 | 11.69 1.59 1.57 3.83 −3.46 −2.28 8.30 1.66 | <0.001 0.112 0.117 <0.001 <0.001 0.023 <0.001 0.096 | ||

| Females (n = 283) A-DES TS →CIUS-14 TAS-20 TS →CIUS-14 | 0.048 0.262 | 0.011 0.053 | 4.23 4.89 | <0.001 <0.001 | 0.093 | 0.093, 0.158 |

| Males (n = 311) A-DES TS →CIUS-14 TAS-20 TS →CIUS-14 | 0.012 0.395 | 0.010 0.058 | 1.21 6.72 | 0.224 <0.001 | 0.032 | −0.024, 0.090 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Germani, A.; Lopez, A.; Martini, E.; Cicchella, S.; De Fortuna, A.M.; Dragone, M.; Pizzini, B.; Troisi, G.; De Luca Picione, R. The Relationships between Compulsive Internet Use, Alexithymia, and Dissociation: Gender Differences among Italian Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6431. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20146431

Germani A, Lopez A, Martini E, Cicchella S, De Fortuna AM, Dragone M, Pizzini B, Troisi G, De Luca Picione R. The Relationships between Compulsive Internet Use, Alexithymia, and Dissociation: Gender Differences among Italian Adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(14):6431. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20146431

Chicago/Turabian StyleGermani, Alessandro, Antonella Lopez, Elvira Martini, Sara Cicchella, Angelo Maria De Fortuna, Mirella Dragone, Barbara Pizzini, Gina Troisi, and Raffaele De Luca Picione. 2023. "The Relationships between Compulsive Internet Use, Alexithymia, and Dissociation: Gender Differences among Italian Adolescents" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 14: 6431. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20146431

APA StyleGermani, A., Lopez, A., Martini, E., Cicchella, S., De Fortuna, A. M., Dragone, M., Pizzini, B., Troisi, G., & De Luca Picione, R. (2023). The Relationships between Compulsive Internet Use, Alexithymia, and Dissociation: Gender Differences among Italian Adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(14), 6431. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20146431