Completion of the Continuum of Maternity Care in the Emerging Regions of Ethiopia: Analysis of the 2019 Demographic and Health Survey

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

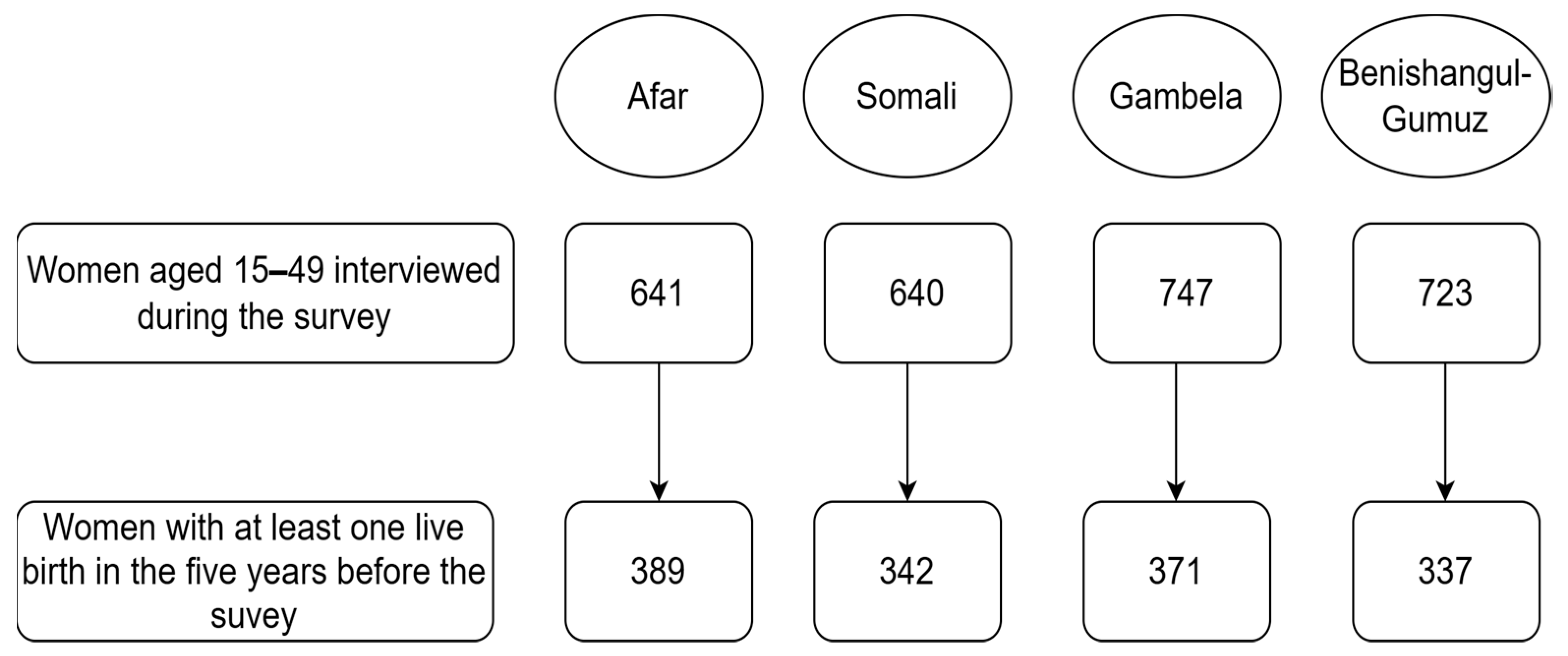

2.2. Population

2.3. Study Variables

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Participants

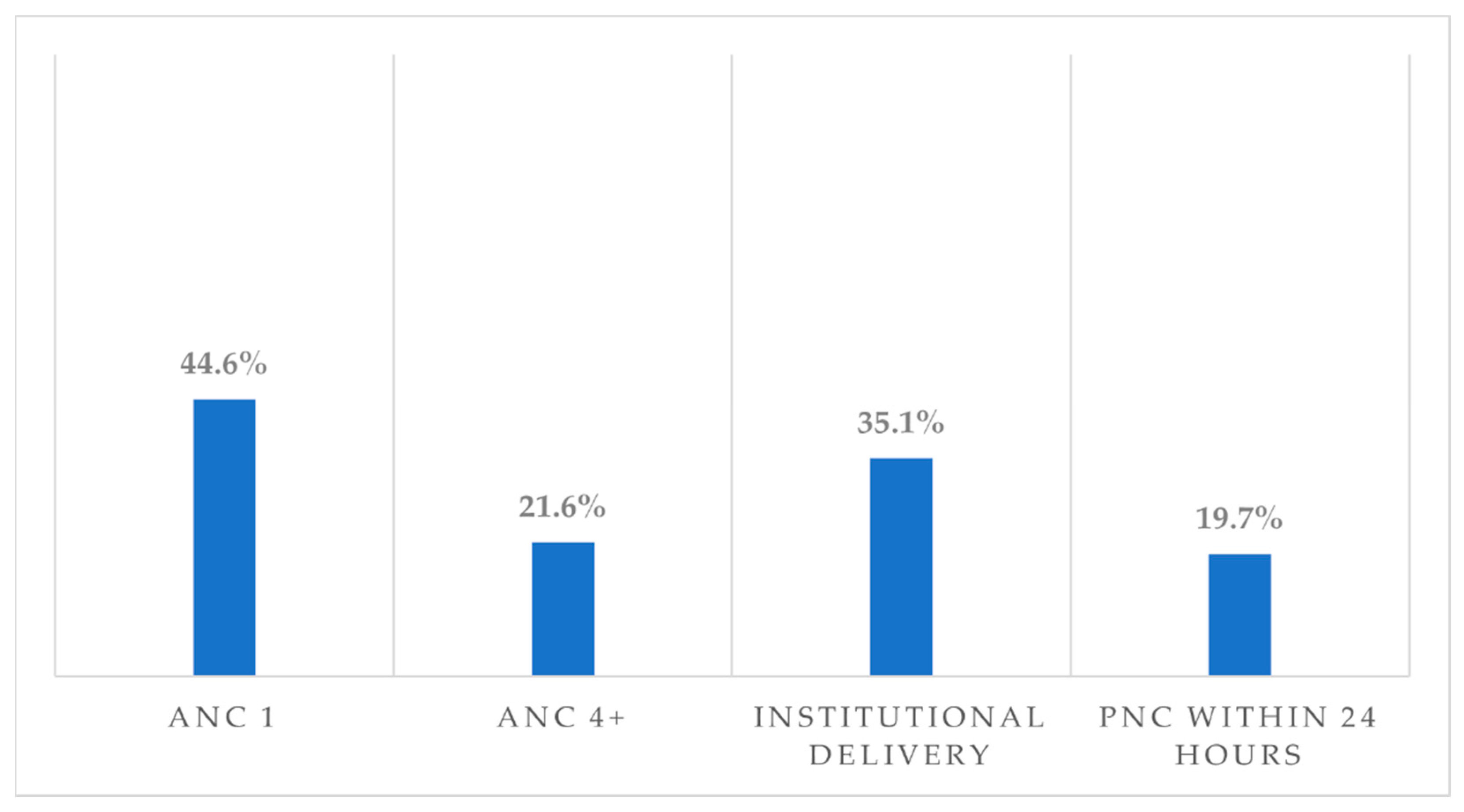

3.2. Maternal Healthcare Utilisation

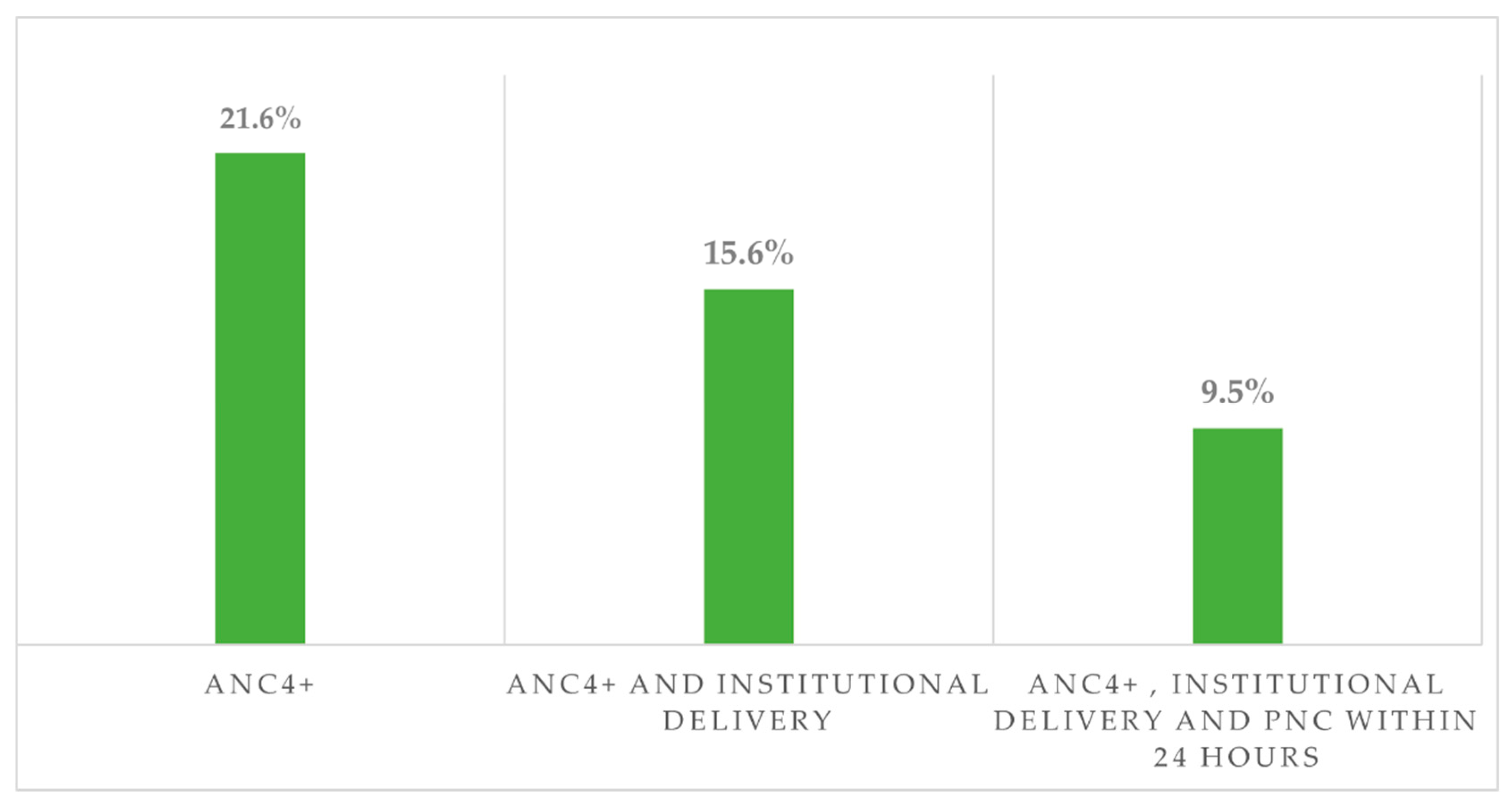

3.3. Continuum of Maternity Care

3.4. Factors Associated with Maternal Health Care Utilisation

3.4.1. ANC4+

3.4.2. Institutional Delivery

3.4.3. PNC within 24 h

3.5. Factors Associated with Completion of the Continuum of Maternity Care

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO; UNICEF; UNFPA; World Bank Group and UNDESA/Population Division. Trends in Maternal Mortality 2000 to 2020: Estimates; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Say, L.; Chou, D.; Gemmill, A.; Tunçalp, Ö.; Moller, A.B.; Daniels, J.; Gülmezoglu, A.M.; Temmerman, M.; Alkema, L. Global causes of maternal death: A WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob. Healh 2014, 2, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO; UNFPA. Ending Preventable Maternal Mortality (EPMM): A Renewed Focus for Improving Maternal and Newborn Health and Welbeing. 2021. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/350834 (accessed on 5 June 2023).

- Worku, M.; Zewudie, F.; Banbeta, A. Spatial Pattern and Determinants of Maternal Death in Ethiopia: Analysis Based on 2016 EDHS Data. 2020. Available online: https://repository.ju.edu.et/bitstream/handle/123456789/5098/muletafinal.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 4 November 2022).

- Jabessa, S.; Jabessa, D. Bayesian multilevel model on maternal mortality in Ethiopia. J. Big Data 2021, 8, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geleto, A.; Chojenta, C.; Taddele, T.; Loxton, D. Magnitude and determinants of obstetric case fatality rate among women with the direct causes of maternal deaths in Ethiopia: A national cross sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations in Ethiopia. Joint Programme in the Developing Regional States of Ethiopia. Afar, Benishangul Gumuz, Gambella & Somali Regional States; United Nations in Ethiopia: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Ethiopia Ministry of Affairs. Emerging Regions Development Programme (ERDP); Government of Ethiopia Ministry of Affairs: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2007; p. 30. [Google Scholar]

- Kibret, G.D.; Demant, D.; Hayen, A. Geographical accessibility of emergency neonatal care services in Ethiopia: Analysis using the 2016 Ethiopian Emergency Obstetric and Neonatal Care Survey. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e058648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkema, L.; Chou, D.; Hogan, D.; Zhang, S.; Moller, A.B.; Gemmill, A.; Fat, D.M.; Boerma, T.; Temmerman, M.; Mathers, C.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Levels and Trends in Maternal Mortality Between 1990 and 2015, with Scenario-based Projections to 2030: A Systematic Analysis by the UN Maternal Mortality Estimation Inter-Agency Group. Lancet 2016, 387, 462–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Han, X.; You, L.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, L.; Liu, Y. Maternal health services utilization and maternal mortality in China: A longitudinal study from 2009 to 2016. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassi, Z.S.; Salam, R.A.; Das, J.K.; Bhutta, Z.A. Essential interventions for maternal, newborn and child health: Background and methodology. Reprod. Health 2014, 11, S1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldenberg, R.L.; McClure, E.M. Maternal, fetal and neonatal mortality: Lessons learned from historical changes in high income countries and their potential application to low-income countries. Matern. Health Neonatol. Perinatol. 2015, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerber, K.J.; de Graft-Johnson, J.E.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Okong, P.; Starrs, A.; Lawn, J.E. Continuum of care for maternal, newborn, and child health: From slogan to service delivery. Lancet 2007, 370, 1358–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, K.; Ansah, E.K.; Okawa, S.; Enuameh, Y.; Yasuoka, J.; Nanishi, K.; Shibanuma, A.; Gyapong, M.; Owusu-Agyei, S.; Oduro, A.R.; et al. Effective linkages of continuum of care for improving neonatal, perinatal, and maternal mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0139288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelka, M.A.; Yalew, A.W.; Debelew, G.T. The effects of completion of continuum of care in maternal health services on adverse birth outcomes in Northwestern Ethiopia: A prospective follow-up study. Reprod. Health 2022, 19, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Homer, C.S.E. Models of maternity care: Evidence for midwifery continuity of care. Med. J. Aust. 2016, 205, 370–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serawit, M.J.; Legesse, T.W.; Gebi, A. Predictors of institutional delivery service utilization, among women of reproductive age group in Dima District, Agnua zone, Gambella, Ethiopia. Med. Pract. Rev. 2018, 9, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haile, G.T.; Nhial, B.C. Antenatal Care Attendance and Associated Factors in Gambella Region: A Community Based Cross-Sectional Study. J. Posit. Sch. Psychol. 2022, 6, 901–907. [Google Scholar]

- Amentie, M. Individual and Community-level determinants of maternal health services utilization in Northwest Ethiopia: Multilevel Analysis. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e061293. [Google Scholar]

- Kedir Roble, A.; Mohammed Ibrahim, A.; Omar Osman, M.; Tadesse Wedajo, G.; Usman Absiye, A.; Olad Hudle, R. Postnatal Care Service Utilization and Associated Factor among Reproductive Age Women Who Live in Dolo Addo District, Somali Region, Southeast Ethiopia. Eur. J. Prev. Med. 2020, 8, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zepro, N.B.; Ahmed, A.T. Determinants of institutional delivery service utilization among pastorals of Liben Zone, Somali Regional State, Ethiopia, 2015. Int. J. Womens Health 2016, 8, 705–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmi, E.O.H.; Hussein, N.A.; Hassan, A.M.; Ismail, A.M.; Abdulrahman, A.A.; Muse, A.M. Antenatal Care: Utilization Rate and Barriers in Bosaso-Somalia, 2019. Eur. J. Prev. Med. 2021, 9, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biza, N.; Mohammed, H. Pastoralism and antenatal care service utilization in Dubti District, Afar, Ethiopia, 2015: A cross-sectional study. Pastoralism 2016, 6, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadik, W.; Bayray, A.; Debie, A.; Gebremedhin, T. Factors associated with institutional delivery practice among women in pastoral community of Dubti district, Afar region, Northeast Ethiopia: A community-based cross-sectional study. Reprod. Health. 2019, 16, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liben, M.L.; Wuhen, A.G.; Zepro, N.B.; Reddy, P.S. Postnatal care service utilization and associated factors among pastoralist communities in Afar national regional state, northeastern Ethiopia 2016. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2018, 7, 72–75. [Google Scholar]

- Tiruaynet, K.; Muchie, K.F. Determinants of utilization of antenatal care services in Benishangul Gumuz Region, Western Ethiopia: A study based on demographic and health survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019, 19, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eshete, T.; Legesse, M.; Ayana, M. Utilization of institutional delivery and associated factors among mothers in rural community of Pawe Woreda northwest Ethiopia, 2018. BMC Res Notes 2019, 12, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ethiopian Public Health Institute (EPHI); ICF. Ethiopia Mini Demographic and Health Survey 2019: Final Report. 2021, pp. 1–207. Available online: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR363/FR363.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2023).

- Asratie, M.H.; Muche, A.A.; Geremew, A.B. Completion of maternity continuum of care among women in the post-partum period: Magnitude and associated factors in the northwest, Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emiru, A.A.; Alene, G.D.; Debelew, G.T. Women’s retention on the continuum of maternal care pathway in west Gojjam zone, Ethiopia: Multilevel analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atnafu, A.; Kebede, A.; Misganaw, B.; Teshome, D.F.; Biks, G.A.; Demissie, G.D.; Wolde, H.F.; Gelaye, K.A.; Yitayal, M.; Ayele, T.A.; et al. Determinants of the continuum of maternal healthcare services in northwest Ethiopia: Findings from the primary health care project. J. Pregnancy 2020, 2020, 4318197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsega, D.; Admas, M.; Talie, A.; Tsega, T.B.; Birhanu, M.Y.; Alemu, S.; Mengist, B. Maternity Continuum Care Completion and Its Associated Factors in Northwest Ethiopia. J. Pregnancy 2022, 2022, 1309881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadi, T.L.; Medhin, G.; Kasaye, H.K.; Kassie, G.M.; Jebena, M.G.; Gobezie, W.A.; Alemayehu, Y.K.; Teklu, A.M. Continuum of maternity care among rural women in Ethiopia: Does place and frequency of antenatal care visit matter. Reprod. Health 2021, 18, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailemariam, T.; Atnafu, A.; Gezie, L.D.; Tilahun, B. Why maternal continuum of care remains low in Northwest Ethiopia? A multilevel logistic regression analysis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0274729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shitie, A.; Assefa, N.; Dhressa, M.; Dilnessa, T. Completion and Factors Associated with Maternity Continuum of Care among Mothers Who Gave Birth in the Last One Year in Enemay District, Northwest Ethiopia. J. Pregnancy 2020, 2020, 7019676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, R.; Sultan, M.; Abose, S.; Assefa, B.; Nuramo, A.; Alemu, A.; Demelash, M.; Eanga, S.; Mosa, H. Levels and associated factors of the maternal healthcare continuum in Hadiya zone, Southern Ethiopia: A multilevel analysis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0275752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addisu, D.; Mekie, M.; Melkie, A.; Abie, H.; Dagnew, E.; Bezie, M.; Degu, A.; Biru, S.; Chanie, E.S. Continuum of maternal healthcare services utilization and its associated factors in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Women’s Health 2022, 18, 1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiruneh, G.T.; Demissie, M.; Worku, A.; Berhane, Y. Predictors of maternal and newborn health service utilization across the continuum of care in Ethiopia: Amultilevel analysis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sertsewold, S.G.; Debie, A.; Geberu, D.M. Continuum of maternal healthcare services utilisation and associated factors among women who gave birth in Siyadebirena Wayu district, Ethiopia: Community-based cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e051148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alem, A.Z.; Shitu, K.; Alamneh, T.S. Coverage and factors associated with completion of continuum of care for maternal health in sub-Saharan Africa: A multicountry analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akinyemi, J.O.; Afolabi, R.F.; Awolude, O.A. Patterns and determinants of dropout from maternity care continuum in Nigeria. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016, 16, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tizazu, M.A.; Sharew, N.T.; Mamo, T.; Zeru, A.B.; Asefa, E.Y.; Amare, N.S. Completing the continuum of maternity care and associated factors in debre berhan town, amhara, Ethiopia, 2020. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2021, 14, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherie, N.; Abdulkerim, M.; Abegaz, Z.; Walle Baze, G. Maternity continuum of care and its determinants among mothers who gave birth in Legambo district, South Wollo, northeast Ethiopia. Health Sci. Rep. 2021, 4, e409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ethiopia Ministry of Health (MOH). National Antenatal Care Guideline: Ensuring Postive Pregnancy Experiance [Internet]. 2022. Available online: https://icapdatadissemination.wikischolars.columbia.edu/file/view/TRAC+report_Rwanda+National+ART+Evaluation_Final_18Jan08.doc/355073978/TRAC+report_Rwanda+National+ART+Evaluation_Final_18Jan08.doc (accessed on 5 June 2023).

- World Health Organization. WHO Recommendations on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health. Management Protocol on Selected Obstetrics Topics; Government of Ethiopia Ministry of Health: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WHO Recommendations on Postnatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience. 2022. Available online: www.mcsprogram.org (accessed on 5 June 2023).

- Ethiopia Ministry of Health (MOH). Obstetrics Management Protocol for Health Centers; Government of Ethiopia Ministry of Health: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Basha, G.W. Factors Affecting the Utilization of a Minimum of Four Antenatal Care Services in Ethiopia. Obstet. Gynecol. Int. 2019, 2019, 5036783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemayehu, M.; Gebrehiwot, T.G.; Medhanyie, A.A.; Desta, A.; Alemu, T.; Abrha, A.; Godefy, H. Utilization and factors associated with antenatal, delivery and postnatal Care Services in Tigray Region, Ethiopia: A community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fikre, A.A.; Demissie, M. Prevalence of institutional delivery and associated factors in Dodota Woreda (district), Oromia regional state, Ethiopia. Reprod. Health. 2012, 9, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ketemaw, A.; Tareke, M.; Dellie, E.; Sitotaw, G.; Deressa, Y.; Tadesse, G.; Debalkie, D.; Ewunetu, M.; Alemu, Y.; Debebe, D. Factors associated with institutional delivery in Ethiopia: A cross sectional study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shallo, S.A.; Daba, D.B.; Abubekar, A. Demand–supply-side barriers affecting maternal health service utilization among rural women of West Shoa Zone, Oromia, Ethiopia: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0274018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berhe, A.; Bayray, A.; Berhe, Y.; Teklu, A.; Desta, A.; Araya, T.; Zielinski, R.; Roosevelt, L. Determinants of postnatal care utilization in Tigray, Northern Ethiopia: A community based cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0221161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsegaye, B.; Amare, B.; Reda, M. Prevalence and factors associated with immediate postnatal care utilization in ethiopia: Analysis of Ethiopian demographic health survey 2016. Int. J. Womens Health 2021, 13, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kifle, D.; Azale, T.; Gelaw, Y.A.; Melsew, Y.A. Maternal health care service seeking behaviors and associated factors among women in rural Haramaya District, Eastern Ethiopia: A triangulated community-based cross-sectional study. Reprod. Health 2017, 14, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asrat, A.A.; Mengistu, A. Factors associated with utilization of institutional delivery care and postnatal care services in Ethiopia. J. Public Health Epidemiol. 2018, 10, 108–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solanke, B.L. Do the determinants of institutional delivery among childbearing women differ by health insurance enrolment? Findings from a population-based study in Nigeria. Int. J. Health Plann. Manag. 2021, 36, 668–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.P.; Singh, T.; Chaurasia, A.R. Statistical study for utilization of institutional delivery: An evidences from NFHS data. Int. J. Stat. Appl. Math. 2021, 6, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezmur, M.; Navaneetham, K.; Letamo, G.; Bariagaber, H. Socioeconomic inequalities in the uptake of maternal healthcare services in Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuneh, A.D.; Medhanyie, A.A.; Bezabih, A.M.; Persson, L.Å.; Schellenberg, J.; Okwaraji, Y.B. Wealth-based equity in maternal, neonatal, and child health services utilization: A cross-sectional study from Ethiopia. Int. J. Equity Health 2019, 18, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishanga, D.R.; Drake, M.; Kim, Y.M.; Mwanamsangu, A.H.; Makuwani, A.M.; Zoungrana, J.; Lemwayi, R.; Rijken, M.J.; Stekelenburg, J. Factors associated with institutional delivery: Findings from a cross-sectional study in Mara and Kagera regions in Tanzania. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0209672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, P.L.; Pandey, S. Factors influencing institutional delivery and the role of accredited social health activist (ASHA): A secondary analysis of India human development survey 2012. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neupane, S.; Doku, D. Utilization of postnatal care among nepalese women. Matern. Child Health J. 2013, 17, 1922–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debie, A.; Tesema, G.A. Time to early initiation of postnatal care service utilization and its predictors among women who gave births in the last 2 years in Ethiopia: A shared frailty model. Arch. Public Health 2021, 79, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usta, I.M.; Nassar, A.H. Advanced maternal age. Part I: Obstetric complications. Am. J. Perinatol. 2008, 25, 521–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavazos-Rehg, P.A.; Krauss, M.J.; Spitznagel, E.L.; Bommarito, K.; Madden, T.; Olsen, M.A.; Subramaniam, H.; Peipert, J.F.; Bierut, L.J. Maternal Age and Risk of Labor and Delivery Complications. Matern. Child Health J. 2015, 19, 1202–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limenih, M.A.; Endale, Z.M.; Dachew, B.A. Postnatal Care Service Utilization and Associated Factors among Women Who Gave Birth in the Last 12 Months prior to the Study in Debre Markos Town, Northwestern Ethiopia: A Community-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Reprod. Med. 2016, 2016, 7095352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiruneh, G.T.; Worku, A.; Berhane, Y.; Betemariam, W.; Demissie, M. Determinants of postnatal care utilization in Ethiopia: A multilevel analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandall, J.; Tribe, R.M.; Avery, L.; Mola, G.; Visser, G.H.; Homer, C.S.; Gibbons, D.; Kelly, N.M.; Kennedy, H.P.; Kidanto, H.; et al. Short-term and long-term effects of caesarean section on the health of women and children. Lancet 2018, 392, 1349–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Categories | Completion of the Continuum of Maternity Care | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||||

| n | % * | n | % * | ||

| Maternal age at the time of delivery (years) | <20 | 39 | 2.0 | 211 | 11.5 |

| 20–34 | 134 | 6.5 | 862 | 65.0 | |

| 35–49 | 25 | 1.0 | 160 | 14.0 | |

| Residence | Rural | 132 | 4.1 | 1043 | 64.3 |

| Urban | 66 | 5.5 | 190 | 26.2 | |

| Region | Afar | 43 | 2.0 | 344 | 13.2 |

| Somali | 8 | 1.9 | 333 | 63.3 | |

| Benishangul-Gumuz | 103 | 4.6 | 266 | 9.4 | |

| Gambela | 44 | 1.0 | 290 | 4.6 | |

| Marital status | Not married/not living with partner | 23 | 1.0 | 102 | 5.7 |

| Married/living with partner | 175 | 8.5 | 1131 | 84.8 | |

| Religion | Orthodox | 35 | 1.9 | 146 | 4.8 |

| Catholic | 0 | 0.0 | 17 | 0.2 | |

| Protestant | 38 | 1.1 | 222 | 4.5 | |

| Muslim | 124 | 6.5 | 826 | 80.6 | |

| Other | 1 | 0.0 ** | 22 | 0.5 | |

| Highest level of maternal education | No education | 77 | 3.7 | 777 | 69.0 |

| Primary | 83 | 3.5 | 336 | 16.5 | |

| Secondary and higher | 38 | 2.3 | 120 | 5.0 | |

| Sex of the head of the household | Male | 140 | 7.2 | 851 | 55.0 |

| Female | 58 | 2.3 | 382 | 35.5 | |

| Household wealth index | Poorest | 46 | 2.4 | 728 | 60.6 |

| Poorer | 32 | 1.1 | 179 | 9.0 | |

| Middle | 34 | 1.0 | 121 | 5.9 | |

| Richer | 33 | 1.1 | 108 | 6.4 | |

| Richest | 53 | 3.8 | 97 | 8.6 | |

| Number of children | 1–2 | 90 | 4.3 | 409 | 23.7 |

| 3–4 | 36 | 2.2 | 337 | 23.2 | |

| >=5 | 72 | 3.0 | 487 | 43.6 | |

| Mode of delivery | Vaginal | 179 | 8.5 | 1213 | 89.3 |

| Caesarean section | 19 | 1.0 | 20 | 1.2 | |

| Variables | Categories | ANC4+ | Institutional Delivery | PNC within 24 h | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | AOR (95%CI) | Yes | No | AOR (95%CI) | Yes | No | AOR (95%CI) | ||

| Maternal age at the time of delivery (years) | <20 | 77 | 173 | 1 | 119 | 131 | 1 | 79 | 171 | 1 |

| 20–34 | 293 | 703 | 1.21 (0.64–2.28) | 416 | 580 | 1.42 (0.95–2.13) | 252 | 744 | 0.82 (0.49–1.37) | |

| 35–49 | 47 | 138 | 1.07 (0.39–2.98) | 67 | 118 | 1.16 (0.68–1.96) | 48 | 137 | 0.68 (0.28–1.63) | |

| Residence | Rural | 303 | 872 | 1 | 414 | 761 | 1 | 257 | 918 | 1 |

| Urban | 114 | 142 | 3.59 (1.37–9.46) * | 188 | 68 | 3.17 (1.23–8.18) * | 122 | 134 | 1.53 (0.82–2.87) | |

| Region | Afar | 108 | 279 | 1 | 105 | 282 | 1 | 77 | 310 | 1 |

| Somali | 30 | 311 | 0.26 (0.13–0.54) ** | 71 | 270 | 0.71 (0.36–1.40) | 30 | 311 | 0.43 (0.24–0.78) * | |

| Benishangul-Gumuz | 187 | 182 | 2.00 (1.11–3.60) * | 231 | 138 | 4.70 (1.95–11.32) ** | 151 | 218 | 2.23 (1.16–4.28) * | |

| Gambela | 92 | 242 | 0.41 (0.21–0.79) * | 195 | 139 | 2.61 (1.20–5.69) * | 121 | 213 | 1.56 (0.86–2.82) | |

| Marital status | Not married/not living with partner | 71 | 54 | 1 | 47 | 78 | 1 | |||

| Married/living with partner | 531 | 775 | 0.58 (0.28–1.19) | 332 | 974 | 1.02 (0.57–1.81) | ||||

| Highest level of maternal education | No education | 187 | 667 | 1 | 239 | 615 | 1 | 147 | 707 | 1 |

| Primary | 168 | 251 | 2.11 (1.31–3.40) ** | 238 | 181 | 1.56 (0.84–2.90) | 146 | 273 | 1.67 (0.90–3.09) | |

| Secondary and higher | 62 | 96 | 2.91 (1.60–5.31) ** | 125 | 33 | 2.82 (0.41–19.36) | 86 | 72 | 4.80 (2.66–8.65) ** | |

| Sex of the head of the household | Male | 305 | 686 | 1 | 413 | 578 | 1 | |||

| Female | 112 | 328 | 0.72 (0.39–1.30) | 189 | 251 | 1.96 (1.26–3.05) * | ||||

| Household wealth index | Poorest | 137 | 637 | 1 | 175 | 599 | 1 | 104 | 670 | 1 |

| Poorer | 78 | 133 | 1.59 (0.76–3.33) | 112 | 99 | 2.24 (1.34–3.75) * | 65 | 146 | 1.14 (0.67–1.92) | |

| Middle | 63 | 92 | 1.36 (0.65–2.84) | 89 | 66 | 1.37 (0.67–2.77) | 57 | 98 | 1.31 (0.69–2.52) | |

| Richer | 64 | 77 | 1.31 (0.65–2.64) | 99 | 42 | 3.42 (1.52–7.68) * | 59 | 82 | 2.91 (0.71–11.99) | |

| Richest | 75 | 75 | 1.02 (0.33–3.18) | 127 | 23 | 6.65 (3.00–14.73) ** | 94 | 56 | 4.55 (1.78–11.57) * | |

| Number of children | 1–2 | 165 | 334 | 1 | 266 | 233 | 1 | 170 | 329 | 1 |

| 3–4 | 100 | 273 | 0.77 (0.42–1.42) | 133 | 240 | 0.43 (0.22–0.86) * | 68 | 305 | 0.88 (0.45–1.73) | |

| >=5 | 152 | 407 | 1.04 (0.59–1.82) | 203 | 356 | 0.92 (0.60–1.40) | 141 | 418 | 2.26 (1.28–3.99) * | |

| Mode of delivery | Vaginal | 350 | 1042 | 1 | ||||||

| Caesarean section | 29 | 10 | 5.48 (1.16–26.00) * | |||||||

| Variables | Categories | Completion of the Continuum of Maternity Care | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | OR (95%CI) | aOR (95%CI) | ||

| Maternal age at the time of delivery (years) | <20 | 39 | 211 | 1 | 1 |

| 20–34 | 134 | 862 | 0.57 (0.41–0.81) * | 0.70 (0.44–1.12) | |

| 35–49 | 25 | 160 | 0.42 (0.25–0.72) * | 0.65 (0.32–1.32) | |

| Residence | Rural | 132 | 1043 | 1 | 1 |

| Urban | 66 | 190 | 3.30 (1.60–6.81) * | 1.80 (0.82–3.91) | |

| Region | Afar | 43 | 344 | 1 | 1 |

| Somali | 8 | 333 | 0.19 (0.06–0.67) * | 0.23 (0.07–0.78) * | |

| Benishangul-Gumuz | 103 | 266 | 3.21 (1.93–5.35) ** | 3.41 (1.65–7.04) * | |

| Gambela | 44 | 290 | 1.47 (0.80–2.70) | 0.67 (0.37–1.21) | |

| Marital status | Not married/not living with partner | 23 | 102 | 1 | 1 |

| Married/living with partner | 175 | 1131 | 0.59 (0.31–1.10) | 0.77 (0.36–1.64) | |

| Highest level of maternal education | No education | 77 | 777 | 1 | 1 |

| Primary | 83 | 336 | 3.88 (2.48–6.07) ** | 1.39 (0.93–2.08) | |

| Secondary and higher | 38 | 120 | 8.57 (3.97–18.52) ** | 2.12 (1.13–4.00) * | |

| Sex of the head of the household | Male | 140 | 851 | 1 | 1 |

| Female | 58 | 382 | 0.48 (0.28–0.85) * | 0.96 (0.45–2.05) | |

| Household wealth index | Poorest | 46 | 728 | 1 | 1 |

| Poorer | 32 | 179 | 2.94 (1.51–5.72) * | 1.20 (0.68–2.13) | |

| Middle | 34 | 121 | 4.42 (2.01–9.71) ** | 1.58 (0.74–3.38) | |

| Richer | 33 | 108 | 4.44 (2.03–9.72) ** | 1.63 (0.76–3.50) | |

| Richest | 53 | 97 | 11.24 (5.10–24.77) ** | 4.55 (2.04–10.15) ** | |

| Number of children | 1–2 | 90 | 409 | 1 | 1 |

| 3–4 | 36 | 337 | 0.52 (0.27–1.01) | 0.96 (0.46–2.02) | |

| >=5 | 72 | 487 | 0.38 (0.21–0.69) * | 1.26 (0.70–2.28) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hussen, A.M.; Ibrahim, I.M.; Tilahun, B.; Tunçalp, Ö.; Grobbee, D.E.; Browne, J.L. Completion of the Continuum of Maternity Care in the Emerging Regions of Ethiopia: Analysis of the 2019 Demographic and Health Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6320. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20136320

Hussen AM, Ibrahim IM, Tilahun B, Tunçalp Ö, Grobbee DE, Browne JL. Completion of the Continuum of Maternity Care in the Emerging Regions of Ethiopia: Analysis of the 2019 Demographic and Health Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(13):6320. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20136320

Chicago/Turabian StyleHussen, Abdulaziz Mohammed, Ibrahim Mohammed Ibrahim, Binyam Tilahun, Özge Tunçalp, Diederick E. Grobbee, and Joyce L. Browne. 2023. "Completion of the Continuum of Maternity Care in the Emerging Regions of Ethiopia: Analysis of the 2019 Demographic and Health Survey" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 13: 6320. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20136320

APA StyleHussen, A. M., Ibrahim, I. M., Tilahun, B., Tunçalp, Ö., Grobbee, D. E., & Browne, J. L. (2023). Completion of the Continuum of Maternity Care in the Emerging Regions of Ethiopia: Analysis of the 2019 Demographic and Health Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(13), 6320. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20136320