Is It Correct to Consider Caustic Ingestion as a Nonviolent Method of Suicide? A Retrospective Analysis and Psychological Considerations

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

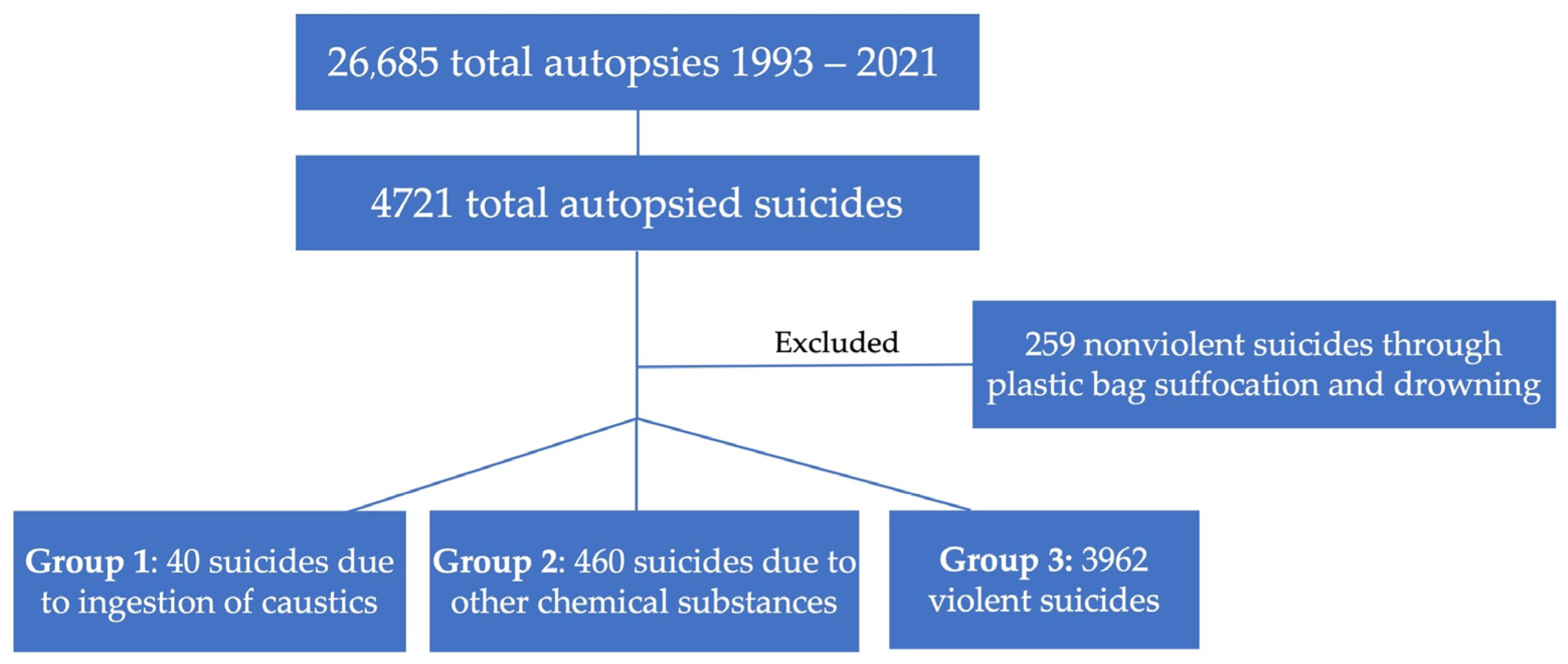

- We first wanted to investigate the differences in terms of socio-demographic, clinical and suicide-related features between caustic ingestion and other chemical ingestion. In research, caustic ingestion and chemical ingestion are commonly treated as the same suicide method, although the similarities and differences between these methods have not yet been explored in depth.

- (2)

- In the second analysis, we compared caustic ingestion victims to violent suicides to better understand the relationship between these two suicide methods. Similar to step (1), we analyzed socio-demographic, clinical and suicide-related features.

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Caustic vs. Chemical Suicides

3.1.1. Socio-Demographic Features

3.1.2. Clinical Features

3.1.3. Suicide-Related Features

3.1.4. Univariate Logistic Regression

3.2. Caustic vs. Violent Suicides

3.2.1. Socio-Demographic Features

3.2.2. Clinical Features

3.2.3. Suicide-Related Features

3.2.4. Univariate Logistic Regression

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Italian Institute of Statistics. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/archivio/203366 (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- World Health Organization. Suicide Worldwide in 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240026643 (accessed on 13 February 2023).

- Currier, D.; Mann, J.J. Stress, Genes and the Biology of Suicidal Behavior. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2008, 31, 247–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souery, D.; Oswald, P.; Linkowski, P.; Mendlewicz, J. Molecular genetics in the analysis of suicide. Ann. Med. 2003, 35, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carballo, J.J.; Llorente, C.; Kehrmann, L.; Flamarique, I.; Zuddas, A.; Purper-Ouakil, D.; Hoekstra, P.J.; Coghill, D.; Schulze, U.M.E.; Dittmann, R.W.; et al. Psychosocial risk factors for suicidality in children and adolescents. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2019, 29, 759–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conner, K.R.; Duberstein, P.R.; Conwell, Y.; Seidlitz, L.; Caine, E.D. Psychological Vulnerability to Completed Suicide: A Review of Empirical Studies. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 2001, 31, 367–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorlyn, M. Impulsivity in the prediction of suicidal behavior in adolescent population. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2005, 17, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turecki, G. Dissecting the suicide phenotype: The role of impulsive-aggressive behaviours: 2003 CCNP Young Investigator Award Paper. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2005, 30, 398–408. [Google Scholar]

- Cano-Montalbán, I.; Quevedo-Blasco, R. Sociodemographic Variables Most Associated with Suicidal Behaviour and Suicide Methods in Europe and America. A Systematic Review. Eur. J. Psychol. Appl. Leg. Context 2018, 10, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åsberg, M.; Träskman, L.; Thorén, P. 5-HIAA in the Cerebrospinal Fluid. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1976, 33, 1193–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.-H.; Jia, C.-X. Completed Suicide with Violent and Non-Violent Methods in Rural Shandong, China: A Psychological Autopsy Study. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e104333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumais, A.; Lesage, A.D.; Lalovic, A.; Séguin, M.; Tousignant, M.; Chawky, N.; Turecki, G. Is Violent Method of Suicide a Behavioral Marker of Lifetime Aggression? Am. J. Psychiatry 2005, 162, 1375–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runeson, B.; Tidemalm, D.; Dahlin, M.; Lichtenstein, P.; Långström, N. Method of attempted suicide as predictor of subsequent successful suicide: National long term cohort study. BMJ 2010, 341, c3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, J.J.; Apter, A.; Bertolote, J.; Beautrais, A.; Currier, D.; Haas, A.; Hegerl, U.; Lonnqvist, J.; Malone, K.; Marusic, A.; et al. Suicide Prevention Strategies. JAMA 2005, 294, 2064–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giner, L.; Jaussent, I.; Olié, E.; Béziat, S.; Guillaume, S.; Baca-Garcia, E.; Lopez-Castroman, J.; Courtet, P. Violent and Serious Suicide Attempters. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2014, 75, 22230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludwig, B.; Dwivedi, Y. The concept of violent suicide, its underlying trait and neurobiology: A critical perspective. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017, 28, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, R.-T.; Ma, Z.-Y.; Jia, C.-X.; Zhou, L. Completed Suicide with Violent and Non-violent Methods by the Elderly in Rural China: A Psychological Autopsy Study. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maes, M.; Cosyns, P.; Meltzer, H.Y.; De Meyer, F.; Peeters, D. Seasonality in violent suicide but not in nonviolent suicide or homicide. Am. J. Psychiatry 1993, 150, 1380–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sørensen, E.H.; Thorgaard, M.V.; Østergaard, S.D. Male depressive traits in relation to violent suicides or suicide attempts: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 262, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrain, R.; Dardennes, R.; Jollant, F. Risky decision-making in suicide attempters, and the choice of a violent suicidal means: An updated meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 280, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.S. Evaluation and Management of Caustic Injuries from Ingestion of Acid or Alkaline Substances. Clin. Endosc. 2014, 47, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenbacka, M.; Jokinen, J. Violent and non-violent methods of attempted and completed suicide in Swedish young men: The role of early risk factors. BMC Psychiatry 2015, 15, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challine, A.; Maggiori, L.; Katsahian, S.; Corté, H.; Goere, D.; Lazzati, A.; Cattan, P.; Chirica, M. Outcomes Associated with Caustic Ingestion Among Adults in a National Prospective Database in France. JAMA Surg. 2022, 157, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadi, A.B.; Nahandi, M.Z.; Ostadi, A.; Ghorbani, A.; Hallaj, S. Endoscopic, laboratory, and clinical findings and outcomes of caustic ingestion in adults; a retrospective study. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Bed Bench 2022, 15, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutaia, G.; Messina, M.; Rubino, S.; Reitano, E.; Salvaggio, L.; Costanza, I.; Agnello, F.; La Grutta, L.; Midiri, M.; Salvaggio, G.; et al. Caustic ingestion: CT findings of esophageal injuries and thoracic complications. Emerg. Radiol. 2021, 28, 845–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amadasi, A.; Gentile, G.; Rancati, A.; Zoja, R. Macroscopic and histopathological aspects of chemical damage to human tissues depending on the survival time. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2016, 130, 743–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoja, R. Patologia Forense Della Lesività da Causa Chimica. Trattato di Medicina Legale e Scienze Affini ii-Semeiotica Medico Legale; Giusti, G., Ed.; CEDAM: Padova, Italy, 2009; pp. 447–496. [Google Scholar]

- Bohnert, M.; Rothschild, M.A. Complex suicides by self-incineration. Forensic Sci. Int. 2003, 131, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, G.; Galante, N.; Tambuzzi, S.; Zoja, R. A forensic analysis on 53 cases of complex suicides and one complicated assessed at the Bureau of Legal Medicine of Milan (Italy). Forensic Sci. Int. 2021, 319, 110662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcinkowski, T.; Pukacka-Sokolowska, L.; Wojciechowski, T. Planned complex suicide. Forensic Sci. 1974, 3, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1992; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, S.-E.; Geem, Z.W.; Na, K.-S. Development of a Suicide Prediction Model for the Elderly Using Health Screening Data. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beghi, M.; Butera, E.; Cerri, C.G.; Cornaggia, C.M.; Febbo, F.; Mollica, A.; Berardino, G.; Piscitelli, D.; Resta, E.; Logroscino, G.; et al. Suicidal behaviour in older age: A systematic review of risk factors associated to suicide attempts and completed suicides. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 127, 193–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, K.W.; Park, M.H.; Park, G.S.; Jung, P.J.; Joo, Y.E.; Kim, H.S.; Rew, J.S.; Kim, S.J. A clinical study on the upper gastrointestinal tract injury caused by corrosive agent. Korean J. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2001, 23, 82–87. [Google Scholar]

- Yeom, H.J.; Shim, K.N.; Kim, S.E.; Lee, C.B.; Lee, J.S.; Jung, H.K.; Kim, T.H.; Jung, S.A.; Yoo, K.; Moon, I.H. Clinical characteristics, and predisposing factors for complication of caustic injury of the upper digestive tract. Korean J. Med. 2006, 70, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsirigotis, K.; Gruszczynski, W.; Tsirigotis-Woloszczak, M. Gender differentiation in methods of suicide attempts. Experiment 2011, 17, PH65–PH70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quan, H.; Arboleda-Flórez, J.; Fick, G.H.; Stuart, H.L.; Love, E.J. Association between physical illness and suicide among the elderly. Soc. Psychiatry 2002, 37, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gürhan, N.; Beşer, N.G.; Polat, Ü.; Koç, M. Suicide risk and depression in individuals with chronic illness. Community Ment. Health J. 2019, 55, 840–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuong, Q.-H.; Le, T.-T.; Jin, R.; Van Khuc, Q.; Nguyen, H.-S.; Vuong, T.-T.; Nguyen, M.-H. Near-Suicide Phenomenon: An Investigation into the Psychology of Patients with Serious Illnesses Withdrawing from Treatment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Törő, K.; Pollak, S. Complex suicide versus complicated suicide. Forensic Sci. Int. 2009, 184, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brådvik, L. Violent and Nonviolent Methods of Suicide: Different Patterns May Be Found in Men and Women with Severe Depression. Arch. Suicide Res. 2007, 11, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddleston, M.; Gunnell, D.; Karunarathne, A.; De Silva, D.; Sheriff, M.H.R.; Buckley, N. Epidemiology of intentional self-poisoning in rural Sri Lanka. Br. J. Psychiatry 2005, 187, 583–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conwell, Y.; Duberstein, P.R.; Caine, E.D. Risk factors for suicide in later life. Biol. Psychiatry 2002, 52, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, J.L. Methods of suicide. In Assessment and Prediction of Suicide; Maris, R.W., Berman, A.L., Maltsberger, J.T., Yufit, R.I., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 381–397. [Google Scholar]

| Category | Chemical | Common Name | Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strong acids (pH < 2) | sulfuric acid | vitriol | detergent; in batteries |

| hydrochloric acid | muriatic | detergent | |

| nitric acid | etching | detergent | |

| phosphoric acid | detergent | ||

| oxalic acid | anti-rust | ||

| Strong bases (pH > 12) | sodium hydroxide | caustic soda | detergent |

| potassium hydroxide | caustic potash | detergent | |

| ammonium hydroxide | ammonia | detergent | |

| Oxidizing agents | sodium hypochlorite | bleach | whitener |

| phenols | |||

| tincture of iodine | |||

| hydrogen peroxide | hydrogen peroxide | whitener | |

| potassium permanganate |

| Variables | Group 1 (n = 40) n (%) or Mean ± SD | Group 2 (n = 460) n (%) or Mean ± SD | Group 1–2 Statistics Chi-2 (df), p or Mann-Whitney U Test, p | Group 3 (n = 3962) n (%) or Mean ± SD | Group 1–3 Statistics Chi-2 (df), p or Mann-Whitney U Test, p | Total Sample (n = 4462) n (%) or Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEX | 2.83 (1), 0.09 | 11.06 (1), 0.001 | ||||

| Men | 19 (47.5%) | 281 (61.1%) | 2830 (71.4%) | 3130 (70.1%) | ||

| Women | 21 (52.5%) | 179 (38.9%) | 1132 (28.6) | 1332 (29.9%) | ||

| AGE | 56.82 ± 16.36 | 47.43 ± 16.16 | −3.56, <0.001 | 51.73 ± 19.31 | −1.83, 0.07 | 51.33 ± 19.03 |

| ETHNICITY | 0.11 (1), 0.74 | 0.54 (1), 0.46 | ||||

| WHITE CAUCASIAN | 39 (97.5%) | 444 (96.5%) | 3731 (94.9%) | 4214 (94.4%) | ||

| Albanian | - | - | 17 (0.4%) | 17 (0.4%) | ||

| Austrian | - | - | 2 (0.05%) | 2 (0.05%) | ||

| American | - | 1 (0.2%) | 3 (0.08%) | 4 (0.09%) | ||

| Bosnian | - | - | 2 (0.05%) | 2 (0.05%) | ||

| Bulgarian | - | - | 5 (0.1%) | 5 (0.1%) | ||

| Canadian | - | - | 1 (0.03%) | 1 (0.02%) | ||

| Czech | - | - | 2 (0.05%) | 2 (0.05%) | ||

| Croatian | - | - | 3 (0.08%) | 3 (0.07%) | ||

| Danish | - | 1 (0.2%) | - | 1 (0.02%) | ||

| English | - | 4 (0.9%) | 17 (0.4%) | 21 (0.05%) | ||

| Estonian | - | - | 2 (0.05%) | 2 (0.05%) | ||

| Finnish | - | 1 (0.2%) | 1 (0.03%) | 2 (0.05%) | ||

| French | - | - | 8 (0.2%) | 8 (0.02%) | ||

| Georgian | - | - | 1 (0.03%) | 1 (0.02%) | ||

| German | 1 (2.5%) | 4 (0.9%) | 15 (0.4%) | 20 (0.05%) | ||

| Greek | - | 1 (0.2%) | 3 (0.08%) | 4 (0.09%) | ||

| Hungarian | - | 1 (0.2%) | 2 (0.05%) | 3 (0.07%) | ||

| Italian | 37 (92.5) | 419 (91.1%) | 3549 (89.6%) | 4005 (89.8%) | ||

| Latvian | 1 (2.5%) | - | 2 (0.05%) | 3 (0.07%) | ||

| Maltese | - | - | 2 (0.05%) | 2 (0.05%) | ||

| Norwegian | - | 2 (0.4%) | 1 (0.03%) | 3 (0.07%) | ||

| Dutch | - | - | 3 (0.1%) | 3 (0.07%) | ||

| Polish | - | 3 (0.7%) | 8 (0.2%) | 11 (0.2%) | ||

| Poland | - | - | 1 (0.03%) | 1 (0.02%) | ||

| Portuguese | - | - | 3 (0.08%) | 3 (0.07%) | ||

| Romanian | - | 2 (0.4%) | 33 (0.8%) | 35 (0.8%) | ||

| Russian | - | 1 (0.2%) | 3 (0.08%) | 4 (0.09%) | ||

| Slovak | - | 2 (0.4%) | - | 2 (0.05%) | ||

| Slovenian | - | - | 3 (0.08%) | 3 (0.07%) | ||

| Somali | - | - | 1 (0.03%) | 1 (0.02%) | ||

| Spanish | - | 1 (0.2%) | 14 (0.4%) | 15 (0.3%) | ||

| Swedish | - | - | 2 (0.05%) | 2 (0.05%) | ||

| Swiss | - | - | 3 (0.08%) | 3 (0.07%) | ||

| Ukrainian | - | 1 (0.2%) | 19 (0.5%) | 20 (0.5%) | ||

| OTHER ETHNICITIES | 1 (2.5%) | 16 (3.5%) | 199 (5.1%) | 216 (4.8%) | ||

| Afghan | - | - | 2 (0.05%) | 2 (0.05%) | ||

| Algerian | - | 1 (0.2%) | 5 (0.1%) | 6 (0.1%) | ||

| Angolan | - | - | 1 (0.03%) | 1 (0.02%) | ||

| Arab | 1 (2.5%) | 1 (0.2%) | 11 (0.3%) | 13 (0.3%) | ||

| Argentinian | - | 1 (0.2%) | 2 (0.05%) | 3 (0.07%) | ||

| Armenian | - | - | 1 (0.03%) | 1 (0.02%) | ||

| Bangladeshi | - | - | 4 (0.1%) | 4 (0.09%) | ||

| Bolivian | - | - | 3 (0.08%) | 3 (0.07%) | ||

| Brazilian | - | 1 (0.2%) | 8 (0.2%) | 9 (0.2%) | ||

| Burundian | - | - | 1 (0.03%) | 1 (0.02%) | ||

| Chilean | - | - | 4 (0.1%) | 4 (0.09%) | ||

| Chinese | - | 1 (0.2%) | 12 (0.3%) | 13 (0.3%) | ||

| Colombian | - | - | 3 (0.08%) | 3 (0.07%) | ||

| Korean | - | - | 4 (0.1%) | 4 (0.09%) | ||

| Cuban | - | - | 6 (0.2%) | 6 (0.1%) | ||

| Ecuadorian | - | 1 (0.2%) | 4 (0.1%) | 5 (0.1%) | ||

| Egyptian | - | - | 15 (0.4%) | 15 (0.03%) | ||

| Eritrean | - | - | 5 (0.1%) | 5 (0.1%) | ||

| Ethiopian | - | - | 4 (0.1%) | 4 (0.09%) | ||

| Philippine | - | - | 15 (0.4%) | 15 (0.03%) | ||

| Gambles | - | - | 1 (0.03%) | 1 (0.02%) | ||

| Ghanaian | - | - | 1 (0.03%) | 1 (0.02%) | ||

| Japanese | - | - | 2 (0.05%) | 2 (0.05%) | ||

| Guinean | - | - | 1 (0.03%) | 1 (0.02%) | ||

| Haitian | - | - | 1 (0.03%) | 1 (0.02%) | ||

| Indian | - | 1 (0.2%) | 5 (0.1%) | 6 (0.1%) | ||

| Indonesian | - | - | 1 (0.03%) | 1 (0.02%) | ||

| Iranian | - | - | 3 (0.08%) | 3 (0.07%) | ||

| Ivorian | - | - | 1 (0.03%) | 1 (0.02%) | ||

| Kazaks | - | 1 (0.2%) | - | 1 (0.02%) | ||

| Kenyan | - | - | 1 (0.03%) | 1 (0.02%) | ||

| Malian | - | - | 4 (0.1%) | 4 (0.09%) | ||

| Moroccan | - | 3 (0.7%) | 15 (0.4%) | 18 (0.04%) | ||

| Moldavian | - | - | 5 (0.1%) | 5 (0.1%) | ||

| Mozambican | - | - | 1 (0.03%) | 1 (0.02%) | ||

| Nepalese | - | - | 1 (0.03%) | 1 (0.02%) | ||

| Nigerian | - | 2 (0.4%) | 3 (0.08%) | 5 (0.1%) | ||

| Pakistani | - | - | 2 (0.05%) | 2 (0.05%) | ||

| Paraguayan | - | - | 1 (0.03%) | 1 (0.02%) | ||

| Peruvian | - | 3 (0.7%) | 10 (0.3%) | 13 (0.3%) | ||

| Salvadoran | - | - | 5 (0.1%) | 5 (0.1%) | ||

| Senegalese | - | - | 3 (0.08%) | 3 (0.07%) | ||

| Sinhalese | - | - | 9 (0.2%) | 9 (0.2%) | ||

| Tunisian | - | - | 3 (0.08%) | 3 (0.07%) | ||

| Turkish | - | - | 7 (0.2%) | 7 (0.02%) | ||

| Venezuelan | - | - | 1 (0.03%) | 1 (0.02%) | ||

| Zambezian | - | - | 2 (0.05%) | 2 (0.05%) |

| Variables | Group 1 (n = 40) n (%) or Mean ± SD | Group 2 (n = 460) n (%) or Mean ± SD | Group 1–2 Statistics Chi-2 (df), p or Mann-Whitney U test, p | Group 3 (n = 3962) n (%) or Mean ± SD | Group 1–3 Statistics Chi-2 (df), p or Mann-Whitney U test, p | Total Sample (n = 4462) n (%) or Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEDICAL HISTORY | 36 (90%) | 366 (79.6%) | 2.54 (1), 0.11 | 3098 (78.2%) | 3.25 (1), 0.07 | 3500 (78.4%) |

| SINGLE DISEASE | 20 (55.6%) | 242 (66.1%) | 1.61 (1), 0.2 | 2103 (67.9%) | 2.48 (1), 0.12 | 2365 (53%) |

| MULTIPLE DISEASE | 16 (44.4%) | 124 (33.9%) | 995 (32.1%) | 1135 (25.4%) | ||

| MEAN NUMBER OF DISEASES | 1.58 ± 1.2 | 1.18 ± 0.9 | −2.14, 0.03 | 1.11 ± 0.85 | −2.63, 0.009 | 1.12 ± 0.86 |

| PSYCHIATRIC DISORDER | 33 (82.5%) a | 309 (67.2%) a | 4.0 (1), 0.05 b | 2564 (64.7%) a | 5.5 (1), 0.02 b | 2906 (65.1%) a |

| Depression | 28 (70%) | 249 (54.1%) | 2114 (53.4%) | 2391 (53.5%) | ||

| Bipolar Disorder | 1 (2.5%) | 9 (2%) | 88 (2.2%) | 98 (2.2%) | ||

| Psychotic Disorder | 5 (12.5%) | 36 (7.8%) | 267 (6.7%) | 308 (6.9%) | ||

| Anorexia Nervosa | - | 6 (1.3%) | 23 (0.6%) | 29 (0.6%) | ||

| Personality Disorder | - | 4 (0.9%) | - | 4 (0.1%) | ||

| Anxiety Disorder | - | 4 (0.9%) | 91 (2.3%) | 95 (2.1%) | ||

| Alcoholism | 2 (5%) | 24 (5.2%) | 163 (4.1%) | 189 (4.2%) | ||

| Addiction | - | 34 (7.4%) | 195 (4.9%) | 229 (5.1%) | ||

| Organic mental disorders (Autism, Mental retardation, Dementia) | - | 1 (0.2%) | 8 (0.2%) | 9 (0.2%) | ||

| Multiple psychiatric disorders | 3 (7.5%) | 47 (10.2%) | 339 (8.6%) | 389 (18.7%) | ||

| MEAN NUMBER OF PSYCHIATRIC DISORDERS | 0.9 ± 0.5 | 0.8 ± 0.68 | −1.41, 0.16 | 0.7 ± 0.64 | −1.91, 0.06 | 0.8 ± 0.64 |

| ORGANIC DISEASE | 16 (40%) a | 129 (28%) a | 2.56 (1), 0.11 b | 1089 (27.5%) a | 3.1 (1), 0.08 b | 1234 (27.7%) a |

| Infectious and parasitic diseases | 1 (2.5%) | 23 (5%) | 106 (2.7%) | 130 (2.9%) | ||

| Neoplasms | 3 (7.5%) | 26 (5.7%) | 285 (7.2%) | 314 (7%) | ||

| Endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases | 2 (5%) | 28 (6.1) | 168 (4.2) | 198 (4.4%) | ||

| Diseases of the nervous system | 3 (7.5%) | 17 (3.7%) | 111 (2.8) | 131 (2.9%) | ||

| Diseases of the eye and adnexa | 1 (2.5%) | 2 (0.4%) | 28 (0.7%) | 31 (0.7%) | ||

| Diseases of the ear and mastoid process | - | 1 (0.2%) | 4 (0.1%) | 5 (0.1%) | ||

| Diseases of the circulatory system | 6 (15%) | 40 (8.7%) | 428 (10.8%) | 474 (10.6%) | ||

| Diseases of the respiratory system | 1 (2.5%) | 10 (2.2%) | 85 (2.1%) | 96 (2.2%) | ||

| Diseases of the digestive system | 1 (2.5%) | 13 (2.8%) | 60 (1.5%) | 74 (1.7%) | ||

| Diseases of the skin and subcutaneous tissue | - | - | 4 (0.1) | 4 (0.1%) | ||

| Diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue | 1 (2.5%) | 5 (1.1%) | 42 (1.1%) | 48 (1.1%) | ||

| Diseases of the genitourinary system | 1 (2.5%) | - | 23 (0.6%) | 24 (0.5%) | ||

| Congenital malformations, deformations and chromosomal abnormalities | 1 (2.5%) | - | 3 (0.1%) | 4 (0.1%) | ||

| Factors influencing health status and contact with health services | - | 7 (1.5%) | 32 (0.8%) | 39 (0.9%) | ||

| Multiple organic disorders | 5 (12.5%) | 36 (90%) | 276 (8.2%) | 317 (7.1%) | ||

| MEAN NUMBER OF ORGANIC DISEASES | 0.68 ± 1.12 | 0.39 ± 0.7 | −1.67, 0.1 | 0.37 ± 0.67 | −1.85, 0.06 | 0.4 ± 0.7 |

| ANY MEDICATION | 24 (60%) | 264 (57.4%) | 0.10 (1), 0.75 c | 2108 (53.2%) | 0.73 (1), 0.39 | 2396 (53.7%) |

| PSYCHOTROPIC MEDICATION | 21 (52.5%) | 235 (51.1%) | 0.03 (1), 0.86 c | 1726 (43.6%) | 1.29 (1), 0.26 | 1982 (44.4%) |

| OTHER MEDICATION | 5 (12.5%) | 44 (9.6%) | 0.36 (1), 0.55 c | 472 (11.9%) | 0.01 (1), 0.91 | 521 (11.7%) |

| Variables | Group 1 (n = 40) n (%) or Mean ± SD | Group 2 (n = 460) n (%) or Mean ± SD | Group 3 (n = 3962) n (%) or Mean ± SD | Total Sample (n = 4462) n (%) or Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORGANIC DISEASE | 16 (40%) * | 129 (28%) * | 1089 (27.5%) * | 1234 (27.7%) * |

| Infectious and parasitic diseases | ||||

| HIV+ | - | 12 (2.6%) | 47 (1.2%) | 59 (1.3%) |

| AIDS | - | 1 (0.2%) | 8 (0.2%) | 9 (0.2%) |

| Poliomyelitis | - | 2 (0.4%) | 4 (0.1%) | 6 (0.1%) |

| HBV | 1 (2.5%) | - | 8 (0.2%) | 9 (0.2%) |

| HCV | - | 11 (2.4%) | 50 (1.3%) | 61 (1.4%) |

| Neoplasms | ||||

| Tumor cachexia | - | 1 (0.2%) | 1 (0.03%) | 2 (0.05%) |

| Leukemia | - | 1 (0.2%) | 6 (0.2%) | 7 (0.2%) |

| Neoplasms of skin | - | - | 2 (0.1%) | 2 (0.05%) |

| Neoplasms of eye, brain and other parts of central nervous system | - | 2 (0.4%) | 15 (0.4%) | 17 (0.4%) |

| Neoplasms of female genital organs | 2 (5%) | - | 19 (0.5%) | 21 (0.5%) |

| Neoplasms of male genital organs | - | 4 (0.9%) | 37 (0.9%) | 41 (0.9%) |

| Neoplasms of digestive organs | 1 (2.5%) | 6 (1.3%) | 109 (2.8%) | 116 (2.6%) |

| Neoplasms of respiratory and intrathoracic organs | - | 1 (0.2%) | 39 (1%) | 40 (0.9%) |

| Neoplasms of lip, oral cavity and pharynx | - | - | 23 (0.6%) | 23 (0.5%) |

| Neoplasms of breast | - | 5 (1.1%) | 24 (0.6%) | 29 (0.6%) |

| Neoplasms of the bone | - | 3 (0.7%) | 4 (0.1%) | 7 (0.2%) |

| Neoplasms of thyroid and other endocrine glands | - | - | 6 (0.2%) | 6 (0.1%) |

| Endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic diseases | ||||

| Hyperlipidemia/ Dyslipidemia | - | - | 4 (0.1%) | 4 (0.1%) |

| Thyroid dysfunction | - | 1 (0.2%) | 16 (0.4%) | 17 (0.4%) |

| Deficit alfa-1 | - | - | 1 (0.03%) | 1 (0.02%) |

| Obesity | 1 (2.5%) | 2 (0.4%) | 8 (0.2) | 11 (0.2%) |

| Goiter | - | 1 (0.2%) | - | 1 (0.02%) |

| Diabetes | 1 (2.5%) | 22 (4.8%) | 128 (3.2%) | 151 (3.4%) |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 1 (0.2%) | 8 (0.2%) | 9(0.2%) | |

| Cystic fibrosis | - | 1 (0.2%) | 4 (0.1%) | 5 (0.1%) |

| Diseases of the nervous system | ||||

| Epilepsy | 2 (5%) | 12 (2.6%) | 44 (1.1%) | 58 (1.3%) |

| Hemiparesis | 1 (2.5%) | - | 4 (0.1%) | 5 (0.1%) |

| SLA | - | 2 (0.4%) | 7 (0.2%) | 9 (0.2%) |

| Alzheimer’s disease | - | 1 (0.2%) | 15 (0.4%) | 16 (0.4%) |

| Peripheral neuropathy | - | 1 (0.2%) | - | 1 (0.02%) |

| Myelitis | - | 1 (0.2%) | - | 1 (0.02%) |

| Neuropathy of the lower limbs | 1 (2.5%) | 1 (0.2%) | 2 (0.1%) | 4 (0.1%) |

| Headache | - | - | 6 (0.1%) | 6 (0.1%) |

| Corea di Huntington | - | - | 3 (0.1%) | 3 (0.1%) |

| Paralysis | - | - | 8 (0.2%) | 8 (0.2%) |

| Parkinson | - | - | 24 (0.6%) | 24 (0.5%) |

| Diseases of the eye and adnexa | ||||

| Blindness | - | - | 7 (0.2%) | 7 (0.2%) |

| Glaucoma | 1 (2.5%) | 1 (0.2%) | 8 (0.2%) | 10 (0.2%) |

| Maculopathy | - | 1 (0.2%) | 6 (0.2%) | 7 (0.2%) |

| Coronophaty/Retinopathy | - | - | 9 (0.2%) | 9 (0.2%) |

| Diseases of the ear and mastoid process | ||||

| Tympanic perforation | - | 1 (0.2%) | - | 1 (0.02%) |

| Deaf-mutism | - | - | 4 (0.1%) | 4 (0.1%) |

| Diseases of the circulatory system | ||||

| Aneurysm | - | - | 6 (0.2%) | 6 (0.1%) |

| Hypertension/ Hypotension | 3 (7.5%) | - | 209 (5.3%) | 212 (4.8%) |

| Cardiomyopathy | 1 (2.5%) | 18 (3.9%) | 126 (3.2%) | 145 (3.2%) |

| Cardiac Fibrillation | 1 (2.5%) | 1 (0.2%) | 9 (0.2%) | 11 (0.2%) |

| Myocardial infarction | 1 (2.5%) | 1 (0.2%) | 36 (0.9%) | 38 (0.9%) |

| Vasculopathy | - | 1 (0.2%) | 8 (0.2%) | 9 (0.2%) |

| Atherosclerosis | 1 (2.5%) | 1 (0.2%) | 5 (0.1%) | 7 (0.2%) |

| Arrhythmia | - | 2 (0.4%) | 21 (0.5%) | 23 (0.5%) |

| IPA | 1 (2.5%) | 15 (3.3%) | 3 (0.1%) | 19 (0.4%) |

| Stroke | 1 (2.5%) | 1 (0.2%) | 39 (1%) | 41 (0.9%) |

| Valvulopathy | - | 1 (0.2%) | 9 (0.2%) | 10 (0.2%) |

| Varicocele | - | - | 5 (0.1%) | 5 (0.1%) |

| Diseases of the respiratory system | ||||

| Bronchial asthma | 1 (2.5%) | 2 (0.4%) | 35 (0.9%) | 38 (0.9%) |

| COPD - Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease | - | 6 (1.3%) | 25 (0.6%) | 31 (0.7%) |

| Pneumonia | - | 1 (0.2%) | 4 (0.1%) | 5 (0.1%) |

| Bronchitis | - | 1 (0.2%) | 7 (0.2%) | 8 (0.2%) |

| Emphysema | - | - | 17 (0.4%) | 17 (0.4%) |

| Pharyngitis | - | - | 1 (0.03%) | 1 (0.02%) |

| Diseases of the digestive system | ||||

| Gastric ulcer | 1 (2.5%) | 3 (0.7%) | 25 (0.6%) | 29 (0.6%) |

| Diverticulitis | - | 1 (0.2%) | 4 (0.1%) | 5 (0.1%) |

| Gastritis | - | 2 (0.4%) | 5 (0.1%) | 7 (0.2%) |

| Inguinal hernia | - | 2 (0.4%) | 4 (0.1%) | 6 (0.1) |

| Rectal prolapse | - | 1 (0.2%) | - | 1 (0.02%) |

| Gastric band | - | 2 (0.4%) | 1 (0.03%) | 3 (0.1%) |

| Cirrhosis | - | 3 (0.7%) | 10 (0.3%) | 13 (0.3%) |

| Appendicitis | - | - | 9 (0.2%) | 9 (0.2%) |

| Celiac disease | - | - | 2 (0.1%) | 2 (0.05%) |

| Disease of the skin | ||||

| Psoriasis | - | - | 4 (0.1%) | 4 (0.1%) |

| Diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue | ||||

| Paget’s disease | 1 (2.5%) | 1 (0.2%) | - | 2 (0.05%) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 1 (2.5%) | 1 (0.2%) | 5 (0.1%) | 7 (0.2%) |

| Osteoporosis | - | 1 (0.2%) | 10 (0.3%) | 11 (0.2%) |

| Vertebral Fracture | - | 1 (0.2%) | 1 (0.03%) | 2 (0.05%) |

| Hip prosthesis | - | 1 (0.2%) | 7 (0.2%) | 8 (0.2%) |

| Arthritis | 1 (2.5%) | 2 (0.4%) | 12 (0.3%) | 15 (0.3%) |

| Disc herniation | - | 1 (0.2%) | 17 (0.4%) | 18 (0.4%) |

| Diseases of the genitourinary system | ||||

| Prostatic hypertrophy | 1 (2.5%) | - | 17 (0.4%) | 18 (0.4%) |

| Renal failure | - | - | 6 (0.2%) | 6 (0.1%) |

| Congenital malformations, deformations, and chromosomal abnormalities | ||||

| Turner Syndrome | 1 (2.5%) | - | - | 1 (0.02%) |

| Down Syndrome | - | - | 1 (0.03%) | 1 (0.02%) |

| Cystic Ovary Syndrome | - | - | 2 (0.1%) | 2 (0.05%) |

| Factors influencing health status and contact with health services | ||||

| Covid-19 | - | 4 (0.9%) | 15 (0.4%) | 19 (0.4%) |

| Hysterectomy | - | 2 (0.4%) | - | 2 (0.05%) |

| By-pass | - | 1 (0.2%) | 10 (0.3%) | 11 (0.2%) |

| Homeless | - | - | 7 (0.2%) | 7 (0.2%) |

| Variables | Group 1 (n = 40) n (%) or Mean ± SD | Group 2 (n = 460) n (%) or Mean ± SD | Group 1–2 Statistics Chi-2 (df), p or Mann-Whitney U Test, p | Group 3 (n = 3962) n (%) or Mean ± SD | Group 1–3 Statistics Chi-2 (df), p or Mann-Whitney U Test, p | Total Sample (n = 4462) n (%) or Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PREVIOUS SUICIDAL IDEATION | 15 (37.5%) | 180 (39.1%) | 0.04 (1), 0.84 * | 1191 (30.1%) | 1.04 (1), 0.31 * | 1386 (31%) |

| PREVIOUS SUICIDE ATTEMPT(S) | 12 (30%) | 155 (33.7%) | 0.23 (1), 0.64 * | 862 (21.8%) | 1.58 (1), 0.21 * | 1029 (23.1%) |

| SIMPLE SUICIDE | 38 (95%) | 428 (93%) | 0.22 (1), 0.64 | 3918 (98.9%) | 5.27 (1), 0.02 | 3984 (89.3%) |

| COMPLEX SUICIDE | 2 (5%) | 32 (7%) | 46 (1.1%) | 80 (1.8%) |

| Variables | Group 1 (n = 40) n (%) or Mean ± SD | Group 2 (n = 460) n (%) or Mean ± SD | Total Sample (n = 500) n (%) or Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of chemical ingested | |||

| Strong acids | 32 (80%) | - | 32 (0.7%) |

| Strong bases | 4 (10%) | - | 4 (0.08%) |

| Oxidizing agents | 1 (2.5%) | - | 1 (0.02%) |

| Mix of different caustics | 1 (2.5%) | - | 1 (0.02%) |

| Medication | - | 260 (56.5%) | 260 (5.8%) |

| Gas | - | 137 (29.8%) | 137 (3.1%) |

| Drugs | - | 8 (1.7%) | 8 (0.2%) |

| Other chemical agents | - | 6 (1.3%) | 6 (0.1%) |

| Mix of different chemicals | 17 (3.7%) | 17 (3.4%) | |

| Causes of death | |||

| CIRCULATORY FAILURE | 9 (22.5%) | 289 (62.8%) | 298 (59.6%) |

| Acute circulatory insufficiency | 9 (22.5%) | 273 (59.3%) | 282 (56.4%) |

| Acute cardio-respiratory insufficiency | - | 16 (3.5%) | 16 (3.2%) |

| INTOXICATION | 11 (27.5%) | 149 (32.4%) | 160 (32%) |

| Acute caustic intoxication | 11 (27.5%) | - | 11 (2.2%) |

| Gas poisoning | - | 143 (31.1%) | 143 (28.6%) |

| Substance poisoning | - | 6 (1.3%) | 6 (1.2%) |

| ORGANIC INJURY | 20 (50%) | 21 (4.7%) | 41 (8.2%) |

| Visceral injuries from caustic ingestion | 14 (35%) | - | 14 (2.8%) |

| Multiple skeletal and visceral injuries | 1 (2.5%) | 3 (0.7%) | 4 (0.8%) |

| Peritonitis | 1 (2.5%) | 3 (0.7%) | 4(0.8%) |

| Septic state | 4 (10%) | - | 4(0.8%) |

| Edema | - | 5 (1.1%) | 5(1%) |

| Drowning | - | 2 (0.4%) | 2(0.4%) |

| Suffocation | - | 4 (0.9%) | 4(0.8%) |

| Hanging | - | 4 (0.9%) | 4(0.8%) |

| Variables | B | S.E. | Wald | p | Exp(B) | 95% C.I. for Exp(B) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Group 1 vs. Group 2 | |||||||

| Age | 0.033 | 0.011 | 9.509 | 0.002 | 1.033 | 1.012 | 1.055 |

| Number of diseases | 0.151 | 0.173 | 0.763 | 0.382 | 1.163 | 0.828 | 1.634 |

| Psychiatric disorder | 0.678 | 0.462 | 2.157 | 0.142 | 1.970 | 0.797 | 4.867 |

| Constant | −4.860 | 0.707 | 47.236 | <0.001 | 0.008 | ||

| Goodness of fit: chi-square (3) = 16.64, p < 0.001, loglikelihood = 262.13 | |||||||

| Group 1 vs. Group 3 | |||||||

| Gender | 1.168 | 0.331 | 12.470 | <0.001 | 3.214 | 1.681 | 6.145 |

| Number of diseases | 0.427 | 0.172 | 6.149 | 0.013 | 1.532 | 1.094 | 2.147 |

| Psychiatric disorder | 0.415 | 0.448 | 0.857 | 0.355 | 1.515 | 0.629 | 3.648 |

| Inside/outside | 2.084 | 0.485 | 18.446 | <0.001 | 8.033 | 3.104 | 20.788 |

| Constant | −7.448 | 0.615 | 146.842 | <0.001 | 0.001 | ||

| Goodness of fit: chi-square (4) = 46.64, p < 0.001, loglikelihood = 392.18 | |||||||

| Variables | Group 1 (n = 40) n (%) or Mean ± SD | Group 2 (n = 460) n (%) or Mean ± SD | Group 1–2 Statistics Chi-2 (df), p or Mann-Whitney U Test, p | Group 3 (n = 3962) n (%) or Mean ± SD | Group 1–3 Statistics Chi-2 (df), p or Mann-Whitney U Test, p | Total Sample (n = 4462) n (%) or Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INSIDE | 34 (87.2%) | 429 (93.3%) | 1.99 (1), 0.16 | 2026 (51.1%) | 20.09 (1), <0.001 | 2.489 (55.8%) |

| Home | 26 (65%) | 259 (56.3%) | 1527 (38.5%) | 1812 (40.6%) | ||

| Hospital | 8 (20%) | 8 (1.7%) | 182 (4.6%) | 198 (4.4%) | ||

| Work | - | 2 (0.4%) | 136 (3.4%) | 138 (3.1%) | ||

| Car/Garage | - | 136 (29.6%) | 43 (1.1%) | 179 (4%) | ||

| Hotel | - | 16 (3.5%) | 42 (1.1%) | 58 (1.3%) | ||

| Prison | - | 8 (1.7%) | 96 (2.4%) | 104 (2.3%) | ||

| OUTSIDE | 5 (12.8%) | 31 (6.7%) | 1936 (48.9%) | 1972 (44.2%) | ||

| Binaries | - | - | 212 (5.4%) | 212 (4.8%) | ||

| Street | 2 (5%) | 5 (1.1%) | 445 (11.2%) | 452 (10.1%) | ||

| Green/park/field | 1 (2.5%) | 12 (2.6%) | 112 (2.8%) | 125 (2.8%) | ||

| River/Lake | - | 4 (0.9%) | 10 (0.3%) | 14 (0.3%) | ||

| Public Area | 2 (5%) | 10 (2.2%) | 1157 (29.2%) | 1169 (26.2%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gravagnuolo, R.; Tambuzzi, S.; Gentile, G.; Boracchi, M.; Crippa, F.; Madeddu, F.; Zoja, R.; Calati, R. Is It Correct to Consider Caustic Ingestion as a Nonviolent Method of Suicide? A Retrospective Analysis and Psychological Considerations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6270. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20136270

Gravagnuolo R, Tambuzzi S, Gentile G, Boracchi M, Crippa F, Madeddu F, Zoja R, Calati R. Is It Correct to Consider Caustic Ingestion as a Nonviolent Method of Suicide? A Retrospective Analysis and Psychological Considerations. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(13):6270. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20136270

Chicago/Turabian StyleGravagnuolo, Rosa, Stefano Tambuzzi, Guendalina Gentile, Michele Boracchi, Franca Crippa, Fabio Madeddu, Riccardo Zoja, and Raffaella Calati. 2023. "Is It Correct to Consider Caustic Ingestion as a Nonviolent Method of Suicide? A Retrospective Analysis and Psychological Considerations" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 13: 6270. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20136270

APA StyleGravagnuolo, R., Tambuzzi, S., Gentile, G., Boracchi, M., Crippa, F., Madeddu, F., Zoja, R., & Calati, R. (2023). Is It Correct to Consider Caustic Ingestion as a Nonviolent Method of Suicide? A Retrospective Analysis and Psychological Considerations. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(13), 6270. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20136270