Psychosocial Risks among Quebec Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Social Media Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Work-Related Psychosocial Risks during the Pandemic

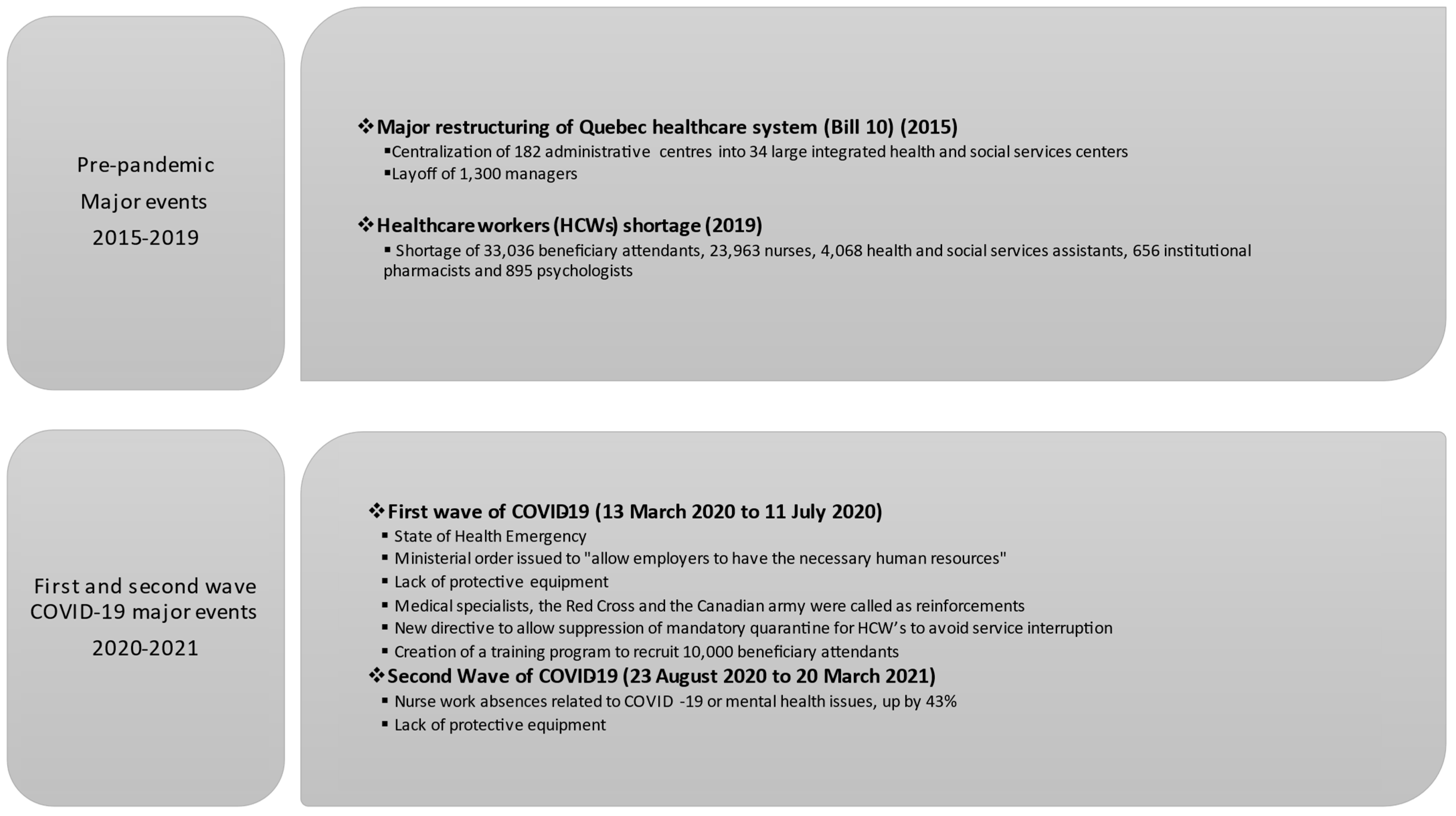

1.2. A Health System Already Vulnerable

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Data Extraction

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. High Workload

“Over 8 days, 5 days of mandatory overtime!!! It makes absolutely no sense, going to work without knowing if you will be able to leave at the end of the shift.”(Second wave)

“We have extra work but not the extra staff. We’ll end up just putting out fires.”(First wave)

“The workload is excessive! Patients are coming in sicker and sicker with complex care complications! We need to hold a heavy load nurse patient ratio! I am discouraged and I only just started my shift!”(Second wave)

3.2. High Emotional Demand

“I have 47 patients and it’s impossible to provide safe and humane care with two teams. Now the number has gone up to 72 patients. So where is the staff to help us?”(First wave)

“Being a nurse and having the obligation to go to work to provide care … our children do not have to suffer contamination because of our professional situation … in any case, I will protect my children from this proximity which will make them suffer from this virus and its really unpleasant symptoms”(first wave)

[…] “Staff moves easily from red zones to green zones! Agencies from Montreal are brought in (in the first wave, an agency from Montreal had contaminated the seniors’ residence next door)” […](second wave)

“I stroked the hair and held the hand of a patient while her husband and daughter looked at her from the other side of the window that separated her from them … I told her again and again that she was not alone, that she could go gently, that her loved ones loved her, that they were close by … but too far away to hug her one last time … it is a sadness beyond words. I saw parents looking at their children behind the window, without being able to say goodbye. Spouses behind the same window silently crying for their love, without being able to kiss them one last time, to say I love you before they pass away.”(First wave)

“The death of a colleague from COVID-19. Another human being with a big heart dead in combat. I can’t take news like this anymore!!! I am a PAB (beneficiary attendant) too, about the same age (49) as him; I also work in a hospital. Where is the protection, are the equipment and procedures sufficient to protect healthy employees … Another falls in combat, one too many RIP to this angel of health. My sincere condolences to the family. Wishing that all are not forgotten…”(first wave)

3.3. Lack of Recognition and Perceived Injustice

“Why aren’t respiratory therapists ever named anywhere! With a respiratory virus, all the more reason to put a spotlight on our profession! As respiratory therapists, we exist and we are on the front lines of danger in terms of being vulnerable to infection! Intubation goes straight to the heart of the matter!”(First wave)

“If instead of calling us guardian angels, the government called us EXPENDABLEat least then, it would be more honest of them seeing as how important they consider us to be.”

(First wave)

“Can someone explain to me how the government is promising full-time jobs and $49,000 salaries to new PABs (beneficiary attendants), even though the [long-term care home] need them, while those already in place do not have these conditions? Is there something I am missing, including respect for the PABs who are already working?”(First wave)

“I don’t know what the government is waiting for to take action and enhance the value of jobs in the health care sector. The task at hand is huge and we deserve safe working conditions, at the very least.”(Second wave)

3.4. Little Support from Supervisors and Colleagues

“It’s unfortunate that we have to fight to get equipment, for our pregnant workers to be able to work in a safe environment, to procure uniforms, but this is the reality we are faced with.”(First wave)

“WoW I am not at all surprised!!! With them you have to hide everything to look good (…) for too long our complaints are not being heard! Arriving at work, running into your supervisor who doesn’t even say hello!”(First wave)

“I deplore our supervisors’ lack of transparency regarding COVID. We are not advised that certain colleagues have COVID and several nurses have it […]. We as the agents are practically not protected we ask for the necessary cleaning gel, virox wipes, etc. We are told that it is for the home care staff to clean their equipment, etc. We are in direct contact with all home care staff. I believe that we have the right to know who is infected in order to protect ourselves. It’s top secret.”(First wave)

Legault (the Premier) lied to nurses and the public. He went from reassuring discourse, in which he said he had enough equipment to get through the crisis, to “I will tell you the truth … We have some equipment to last for 3 to 7 days … Nurses need to disinfect the N95 masks.”(First wave)

“At the hospital we are all a team and we all have our role to play! The important thing is to support each other. We know our worthbecause I’ve noticed there are some whose nerves are frayed and who are starting to lose patience with each other. We must not destroy each other but rather support each other despite our fears and fatigue (…) otherwise we will all be exhausted and our health will take a hit!”

(First wave)

3.5. Work–Family Conflict

“Being a single mom, it won’t be easy during this period when daycares are closed. Although we are passionate about our profession, this time is causing us a real headache because the planning issue is a logistical puzzle.”

3.6. Lack of Decisional Autonomy

“I also think that the real problem, apart from the Barrette reform, is the bad management at the CISSS, which is taking employees for fools since long ago. They don’t give any importance or credibility to employees’ suggestions.”(Second wave)

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

4.2. Practical Implications

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carazo, S.; Pelletier, M.; Talbot, D.; Jauvin, N.; De Serres, G.; Vézina, M. Psychological Distress of Healthcare Workers in Québec (Canada) during the Second and the Third Pandemic Waves. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2022, 64, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, M.; Carazo, S.; Jauvin, N.; Talbot, D.; De Serres, G.; Vézina, M. ÉTude sur la Détresse Psychologique des Travailleurs de la Santé Atteints de la COVID-19 AU Québec Durant la Deuxième Vague Pandémique; Institut National de Santé Publique du Québec: Québec, QC, Canada, 2021; p. 45. [Google Scholar]

- Elshaer, N.S.M.; Moustafa, M.S.A.; Aiad, M.W.; Ramadan, M.I.E. Job Stress and Burnout Syndrome among Critical Care Healthcare Workers. Alex. J. Med. 2018, 54, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.K.; Gandrakota, N.; Cimiotti, J.P.; Ghose, N.; Moore, M.; Ali, M.K. Prevalence of and Factors Associated with Nurse Burnout in the US. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2036469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vézina, M.; Saint-Arnaud, L. L’organisation du travail et la santé mentale des personnes engagées dans un travail émotionnellement exigeant. Travailler 2011, 25, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulia, P.; Mantas, C.; Dimitroula, D.; Mantis, D.; Hyphantis, T. General hospital staff worries, perceived sufficiency of information and associated psychological distress during the A/H1N1 influenza pandemic. BMC Infect. Dis. 2010, 10, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenberg, N.; Docherty, M.; Gnanapragasam, S.; Wessely, S. Managing mental health challenges faced by healthcare workers during COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ 2020, 368, m1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.; Ma, S.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Z.; Hu, J.; Wei, N.; Wu, J.; Du, H.; Chen, T.; Li, R.; et al. Factors Associated with Mental Health Outcomes among Health Care Workers Exposed to Coronavirus Disease 2019. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e203976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Ge, J.; Yang, M.; Feng, J.; Qiao, M.; Jiang, R.; Bi, J.; Zhan, G.; Xu, X.; Wang, L.; et al. Vicarious traumatization in the general public, members, and non-members of medical teams aiding in COVID-19 control. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 88, 916–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T.W.; Yau, J.K.; Chan, C.L.; Kwong, R.S.; Ho, S.M.; Lau, C.C.; Lau, F.L.; Lit, C.H. The psychological impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak on healthcare workers in emergency departments and how they cope. Eur. J. Emerg. Med. 2005, 12, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, V.; Wade, D. Mental health of clinical staff working in high-risk epidemic and pandemic health emergencies a rapid review of the evidence and living meta-analysis. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2021, 56, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, S.; Howard, A.F.; Vanderspank-Wright, B.; Gillis, P.; McLeod, F.; Penner, C.; Haljan, G. The effect of COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of Canadian critical care nurses providing patient care during the early phase pandemic: A mixed method study. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2021, 63, 102999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franklin, P.; Gkiouleka, A. A Scoping Review of Psychosocial Risks to Health Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisely, S.; Warren, N.; McMahon, L.; Dalais, C.; Henry, I.; Siskind, D. Occurrence, prevention, and management of the psychological effects of emerging virus outbreaks on healthcare workers: Rapid review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2020, 369, m1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Guo, L.; Yu, M.; Jiang, W.; Wang, H. The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on medical staff and general public—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 291, 113190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Pablo, G.S.; Vaquerizo-Serrano, J.; Catalan, A.; Arango, C.; Moreno, C.; Ferre, F.; Shin, J.I.; Sullivan, S.; Brondino, N.; Solmi, M.; et al. Impact of coronavirus syndromes on physical and mental health of health care workers: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 275, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Ripoll, M.J.; Meneses-Echavez, J.F.; Ricci-Cabello, I.; Fraile-Navarro, D.; Fiol-deRoque, M.A.; Pastor-Moreno, G.; Castro, A.; Ruiz-Pérez, I.; Zamanillo Campos, R.; Gonçalves-Bradley, D.C. Impact of viral epidemic outbreaks on mental health of healthcare workers: A rapid systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godlee, F. Protect our healthcare workers. BMJ 2020, 369, m1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montemurro, N. The emotional impact of COVID-19: From medical staff to common people. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 87, 23–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronsson, G.; Theorell, T.; Grape, T.; Hammarström, A.; Hogstedt, C.; Marteinsdottir, I.; Skoog, I.; Träskman-Bendz, L.; Hall, C. A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and burnout symptoms. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karasek, R.; Theorell, T. Healthy Work: Stress, Productivity, and the Reconstruction of Working Life; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Niedhammer, I.; Bertrais, S.; Witt, K. Psychosocial work exposures and health outcomes: A meta-review of 72 literature reviews with meta-analysis. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2021, 47, 489–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegrist, J. Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 1996, 1, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theorell, T.; Hammarström, A.; Aronsson, G.; Bendz, L.T.; Grape, T.; Hogstedt, C.; Marteinsdottir, I.; Skoog, I.; Hall, C. A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and depressive symptoms. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Molen, H.F.; Nieuwenhuijsen, K.; Frings-Dresen, M.H.W.; de Groene, G. Work-related psychosocial risk factors for stress-related mental disorders: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e034849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vézina, M.; Pelletier, M.; Brisson, C.; Gilbert-Ouimet, M.; Letellier, M.C. Facteurs de risque psychosociaux. In Manuel d’hygiène du Travail: Du Diagnostic à la Maîtrise des Facteurs de Risque; Chenelière Éducation: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Institut National de Santé Publique du Québec (INSPQ). Risques Psychosociaux du Travail. 2022. Available online: https://www.inspq.qc.ca/risques-psychosociaux-du-travail-et-promotion-de-la-sante-des-travailleurs/risques-psychosociaux-du-travail (accessed on 21 March 2023).

- Madsen, I.E.H.; Nyberg, S.T.; Hanson, L.L.M.; Ferrie, J.E.; Ahola, K.; Alfredsson, L.; Batty, G.D.; Bjorner, J.B.; Borritz, M.; Burr, H.; et al. Job strain as a risk factor for clinical depression: Systematic review and meta-analysis with additional individual participant data. Psychol. Med. 2017, 47, 1342–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amstad, F.T.; Meier, L.L.; Fasel, U.; Elfering, A.; Semmer, N.K. A meta-analysis of work–family conflict and various outcomes with a special emphasis on cross-domain versus matching-domain relations. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollac, M.; Askenazy, P.; Baudelot, C. Mesurer les Facteurs Psychosociaux de Risque AU Travail pour les Maîtriser; Collège d’expertise sur le Suivi des Risques Psycho-Sociaux AU Travail, Ministère du Travail, de l’emploi ET de la Santé: Paris, France, 2011; Available online: https://travail-emploi.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/rapport_SRPST_definitif_rectifie_11_05_10.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2021).

- Anderson-Shaw, L.K.; Zar, F.A. COVID-19, Moral Conflict, Distress, and Dying Alone. J. Bioethical Inq. 2020, 17, 777–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, K.; Watson, D.; Nayani, R.; Tregaskis, O.; Hogg, M.; Etuknwa, A.; Semkina, A. Implementing practices focused on workplace health and psychological wellbeing: A systematic review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 277, 113888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, K.; Abildgaard, J.S. Organizational interventions: A research-based framework for the evaluation of both process and effects. Work. Stress 2013, 27, 278–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institut National de Santé Publique du Québec (INSPQ). Ligne du Temps COVID-19 AU Québec. 2022. Available online: https://www.inspq.qc.ca/covid-19/donnees/ligne-du-temps (accessed on 27 May 2023).

- Barrette, G. Loi Modifiant L’Organisation ET la Gouvernance du Réseau de la Santé ET Des Services Sociaux Notamment Par L’Abolition des Agences Régionales. Chapitre O-7.2. 2015. Available online: https://www.legisquebec.gouv.qc.ca/fr/document/lc/o-7.2 (accessed on 17 April 2023).

- Poirier, L.-R.; Pineault, R.; Gutièrez, M.; Vien, L.-P.; Morisset, J. ÉValuation de la Mise en œUvre du Programme National de Santé Publique 2015–2025—Analyse de L’Impact des Nouveaux Mécanismes de Gouvernance; Institut National de Santé Publique du Québec: Québec, QC, Canada, 2019; p. 51. Available online: https://www.inspq.qc.ca/sites/default/files/publications/2552_evaluation_gouvernance_programme_national_sante_publique_2015_2025.pdf (accessed on 17 April 2023).

- Ministre de la Santé et des Services Sociaux. Arrêté Numéro 2020-015 de la Ministre de la Santé ET des Services Sociaux en Date du 4 Avril 2020 Concernant l’ordonnance de Mesures Visant à Protéger la Santé de la Population dans la Situation de Pandémie de la COVID-19. Loi sur la Santé Publique S-2.2. 2020. Available online: https://cdn-contenu.quebec.ca/cdn-contenu/adm/min/sante-services-sociaux/publications-adm/lois-reglements/AM_numero_2020-015.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2022).

- Porter, I.; Belair-Cirino, M. Plus de 60,000 Travailleurs de la Santé Recherchés. Le Devoir 30 Avril 2019. 2019. Available online: https://www.ledevoir.com/politique/quebec/553217/mot-cle-besoin-de-60-000-travailleurs-de-la-sante-d-ici-5-ans (accessed on 30 August 2022).

- Bourbonnais, R.; Comeau, M.; Vézina, M.; Dion, G. Job strain, psychological distress, and burnout in nurses. Am. J. Ind. Med. 1998, 34, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourbonnais, R.; Mondor, M. Job strain and sickness absence among nurses in the province of Québec. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2001, 39, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministère de la Santé et des Services Sociaux. Rapport Annuel de Gestion du Ministère de la Santé et des Service Sociaux 2019–2020; La Direction des Communications du Ministère de la Santé et des Services Sociaux: Québec, QC, Canada, 2020; p. 72. Available online: https://publications.msss.gouv.qc.ca/msss/document-002682/ (accessed on 17 April 2023).

- Alami, H.; Lehoux, P.; Fleet, R.; Fortin, J.-P.; Liu, J.; Attieh, R.; Cadeddu, S.B.M.; Samri, M.A.; Savoldelli, M.; Ahmed, M.A.A. How Can Health Systems Better Prepare for the Next Pandemic? Lessons Learned from the Management of COVID-19 in Quebec (Canada). Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 671833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrêté Numéro 2020-007 de la Ministre de la Santé et des Services Sociaux en Date du 21 Mars 2020. CONCERNANT L’ordonnance de Mesures Visant à Protéger la Santé de la Population dans la Situation de Pandémie de la COVID-19. 2020. Available online: https://cdn-contenu.quebec.ca/cdn-contenu/adm/min/sante-services-sociaux/publications-adm/lois-reglements/AM_numero_2020-007.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Duchaine, G.; Touzin, C.; Bilodeau, É.; Lacoursière, A. Fuite Vers Le Privé. La Presse 8 Février 2021. 2021. Available online: https://www.lapresse.ca/actualites/covid-19/2021-02-08/infirmieres/fuite-vers-le-prive.php#:~:text=Plus%20de%204000%20infirmi%C3%A8res%20ont,plus%20de%20candidatures%20que%20jamais (accessed on 30 August 2022).

- Nicolakakis, N.; Lafantaisie, M.; Letellier, M.-C.; Biron, C.; Vézina, M.; Jauvin, N.; Vivion, M.; Pelletier, M. Are Organizational Interventions Effective in Protecting Healthcare Worker Mental Health during Epidemics/Pandemics? A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelletier, M.; Nicolakakis, N.; Jauvin, N.; Vivion, M.; Biron, C.; Letellier, M.-C.; Beaupré, R.; Lafantaisie, M.; Vézina, M. Le «Carrefour de la Prévention Organisationnelle»: Un Outil pour Protéger la Santé Mentale du Personnel de la Santé ET des Services Sociaux dans le Contexte de la Pandémie de COVID-19 ET Au-Delà. (Sous Presse); Institut National de Santé Publique du Québec: Québec, QC, Canada, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Franz, D.; Marsh, H.E.; Chen, J.I.; Teo, A.R. Using Facebook for Qualitative Research: A Brief Primer. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e13544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- QSR International Pty Ltd. Nvivo (Relaesed in March 2020). 2021. Available online: https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home (accessed on 25 March 2023).

- Paillé, P.; Mucchielli, A. L’analyse Qualitative en Sciences Humaines et Sociales; Armand Colin: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Vézina, M.; Chénard, C.; Mantha-Bélisle, M.-M. Groupe Scientifique sur l’impact des Conditions ET de L’Organisation du Travail sur la Santé de l’institut National de Santé Publique du Québec. In Grille d’identification de Risques Psychosociaux du Travai; Institut National de Santé Publique du Québec: Québec, QC, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hellemans, C. Charge Émotionnelle. In Dictionnaire des Risques Psychosociaux; Zawieja, P., Guarnieri, F., Eds.; Seuil: Paris, France, 2014; pp. 90–92. [Google Scholar]

- Institut National de Santé Publique du Québec (INSPQ). Tool for Identifying Psychosocial Risk Factors in the Workplace. 2011. Available online: https://www.inspq.qc.ca/en/tool-identifying-psychosocial-risk-factors-workplace (accessed on 27 May 2023).

- Dufour, M.-M.; Bergeron, N.; Rabasa, A.; Guay, S.; Geoffrion, S. Assessment of Psychological Distress in Health-care Workers during and after the First Wave of COVID-19: A Canadian Longitudinal Study. Can. J. Psychiatry 2021, 66, 807–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapisarda, F.; Vallarino, M.; Brousseau-Paradis, C.; De Benedictis, L.; Corbière, M.; Villotti, P.; Cavallini, E.; Briand, C.; Cailhol, L.; Lesage, A. Workplace Factors, Burnout Signs, and Clinical Mental Health Symptoms among Mental Health Workers in Lombardy and Quebec during the First Wave of COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simard, K.; Parent-Lamarche, A. Abusive leadership, psychological well-being, and intention to quit during the COVID-19 pandemic: A moderated mediation analysis among Quebec’s healthcare system workers. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2022, 95, 437–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahiriharsini, A.; Gilbert-Ouimet, M.; Langlois, L.; Biron, C.; Pelletier, J.; Beaulieu, M.; Truchon, M. Associations between psychosocial stressors at work and moral injury in frontline healthcare workers and leaders facing the COVID-19 pandemic in Quebec, Canada: A cross-sectional study. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2022, 155, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauvin, N.; Lazreg, F.; Beaupré, R.; Pelletier, M.; Nikolakakis, N.; Vézina, M.; Mantha-Bélisle, M.M. Être Gestionnaire ou Médecin en Temps de Pandémie: Enjeux de Santé Mentale et Pistes d’action; Institut National de Santé Publique du Québec: Québec, QC, Canada, 2022; p. 35. [Google Scholar]

- Fontanini, R.; Visintini, E.; Rossettini, G.; Caruzzo, D.; Longhini, J.; Palese, A. Italian Nurses’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative analysis of internet posts. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2021, 68, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasdam, S.; Sandberg, H.; Stjernswärd, S.; Jacobsen, F.F.; Grønning, A.H.; Hybholt, L. Nurses’ use of social media during the COVID-19 pandemic—A scoping review. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koren, A.; Alam, M.A.U.; Koneru, S.; DeVito, A.; Abdallah, L.; Liu, B. Nursing Perspectives on the Impacts of COVID-19: Social Media Content Analysis. JMIR Form. Res. 2021, 5, e31358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murri, R.; Segala, F.V.; Del Vecchio, P.; Cingolani, A.; Taddei, E.; Micheli, G.; Fantoni, M. Social media as a tool for scientific updating at the time of COVID pandemic: Results from a national survey in Italy. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0238414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forte, E.C.N.; Pires de Pires, E.D. Nursing appeals on social media in times of coronavirus. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2020, 73, e20200225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossettini, G.; Peressutti, V.; Visintini, E.; Fontanini, R.; Caruzzo, D.; Longhini, J.; Palese, A. Italian nurses’ experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic through social media: A longitudinal mixed methods study of Internet posts. Digit. Health 2022, 8, 205520762211290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Awaisi, A.; O’Carroll, V.; Koraysh, S.; Koummich, S.; Huber, M. Perceptions of who is in the healthcare team? A content analysis of social media posts during COVID-19 pandemic. J. Interprof. Care 2020, 34, 622–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammed, S.; Peter, E.; Killackey, T.; Maciver, J. The “nurse as hero” discourse in the COVID-19 pandemic: A poststructural discourse analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 117, 103887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legault, F. @françcoislegault. in Twitter. 2020. Available online: https://twitter.com/francoislegault?ref_src=twsrc%5Egoogle%7Ctwcamp%5Eserp%7Ctwgr%5Eauthor (accessed on 26 October 2022).

- Vindrola-Padros, C.; Andrews, L.; Dowrick, A.; Djellouli, N.; Fillmore, H.; Gonzalez, E.B.; Javadi, D.; Lewis-Jackson, S.; Manby, L.; Mitchinson, L.; et al. Perceptions and experiences of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e040503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, M.; Perron, A.; Dufour, C.; Marcogliese, E.; Pariseau-Legault, P.; Wright, D.K.; Martin, P.; Carnevale, F.A. Blowing the whistle during the first wave of COVID-19: A case study of Quebec nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 2022, 78, 4135–4149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopreite, M.; Panzarasa, P.; Puliga, M.; Riccaboni, M. Early warnings of COVID-19 outbreaks across Europe from social media. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assemblée Nationale du Québec. Loi Modernisant le Régime de Santé et de Sécurité du Travail (LQ 2021-C27). 2021. Available online: https://canlii.ca/t/6d71v (accessed on 17 April 2023).

- Kuntz, J.C. Resilience in Times of Global Pandemic: Steering Recovery and Thriving Trajectories. Appl. Psychol. 2021, 70, 188–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panel on Research Ethics. TCPS 2 (2018)—Chapter 2: Scope and Approach. Government of Canada. 2019. Available online: https://ethics.gc.ca/eng/tcps2-eptc2_2018_chapter2-chapitre2.html (accessed on 20 January 2020).

| Work-Related Psychosocial Risk Factor | Definitions [51,52] | Themes |

|---|---|---|

| High psychological demands (also known as high workload), including emotional demands. | Excessive amount of work, complexity of the work, time constraints, frequent interruptions and disturbances. Emotional demands refer to the burden experienced given one’s responsibility towards things or people at work or their work roles or mission. | High workload

|

| Low recognition and perceived injustice | Lack of esteem and respect, compensation, job security, or prospects for promotion for efforts and achievements. |

|

| Low workplace social support (a) from supervisors/(b) from colleagues | (a) Inability or inaccessibility of the supervisor to offer practical and emotional support to employees; (b) Lack of team spirit, group cohesion, and assistance from colleagues in task completion. |

|

| Work-life conflict | Difficulty balancing obligations towards work and personal life (social activities, care of children or disabled loved ones). |

|

| Lack of decisional autonomy | Lack of control over one’s work, through a lack of influence on how to do the work or lack of possibility to use or develop one’s skills and creativity on the job. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vivion, M.; Jauvin, N.; Nicolakakis, N.; Pelletier, M.; Letellier, M.-C.; Biron, C. Psychosocial Risks among Quebec Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Social Media Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6116. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20126116

Vivion M, Jauvin N, Nicolakakis N, Pelletier M, Letellier M-C, Biron C. Psychosocial Risks among Quebec Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Social Media Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(12):6116. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20126116

Chicago/Turabian StyleVivion, Maryline, Nathalie Jauvin, Nektaria Nicolakakis, Mariève Pelletier, Marie-Claude Letellier, and Caroline Biron. 2023. "Psychosocial Risks among Quebec Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Social Media Analysis" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 12: 6116. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20126116

APA StyleVivion, M., Jauvin, N., Nicolakakis, N., Pelletier, M., Letellier, M.-C., & Biron, C. (2023). Psychosocial Risks among Quebec Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Social Media Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(12), 6116. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20126116