From Social Rejection to Welfare Oblivion: Health and Mental Health in Juvenile Justice in Brazil, Colombia and Spain

Abstract

1. Introduction

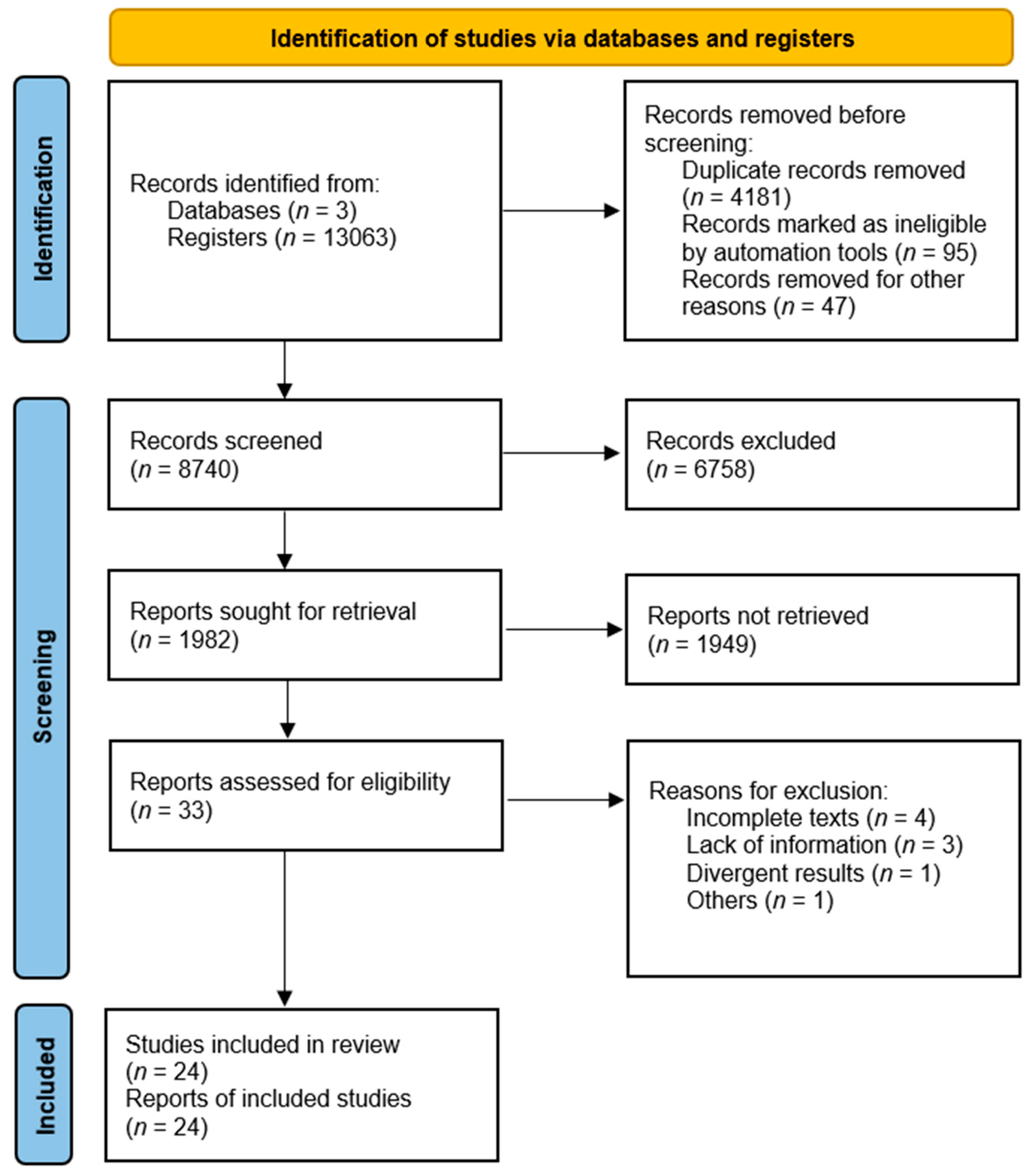

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Action Plan and Study Selection

2.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Identified Documents for the Revision

3.2. Health and Mental Health Care Models in Colombia, Brazil and Spain

3.3. Mental Health Care of Children and Adolescents

3.4. Mental Health Care for Juvenile Offenders

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tarín-Cayuela, M. Las necesidades de formación de las educadoras y los educadores sociales en el ámbito de la infancia y la adolescencia vulnerable. REALIA 2022, 29, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijo, D.; Brazão, N.; Barroso, R.; Da Silva, D.R.; Vagos, P.; Vieira, A.; Lavado, A.; Macedo, M. Mental health problems in male young offenders in custodial versus community based-programs: Implications for juvenile justice interventions. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2016, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Adolescent Mental Health: Mapping Actions of Nongovernmental Organizations and other International Development Organizations; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Escobar-Córdoba, F.; Restrepo-Gualteros, S. Escasez de pediatras en Colombia. Rev. Fac. Med. Univ. Nac. Colomb. 2020, 68, 488–489. [Google Scholar]

- Alcázar-Córcoles, M.A.; Bouso-Saiz, J.C.; Revuelta, J.; Rasmussen, C.A.H.; Lira, E.R.; Calderón-Guerrero, C. Los delincuentes juveniles en Toledo (España) desde el año 2001 a 2012: Características psicosociales, educativas y delictivas. Rev. Espanola de Medicina Leg. 2019, 45, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carl, L.C.; Schmucker, M.; Lösel, F. Predicting attrition and engagement in the treatment of young offenders. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2020, 64, 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castaño-Pulgarín, S.A.; Betancur-Betancur, C. Salud mental de la niñez: Significados y abordajes de profesionales en Medellín, Colombia. Rev. CES Psicol. 2019, 12, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Colombiano de Bienestar Familiar. Resultados Nacionales de la Encuesta de Caracterización Poblacional; SRPA: Bogotá, Colombia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dimenstein, M. La reforma psiquiátrica y el modelo de atención psicossocial en Brasil: En busca de cuidados continuados e integrados e Salud Mental. Rev. CS. 2013, 2, 43–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Almeida, P.F.; Gérvas, J.; Freire, J.M.; Giovanella, L. Estratégias de integração entre atenção primária à saúde e atenção especializada: Paralelos entre Brasil e Espanha. Saúde Debate 2013, 37, 400–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pati, D.; Lorusso, L.N. How to write a systematic review of the literature. HERD 2018, 11, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, D.; Thompson, A.R. Qualitative Research Methods in Mental Health and Psychotherapy: A Guide for Students and Practitioners; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Picornell-Lucas, A.; Pastor, E. Políticas de Inclusión Social de la Infancia y la Adolescencia: Una Perspectiva Internacional; Ciclo Grupo 5: Madrid, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado-Gallego, M.E.; Vázquez, M.L.; De Moraes-Vanderlei, L. Calidad en los servicios de salud desde los marcos de sentido de diferentes actores sociales en Colombia y Brasil. Rev. Esp. Salud Publica. 2010, 12, 533–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Brazil and Spain. 2019. Available online: https://datos.bancomundial.org/?locations=BR-ES (accessed on 8 April 2023).

- United Nations. Human Development Report 2021–2022; United Nations Development Programme: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Baquero, S.; Pérez, L. Implications of the reform to the Colombian health system in employment conditions, working conditions and mental health status of the health workers: A systematic literature review. In Proceedings of the 21st Congress of the International Ergonomics Association (IEA 2021) Healthcare and Healthy Work, Online, 13–18 June 2021; Black, N.L., Neumann, W.P., Noy, I., Eds.; Chamberlein. Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; Volume IV, pp. 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Lins, R.A.; Guimaraes, M.C.S. Sergio Arouca e a reforma sanitária: Registro na produção científica. In XVII Encontro Nacional de Pesquisa em Ciencia da informaçao; UNESP: Salvador, Brasil, 2016; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, A.M.M.; Lima, L.D.; Machado, C.V. Descentralização e regionalização da política de saúde: Abordagem histórico-comparada entre o Brasil e a Espanha. Cien. Saude Colet. 2018, 23, 2239–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Subirats, I.; Vargas Lorenzo, I.; Mogollón-Pérez, A.S.; Paepe, P.; De Ferreira da Silva, M.R.; Unger, J.P.; Vázquez, M.L. Determinantes del uso de distintos niveles asistenciales en el Sistema General de Seguridad Social en Salud y Sistema Único de Salud en Colombia y Brasil. Gac. Sanit. 2014, 28, 480–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein, D.; Jiménez-Rubio, D. What does the decision to opt for private health insurance reveal about public provision? Gac. Sanit. 2019, 33, 442–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prada-Ríos, S.I.; Pérez-Castaño, A.M.; Rivera-Triviño, A.F. Clasificación de instituciones prestadores de servicios de salud según el sistema de cuentas de la salud de la Organización para la Cooperación y el Desarrollo Económico: El caso de Colombia. Rev. Gerenc. Politicas Salud. 2017, 16, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riveros-Pérez, E.; Amado-González, L.N. Modelo de salud en Colombia: ¿financiamiento basado en seguridad social o en impuestos? Rev. Gerenc. Politicas Salud. 2012, 11, 111–120. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, S.C.; Martínez, A. Social capital and quality of healthcare: The experiences of Brazil and Catalonia. Cien. Saude Colet. 2013, 18, 1871–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerril-Montekio, V.; Medina, G.; Aquino, R. Sistema de salud de Brasil. Salud Publ Mex. 2011, 53, 120–131. [Google Scholar]

- Pan American Health Organization. The Burden of Mental Disorders in the Region of the Americas, 2018; PAHO: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Sanidad, Consumo y Bienestar Social. Recursos Económicos del Sistema Nacional de Salud: Presupuestos Iniciales; Ministerio de Sanidad, Consumo y Bienestar Social: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pan American Health Organization. Regional Status Report on Alcohol and Health in the Americas 2020; PAHO: Washington DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Carbonell, A.; Navarro-Pérez, J.J. The care crisis in Spain: An analysis of the family care situation in mental health from a professional psychosocial perspective. Soc. Work Ment. Health 2019, 17, 743–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pedro Cuesta, J.; Ruiz, J.S.; Roca, M.; Noguer, I. Salud mental y salud pública en España: Vigilancia epidemiológica y prevención. Psiquiatr. Biol. 2016, 23, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarante, P.; Nunes, M.O. A reforma psiquiátrica no SUS e a luta por uma sociedade sem manicômios. Ciênc. Saúde Colet. 2018, 23, 2067–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, D.D.J.; Bosi, M.L. Qualidade do cuidado na Rede de Atenção Psicossocial: Experiências de usuários no Nordeste do Brasil. Physis 2019, 29, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, L.F.; Muñoz, C.X.; Uribe-Restrepo, J.M. La rehabilitación psicosocial en Colombia: La utopía que nos invita a seguir caminando. Av. en Psicol. Latinoam. 2020, 38, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaskel, R.; Gaviria, S.; Espinel, Z.; Taborda, E.; Vanegas, R.; Shultz, J. Mental health in Colombia. BJPsych 2015, 12, 95–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamora-Rondón, D.; Suárez-Acevedo, D.; Bernal-Acevedo, O. Analysis of needs and use of mental healthcare services in Colombia. Rev. Salud Pública. 2019, 21, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herazo, E. La salud mental ante la fragmentación de la salud en Colombia: Entre el posicionamiento en la agenda pública y la recomposición del concepto de salud. Rev. Fac. Nac. Salud Pública. 2014, 32, 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, P.H.A.; Colugnati, F.A.B.; Ronzani, T.M. Avaliação de serviços em saúde mental no Brasil: Revisão sistemática da literatura. Cien. Saude Colet. 2015, 20, 3243–3253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Gómez, R.; Reina, L.L.; Méndez, I.F.; García, J.M.; Briñol, L.G. El psicólogo clínico en los centros de salud. Un trabajo conjunto entre atención primaria y salud mental. Aten Primaria. 2019, 51, 310–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardón-Centeno, N.; Cubillos-Novella, A. La salud mental: Una mirada desde su evolución en la normatividad colombiana. 1960–2012. Rev. Gerenc. Polit. Salud. 2012, 11, 12–38. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshiura, V.T.; De Azevedo-Marques, J.M.; Rzewuska, M.; Vinci, A.L.T.; Sasso, A.M.; Miyoshi, N.S.B.; Furegato, A.R.F.; Lopes-Rijo, R.P.C.; Del-Ben, C.M.; Alves, D. A web-based information system for a regional public mental healthcare service network in Brazil. Int. J. Ment. Health Systems. 2017, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador-Carulla, L.; Costa-Font, J.; Cabas, J.; McDaid, D.; Alonso, J. Evaluating mental health care and policy in Spain. J. Ment. Health Policy Econ. 2010, 13, 73–86. [Google Scholar]

- Gallo, J.; Quiñones, A. Subjetividad, salud mental y neoliberalismo en las políticas públicas de salud en Colombia. Athenea Digit. 2016, 16, 139–168. [Google Scholar]

- Macedo, J.P.; Abreu, M.M.D.; Fontenele, M.G.; Dimenstein, M. A regionalização da saúde mental e os novos desafios da Reforma Psiquiátrica brasileira. Saude e Soc. 2017, 26, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Hospital Beds by Type of Care. Available online: https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=hlth_rs_bds&lang=en (accessed on 11 April 2023).

- Oliveira, T.; Boldrini, T.V. Saúde Mental: Investimento Cresce 200% em 2019. Available online: https://www.anahp.com.br/noticias/noticias-do-mercado/saude-mental-investimento-cresce-200-em-2019 (accessed on 11 April 2023).

- Trapé, T.L.; Campos, R.O. The mental health care model in Brazil: Analyses of the funding, governance processes, and mechanisms of assessment. Rev. Saúde Pública. 2017, 51, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cano, J.F.; González-Díaz, J.M.; Vallejo-Silva, A.; Alzate-García, M.; Córdoba-Rojas, R.N. El rol del psiquiatra colombiano en medio de la pandemia de COVID-19. Rev. Colomb. Psiquiatr. 2021, 50, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Health needs of adolescents; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, R.; McCulloch, A.; Parker, C. Supporting Governments and Policy-Makers: Nations for Mental Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Remschmidt, H.; Van Engeland, H. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry in Europe. In Darmstadt: Steinkopff; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Shatkin, J.P.; Belfer, M.L. The global absence of child and adolescent mental health policy. Child Adolesc. Ment Health 2004, 9, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Atlas: Mental Health Resources in the World, 2001; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Knapp, M.; Wong, G. Economics and mental health: The current scenario. World Psychiatry 2020, 19, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieling, C.; Baker-Henningham, H.; Belfer, M.; Conti, G.; Ertem, I.; Omigbodun, O.; Rohde, L.A.; Srinath, S.; Ulkuer, N.; Rahman, A. Child and adolescent mental health worldwide: Evidence for action. Lancet 2011, 378, 1515–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Restrepo, C.; De Santacruz, C.; Rodriguez, M.N.; Rodríguez, V.; Tamayo, N.; Matallana, D.; González, L.M. Encuesta Nacional de salud mental colombia 2015: Protocolo del estudio. Rev. Colomb. Psiquiatr. 2016, 45, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanegas-Medina, C.R.; De la Espriella-Guerrero, R.A. La institución psiquiátrica en Colombia en el año 2025. Investigación con método Delphi. Rev. Gerenc. Politicas Salud. 2015, 14, 114–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velásquez, M. La Salud Mental y los Derechos de los niños en Tiempos de COVID-19. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana, Medellín, Colombia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Macedo, J.P.; Fontenele, M.G.; Dimenstein, M. Saúde Mental Infantojuvenil: Desafios da regionalização da assistência no Brasil. Rev. Polis e Psique. 2018, 8, 112–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, P.G.G. Saúde mental e direitos humanos: 10 anos da Lei 10.216/2001. Arq Bras Psicol. 2011, 63, 114–121. [Google Scholar]

- Ministério da Saúde. Caminhos para uma Política de saúde Mental Infanto-Juvenil; Ministério da Saúde: Brasilia, Brazil, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Braga, C.P.; D’Oliveira, A.F.P.L. Políticas públicas na atenção à saúde mental de crianças e adolescentes: Percurso histórico e caminhos de participação. Ciênc. Saúde Colet. 2019, 24, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Fraile, P.; Herrera, S. Infancia y salud mental pública en España: Siglo XX y actualidad. Rev. Asoc. Esp. Neuropsiq. 2013, 33, 95–111. [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Fornieles, J. Importancia de la formación en psiquiatría de la infancia y adolescencia. Rev. Psiquiatr. Salud. Ment. 2019, 36, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delfini, P.S.S.; Reis, A.O.A. Articulação entre serviços públicos de saúde nos cuidados voltados à saúde mental infantojuvenil. Cad. Saude Publica. 2012, 28, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, A.D.S.A.; Matsukura, T.S. Adolescentes inseridos em um CAPSi: Alcances e limites deste dispositivo na saúde mental infantojuvenil. Temas Psicol. 2016, 24, 977–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministério da Saúde. Atenção Psicossocial a Crianças e Adolescentes no SUS: Tecendo Redes Para Garantir Direitos; Ministério da Saúde e Conselho Nacional do Ministério Público: Brasilia, Brazil, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Sanidad, Consumo y Bienestar Social. Salud Mental: Organización y Dispositivos; Informe, Ministerio de Sanidad, Consumo y Bienestar Social: Madrid, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- El Sayed, S.; Piquero, A.R.; Schubert, C.A.; Mulvey, E.P.; Pitzer, L.; Piquero, N.L. Assessing the mental health/offending relationship across race/ethnicity in a sample of serious adolescent offenders. Crim. Justice Policy Rev. 2016, 27, 265–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez, V.; Graña-Gómez, J.L.G. Madurez psicosocial y comportamiento delictivo en menores infractores. Psicopatol. Clín. Leg. Forense. 2018, 18, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva, M.C.; Cruz, A.P.M.; Teixeira, M.O. Depression, anxiety, and drug usage history indicators among institutionalized juvenile offenders of Brasilia. Psicol.: Reflex. Crit. 2021, 34, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Hume, M. Review of youth violence in Latin America: Gangs and juvenile justice in perspective, studies of America series, 2009. J. Lat. Am. Stud. 2013, 45, 626–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libreros, D.; Asprilla, Z.; Turizo, M. Líneas de acción para prevenir y controlar la delincuencia juvenil en comunidades vulnerables de Barranquilla-Colombia- y su área metropolitana. Justicia Juris. 2015, 11, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diniz, V.B.F.; McBrien, J.L. Children and drug trafficking in Brazil: Can international humanitarian law provide protections for children involved in drug trafficking? Societies 2022, 12, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Pérez, J.J.; Viera, M.; Calero, J.; Tomás, J.M. Factors in assessing recidivism risk in young offenders. Sustainability. 2020, 12, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, E.; García, J.; Frías, M. Meta-análisis de la reincidencia criminal en menores: Estudio de la investigación española. Rev. Mex. Psicol. 2014, 31, 111–123. [Google Scholar]

- Paula, C.S.; Lauridsen-Ribeiro, E.; Wissow, L.; Bordin, I.A.S.; Evans-Lackor, S. How to improve the mental health care of children andadolescents in Brazil: Actions needed in the public sector. Rev. Bras. Psiquiatr. 2012, 34, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, N.R.; Silva, P.R.F. A atenção em saúde mental aos adolescentes em conflito com a lei no Brasil. Cien. Saude Colet. 2017, 22, 1467–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, D.F.S.S.; Noll, P.R.S.; De Jesus, T.F.; Noll, M. Assessing the mental health of Brazilian students involved in risky behaviors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villanueva, J.; Jaramillo, M.C.; Sotomayor, E.; Gutiérrez-Congote, C.; Torres-Quintero, A. La salud mental en los modelos de atención de adolescentes infractores. Los casos de Colombia, Argentina, Estados Unidos y Canadá. Rev. Universitas Med. 2018, 59, 17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Uribe, N. Problemas del tratamiento legal y terapéutico de las transgresiones juveniles de la ley en Colombia. Pensam. Psicol. 2009, 6, 173–191. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Soto, E.; Pereda, N.; Guilera, G. Uso de servicios de atención psicológica en jóvenes del sistema de protección y justicia juvenil. J. Rev. Psicopatol. Psicol. Clin. 2022, 27, 193–203. [Google Scholar]

- González-Arévalo, A. El papel del psicólogo clínico en la justicia juvenil. Derecho Camb. Social. 2017, 50, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Boscà-Cotovad, M. El menor infractor de internamiento terapéutico. RES Rev. Edu. Social 2017, 25, 203–218. [Google Scholar]

- Carbonell, A.; Pereira, F.; Navarro-Pérez, J.J. Atención a la salud mental en adolescentes en conflicto con la ley: Una revisión comparativa de Brasil y España. Onati Socio-Leg. Ser. 2021, 11, 1413–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holguín, G. Construcción Histórica del Tratamiento Jurídico del Adolescente Infractor de la ley Penal Colombiana (1837–2010). Rev. Crim. 2010, 52, 287–306. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Cely, L.A. Análisis de la Justicia Restaurativa en Materia de Responsabilidad Penal para Adolescentes en Colombia. Anu. Psicol. Jurídica. 2012, 22, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cámara, S. Sanciones en los sistemas de justicia juvenil: Visión comparada (especial referencia a los sistemas de responsabilidad penal de menores de España y Colombia). Der. Camb. Social. 2016, 13, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Perminio, H.B.; Silva, J.R.M.; Serra, A.L.L.; Oliveira, B.G.; Morais, C.M.A.D.; Da Silva, J.P.A.B.; Neto, T.L.D.F. Política nacional de atenção integral a saúde de adolescentes privados de liberdade: Uma análise de sua implementação. Cien. Saude Colet. 2018, 23, 2859–2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, C.S.S.; Alberto, M.F.P.; Silva, E.B.F.L. Vivências nas medidas socioeducativas: Possibilidades para o projeto de vida dos jovens. Rev. Psicol: Ciência Profissão. 2019, 39, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, S.; Ribeiro, F.M.L.; Deslandes, S.F. Saúde mental de adolescentes internados no sistema socioeducativo: Relação entre as equipes das unidades e a rede de saúde mental. Cad. Saude Publica. 2018, 34, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Pérez, J.J.; Botija, M.D.; i Maza, F.X.U. La justicia juvenil en España: Una responsabilidad colectiva Propuestas desde el Trabajo Social. Interacc. Perspectiva. 2016, 6, 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, F.M.B.; Ribeiro, J.M.; Moreira, M.R. A saúde do adolescente privado de liberdade: Um olhar sobre políticas, legislações, normatizações e seus efeitos na atuação institucional. Saúde Debate 2015, 39, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribas, M.; Canalias, O. El adolescente con problemas de Salud mental y adicciones en el sistema de Justicia Juvenil: Aspectos éticos. Bioet. Debate 2017, 23, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ministério da Saúde. Levantamento Nacional da Atenção em Saúde Mental aos Adolescentes Privados de Liberdade e sua Articulação com as Unidades Socioeducativas; Ministério da Saúde: Brasilia, Brazil, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Arango-Dávila, C.A.; Rojas, J.C.; Moreno, M. Análisis de los aspectos asociados a la enfermedad mental en Colombia y la formación en psiquiatría. Rev. Colomb. Psiquiatr. 2008, 37, 538–563. [Google Scholar]

- Scisleski, A.C.C.; Maraschin, C.; Da Silva, R.N. Manicômio em circuito: Os percursos dos jovens e a internação psiquiátrica. Cad. Saude Publica. 2008, 24, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massó, P. Cartografía de heterotopías psicoactivas: Una mirada a los discursos médicos, jurídicos y sociales sobre los usos de drogas. Salud Colect. 2015, 11, 381–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnett, S. Foster care youth and the development of autonomy. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2020, 32, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klodnick, V.; Samuels, G. Building home on a fault line: Aging out of child welfare with a serious mental health diagnosis. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2020, 25, 704–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Bernal, L.A.; Castaño-Pérez, G.A.; Restrepo-Bernal, D.P. Salud mental en Colombia. Un análisis crítico. CES Med. 2018, 32, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa-Gómez, J.D.; Londoño, N.M.; Gallego, M.; Arango, L.I.; Rosso, M. Apoyo mutuo, liderazgo afectivo y experiencia clínica comunitaria acompañamiento psicosocial para la “rehabilitación” de víctimas del conflicto armado. Agora USB 2016, 16, 427–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charak, R.; Ford, J.D.; Modrowski, C.A.; Kerig, P. Polyvictimization, emotion dysregulation, symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder, and behavioral health problems among justice-involved youth: A latent class analysis. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2019, 47, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, A.; Gill, S.D.; Salvador-Carulla, L. The future of community psychiatry and community mental health services. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry. 2020, 33, 375–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Colombia | Brazil | Spain | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 51.5 million | 209.5 million | 46.9 million |

| Current Government | Presidential Republic | Presidential federal republic | Parliamentary monarchy |

| Military dictatorship | 1953–1957 | 1964–1985 | 1939–1975 |

| GDP per capita | 6.104 USD | 7.507 USD | 30.103 USD |

| HDI | 0.752 | 0.761 | 0.893 |

| HDI inequality | 0.595 | 0.574 | 0.765 |

| GDI | 0.725 | 0.695 | 0.788 |

| Colombia | Brazil | Spain | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Legal framework | Constitution of 1991 (arts. 44, 48, 49, 365 and 66) | Constitution of 1988 (arts. 196–200) | Constitution of 1978 (arts. 41 y 43) |

| System creation | Law 100 of 1993, Title II | Law 8080/1990 Unified Health System | Law 14/1986 General Health |

| Governance | Departmental and Capital District | Municipal interfederative | Autonomous Communities |

| System financing | Central Government. Departmental/District and Municipal | Federal, state, and municipal governments | Central and regional governments |

| Public expenditure on health | 2.9% GDP per capita | 3.29% GDP per capita | 6.24% GDP per capita |

| Public expenditure on mental health | 1.4% of health expenditure | 2.3% of health expenditure | 3.3% of health expenditure |

| Focus of care financing | 60% hospital 40% community | 28% hospital 72% community | 51% hospital 49% community |

| Focus of attention | Primary Care | CAPS | Primary Care |

| Psychiatric beds in General Hospitals | 1.1 beds/ 100,000 hab. | 1.6 beds/ 100,000 hab. | 3.6 beds/ 100,000 hab. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carbonell, Á.; Georgieva, S.; Navarro-Pérez, J.-J.; Botija, M. From Social Rejection to Welfare Oblivion: Health and Mental Health in Juvenile Justice in Brazil, Colombia and Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5989. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20115989

Carbonell Á, Georgieva S, Navarro-Pérez J-J, Botija M. From Social Rejection to Welfare Oblivion: Health and Mental Health in Juvenile Justice in Brazil, Colombia and Spain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(11):5989. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20115989

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarbonell, Ángela, Sylvia Georgieva, José-Javier Navarro-Pérez, and Mercedes Botija. 2023. "From Social Rejection to Welfare Oblivion: Health and Mental Health in Juvenile Justice in Brazil, Colombia and Spain" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 11: 5989. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20115989

APA StyleCarbonell, Á., Georgieva, S., Navarro-Pérez, J.-J., & Botija, M. (2023). From Social Rejection to Welfare Oblivion: Health and Mental Health in Juvenile Justice in Brazil, Colombia and Spain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(11), 5989. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20115989