“Where Creator Has My Feet, There I Will Be Responsible”: Place-Making in Urban Environments through Indigenous Food Sovereignty Initiatives

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Community Context

2.2. Theoretical Frameworks and Research Process

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Details of Urban IFS Initiatives

3.2. Interactions between Place and IFS Initiatives

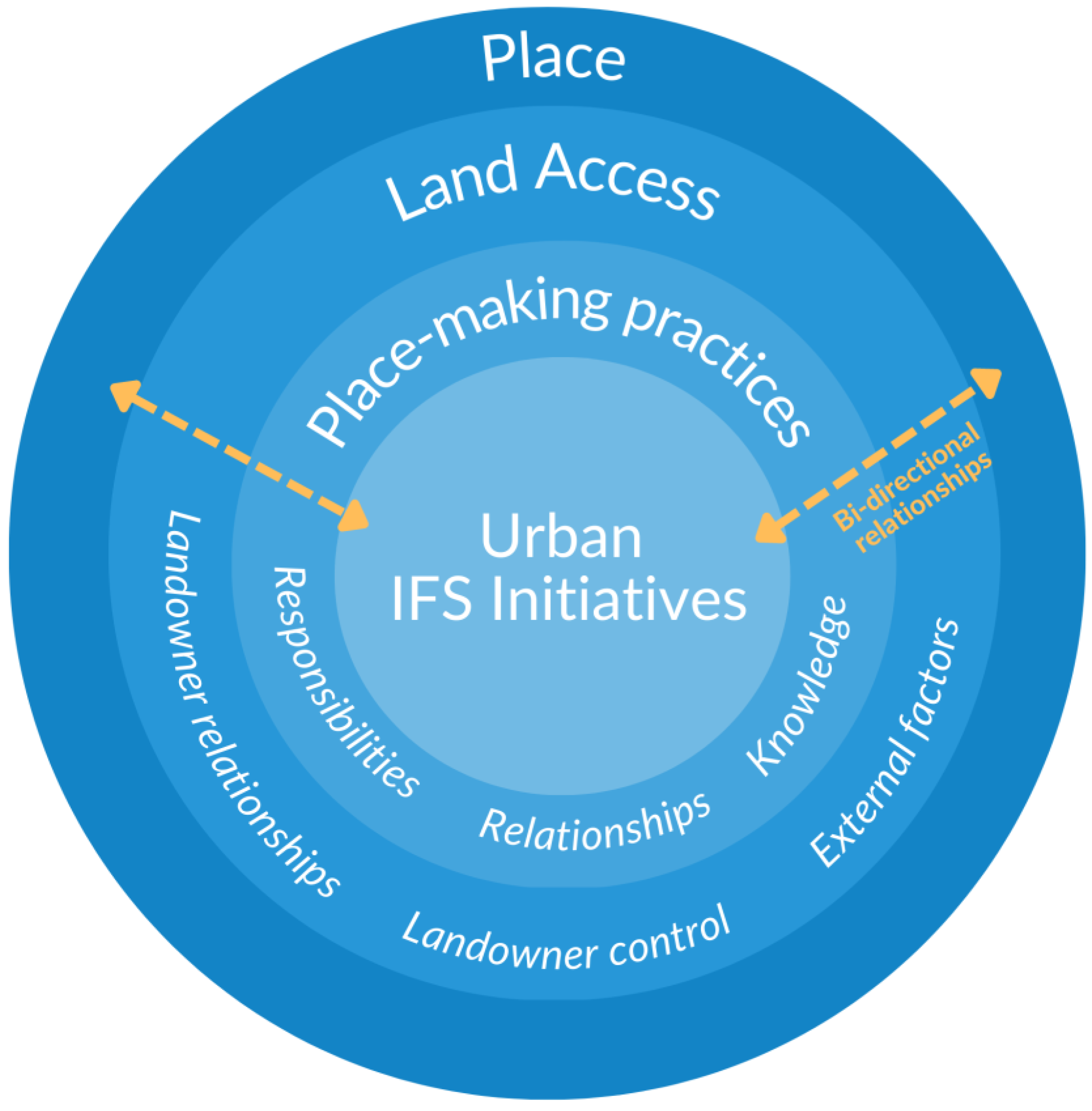

3.3. Land Access

3.3.1. Relationships with Landowners

3.3.2. Landowner Control

The biggest barrier to food sovereignty for Indigenous people in urban centers is control of land. We don’t own land in the western, in the Canadian legal system, so if you don’t own land then we’re just borrowing land to grow food on, or to hunt food on. So, you can’t be sovereign, right? Because at any point in time… that land can be ripped away from you.

3.3.3. External Factors

3.4. Place-Making Practices

3.4.1. Responsibilities

Planting and saving seeds and planting again are these beautiful ways of really being able to witness the unfolding aspect of life. So, I was always really intrigued by that and really excited to be able to use my hands to co-create with, in relationship with these plants, but also in relationship with the Creator and what the Creator had intended for us to be, right? Cause these relationship beings, when we receive from those plants that we are also, that our responsibility is to save those seeds and keep that plant alive.

We want to be responsible for the land and we want to be responsible for the community, right? Our understanding of community comes from the land, we’re rooted in the land and you can’t separate those two things. If we’re really responsible for the land, then we are responsible for the community as well.

3.4.2. Relationships

For example, here the Mohawk white corn … has connection with the people of this territory. I am also growing blue corn … [that], has an even longer historically you know, time wise, connection to Anishinaabe people here in this territory… I am growing Lenape squash, which is from my people from the East Coast, so there is still a connection for me to my people and the land where I, where my family comes from, but that is still brought here and talked about in relationship to, with me and this place, in the urban centre.

3.4.3. Knowledge

So, we’re able to communicate with the plants and understand what they like based on their soil and their water intake. And we’re learning more and more about what they need, and we give what we can, we put down tobacco, we give them water, and I’ve read somewhere that to take from a plant is also sustaining that’s plants needs because that’s what it is grown to do, right? And that’s how some plants continue to grow, they’re eaten and then disposed of elsewhere, and that’s how they germinate and grow. It is a mutually beneficial relationship.

They would take me in the woods and show me ‘this is this, this how you use it, this one’s medicine’ but I didn’t really associate that as traditional food until we started doing the [food sovereignty] stuff ‘cause I just saw them as the forest walks I did with my dad and my grandpa.

[Indigenous people living on-reserve] have many benefits and blessings based on where they’re raised, and we have many benefits and blessings because of where we’re raised. So, I get access to so many different Nations and so many different Nations’ knowledge and so many different Nations traditions. Right? And it’s like I feel like I have a more complete understanding of who Creator is.

I wanted to use that name in some way to reflect what we we’re doing related to the garden because I feel like in the city, in the urban context, we were trying to do something new. We were trying to figure out how to develop our land-based knowledge in a new way.

4. Discussion

4.1. Recommendations for Future Research

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Styres, S.D.; Zinga, D.M. The community-first land-centred theoretical framework: Bringing a good mind to Indigenous education research? Can. J. Educ. 2013, 36, 284–313. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, L.B. Land as Pedagogy: Nishnaabeg intelligence and rebellious transformation. Decoloniz. Indig. Educ. Soc. 2014, 3, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Haig-Brown, C. Decolonizing diaspora: Whose traditional land are we on? In Decolonizing Philosophies of Education, 1st ed.; Ali, A.A., Ed.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 73–90. [Google Scholar]

- Watts, V. Indigenous place-thought & agency amongst humans and non-humans (First Woman and Sky Woman go on a European world tour!). Decoloniz. Indig. Educ. Soc. 2013, 2, 20–34. [Google Scholar]

- Daigle, M. Awawanenitakik: The spatial politics of recognition and relational geographies of Indigenous self-determination. Can. Geogr. 2016, 60, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilpin, E.M.; Hayes, M. A collection of voices: Land-based leadership, community wellness and food knowledge revitalization of the Tsartlip First Nation garden Project. In Indigenous Food Systems: Concepts, Cases, and Conversations; Settee, P., Shukla, S., Eds.; Canadian Scholars: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2020; pp. 101–118. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, K.; Peters, E.J. “You can make a place for it”: Remapping urban First Nations spaces of identity. Environ. Plan D 2005, 23, 395–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatala, A.R.; Njeze, C.; Morton, D.; Pearl, T.; Bird-Naytowhow, K. Land and nature as sources of health and resilience among Indigenous youth in an urban Canadian context: A photovoice exploration. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, A.J.; Pickerill, J. Doings with the land and sea: Decolonising geographies, Indigeneity, and enacting place-agency. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2020, 44, 640–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S. Research is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods; Fernwood Publishing: Black Point, NS, Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Deloria, V., Jr. Power and place equal personality. In Power and Place: Indian Education in America; Deloria, V., Jr., Wildcat, D.P., Eds.; Fulcrum Resources: Boulder, CO, USA, 2001; pp. 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Richmond, C.A.; Ross, N.A.; Richmond, C.A.; Ross, N.A. The determinants of First Nation and Inuit health: A critical population health approach. Health Place 2009, 15, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, A.; Snyder, M.; Wilson, K. Exploring Indigenous youth perspectives of mobility and social relationships: A Photovoice approach. Can. Geogr. 2018, 62, 314–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richmond, C.; Steckley, M.; Neufeld, H.; Kerr, R.B.; Wilson, K.; Dokis, B. First nations food environments: Exploring the role of place, income, and social connection. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2020, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, D.; Castleden, H.; Apostle, R.; Francis, S.; Francis-Strickland, K. Linking land displacement and environmental dispossession to Mi’kmaw health and well-being: Culturally relevant place-based interpretive frameworks matter. Can. Geogr. 2020, 65, 66–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matties, Z. Unsettling settler food movements: Food sovereignty and decolonization in Canada. Cuizine 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settee, P.; Shukla, S. Introduction. In Indigenous Food Systems: Concepts, Cases, and Conversations; Settee, P., Shukla, S., Eds.; Canadian Scholars: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2020; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, D. Indigenous food sovereignty: A model for social learning. In Food Sovereignty in Canada: Creating Just and Sustainable Food Systems; Desmarais, A., Wiebe, N., Eds.; Fernwood Publishing: Black Point, NS, Canada, 2011; pp. 97–113. [Google Scholar]

- Lemke, S.; Delormier, T. Indigenous Peoples’ food systems, nutrition, and gender: Conceptual and methodological considerations. Matern. Child Nutr. 2017, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlowska-Mainville, A. Aki Miijim (Land Food) and the Sovereignty of the Asatiwispe Anishinaabeg Boreal Forest Food System. In Indigenous Food Systems: Concepts, Cases, and Conversations; Settee, P., Shukla, S., Eds.; Canadian Scholars Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2020; pp. 57–81. [Google Scholar]

- Kamal, A.G.; Linklater, R.; Thompson, S.; Dipple, J.; Ithinto Mechisowin Committee. A Recipe for Change: Reclamation of Indigenous Food Sovereignty in O-Pipon-Na-Piwin Cree Nation for Decolonization, Resource Sharing, and Cultural Restoration. Globalizations 2015, 12, 559–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delormier, T.; Horn-Miller, K.; McComber, A.M.; Marquis, K. Reclaiming food security in the Mohawk community of Kahnawà:ke through Haudenosaunee responsibilities. Matern. Child Nutr. 2017, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neufeld, H.; Richmond, C.; Southwest Ontario Aboriginal Health Access Centre. Impacts of place and social spaces on traditional food systems in Southwestern Ontario. Int. J. Indig. Health 2017, 12, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, M.; Wilson, K. ‘Too much moving…there’s always a reason’: Understanding urban Aboriginal peoples’ experiences of mobility and its impact on holistic health. Health Place 2015, 34, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, B.; Jayatilaka, D.; Brown, C.; Varley, L.; Corbett, K.K. “We are not being heard”: Aboriginal perspectives on traditional foods access and food security. J. Environ. Public Health 2012, 2012, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cidro, J.; Adekunle, B.; Peters, E.; Martens, T. Beyond food security: Understanding access to cultural food for urban Indigenous people in Winnipeg as Indigenous food sovereignty. Can. J. Urban Res. 2015, 24, 24–43. [Google Scholar]

- Neufeld, H.T.; Richmond, C. Exploring First Nation Elder women’s relationships with food from social, ecological, and historical perspectives. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2020, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Census Profile, 2016 Census. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/details/page.cfm?Lang=E&Geo1=CSD&Code1=3523008&Geo2=CD&Code2=3523&Data=Count&SearchText=guelph&SearchType=Begins&SearchPR=01&B1=All&TABID=1 (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Jewell, E.M. Social Exposure and Perceptions of Language Importance in Canada’s Urban Indigenous Peoples. Aust. Aborig. Stud. 2016, 5, 99–113. [Google Scholar]

- Wrathall, D.; Wilson, K.; Rosenberg, M.W.; Snyder, M.; Barberstock, S. Long-term trends in health status and determinants of health among the off-reserve Indigenous population in Canada, 1991–2012. Can. Geogr. 2020, 64, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levkoe, C.; Ray, L.; Mclaughlin, J. The Indigenous food circle: Reconciliation and resurgence through food in Northwestern Ontario. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2019, 9, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carli, V. The city as a “Space of Opportunity”: Urban Indigenous Experiences and Community Safety Partnerships. In Well-Being in the Urban Aboriginal Community: Fostering Biimaadiziwin, a National Research Conference on Urban Aboriginal Peoples; Newhouse, D., FitzMaurice, K., McGuire-Adams, T., Daniel, J., Eds.; Thompson Educational Publishing Inc: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2013; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Land Back. A Yellowhead Institute Paper. Available online: https://redpaper.yellowheadinstitute.org/?fbclid=IwAR34LPE3C7PqTdd2LEO9GOlx0LtVptFBhQyvybOUjwf3MggE2EdCKxnckHs (accessed on 12 October 2022).

- Carter, S. Lost Harvests: Prairie Indian Reserve Farmers and Government Policy; McGill-Queen’s University Press: Montreal, QC, Canada, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Neufeld, H.T. Socio-Historical Influences and Impacts on Indigenous Food Systems in Southwestern Ontario: The Experiences of Elder Women living on-and off-reserve. In Indigenous Food Systems: Concepts, Cases, and Conversations; Settee, P., Shukla, S., Eds.; Canadian Scholars: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2020; pp. 251–268. [Google Scholar]

- Rotz, S. ‘They took our beads, it was a fair trade, get over it’: Settler colonial logics, racial hierarchies and material dominance in Canadian agriculture. Geoforum 2017, 82, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban Indigenous People: Not Just Passing through. Congress of Aboriginal Peoples. 2019. Available online: http://www.abo-peoples.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Urban-Indigenous-Report-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Desbiens, C.; Lévesque, C.; Comat, I. “Inventing New Places”: Urban Aboriginal Visibility and the Co-Constitution of Citizenship in Val-d’Or (Québec). City Soc. 2016, 28, 74–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neufeld, H.T.; Xavier, A. The evolution of Haudenosaunee food guidance: Building capacity toward the sustainability of local environments in the community of Six Nations of the Grand River. Can. Food Stud. 2022, 9, 114–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, K.; Pratley, E.; Burnett, K. Eating in the City: A Review of the Literature on Food Insecurity and Indigenous People Living in Urban Spaces. Societies 2016, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouri, L.; Engler-Stringer, R.; Thomson, T.; Wood, M. Food justice in the inner city: Reflection from a program of public health nutrition research in Saskatchewan. In Indigenous Food Systems: Concepts, Cases, and Conversations; Settee, P., Shukla, S., Eds.; Canadian Scholars: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2020; pp. 173–191. [Google Scholar]

- Cyr, M.; Slater, J. Honouring the grandmothers through (re)membering, (re)learning, and (re)vitilizing Metis traditional foods and protocols. Can. Food Stud. 2019, 6, 51–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundel, E.; Chapman, G.E. A decolonizing approach to health promotion in Canada: The case of the Urban Aboriginal Community Kitchen Garden Project. Health Promot. Int. 2010, 25, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peach, L.; Richmond, C.A.; Brunette-Debassige, C. “You can’t just take a piece of Land from the university and build a garden on it”: Exploring Indigenizing space and place in a settler Canadian university context. Geoforum 2020, 114, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miltenburg, E.; Neufeld, H.T.; Anderson, K. Relationality, Responsibility and Reciprocity: Cultivating Indigenous Food Sovereignty within Urban Environments. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, L.; Burnett, K.; Cameron, A.; Joseph, S.; LeBlanc, J.; Parker, B.; Recollet, A.; Sergerie, C. Examining Indigenous food sovereignty as a conceptual framework for health in two urban communities in Northern Ontario, Canada. Glob. Health Promot. 2019, 26, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robin (Martens), T.; Cidro, J. Building cultural identity and Indigenous Food Sovereignty with Indigenous Youth through traditional food access and skills in the city. In Indigenous Food Systems: Concepts, Cases, and Conversations; Settee, P., Shukla, S., Eds.; Canadian Scholars: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2020; pp. 135–151. [Google Scholar]

- Miltenburg, E. “Where Creator has my Feet, There I Will Be Responsible”: Impacts of Place on Urban Indigenous Food Sovereignty Initiatives across Grand River Territory. Master’s Thesis, University of Guelph, Guelph, ON, Canada, 21 April 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Our Watershed, Grand River Conservation Authority. Available online: https://www.grandriver.ca/en/our-watershed/Our-Watershed (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Haudenosaunee Gifts: Contributions to Our Past and Our Common Future. Available online: https://earthtotables.org/essays/haudenosaunee-gifts/ (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Lytwyn, V.P. A Dish with One Spoon: The Shared Hunting Grounds Agreement in the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Valley Region. In Papers of the Twenty Eighth Algonquin Conference; Pentland, D.H., Ed.; University of Manitoba: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 1997; Volume 28, pp. 210–227, 1 December 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Rotondi, M.A.; O’Campo, P.; O’Brien, K.; Firestone, M.; Wolfe, S.H.; Bourgeois, C.; Smylie, J.K. Our Health Counts Toronto: Using respondent-driven sampling to unmask census undercounts of an urban indigenous population in Toronto, Canada. BMJ Open 2017, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban Aboriginal Peoples Study: Main Report, Environics Institute for Survey Research. 2010. Available online: https://www.uaps.ca/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/UAPS-Main-Report.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Aboriginal Health Needs Assessment within the Waterloo Wellington Local Health Integration Network Service Area, John-ston Research Inc., 2010. Available online: https://www.regionofwaterloo.ca/en/regional-government/resources/Reports-Plans--Data/Public-Health-and-Emergency-Services/FirstNation_Metis_Inuit_PopulationProfile.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Smith, L.T. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, 2nd ed.; Zed Books Ltd.: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kovach, M.E. Indigenous Methodologies: Characteristics, Conversations, and Contexts; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Drawson, A.S.; Toombs, E.; Mushquash, C.J. Indigenous research methods: A systematic review. Int. Indig. Policy J. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castleden, H.; Morgan, V.S.; Lamb, C. “I spent the first-year drinking tea”: Exploring Canadian university researchers’ perspectives on community-based participatory research involving Indigenous Peoples. Can. Geogr. 2012, 56, 160–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobias, J.K.; Richmond, C.A.M.; Luginaah, I. Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) with Indigenous Communities: Producing Respectful and Reciprocal Research. J. Empir. Res. Hum. Res. Ethics 2013, 8, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wisahkotewinowak Collective. Available online: https://www.wisahk.ca/ (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- USAI Research Framework. Available online: https://ofifc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/USAI-Research-Framework-Second-Edition.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Lavallée, L.F. Practical application of an Indigenous research framework and two qualitative Indigenous research methods: Sharing circles and Anishnaabe symbol-based reflection. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2009, 8, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Planning and designing qualitative research. In Successful Qualitative Research: A practical Guide for Beginners; Carmichael, M., Clogan, A., Eds.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2013; pp. 42–74. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmonds, P. Unpacking Settler Colonialism’s Urban Strategies: Indigenous Peoples in Victoria, British Colombia, and the Transition to a Settler-Colonial City. Urban Hist. Rev. 2010, 38, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, K.; Xavier, A.L.; Neufeld, H.T. Healthy Roots: Building capacity through shared stories rooted in Haudenosaunee knowledge to promote Indigenous foodways and well-being. Can. Food Stud. 2018, 5, 180–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delormier, T.; Marquis, K. Building Healthy Community Relationships Through Food Security and Food Sovereignty. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2019, 3, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Big-Canoe, K.; Richmond, C.A. Anishinabe youth perceptions about community health: Toward environmental repossession. Health Place 2014, 26, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambtman-Smith, V.; Richmond, C.A. Reimagining Indigenous spaces of healing: Institutional environmental repossession. Turt. Isl. J. Indig. Health 2020, 1, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nightingale, E.; Richmond, C.A. Building structures of environmental repossession to reclaim land, self-determination and Indigenous wellness. Health Place 2021, 73, 102725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- We Rise Together: Achieving Pathway to Target 1 through the Creation of Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas in the Spirit and Practice of Reconciliation, The Indigenous Circle of Experts Report and Recommendations. Available online: https://publications.gc.ca/site/eng/9.852966/publication.html (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Sogorea Te’ Land Trust. Available online: https://sogoreate-landtrust.org/# (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Wires, K.N.; LaRose, J. Sogorea Te’ Land Trust and Indigenous Food Sovereignty in the San Francisco Bay Area. J. Agric. Food Sys. Community Dev. 2019, 9, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuck, E.; Yang, K.W. Decolonization is not a metaphor. Decoloniza. Indig. Edu. Soc. 2012, 1, 1–40. [Google Scholar]

| Urban IFS Initiative | Participant Name or Pseudonym | Indigenous Identity | Locations | Land Access Arrangement(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wisahkotewinowak | Dave | Métis | Kitchener, Waterloo, Guelph, Cambridge | Post-secondary institutions, schoolboard, and a non-profit organization |

| Garrison | First Nations | |||

| Sarina | Métis | |||

| Waterloo Region Indigenous Food Sovereignty Collective | Rachel | First Nations | Kitchener, Waterloo | Private land (residential) |

| Beth | First Nations | |||

| Waterloo Indigenous Student Centre | Lori | Cree-Métis | Waterloo | Post-secondary institution |

| North End Harvest Market | Nookomis | First Nations | Guelph | None |

| Thematic Categories | Themes | Representative Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Land Access | Landowner relationships | “It took three years of asking questions and stuff like that before we were able to get [access to that land].” |

| Landowner control | “The biggest barrier to food sovereignty for Indigenous people in urban centres is control of land… [I] f you don’t own land then we’re just borrowing land to grow food on, or to hunt food on. So, you can’t be sovereign right?” | |

| External factors | “Somebody ripped all our signs down and took all the strawberries” | |

| Place-making Practices | Responsibilities | “We want to be responsible for the land and we want to be responsible for the community, right? ‘Cause our understanding of community comes from the land” |

| Relationships | “I am growing Lenape squash, which is from my people from the East Coast ... but that is still brought here and talked about in relationships to, with me and this place, in the urban centre.” | |

| Knowledge | “[My dad and my grandpa] would take me into the woods and show me ‘this is this, this is how you use it, this one’s medicine’ but I didn’t really associate that as traditional food until we started doing the [food sovereignty] stuff.” |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Miltenburg, E.; Neufeld, H.T.; Perchak, S.; Skene, D. “Where Creator Has My Feet, There I Will Be Responsible”: Place-Making in Urban Environments through Indigenous Food Sovereignty Initiatives. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5970. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20115970

Miltenburg E, Neufeld HT, Perchak S, Skene D. “Where Creator Has My Feet, There I Will Be Responsible”: Place-Making in Urban Environments through Indigenous Food Sovereignty Initiatives. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(11):5970. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20115970

Chicago/Turabian StyleMiltenburg, Elisabeth, Hannah Tait Neufeld, Sarina Perchak, and Dave Skene. 2023. "“Where Creator Has My Feet, There I Will Be Responsible”: Place-Making in Urban Environments through Indigenous Food Sovereignty Initiatives" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 11: 5970. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20115970

APA StyleMiltenburg, E., Neufeld, H. T., Perchak, S., & Skene, D. (2023). “Where Creator Has My Feet, There I Will Be Responsible”: Place-Making in Urban Environments through Indigenous Food Sovereignty Initiatives. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(11), 5970. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20115970