Age, Loneliness, and Social Media Use in Adults during COVID-19: A Latent Profile Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedures

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Indicator Variables Included in the Latent Profile Analysis

2.3.2. Predictor Variables

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Psychometric Properties of the Study Questionnaires

3.2. Latent Profile Analysis

3.3. Demographic Differences among the Profiles

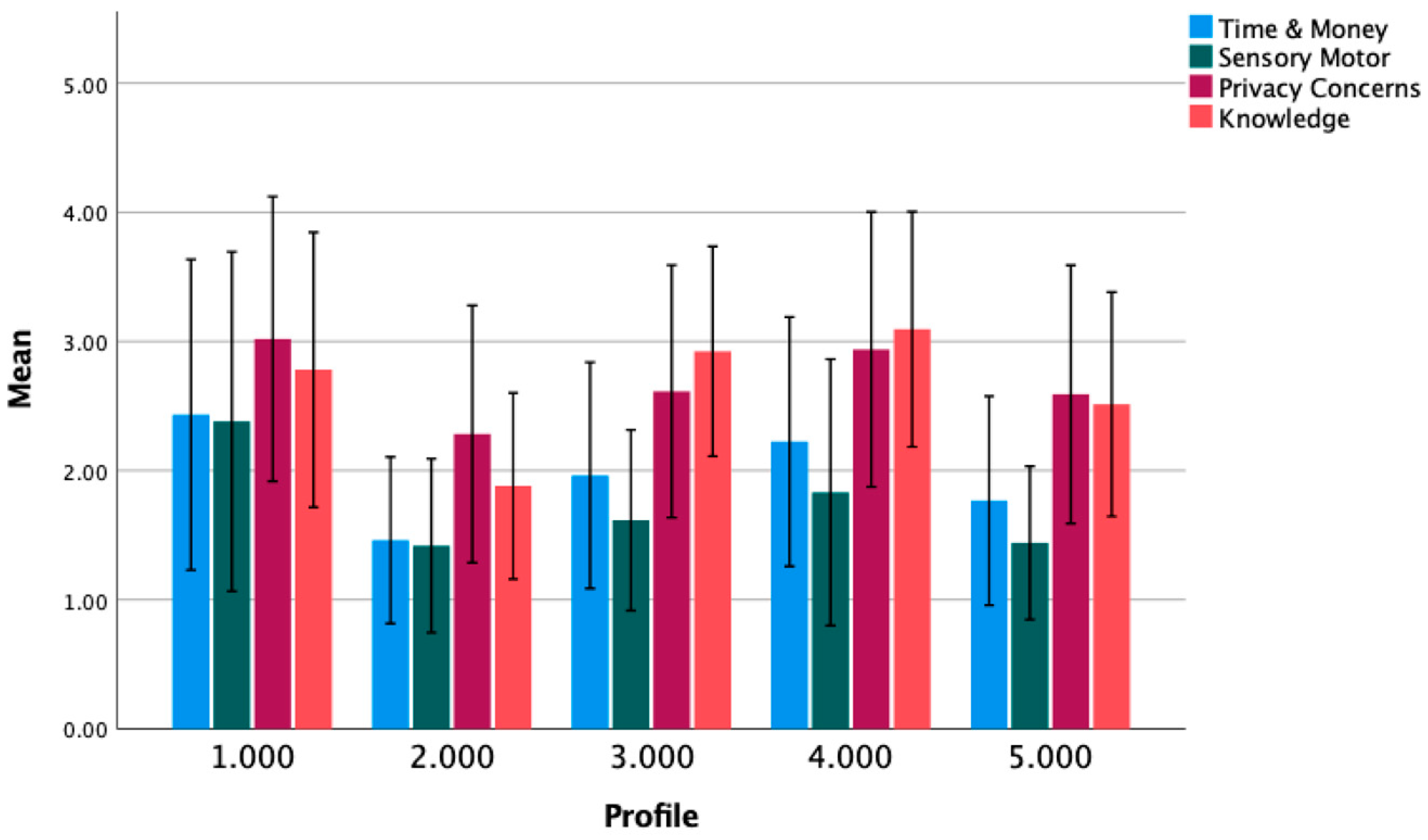

3.4. Technology Barriers

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Demographic Turning Points for the United States: Population Projections for 2020 to 2060 Population Estimates and Projections Current Population Reports. Available online: https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2020/demo/p25-1144.html (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Carstensen, L.L.; Isaacowitz, D.M.; Charles, S.T. Taking time seriously: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. Am. Psych. 1999, 54, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkley, L.C. Loneliness and health. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2022, 8, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sum, S.; Mathews, R.M.; Hughes, I.; Campbell, A. Internet use and loneliness in older adults. Cyberpsych. Behav. 2008, 11, 208–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, Q. The Effect of Social Media Use on Older Adults’ Loneliness-The Moderating Role of Self-Disclosure. In Proceedings of the Human Aspects of IT for the Aged Population. Technology and Society, 6th International Conference, ITAP 2020, Held as Part of the 22nd HCI International Conference, HCII 2020, Copenhagen, Denmark, 19–24 July 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deters, F.; Mehl, M.R. Does Posting Facebook Status Updates Increase or Decrease Loneliness? An Online Social Networking Experiment. Soc. Psych. Pers. Sci. 2013, 4, 579–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quan-Haase, A.; Young, A.L. Uses and Gratifications of Social Media: A Comparison of Facebook and Instant Messaging. Bull. Sci. Tech. Soc. 2010, 30, 350–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonsaksen, T.; Ruffolo, M.; Leung, J.; Price, D.; Thygesen, H.; Schoultz, M.; Geirdal, A.Ø. Loneliness and Its Association with Social Media Use During the COVID-19 Outbreak. Soc. Media Soc. 2021, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geirdal, A.Ø.; Ruffolo, M.; Leung, J.; Thygesen, H.; Price, D.; Bonsaksen, T.; Schoultz, M. Mental health, quality of life, wellbeing, loneliness and use of social media in a time of social distancing during the COVID-19 outbreak. A cross-country comparative study. J. Ment. Health 2021, 30, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muramatsu, K.; Fujino, Y.; Kubo, T.; Otani, M.; Matsuda, S. Relationship between treatment and period of absence among employees on sick leave due to mental disease. Ind. Health 2019, 57, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marttila, E.; Koivula, A.; Räsänen, P. Does excessive social media use decrease subjective well-being? A longitudinal analysis of the relationship between problematic use, loneliness and life satisfaction. Telemat. Inform. 2021, 59, 101556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretta, T.; Buodo, G. Problematic Internet Use and Loneliness: How Complex Is the Relationship? A Short Literature Review. Curr. Addict. Rep. 2020, 7, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, L.; Hallit, R.; Kheir, N.; Obeid, S.; Hallit, S. Social Media Use Disorder and Loneliness: Any Association Between the Two? Results of a Cross-Sectional Study Among Lebanese Adults. BMC Psychol. 2020, 8, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boursier, V.; Gioia, F.; Musetti, A.; Schimmenti, A. Facing Loneliness and Anxiety During the COVID-19 Isolation: The Role of Excessive Social Media Use in a Sample of Italian Adults. Front. Psych. 2020, 11, 586222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alheneidi, H.; AlSumait, L.; AlSumait, D.; Smith, A.P. Loneliness and Problematic Internet Use during COVID-19 Lock-Down. Behav. Sci. 2021, 11, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonsaksen, T.; Schoultz, M.; Thygesen, H.; Ruffolo, M.; Price, D.; Leung, J.; Geirdal, A.Ø. Loneliness and Its Associated Factors Nine Months after the COVID-19 Outbreak: A Cross-National Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halston, A.; Iwamoto, D.; Junker, M.; Chun, H. Social Media and Loneliness. Int. J. Psych. Stud. 2019, 11, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarts, S.; Peek, S.T.M.; Wouters, E.J.M. The relation between social network site usage and loneliness and mental health in community-dwelling older adults. Int. J. Geri. Psych. 2015, 30, 942–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, K.; Wu, S.; Chi, I. Internet Use and Loneliness of Older Adults Over Time: The Mediating Effect of Social Contact. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2021, 76, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumota, L.; Diniz, M.A.; Ribeiro, R.M.; Silva, I.L.; Figueira, A.L.; Rodrigues, F.R.; Rodrigues, R.A. Impact of digital social media on the perception of loneliness and social isolation in older adults. Rev. Lat. Am. Enferm. 2022, 30, e3573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolandi, E.; Vaccaro, R.; Abbondanza, S.; Casanova, G.; Pettinato, L.; Colombo, M.; Guaita, A. Loneliness and Social Engagement in Older Adults Based in Lombardy during the COVID-19 Lockdown: The Long-Term Effects of a Course on Social Networking Sites Use. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T. An exploratory analysis of the relationship of problematic Facebook use with loneliness and self-esteem: The mediating roles of extraversion and self-presentation. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, K.R.; Cosco, T.; Kervin, L.; Riadi, I.; O’Connell, M.E. Older Adults’ Experiences with Using Technology for Socialization During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Cross-sectional Survey Study. JMIR Aging 2021, 4, e28010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Chen, Y.; Hewitt, L. Age differences in constraints encountered by seniors in their use of computers and the internet. Comp. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leist, A.K. Social media use of older adults: A mini-review. Gerontology 2013, 59, 378–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, D.; Peplau, L.A.; Cutrona, C.E. The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: Concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. J. Person. Soc. Psych. 1980, 39, 472–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimrod, G. Technostress: Measuring a new threat to well-being in later life. Aging Ment. Health 2018, 22, 1080–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laganá, L.; Oliver, T.; Ainsworth, A.; Edwards, M. Enhancing computer self-efficacy and attitudes in multi-ethnic older adults: A randomized controlled study. Ageing Soc. 2011, 31, 911–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaportzis, E.; Clausen, M.G.; Gow, A.J. Older adults perceptions of technology and barriers to interacting with tablet computers: A focus group study. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User’s Guide, 6th ed.; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Beauchaine, T.P. Taxometrics and developmental psychopathology. Dev. Psychopathol. 2003, 15, 501–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nylund, K.L.; Asparouhov, T.; Muthén, B.O. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Struct. Equ. Model. 2007, 14, 535–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nylund, K.; Bellmore, A.; Nishina, A.; Graham, S. Subtypes, severity, and structural stability of peer victimization: What does latent class analysis say? Child Dev. 2007, 78, 1706–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akaike, H. Factor Analysis and AIC. Psychometrika 1987, 52, 317–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, G. Estimating the Dimension of a Model. Ann. Stat. 1978, 6, 461–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sclove, S.L. Application of model-selection criteria to some problems in multivariate analysis. Psychometrika 1987, 52, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaswamy, V.; Desarbo, W.S.; Reibstein, D.J.; Robinson, W.T. An Empirical Pooling Approach for Estimating Marketing Mix Elasticities with PIMS Data. Mark. Sci. 1993, 12, 103–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, M.B.; Kraut, R. Growing Closer on Facebook: Changes in Tie Strength Through Social Network Site Use. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Toronto, ON, Canada, 26 April 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phu, B.; Gow, A.J. Facebook use and its association with subjective happiness and loneliness. Comp. Human Behav. 2019, 92, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.C. Instagram Use, Loneliness, and Social Comparison Orientation: Interact and Browse on Social Media, but Don’t Compare. Cyberpsych. Behav. Soc. Net. 2016, 19, 703–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Demographic Characteristic | Mdn (Range) or % (n) |

|---|---|

| Age | 58 (30–97) |

| Sex (% women) | 61.2% (n = 569) |

| Education | --- |

| % High School Degree | 22.8% (n = 212) |

| % College Degree | 51.2% (n = 476) |

| % Graduate Degree | 25.9% (n = 241) |

| Annual Income | --- |

| <$35 K per year | 34.1% (n = 306) |

| $35–99 K per year | 43.1% (n = 387) |

| >$100 K per year | 22.8% (n = 205) |

| Race (% White) | 90.2% (n = 834) |

| Ethnicity (% Hispanic/Latino) | 2.9% (n = 27) |

| Indicator Variables | Mean (SD) |

| Social Media Use | 7.81 (6.04) |

| UCLA Loneliness | 38.21 (12.78) |

| Predictor Variables | Mean (SD) |

| Technology Barriers | 59.90 (20.15) |

| Knowledge | 25.86 (9.68) |

| Time and Money | 9.71 (4.87) |

| Sensory Motor | 5.16 (2.88) |

| Privacy Concerns | 10.68 (4.23) |

| # of Profiles | Free Parameters | AIC | BIC | ABIC | VLMRLRT p-Value | BLRT p-Value | Entropy | n of Smallest Group | % of Sample |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6 | 7903.97 | 7932.98 | 7913.92 | |||||

| 2 | 10 | 7630.48 | 7678.82 | 7647.06 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.80 | 448 | 0.48 |

| 3 | 14 | 7578.60 | 7646.28 | 7601.81 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.78 | 194 | 0.21 |

| 4 | 18 | 7517.02 | 7604.03 | 7546.87 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.77 | 93 | 0.10 |

| 5 | 22 | 7480.77 | 7587.12 | 7517.25 | 0.0318 | 0.0356 | 0.75 | 99 | 0.11 |

| 6 | 26 | 6149.66 | 6275.35 | 6192.78 | 0.0577 | 0.0627 | 0.93 | 42 | 0.05 |

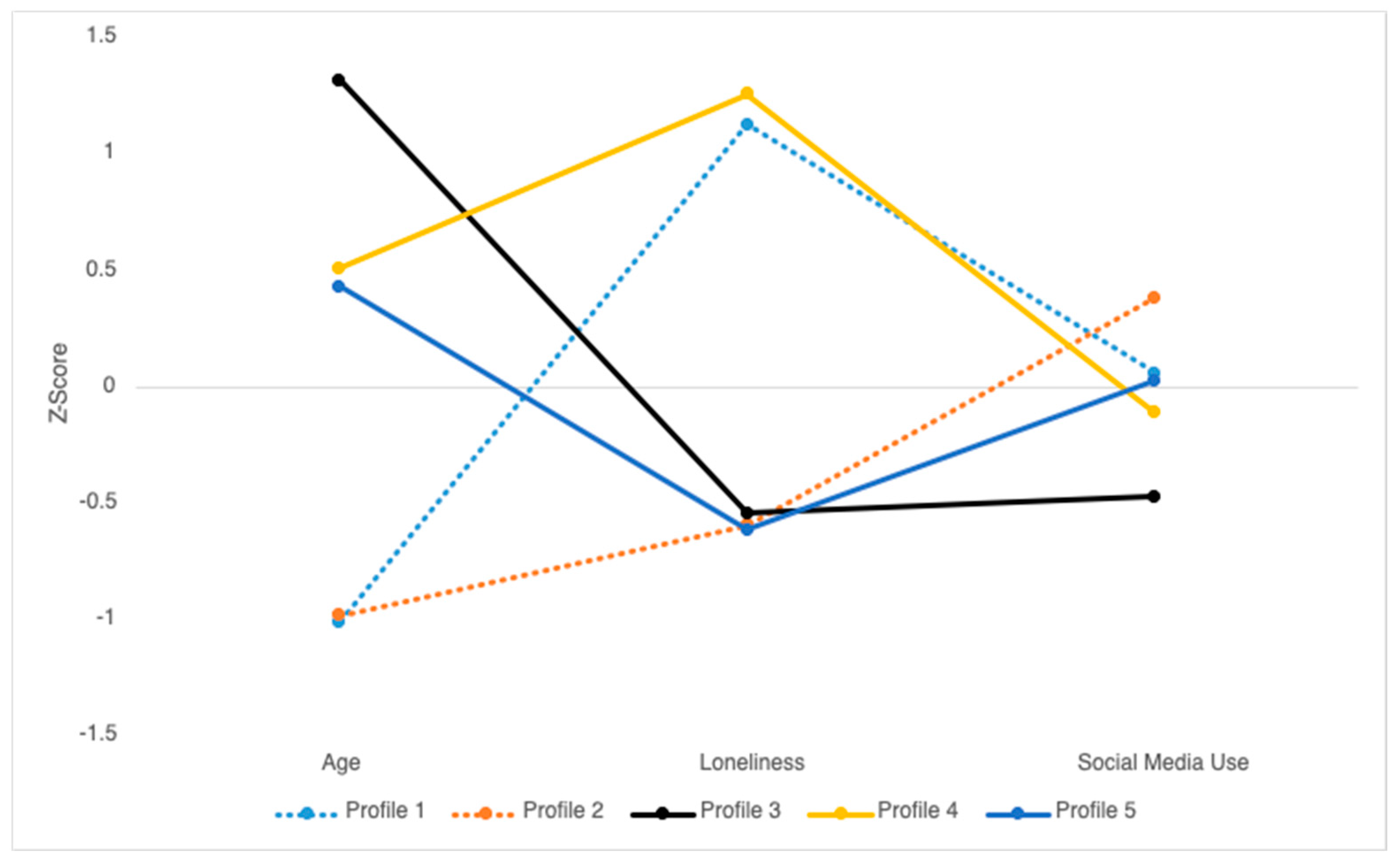

| Profile 1 (n = 210) | Profile 2 (n = 180) | Profile 3 (n = 164) | Profile 4 (n = 99) | Profile 5 (n = 276) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 39.69 (8.81) | 40.30 (5.84) | 82.24 (5.49) | 67.01 (7.78) | 64.44 (5.91) |

| Loneliness | 52.71 (7.49) | 30.69 (6.17) | 31.27 (7.44) | 54.33 (7.28) | 30.43 (7.17) |

| Social Media Use | 8.12 (5.90) | 10.42 (6.05) | 4.88 (5.55) | 6.92 (5.71) | 7.96 (5.74) |

| Characterization | Younger adults | Younger adults | Younger adults | Older adults | Middle-aged adults |

| Lonely | Not lonely | Not lonely | Lonely | Not lonely | |

| Average social media use | Frequent social media use | Infrequent social media use | Average social media use | Average social media use |

| Profile 1 | Profile 2 | Profile 3 | Profile 4 | Profile 5 | Omnibus Chi Square or Kruskal–Wallis | df | Effect Size/Cramer ’s V or Eta2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (% Woman) | 56 a | 56 a | 57 a | 66 a,b | 70 b | 16.125 * | 4 | 0.132 (medium) |

| Education | - | - | - | - | - | 30.684 * | 8 | 0.129 (medium) |

| % High School Degree | 23 a | 12 b | 30 a | 28 a | 24 a | - | - | - |

| % College Degree | 47 a | 53 a | 47 a | 56 a | 54 a | |||

| % Graduate Degree | 30.5 a,b | 35 b | 23 a,b | 16 a | 22 a | |||

| Income | - | - | - | - | - | 45.918 * | 8 | 0.160 (medium) |

| <$35 K per year [%] | 37.5 a,b | 23 c | 39 a,b | 52 b | 30 a,c | - | - | - |

| $35–99 K per year [%] | 33 a | 46 a,b | 44 a,b | 36 a,b | 51 b | - | - | - |

| >$100 K per year [%] | 30 a | 30.5 a | 17 a,b | 13 b | 19 a,b | - | - | - |

| Race (% White) | 80 a | 90 a,b | 97 b | 94 b | 93 b | 34.829 * | 4 | 0.194 (medium) |

| Ethnicity (% Hispanic/Latino) | 4 | 6 | 2.5 | 2 | 1 | 9.175 | 4 | 0.100 (small) |

| Technology Barriers M (SD) | 67.82 a (23.81) | 46.92 b (14.98) | 63.38 a (17.14) | 68.31 a (18.84) | 57.27 c (17.18) | 129.96 * | 4 | 0.136 (medium) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mckniff, M.; Simone, S.M.; Giovannetti, T. Age, Loneliness, and Social Media Use in Adults during COVID-19: A Latent Profile Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5969. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20115969

Mckniff M, Simone SM, Giovannetti T. Age, Loneliness, and Social Media Use in Adults during COVID-19: A Latent Profile Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(11):5969. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20115969

Chicago/Turabian StyleMckniff, Moira, Stephanie M. Simone, and Tania Giovannetti. 2023. "Age, Loneliness, and Social Media Use in Adults during COVID-19: A Latent Profile Analysis" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 11: 5969. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20115969

APA StyleMckniff, M., Simone, S. M., & Giovannetti, T. (2023). Age, Loneliness, and Social Media Use in Adults during COVID-19: A Latent Profile Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(11), 5969. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20115969