Reliability and Validity of the Japanese Version of the Short Form of the Expanded Version of the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI-X-SF-J): A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Demographics

2.3.2. Posttraumatic Growth

2.3.3. PTSD Symptoms

2.3.4. Stressful Events

2.3.5. Challenge to Core Beliefs

2.3.6. Ruminative Process

2.4. Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ Demographics

3.2. Scores of the Scales

3.3. Exploratory Factor Analysis

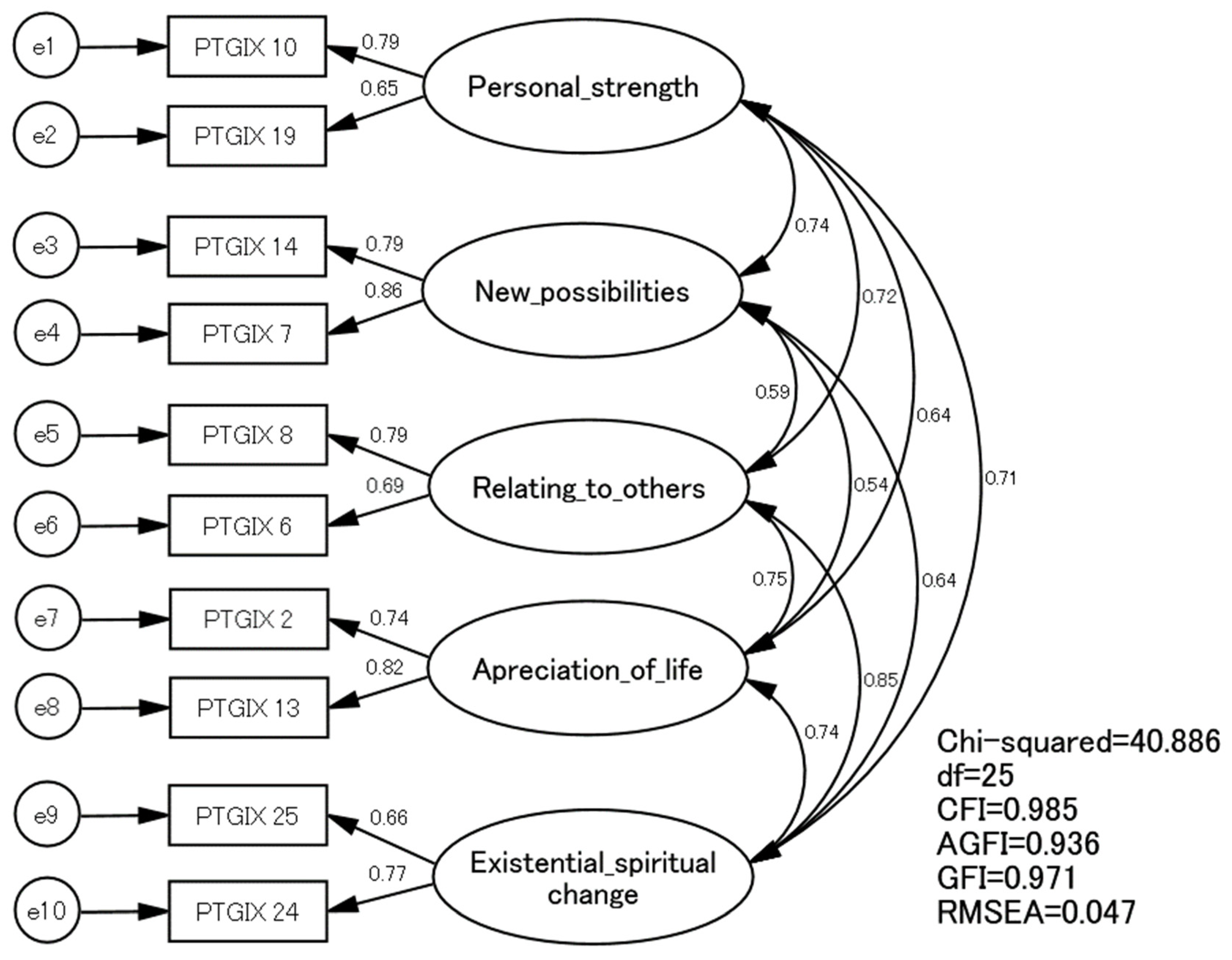

3.4. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

3.5. Reliability

3.6. Validity

4. Discussion

4.1. Clinical Implications

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Calhoun, L.G.; Tedeschi, R.G. (Eds.) Facilitating Posttraumatic Growth: A Clinician’s Guide, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Casellas-Grau, A.; Vives, J.; Font, A.; Ochoa, C. Positive psychological functioning in breast cancer: An integrative review. Breast 2016, 27, 136–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hefferon, K.; Grealy, M.; Mutrie, N. Post-traumatic growth and life threatening physical illness: A systematic review of the qualitative literature. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2009, 14, 343–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyerson, D.A.; Grant, K.E.; Carter, J.S.; Kilmer, R.P. Posttraumatic growth among children and adolescents: A systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 31, 949–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michael, C.; Cooper, M. Post-traumatic growth following bereavement: A systematic review of the literature. Couns. Psychol. Rev. 2013, 28, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picoraro, J.A.; Womer, J.W.; Kazak, A.E.; Feudtner, C. Posttraumatic growth in parents and pediatric patients. J. Palliat. Med. 2014, 17, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulloa, E.; Guzman, M.L.; Salazar, M.; Cala, C. Posttraumatic growth and sexual violence: A literature review. J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma. 2016, 25, 286–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, M.; Lowe, M.; Graham-Kevan, N.; Robinson, S. Posttraumatic growth in students, crime survivors and trauma workers exposed to adversity. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2016, 98, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, R.G.; Calhoun, L.G. The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. J. Trauma. Stress. 1996, 9, 455–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, L.M.; Marotta, S.A.; Depuy, V. A confirmatory factor analytic study of the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory among a sample of racially diverse college students. J. Ment. Health 2009, 18, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigemoto, Y.; Poyrazli, S. Factors related to posttraumatic growth in U.S. and Japanese college students. Psychol. Trauma. Res. Pract. Policy 2013, 5, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taku, K.; Calhoun, L.G.; Tedeschi, R.G.; Gil-Rivas, V.; Kilmer, R.P.; Cann, A. Examining posttraumatic growth among Japanese university students. Anxiety Stress Coping 2007, 20, 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedeschi, R.G.; Cann, A.; Taku, K.; Senol-Durak, E.; Calhoun, L.G. The posttraumatic growth inventory: A revision integrating existential and spiritual change. J. Trauma. Stress 2017, 30, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedeschi, R.G.; Shakespeare-Finch, J.; Taku, K.; Calhoun, L.G. Posttraumatic Growth: Theory, Research, and Applications; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Taku, K.; Cann, A.; Tedeschi, R.G.; Calhoun, L.G. Core beliefs shaken by an earthquake correlate with posttraumatic growth. Psychol. Trauma. 2015, 7, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cann, A.; Calhoun, L.G.; Tedeschi, R.G.; Taku, K.; Vishnevsky, T.; Triplett, K.N.; Danhauer, S.C. A short form of the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory. Anxiety Stress Coping 2010, 23, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cann, A.; Calhoun, L.G.; Tedeschi, R.G.; Triplett, K.N.; Vishnevsky, T.; Lindstrom, C.M. Assessing posttraumatic cognitive processes: The Event Related Rumination Inventory. Anxiety Stress Coping 2011, 24, 137–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, R.G.; Calhoun, L.G. Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychol. Inq. 2004, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.N.; Wang, L.L.; Li, H.P.; Gong, J.; Liu, X.H. Correlation between posttraumatic growth and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms based on Pearson correlation coefficient: A meta-analysis. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2017, 205, 380–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Xu, J.; Sui, Y. Posttraumatic stress disorder and posttraumatic growth coexistence and the risk factors in Wenchuan earthquake survivors. Psychiatry Res. 2016, 237, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Ying, L.; Zhou, X.; Wu, X.; Lin, C. The effects of extraversion, social support on the posttraumatic stress disorder and posttraumatic growth of adolescent survivors of the Wenchuan earthquake. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0121480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wu, X.; Zhen, R. Understanding the relationship between social support and posttraumatic stress disorder/posttraumatic growth among adolescents after Ya’an earthquake: The role of emotion regulation. Psychol. Trauma. 2017, 9, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Peng, L.; Chen, L.; Long, L.; He, W.; Li, M.; Wang, T. Resilience and social support promote posttraumatic growth of women with infertility: The mediating role of positive coping. Psychiatry Res. 2014, 215, 401–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, J.; Newton, J.; Copnell, B. Posttraumatic growth experiences and its contextual factors in women with breast cancer: An integrative review. Health Care Women Int. 2019, 40, 554–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husson, O.; Zebrack, B.; Block, R.; Embry, L.; Aguilar, C.; Hayes-Lattin, B.; Cole, S. Posttraumatic growth and well-being among adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with cancer: A longitudinal study. Support. Care Cancer 2017, 25, 2881–2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangeri, L.; Scrignaro, M.; Bianchi, E.; Borreani, C.; Bhoorie, S.; Mazzaferro, V. A longitudinal investigation of posttraumatic growth and quality of life in liver transplant recipients. Prog. Transplant. 2018, 28, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martz, E.; Livneh, H.; Southwick, S.M.; Pietrzak, R.H. Posttraumatic growth moderates the effect of posttraumatic stress on quality of life in U.S. military veterans with life-threatening illness or injury. J. Psychosom. Res. 2018, 109, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cann, A.; Calhoun, L.G.; Tedeschi, R.G.; Kilmer, R.P.; Gil-Rivas, V.; Vishnevsky, T.; Danhauer, S.C. The Core Beliefs Inventory: A brief measure of disruption in the assumptive world. Anxiety Stress Coping 2010, 23, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, M.C.; Delgado, J.B.; Alvarado, E.R.; Rovira, D.P. Spanish adaptation and validation of the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory–Short Form. Violence Vict. 2015, 30, 756–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, F.E.; Wlodarczyk, A. Psychometric properties of the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory–short form among Chilean adults. J. Loss Trauma. 2016, 21, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamela, D.; Figueiredo, B.; Bastos, A.; Martins, H. Psychometric properties of the Portuguese version of the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory Short Form among divorced adults. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2014, 30, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, H.; Kobayashi, N.; Honda, N.; Matsuoka, H.; Yamaguchi, T.; Homma, H.; Tomita, H. Post-traumatic growth of children affected by the Great East Japan Earthquake and their attitudes to memorial services and media coverage. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2016, 70, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taku, K. Commonly defined and individually defined posttraumatic growth in the US and Japan. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2011, 51, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshiro, R.; Kopitz, J.; Soejima, T.; Kibi, S.; Kamibeppu, K.; Sakamoto, S.; Taku, K. Perceptions of positive and negative changes for posttraumatic growth and depreciation: Judgments from Japanese undergraduates. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2019, 137, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taku, K.; Tedeschi, R.G.; Shakespeare-Finch, J.; Krosch, D.; David, G.; Kehl, D.; Grunwald, S.; Romeo, A.; Di Tella, M.; Kamibeppu, K.; et al. Posttraumatic growth (PTG) and posttraumatic depreciation (PTD) across ten countries: Global validation of the PTG-PTD theoretical model. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2021, 169, 110222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, M.; Takebayashi, Y.; Suzuki, Y.; Horikoshi, M. Corrigendum to “Posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5: Psychometric properties in a Japanese population.”. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 247, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weathers, F.W.; Litz, B.T.; Keane, T.M.; Palmieri, P.A.; Marx, B.P.; Schnurr, P.P. The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). Scale Available from the National Center for PTSD. 2013. Available online: http://www.ptsd.va.go (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Schermelleh-Engel, K.; Moosbrugger, H.; Müller, H. Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods Psychol. Res. 2003, 8, 23–74. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Science; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Platte, S.; Wiesmann, U.; Tedeschi, R.G.; Taku, K.; Kehl, D. A short form of the posttraumatic growth and posttraumatic depreciation inventory—Expanded (PTGDI-X-SF) among German adults. Psychol. Trauma. Res. Pract. Policy 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, F.; Nikaido, K. Religious faith and religious feelings in Japan: Analyses of cross-cultural and longitudinal surveys. Behaviormetrika 2009, 36, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manabe, K. The structure of Japanese religiosity. Kansei Gakuin Univ. Sch. Sociol. J. 2008, 104, 45–70. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Danhauer, S.C.; Russell, G.B.; Tedeschi, R.G.; Jesse, M.T.; Vishnevsky, T.; Daley, K.; Carroll, S.; Triplett, K.N.; Calhoun, L.G.; Cann, A.; et al. A longitudinal investigation of posttraumatic growth in adult patients undergoing treatment for acute leukemia. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2013, 20, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irie, W.; Shiwaku, H.; Taku, K.; Suzuki, Y.; Inoue, Y. Roles of reexamination of core beliefs and rumination in posttraumatic growth among parents of children with cancer: Comparisons with parents of children with chronic disease. Cancer Nurs. 2021, 44, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindstrom, C.M.; Cann, A.; Calhoun, L.G.; Tedeschi, R.G. The relationship of core belief challenge, rumination, disclosure, and sociocultural elements to posttraumatic growth. Psychol. Trauma. Res. Pract. Policy 2013, 5, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigemoto, Y.; Low, B.; Borowa, D.; Robitschek, C. Function of personal growth initiative on posttraumatic growth, posttraumatic stress, and depression over and above adaptive and maladaptive rumination. J. Clin. Psychol. 2017, 73, 1126–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, L.D.; Blasey, C.M.; Garlan, R.W.; McCaslin, S.E.; Azarow, J.; Chen, X.H.; Des Desjardins, J.C.; DiMiceli, S.; Seagraves, D.A.; Hastings, T.A.; et al. Posttraumatic growth following the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001: Cognitive, coping, and trauma symptom predictors in an internet convenience sample. Traumatology 2005, 11, 247–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zebrack, B.; Kwak, M.; Salsman, J.; Cousino, M.; Meeske, K.; Aguilar, C.; Embry, L.; Block, R.; Hayes-Lattin, B.; Cole, S. The relationship between posttraumatic stress and posttraumatic growth among adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology 2015, 24, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auerbach, R.P.; Mortier, P.; Bruffaerts, R.; Alonso, J.; Benjet, C.; Cuijpers, P.; Demyttenaere, K.; Ebert, D.D.; Green, J.G.; Hasking, P.; et al. WHO World Mental Health Surveys International College Student Project: Prevalence and distribution of mental disorders. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2018, 127, 623–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornblith, A.B.; Regan, M.M.; Kim, Y.; Greer, G.; Parker, B.; Bennett, S.; Winer, E. Cancer-related communication between female patients and male partners scale: A pilot study. Psycho-Oncology 2006, 15, 780–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| First Sample | Second Sample | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 408) | (n = 284) | |||

| Mean ± SD a or n (%) | ||||

| Age (years) | 22.2 | ±7.3 | 21.2 | ±7.3 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 152 | (37.3) | 96 | (33.8) |

| Female | 255 | (62.5) | 185 | (65.1) |

| Other | 1 | (0.2) | 3 | (1.1) |

| Nationality | ||||

| Japan | 391 | (95.8) | 281 | (98.9) |

| Other | 17 | (4.2) | 3 | (1.1) |

| Religion | ||||

| Non-religious | 279 | (68.7) | - | |

| Buddhism | 95 | (23.4) | - | |

| Christianity | 8 | (2.0) | - | |

| Shintoism | 7 | (1.7) | - | |

| Other | 17 | (4.2) | - | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 21 | (5.1) | 2 | (0.7) |

| Single | 384 | (94.1) | 282 | (99.3) |

| Other | 3 | (0.7) | 2 | (0.7) |

| PTGI-X-J total b | 46.0 | ±24.6 | 44.8 | ±27.2 |

| Personal strength | 7.7 | ±5.6 | 7.1 | ±5.3 |

| New possibilities | 11.4 | ±7.1 | 9.5 | ±6.8 |

| Relating to others | 14.0 | ±8.6 | 13.8 | ±8.8 |

| Appreciation of life | 6.4 | ±3.9 | 6.7 | ±4.0 |

| Existential/spiritual change | 6.8 | ±6.0 | 7.8 | ±6.8 |

| PCL-5 c | - | 16.3 | ±17.4 | |

| The stress level of the event at the time d | 6.0 | ±1.1 | 4.0 | ±1.0 |

| CBI e | - | 2.5 | ±1.2 | |

| ERRI-Intrusive f | - | 2.2 | ±1.2 | |

| ERRI-Deliberate f | - | 1.9 | ±1.0 | |

| Items | Factor a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| No. 10 | I know better I can handle difficulties | 0.794 | 0.235 | 0.201 | 0.153 | 0.041 |

| No. 19 | I discovered that I’m stronger than I thought I was | 0.696 | 0.135 | 0.090 | 0.142 | 0.104 |

| No. 4 | I have a greater feeling of self-reliance | 0.646 | 0.269 | 0.150 | 0.122 | 0.245 |

| No. 11 | I am able to do better things with my life | 0.571 | 0.491 | 0.306 | 0.131 | 0.128 |

| No. 12 | I am better able to accept the way things work out | 0.543 | 0.314 | 0.181 | 0.113 | 0.066 |

| No. 14 | New opportunities are available which wouldn’t have been otherwise | 0.316 | 0.698 | 0.093 | −0.083 | 0.115 |

| No. 7 | I established a new path for my life | 0.374 | 0.686 | 0.187 | 0.023 | 0.179 |

| No. 17 | I am more likely to try to change things, which need changing | 0.258 | 0.590 | 0.257 | 0.128 | 0.128 |

| No. 3 | I developed new interests | 0.221 | 0.523 | 0.245 | 0.132 | 0.197 |

| No. 1 | I changed my priorities about what is important in life | 0.147 | 0.357 | 0.177 | 0.265 | 0.111 |

| No. 8 | I have a greater sense of closeness with others | 0.235 | 0.041 | 0.753 | 0.090 | 0.087 |

| No. 6 | I more clearly see that I can count on people in times of trouble | 0.182 | 0.120 | 0.676 | 0.083 | 0.078 |

| No. 21 | I better accept needing others | 0.089 | 0.242 | 0.661 | 0.206 | 0.081 |

| No. 16 | I put more effort into my relationships | 0.049 | 0.389 | 0.559 | 0.219 | −0.058 |

| No. 9 | I am more willing to express my emotions | 0.307 | 0.155 | 0.552 | 0.079 | 0.265 |

| No. 15 | I have more compassion for others | −0.027 | 0.406 | 0.520 | 0.401 | −0.088 |

| No. 23 | I feel better able to face questions about life and death | 0.018 | −0.060 | 0.133 | 0.813 | 0.009 |

| No. 2 | I have a greater appreciation for the value of my own life | 0.093 | −0.112 | 0.162 | 0.753 | 0.114 |

| No. 13 | I can better appreciate each day | 0.195 | 0.291 | 0.304 | 0.541 | 0.104 |

| No. 20 | I learned a great deal about how wonderful people are | 0.200 | 0.173 | 0.228 | 0.504 | 0.294 |

| No. 22 | I have greater clarity about life’s meaning | 0.171 | 0.241 | 0.245 | 0.491 | 0.230 |

| No. 5 | I have a better understanding of spiritual matters | 0.197 | 0.235 | 0.003 | 0.459 | 0.363 |

| No. 18 | I have a stronger religious faith | 0.102 | 0.138 | −0.065 | 0.344 | 0.295 |

| No. 24 | I feel more connected with all of existence | 0.155 | 0.245 | 0.194 | 0.158 | 0.639 |

| No. 25 | I have a greater sense of harmony with the world | 0.244 | 0.299 | 0.084 | 0.454 | 0.491 |

| χ2/df | CFI c | AGFI d | GFI e | RMSEA f | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 a | 3.15 | 0.951 | 0.887 | 0.949 | 0.087 |

| Model 2 b | 1.64 | 0.985 | 0.936 | 0.971 | 0.047 |

| PCL-5 c | CBI d | ERRI-I e | ERRI-D e | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTGI-X-J a | ||||

| Total | 0.058 | 0.360 ** | 0.176 ** | 0.456 ** |

| Factor 1 | 0.023 | 0.239 ** | 0.045 | 0.342 ** |

| Factor 2 | 0.059 | 0.404 ** | 0.192 ** | 0.507 ** |

| Factor 3 | 0.059 | 0.273 * | 0.211 * | 0.407 ** |

| Factor 4 | −0.050 | 0.212 ** | 0.070 | 0.281 ** |

| Factor 5 | 0.126 * | 0.375 ** | 0.151 * | 0.509 ** |

| PTGI-X-SF-J b | ||||

| Total | −0.027 | 0.249 ** | 0.086 | 0.369 ** |

| Factor 1 | −0.003 | 0.200 ** | 0.057 | 0.340 ** |

| Factor 2 | −0.005 | 0.372 ** | 0.163 ** | 0.432 ** |

| Factor 3 | −0.016 | 0.124 * | 0.128 * | 0.253 ** |

| Factor 4 | −0.083 | 0.081 | −0.027 | 0.187 ** |

| Factor 5 | 0.068 | 0.251 ** | 0.036 | 0.269 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oshiro, R.; Soejima, T.; Kita, S.; Benson, K.; Kibi, S.; Hiraki, K.; Kamibeppu, K.; Taku, K. Reliability and Validity of the Japanese Version of the Short Form of the Expanded Version of the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI-X-SF-J): A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5965. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20115965

Oshiro R, Soejima T, Kita S, Benson K, Kibi S, Hiraki K, Kamibeppu K, Taku K. Reliability and Validity of the Japanese Version of the Short Form of the Expanded Version of the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI-X-SF-J): A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(11):5965. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20115965

Chicago/Turabian StyleOshiro, Rei, Takafumi Soejima, Sachiko Kita, Kayla Benson, Satoshi Kibi, Koichi Hiraki, Kiyoko Kamibeppu, and Kanako Taku. 2023. "Reliability and Validity of the Japanese Version of the Short Form of the Expanded Version of the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI-X-SF-J): A Cross-Sectional Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 11: 5965. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20115965

APA StyleOshiro, R., Soejima, T., Kita, S., Benson, K., Kibi, S., Hiraki, K., Kamibeppu, K., & Taku, K. (2023). Reliability and Validity of the Japanese Version of the Short Form of the Expanded Version of the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI-X-SF-J): A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(11), 5965. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20115965