Diabetic Foot Assessment and Care: Barriers and Facilitators in a Cross-Sectional Study in Bangalore, India

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Study Population

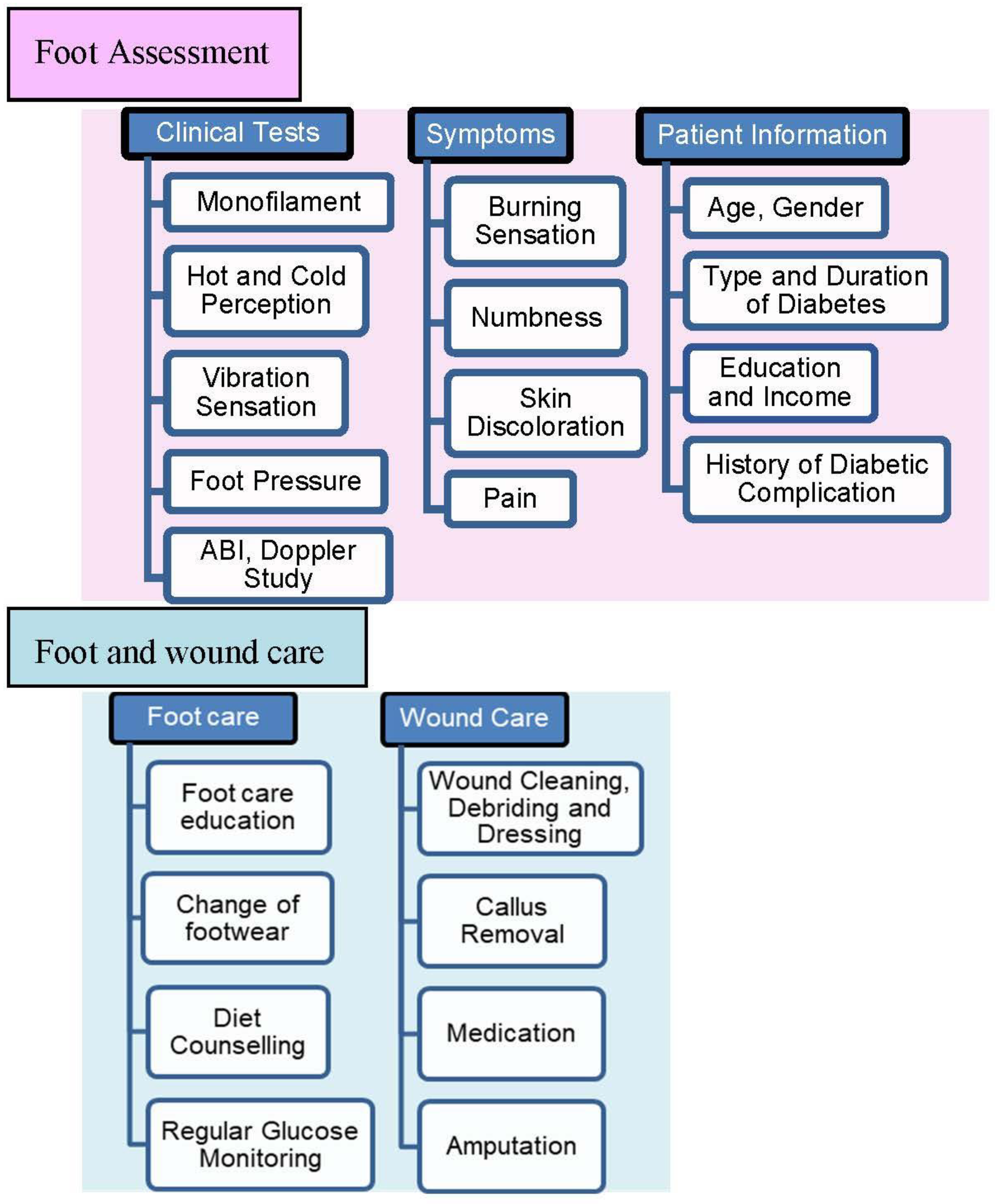

2.3. Clinical Foot Assessment and Foot Care Management Practices

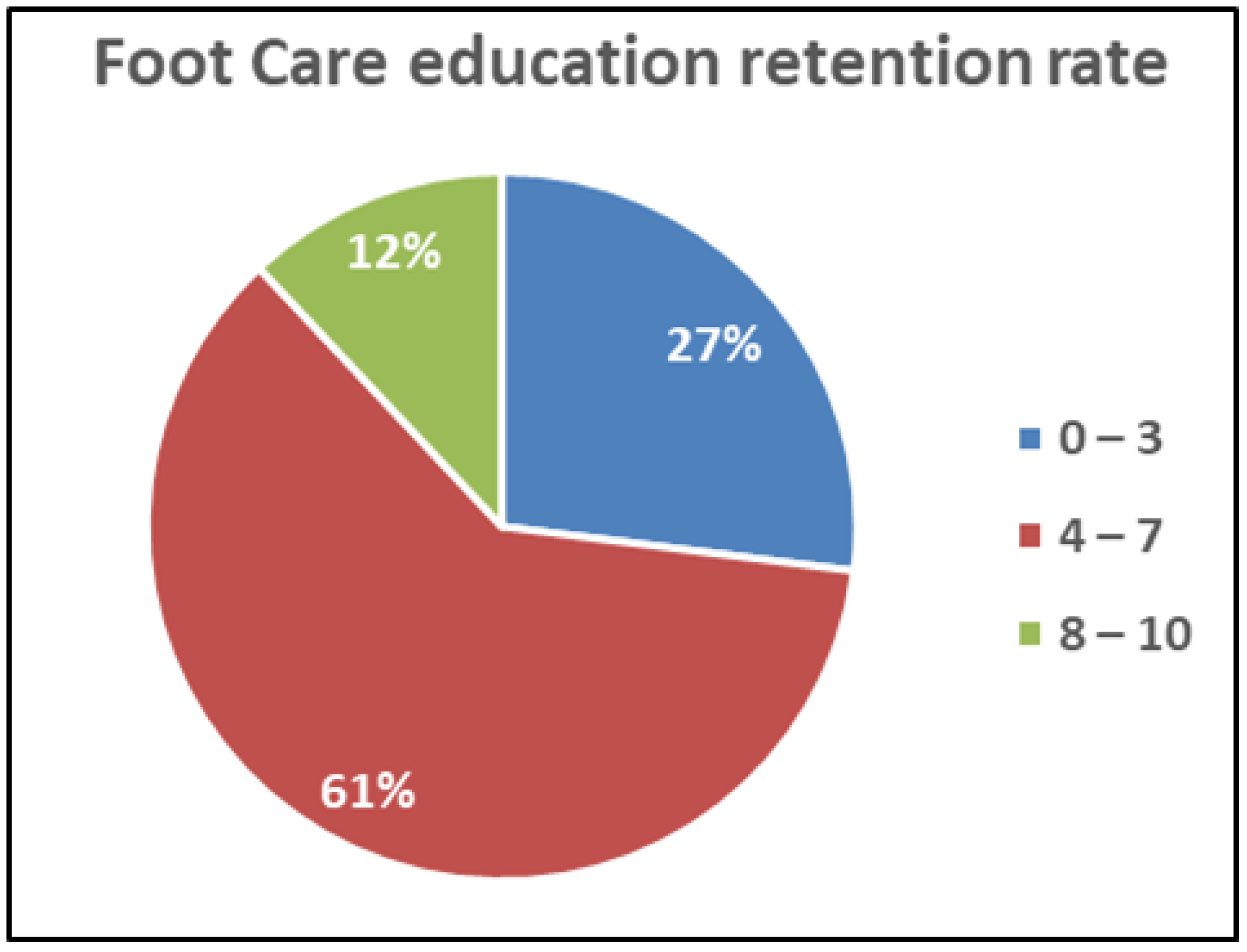

2.4. Foot Care Education Retention Rate

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics of Patients

3.2. Statistical Test Results

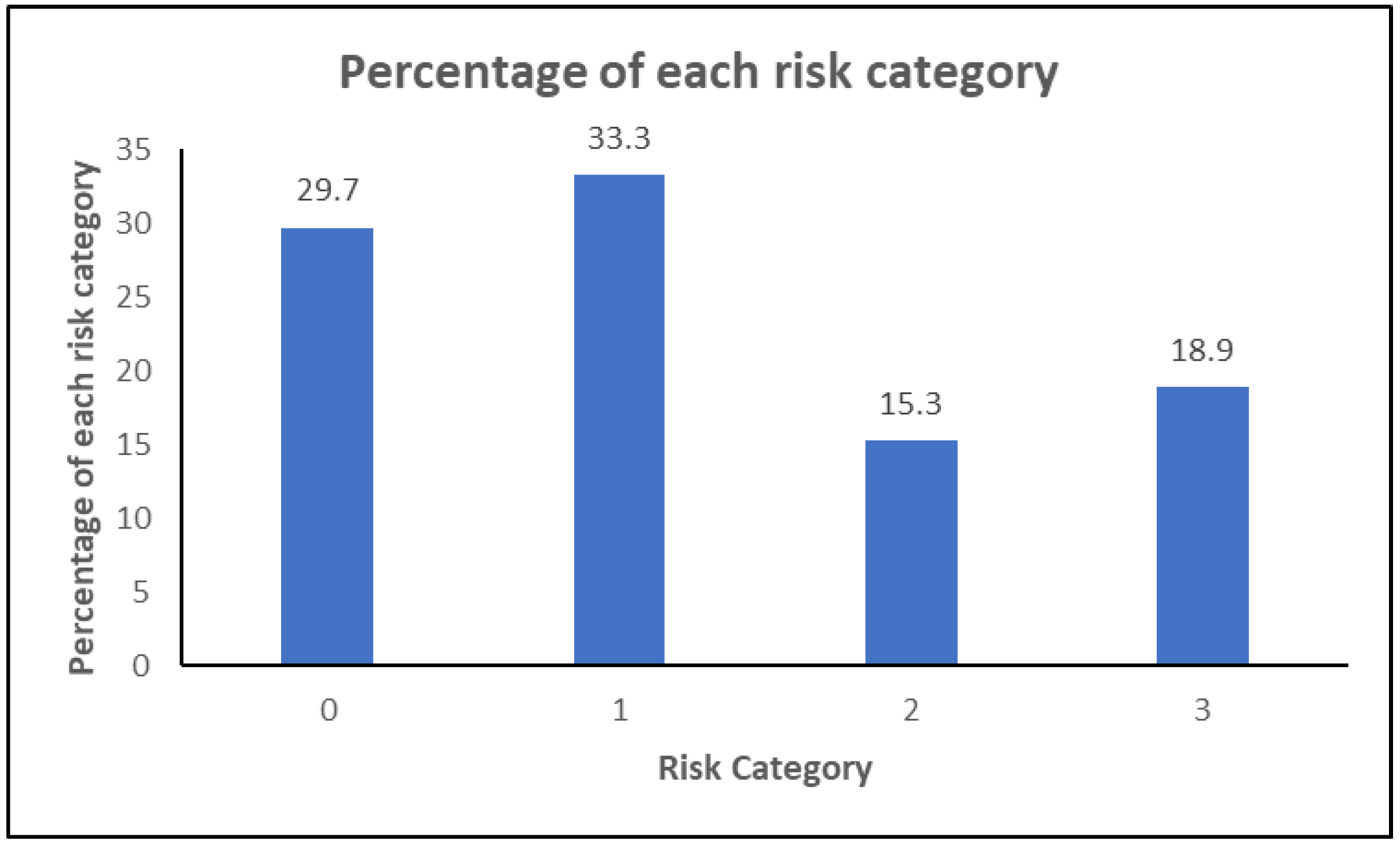

3.3. Risk Classification of Patients

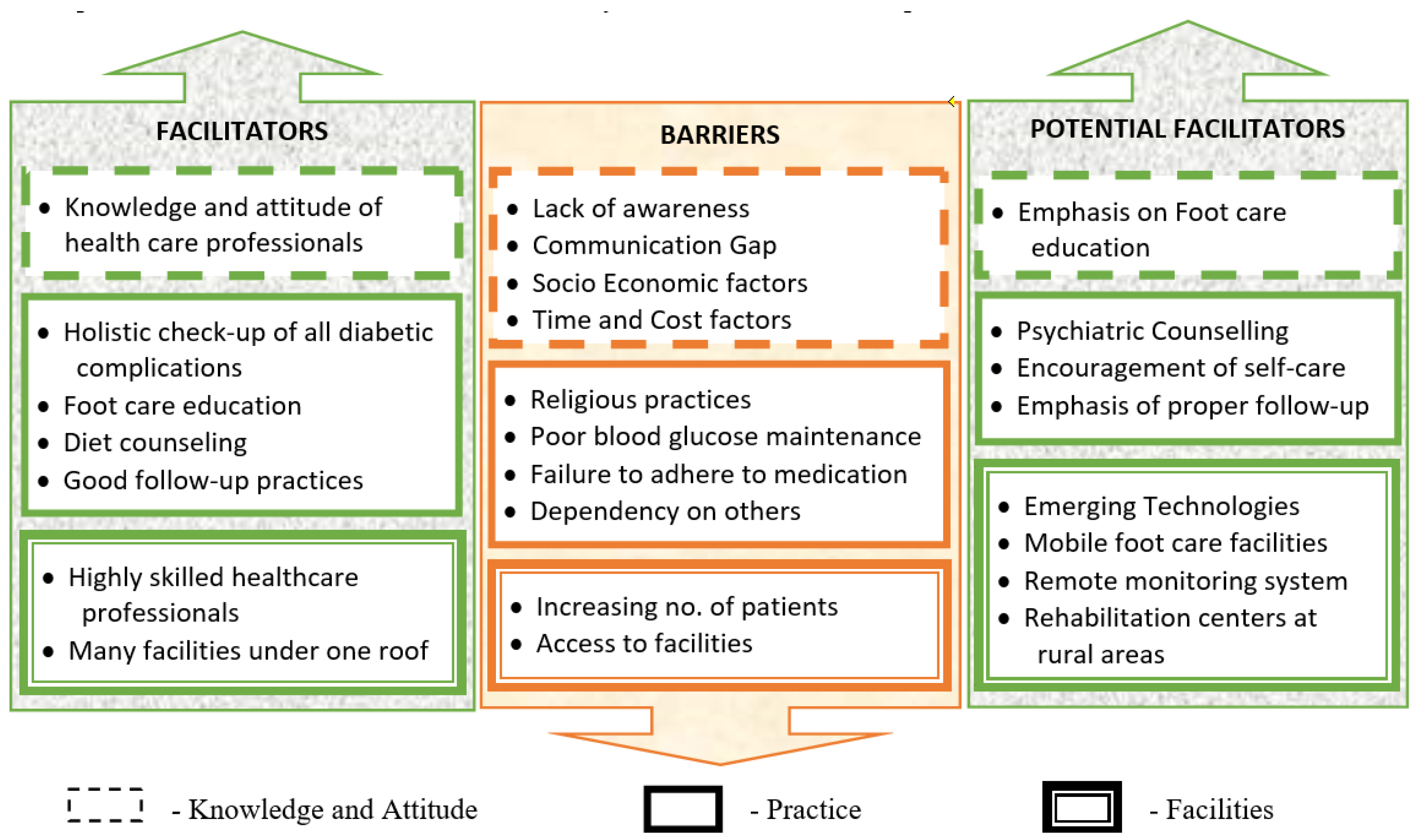

3.4. Barriers and Facilitators

3.4.1. Barriers

Lack of Awareness

Religious Practices

Time and Cost Factor

Socio-Economic Factor

Working Environment Factor

Access to Specialized Foot Care and Increasing Number of Patients

Dependency by the Patient

Communication Gap

Poor Blood Glucose Level Monitoring

3.4.2. Facilitators

3.4.3. Potential Facilitators

3.5. Strength and Limitations of the Study

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 10th ed.; IDF: Brussels, Belgium, 2021; Available online: https://www.diabetesatlas.org (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Word Diabetes Day (WDD). Available online: https://worlddiabetesday.org/about/theme/ (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Ghosh, P.; Valia, R. Burden of Diabetic Foot Ulcers in India: Evidence Landscape from Published Literature. Value Health 2017, 20, A485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, D.G.; Wrobel, J.; Robbins, J.M. Guest editorial-are diabetes-related wounds and amputation worse than cancer? Int. Wound J. 2007, 4, 286–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N.; Armstrong, D.G.; Lipsky, B.A. Preventing foot ulcers in patients with diabetes. JAMA 2005, 293, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiber, G.E. Epidemiology of Foot Ulcers and Amputations in the Diabetic Foot. In Levin and O’Neal’s the Diabetic Foot, 6th ed.; Bowker, J.H., Pfeifer, M.A., Eds.; Mosby: St Louis, MO, USA, 2001; pp. 13–32. [Google Scholar]

- Akila, M.; Ramesh, R.S.; Kumari, M.J. Assessment of diabetic foot risk among diabetic patients in a tertiary care hospital, South India. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2021, 10, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apelqvist, J.; Bakker, K.; van Houtum, W.H.; Schaper, N.C. Practical guidelines on the management and prevention of the diabetic foot. Diabetes/Metab. Res. Rev. 2008, 24 (Suppl. S1), S181–S187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, K.; Apelqvist, J.; Schaper, N.C.; International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot Editorial Board. Practical guidelines on the management and prevention of the diabetic foot 2011. Diabetes/Metab. Res. Rev. 2012, 28 (Suppl. S1), 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot (IWGDF). Available online: https://iwgdfguidelines.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/IWGDF-Guidelines-2019.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Zhang, P.; Lu, J.; Jing, Y.; Tang, S.; Zhu, D.; Bi, Y. Global epidemiology of diabetic foot ulceration: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Med. 2017, 49, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vibha, S.P.; Kulkarni, M.M.; Ballala, A.B.K.; Kamath, A.; Maiya, G.A. Community based study to assess the prevalence of diabetic foot syndrome and associated risk factors among people with diabetes mellitus. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2018, 18, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guell, C.; Unwin, N. Barriers to diabetic foot care in a developing country with a high incidence of diabetes related amputations: An exploratory qualitative interview study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015, 15, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Recommendations for the Conduct, Reporting, Editing, and Publication of Scholarly Work in Medical Journals. 2018. Available online: https://www.icmje.org/icmje-recommendations.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2023).

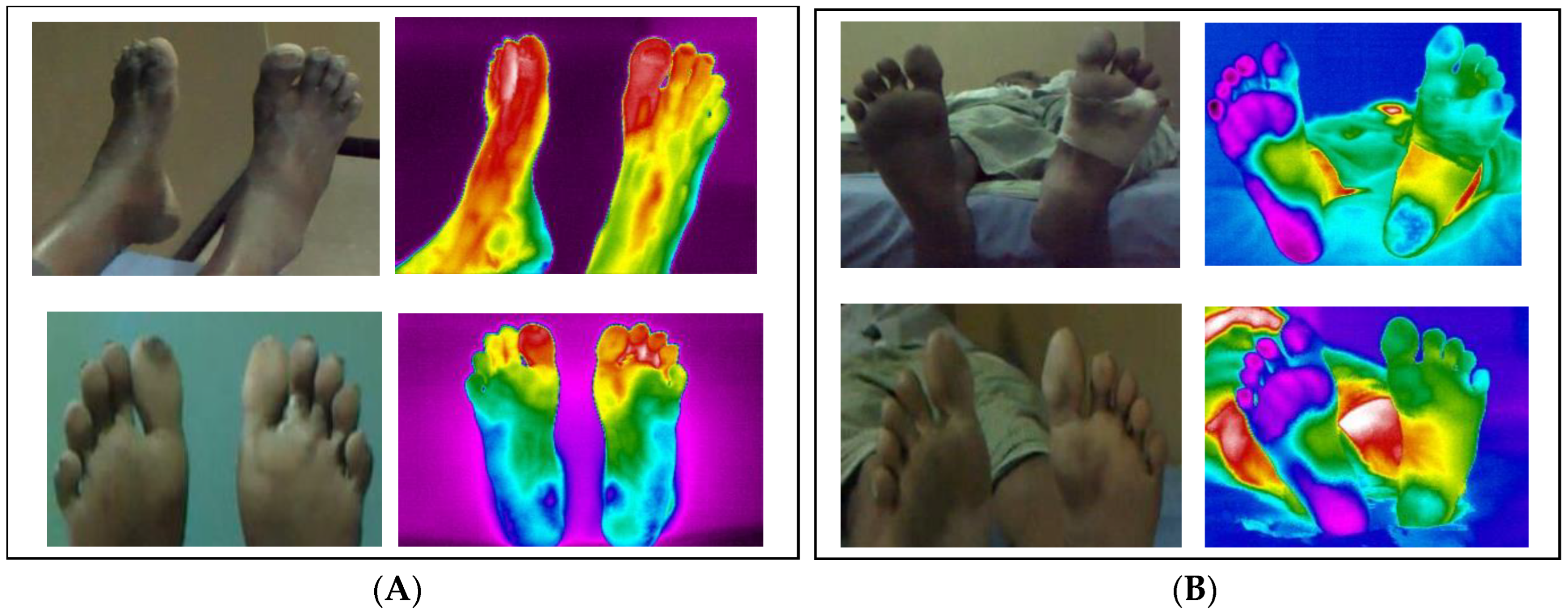

- Sudha, B.G.; Umadevi, V.; Shivaram, J.M.; Sikkandar, M.Y.; Al Amoudi, A.; Chaluvanarayana, H.C. Statistical Analysis of Surface Temperature Distribution Pattern in Plantar Foot of Healthy and Diabetic Subjects Using Thermography. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Communication and Signal Processing (ICCSP), Chennai, India, 3–5 April 2018; pp. 0219–0223. [Google Scholar]

- Gururajarao, S.B.; Venkatappa, U.; Shivaram, J.M.; Sikkandar, M.Y.; Al Amoudi, A. Infrared Thermography and Soft Computing for Diabetic Foot Assessment. In Machine Learning in Bio-Signal Analysis and Diagnostic Imaging; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 73–97. [Google Scholar]

- Abraham, S.; Jyothylekshmy, V.; Menon, A.S. Epidemiology of diabetic foot complications in a podiatry clinic of a tertiary hospital in South India. Indian J. Health Sci. Biomed. Res. 2015, 8, 48–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, V. The Diabetic Foot: Perspectives from Chennai, South India. Int. J. Low. Extrem. Wounds 2007, 6, 34–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulton, A.J.; Armstrong, D.G.; Albert, S.F.; Frykberg, R.G.; Hellman, R.; Kirkman, M.S.; Lavery, L.A.; LeMaster, J.W.; Mills, J.L.; Mueller, M.J.; et al. Comprehensive foot examination and risk assessment: A report of the task force of the foot care interest group of the American Diabetes Association, with endorsement by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. Diabetes Care 2008, 31, 1679–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Diabetes Federation E-library. IDF Clinical Practice Recommendations on the Diabetic Foot 2017. Available online: https://www.idf.org/e-library/guidelines/119-idf-clinical-practice-recommendations-on-diabetic-foot-2017.html (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Chellan, G.; Srikumar, S.; Varma, A.K.; Mangalanandan, T.; Sundaram, K.; Jayakumar, R.; Bal, A.; Kumar, H. Foot care practice—The key to prevent diabetic foot ulcers in India. Foot 2012, 22, 298–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gagliardino, J.J.; Chantelot, J.-M.; Domenger, C.; Ilkova, H.; Ramachandran, A.; Kaddaha, G.; Mbanya, J.C.; Chan, J.; Aschner, P.; IDMPS Steering Committee. Diabetes education and health insurance: How they affect the quality of care provided to people with type 1 diabetes in Latin America. Data from the International Diabetes Mellitus Practices Study (IDMPS). Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2018, 147, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Hariri, M.T.; Al-Enazi, A.S.; Alshammari, D.M.; Bahamdan, A.S.; Al-Khtani, S.M.; Al-Abdulwahab, A.A. Descriptive study on the knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding the diabetic foot. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 2017, 12, 492–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison-Blount, M.; Hashmi, F.; Nester, C.; Williams, A.E. The prevalence of foot problems in an Indian population. Diabet. Foot J. 2017, 20, 95–102. [Google Scholar]

- International Diabetes Federation E-library. Diabetic Foot Screening Pocket Chart. Available online: https://www.idf.org/e-library/guidelines/124-diabetic-foot-screening-pocket-chart.html (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Agha, S.A.; Usman, G.; Agha, M.A.; Anwer, S.H.; Khalid, R.; Raza, F.; Aleem, S. Influence of socio-demographic factors on knowledge and practice of proper diabetic foot care. KMUJ 2014, 6, 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Pourkazemi, A.; Ghanbari, A.; Khojamli, M.; Balo, H.; Hemmati, H.; Jafaryparvar, Z.; Motamed, B. Diabetic foot care: Knowledge and practice. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2020, 20, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayampanathan, A.A.; Cuttilan, A.N.; Pearce, C.J. Barriers and enablers to proper diabetic foot care amongst community dwellers in an Asian population: A qualitative study. Ann. Transl. Med. 2017, 5, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hills, A.P.; Misra, A.; Gill, J.M.R.; Byrne, N.M.; Soares, M.J.; Ramachandran, A.; Palaniappan, L.; Street, S.J.; Jayawardena, R.; Khunti, K.; et al. Public health and health systems: Implications for the prevention and management of type 2 diabetes in south Asia. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018, 6, 992–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaleh, F.M.; AlBassam, K.S.; Alsairafi, Z.K.; Naser, A.Y. Knowledge and practice of foot self-care among patients with diabetes attending primary healthcare centres in Kuwait: A cross-sectional study. Saudi Pharm. J. 2021, 29, 506–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soumya, S.; Ajith, A.K.; Aparna, V.K.; Deepa, V.; Prajisha, V.; Rinsha, C.; Shinumol, V. Risk of Developing Diabetic Foot, Practice and Barriers in Foot Care among Client with Type II Diabetes Mellitus. Int. J. Health Sci. Res. 2016, 6, 310–316. [Google Scholar]

- Saurabh, S.; Sarkar, S.; Selvaraj, K.; Kar, S.; Kumar, S.; Roy, G. Effectiveness of foot care education among people with type 2 diabetes in rural Puducherry, India. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 18, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lung, C.-W.; Wu, F.-L.; Liao, F.; Pu, F.; Fan, Y.; Jan, Y.-K. Emerging technologies for the prevention and management of diabetic foot ulcers. J. Tissue Viability 2020, 29, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvam, S.; Murugesan, N.; Snehalatha, C.; Nanditha, A.; Raghavan, A.; Simon, M.; Susairaj, P.; Ramachandran, A. Health education on diabetes and other non-communicable diseases imparted to teachers shows a cascading effect. A study from Southern India. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2017, 125, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillip, M.; Bergenstal, R.M.; Close, K.L.; Danne, T.; Garg, S.K.; Heinemann, L.; Kovatchev, B.P.; Laffel, L.M.; Kovatchev, B.P.; Mohan, V.; et al. The digital/virtual diabetes clinic: The future is now—Recommendations from an international panel on diabetes digital technologies introduction. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2021, 23, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, A.; Kumar, R.; Nanditha, A.; Raghavan, A.; Snehalatha, C.; Krishnamoorthy, S.; Joshi, P.; Tesfaye, F. mDiabetes initiative using text messages to improve lifestyle and health-seeking behaviour in India. BMJ Innov. 2018, 4, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, Y.; Yusuf, S.; Haryanto, H.; Sumeru, A.; Saryono, S. The barriers and facilitators of foot care practices in diabetic patients in Indonesia: A qualitative study. Nurs. Open 2021, 9, 2867–2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, V.; Shobhana, R.; Snehalatha, C.; Seena, R.; Ramachandran, A. Need for education on foot care in diabetic patients in India. J. Assoc. Physicians India 1999, 47, 1083–1085. [Google Scholar]

- Kanazawa, T.; Nakagami, G.; Goto, T.; Noguchi, H.; Oe, M.; Miyagaki, T.; Hayashi, A.; Sasaki, S.; Sanada, H. Use of smartphone attached mobile thermography assessing subclinical inflammation: A pilot study. J. Wound Care 2016, 25, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, R.; Rajalakshmi, R.; Surya, J.; Ramakrishnan, R.; Sivaprasad, S.; Conroy, D.; Thethi, J.P.; Mohan, V.; Netuveli, G. Impact on health and provision of healthcare services during the COVID-19 lockdown in India: A multicentre cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e043590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nather, A.; Cao, S.; Chen, J.; Low, A. Prevention of diabetic foot complications. Singap. Med. J. 2018, 59, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, N.; Doupis, J. Diabetic foot disease: From the evaluation of the “foot at risk” to the novel diabetic ulcer treatment modalities. World J. Diabetes 2016, 7, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Condition | Perception | Temperature |

|---|---|---|

| Normal | Hot Cold | <42.4 °C >19 °C |

| Mild | Hot Cold | 42.5–45.4 °C 15–19 °C |

| Moderate | Hot Cold | 45.5–48 °C 11–15 °C |

| Severe | Hot Cold | >48 °C <10 °C |

| Condition | ABI | Risk Classification |

|---|---|---|

| Normal | 0.9–1.2 | Risk is small |

| Definite vascular disease | 0.6–0.9 | Risk is moderate and depends on other risk factors |

| Severe vascular disease | Less than 0.6 | Risk is very high |

| Q.No. | Question |

|---|---|

| 1. | Do you inspect your foot regularly? |

| 2. | Do you wear footwear regularly while walking? |

| 3. | Do you wash your feet regularly with warm water? |

| 4. | Do you keep your foot dry? |

| 5. | Do you wear special soft shoes? |

| 6. | Do you apply moisturizer? |

| 7. | Do you go for regular foot monitoring? |

| 8. | Do you regularly check your blood sugar levels? |

| 9. | Do you cut your nails regularly? |

| 10. | Do you report the presence of blisters/corns to a foot specialist? |

| Baseline Characteristics | All Subjects (Mean ± Standard Deviation) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 58 ± 12 | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 55 | |

| Male | 103 | |

| Diabetes duration (year) Type 1 DM Type 2 DM | 11 ± 7 27 131 | |

| Education | ||

| Diploma or no degree | 122 | |

| University degree | 36 | |

| Job profile | ||

| Low | 57 | |

| Medium | 37 | |

| High | 12 | |

| No job | 52 | |

| Diabetic foot characteristics | Present (in %) | Absent (in %) |

| Burning | 50 | 50 |

| Numbness Diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN) Heredity | 49 43 48 | 51 57 52 |

| Trauma | 5 | 95 |

| Deformity | 13 | 87 |

| Foot care training | 60 | 40 |

| History of/leading to amputation | 2 | 98 |

| Special footwear | 18 | 82 |

| Previous other diabetes-related complications | 35 | 65 |

| Diabetic foot ulcer | 6 | 94 |

| Risk Category | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment | Normal Plantar Sensation | Loss of Protective Sensation (LOPS) | LOPS with either High Pressure or Poor Circulation (Peripheral Arterial Disease) or Structural Foot Deformities or Onychomycosis | History of Ulceration, Amputation or Neuropathic Fracture |

| Risk Classification | Low | Moderate | High | Very High |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

B. G., S.; V., U.; Shivaram, J.M.; Belehalli, P.; M. A., S.; H. C., C.; Sikkandar, M.Y.; Brioschi, M.L. Diabetic Foot Assessment and Care: Barriers and Facilitators in a Cross-Sectional Study in Bangalore, India. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5929. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20115929

B. G. S, V. U, Shivaram JM, Belehalli P, M. A. S, H. C. C, Sikkandar MY, Brioschi ML. Diabetic Foot Assessment and Care: Barriers and Facilitators in a Cross-Sectional Study in Bangalore, India. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(11):5929. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20115929

Chicago/Turabian StyleB. G., Sudha, Umadevi V., Joshi Manisha Shivaram, Pavan Belehalli, Shekar M. A., Chaluvanarayana H. C., Mohamed Yacin Sikkandar, and Marcos Leal Brioschi. 2023. "Diabetic Foot Assessment and Care: Barriers and Facilitators in a Cross-Sectional Study in Bangalore, India" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 11: 5929. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20115929

APA StyleB. G., S., V., U., Shivaram, J. M., Belehalli, P., M. A., S., H. C., C., Sikkandar, M. Y., & Brioschi, M. L. (2023). Diabetic Foot Assessment and Care: Barriers and Facilitators in a Cross-Sectional Study in Bangalore, India. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(11), 5929. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20115929