Conducting Violence and Mental Health Research with Female Sex Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Ethical Considerations, Challenges, and Lessons Learned from the Maisha Fiti Study in Nairobi, Kenya

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Setting and Design

2.2. Study Participants and Consultations on Managing COVID-19 Safe Research

2.3. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

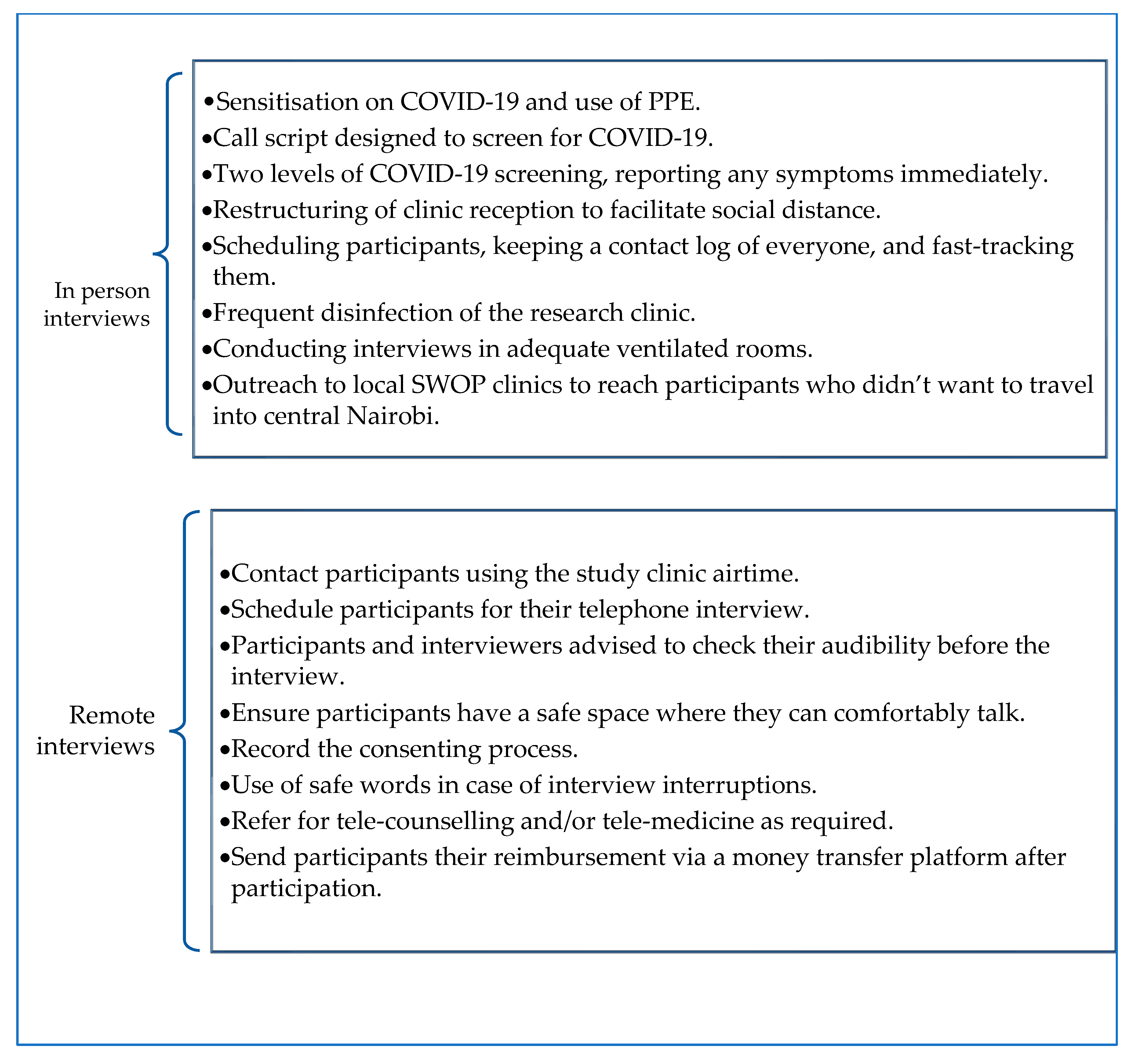

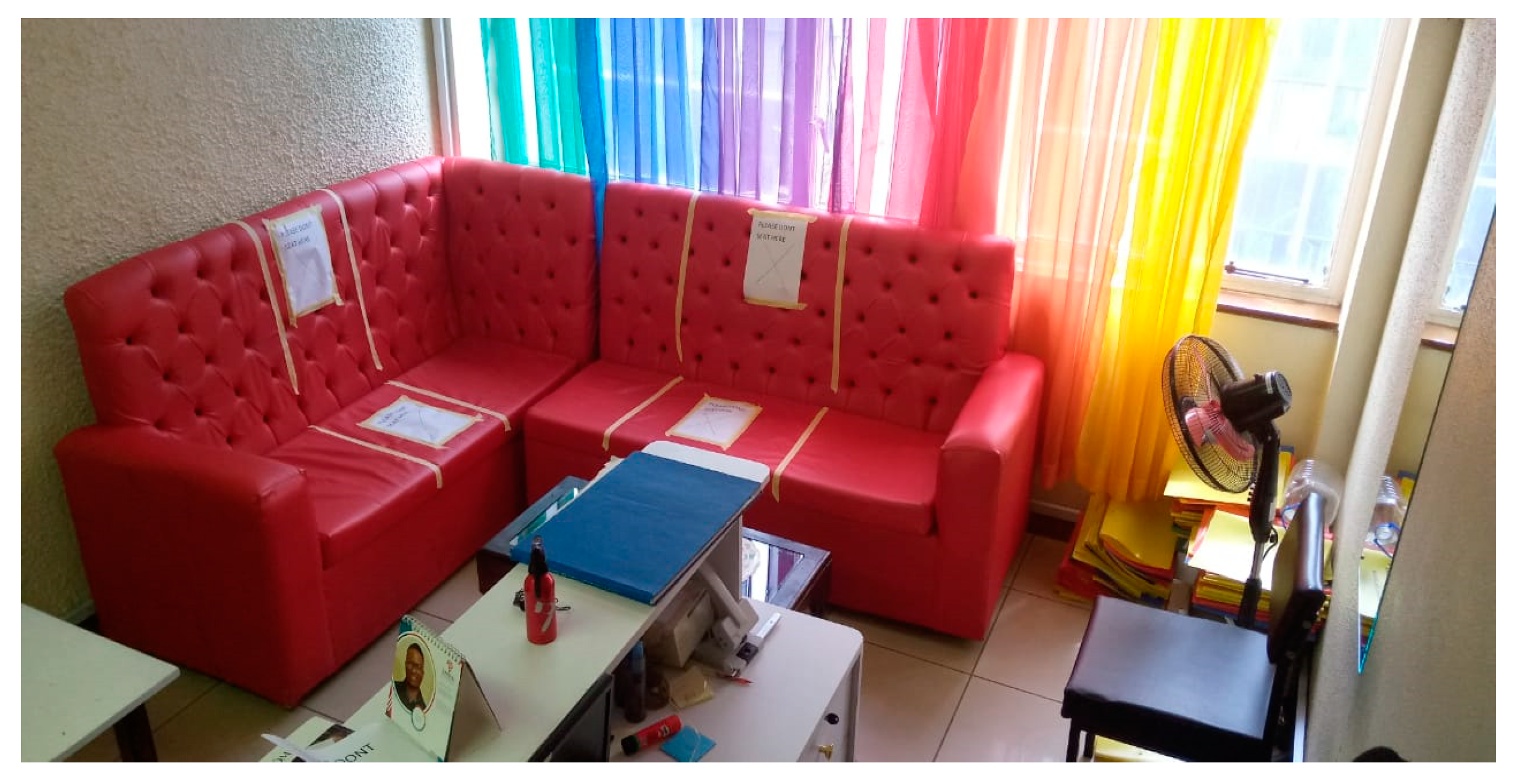

3.1. Modified in-Person Interviews

3.1.1. Implementation of Telephone Interviews

3.1.2. Challenges and Lessons Learned while Conducting in-Person Interviews

3.1.3. Challenges and Lessons Learned while Conducting Phone Interviews

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brand, S.P.C.; Aziza, R.; Kombe, I.K.; Agoti, C.N.; Hilton, J.; Rock, K.S.; Parisi, A.; Nokes, D.J.; Keeling, M.J.; Barasa, E.W. Forecasting the scale of the COVID-19 epidemic in Kenya. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimani, J.; Adhiambo, J.; Kasiba, R.; Mwangi, P.; Were, V.; Mathenge, J.; Macharia, P.; Cholette, F.; Moore, S.; Shaw, S.; et al. The effects of COVID-19 on the health and socio-economic security of sex workers in Nairobi, Kenya: Emerging intersections with HIV. Glob. Public Health 2020, 15, 1073–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, R.; Sanders, T.; Gichuna, S.; Campbell, R.; Mutonyi, M.; Mwangi, P. Informal settlements, COVID-19 and sex workers in Kenya. Urban Stud. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantell, J.E.; Franks, J.; Lahuerta, M.; Omollo, D.; Zerbe, A.; Hawken, M.; Wu, Y.; Odera, D.; El-Sadr, W.M.; Agot, K. Life in the Balance: Young Female Sex Workers in Kenya Weigh the Risks of COVID-19 and HIV. AIDS Behav. 2021, 25, 1323–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, K.; Green, L.; Volpellier, M.; Kidenda, S.; McHale, T.; Naimer, K.; Mishori, R. The impact of COVID-19 on services for people affected by sexual and gender-based violence. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020, 150, 285–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delor, F.; Hubert, M. Revisiting the concept of “vulnerability”. Soc. Sci. Med. 2000, 50, 1557–1570. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10795963/ (accessed on 14 December 2022).

- Baral, S.; Beyrer, C.; Muessig, K.; Poteat, T.; Wirtz, A.; Decker, M.; Sherman, S.; Kerrigan, D. High and disproportionate burden of HIV among female sex workers in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2012, 15, 90–91. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, E. Pandemic sex workers’ resilience: COVID-19 crisis met with rapid responses by sex worker communities. Int. Soc. Work. 2020, 63, 777–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gichuna, S.; Hassan, R.; Sanders, T.; Campbell, R.; Mutonyi, M.; Mwangi, P. Access to Healthcare in a time of COVID-19: Sex Workers in Crisis in Nairobi, Kenya. Glob. Public Health 2020, 15, 1430–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, L.; Elmes, J.; Stevenson, L.; Holt, V.; Rolles, S.; Lancet, R.S.-T. Sex Workers must not Be Forgotten in the COVID-19 Response. 2002. Available online: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)31033-3/fulltext (accessed on 27 January 2021).

- The Global Network of Sex Work Projects (NSWP). COVID-19 and Sex Workers/Sex Worker-Led Organisations COVID-19 and Sex Workers/Sex Worker-Led Organisations; NSWP: Edinburgh, UK, 2022; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Benoit, C.; Unsworth, R. COVID-19, Stigma, and the Ongoing Marginalization of Sex Workers and their Support Organizations. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2021, 51, 331–342. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10508-021-02124-3 (accessed on 20 April 2022). [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.P. COVID-19 and violence: A research call to action. BMC Womens Health 2020, 20, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Women-World Health Organisation Joint Programme. Violence against Women and Girls Data Collection during COVID-19; UN Women: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–5. Available online: https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2020/04/issue-brief-violence-against-women-and-girls-data-collection-during-COVID-19 (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- UN Women. Data Collection on Violence against Women and COVID-19: Decision Tree; UN Women: New York, NY, USA, 2020; p. 1. Available online: https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2020/07/decision-tree-data-collection-on-violence-against-women-and-COVID-19 (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- Bell, K.; Fahmy, E.; Gordon, D. Quantitative conversations: The importance of developing rapport in standardised interviewing. Qual. Quant. 2016, 50, 193–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namy, S.; Dartnall, E. SVRI Knowledge Exchange: Pivoting to Remote Research on Violence against Women During COVID-19; The Sexual Violence Research Initiative (SVRI): Pretoria, South Africa, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Peterman, A.; Bhatia, A.; Guedes, A. Remote Data Collection on Violence against Women during COVID-19: A Conversation with Experts on Ethics, Measurement & Research Priorities; Unicef-Irc: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–16. Available online: https://www.unicef-irc.org/article/1997-remote-data-collection-on-violence-against-women-during-COVID-19-a-conversation-with.html (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Perova, E.; Halim, D. What Factors Exacerbate and Mitigate the Risk of Gender-Based Violence During COVID-19? Insights from a Phone Survey in Indonesia; ©World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury, S.; Ghosh, A. Ethical Considerations of Mental Health Research Amidst COVID-19 Pandemic: Mitigating the Challenges. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2020, 42, 379–381. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33402798/ (accessed on 23 September 2021). [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Kuppili, P.P.; Pattanayak, R.D.; Sagar, R. Ethics in Psychiatric Research: Issues and Recommendations. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2017, 39, 558–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, S.M.; Kass, N.; Mendelson, T.; Bass, J. The ethics of mental health survey research in low- and middle- income countries. Glob. Ment. Health 2016, 3, e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garciía-Moreno, C.; Jansen, H.A.F.M.; Ellsberg, M.; Heise, L.; Watts, C. WHO Multi-Country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence against Women: Initial Results on Prevalence, Health Outcomes and Women’s Responses; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005; 206p. [Google Scholar]

- Beksinska, A.; Shah, P.; Kungu, M.; Kabuti, R.; Babu, H.; Jama, Z.; Panneh, M.; Nyariki, E.; Nyabuto, C.; Okumu, M.; et al. Longitudinal experiences and risk factors for common mental health problems and suicidal behaviours among female sex workers in Nairobi, Kenya. Glob. Ment. Health 2022, 9, 401. Available online: https://pmc/articles/PMC9806968/ (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Chatfield, K.; Schroeder, D.; Guantai, A.; Bhatt, K.; Bukusi, E.; Adhiambo Odhiambo, J.; Cook, J.; Kimani, J. Preventing ethics dumping: The challenges for Kenyan research ethics committees. Res. Ethics. 2021, 17, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Heath. Interim Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations for Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) in Health Care Settings; Ministry of Health: Singapore, 2020; pp. 1–63. Available online: https://www.health.go.ke/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Kenya-IPC_Considerations_For-Health-Care-Settings-1.pdf (accessed on 17 April 2021).

- Hensen, B.; Mackworth-Young, C.R.S.; Simwinga, M.; Abdelmagid, N.; Banda, J.; Mavodza, C.; Doyle, A.M.; Bonell, C.; Weiss, H.A. Remote data collection for public health research in a COVID-19 era: Ethical implications, challenges and opportunities. Health Policy Plan. 2021, 36, 360–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillemin, M.; Barnard, E.; Allen, A.; Stewart, P.; Walker, H.; Rosenthal, D.; Gillam, L. Do Research Participants Trust Researchers or Their Institution? J. Empir. Res. Hum. Res. Ethics. 2018, 13, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, C.H. Effective Engagement Requires Trust and Being Trustworthy. Med. Care 2018, 56, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reñosa, M.D.C.; Mwamba, C.; Meghani, A.; West, N.S.; Hariyani, S.; Ddaaki, W.; Sharma, A.; Beres, L.K.; McMahon, S. Selfie consents, remote rapport, and Zoom debriefings: Collecting qualitative data amid a pandemic in four resource-constrained settings. BMJ Glob. Health 2021, 6, e004193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Unforeseen Challenges | Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|

| (i) Conducting face-to-face interviews | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| (ii) Conducting remote interviews | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kung’u, M.; Kabuti, R.; Babu, H.; on behalf of The Maisha Fiti Study Champions; Nyamweya, C.; Okumu, M.; Mahero, A.; Jama, Z.; Ngurukiri, P.; Nyariki, E.; et al. Conducting Violence and Mental Health Research with Female Sex Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Ethical Considerations, Challenges, and Lessons Learned from the Maisha Fiti Study in Nairobi, Kenya. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5925. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20115925

Kung’u M, Kabuti R, Babu H, on behalf of The Maisha Fiti Study Champions, Nyamweya C, Okumu M, Mahero A, Jama Z, Ngurukiri P, Nyariki E, et al. Conducting Violence and Mental Health Research with Female Sex Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Ethical Considerations, Challenges, and Lessons Learned from the Maisha Fiti Study in Nairobi, Kenya. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(11):5925. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20115925

Chicago/Turabian StyleKung’u, Mary, Rhoda Kabuti, Hellen Babu, on behalf of The Maisha Fiti Study Champions, Chrispo Nyamweya, Monica Okumu, Anne Mahero, Zaina Jama, Polly Ngurukiri, Emily Nyariki, and et al. 2023. "Conducting Violence and Mental Health Research with Female Sex Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Ethical Considerations, Challenges, and Lessons Learned from the Maisha Fiti Study in Nairobi, Kenya" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 11: 5925. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20115925

APA StyleKung’u, M., Kabuti, R., Babu, H., on behalf of The Maisha Fiti Study Champions, Nyamweya, C., Okumu, M., Mahero, A., Jama, Z., Ngurukiri, P., Nyariki, E., Panneh, M., Shah, P., Beksinska, A., Irungu, E., Adhiambo, W., Muthoga, P., Kaul, R., Weiss, H. A., Seeley, J., ... Beattie, T. S. (2023). Conducting Violence and Mental Health Research with Female Sex Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Ethical Considerations, Challenges, and Lessons Learned from the Maisha Fiti Study in Nairobi, Kenya. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(11), 5925. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20115925