Predictors of Mental Health Literacy among Parents, Guardians, and Teachers of Adolescents in West Malaysia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

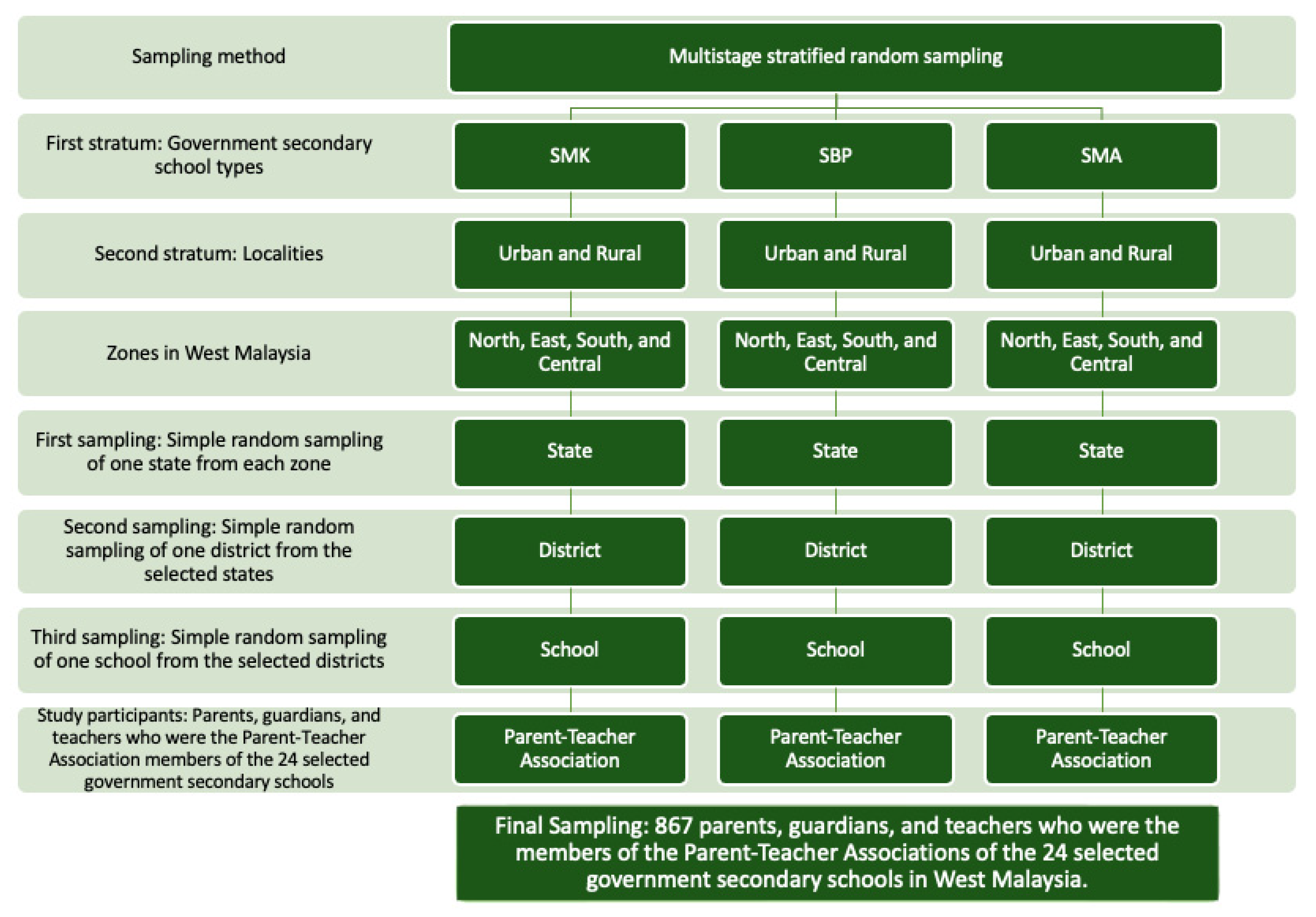

2.1. Study Design and Subjects

2.2. Instrument

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Ethical Consideration

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Common Stigma and Misconceptions

4.2. Association between Participants’ Roles and their Responses

4.3. Predictors of MHL

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IHME. Global Burden of Disease Visualisations. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Available online: https://www.thelancet.com/lancet/visualisations/gbd-compare (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- WHO. Adolescent Health. World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/adolescent-health#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- Kessler, R.C.; Paul Amminger, G.; Aguilar-Gaxiola, S.; Alonso, J.; Lee, S.; Ustun, T.B. Age of Onset of Mental Disorders: A Review of Recent Literature. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2007, 20, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solmi, M.; Radua, J.; Olivola, M.; Croce, E.; Soardo, L.; Salazar de Pablo, G.; il Shin, J.; Kirkbride, J.B.; Jones, P.; Kim, J.H.; et al. Age at Onset of Mental Disorders Worldwide: Large-Scale Meta-Analysis of 192 Epidemiological Studies. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, S.K.; Pheh, K.S.; Lim, Y.; Tan, S.A. Help Seeking Barrier of Malaysian Private University Students. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Disciplines in Humanities and Social Sciences (DHSS-2016), Bangkok, Thailand, 26–27 April 2016; pp. 48–54. [Google Scholar]

- Aida, J.; Azimah, M.N.; Mohd Radzniwan, A.R.; Iryani, M.D.T.; Ramli, M.; Khairani, O. Barriers to the Utilization of Primary Care Services for Mental Health Prolems among Adolescents in a Secondary School in Malaysia. Malays. Fam. Physician 2010, 5, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Umpierre, M.; Meyers, L.V.; Ortiz, A.; Paulino, A.; Rodriguez, A.R.; Miranda, A.; Rodriguez, R.; Kranes, S.; McKay, M.M. Understanding Latino Parents’ Child Mental Health Literacy: Todos a Bordo/All Aboard. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2015, 25, 607–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frauenholtz, S.; Mendenhall, A.N.; Moon, J. Role of School Employees’ Mental Health Knowledge in Interdisciplinary Collaborations to Support the Academic Success of Students Experiencing Mental Health Distress. Child Sch. 2017, 39, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorm, A.F.; Korten, A.E.; Jacomb, P.A.; Christensen, H.; Rodgers, B.; Pollitt, P. “Mental Health Literacy”: A Survey of the Public’s Ability to Recognise Mental Disorders and Their Beliefs about the Effectiveness of Treatment. Med. J. Aust. 1997, 166, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutcher, S.; Bagnell, A.; Wei, Y. Mental Health Literacy in Secondary Schools. A Canadian Approach. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2015, 24, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutcher, S.; Wei, Y.; Coniglio, C. Mental Health Literacy: Past, Present, and Future. Can. J. Psychiatry 2016, 61, 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Midin, M.; Zainal, N.Z.; Lee, T.C.; Ibrahim, N. Mental Health Services in Malaysia. Taiwan. J. Psychiatry 2018, 32, 281–293. [Google Scholar]

- Tay, K.W.; Ong, A.W.H.; Pheh, K.S.; Low, S.K.; Tan, C.S.; Low, P.K. Assessing the Effectiveness of a Mental Health Literacy Programme for Refugee Teachers in Malaysia. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 26, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, C.; Evans-Lacko, S.; Flach, C.; Thornicroft, G. Responses to Mental Health Stigma Questions: The Importance of Social Desirability and Data Collection Method. Can. J. Psychiatry 2012, 57, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doumit, C.A.; Haddad, C.; Sacre, H.; Salameh, P.; Akel, M.; Obeid, S.; Akiki, M.; Mattar, E.; Hilal, N.; Hallit, S.; et al. Knowledge, Attitude and Behaviors towards Patients with Mental Illness: Results from a National Lebanese Study. PLoS One 2019, 14, e222172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phoa, P.K.A.; Razak, A.A.; Kuay, H.S.; Ghazali, A.K.; Rahman, A.A.; Husain, M.; Bakar, R.S.; Gani, F.A. The Malay Literacy of Suicide Scale: A Rasch Model Validation and Its Correlation with Mental Health Literacy among Malaysian Parents, Caregivers and Teachers. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalky, H.F.; Abu-Hassan, H.H.; Dalky, A.F.; Al-Delaimy, W. Assessment of Mental Health Stigma Components of Mental Health Knowledge, Attitudes and Behaviors Among Jordanian Healthcare Providers. Community Ment. Health J. 2020, 56, 524–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutiso, V.N.; Musyimi, C.W.; Nayak, S.S.; Musau, A.M.; Rebello, T.; Nandoya, E.; Tele, A.K.; Pike, K.; Ndetei, D.M. Stigma-Related Mental Health Knowledge and Attitudes among Primary Health Workers and Community Health Volunteers in Rural Kenya. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2017, 63, 508–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sin, J.; Murrells, T.; Spain, D.; Norman, I.; Henderson, C. Wellbeing, Mental Health Knowledge and Caregiving Experiences of Siblings of People with Psychosis, Compared to Their Peers and Parents: An Exploratory Study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2016, 51, 1247–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurley, D.; Swann, C.; Allen, M.S.; Ferguson, H.L.; Vella, S.A. A Systematic Review of Parent and Caregiver Mental Health Literacy. Community Ment. Health J. 2020, 56, 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans-Lacko, S.; Little, K.; Meltzer, H.; Rose, D.; Rhydderch, D.; Henderson, C.; Thornicroft, G. Development and Psychometric Properties of the Mental Health Knowledge Schedule. Can. J. Psychiatry 2010, 55, 440–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pheh, K.S.; Anna Ong, W.H.; Low, S.K.; Tan, C.S.; Kok, J.K. The Malay Version of the Mental Health Knowledge Schedule: A Preliminary Study. Malays. J. Psychiatry 2017, 26, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- DiStefano, C.; Shi, D.; Morgan, G.B. Collapsing Categories Is Often More Advantageous than Modeling Sparse Data: Investigations in the CFA Framework. Struct. Equ. Model. 2021, 28, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupa, T.; Kirsh, B.; Cockburn, L.; Gewurtz, R. Understanding the Stigma of Mental Illness in Employment. Work 2009, 33, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanafiah, A.N.; van Bortel, T. A Qualitative Exploration of the Perspectives of Mental Health Professionals on Stigma and Discrimination of Mental Illness in Malaysia. Int. J. Ment Health Syst. 2015, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razali, S.M.; Najib, M.A.M. Help-Seeking Pathways among Malay Psychiatric Patients. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2000, 46, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, M.S.; Subhi, N.; Zakaria, E. Cultural Influences in Mental Health Help-Seeking among Malaysian Family Caregivers Article In. Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2014, 22, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Schönfeld, P.; Brailovskaia, J.; Bieda, A.; Zhang, X.C.; Margraf, J. The Effects of Daily Stress on Positive and Negative Mental Health: Mediation through Self-Efficacy. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2016, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zisook, S.; Shear, K. Grief and Bereavement: What Psychiatrists Need to Know? World Psychiatry 2009, 8, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, S.C.; Brega, A.G.; Crutchfield, T.M.; Elasy, T.; Herr, H.; Kaphingst, K.; Karter, A.J.; Moreland-Russell, S.; Osborn, C.Y.; Pignone, M.; et al. Update on Health Literacy and Diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2014, 40, 581–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schillinger, D.; Barton, L.R.; Karter, A.J.; Wang, F.; Adler, N. Does Literacy Mediate the Relationship between Education and Health Outcomes? A Study of a Low-Income Population with Diabetes. Public Health Rep. 2006, 121, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adu, P.; Jurcik, T.; Grigoryev, D. Mental Health Literacy in Ghana: Implications for Religiosity, Education and Stigmatization. Transcult. Psychiatry 2021, 58, 516–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.L.; Watt, S.E.; Noble, W.; Shanley, D.C. Knowledge of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and Attitudes toward Teaching Children with ADHD: THE Role of Teaching Experience. Psychol. Sch. 2012, 49, 511–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekle, B. Knowledge and Attitudes about Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): A Comparison between Practicing Teachers and Undergraduate Education Students Introduction Background and Definition. J. Atten. Disord. 2004, 7, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.; Williford, A.; Mendenhall, A. Educators’ Perceptions of Youth Mental Health: Implications for Training and the Promotion of Mental Health Services in Schools. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 2017, 73, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dods, J. Teacher Candidate Mental Health and Mental Health Literacy. Except. Educ. Int. 2016, 26, 42–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni Chorcora, E.; Swords, L. Mental Health Literacy and Help-Giving Responses of Irish Primary School Teachers. Ir. Educ. Stud. 2021, 41, 735–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munawar, K.; Mukhtar, F.; Choudhry, F.R.; Ng, A.L.O. Mental Health Literacy: A Systematic Review of Knowledge and Beliefs about Mental Disorders in Malaysia. Asia-Pac. Psychiatry 2022, 14, e12475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health Malaysia. The National Strategic Plan For Mental Health 2020–2025; Ministry of Health Malaysia: Putrajaya, Malaysia, 2020.

- Tonsing, K.N. A Review of Mental Health Literacy in Singapore. Soc. Work Health Care 2018, 57, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razali, S.M.; Ismail, Z. Public Stigma towards Patients with Schizophrenia of Ethnic Malay: A Comparison between the General Public and Patients’ Relatives. J. Ment. Health 2014, 23, 176–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, Y.P.; Rashid, A.; O’Brien, F. Determining the Effectiveness of a Video-Based Contact Intervention in Improving Attitudes of Penang Primary Care Nurses towards People with Mental Illness. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0187861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, A.; Tan, K.-A.; Knaak, S.; Chew, B.H.; Ghazali, S.S. Effects of Brief Psychoeducational Program on Stigma in Malaysian Pre-Clinical Medical Students: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Acad. Psychiatry 2016, 40, 905–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, M.D.A.; Morrison, R.S. Study Design, Precision, and Validity in Observational Studies. J. Palliat. Med. 2009, 12, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | n (%) | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 43.81 (8.34) | |

| Role | ||

| Parents or caretakers | 560 (64.6) | |

| Teacher | 307 (35.4) | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 247 (28.5) | |

| Female | 620 (71.5) | |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Malay | 755 (87.1) | |

| Chinese | 49 (5.7) | |

| Indian | 4 (0.5) | |

| Other Bumiputera | 48 (5.5) | |

| Others | 11 (1.3) | |

| Religion | ||

| Islam | 779 (89.9) | |

| Christian | 49 (5.7) | |

| Hindu | 3 (0.3) | |

| Buddhist | 34 (3.9) | |

| Others | 2 (0.2) | |

| Education level | ||

| No formal education | 2 (0.2) | |

| Primary education | 11 (1.3) | |

| Secondary education | 202 (23.3) | |

| Tertiary education | 652 (75.2) | |

| Occupation sector | ||

| Unemployed/homemaker | 102 (11.8) | |

| Government | 578 (66.7) | |

| Private | 106 (12.2) | |

| Self-employed | 63 (7.3) | |

| Pensioner | 18 (2.1) | |

| Monthly household income bracket a | ||

| B40 | 346 (39.9) | |

| M40 | 394 (45.4) | |

| T20 | 127 (14.6) | |

| School locality | ||

| Urban | 502 (58.1) | |

| Rural | 363 (41.9) | |

| School type | ||

| SMK | 341 (39.3) | |

| SBP | 321 (37.0) | |

| SMA | 205 (23.6) | |

| Personal history of mental illness | ||

| Yes | 21 (2.4) | |

| No | 846 (97.6) | |

| Had known someone with mental illness | ||

| Yes | 160 (18.5) | |

| No | 707 (81.5) | |

| Had assisted those with mental illness | ||

| Yes | 217 (25.0) | |

| No | 650 (75.0) | |

| Had attended formal psychological first aid training | ||

| Yes | 88 (10.1) | |

| No | 779 (89.9) |

| Role | Item | Dimension | Part | Favorable Responses n (%) | Non-Favorable Responses n (%) | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parents and guardians (n = 560) | MAKS-M 1 | Employment | A (Knowledge of mental health stigma) | 262 (46.8) | 298 (53.2) | 43.65 (4.03) |

| MAKS-M 2 | Support | 466 (83.2) | 94 (16.8) | |||

| MAKS-M 3 | Psychotropic drugs | 291 (52.0) | 269 (48.0) | |||

| MAKS-M 4 * | Psychotherapy | 475 (84.8) | 85 (15.2) | |||

| MAKS-M 5 | Recovery | 298 (53.2) | 262 (48.0) | |||

| MAKS-M 6 ** | Help-seeking | 91 (16.3) | 469 (83.7) | |||

| MAKS-M 7 ** | Depression | B (Knowledge on the diagnosis of mental disorders) | 508 (90.7) | 52 (9.3) | ||

| MAKS-M 8 ** | Stress | 24 (4.3) | 536 (95.7) | |||

| MAKS-M 9 ** | Schizophrenia | 442 (78.9) | 118 (21.1) | |||

| MAKS-M 10 ** | Bipolar | 444 (79.3) | 116 (20.7) | |||

| MAKS-M 11 | Addiction | 369 (65.9) | 191 (34.1) | |||

| MAKS-M 12 ** | Grief | 46 (8.2) | 514 (91.8) | |||

| Teachers (n = 307) | MAKS-M 1 | Employment | A (Knowledge of mental health stigma) | 146 (47.6) | 161 (52.4) | 44.15 (4.13) |

| MAKS-M 2 | Support | 245 (80.0) | 62 (20.0) | |||

| MAKS-M 3 | Psychotropic drugs | 171 (55.7) | 136 (44.3) | |||

| MAKS-M 4 * | Psychotherapy | 278 (90.6) | 29 (9.4) | |||

| MAKS-M 5 | Recovery | 176 (57.3) | 131 (42.7) | |||

| MAKS-M 6 ** | Help-seeking | 73 (23.8) | 234 (76.2) | |||

| MAKS-M 7 ** | Depression | B (Knowledge on the diagnosis of mental disorders) | 295 (96.1) | 12 (3.9) | ||

| MAKS-M 8 ** | Stress | 28 (9.1) | 279 (90.9) | |||

| MAKS-M 9 ** | Schizophrenia | 268 (87.3) | 39 (12.7) | |||

| MAKS-M 10 ** | Bipolar | 272 (88.6) | 35 (11.4) | |||

| MAKS-M 11 | Addiction | 196 (63.8) | 111 (36.1) | |||

| MAKS-M 12 ** | Grief | 44 (14.3) | 263 (86.7) | |||

| The overall mean score of the study population | 43.82 (4.07) | |||||

| Variables | Simple Linear Regression | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| b | 95% CI | p-Value | |

| Known someone with mental health disorder a, b | 1.588 | 0.896, 2.280 | <0.001 |

| Monthly household income bracket a, b | 0.602 | 0.213, 0.991 | 0.002 |

| Age a, b | −0.032 | −0.064, 0.001 | 0.057 |

| Attended formal psychological first aid training a, b | 1.221 | 0.325, 2.116 | 0.008 |

| Role a | −0.500 | −1.067, 0.067 | 0.084 |

| Sex a | −0.682 | −1.282, −0.082 | 0.026 |

| Ethnicity a | −0.271 | −0.596, 0.054 | 0.102 |

| Religion a | −0.463 | −0.997, 0.071 | 0.089 |

| Education level a | 0.682 | 0.123, 1.241 | 0.017 |

| Occupation sector | −0.032 | −0.363, 0.299 | 0.851 |

| School locality a | 0.403 | −0.147, 0.952 | 0.151 |

| School type a | −0.137 | −0.486, 0.212 | 0.440 |

| Personal diagnosis of mental health disorders a | 1.157 | −0.608, 2.921 | 0.199 |

| Assisted someone with mental health disorders a | 0.746 | 0.121, 1.370 | 0.019 |

| Variables | Multiple Linear Regression | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Adj. b | 95% CI | p-Value | |

| Known someone with a mental health disorder (1 = Yes, 0 = No) | 1.385 | 0.691, 2.080 | <0.001 |

| Monthly household income bracket | |||

| B40 | |||

| M40 | 0.709 | 0.122, 1.296 | 0.018 |

| T20 | 1.341 | 0.502, 2.180 | 0.002 |

| Age | −0.040 | −0.073, −0.007 | 0.018 |

| Attended formal psychological first aid training (1 = Yes, 0 = No) | 1.016 | 0.134, 1.904 | 0.025 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Phoa, P.K.A.; Ab Razak, A.; Kuay, H.S.; Ghazali, A.K.; Ab Rahman, A.; Husain, M.; Bakar, R.S.; Abdul Gani, F. Predictors of Mental Health Literacy among Parents, Guardians, and Teachers of Adolescents in West Malaysia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 825. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010825

Phoa PKA, Ab Razak A, Kuay HS, Ghazali AK, Ab Rahman A, Husain M, Bakar RS, Abdul Gani F. Predictors of Mental Health Literacy among Parents, Guardians, and Teachers of Adolescents in West Malaysia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(1):825. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010825

Chicago/Turabian StylePhoa, Picholas Kian Ann, Asrenee Ab Razak, Hue San Kuay, Anis Kausar Ghazali, Azriani Ab Rahman, Maruzairi Husain, Raishan Shafini Bakar, and Firdaus Abdul Gani. 2023. "Predictors of Mental Health Literacy among Parents, Guardians, and Teachers of Adolescents in West Malaysia" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 1: 825. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010825

APA StylePhoa, P. K. A., Ab Razak, A., Kuay, H. S., Ghazali, A. K., Ab Rahman, A., Husain, M., Bakar, R. S., & Abdul Gani, F. (2023). Predictors of Mental Health Literacy among Parents, Guardians, and Teachers of Adolescents in West Malaysia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 825. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010825