When Is Authoritarian Leadership Less Detrimental? The Role of Leader Capability

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theory and Hypotheses

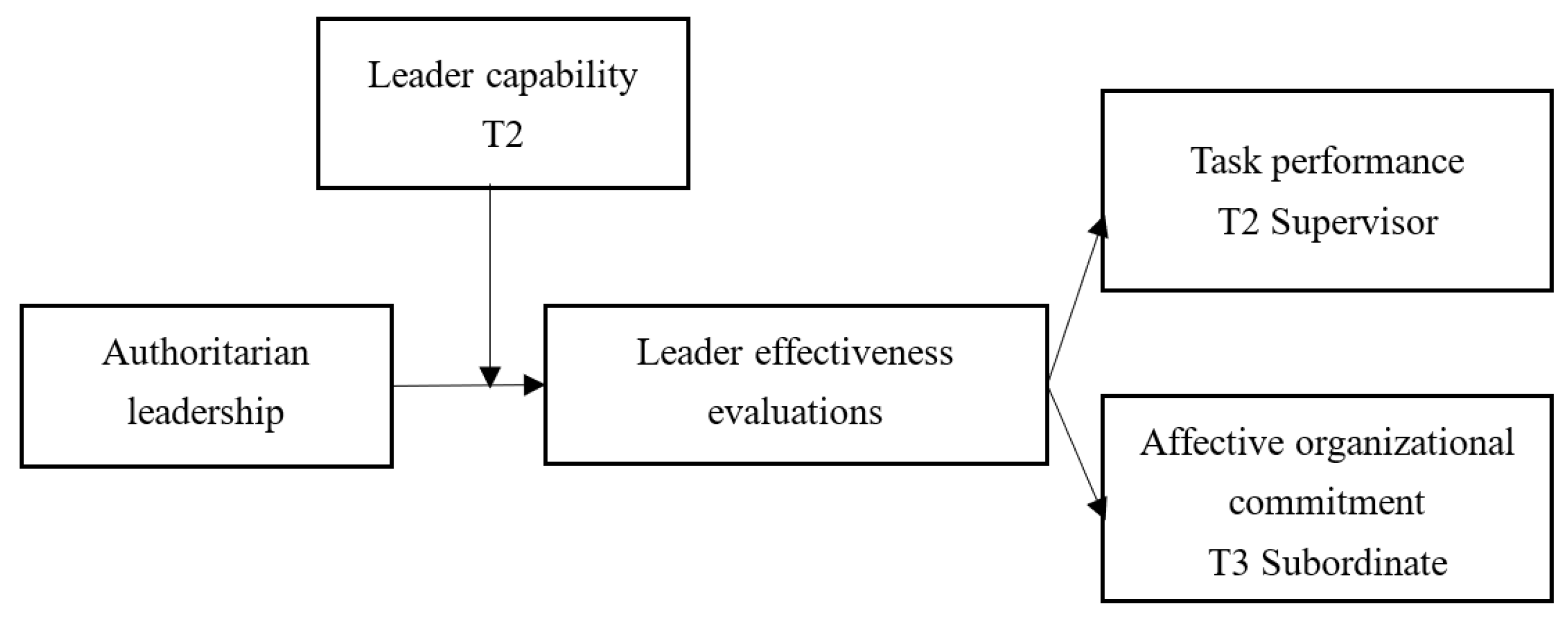

2.1. Authoritarian Leadership, Leader Effectiveness Evaluation, and Employee Outcomes

2.2. The Moderating Role of Leader Capability

2.3. Methods Review

3. Methods

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.3. Analytical Strategy

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary Analysis

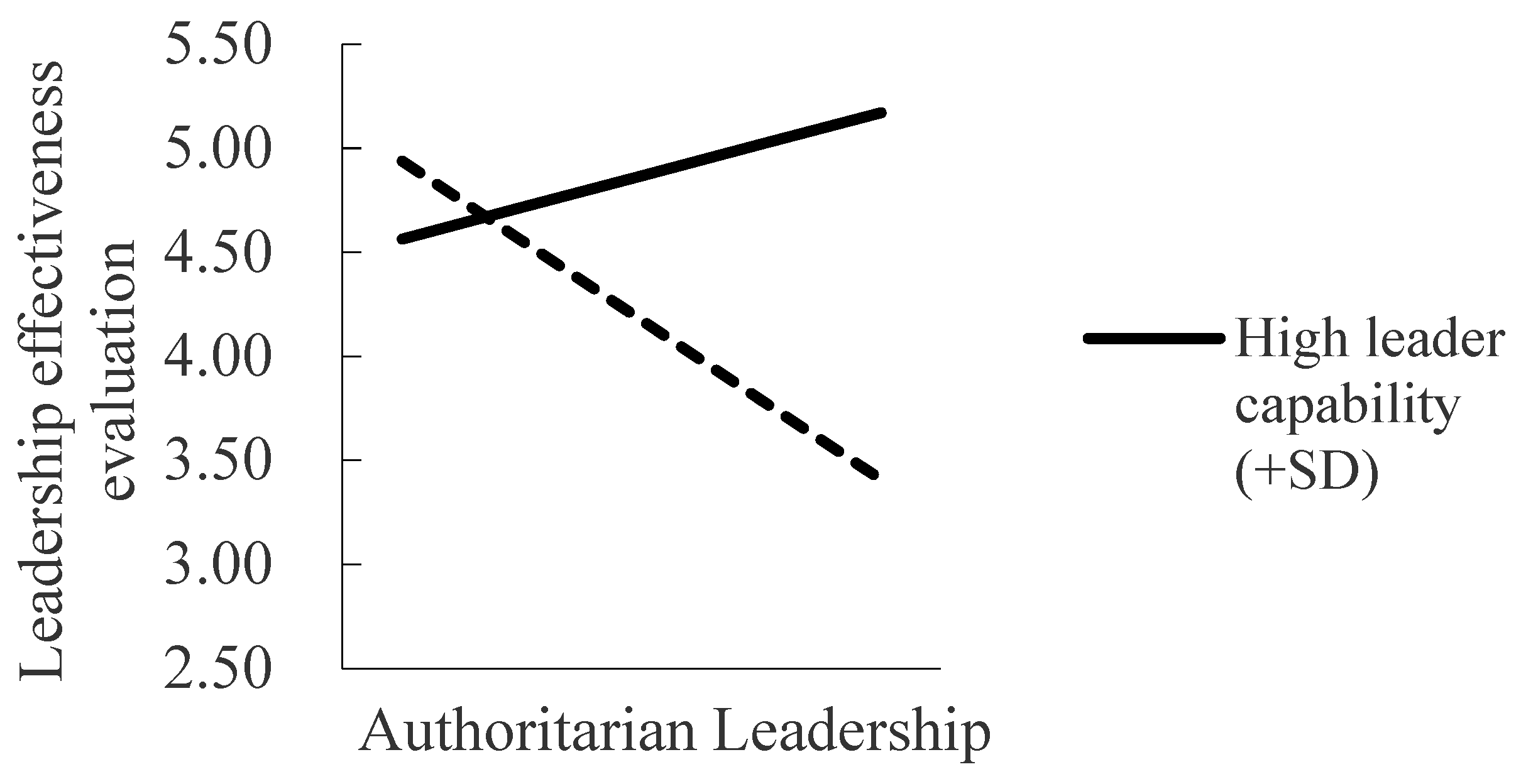

4.2. Hypotheses Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Result Discussions

5.2. Conclusions

5.3. Limitations and Further Research

5.4. Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Farh, J.L.; Cheng, B.S. A cultural analysis of paternalistic leadership in Chinese organizations. In Management and Organizations in the Chinese Context; Li, J.T., Tsui, A.S., Weldon, E., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2000; pp. 94–127. [Google Scholar]

- Farh, J.L.; Cheng, B.; Chou, L.F.; Chu, X. Authority and benevolence: Employee’s responses to paternalistic leadership in. China. In China’s Domestic Private Firms: Multidisciplinary Perspectives on Management and Performance; Tsui, A.S., Bian, Y., Cheng, L., Eds.; M.E. Sharpe: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 230–260. [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini, E.K.; Scandura, T.A. Paternalistic Leadership: A Review and Agenda for Future Research. J. Manag. 2008, 34, 566–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.; Chou, L.; Wu, T.; Huang, M.; Farh, J. Paternalistic leadership and subordinate responses: Establishing a leader. ship. model in Chinese organizations. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 7, 89–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farh, J.L.; Liang, J.; Chou, L.F.; Cheng, B.S. Paternalistic leadership in Chinese Organizations: Research progress and future research direction. In Leadership and Management in China: Philosophies, Theories, and Practices; Chen, C.C., Lee, Y.T., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: London, UK, 2008; pp. 171–205. [Google Scholar]

- Schaubroeck, J.M.; Shen, Y.; Chong, S. A dual-stage moderated mediation model linking authoritarian leadership to fol. lower outcomes. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koveshnikov, A.; Ehrnrooth, M.; Wechtler, H. Authoritarian and benevolent leadership: The role of follower homophily, power. distance orientation and employability. Pers. Rev. 2022; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Chen, X.; Wei, H. How do authoritarian and benevolent leadership affect employee work–family conflict? An emo tional. regulation perspective. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2022, 4, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, L.; Decoster, S.; Babalola, M.T.; De Schutter, L.; Garba, O.A.; Riisla, K. Authoritarian leadership and employee creativ. ity: The moderating role of psychological capital and the mediating role of fear and defensive silence. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 92, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xie, Y. Authoritarian Leadership and Extra-Role Behaviors: A Role-Perception Perspective. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2017, 13, 147–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Huang, X.; Chan, S.C.H. The influencing mechanisms of paternalistic leadership in Mainland China. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2012, 18, 631–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Huang, X.; Li, C.; Liu, W. Perceived Interactional Justice and Trust-in-supervisor as Mediators for Paternalistic Leadership. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2012, 8, 97–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Liang, J.; Chen, M. The Danger of Blindly Following: Examining the Relationship Between Authoritarian Leadership and Unethical Pro-organizational Behaviors. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2021, 17, 524–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.C.H.; Huang, X.; Snape, E.; Lam, C.K. The Janus face of paternalistic leaders: Authoritarianism, benevolence, subor dinates’ organization-based self-esteem, and performance. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 108–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Bao, C.; Huang, C.; Brinsfield, C.T. Authoritarian leadership and employee silence in China. J. Manag. Organ. 2018, 24, 62–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Huai, M.; Xie, Y. Paternalistic leadership and employee voice in China: A dual process model. Leadersh. Q. 2015, 26, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Liu, Y.; Hua, C.; Lo, H.; Yeh, Y. Too unsafe to voice? Authoritarian leadership and employee voice in Chinese organizations. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2020, 58, 527–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Graham, L.; Farh, J.; Huang, X. The Impact of Authoritarian Leadership on Ethical Voice: A Moderated Mediation Model of Felt Uncertainty and Leader Benevolence. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 170, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, H.; Luo, J. How Do Authoritarian Leadership and Abusive Supervision Jointly Thwart Follower Proactivity? A Social Control Perspective. J. Manag. 2019, 47, 930–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla, A.; Hogan, R.; Kaiser, R.B. The toxic triangle: Destructive leaders, susceptible followers, and conducive environments. Leadersh. Q. 2007, 18, 176–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harms, P.D.; Wood, D.; Landay, K.; Lester, P.B.; Vogelgesang Lester, G. Autocratic leaders and authoritarian followers revisited: A review and agenda for the future. Leadersh. Q. 2018, 29, 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Chou, W.; Schaubroeck, J.M. The roles of relational identification and workgroup cultural values in linking authoritarian leadership to employee performance. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2019, 28, 498–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, M.; Zhao, H.; Ma, C.; Zhang, L. Discipline vs. dominance: The relationships between different types of authoritarian leadership and employee self-interested voice. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Chen, Y.; Sun, P.; Li, C. Authoritarian leadership and employees’ unsafe behaviors: The mediating roles of organizational cynicism and work alienation. Curr. Psychol. 2019, 38, 1668–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; Sanchez, J.I. Does paternalistic leadership promote innovative behavior? The interaction between authoritarianism and benevolence. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2017, 47, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Eberly, M.B.; Chiang, T.; Farh, J.; Cheng, B. Affective Trust in Chinese Leaders: Linking Paternalistic Leadership to Employee Performance. J. Manag. 2014, 40, 796–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Weng, Q. Authoritarian-Benevolent Leadership and Employee Behaviors: An Examination of the Role of LMX Ambivalence. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Guan, B. The Positive Effect of Authoritarian Leadership on Employee Performance: The Moderating Role of Power Distance. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhl-Bien, M.; Riggio, R.E.; Lowe, K.B.; Carsten, M.K. Followership theory: A review and research agenda. Leadersh. Q. 2014, 25, 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, R.G.; Brown, D.J.; Harvey, J.L.; Hall, R.J. Contextual constraints on prototype generation and their multilevel consequences for leadership perceptions. Leadersh. Q. 2001, 12, 311–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhou, X.; Klyver, K. Collective Efficacy: Linking Paternalistic Leadership to Organizational Commitment. J. Bus. Ethics. 2019, 159, 587–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Knippenberg, D. Embodying who we are: Leader group prototypicality and leadership effectiveness. Leadersh. Q. 2011, 22, 1078–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukl, G. Contingency theories of effective leadership. In The Sage Handbook of Leadership; Bryman, A., Ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011; pp. 286–298. [Google Scholar]

- Hogg, M.A.; Hains, S.C.; Mason, I. Identification and leadership in small groups: Salience, frame of reference, and leader. stereo typicality effects on leader evaluations. J. Per. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 75, 1248–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiedler, F.E.A. Contingency Model of Leadership Effectiveness. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1964, 1, 49–190. [Google Scholar]

- Ayman, R.; Chemers, M.M.; Fiedler, F. The contingency model of leadership effectiveness: Its levels of analysis. Leadersh. Q. 1995, 6, 147–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, J.R.; Raven, B.; Cartwright, D. The bases of social power. Class. Organ. Theory 1959, 7, 311–320. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, B.; Boer, D.; Chou, L.; Huang, M.; Yoneyama, S.; Shim, D.; Sun, J.; Lin, T.; Chou, W.; Tsai, C. Paternalistic Leadership in Four East Asian Societies: Generalizability and Cultural Differences of the Triad Model. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2014, 45, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Knippenberg, B.; van Knippenberg, D. Leader self-sacrifice and leadership effectiveness: The moderating role of leader prototypicality. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossek, E.E.; Huang, J.L.; Piszczek, M.M.; Fleenor, J.W.; Ruderman, M. Rating Expatriate Leader Effectiveness in Multisource Feedback Systems: Cultural Distance and Hierarchical Effects. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 56, 151–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, S.R.; Côté, S.; Woodruff, T. Echoes of Our Upbringing: How Growing Up Wealthy or Poor Relates to Narcissism, Leader Behavior, and Leader Effectiveness. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 59, 2157–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochazka, J.; Vaculik, M.; Smutny, P.; Jezek, S. Leader traits, transformational leadership and leader effectiveness: A mediation study from the Czech Republic. J. East Eur. Manag. Stud. 2018, 23, 474–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giessner, S.R.; van Knippenberg, D.; Sleebos, E. License to fail? How leader group prototypicality moderates the effects of. leader performance on perceptions of leadership effectiveness. Leadersh. Q. 2009, 20, 434–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, M.A. A Social Identity Theory of Leadership. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2001, 5, 184–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremer, D.D.; Knippenberg, D.V. Leader self-sacrifice and leadership effectiveness: The moderating role of leader self-confidence. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2004, 95, 140–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breevaart, K.; Zacher, H. Main and interactive effects of weekly transformational and laissez-faire leadership on followers’ trust in the leader and leader effectiveness. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2019, 92, 384–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsui, A.S.; Wang, H.; Xin, K.; Zhang, L.; Fu, P.P. “Let a thousand flowers bloom”: Variation of leadership styles among Chinese CEOs. Organ. Dyn. 2004, 33, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.C. Paternalistic leadership and employee voice: Does information sharing matter? Hum. Relat. 2014, 67, 667–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.Y.; Tsui, A.S.; Wang, D.X. Leadership behaviors and group creativity in Chinese organizations: The role of group processes. Leadersh. Q. 2011, 22, 851–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahan, P.; Theilacker, M.; Adamovic, M.; Choi, D.; Harley, B.; Healy, J.; Olsen, J.E. Between fit and flexibility? The benefits of high-performance work practices and leadership capability for innovation outcomes. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2020, 31, 414–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.W.H. Transformational leadership and performance outcomes: Analyses of multiple mediation pathways. Leadersh. Q. 2017, 28, 385–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J. A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 1991, 1, 61–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Demerouti, E.; Le Blanc, P. Transformational leadership, adaptability, and job crafting: The moderating role of organizational identification. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 100, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Wang, G.; Zheng, X.; Liu, T.; Miao, Q. Examining the Role of Personal Identification With the Leader in Leadership Effectiveness: A Partial Nomological Network. Group. Organ. Manag. 2013, 38, 36–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiedler, F.E. The Contingency Model and the Dynamics of the Leadership Process. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1978, 11, 59–112. [Google Scholar]

- Ayman, R.; Chemers, M.M. The Effect of Leadership Match on Subordinate Satisfaction in Mexican Organisations: Some Moderating Influences of Self-monitoring. Appl. Psychol. 1991, 40, 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raven, B.H. The Bases of Power and the Power/Interaction Model of Interpersonal Influence. Anal. Soc. Issues Public Policy 2008, 8, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.B.; Slaughter, J.E.; Ellis, A.P.J.; Rivin, J.M. Gender and the evaluation of humor at work. J. Appl. Psychol. 2019, 104, 1077–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, F.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, S. The Interactive Effect of Authentic Leadership and Leader Competency on Followers’ Job Performance: The Mediating Role of Work Engagement. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 153, 763–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simsarian Webber, S. Leadership and trust facilitating cross-functional team success. J. Manag. Dev. 2002, 21, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitektine, A. Toward a Theory of Social Judgments of Organizations: The Case of Legitimacy, Reputation, and Status. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2011, 36, 151–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Graebner, M.E.; Sonenshein, S. Grand Challenges and Inductive Methods: Rigor without Rigor Mortis. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 59, 1113–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Dust, S.B.; Xu, M.; Ji, Y. Leader–follower risk orientation incongruence, intellectual stimulation, and creativity: A configurational approach. Pers. Psychol. 2021, 74, 143–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, M.; Chang, C.H.; Shi, J.; Zhou, L.; Shao, R. Work-family conflict, emotional exhaustion, and displaced ag- gression toward others: The moderating roles of workplace interpersonal conflict and perceived managerial family support. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 793–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Back-Translation for Cross-Cultural Research. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1970, 1, 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.; Farh, J.L. Developments in understanding Chinese leadership: Paternalism and its elaborations, moderations, and alternatives. In Oxford Handbook of Chinese Psychology; Bond, M., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010; pp. 599–622. [Google Scholar]

- Cicero, L.; Pierro, A.; Van Knippenberg, D. Leadership and Uncertainty: How Role Ambiguity Affects the Relationship between Leader Group Prototypicality and Leadership Effectiveness. Brit. J. Manag. 2010, 21, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methot, J.R.; Lepine, J.A.; Podsakoff, N.P.; Christian, J.S. Are Workplace Friendships a Mixed Blessing? Exploring Tradeoffs of Multiplex Relationships and their Associations with Job Performance. Pers. Psychol. 2016, 69, 311–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, N.J.; Meyer, J.P. Organizational Socialization Tactics: A Longitudinal Analysis of Links to Newcomers’ Commitment and Role Orientation. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 847–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farh, J.; Hackett, R.D.; Liang, J. Individual-Level Cultural Values as Moderators of Perceived Organizational Support–Employee Outcome Relationships in China: Comparing the Effects of Power Distance and Traditionality. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 715–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.C.; Davis, J.H. The effect of the performance appraisal system on trust for management: A field quasi-experiment. J. Appl. Psychol. 1999, 1, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, B.; Muthén, L. Mplus. In Handbook of Item Response Theory; Chapman and Hall/CRC: London, UK, 2017; pp. 507–518. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Selig, J.P. Advantages of Monte Carlo Confidence Intervals for Indirect Effects. Commun. Methods Meas. 2012, 6, 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, D.A.; Gavin, M.B. Centering Decisions in Hierarchical Linear Models: Implications for Research in Organizations. J. Manag. 1998, 24, 623–641. [Google Scholar]

- Selig, J.P.; Preacher, K.J. Monte Carlo method for assessing mediation: An interactive tool for creating confidence intervals. for indirect effects, 2008 [Computer software].

- Edelman, P.J.; van Knippenberg, D. Training Leader Emotion Regulation and Leadership Effectiveness. J. Bus. Psychol. 2017, 32, 747–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Xu, E.; Chiu, W.; Lam, C.; Farh, J. When Authoritarian Leaders Outperform Transformational Leaders: Firm Performance in a Harsh Economic Environment. Acad. Manag. Discov. 2015, 1, 180–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, W.; Chou, L.; Cheng, B.; Jen, C. Juan-Cjiuan and Shang-Yan? The components of authoritarian leaderships and their interation effects with benevolence on psychological empowerment. Indig. Psychol. Res. Chin. Soc. 2010, 34, 223–284. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, B.; Chou, L.; Huang, M.; Farh, L.J.L.; Peng, S. A triad model of paternalistic leadership: Evidence from business organizations in Mainland China. Indig. Psychol. Res. Chin. Soc. 2003, 20, 209–250. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.; Chiang, J.T.; Tsai, C.; Lin, T.; Cheng, B. Gender makes the difference: The moderating role of leader gender on the relationship between leadership styles and subordinate performance. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2013, 122, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smither, J.W.; London, M.; Reilly, R.R. Does performance improve following multisource feedback? A theoretical model, meta-analysis, and review of empirical findings. Pers. Psychol. 2005, 58, 33–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age (T1) | 36.58 | 9.89 | |||||||||||

| 2. Gender (T1) | 0.73 | 0.45 | −0.004 | ||||||||||

| 3. Education (T1) | 13.84 | 2.82 | −0.44 ** | 0.08 | |||||||||

| 4. Dyadic tenure (T1) | 3.69 | 2.96 | 0.21 ** | −0.18 ** | 0.07 | ||||||||

| 5. Power distance orientation (T1) | 3.96 | 1.39 | 0.04 | 0.27 ** | 0.10 | −0.01 | (0.92) | ||||||

| 6. Leader integrity evaluation (T2) | 5.70 | 1.18 | 0.09 | −0.04 | −0.22 ** | −0.07 | 0.06 | (0.94) | |||||

| 7. Authoritarian leadership (T1) | 3.07 | 0.77 | 0.05 | 0.12 * | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.22 ** | −0.06 | (0.89) | ||||

| 8. Leader capability (T2) | 5.82 | 1.12 | 0.06 | −0.18 ** | −0.19 ** | −0.004 | −0.12 * | 0.55 ** | −0.11 * | (0.91) | |||

| 9. Leader effectiveness (T2) | 5.64 | 1.26 | 0.004 | −0.30 ** | −0.20 ** | 0.06 | −0.34 ** | 0.24 ** | −0.20 ** | 0.45 ** | (0.96) | ||

| 10. Task performance supervisor (T2) | 5.75 | 1.06 | 0.05 | −0.33 ** | −0.08 | 0.18 ** | −0.30 ** | 0.16 ** | −0.26 ** | 0.27 ** | 0.54 ** | (0.90) | |

| 11. Affective organizational commitment (T3) | 5.04 | 1.25 | 0.09 | −0.28 ** | −0.21 ** | 0.01 | −0.30 ** | 0.22 ** | −0.13 * | 0.36 ** | 0.64 ** | 0.40 ** | (0.94) |

| Variables | Leader Effectiveness | Task Performance | Affective Organizational Commitment | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est. (SE) | Est. (SE) | Est. (SE) | Est. (SE) | Est. (SE) | Est. (SE) | |

| Intercepts | 4.42 ** (0.58) | 4.52 ** (0.58) | 4.98 ** (0.48) | 5.01 ** (0.47) | 3.88 ** (0.48) | 3.95 ** (0.47) |

| Controls | ||||||

| Age | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.004 (0.01) | 0.00 (0.01) | 0.004 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) |

| Gender | −0.18 (0.14) | −0.19 (0.13) | −0.08 (0.21) | −0.01 (0.19) | −0.24 (0.21) | −0.14 (0.18) |

| Education | −0.02 (0.02) | −0.01 (0.02) | 0.01 (0.02) | 0.01(0.02) | −0.01 (0.03) | 0.003(0.03) |

| Dyadic tenure | −0.00 (0.03) | 0.01 (0.03) | 0.03 (0.02) | 0.03 (0.02) | −0.04 (0.03) | −0.03 (0.02) |

| Power distance orientation | 0.01 (0.06) | 0.01 (0.05) | −0.02 (0.04) | −0.02 (0.04) | −0.05 (0.06) | −0.06 (0.06) |

| Leader integrity evaluation | 0.21 * (0.09) | 0.20 * (0.09) | 0.14 (0.08) | 0.06 (0.06) | 0.20 * (0.08) | 0.08 (0.06) |

| Independent Variables | ||||||

| Authoritarian leadership (AL) | −0.15 (0.08) | −0.15 * (0.08) | −0.27 ** (0.08) | −0.22 ** (0.08) | 0.08 (0.10) | 0.17 (0.09) |

| Leader capability (LC) | 0.37 ** (0.10) | 0.31 ** (0.08) | 0.10 (0.08) | −0.03 (0.06) | 0.22 ** (0.08) | 0.00 (0.09) |

| Moderation Effect | ||||||

| AL * LC | 0.31 * (0.12) | |||||

| Mediation Effect | ||||||

| Leadership effectiveness | 0.36 ** (0.08) | 0.58 ** (0.11) | ||||

| Residual Variance | 0.48 ** (0.14) | 0.53 ** (0.14) | 0.44 ** (0.10) | 0.45 ** (0.10) | 0.28 * (0.13) | 0.33 ** (0.13) |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.24 | 0.27 | 0.14 | 0.21 | 0.14 | 0.30 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, Q.; Zhang, K.; Wang, Y.; Bodla, A.A.; Zhu, D. When Is Authoritarian Leadership Less Detrimental? The Role of Leader Capability. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 707. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010707

Huang Q, Zhang K, Wang Y, Bodla AA, Zhu D. When Is Authoritarian Leadership Less Detrimental? The Role of Leader Capability. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(1):707. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010707

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Qiufeng, Kaili Zhang, Yanqun Wang, Ali Ahmad Bodla, and Duogang Zhu. 2023. "When Is Authoritarian Leadership Less Detrimental? The Role of Leader Capability" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 1: 707. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010707

APA StyleHuang, Q., Zhang, K., Wang, Y., Bodla, A. A., & Zhu, D. (2023). When Is Authoritarian Leadership Less Detrimental? The Role of Leader Capability. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 707. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010707