Forgiveness and Flourishing: The Mediating and Moderating Role of Self-Compassion

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Forgiveness and Psychological Well-Being

1.2. Self-Compassion as a Mediator or a Moderator

1.3. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Power Analysis

2.2. Participants

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Forgiveness

2.3.2. Self-Compassion

2.3.3. Flourishing

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

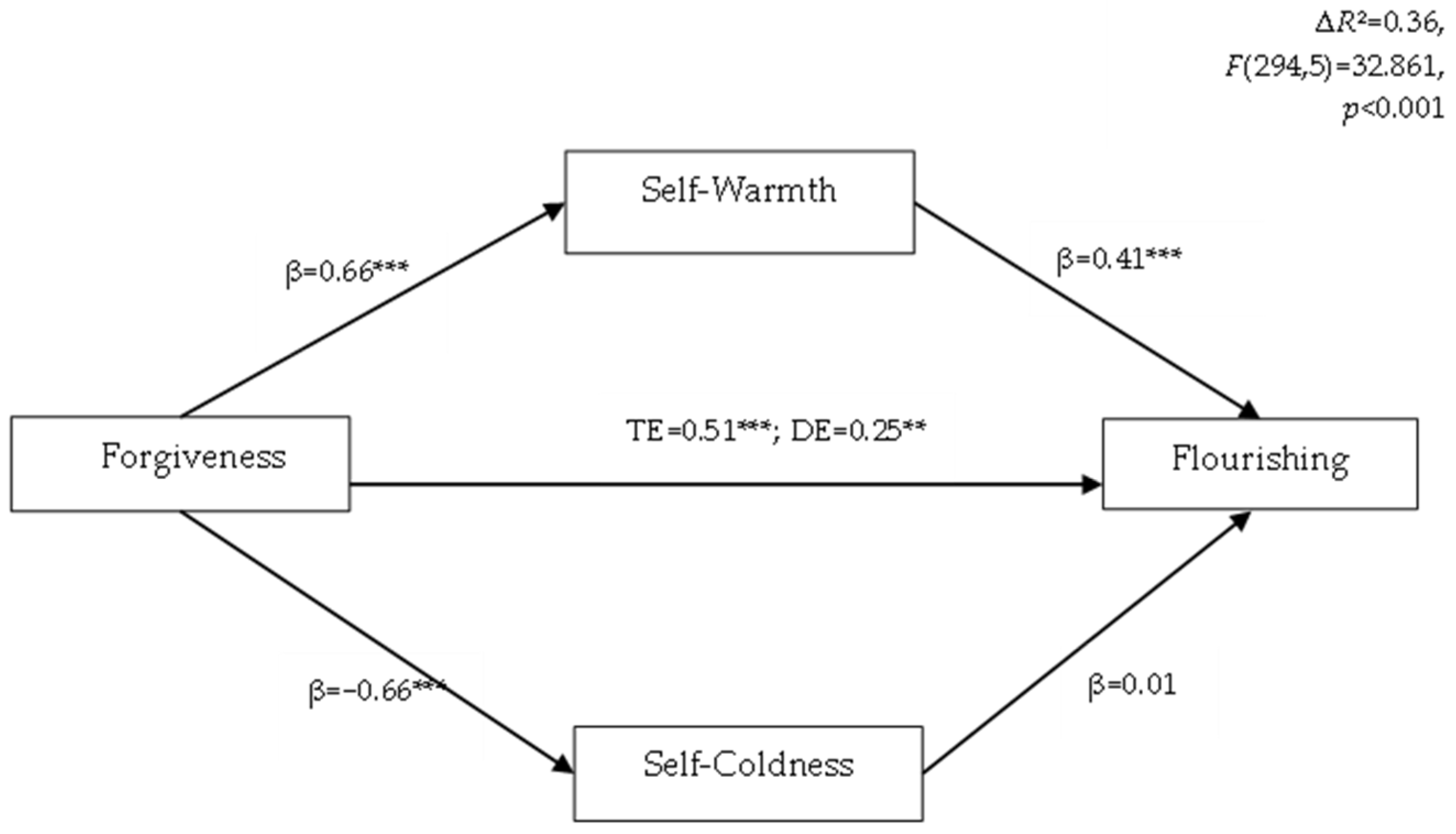

3.2. Mediational Analyses

3.3. Moderating Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Keyes, C. The Mental Health Continuum: From Languishing to Flourishing in Life. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2002, 43, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E.; Wirtz, D.; Biswas-Diener, R.; Tov, W.; Kim-Prieto, C.; Choi, D.W.; Oishi, S. New measures of well-being. In Assessing Well-Being; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 247–266. [Google Scholar]

- Eaton, J.; Ward Struthers, C.; Santelli, A.G. Dispositional and state forgiveness: The role of self-esteem, need for structure, and narcissism. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2006, 41, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, L.Y.; Snyder, C.R.; Hoffman, L.; Michael, S.T.; Rasmussen, H.N.; Billings, L.S.; Heinze, L.; Neufeld, J.E.; Shorey, H.S.; Roberts, J.C.; et al. Dispositional Forgiveness of Self, Others, and Situations. J. Pers. 2005, 73, 313–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCullough, M.E.; Hoyt, W.T. Transgression-Related Motivational Dispositions: Personality Substrates of Forgiveness and their Links to the Big Five. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2002, 28, 1556–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strelan, P. The stress-and-coping model of forgiveness: Theory, research, and the potential of dyadic coping. In Handbook of Forgiveness, 2nd ed.; Worthington, E., Jr., Wade, N.G., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 63–73. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer Publishing Company: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Toussaint, L.; Worthington, E.L.; Webb, J.R.; Wilson, C.; Williams, D.R. Forgiveness in human flourishing. In Human Flourishing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; p. 117. [Google Scholar]

- Toussaint, L.; Friedman, P. Forgiveness, Gratitude, and Well-Being: The Mediating Role of Affect and Beliefs. J. Happiness Stud. 2008, 10, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, P.L.; Heffeman, M.E.; Allemand, M. Forgiveness and subjective well-being: Discussing mechanisms, contexts, and rationales. In Forgiveness and Health: Scientific Evidence and Theories Relating Forgiveness to Better Health; Toussaint, L.L., Worthington, E.L., Jr., Williams, D.R., Eds.; Springer Science + Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L. The broaden–and–build theory of positive emotions. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 2004, 359, 1367–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skalski, S.B.; Konaszewski, K.; Niesiobędzka, M.; Gladysh, O.; Toussaint, L.L.; Surzykiewicz, J. Anger toward God and well-being in Ukrainian war refugees: The serial mediating influence of faith maturity and decisional forgiveness. 2022; preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaleta, K.; Mróz, J. Forgiveness and life satisfaction across different age groups in adults. Pers. Individ Differ. 2018, 120, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Chen, J.; Yu, X.; Sang, J. Mediator Roles of Interpersonal Forgiveness and Self-Forgiveness between Self-Esteem and Subjective well-Being. Curr. Psychol. 2017, 36, 585–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bono, G.; McCullough, M.E.; Root, L.M. Forgiveness, feeling connected to others, and well-being: Two longitudinal studies. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2008, 34, 182–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K.D. Self-Compassion, Self-Esteem, and Well-Being. Soc. Pers. Psychol. Compass. 2011, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brophy, K.; Brähler, E.; Hinz, A.; Schmidt, S.; Körner, A. The role of self-compassion in the relationship between attachment, depression, and quality of life. J. Affect Disord. 2020, 260, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Kou, Y. Self-compassion and life satisfaction: The mediating role of hope. Pers. Individ Differ. 2016, 98, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, M.; Vogt, F.; Marks, E. Dispositional Mindfulness, Gratitude and Self-Compassion: Factors Affecting Tinnitus Distress. Mindfulness 2021, 12, 1002–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sünbül, Z.A.; Güneri, O.Y. The relationship between mindfulness and resilience: The mediating role of self compassion and emotion regulation in a sample of underprivileged Turkish adolescents. Pers. Individ Differ. 2019, 139, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, M.; Yap, K.; Scott, N.; Einstein, D.A.; Ciarrochi, J. Self-compassion moderates the perfectionism and depression link in both adolescence and adulthood. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinger, J.M.; Whisman, M.A. Does Self-Compassion Moderate the Cross-Sectional Association Between Life Stress and Depressive Symptoms? Mindfulness 2021, 12, 889–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D.A.; Caswell, H.L.; Eccles, F.J.R. Self-compassion and depression, anxiety, and resilience in adults with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2019, 90, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Wang, W.; Wu, X. The mediating role of rumination in the relation between self-compassion, posttraumatic stress disorder, and posttraumatic growth among adolescents after the Jiuzhaigou earthquake. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K.D.; Hsieh, Y.P.; Dejitterat, K. Self-compassion, Achievement Goals, and Coping with Academic Failure. Self Identity 2005, 4, 263–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satake, Y.; Arao, H. Self-compassion mediates the association between conflict about ability to practice end-of-life care and burnout in emergency nurses. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2020, 53, 100917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahm, K.A.; Meyer, E.C.; Neff, K.D.; Kimbrel, N.A.; Gulliver, S.B.; Morissette, S.B. Mindfulness, Self-Compassion, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms, and Functional Disability in U.S. Iraq and Afghanistan War Veterans. J. Trauma Stress. 2015, 28, 460–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maheux, A.; Price, M. The indirect effect of social support on post-trauma psychopathology via self-compassion. Pers. Individ Differ. 2016, 88, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voci, A.; Veneziani, C.; Fuochi, G. Relating Mindfulness, Heartfulness, and Psychological Well-Being: The Role of Self-Compassion and Gratitude. Mindfulness 2019, 10, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. Conservation of Resources and Disaster in Cultural Context: The Caravans and Passageways for Resources. Psychiatry 2012, 75, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakic, H.; Ajdukovic, D. Resilience after natural disasters: The process of harnessing resources in communities differentially exposed to a flood. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2021, 12, 1891733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiner, C.; Scharmer, C.; Zon, C.; Anderson, D. The moderating role of self-compassion on the relationship between emotion-focused impulsivity and dietary restraint in a diverse undergraduate sample. Eat Behav. 2022, 46, 101650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.L. Comparison of psychological capital, self-compassion, and mental health between with overseas Chinese students and Taiwanese students in the Taiwan. Pers. Individ Differ. 2021, 183, 111131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, M.S. Relation Between Lack of Forgiveness and Depression: The Moderating Effect of Self-Compassion. Psychol. Rep. 2016, 119, 573–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Chi, P.; Zeng, X.; Lin, X.; Du, H. Roles of Anger and Rumination in the Relationship Between Self-Compassion and Forgiveness. Mindfulness 2018, 10, 272–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahimdanesh, F.; Noferesti, A.; Tavakol, K. Self-Compassion and Forgiveness: Major Predictors of Marital Satisfaction in Young Couples. Am. J. Fam. Ther. 2020, 48, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.G.; Buchner, A. G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neff, K.D. The Development and Validation of a Scale to Measure Self-Compassion. Self Identity 2003, 2, 223–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Maesschalck, R.; Jouan-Rimbaud, D.; Massart, D.L. The mahalanobis distance. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2000, 50, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guliford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mak, W.W.; Chio, F.H.; Chong, K.S.; Law, R.W. From mindfulness to personal recovery: The mediating roles of self-warmth, psychological flexibility, and valued living. Mindfulness 2021, 12, 994–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Yang, Y.; Wang, G.; Wang, H.; Feng, D. Effects of Perceived Stigma on Depressive Symptoms and Demoralization in Maintenance Hemodialysis Patients: Self-warmth and Self-coldness as Mediators. Mindfulness 2022, 13, 3058–3069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worthington, E.L. Understanding forgiveness of other people: Definitions, theories, and processes. In Handbook of Forgiveness; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 11–21. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, P. Introducing compassion-focused therapy. Adv. Psychiatr. Treat. 2009, 15, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arch, J.J.; Brown, K.W.; Dean, D.J.; Landy, L.N.; Brown, K.D.; Laudenslager, M.L. Self-compassion training modulates alpha-amylase, heart rate variability, and subjective responses to social evaluative threat in women. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2014, 42, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, S.Y.; Mak, W.W.; Chio, F.H.; Law, R.W. The mediating role of self-compassion between mindfulness and compassion fatigue among therapists in Hong Kong. Mindfulness 2017, 8, 460–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Lu, M.; Wang, G.; Wang, H.; Feng, D. The Effect of Attachment Style on Posttraumatic Growth in Maintenance Hemodialysis Patients: The Mediating Roles of Self-Warmth and Self-Coldness. Mindfulness 2022, 13, 637–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, E.C.; Yu, T.; Najarian, A.S.M.; Wright, K.M.; Chen, W.; Chang, O.D.; Hirsch, J.K. Understanding the association between negative life events and suicidal risk in college students: Examining self-compassion as a potential mediator. J. Clin. Psych. 2017, 73, 745–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ștefan, C.A. Self-compassion as mediator between coping and social anxiety in late adolescence: A longitudinal analysis. J. Adolesc. 2019, 76, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yar, K.; Francis, A.J.; Schuster, S.; Potter, R.F. Self-compassion mediates the relationship between parentalcriticism and social anxiety. Int. J. Psychol. Psychol. Ther. 2014, 14, 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Scheibner, H.J.; Daniels, A.; Guendelman, S.; Utz, F.; Bermpohl, F. Self-compassion mediates the relationship between mindfulness and borderline personality disorder symptoms. J. Pers. Disord. 2018, 32, 838–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carreiras, D.; Cunha, M.; Castilho, P. Which self-compassion components mediate the relationship between adverse experiences in childhood and borderline features in adolescents? Self-compassion in adolescents. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2021, 19, 847–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K.D.; Germer, C.K. A pilot study and randomized controlled trial of the mindful self-compassion program. J. Clin. Psych. 2013, 69, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Forgiveness | - | ||||||||||

| 2. | Self-kindness | 0.628 ** | - | |||||||||

| 3. | Common humanity | 0.479 ** | 0.605 ** | - | ||||||||

| 4. | Mindfulness | 0.555 ** | 0.711 ** | 0.534 ** | - | |||||||

| 5. | Self-warmth | 0.653 ** | 0.927 ** | 0.804 ** | 0.836 ** | - | ||||||

| 6. | Self-judgment | −0.593 ** | −0.594 ** | −0.340 ** | −0.405 ** | −0.545 ** | - | |||||

| 7. | Isolation | −0.566 ** | −0.434 ** | −0.355 ** | −0.408 ** | −0.465 ** | 0.577 ** | - | ||||

| 8. | Over identification | −0.586 ** | −0.513 ** | −0.406 ** | −0.458 ** | −0.544 ** | 0.725 ** | 0.671 ** | - | |||

| 9. | Self-coldness | −0.661 ** | −0.589 ** | −0.413 ** | −0.477 ** | −0.589 ** | 0.892 ** | 0.839 ** | 0.893 ** | - | ||

| 10. | Self-compassion | 0.736 ** | 0.850 ** | 0.690 ** | 0.741 ** | 0.894 ** | −0.794 ** | −727 ** | −0.799 ** | −0.881 ** | - | |

| 11. | Flourishing | 0.521 ** | 0.558 ** | 0.476 ** | 0.450 ** | 0.588 ** | −0.328 ** | −0.447 ** | −0.358 ** | −0.431 ** | 0.578 ** | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mróz, J. Forgiveness and Flourishing: The Mediating and Moderating Role of Self-Compassion. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 666. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010666

Mróz J. Forgiveness and Flourishing: The Mediating and Moderating Role of Self-Compassion. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(1):666. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010666

Chicago/Turabian StyleMróz, Justyna. 2023. "Forgiveness and Flourishing: The Mediating and Moderating Role of Self-Compassion" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 1: 666. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010666

APA StyleMróz, J. (2023). Forgiveness and Flourishing: The Mediating and Moderating Role of Self-Compassion. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 666. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010666