Understanding the Impact of Environmentally Specific Servant Leadership on Employees’ Pro-Environmental Behaviors in the Workplace: Based on the Proactive Motivation Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

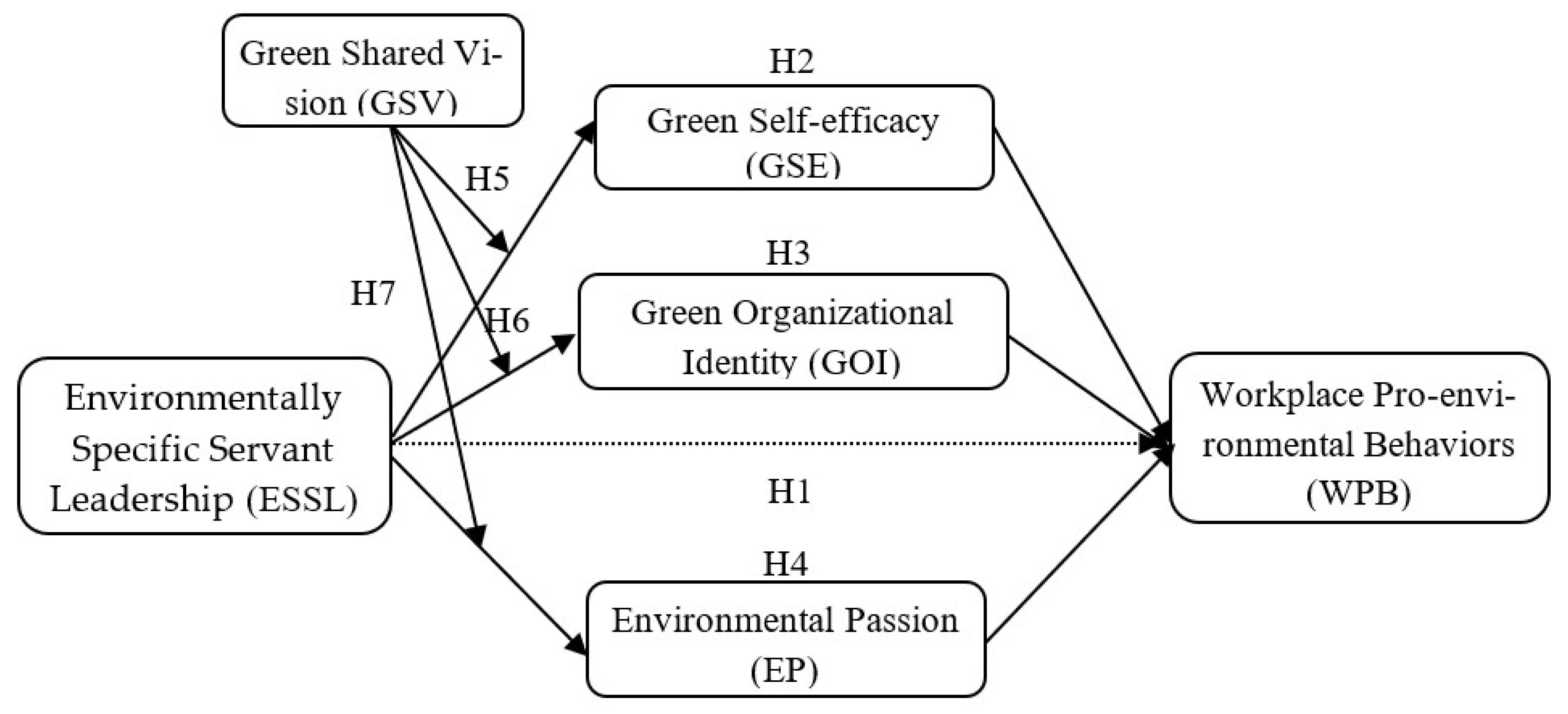

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Proactive Motivation Model

2.2. Workplace Pro-Environmental Behavior

- Individual employee factors. Employees’ values [17,54], attitude and beliefs [18], emotions [19], and motivation [55] significantly affected WPB. The values of employees determine their environmental attitudes and beliefs and other personal cognitive factors, which in turn guide employees to change their thinking, and promote the generation of controlled and autonomous environmental protection motives, so as to be restrained by pressure or motivated to participate in pro-environmental behaviors [56,57].

- External situational factors. The external contextual influencing factors of WPB are mainly divided into interpersonal [15,20], team [15], and organizational [21]. First, for the interpersonal level, WPB is reinforced by interpersonal dynamics among leaders and colleagues, including leaders imposing expectations on employees and rolling out green initiatives, open discussions of environmental sustainability among colleagues, and sharing of environmental knowledge to shape workplace interactions [15,20,27,58]. Second, for the team level, team norms and team green work atmosphere will transform corporate environmental protection policies into behavioral norms that reward and support employees and motivate employees to adopt pro-environmental behaviors [15,58]. Third, for the organizational level, corporate green human resource management and social responsibility provide employees with support situations including environmental knowledge and resources, so that employees can generate and strengthen environmental motivation and adopt pro-environmental behaviors [3,28,59,60]. In addition, the rules, regulations, and job descriptions of the enterprise restrict employees’ behaviors in the form of mandatory tasks, while the supervisor support and green internal culture in the organization will help improve employees’ autonomy. These constraints in the external context of the organization will affect employees’ beliefs and significantly influence their pro-environmental behaviors [23,24].

2.3. Environmentally Specific Servant Leadership and Workplace Pro-Environmental Behavior

2.3.1. Environmentally Specific Servant Leadership

2.3.2. The Relationship between Environmentally Specific Servant Leadership and Workplace Pro-Environmental Behavior

2.4. “Can Do” and Green Self-Efficacy as a Mediator

2.4.1. Green Self-Efficacy

2.4.2. Environmentally Specific Servant Leadership and Green Self-Efficacy

2.4.3. Green Self-Efficacy and Workplace Pro-Environmental Behavior

2.4.4. The Mediating Role of Green Self-Efficacy

2.5. “Reason to” and Green Organizational Identity as a Mediator

2.5.1. Green Organizational Identity

2.5.2. Environmentally Specific Servant Leadership and Green Organizational Identity

2.5.3. Green Organizational Identity and Workplace Pro-Environmental Behavior

2.5.4. The Mediating Role of Green Organizational Identity

2.6. “Energized to” and Environmental Passion as a Mediator

2.6.1. Environmental Passion

2.6.2. Environmentally Specific Servant Leadership and Environmental Passion

2.6.3. Environmental Passion and Workplace Pro-Environmental Behavior

2.6.4. The Mediating Role of Environmental Passion

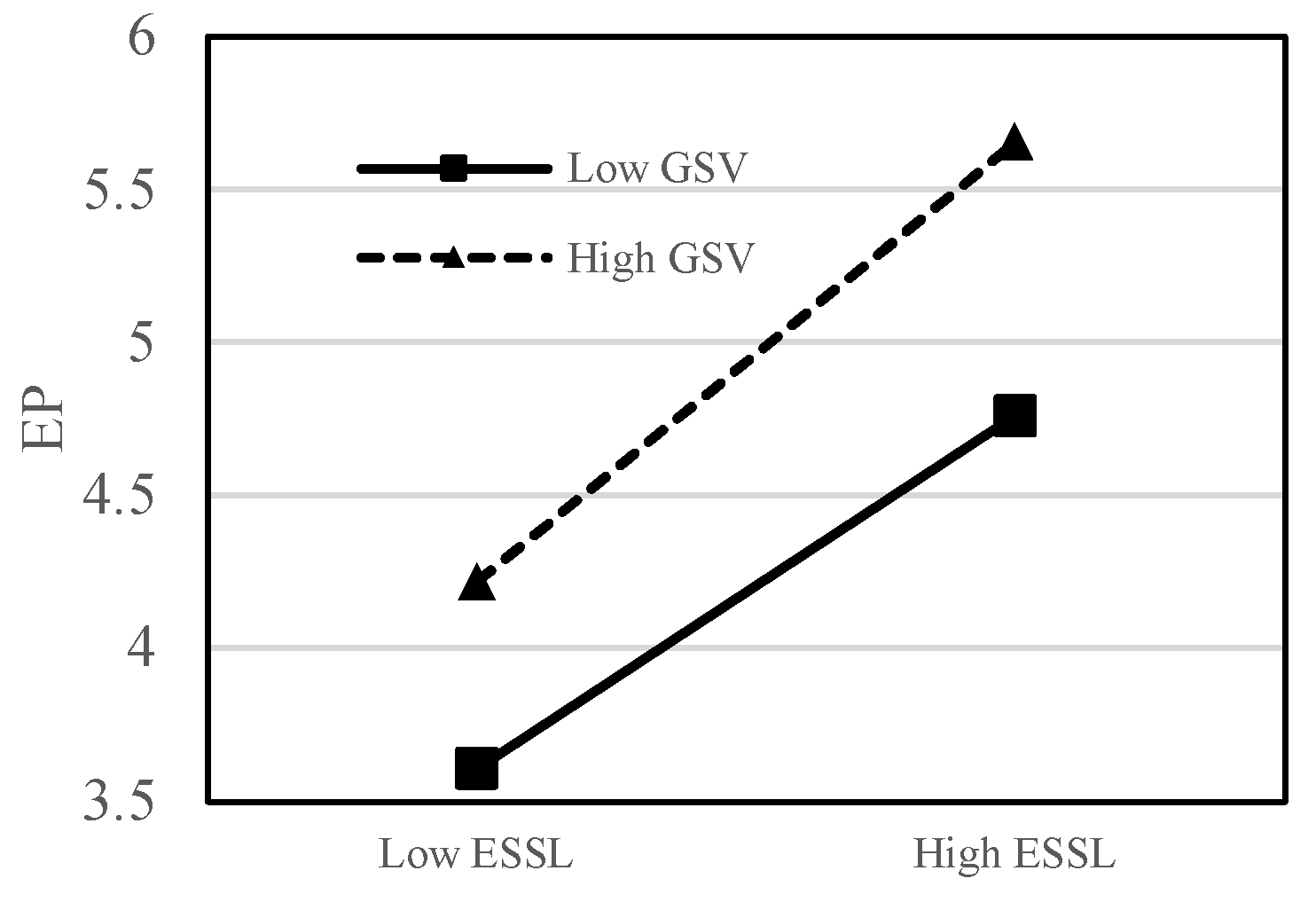

2.7. The Moderating Role of Green Shared Vision

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Sample Description

3.2. Variable Measurement

- Environmentally specific servant leadership (ESSL): The measurement items refer to the Environmental Service Leadership Scale adapted by Luu [66], which is directly scored by employees to their superiors, with a total of 12 items. Example items include “My supervisor cares about my eco-initiatives” and “My supervisor emphasizes the importance of contributing to the environmental improvement”.

- Workplace pro-environmental behaviors (WPB): The measurement items refer to the Employee Pro-environmental Behavior Scale of Robertson and Barling [38], with a total of 7 items. Example items include “I print double sided whenever possible” and “I put compostable items in the compost bin”.

- Green self-efficacy (GSE): The measurement items refer to the Green Self-Efficacy Scale of Chen and Chang [26], with a total of 6 items. Example items include “We feel we can succeed in accomplishing environmental ideas” and “We can achieve most of environmental goals”.

- Green organizational identity (GOI): The measurement items refer to the Green Organizational Identity Scale of Chen [37], with a total of 6 items. Example items include “The company’s top managers, middle managers, and employees have a strong sense of the company’s history about environmental management and protection” and “The company’s top managers, middle managers, and employees have a sense of pride in the company’s environmental goals and missions”.

- Environmental passion (EP): The measurement items refer to the Environmental Passion Scale of Robertson and Barling [38], with a total of 10 items. Example items include “I am passionate about the environment” and “I enjoy practicing environmental-friendly behaviors”.

- Green shared vision (GSV): The measurement items refer to the Green Shared Vision Scale of Chen [26], with a total of 4 items. Example items include “There is commonality of environmental goals in the company” and “There is total agreement on the company’s strategic environmental direction”.

3.3. Common Method Variance

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Reliability and Validity

4.2. Descriptive Statistics Analysis

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

4.3.1. Principal Effect Testing

4.3.2. Mediating Effect Testing

4.3.3. Moderating Effect Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Survey Items

| Environmentally Specific Servant Leadership (ESSL) |

|---|

| ESSL is measured to what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statements on a 5-point Likert-scale (5-Strongly Agree, 1-Strongly Disagree) |

| ESSL1-My supervisor cares about my eco-initiatives. |

| ESSL2-My supervisor emphasizes the importance of contributing to the environmental improvement. |

| ESSL3-My supervisor is involved in environmental activities. |

| ESSL4-I am encouraged by my supervisor to volunteer in environmental activities. |

| ESSL5-My supervisor has a thorough understanding of our company and its environmental goals. |

| ESSL6-My supervisor encourages me to contribute eco-initiatives. |

| ESSL7-My supervisor gives me the freedom to handle environmental problems in the way that I feel is best. |

| ESSL8-My supervisor does what she/he can do to realize my eco-initiatives. |

| ESSL9-My supervisor holds high environmental standards. |

| ESSL10-My supervisor always displays green behaviors. |

| ESSL11-My supervisor would not compromise environmental principles in order to achieve success. |

| ESSL12-My supervisor values environmental performance more than profits. |

| Workplace Pro-environmental Behavior (WPB) |

| WPB is measured to what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statements on a 5-point Likert-scale (5-Strongly Agree, 1-Strongly Disagree) |

| WPB1-I print double sided whenever possible. |

| WPB2-I put compostable items in the compost bin. |

| WPB3-I put recyclable material (e.g., cans, paper, bottles, batteries) in the recycling bins. |

| WPB4-I bring reusable eating utensils to work (e.g., travel coffee mug, water bottle, reusable containers, reusable cutlery). |

| WPB5-I turn lights off when not in use. |

| WPB6-I take part in environmentally friendly programs (e.g., bike/walk to work day, bring your own local lunch day). |

| WPB7-I make suggestions about environmentally friendly practices to managers and/or environmental committees, in an effort to increase my organization’s environmental performance. |

| Green Self-efficacy (GSE) |

| GSE is measured to what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statements on a 5-point Likert-scale (5-Strongly Agree, 1-Strongly Disagree) |

| GSE1-We feel we can succeed in accomplishing environmental ideas. |

| GSE2-We can achieve most of environmental goals. |

| GSE3-We feel competent to deal effectively with environmental tasks. |

| GSE4-We can perform effectively on environmental missions. |

| GSE5-We can overcome environmental problems. |

| GSE6-We could find out creative solutions to environmental problems. |

| Green Organizational Identity (GOI) |

| GOI is measured to what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statements on a 5-point Likert-scale (5-Strongly Agree, 1-Strongly Disagree) |

| GOI1-The company’s top managers, middle managers, and employees have a strong sense of the company’s history about environmental management and protection. |

| GOI2-The company’s top managers, middle managers, and employees have a sense of pride in the company’s environmental goals and missions. |

| GOI3-The company’s top managers, middle managers, and employees feel that the company has carved out a significant position with respect to environmental management and protection. |

| GOI4-The company’s top managers, middle managers, and employees feel that the company have formulated a well-defined set of environmental goals and missions. |

| GOI5-The company’s top managers, middle managers, and employees are knowledgeable about the company’s environmental traditions and cultures. |

| GOI6-The company’s top managers, middle managers, and employees identify strongly with the company’s actions with respect to environmental management and protection. |

| Environmental Passion (EP) |

| EP is measured to what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statements on a 5-point Likert-scale (5-Strongly Agree, 1-Strongly Disagree) |

| EP1-I am passionate about the environment. |

| EP2-I enjoy practicing environmentally friendly behaviors. |

| EP3-I enjoy engaging in environmentally friendly behaviors. |

| EP4-I take pride in helping the environment. |

| EP5-I enthusiastically discuss environmental issues with others. |

| EP6-I get pleasure from taking care of the environment. |

| EP7-I passionately encourage others to be more environmentally responsible. |

| EP8-I am a volunteered member of an environmental group. |

| EP9-I have voluntarily donated time or money to help the environment in some way. |

| EP10-I feel strongly about my environmental values. |

| Green Shared Vision (GSV) |

| GSV is measured to what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statements on a 5-point Likert-scale (5-Strongly Agree, 1-Strongly Disagree) |

| GSV1-There is commonality of environmental goals in the company. |

| GSV2-There is total agreement on the company’s strategic environmental direction. |

| GSV3-All members in the company are committed to the environmental strategies of the company. |

| GSV4-The company’s employees are enthusiastic about the collective environmental mission of the company. |

References

- Pham, N.M.; Huynh, T.L.D.; Nasir, M.A. Environmental consequences of population, affluence and technological progress for European countries: A Malthusian view. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 260, 1101432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Y.; Liu, Y.; Han, C.; Gao, Y.; Lan, Y. How does environmentally specific servant leadership fuel employees’ low-carbon behavior? The role of environmental self-accountability and power distance orientation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, X.; Ahmad, N.; Sial, M.S.; Cherian, J.; Han, H. CSR and organizational performance: The role of pro-environmental behavior and personal values. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022; online. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, Z.; Álvarez-Otero, S.; Sulaiman, M.A.B.A.; Sial, M.S.; Ahmad, N.; Scholz, M.; Omhand, K. Achieving organizational social sustainability through electronic performance appraisal systems: The moderating influence of transformational leadership. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Cherian, J.; Ahmad, N.; Scholz, M.; Samad, S. Conceptualizing the role of target-specific environmental transformational leadership between corporate social responsibility and pro-environmental behaviors of hospital employees. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darvishmotevali, M.; Altinay, L. Green HRM, environmental awareness and green behaviors: The moderating role of servant leadership. Tour. Manag. 2022, 88, 104401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, J.; Kohlová, M.B. The COVID-19 crisis does not diminish environmental motivation: Evidence from two panel studies of decision making and self-reported pro-environmental behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 80, 101761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, P.; Assaker, G. COVID-19’s effects on future pro-environmental traveler behavior: An empirical examination using norm activation, economic sacrifices, and risk perception theories. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 30, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisar, Q.A.; Haider, S.; Ali, F.; Jamshed, S.; Ryu, K.; Gill, S.S. Green human resource management practices and environmental performance in Malaysian green hotels: The role of green intellectual capital and pro-environmental behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 311, 127504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suganthi, L. Examining the relationship between corporate social responsibility, performance, employees’ pro-environmental behavior at work with green practices as mediator. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 232, 739–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferenc, M. Environmental education policy of schools and socioeconomic background affect environmental attitudes and pro-environmental behavior of secondary school students. Environ. Educ. Res. 2022, 28, 169–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Tian, J.; Liu, H. The roles of mental construal level theory in the promotion of university students’ pro-environmental behaviors. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 735837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.S.; Terason, S. Encouraging pro-environmental behavior in university employees: An approach toward environmental sustainability as moderated by green organizational culture. J. Community Psychol. 2021, 50, 1454–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, A.; Kim, Y.; Han, K.; Jackson, S.E.; Ployhart, R.E. Multilevel influences on voluntary workplace green behavior: Individual differences, leader behavior, and coworker advocacy. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 1335–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, J.; Shen, J.; Deng, X. Effects of green HRM practices on employee workplace green behavior: The role of psychological green climate and employee green values. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 56, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; UlDurar, S.; Akhtar, M.N.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, L. How does responsible leadership affect employees’ voluntary workplace green behaviors? A multilevel dual process model of voluntary workplace green behaviors. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 296, 113205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Zhang, J.; Li, J. The relationship between pro-environmental attitude and employee green behavior: The role of motivational states and green work climate perceptions. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 27, 7341–7352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Zou, J.; Chen, H.; Long, R. Promotion or inhibition? Moral norms, anticipated emotion and employee’s pro-environmental behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Gao, X.; Cai, W.; Jiang, L. How environmental leadership boosts employees’ green innovation behavior? A moderated mediation model. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 689671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umrani, W.A.; Channa, N.A.; Ahmed, U.; Syed, J.; Pahi, M.H.; Ramayah, T. The laws of attraction: Role of green human resources, culture and environmental performance in the hospitality sector. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 103, 103222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouro, C.; Duarte, A.P. Organisational climate and pro-environmental behaviours at work: The mediating role of personal norms. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 635739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuriev, A.; Boiral, O.; Francoeur, V.; Paillé, P. Overcoming the barriers to pro-environmental behaviors in the workplace: A systematic review. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuriev, A.; Boiral, O.; Guillaumie, L. Evaluating determinants of employees’ pro-environmental behavioral intentions. Int. J. Manpow. 2020, 41, 1005–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrukh, M.; Ansari, N.; Raza, A.; Wu, Y.; Wang, H. Fostering employee’s pro-environmental behavior through green transformational leadership, green human resource management and environmental knowledge. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 179, 121643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H.; Yeh, S.L.; Cheng, H.I. Green shared vision and green creativity: The mediation roles of green mindfulness and green self-efficacy. Qual. Quant. 2015, 49, 1169–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, M. Environmentally specific transformational leadership and pro-environmental behavior: An empirical analysis of energy sector. Int. J. Organ. Behav. 2022; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zuo, W. Arousing employee pro-environmental behavior: A synergy effect of environmentally specific transformational leadership and green human resource management. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2022; online. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiul, M.K.; Patwary, A.K.; Panha, I.M. The role of servant leadership, self-efficacy, high performance work systems, and work engagement in increasing service-oriented behavior. J. Hosp. Market. Manag. 2022, 31, 504–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, T.; Gao, C.; Chen, F.; Zhang, L.; Li, M. Can empowering leadership promote employees’ pro-environmental behavior? Empirical analysis based on psychological distance. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 774561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patwary, A.K.; Mohd, Y.M.F.; Bah, S.D.; Ab, G.S.F.; Rahman, M.K. Examining proactive pro-environmental behaviour through green inclusive leadership and green human resource management: An empirical investigation among Malaysian hotel employees. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights, 2022; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parris, D.L.; Peachey, J.W. A systematic literature review of servant leadership theory in organizational contexts. J. Bus. Ethics. 2013, 113, 377–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, T.T. Building employees’ organizational citizenship behavior for the environment: The role of environmentally-specific servant leadership and a moderated mediation mechanism. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 31, 406–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.L.; Barling, J. Contrasting the nature and effects of environmentally specific and general transformational leadership. Leadersh. Org. Dev. J. 2017, 38, 22–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, T.T. Effects of environmentally-specific servant leadership on green performance via green climate and green crafting. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2019, 38, 925–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, T.T. Integrating green strategy and green human resource practices to trigger individual and organizational green performance: The role of environmentally-specific servant leadership. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1193–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S. Green organizational identity: Sources and consequence. Manag. Decis. 2011, 49, 384–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.L.; Barling, J. Greening organizations through leaders’ influence on employees’ pro-environmental behaviors. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 176–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H. The determinants of green product development performance: Green dynamic capabilities, green transformational leadership, and green creativity. J. Bus. Ethics. 2013, 116, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xue, J.; Li, R.; Chen, H.; Wang, T. Environmentally specific transformational leadership and employee’s pro-environmental behavior: The mediating roles of environmental passion and autonomous motivation. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Husnain, M.; Yang, H.; Ullah, S.; Abbas, J.; Zhang, R. Corporate business strategy and tax avoidance culture: Moderating role of gender diversity in an emerging economy. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 827553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alt, E.; Díez-de-Castro, E.P.; Lloréns-Montes, F.J. Linking employee stakeholders to environmental performance: The role of proactive environmental strategies and shared vision. J. Bus. Ethics. 2015, 128, 67–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B.; Cheema, S.; Javed, F. Activating employee’s pro-environmental behaviors: The role of CSR, organizational identification, and environmentally specific servant leadership. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 904–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B.; Maqsoom, A.; Shahjeha, A.; Afridi, S.A.; Nawaz, A.; Fazliani, H. Responsible leadership and employee’s proenvironmental behavior: The role of organizational commitment, green shared vision, and internal environmental locus of control. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.K.; Bindl, U.K.; Strauss, K.; Strauss, K. Making things happen: A model of proactive motivation. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 827–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.; Hsu, D.Y.; Parker, S.K. Received respect and constructive voice: The roles of proactive motivation and perspective taking. J. Manag. 2019, 47, 399–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Kim, H. The effect of socially responsible HRM on organizational citizenship behavior for the environment: A proactive motivation model. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzoli, A.; Curcuruto, M. Safety leadership and safety voices: Exploring the mediation role of proactive motivations. J. Risk Res. 2021, 24, 1368–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Zhang, W.; Qu, Y.; Wang, B.; Chen, M. The enactment of knowledge sharing: The roles of psychological availability and team psychological safety climate. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 551366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bissing-Olson, M.J.; Iyer, A.; Fielding, K.S.; Zacher, H. Relationships between daily affect and pro-environmental behavior at work: The moderating role of pro-environmental attitude. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 156–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francoeur, V.; Paillé, P.; Yuriev, A.; Boiral, O. The measurement of green workplace behaviors: A systematic review. Organ. Environ. 2019, 34, 18–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramus, C.A.; Killmer, A.B.C. Corporate greening through prosocial extrarole behaviours—A conceptual framework for employee motivation. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2007, 16, 554–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Liao, H.; Raub, S.; Han, J.H. What it takes to get proactive: An integrative multilevel model of the antecedents of personal initiative. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 687–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unsworth, K.L.; Davis, M.C.; Russell, S.V.; Bretter, C. Employee green behaviour: How organizations can help the environment. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2020, 42, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, T.A.; Zacher, H.; Ashkanasy, N.M. Organisational sustainability policies and employee green behaviour: The mediating role of work climate perceptions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robina-Ramírez, R.; Merodio, J.A.M.; McCallum, S. What role do emotions play in transforming students’ environmental behaviour at school? J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; Robertson, J.L. How and when does perceived CSR affect employees’ engagement in voluntary pro-environmental behavior? J. Bus. Ethics. 2019, 155, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.S.; Du, J.; Ali, M.; Saleem, S.; Usman, M. Interrelations between ethical leadership, green psychological climate, and organizational environmental citizenship behavior: A moderated mediation model. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrbr, A.; Dmhk, B.; Nnr, C. Green human resource management and supervisor pro-environmental behavior: The role of green work climate perceptions. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 313, 127669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, H.; Ho, J.A.; Cheah, J.H.; Mohamed, R. Promoting pro-environmental behavior through organizational identity and green organizational climate. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2022; online. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasrado, F.; Zakaria, N. Go green! exploring the organizational factors that influence self-initiated green behavior in the United Arab Emirates. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2020, 37, 823–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, T.T. Catalyzing employee ocbe in tour companies: The role of environmentally specific charismatic leadership and organizational justice for pro-environmental behaviors. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2019, 43, 682–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Jiang, L.; Cai, W.; Xu, B.; Gao, X. How can hotel employees produce workplace environmentally friendly behavior? The role of leader, corporate and coworkers. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 725170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboramadan, M.; Kundi, Y.M.; Farao, C. Examining the effects of environmentally-specific servant leadership on green work outcomes among hotel employees: The mediating role of climate for green creativity. J. Hosp. Market. Manag. 2021, 30, 929–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, T.T. Environmentally-specific servant leadership and green creativity among tourism employees: Dual mediation paths. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 86–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, T.T. Activating tourists’ citizenship behavior for the environment: The roles of CSR and frontline employees’ citizenship behavior for the environment. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1178–1203. [Google Scholar]

- Dey, M.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Mahmood, M.; Uddin, M.A.; Biswas, S.R. Ethical leadership for better sustainable performance: Role of employee values, behavior and ethical climate. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 337, 130527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, L.; Zhang, L. Does gender matter? The trickle-down effect of voluntary green behavior in organizations. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2022; online. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clercq, D.D.; Fatima, T.; Jahanzeb, S. Cronies, procrastinators, and leaders: A conservation of resources perspective on employees’ responses to organizational cronyism. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2022, 31, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2002, 6, 307–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Lyu, Y.; He, Y. Servant leadership and proactive customer service performance. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 1330–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, C.; Sting, F.J.; Schlickel, M.; Alexy, O. The ideator’s bias: How identity-induced self-efficacy drives overestimation in employee-driven process innovation. Acad. Manag. J. 2019, 62, 1498–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Zhu, Q.; Qi, G. How can green training promote employee career growth? J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 259, 120818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mughal, M.F.; Cai, S.L.; Faraz, N.A.; Ahmed, F. Environmentally specific servant leadership and employees’ pro-environmental behavior: Mediating role of green self efficacy. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2022, 15, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Liang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Song, Y.; Xing, X. The antecedent and performance of environmental managers’ proactive pollution reduction behavior in Chinese manufacturing firms: Insight from the proactive behavior theory. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 242, 327–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asad, M.; Kashif, M.; Sheikh, U.A.; Asif, M.U.; George, S.; Khan, G.H. Synergetic effect of safety culture and safety climate on safety performance in SMEs: Does transformation leadership have a moderating role. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2022, 28, 1858–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.; Powell, C.; Collett, J. Profiling hoarding within the five-factor model of personality and self-determination theory. Behav. Therapy. 2022, 53, 546–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Jiang, W.; Zhang, G.; Chu, F. Spiritual leadership on proactive workplace behavior: The role of organizational identification and psychological safety. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Q.M.; Nisar, Q.A.; Abidin, R.Z.U.; Qammar, R.; Abbass, K. Greening the workforce in higher educational institutions: The pursuance of environmental performance. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022; online. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.; Greene, P.G.; Crick, A. Does entrepreneurial self-efficacy distinguish entrepreneurs from managers? J. Bus. Ventur. 1998, 13, 295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Du, J.; Khan, M.A.S.; Jin, S.; Altaf, M.; Anwar, F.; Sharif, I. Effects of subjective norms and environmental mechanism on green purchase behavior: An extended model of theory of planned behavior. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 779629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, W.; Peng, C.; Li, J.; Zhang, S.; Cai, W.; Chen, D. The trickle-down effect of leaders’ VWGB on employees’ pro-environmental behaviors: A moderated mediation model. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 623687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, O.; Rupp, D.E.; Farooq, M. The multiple pathways through which internal and external corporate social responsibility influence organizational identification and multifoci outcomes: The moderating role of cultural and social orientations. Acad. Manag. J. 2017, 60, 954–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zientara, P.; Zamojska, A. Green organizational climates and employee pro-environmental behaviour in the hotel industry. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1142–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Ren, S.; Yu, J. Bridging the gap between corporate social responsibility and new green product success: The role of green organizational identity. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2019, 28, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruepert, A.M.; Keizer, K.; Steg, L. The relationship between corporate environmental responsibility, employees’ biospheric values and pro-environmental behaviour at work. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 54, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soewarno, N.; Tjahjadi, B.; Fithrianti, F. Green innovation strategy and green innovation: The roles of green organizational identity and environmental organizational legitimacy. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 3061–3078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.S.; Park, T.Y.; Koo, B. Identifying organizational identification as a basis for attitudes and behaviors: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 141, 1049–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Harrison, S.H.; Corley, K.G. Identification in organizations: An examination of four fundamental questions. J. Manag. 2008, 34, 325–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parida, S.; Ananthram, S.; Chan, C.; Brown, K. Green office buildings and sustainability: Does green human resource management elicit green behaviors? J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 329, 129764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koseoglu, G.; Liu, Y.; Shalley, C.E. Working with creative leaders: Exploring the relationship between supervisors’ and subordinates’ creativity. Leadersh. Q. 2017, 28, 798–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.; Hung, C. How to shape the employees’ organization sustainable green knowledge sharing: Cross-level effect of green organizational identity effect on green management behavior and performance of members. Sustainability 2021, 13, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Yu, H. Green innovation strategy and green innovation: The roles of green creativity and green organizational identity. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, M.A.; Shabbir, M.S.; Mahmood, A.; Sulaiman, M.A.B.A.; Shahid, K. Holistic human resource development model in health sector: A phenomenological approach. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2019, 20, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Chen, X.; Zou, Y.; Nie, Q. Environmentally specific transformational leadership and team pro-environmental behaviors: The roles of pro-environmental goal clarity, pro-environmental harmonious passion, and power distance. Hum. Relat. 2021, 74, 1864–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, H.M.; Cropanzano, R. Affective events theory: A theoretical discussion of the structure, causes and consequences of affective experiences at work. Res. Organ. Beh. 1996, 18, 105–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petitta, L.; Jiang, L. How emotional contagion relates to burnout: A moderated mediation model of job insecurity and group member prototypicality. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2020, 27, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallerand, R.J.; Salvy, S.J.; Mageau, G.A.; Elliot, A.J.; Denis, P.I.; Grouzet, F.M.E.; Blanchard, C. On the role of passion in performance. J. Pers. 2007, 75, 505–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.; Ma, H.; Gong, Y.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, Y. Environmental CSR and environmental citizenship behavior: The role of employees’ environmental passion and empathy. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 320, 128751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.; Kim, Y.; Han, K. A cross level investigation on the linkage between job satisfaction and voluntary workplace green behavior. J. Bus. Ethics. 2019, 159, 1199–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, S.; Xia, E.; Ali, F.; Awan, U.; Ashfaq, M. Achieving green product and process innovation through green leadership and creative engagement in manufacturing. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2022, 33, 656–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.W.; Chen, F.F.; Luan, H.D.; Chen, Y.S. Effect of green organizational identity, green shared vision, and organizational citizenship behavior for the environment on green product development performance. Sustainability 2019, 11, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantabutra, S.; Avery, G.C. The power of vision: Statements that resonate. J. Bus. Strateg. 2010, 31, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Lin, S.H.; Lin, C.H.; Hung, S.T.; Chang, C.W.; Huang, C.W. Improving green product development performance from green vision and organizational culture perspectives. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Classification | Counts | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 243 | 55.2 |

| Male | 197 | 44.8 | |

| Age | Less than 25 | 34 | 7.7 |

| 26–35 | 310 | 70.5 | |

| 36–45 | 65 | 14.8 | |

| 46 and above | 31 | 7.0 | |

| Edu | High, Primary and Secondary school | 44 | 10.0 |

| Vocational school | 67 | 15.2 | |

| Bachelor degree | 280 | 63.6 | |

| Master or PhD | 49 | 11.1 | |

| Tenure | Less than 1 year | 14 | 3.2 |

| 1–5 year | 139 | 31.6 | |

| 6–10 year | 190 | 43.2 | |

| 10 and above | 97 | 22.0 |

| Variable | Item | Factor Loading | CICT | AVE | The Square Root of AVE | Cronbach’s α | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESSL | ESSL1 | 0.837 | 0.816 | 0.604 | 0.777 | 0.947 | 0.948 |

| ESSL2 | 0.835 | 0.807 | |||||

| ESSL3 | 0.773 | 0.750 | |||||

| ESSL4 | 0.740 | 0.718 | |||||

| ESSL5 | 0.731 | 0.711 | |||||

| ESSL6 | 0.811 | 0.788 | |||||

| ESSL7 | 0.637 | 0.617 | |||||

| ESSL8 | 0.817 | 0.804 | |||||

| ESSL9 | 0.814 | 0.784 | |||||

| ESSL10 | 0.834 | 0.807 | |||||

| ESSL11 | 0.673 | 0.652 | |||||

| ESSL12 | 0.795 | 0.774 | |||||

| GSE | GSE1 | 0.786 | 0.728 | 0.551 | 0.742 | 0.879 | 0.880 |

| GSE2 | 0.745 | 0.691 | |||||

| GSE3 | 0.796 | 0.753 | |||||

| GSE4 | 0.745 | 0.675 | |||||

| GSE5 | 0.697 | 0.640 | |||||

| GSE6 | 0.676 | 0.629 | |||||

| GOI | GOI1 | 0.766 | 0.725 | 0.620 | 0.787 | 0.907 | 0.907 |

| GOI2 | 0.799 | 0.753 | |||||

| GOI3 | 0.796 | 0.746 | |||||

| GOI4 | 0.808 | 0.765 | |||||

| GOI5 | 0.755 | 0.719 | |||||

| GOI6 | 0.800 | 0.750 | |||||

| EP | EP1 | 0.756 | 0.731 | 0.609 | 0.780 | 0.937 | 0.940 |

| EP2 | 0.752 | 0.720 | |||||

| EP3 | 0.813 | 0.787 | |||||

| EP4 | 0.764 | 0.734 | |||||

| EP5 | 0.759 | 0.738 | |||||

| EP6 | 0.789 | 0.760 | |||||

| EP7 | 0.810 | 0.786 | |||||

| EP8 | 0.753 | 0.719 | |||||

| EP9 | 0.805 | 0.784 | |||||

| EP10 | 0.799 | 0.768 | |||||

| WPB | WPB1 | 0.752 | 0.715 | 0.581 | 0.762 | 0.906 | 0.906 |

| WPB2 | 0.758 | 0.723 | |||||

| WPB3 | 0.801 | 0.769 | |||||

| WPB4 | 0.683 | 0.651 | |||||

| WPB5 | 0.760 | 0.739 | |||||

| WPB6 | 0.801 | 0.742 | |||||

| WPB7 | 0.772 | 0.696 | |||||

| GSV | GSV1 | 0.674 | 0.613 | 0.526 | 0.725 | 0.812 | 0.815 |

| GSV2 | 0.658 | 0.589 | |||||

| GSV3 | 0.732 | 0.637 | |||||

| GSV4 | 0.826 | 0.703 |

| ESSL | GSE | GOI | EP | WPB | GSV | Gender | Age | Edu | Year | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESSL | 1.000 | |||||||||

| GSE | 0.723 ** | 1.000 | ||||||||

| GOI | 0.695 ** | 0.727 ** | 1.000 | |||||||

| EP | 0.739 ** | 0.641 ** | 0.641 ** | 1.000 | ||||||

| WPB | 0.735 ** | 0.664 ** | 0.665 ** | 0.749 ** | 1.000 | |||||

| GSV | 0.346 ** | 0.189 ** | 0.288 ** | 0.234 ** | 0.247 ** | 1.000 | ||||

| Gender | 0.035 | 0.041 | 0.026 | 0.079 | 0.088 | 0.004 | 1.000 | |||

| Age | 0.181 ** | 0.121 * | 0.143 ** | 0.180 ** | 0.170 ** | 0.104 * | −0.112 * | 1.000 | ||

| Edu | −0.098 * | −0.025 | −0.054 | −0.062 | −0.055 | −0.094 * | 0.108 * | −0.290 ** | 1.000 | |

| Tenure | 0.225 ** | 0.196 ** | 0.174 ** | 0.172 ** | 0.228 ** | 0.164 ** | −0.118 * | 0.664 ** | −0.208 ** | 1.000 |

| Mean | 3.807 | 4.012 | 3.876 | 3.993 | 4.102 | 4.177 | 1.450 | 2.210 | 2.760 | 2.840 |

| SD | 0.802 | 0.641 | 0.763 | 0.743 | 0.751 | 0.619 | 0.498 | 0.681 | 0.779 | 0.800 |

| GSE | GOI | EP | WPB | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | Model 9 | Model 10 | Model 11 | Model 12 | Model 13 | Model 14 | |

| Gender | 0.064 | 0.014 | 0.050 | 0.003 | 0.107 * | 0.057 | 0.119 * | 0.070 * | 0.078 * | 0.087 * | 0.041 | 0.066 * | 0.069 * | 0.044 |

| (0.181) | (0.667) | (0.295) | (0.940) | (0.025) | (0.083) | (0.012) | (0.033) | (0.030) | (0.015) | (0.201) | (0.037) | (0.027) | (0.133) | |

| Age | −0.012 | −0.046 | 0.047 | 0.015 | 0.119 | 0.085 | 0.037 | 0.003 | 0.045 | 0.007 | −0.050 | 0.016 | −0.001 | −0.035 |

| (0.857) | (0.314) | (0.462) | (0.755) | (0.063) | (0.055) | (0.557) | (0.939) | (0.356) | (0.886) | (0.247) | (0.711) | (0.982) | (0.380) | |

| Edu | 0.009 | 0.046 | −0.015 | 0.021 | −0.018 | 0.020 | −0.012 | 0.025 | −0.017 | −0.002 | 0.001 | 0.013 | 0.019 | 0.016 |

| (0.862) | (0.186) | (0.760) | (0.568) | (0.715) | (0.553) | (0.806) | (0.457) | (0.638) | (0.950) | (0.972) | (0.697) | (0.554) | (0.594) | |

| Tenure | 0.213 ** | 0.076 | 0.145 * | 0.013 | 0.102 | −0.038 | 0.215 ** | 0.078 | 0.079 | 0.122 * | 0.141 ** | 0.058 | 0.074 | 0.095 * |

| (0.001) | (0.089) | (0.022) | (0.774) | (0.105) | (0.385) | (0.001) | (0.074) | (0.102) | (0.011) | (0.001) | (0.172) | (0.074) | (0.015) | |

| ESSL | 0.719 *** | 0.691 *** | 0.732 *** | 0.716 *** | 0.521 *** | 0.513 *** | 0.386 *** | |||||||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | ||||||||

| GSE | 0.640 *** | 0.272 *** | ||||||||||||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |||||||||||||

| GOI | 0.640 *** | 0.295 *** | ||||||||||||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |||||||||||||

| EP | 0.731 *** | 0.451 *** | ||||||||||||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |||||||||||||

| R2 | 0.043 | 0.529 | 0.034 | 0.483 | 0.049 | 0.553 | 0.066 | 0.549 | 0.458 | 0.462 | 0.575 | 0.584 | 0.594 | 0.640 |

| Adj.R2 | 0.034 | 0.523 | 0.025 | 0.477 | 0.040 | 0.548 | 0.058 | 0.544 | 0.452 | 0.456 | 0.570 | 0.579 | 0.589 | 0.635 |

| F | 4.863 ** | 97.347 *** | 3.844 ** | 81.218 *** | 5.557 *** | 107.380 *** | 7.744 *** | 105.866 *** | 73.491 *** | 74.596 *** | 117.225 *** | 101.442 *** | 105.777 *** | 128.562 *** |

| (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.004) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| GSE | GOI | EP | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 15 | Model 16 | Model 17 | Model 18 | Model 19 | Model 20 | |

| Gender | 0.015 | 0.014 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.057 | 0.055 |

| (0.655) | (0.680) | (0.949) | (0.967) | (0.082) | (0.084) | |

| Age | −0.049 | −0.048 | 0.017 | 0.017 | 0.084 | 0.084 |

| (0.281) | (0.276) | (0.719) | (0.717) | (0.058) | (0.053) | |

| Edu | 0.042 | 0.047 | 0.024 | 0.027 | 0.019 | 0.025 |

| (0.225) | (0.165) | (0.516) | (0.458) | (0.580) | (0.457) | |

| Tenure | 0.084 | 0.075 | 0.008 | 0.002 | −0.035 | −0.045 |

| (0.061) | (0.090) | (0.871) | (0.965) | (0.421) | (0.292) | |

| ESSL | 0.742 *** | 0.710 *** | 0.674 *** | 0.654 *** | 0.740 *** | 0.705 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| GSV | −0.073 * | 0.035 | 0.054 | 0.119 * | −0.024 | 0.094 * |

| (0.040) | (0.444) | (0.146) | (0.013) | (0.482) | (0.032) | |

| ESSL × GSV | 0.156 *** | 0.096 * | 0.173 *** | |||

| (0.000) | (0.032) | (0.000) | ||||

| R2 | 0.533 | 0.548 | 0.486 | 0.491 | 0.554 | 0.571 |

| Adj.R2 | 0.527 | 0.540 | 0.479 | 0.483 | 0.547 | 0.564 |

| F | 82.435 *** | 74.722 *** | 68.209 *** | 59.612 *** | 89.461 *** | 82.221 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yuan, B.; Li, J. Understanding the Impact of Environmentally Specific Servant Leadership on Employees’ Pro-Environmental Behaviors in the Workplace: Based on the Proactive Motivation Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 567. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010567

Yuan B, Li J. Understanding the Impact of Environmentally Specific Servant Leadership on Employees’ Pro-Environmental Behaviors in the Workplace: Based on the Proactive Motivation Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(1):567. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010567

Chicago/Turabian StyleYuan, Baolong, and Jingyu Li. 2023. "Understanding the Impact of Environmentally Specific Servant Leadership on Employees’ Pro-Environmental Behaviors in the Workplace: Based on the Proactive Motivation Model" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 1: 567. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010567

APA StyleYuan, B., & Li, J. (2023). Understanding the Impact of Environmentally Specific Servant Leadership on Employees’ Pro-Environmental Behaviors in the Workplace: Based on the Proactive Motivation Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 567. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010567