Do Resettled People Adapt to Their Current Geographical Environment? Evidence from Poverty-Stricken Areas of Northwest Yunnan Province, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

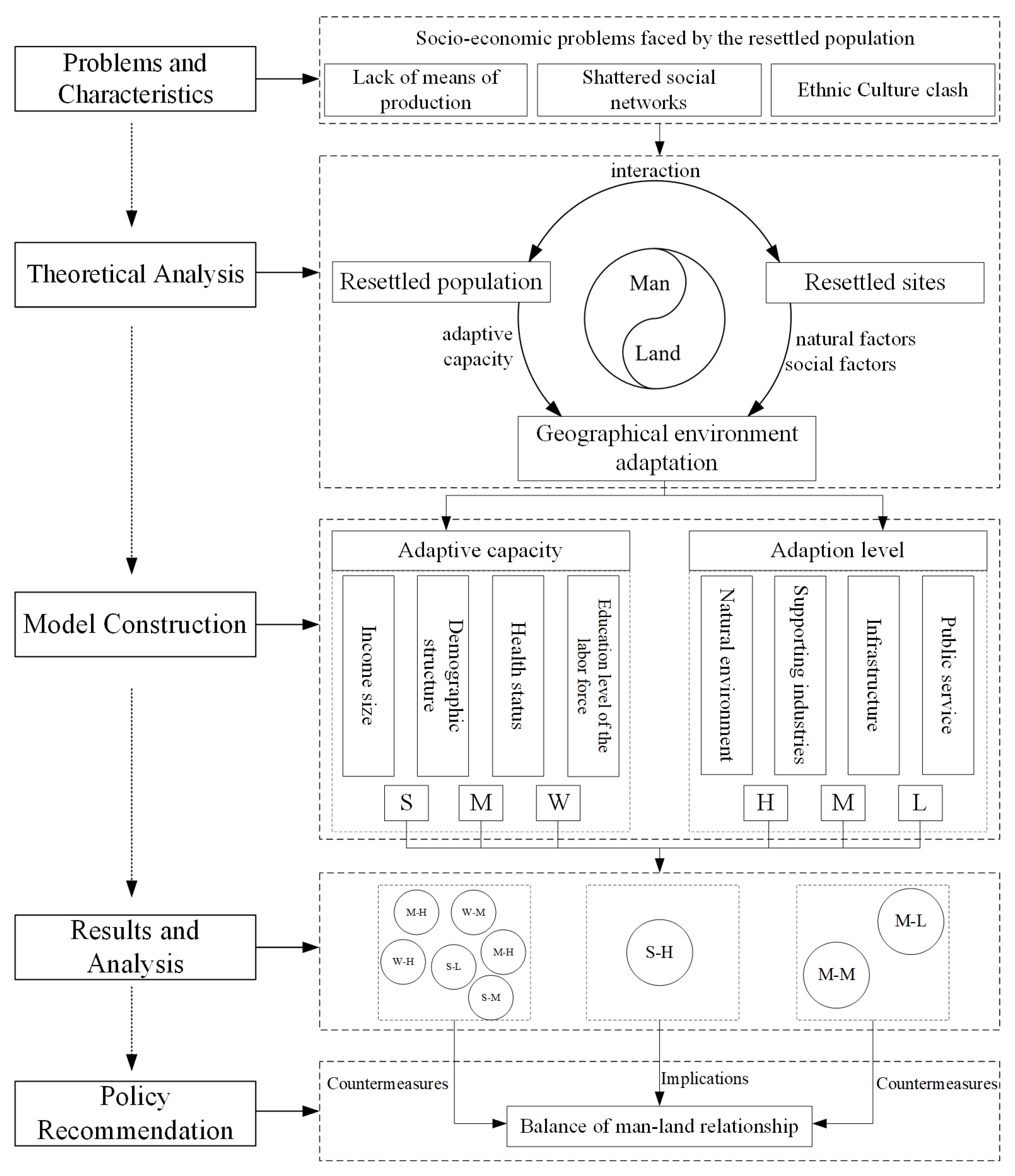

2. Literature Review and Conceptual Framework

2.1. The Theory of Man–Land Areal System

2.2. Geographical Environment Adaptive Capacity of Migrant Population

2.3. Follow-Up Development of Resettled Population

3. Materials and Methods

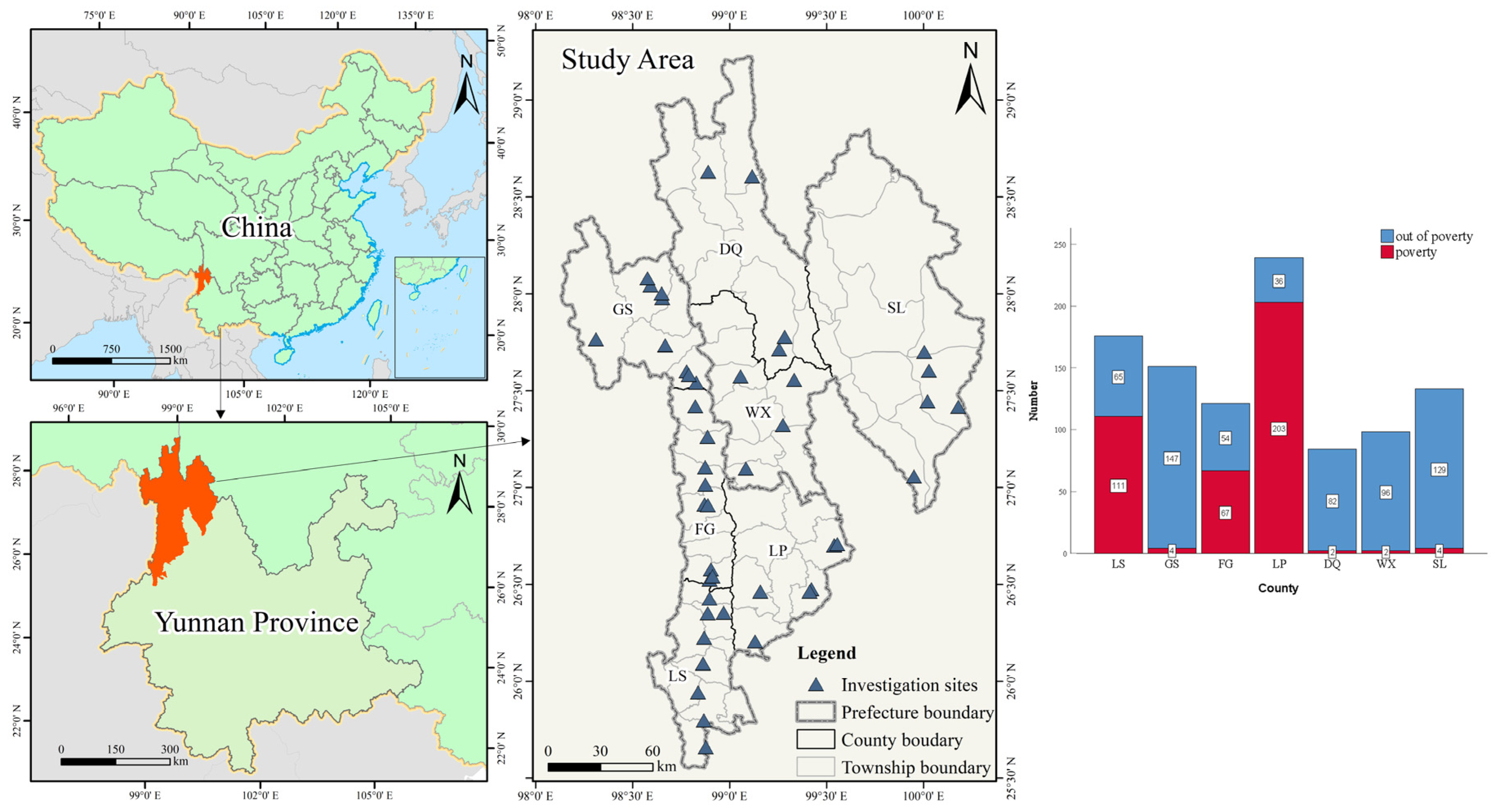

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Evaluation Indicator

3.3. Evaluation Method

3.3.1. Calculation Method of ACI

- (1)

- VEP

- (2)

- ACI

- (3)

- Family characteristic variables of resettled farmers

3.3.2. Calculation Method of ALI

- (1)

- Conceptual model of AL

- (2)

- Index system and index weight

- (3)

- Index normalization processing

- (4)

- The econometric model of ALI

3.4. Data Sources

- (1)

- Field Investigation

- (2)

- Nujiang and Diqing Prefectures Poverty Alleviation and Development Management System

- (3)

- Statistical Bulletin of National Economic and Social Development of Diqing Prefecture and Nujiang Prefecture in 2019.

4. Results and Analysis

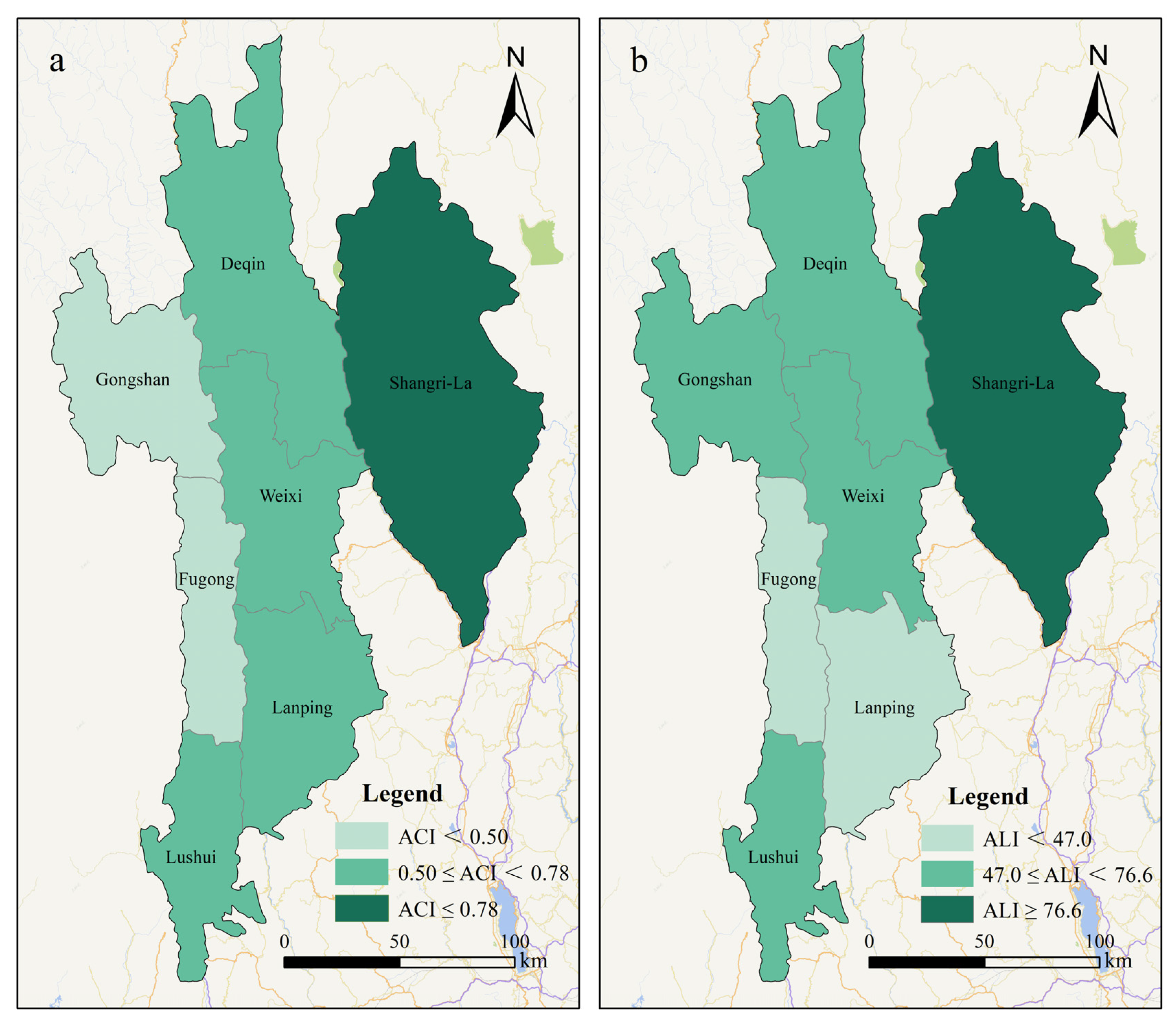

4.1. ACI

4.2. ALI

4.3. AC and Its Regional Differentiation Pattern

4.3.1. Overall AC of Resettled Population

4.3.2. Spatial Differentiation Pattern and Formation Mechanism of AC

4.4. AL and Its Regional Differentiation Pattern

4.4.1. Overall AL of Resettled Population

4.4.2. Spatial Differentiation Pattern and Formation Mechanism of AL

4.5. The Relationship between AC and AL

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, Y.; de Sherbinin, A.; Liu, Y. China’s poverty alleviation resettlement: Progress, problems and solutions. Habitat Int. 2020, 98, 102135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhao, Q.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yu, X. Poverty and Subjective Poverty in Rural China. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 150, 219–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fosu, A.K. Growth, inequality, and poverty reduction in developing countries: Recent global evidence. Res. Econ. 2017, 71, 306–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Liu, Y. Rural restructuring in China. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 387–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y. The nexus between regional eco-environmental degradation and rural impoverishment in China. Habitat Int. 2020, 96, 102086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Q.; Li, E.; Yang, Y. Politics, policies and rural poverty alleviation outcomes: Evidence from Lankao County, China. Habitat Int. 2022, 127, 102631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Liu, Y. Poverty alleviation through land assetization and its implications for rural revitalization in China. Land Use Policy 2021, 105, 105418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Zhang, F. The future path to China’s poverty reduction—Dynamic decomposition analysis with the evolution of China’s poverty reduction policies. Soc. Indic. Res. 2021, 158, 507–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Li, X.; Li, W.; Feng, J. Differences and Influencing Factors of Relative Poverty of Urban and Rural Residents in China Based on the Survey of 31 Provinces and Cities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Guo, Y.; Zhou, Y. Poverty alleviation in rural China: Policy changes, future challenges and policy implications. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2018, 10, 241–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, G.-X.; Feng, X.-L.; Qiu, H.-G. Income effects of poverty alleviation relocation program on rural farmers in China. J. Integr. Agric. 2021, 20, 891–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cernea, M.M. The Economics of Involuntary Resettlement: Questions and Challenges; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Y. Research progress in man-land relationship evolution and its resource-environment base in China. J. Geogr. Sci. 2017, 27, 899–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M.A.; Schoon, M.L.; Ke, W.; Börner, K. Scholarly networks on resilience, vulnerability and adaptation within the human dimensions of global environmental change. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2006, 16, 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, P.; Wang, J.; Chen, J. The future of human-environment interaction research in geography: Lessons from the 6th Open Meeting of IHDP. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2006, 61, 125. [Google Scholar]

- Dadao, L. Theoretical studies of man-land system as the core of geographical science. Geogr. Res. 2002, 21, 135–145. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, J. “Territorial system of human-environment interaction”: A theoretical cornerstone for comprehensive research on for-mation and evolution of the geographical pattern. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2018, 73, 597–607. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Ma, L.; Yao, Y.; Cui, X. Man-land relationship based on the spatial coupling of population and residential land–A case study of Yuzhong County in Longzhong Loess Hilly Region, China. Land Use Policy 2022, 116, 106059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Kong, X.; Li, Y. Identifying the Static and Dynamic Relationships Between Rural Population and Settlements in Jiangsu Province, China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2020, 30, 810–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitano, H. Systems Biology: A Brief Overview. Science 2002, 295, 1662–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steward, J.H. Theory of Culture Change: The Methodology of Multilinear Evolution; University of Illinois Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Tompkins, E.L.; Adger, W.N. Defining response capacity to enhance climate change policy. Environ. Sci. Policy 2005, 8, 562–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, E.; Marzall, K. Adaptive capacity for climate change in Canadian rural communities. Local Environ. 2006, 11, 373–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truelove, H.B.; Carrico, A.R.; Thabrew, L. A socio-psychological model for analyzing climate change adaptation: A case study of Sri Lankan paddy farmers. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2015, 31, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K.-A.; Liou, Y.-A.; Terry, J.P. Vulnerability of Vietnam to typhoons: A spatial assessment based on hazards, exposure and adaptive capacity. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 682, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adger, W.N. Social Aspects of Adaptive Capacity. Climate Change, Adaptive Capacity and Development; Imperial College Press: London, UK, 2003; pp. 29–49. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, S.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Li, F.; Huang, J. Review on adaptation in the perspective of global change. Prog. Geogr. 2011, 30, 1088–1098. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; Li, H. Social adaptation, political trust and satisfaction of relocation policy-Based on the survey of relocated farmers in the concentrated contiguous destitute areas in Hunan Province. Theory Pract. Financ. Econ. 2020, 41, 86–93. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, L. Research on the Interaction between Government and Farmers’ Professional Cooperatives in Poverty Governance—Taking H County in Guizhou Province as an Example. Bachelor’s Thesis, Guizhou University of Finance and Economics, Guiyang, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, F.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y. The Practice of the Reconstruction of Migration Multiple Space in Relocation Poverty Alleviation: Based on Dejiang County Cross-regional Migration Research. J. Huaihua Univ. 2019, 38, 67–71. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L.; Chen, Q. Management relationship and optimization of the poverty-alleviation management of the immigrant reset-tlement community. J. Yunnan Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2019, 18, 110–117. [Google Scholar]

- Lyv, C. Study on the Coordinated Development Path of Poverty Alleviation Relocation and Citizenization of Relocated Pop-ulation in Guangxi. Bachelor’s Thesis, Nanning Normal University, Nanning, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, B.; Huang, Z.; Teng, F. Continued Efforts Made after Relocation for Poverty Alleviation—Experience and Implications of the “New Citizen” Plan of Qianxinan Prefecture of Guizhou Province. Macroecon. Manag. 2021, 5, 84–90. [Google Scholar]

- Obokata, R.; Veronis, L.; McLeman, R. Empirical research on international environmental migration: A systematic review. Popul. Environ. 2014, 36, 111–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roland, H.B.; Curtis, K.J. The differential influence of geographic isolation on environmental migration: A study of internal migration amidst degrading conditions in the central Pacific. Popul. Environ. 2020, 42, 161–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehcheshmeh, M.M.; Ghaedi, S. Climate Change and Ecological Migration: A Study of Villages in the Province of Khuzestan, Iran. Environ. Res. Eng. Manag. 2020, 76, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorca-Rodríguez, C.M.; Casas-Jurado, A.C.; García-Fernández, R.M. Tourism and poverty alleviation: An empirical analysis using panel data on Peru’s departments. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 19, 746–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Ren, Q.; Yu, J. Impact of the ecological resettlement program on participating decision and poverty reduction in southern Shaanxi, China. For. Policy Econ. 2018, 95, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; Leng, G.; Feng, X.; Yang, S. Effects of the poverty alleviation relocation program on diet quality among low-income households. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2020, 13, 397–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Feng, X.; Wang, S. Study on Poverty Vulnerability of the Poor Relocated Households. Rural Econ. 2019, 3, 64–72. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, J.; Yin, H.; Wang, S.; Wang, Q. Does poverty alleviation relocation reduce poverty vulnerability: PSM-DID analysis based on the quasi-experimental study of the poverty alleviation relocation from 16 counties in 8 provinces. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2018, 28, 20–28. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, W.; Xie, Y.; Yan, S.; Zhou, X.; Li, C. The Reshaping of Neighboring Social Networks after Poverty Alleviation Relocation in Rural China: A Two-Year Observation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Rao, D.; Yang, L.; Min, Q. Subsidy, training or material supply? The impact path of eco-compensation method on farmers’ livelihood assets. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 287, 112339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-L.; Xu, M.; Zhou, K.-Y.; Zeng, F.-C.; Liu, Z.-M. Coupling development mechanism and typical ways of targeted poverty alleviation and eco-compensation in China: Case analysis based on forestry. J. Nat. Resour. 2019, 34, 989–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, B.; Yu, Y.; Ge, L.; Yang, L.; Guo, Y. Does Eco-Compensation Alleviate Rural Poverty? New Evidence from National Key Ecological Function Areas in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, J.H.; del Pilar Moreno-Sánchez, R. Estimating the adaptive capacity of local communities at marine protected areas in Latin America: A practical approach. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gillis, M.; Shoup, C.; Sicat, G.P. World Development Report 2000/2001-Attacking Poverty; The United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU-WIDER): Helsinki, Finland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Vo, T.T. Household vulnerability as expected poverty in Vietnam. World Dev. Perspect. 2018, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaiha, R.; Imai, K. Measuring Vulnerability and Poverty Estimates for Rural India; The United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU-WIDER): Helsinki, Finland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hoddinott, J.; Quisumbing, A. Methods for microeconometric risk and vulnerability assessment. In Risk, Shocks, and Human Development; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 62–100. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, Y.; Sha, Y.; Zhou, J.; Ren, H.; Shen, X.; Xu, H. The Effect of the “Triple-Layer Medical Security” Policy on the Vulnerability as Expected Poverty of Rural Households: Evidence from Yunnan Province, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Li, X.; Li, W. The Nexus between Credit Channels and Farm Household Vulnerability to Poverty: Evidence from Rural China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, S.; Jalan, J.; Suryahadi, A. Assessing Household Vulnerability to Poverty from Cross-Sectional Data: A Methodology and Estimates from Indonesia; Discussion paper no. 0102-52; Columbia University: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, S.S.; Wilk, M.B. An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrika 1965, 52, 591–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Gong, X.; Zhang, J.; Xiang, Z.; Liao, C. The Impact of Mobile Payment on Household Poverty Vulnerability: A Study Based on CHFS2017 in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paavola, J. Livelihoods, vulnerability and adaptation to climate change in Morogoro, Tanzania. Environ. Sci. Policy 2008, 11, 642–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, R.; Jha, S.K.; Alatalo, J.M.; Archie, K.M.; Gupta, A.K. Sustainable livelihood framework-based indicators for assessing climate change vulnerability and adaptation for Himalayan communities. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 79, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zeng, F. Poverty Reduction in China: Does the Agricultural Products Circulation Infrastructure Matter in Rural and Urban Areas? Agriculture 2022, 12, 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable Symbol | Variable | Description |

|---|---|---|

| sal | Proportion of salary income | Proportion of salary income in total household income |

| sca | Family scale | The total population of household registration |

| pla | Proportion of labor force | Labor force/total household population |

| non | Proportion of migrant workers population | Number of workers outside their county/total household population |

| chr | Serious or long-term chronic patients | Do they have serious or long-term chronic patients (the population with major diseases or long-term chronic diseases designated by rural medical insurance) at home? Yes = 1, No = 0 |

| def | Proportion of disabled people | Number of disabled people/total family population |

| ced | Proportion of population in compulsory education stage | Number of people attending compulsory education/total family population |

| hig | Proportion of population with high school and above | Number of people attending high school, junior college, university, postgraduate/total family population |

| tra | Income of land transfer | Income from land transfer in the form of leases, shares, etc. |

| wel | Public welfare positions | Have they enjoyed the public welfare positions (including forest rangers, river managers, border guards, road guards, cleaners and so on arranged by local governments)? Yes = 1, No = 0 |

| mla | Situation of enjoying the minimum living allowance (MLA) | Enjoy class A of MLA = 3, class B of MLA = 2, class C of MLA = 1, not = 0 |

| edu | Education level of householder | 0 for elementary school and below, 1 for middle school, 2 for high school and above |

| Dimensional Layer | Category Layer | Indexes Layer | Weight | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indexes | Explanation | |||

| Immigrant out of the bad environment 0.20 | Physical | Degree of relocation plan (X1) | Actual number of resettled households/planned number of resettled households | 0.254 |

| Proportion of resettled households breaking the contract (X2) | Number of households refusing to relocate in breach of contract/planned number relocation households | 0.170 | ||

| Psychology | Degree of relocation regret (X3) | Number of households that expressed regret after relocation/number of households resettled under field survey | 0.407 | |

| Proportion of households returning to farming (X4) | Number of households returning to farming after relocation/number of resettled households under field survey | 0.169 | ||

| Obtaining stability 0.45 | Life and culture | Adaptation of basic living (X5) | Number of households with clean household environment and correct use of household appliances and sanitary facilities/number of resettled households | 0.111 |

| Inheritance of ethnic culture (X6) | Good cultural heritage = 1, general = 0.5, poor = 0 (by interviewing community administrator) | 0.080 | ||

| Multi-ethnic cultural integration (X7) | Good participation in cultural activities = 1, general = 0.5, poor = 0 (by interviewing community administrator) | 0.096 | ||

| Social relations | Maintenance of original social relations (X8) | Number of households contacting relatives and friends “increased” and “unchanged” after relocation/number of surveyed resettled households | 0.079 | |

| Establishment of new social relations (X9) | Number of households that “communicate more and become more familiar with the resettled population that they did not know before” after relocation/number of households surveyed | 0.092 | ||

| Income | Annual per capital income (X10) | Per capita net income in 2018 (unit: CNY) | 0.136 | |

| Non-agricultural income share (X11) | Household non-agricultural income/total household income | 0.119 | ||

| Social security | Distance to the nearest primary school (X12) | Distance from placement to nearest primary school (unit: km) | 0.052 | |

| Distance to the nearest clinic (X13) | Distance from the resettlement site to the nearest clinic (unit: km) | 0.052 | ||

| Proportion of households enjoying public welfare posts (X14) | Number of households enjoying public welfare positions/number of households resettled under investigation | 0.074 | ||

| Proportion of households enjoying low insurance (X15) | Number of households enjoying low insurance/number of resettled households under investigation | 0.070 | ||

| Coverage rate of bottom protection (X16) | Number of households with a bottom protection/number of households that should enjoy the bottom line | 0.039 | ||

| Achieving prosperity 0.35 | Industry support | Per capita non-agricultural economic output value (X17) | Total output value of secondary and tertiary industries/total regional population in 2018 | 0.224 |

| Flexible employment | Proportion of local workers (X18) | Number of workers in their counties/number of labor force of resettled households under investigation | 0.176 | |

| Proportion of migrant workers (X19) | Number of migrant workers outside the county/number of labor force of resettled households under investigation | 0.200 | ||

| Asset income | Per capita eco- compensation income (X20) | Eco-compensation income/household population | 0.086 | |

| Per capita land transfer income (X21) | Land transfer income/ household population | 0.133 | ||

| Per capita village reclamation income (X22) | Village reclamation income/ household population | 0.067 | ||

| Per capita collective economic benefits (X23) | The collective economic benefits/household population | 0.114 | ||

| Regions | ACI | Regions | ACI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nujiang Prefecture | 0.592 | Diqing Prefecture | 0.765 |

| Gongshan County | 0.461 | Shangri-La City | 0.896 |

| Fugong County | 0.476 | Deqin County | 0.741 |

| Lushui City | 0.585 | Weixi County | 0.674 |

| Lanping County | 0.657 | Poverty-stricken areas of northwest Yunnan | 0.660 |

| Variables | ced | chr | def | edu | hig | lntra |

| Coefficient (its t-value) | 0.0023 (0.8784) | −0.0093 * (−8.7770) | −0.0497 * (11.2477) | 0.0043 * (7.5935) | 0.0243 * (6.2511) | 0.0079 * (39.9053) |

| Variables | mla | non | pla | sal | sca | wel |

| Coefficient (its t-value) | 0.0081 * (17.8760) | 0.1688 * (58.9680) | 0.0670 * (34.5145) | 0.0189 * (12.3062) | −0.0039 * (−30.5103) | 0.0284 * (30.6524) |

| Regions | ALI | Regions | ALI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nujiang Prefecture | 50.9 | Diqing Prefecture | 78.4 |

| Gongshan County | 53.1 | Shangri-La City | 86.5 |

| Fugong County | 43.4 | Deqin County | 76.0 |

| Lushui City | 65.2 | Weixi County | 63.8 |

| Lanping County | 44.7 | Poverty-stricken areas of northwest Yunnan | 61.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qu, L.; Xiao, W.; Gao, W. Do Resettled People Adapt to Their Current Geographical Environment? Evidence from Poverty-Stricken Areas of Northwest Yunnan Province, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 193. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010193

Qu L, Xiao W, Gao W. Do Resettled People Adapt to Their Current Geographical Environment? Evidence from Poverty-Stricken Areas of Northwest Yunnan Province, China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(1):193. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010193

Chicago/Turabian StyleQu, Liquan, Weidong Xiao, and Weidong Gao. 2023. "Do Resettled People Adapt to Their Current Geographical Environment? Evidence from Poverty-Stricken Areas of Northwest Yunnan Province, China" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 1: 193. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010193

APA StyleQu, L., Xiao, W., & Gao, W. (2023). Do Resettled People Adapt to Their Current Geographical Environment? Evidence from Poverty-Stricken Areas of Northwest Yunnan Province, China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 193. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010193