An Empirical Study on the Promotion of Students’ Physiological and Psychological Recovery in Green Space on Campuses in the Post-Epidemic Era

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- How do different types of green spaces on campus differ in terms of their physical and psychological restoration for college students?

- (2)

- What are the differences in the perception-restorative effects for college students of different types of green spaces on campus?

- (3)

- What is the relationship between the aesthetic preference of landscape elements and the perception-recovery of space under different kinds of landscape on the campus?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Study Sites

2.3. Experimental Design

2.4. Measurements

2.4.1. Physiological Measurements

2.4.2. Emotional State Measurement

2.4.3. Perceptual Recovery Measurements

2.4.4. Preference Questionnaire Measurements

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Restorative Differences in Different Landscape Types in Campus Environments

3.1.1. Physiological Results

3.1.2. Psychological Results

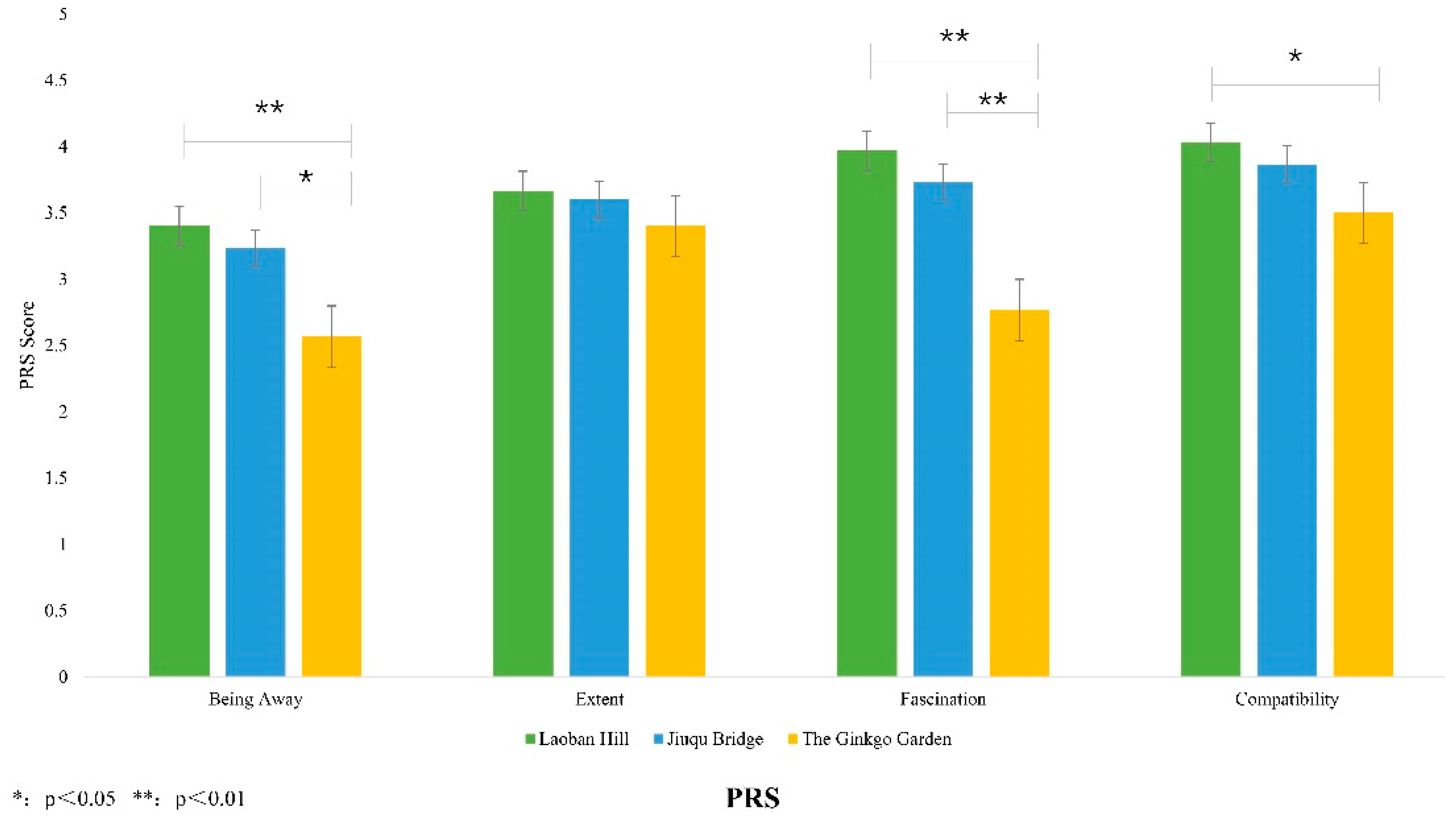

3.2. Differences in Aesthetic Preference and Restorative Perception of Landscape Elements in Campus Environments

4. Discussion

4.1. Different Effects of Landscape Types in the College Students’ Psychological Relaxation and Perception Recovery

4.2. Aesthetic Preference and Environmental Restoration Potential of Different Landscape Elements

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Landscape Elements | Landscape Components | Selecting Preferred Landscape Element Features | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flowers | Plant Height | Low Floor (10–20 cm) | |

| Middle layer (20–40 cm) | |||

| High Floor (40–60 cm) | |||

| Plant Color | simple color | ||

| colorful | |||

| Cool and Warm Colors | cool flower | ||

| Neutral flowers (white, black) | |||

| warm flowers | |||

| Flowering Season | Spring (February–April) | ||

| Summer (May–July) | |||

| Autumn (August–October) | |||

| Winter (November–January) | |||

| Arbor | Plant Density | Lush | |

| Medium | |||

| Sparse | |||

| Species | Evergreen tree | ||

| Deciduous tree | |||

| Ornamental Features | Flower viewing | ||

| Foliage | |||

| View dry | |||

| View branches | |||

| Plant Species | Less variety but uniform | ||

| variety | |||

| Plant Color | Simple color | ||

| Colorful | |||

| Plant Layer | Low-layer and simple | ||

| Multi-layer and rich | |||

| Gentle Slope | Trail Slope | 0–3° | |

| 3–10° | |||

| 10–27° | |||

| Shade Coverage | High (>50%) | ||

| Low (<50%) | |||

| Ladder | Step Width | Large (above 300 mm) | |

| General (240 mm–300 mm) | |||

| Step Aspect Ratio | Large (large step width, low height) | ||

| General | |||

| Shade Coverage | High (>50%) | ||

| Low (<50%) | |||

| Garden Pavilion | Harmony with the Environment | Highly integrated with the landscape environment, harmonious and unified | |

| Obvious differences in the landscape environment | |||

| View Probability | Open on all sides with great views | ||

| A certain occlusion, applying frame, scene leakage, and other techniques | |||

| Culture | Engraved with poem couplets, famous quotes, etc. | ||

| No poems, couplets, famous quotes, etc. | |||

| Landscape Stone | Size | Large Ornamental Stone (65–100 cm) | |

| Medium Ornamental Stone (20–65 cm) | |||

| Small Ornamental Stone (5–20 cm) | |||

| Harmony with the Environment | Highly integrated with the landscape environment (harmonious and unified) | ||

| Obvious differences in the overall landscape environment | |||

| Culture | Engraved with poem couplets, famous quotes, etc. | ||

| No poems, couplets, famous quotes, etc. | |||

| Cultural Card | Harmony with the Environment | Highly integrated with the landscape environment (harmonious and unified) | |

| Obvious differences in overall landscape environment | |||

| Culture | Engraved with poem couplets, famous quotes, etc. | ||

| No poems, couplets, famous quotes, etc. | |||

| Landscape Lamp Post | Street Light Height | High (above 4 m) | |

| General (3 m–4 m) | |||

| Short (2.5 m–3 m) | |||

| Lighting Effects | Bright (no dark areas at night) | ||

| Dark (partially dark areas at night, strong privacy) | |||

| Light Color | Cold | ||

| Warm | |||

| Types | Many (two or more types, including street lights, lawn lights, decorative lights, etc.) | ||

| Less (street lights only) | |||

| Garbage Can | Harmony with the Environment | Highly integrated with the landscape environment (harmonious and unified) | |

| Obvious differences in the overall landscape environment | |||

| Distribution | Even distribution (easy to use) | ||

| Centralized distribution to create a simple landscape environment | |||

| Rest Seat | High | Height (>48 cm) | |

| General (38 cm–48 cm) | |||

| Low (<38 cm) | |||

| Harmony with the Environment | Highly integrated with the landscape environment (harmonious and unified) | ||

| Obvious differences in the overall landscape environment | |||

| View Probability | Open viewing interface and highly observable landscape environment | ||

| Blocked viewing interface, and strong privacy | |||

| Distribution | Even distribution (easy to use) | ||

| Centralized distribution to create a simple landscape environment | |||

| Landscape Wall | Culture | Engraved with poem couplets, famous quotes, etc. | |

| No poems, couplets, famous quotes, etc. | |||

| Location | Straight Ahead | ||

| Side Of Sight | |||

| Sculpture | Size | Large Sculpture (above 3 m) | |

| Medium Sculpture (1.5–3 m) | |||

| Small sculpture (below 1.5 m) | |||

| Harmony with the Environment | Highly integrated with the landscape environment (harmonious and unified) | ||

| Obvious differences in the overall landscape environment | |||

| Behavioral Perception | Border Definition | Clear roads, boundaries, etc. | |

| Blurred roads, borders, etc. | |||

| Probability of Stay | Long-term Stay | ||

| Short Stay | |||

| No Stop | |||

| Sense of Security | Back interface, transparent line of sight, and a strong sense of security | ||

| Enclosed on three sides, blocked line of sight, and strong privacy | |||

| No enclosure, transparent line of sight, a strong sense of security | |||

| Walking Comfort (pavement material) | Asphalt Road | ||

| Concrete Pavement | |||

| Brick Pavement | |||

| Natural Stone Pavement | |||

| Wooden Pavement | |||

| Gravel Road | |||

| Twists and Turns of Space | Many changes in opening and closing space and strong emotional ups and downs | ||

| Less opening and closing space changes, more stable emotions | |||

| Landscape Elements | Landscape Components | Selecting Preferred Landscape Element Features | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aquatic Plants | Proportion of Water Surface | High (above 50%) | |

| Low (below 50%) | |||

| Flowering Season | Spring (February–April) | ||

| Summer (May–July) | |||

| Autumn (August–October) | |||

| Winter (November–January) | |||

| Plant Species | Less variety but uniform | ||

| Variety | |||

| Plant Color | Simple color | ||

| Colorful | |||

| Plant Layer | Low-layer and simple | ||

| Multi-layer and rich | |||

| Shrub | Boundary Enclosure | Creates a private space | |

| Creates open space | |||

| Plant Height | High (1.5–3 m) | ||

| Medium (0.5–1.5 m) | |||

| Low (below 0.5 m) | |||

| Plant Density | Lush | ||

| Medium | |||

| Sparse | |||

| Planting Method | Orphan | ||

| Group Planting | |||

| Planting | |||

| Plant Species | Less variety but uniform | ||

| Variety | |||

| Plant Color | Simple color | ||

| Colorful | |||

| Plant Layer | Low-layer and simple | ||

| Multi-layer and rich | |||

| Arbor | Plant Height | High (above 9 m) | |

| Medium (5–9 m) | |||

| Low (below 5 m) | |||

| Plant Density | Lush | ||

| Medium | |||

| Sparse | |||

| Planting Method | Orphan | ||

| Group Planting | |||

| Planting | |||

| Species | Evergreen Tree | ||

| Deciduous Tree | |||

| Ornamental Features | Flower viewing | ||

| Foliage | |||

| View dry | |||

| View branches | |||

| Plant Species | Less variety but uniform | ||

| Variety | |||

| Plant Color | Simple color | ||

| Colorful | |||

| Plant Layer | Low-layer and simple | ||

| Multi-layer and rich | |||

| Climbing Plants | D/H of Road Width and Climbing Height | <1:1—(high borders, narrow roads) | |

| ≈1:1 (the height of the border is comparable to the width of the road) | |||

| >1:1 (low border, wide road) | |||

| Flowering Season | Spring (February–April) | ||

| Summer (May–July) | |||

| Autumn (August–October) | |||

| Winter (November–January) | |||

| Plant Species | Less variety but uniform | ||

| Variety | |||

| Plant Color | Simple color | ||

| Colorful | |||

| Plant Layer | Low-layer and simple | ||

| Multi-layer and rich | |||

| Lake | Number of Aquatic (higher) animals | Many (more than 6) | |

| less (1–5) | |||

| Aquatic (lower) Animal Characteristics | Have | ||

| None | |||

| Water State | Dynamic Water Feature | ||

| Static Water Feature | |||

| Terrain | Flatness | Flat Terrain | |

| Full Of Ups and Downs | |||

| Shade Coverage | High (>50%) | ||

| Low (<50%) | |||

| Garden Pavilion | Harmony with the Environment | Highly integrated with the landscape environment (harmonious and unified) | |

| Obvious differences in the landscape environment | |||

| View Probability | Open on all sides with great views | ||

| a certain occlusion, applying frame, scene leakage, and other techniques | |||

| Culture | Engraved with poem couplets, famous quotes, etc. | ||

| No poems, couplets, famous quotes, etc. | |||

| Garden Bridge | Scale | Width (>2.2 m) | |

| Suitable (1.1 m–2.2 m) | |||

| Narrow (<1.1 m) | |||

| Guardrail Height | High guardrail height, good safety | ||

| Guardrail height is suitable | |||

| Low guardrail height or no guardrail, high closeness to the environment | |||

| Harmony with the Environment | Highly integrated with the landscape environment, harmonious and unified | ||

| There are obvious differences in the overall landscape environment | |||

| Sense of Space | Open space, easy to see | ||

| constricted space, and concentrated line of sight | |||

| Route Settings | Straight and easy to navigate | ||

| Twisted for easy viewing | |||

| Culture | Engraved with poem couplets, famous quotes, etc. | ||

| No poems, couplets, famous quotes, etc. | |||

| Proximity with Plants | Tall (easy-to-touch plants) | ||

| General (can-touch plants) | |||

| Low (a certain distance from plants) | |||

| Proximity with Water | High (easy-to-touch the water) | ||

| General (can-touch the water) | |||

| Low, a certain distance from the water | |||

| Landscape Stone | Size | Large Ornamental Stone (65–100 cm) | |

| Medium Ornamental Stone (20–65 cm) | |||

| Small Ornamental Stone (5–20 cm) | |||

| Harmony with the Environment | Highly integrated with the landscape environment (harmonious and unified) | ||

| Obvious differences in overall landscape environment | |||

| Culture | Engraved with poem couplets, famous quotes, etc. | ||

| No poems, couplets, famous quotes, etc. | |||

| Landscape Lamp Post | Street Light Height | High (above 4 m) | |

| General (3 m–4 m) | |||

| Short (2.5 m–3 m) | |||

| Lighting Effects | Bright (no dark areas at night) | ||

| Dark (partially dark areas at night, strong privacy) | |||

| Light Color | Cold | ||

| Warm | |||

| Types | Many (two or more types, including street lights, lawn lights, decorative lights, etc.) | ||

| Less (street lights only) | |||

| Garbage Can | Harmony with the Environment | Highly integrated with the landscape environment (harmonious and unified) | |

| Obvious differences in the overall landscape environment | |||

| Distribution | Even distribution, easy to use | ||

| Centralized distribution to create a simple landscape environment | |||

| Rest Seat | High | Height (>48 cm) | |

| General (38 cm–48 cm) | |||

| Low (<38 cm) | |||

| Harmony with the Environment | Highly integrated with the landscape environment (harmonious and unified) | ||

| Obvious differences in the overall landscape environment | |||

| View Probability | open viewing interface, and highly observable landscape environment | ||

| blocked viewing interface, and strong privacy | |||

| Behavioral Perception | Border Definition | Clear roads, boundaries, etc. | |

| Blurred roads, borders, etc. | |||

| Probability of Stay | Long-term Stay | ||

| Short Stay | |||

| No Stop | |||

| Sense of Security | Back interface, transparent line of sight, and a strong sense of security | ||

| Enclosed on three sides, blocked line of sight, and strong privacy | |||

| No enclosure, transparent line of sight, a strong sense of security | |||

| Walking Comfort (pavement material) Border Definition | Asphalt Road | ||

| Concrete Pavement | |||

| Brick Pavement | |||

| Natural Stone Pavement | |||

| Clear roads, boundaries, etc. | |||

| Blurred roads, borders, etc. | |||

| Probability of Stay | Long-term Stay | ||

| Short Stay | |||

| Landscape Elements | Landscape Components | Selecting Preferred Landscape Element Features | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lawn | Lawn Fineness | Rough (leaf width > 3 mm) | |

| Delicate (leaf width 1.5–3 mm) | |||

| Height of Cut | Height (>8 cm) | ||

| Medium (4–8 cm) | |||

| Low (<4 cm) | |||

| Turf Purity Proportion | Pure Lawn | ||

| 30% Of Other Grass and Flowers | |||

| 60% Of Other Grass and Flowers | |||

| Flowers | Plant Height | Low Floor (10–20 cm) | |

| The middle layer (20–40 cm) | |||

| High Floor (40–60 cm) | |||

| Plant Color | Simple Color | ||

| Colorful | |||

| Cool and Warm Colors | Cool Flower | ||

| Neutral Flowers (white, black) | |||

| Warm Flowers | |||

| Flowering Season | Spring (February–April) | ||

| Summer (May–July) | |||

| Autumn (August–October) | |||

| Winter (November–January) | |||

| Arbor | Branch Point Height | High (above 4 m) | |

| Low (2.5 m–4 m) | |||

| Branch Uniformity | Tidy | ||

| Scattered | |||

| Plant Height | Height (9 m) | ||

| Medium (5–9 m) | |||

| Low (below 5 m) | |||

| Planting Density | Lush | ||

| Medium | |||

| Sparse | |||

| Species | Evergreen tree | ||

| Deciduous tree | |||

| Ornamental Features | Flower viewing | ||

| Foliage | |||

| View dry | |||

| View branches | |||

| Plant Species | Less variety but uniform | ||

| Variety | |||

| Plant Color | Simple color | ||

| Colorful | |||

| Plant Layer | Low layer and simple | ||

| Multi-layer and rich | |||

| Terrain | Flatness | Flat Terrain | |

| Full of Ups and Downs | |||

| Shade Coverage | High (>50%) | ||

| Low (<50%) | |||

| Landscape Stone | Size | Large Ornamental Stone (65–100 cm) | |

| Medium Ornamental Stone (20–65 cm) | |||

| Small Ornamental Stone (5–20 cm) | |||

| Harmony with the Environment | Highly integrated with the landscape environment (harmonious and unified) | ||

| Obvious differences in overall landscape environment | |||

| Culture | Engraved with poem couplets, famous quotes, etc. | ||

| No poems, couplets, famous quotes, etc. | |||

| Rest Seat | High | Height (>48 cm) | |

| General (38 cm–48 cm) | |||

| Low (<38 cm) | |||

| Harmony with the Environment | Highly integrated with the landscape environment (harmonious and unified) | ||

| Obvious differences in the overall landscape environment | |||

| View Probability | Open viewing interface, and highly observable landscape environment | ||

| Blocked viewing interface and strong privacy | |||

| Distribution | Even distribution (easy to use) | ||

| Centralized distribution to create a simple landscape environment | |||

| Landscape Lamp Post | Street Light Height | High (above 4 m) | |

| General (3 m–4 m) | |||

| Short (2.5 m–3 m) | |||

| Lighting Effects | Bright (no dark areas at night) | ||

| Dark (partially dark areas at night, strong privacy) | |||

| Light Color | Cold | ||

| Warm | |||

| Types | Many (two or more types, including street lights, lawn lights, decorative lights, etc.) | ||

| Less (street lights only) | |||

| Behavioral Perception | Border Definition | Clear roads, boundaries, etc. | |

| Blurred roads, borders, etc. | |||

| Probability of Stay | Long-term Stay | ||

| Short Stay | |||

| No Stop | |||

| Sense of Security | Back interface, transparent line of sight, and strong sense of security | ||

| Enclosed on three sides, blocked line of sight, and strong privacy | |||

| No enclosure, transparent line of sight, a strong sense of security | |||

| Walking Comfort (pavement material) | Asphalt Road | ||

| Concrete Pavement | |||

| Brick Pavement | |||

| Natural Stone Pavement | |||

| Wooden Pavement | |||

| Gravel Road | |||

| Twists and Turns of Space | Many changes in opening and closing space, and strong emotional ups and downs | ||

| Less space opening and closing changes, more stable emotions | |||

References

- Available online: https://unhabitat.org/wcr/ (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Velarde, M.; Fry, G. Health Effects of Viewing Landscape-Landscape Types in Environmental Psychology. Urban For. Urban Green. 2007, 6, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q. College Students’ Pressure and Subjective Well-Being: The Intermediary Role Played by Psychological Capital and the Regulatory Role Played by Social Support; Sichuan Normal University: Chengdu, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, J.H. Mental health status and its influencing factors among college students during the epidemic of COVID-19. South Med. Univ. 2020, 40, 171–176. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, E.O. The Nature of Human Nature. In Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life; Kellert, S.R., Heerwagen, J., Mador, M.L., Eds.; John Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Korpela, K.; Haritig, T. Restorative of qualities of favorite places. J. Environ. Psychol. 1996, 16, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T.; Kaiser, F.G.; Bowler, P.A. Further Development of a Measure of Perceived Environmental Restorativeness; Uppsala University, Institute of Housing Research: Gävle, Sweden, 1997; p. 232. [Google Scholar]

- Bowler, D.E.; Buyung-Ali, L.M.; Knight, T.M.; Pullin, A.S. A systematic review of evidence for the added benefits to health of exposure to natural environments. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stigsdotter, U.K.; Corazon, S.S.; Sidenius, U.; Kristiansen, J.; Grahn, P.A. It is not all bad for the grey city—A crossover study on physiological and psychological restoration in a forest and an urban environment. Health Place 2017, 46, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; He, Y.; Yu, Y. Enhanced functional connectivity properties of human brains during in-situ nature experience. PeerJ 2016, 4, e2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpela, K.M.; Ylén, M. Favorite green, waterside and urban environments, restorative experiences and perceived health in Finland. Health Promot. Int. 2010, 25, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, I.-C.; Tsai, Y.-P.; Lin, Y.-J.; Chen, J.-H.; Hsieh, C.-H.; Hung, S.-H.; Chang, C.-Y. Using functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) to analyze brain region activity when viewing landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 162, 137–144. [Google Scholar]

- Scholl, K.G.; Gulwadi, G.B. Recognizing campus spaces as learning spaces. J. Learn. Spaces 2015, 4, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Hipp, J.A.; Gulwadi, G.B.; Alves, S. The relationship between perceived greenness and perceived restorativeness of university campuses and student-reported quality of life. Environ. Behav. 2016, 48, 1292–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C. Study on Behavior of Visiting Campus Green Space’ Role in Emotion Regulation under the Influence of Multi-factors: Take 3 Universities in Beijing for Example. Landsc. Archit. 2018, 3, 46–52. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, L. Research on Campus Landscape Design Aiming to Mental Stress Restoration—Taking China University of Mining and Technology Nanhu Campus as Example; China University of Mining and Technology: Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, H.; Tao, J.; Guo, L.; Jiang, M.; Aii, L.; Zhihui, J.; Zongfang, L.; Qibing, C. Effects of Walking in Bamboo Forest and City Environments on Brainwave Activity in Young Adults. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2018, 2018, 9653857. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Zhao, J.; Meitner, M.J.; Hu, Y.; Xu, X. Characteristics of urban green spaces in relation to aesthetic preference and stress recovery. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 41, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Luo, H.; Ma, J.; Huang, Z.; Sun, L.-X.; Jiang, M.-Y.; Zhu, C.-Y.; Li, X. Effects of integration between visual stimuli and auditory stimuli on restorative potential and aesthetic preference in urban green spaces. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 53, 126702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, N.; Adger, W.N.; Agnolucci, P. Health and climate change: Policy responses to protect public health. Lancet Comm. 2015, 386, 1861–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.-X.; Rodiek, S.; Wu, C.-Z.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y.-X. Stress recovery and restorative effects of viewing different urban park scenes in Shanghai, China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2016, 15, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grahn, P.; Stigsdotter, U.K. The relation between perceived sensory dimensions of urban green space and stress restoration. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 94, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Zhu, S.; Mac Naughton, P.; Allen, J.G.; Spengler, J.D. Physiological and cognitive performance of exposure to biophilic indoor environment. Build. Environ. 2018, 132, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.L. Bried introduction of POMS scale and its model for China. J. Tianjin Inst. Phys. Education. 1995, 10, 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- Hartig, T.; Korpela, K.; Evans, G.W. A Measure of Restorative Quality in Environments. Scand. Hous. Plan. Res. 1997, 14, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.Z.; Huang, F.M.; Zhou, X.J. The relationships between environment preferences and restorative perceptions of environment: A case of mountainscape. Outdoor Recreat. Study 2008, 21, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y.J. The Impact of the Restorative Environment in University Campus on Student Health—A Case Study of Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University; Jinshan Campus, Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University: Fuzhou, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, R.S.; Simons, R.F.; Losito, B.D.; Fiorito, E.; Miles, M.A.; Zelson, M. Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environment. J. Environ. Psychol. 1991, 11, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T.; Mang, M.; Evans, G.W. Restorative effects of natural environment experience. Environ. Behav. 1991, 23, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.X. Study on the Effects of Different Landscapes on Elderly People’s Body Mind Health. Landsc. Archit. 2016, 7, 113–120. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, N.; Li, S.H.; Li, F.H. Study on the Effect of Different Landscapes on Human Psychology. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2008, 7, 69–72. [Google Scholar]

- Sonntag-Öström. “Nature’s effect on my mind”—Patients’ qualitative experiences of a forest-based rehabilitation programme. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Dong, N.N.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Ding, X. Study on the health impacts of urban park use in Shanghai. Landsc. Archit. 2017, 9, 99–105. [Google Scholar]

- Tina, G.; Mathias, H. Perception and Preference of Trees: A Psychological Contribution to Tree Species Selection in Urban Areas. Urban For. Urban Green. 2016, 15, 103–111. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle, H.; Hitchmough, J.; Jorgensen, A. All about the ‘wow factor’? The relationships between aesthetics, restorative effect and perceived biodiversity in designed urban planting. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 164, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.H.; Liu, C.; Yao, Y.N. Therapeutic Landscape Research Fronts: Hot Issues and Research Methods. South Archit. 2018, 3, 4–10. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, H.C.; Zhu, X. Study on the Effect of Spatial Characteristics and Health Restoration of Urban Parks in Harbin City in Autumn—Taking Zhaolin Park as an Example. J. Hum. Settl. West China 2018, 4, 73–79. [Google Scholar]

- Appleton, J. The Experience of Landscape; Hull University Press: Hull, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, R.S. Effects of gardens on health outcomes. Theory and research. In Healing Gardens: Therapeutic Benefits and Design Recommendations; Cooper Marcus, C., Barnes, M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 27–86. [Google Scholar]

- Währborg, P. Stress och den nya ohälsan (Stress and the New Ill-Health); Natur och Kultur: Stockholm, Sweden, 2002. (In Swedish) [Google Scholar]

- Choudhry, K.Z.; Coles, R.; Qureshi, S.; Ashford, R.; Khan, S.; Mir, R.R. A review of methodologies used in studies investigating human behavior as determinant of outcome for exposure to ‘naturalistic and urban environment’. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 527–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pals, R.; Steg, L.; Siero, F.W.; van der Zee, K.I. Development of the PRCQ: A measure of perceived restorative characteristics of ZOO attractions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, T.R.; Maguire, C.P.; Nebel, M.B. Assessing the restorative components of environments. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berga, A.E.; Kooleb, S.L.; van der Wulpb, N.Y. Environmental preference and restoration: (How) are they related? J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.T.; Liu, Z.F.; Chen, Q.B. A Study on Plant Landscape Preference and Restorative Perception of Linpan in West Sichuan. In Advances in Ornamental Horticulture Research in China; China Forestry Press: Beijing, China, 2018; pp. 643–649. [Google Scholar]

- Arriaza, M.; Cañas-Ortega, J.F.; Cañas-Madueño, J.A.; Ruiz-Aviles, P. Assessing the visual quality of rural landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2004, 69, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, J.; Bond, N. Museums as Restorative Environments. Curator Mus. J. 2010, 53, 421–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Pan, G.H.; Gao, Q. The Gestalt of Experience: Gestalt Psychology; Shandong Education Press: Jinan, China, 2009; Volume 102, pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.N. A Research on Texture of Landscape Space Impacts on People’s Psychological Emotions; Qi Lu University of Technology: Jinan, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, Z.J.; Kang, Y.X.; Li, M.D. Physiological and Psychological Influences of the Landscape Plant Forms on Human. J. Northwest For. Univ. 2015, 2, 283–286. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H. The Effects of Garden Plant Colors on Human Physiology and Psychology. Art Educ. Res. 2017, 7, 100–101. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, S. The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L. The Effects of Different Types of Natural Water Landscape on Physical and Mental Health of College Students; Sichuan Agricultural University: Chengdu, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, H.Y. Effect Mechanism and Spatial Optimization of Community Park Restoration Environment—A Case Study of Chongqing; Chongqing University: Chongqing, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gatersleben, B.S.; Andrews, M. When walking in nature is not restorative—The role of prospect and refuge. Health Place 2013, 20, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, J.J. Based on the Health Perspective, the Research of Restorative Environment in University Campus and Spatial Optimization; Shenzhen University: Shenzhen, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.Y. Research on the Influence of Types and Features of Blue-Green Space on Pressure Recovery; Harbin Institute of Technology: Harbin, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tabrizian, P.; Baran, P.K.; Smith, W.R.; Meentemeyer, R.K. Exploring perceived restoration potential of urban green enclosure through immersive virtual environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 2018, 55, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow. Psychological Assessment; Renmin University Press: Beijing, China, 1943; pp. 370–396. [Google Scholar]

- Puranen, B. Tuberculosis. Its Occurrence and Causes in Sweden 1750–1980. Doctoral Thesis, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden, 1984. [Google Scholar]

| Site | Laoban Hill | Jiuqu Bridge | The Ginkgo Garden |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mapping |  |  |  |

| Site Area | S = 158,250 m2 | S = 5676 m2 | S = 4746 m2 |

| Images |  |  |  |

|  |  | |

|  |  | |

|  |  | |

| Spatial Types | A natural and serene space. | A cultural refuge space. | A foreground social space. |

| Laoban Hill | Standardized Coefficient | T | Salience | 95.0% Confidence Interval for Beta | Collinear Statistics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | Upper Limit | Lower Limit | Tolerance | VIF | ||||

| Being Away (R2 = 48.8%) | View probability of Rest Seat | 0.443 | 3.158 | 0.004 | 0.382 | 1.805 | 0.999 | 1.001 |

| Gentle slope of the trail | −0.353 | −2.501 | 0.019 | −1.066 | −0.104 | 0.985 | 1.015 | |

| Ladder shade coverage | 0.354 | 2.501 | 0.019 | 0.135 | 1.387 | 0.984 | 1.016 | |

| Extent (R2 = 45.2%) | Arbor species | −0.444 | −2.903 | 0.007 | −2.640 | −0.451 | 0.907 | 1.103 |

| Cultural character of the landscape wall | 0.353 | 2.155 | 0.041 | 0.029 | 1.243 | 0.789 | 1.267 | |

| Fascination (R2 = 21.0%) | Harmony of sculpture with the environment | 0.458 | 2.726 | 0.011 | 0.211 | 1.489 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Compatibility (R2 = 37.1%) | Flowering season | −0.381 | −2.366 | 0.025 | −0.516 | −0.037 | 0.900 | 1.111 |

| Cultural character of the landscape wall | 0.370 | 2.299 | 0.029 | 0.066 | 1.155 | 0.900 | 1.111 | |

| Jiuqu Bridge | Standardized Coefficient | T | Salience | 95.0% Confidence Interval for Beta | Collinear Statistics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | Upper Limit | Lower Limit | Tolerance | VIF | ||||

| Being Away (R2 = 48.8%) | Proximity between garden bridge and plants | −0.381 | −2.183 | 0.038 | 0.041 | 1.277 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Extent (R2 = 45.2%) | Proximity between garden bridge and water | −0.386 | −2.216 | 0.035 | −0.748 | −0.029 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Fascination (R2 = 21.0%) | State of the Lake Water | 0.463 | 3.429 | 0.002 | 0.407 | 1.625 | 0.996 | 1.004 |

| Climbing plant species | −0.581 | −3.745 | 0.001 | −1.675 | −0.488 | 0.753 | 1.327 | |

| Layer of aquatic plants | −0.449 | −2.896 | 0.008 | −1.612 | −0.273 | 0.754 | 1.326 | |

| Compatibility (R2 = 37.1%) | Landscape lamp post light color | −0.368 | −2.490 | 0.019 | −1.401 | −0.134 | 0.974 | 1.027 |

| Landscape lamp post height | 0.404 | 2.766 | 0.010 | 0.178 | 1.206 | 0.997 | 1.003 | |

| Harmony of garden pavilion and environment | 0.357 | 2.413 | 0.023 | 0.195 | 2.443 | 0.972 | 1.029 | |

| The Ginkgo Garden | Standardized Coefficient | T | Salience | 95.0% Confidence Interval for Beta | Collinear Statistics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | Upper Limit | Lower Limit | Tolerance | VIF | ||||

| Being Away (R2 = 32.6%) | Arbor planting density | −0.424 | −2.685 | 0.012 | −1.103 | −0.147 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Distribution of rest seats | −0.382 | −2.420 | 0.023 | −2.995 | −0.247 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |

| Extent (R2 = 17.9%) | Distribution of rest seats | −0.424 | −2.475 | 0.020 | −4.538 | −0.428 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Fascination (R2 = 46.6%) | Clarity of boundary | 0.582 | 4.057 | 0.000 | 0.865 | 2.635 | 0.962 | 1.040 |

| Harmony of landscape stone with the environment | 0.489 | 3.409 | 0.002 | 0.498 | 2.002 | 0.962 | 1.040 | |

| Compatibility (R2 = 41.0%) | Clarity of boundary | 0.493 | 3.315 | 0.003 | 0.509 | 2.164 | 0.988 | 1.012 |

| Probability of staying at the site | 0.359 | 2.416 | 0.023 | 0.104 | 1.271 | 0.988 | 1.012 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, P.; He, Q.; Chen, Z.; Li, X.; Ma, J. An Empirical Study on the Promotion of Students’ Physiological and Psychological Recovery in Green Space on Campuses in the Post-Epidemic Era. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 151. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010151

Zhang P, He Q, Chen Z, Li X, Ma J. An Empirical Study on the Promotion of Students’ Physiological and Psychological Recovery in Green Space on Campuses in the Post-Epidemic Era. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(1):151. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010151

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Ping, Qianyi He, Zexuan Chen, Xi Li, and Jun Ma. 2023. "An Empirical Study on the Promotion of Students’ Physiological and Psychological Recovery in Green Space on Campuses in the Post-Epidemic Era" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 1: 151. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010151

APA StyleZhang, P., He, Q., Chen, Z., Li, X., & Ma, J. (2023). An Empirical Study on the Promotion of Students’ Physiological and Psychological Recovery in Green Space on Campuses in the Post-Epidemic Era. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 151. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010151