Validation of the Organizational Dehumanization Scale in Spanish-Speaking Contexts

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Measures for Criterion Validity

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Data Analysis Strategy

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Enunciados | Total Desacuerdo | Grado | Acuerdo total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | (Removed) Mi organización me hace sentir que un trabajador es tan bueno como cualquier otro. | Total desacuerdo | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | Acuerdo total |

| 2. | Mi organización no dudaría en reemplazarme si eso permitiera a la compañía obtener mayores beneficios. | Total desacuerdo | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | Acuerdo total |

| 3. | Si mi trabajo pudiera ser realizado por una máquina o un robot, mi organización no dudaría en reemplazarme por esta nueva tecnología. | Total desacuerdo | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | Acuerdo total |

| 4. | Mi organización me considera como una herramienta a usar para sus propios fines. | Total desacuerdo | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | Acuerdo total |

| 5. | Mi organización me considera como una herramienta para su propio éxito. | Total desacuerdo | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | Acuerdo total |

| 6. | Mi organización me hace sentir que lo único importante es mi desempeño laboral. | Total desacuerdo | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | Acuerdo total |

| 7. | Mi organización sólo está interesada en mí cuando me necesita. | Total desacuerdo | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | Acuerdo total |

| 8. | Lo único que cuenta en mi organización es lo que yo pueda contribuir a esta. | Total desacuerdo | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | Acuerdo total |

| 9. | Mi organización me trata como si fuera un robot. | Total desacuerdo | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | Acuerdo total |

| 10. | Mi organización me considera como un número. | Total desacuerdo | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | Acuerdo total |

| 11. | Mi organización me trata como si fuera un objeto. | Total desacuerdo | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | Acuerdo total |

References

- Bell, C.M.; Khoury, C. Organizational De/Humanization, Deindividuation, Anomie, and In/Justice. In Emerging Perspectives on Organizational Justice and Ethics; Gilliland, S., Steiner, D., Skarlicki, D., Eds.; IAP Information Age Publishing: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2011; pp. 167–197. [Google Scholar]

- Rochford, K.C.; Jack, A.I.; Boyatzis, R.E.; French, S.E. Ethical Leadership as a Balance Between Opposing Neural Networks. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 144, 755–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, K.; Mulligan, M. Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844; Prometheus: Buffalo, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim, E.; Buss, R. On Suicide; Penguin: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, M.; Parsons, T. The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism; Scribner: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Leyens, J.; Paladino, P.; Rodríguez-Torres, R.; Vaes, J.; Demoulin, S.; Rodríguez, A.; Gaunt, R. The Emotional Side of Prejudice: The Attribution of Secondary Emotions to Ingroups and Outgroups. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2000, 4, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyens, J.P.; Rodríguez-Torres, R.; Rodríguez-Perez, A.; Gaunt, R.; Paladino, M.; Vaes, J.; Demoulin, S. Psychological Essentialism and The Differential Attribution of Uniquely Human Emotions to Ingroups and Outgroups. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 31, 395–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, N. Dehumanization: An Integrative Review. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 10, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haslam, N.; Loughnan, S. Dehumanization and infrahumanization. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2014, 65, 399–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, N. Dependencia Contextual de La Infrahumanizacion. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Demoulin, S.; Rodriguez-Torres, R.; Rodríguez-Pérez, A.; Vaes, J.; Paladino, P.; Gaunt, R.; Cortés, B.; Leyens, J.P. Emotional Prejudice Can Lead to Infrahumanization. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 15, 259–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyens, J.; Cortés, B.; Demoulin, S.; Dovidio, J.; Fiske, S.T.; Gaunt, R.; Paladino, P.; Rodríguez-Pérez, A.; Rodríguez-Torres, R.; Vaes, J. Emotional Prejudice, Essentialism, and Nationalism. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 33, 703–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, N.; Kashima, Y.; Loughnan, S.; Shi, J.; Suitner, C. Subhuman, Inhuman, and Superhuman: Contrasting Humans with Nonhumans in Three Cultures. Soc. Cogn. 2008, 26, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christoff, K. Dehumanization in Organizational Settings: Some Scientific and Ethical Considerations. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Loughnan, S.; Haslam, N. Animals and Androids: Implicit Associations between Social Categories and Nonhumans. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 18, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, O.; Waytz, A. Dehumanization in Medicine: Causes, Solutions, and Functions. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 7, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martínez, R. Animalizar y Mecanizar: Dos Formas de Deshumanización. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Granada, Granada, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Väyrynen, T.; Laari-Salmela, S. Men, Mammals, or Machines? Dehumanization Embedded in Organizational Practices. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 147, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederickson, B.; Roberts, T. Objectification Theory: Toward Understanding Women’s Lived Experiences and Mental Health Risks. Psychol. Women Q. 1997, 21, 173–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussbaum, M. Objectification. Philos. Public Aff. 1995, 24, 249–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galinski, A.; Magee, J.; Inesi, M.E.; Gruenfeld, D. Power and Perspectives Not Taken. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 17, 1068–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruenfeld, D.; Inesi, E.; Magee, J.; Galinsky, A. Power and the Objectification of Social Targets. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 95, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haslam, N.; Bain, P. Humanizing the Self: Moderators of the Attribution of Lesser Humanness to Others. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2007, 33, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lammers, J.; Galinsky, A.D.; Gordijnn, E.H.; Otten, S. Power Increases Social Distance. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2012, 3, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudman, L.; Mescher, K. Of Animals and Objects: Men’s Implicit Dehumanization of Women and Likelihood of Sexual Aggression. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 38, 734–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, A.; Piff, P.; Mendoza-Denton, R.; Hinshaw, S. The Power of a Label: Mental Illness Diagnoses, Ascribed Humanity, and Social Rejection. J. Couns. Dev. 2011, 94, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrighetto, L.; Baldissarri, C.; Lattanzio, S.; Loughnan, S.; Volpato, C. Human-Itarian Aid? Two Forms of Dehumanization and Willingness to Help After Natural Disasters. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 53, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bastian, B.; Haslam, N. Experiencing Dehumanization: Cognitive and Emotional Effects of Everyday Dehumanization. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 33, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taskin, L.; Parmentier, M.; Stinglhamber, F. The dark side of office designs: Towards de-humanization. New Technol. Work. Employ. 2019, 34, 262–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldissarri, C.; Andrighetto, L.; Volpato, C. When Work Does Not Ennoble Man: Psychological Consequences of Working Objectification. Test. Psychom. Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 2014, 21, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caesens, G.; Stinglhamber, F. The Relationship between Organizational Dehumanization and Outcomes: The Mediating Role of Emotional Exhaustion. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2019, 61, 699–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, K.; Cullen, J. Continuities and Extensions of Ethical Climate Theory: A Meta-Analytic Review. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 69, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simha, A.; Stanusch, A. The effects of ethical climates on trust in supervisor and trust in organization in a Polish context. Manag. Decis. 2015, 53, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosso, C.; Russo, S. The Perception of Instability and Legitimacy of Status Differences Enhances the Infrahumanization Bias among High Status Groups. Eur. J. Psychol. 2019, 15, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Russo, S.; Mosso, C.O. Infrahumanization and Socio-Structural Variables: The Role of Legitimacy, Ingroup Identification, and System Justification Beliefs. Soc. Justice Res. 2019, 32, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.K.; Fruchter, N.; Dabbish, L. Making Decisions from a Distance: The Impact of Technological Mediation on Riskiness and Dehumanization. In Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 14–18 March 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lobchuk, M.M. Concept Analysis of Perspective-Taking: Meeting Informal Caregiver Needs for Communication Competence and Accurate Perception. J. Adv. Nurs. 2006, 54, 330–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaes, J.; Muratore, M. Defensive Dehumanization in the Medical Practice: A Cross-Sectional Study from a Health Care Worker’s Perspective. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 52, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caesens, G.; Stinglhamber, F.; Demoulin, S. Perceived Organizational Support and Employee’s Well-Being: The Mediating Role of Organizational Dehumanization. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2017, 26, 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñiz, J.; Elosua, P.; Hambleton, R.K. International Test Commission Guidelines for Test Translation And Adaptation: Second Edition. Psicothema 2013, 25, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guillemin, F.; Bombardier, C.; Beaton, D. Cross-cultural adaptation of health-related quality of life measures: Literature review and proposed guidelines. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1993, 46, 1417–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaton, D.E.; Bombardier, C.; Guillemin, F.; Ferraz, M.B. Guidelines for the Process of Cross-Cultural Adaptation of Self-Report Measures. Spine 2000, 25, 3186–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Caesens, G.; Nguyen, N.; Stinglhamber, F. Abusive supervision and organizational dehumanization. J. Bus. Psychol. 2018, 34, 709–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.; Stinglhamber, F. Emotional labor and core self-evaluations as mediators between organizational dehumanization and job satisfaction. Curr. Psychol. 2018, 40, 831–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meliá, J.L.; Peiró, J.M. El Cuestionario De Satisfacción S10/12: Estructura Factorial, Fiabilidad y Validez. Rev. Psicol. Trab. Organ. 1989, 4, 179–187. [Google Scholar]

- Meliá, J.L.; Pradilla, J.F.; Martí, N.; Sancerni, M.; Oliver, A.; Tomás, J.M. Estructura Factorial, Fiabilidad y Validez Del Cuestionario De Satisfacción S21/26: Un Instrumento Con Formato Dicotómico Orientado Al Trabajo Profesional. Rev. Psicol. Univ. Tarracon. 1990, 12, 25–39. [Google Scholar]

- Meliá, J.L.; Peiró, J.M.; Calatayud, C. El Cuestionario General De Satisfacción En Organizaciones Laborales: Estudios Factoriales, Fiabilidad y Validez. (Presentación Del Cuestionario S4/82) [The General Satisfaction Questionnaire in Work Organizations: Factorial Studies, Reliability and Validity]. Rev. Filos. Psicol. Cienc. Educ. 1986, 11, 43–78. [Google Scholar]

- Cuddy, A.J.C.; Rock, M.S.; Norton, M.I. Aid in the aftermath of hurricane Katrina: Inferences of secondary emotions and intergroup helping. Group Processes Intergroup Relat. 2017, 10, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rosario-Hernández, E.; Rovira-Millán, L.V. Desarrollo y Validación de la Escala de Ciudadanía Organizacional. Rev. Puertorriqueña Psicol. 2004, 15, 43–78. [Google Scholar]

- Organ, D. Personality and Organizational Citizenship Behavior. J. Manag. 1994, 20, 465–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, W.; Avolio, B.J.; Luthans, F.; May, D.R.; Walumbwa, F. “Can you see the real me?” A self-based model of authentic leader and follower development. Leadersh. Q. 2005, 16, 343–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ilies, R.; Morgeson, F.P.; Nahrgang, J.D. Authentic leadership and eudaemonic well-being: Understanding leader-follower outcomes. Leadersh. Q. 2005, 16, 373–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wong, C.A.; Spence-Laschinger, H.K.; Cummings, G.G. Authentic leadership and nurses’ voice behaviour and perceptions of care quality. J. Nurs. Manag. 2010, 18, 889–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F.; Avolio, B.; Gardner, W.; Wernsing, T.; Peterson, S. Authentic Leadership: Development and Validation of a Theory-Based Measure. J. Manag. 2008, 34, 89–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moriano, J.A.; Molero, F.; Mangin, J. Liderazgo Auténtico. Concepto y Validación Del Cuestionario ALQ En España. Psicothema 2011, 23, 336–341. [Google Scholar]

- Willis, G. Cognitive Interviewing: A Tool for Improving Questionnaire Design; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.-F.; Black, W.-C.; Babin, B.-J.; Anderson, R.-E. Multivariate Data Analysi, 7th ed.; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, L.J.; Ford, L.R.; Nguyen, N.T. Basic and Advanced Measurement Models for Confirmatory Factor Analysis. In Handbook of Research Methods in Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Rogelberg, S., Ed.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2002; pp. 366–389. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cut-Off Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria Versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Modeling 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbuckle, J.L. Users Guide. IBM® SPSS® Amos™ 21. Available online: ftp://public.dhe.ibm.com/software/analytics/spss/documentation/amos/21.0/en/Manuals/IBM_SPSS_Amos_Users_Guide.pdf (accessed on 23 May 2021).

- Shipp, F.; Burns, G.L.; Desmul, C. Construct validity of ADHD-IN, ADHD-HI, ODD toward adults, academic and social competence dimensions with teacher ratings of Thai adolescents: Additional validity for the child and adolescent disruptive behavior inventory. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2010, 32, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.; MacKenzie, S.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro-Loli, J.S.; Domínguez-Lara, S. Propiedades psicométricas de la Escala de Autoeficacia Percibida Específica de Situaciones Académicas en adolescentes peruanos. Psychol. Soc. Educ. 2019, 1, 30–43. [Google Scholar]

- Reise, S.P.; Waller, N.G.; Comrey, A.L. Factor analysis and scale revision. Psychol. Assess. 2000, 12, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominguez-Lara, S. Correlación entre residuales en análisis factorial confirmatorio: Una breve guía para su uso e interpretación. Interacciones 2019, 5, e207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behr, D. Translating questionnaires for cross-national surveys: A description of a genre and its particularities based on the ISO 17100 categorization of translator competences. Transl. Interpret. 2018, 10, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.K.; Van den Broeck, A.; Holman, D. Work design influences: A synthesis of multilevel factors that affect the design of jobs. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2016, 11, 267–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rogala, A.; Cieslak, R. Positive Emotions at Work and Job Crafting: Results from Two Prospective Studies. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmann, B.; Klug, H.; Maier, G.W. The Path Is the Goal: How Transformational Leaders Enhance Followers’ Job Attitudes and Proactive Behavior. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriagada-Venegas, M.; Ramírez-Vielma, R.; Ariño-Mateo, E. El rol moderador de la deshumanización organizacional en la relación entre el liderazgo auténtico y los comportamientos ciudadanos organizacionales. UCJC Bus. Soc. Rev. 2021, 18, 90–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriagada-Venegas, M.; Ariño-Mateo, E.; Ramírez-Vielma, R.; Nazar, G.; Perez-Jorge, D. Authentic leadership and its relationship with job satisfaction: The mediator role of organizational dehumanization. Eur. J. Psychol. in press.

- Arriagada-Venegas, M.; Pérez-Jorge, D.; Ariño-Mateo, E. The Ingroup-Outgroup Relationship Influences Their Humanity: A Moderation Analysis of Status and Gender. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 725898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.; Besson, T.; Stinglhamber, F. Emotional labor: The role of organizational dehumanization. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2022, 27, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stinglhamber, F.; Caesens, G.; Chalmagne, B.; Demoulin, S.; Maurage, P. Leader–member exchange and organizational dehumanization: The role of supervisor’s organizational embodiment. Eur. Manag. J. 2021, 39, 745–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagios, C.; Caesens, G.; Nguyen, N.; Stinglhamber, F. Explaining the negative consequences of organizational dehumanization: The mediating role of psychological need thwarting. J. Pers. Psychol. 2022, 21, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainz, M.; Baldissarri, C. Abusive leadership versus objectifying job features: Factors that influence organizational dehumanization and workers’ self-objectification. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2021, 51, 825–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, A. Impact of Organizational Dehumanization on Employee Perceptions of Mistreatment and their Work Outcomes. Ph.D. Thesis, Capital University, Islamabad, Pakistan, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S.K.; Del Giudice, M.; Tarba, S.Y.; De Bernardi, P. Top Management Team Shared Leadership, Market-Oriented Culture, Innovation Capability, and Firm Performance. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2019, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Pradhan, R.K.; Panigrahy, N.P.; Jena, L.K. Self-efficacy and workplace well-being: Moderating role of sustainability practices. Benchmarking Int. J. 2019, 26, 1692–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Singh, S.K.; Pereira, V.; Leonidou, E. Cause-related marketing and service innovation in emerging country healthcare: Role of service flexibility and service climate. Int. Mark. Rev. 2020, 37, 803–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturman, E.D. Dehumanizing just makes you feel better: The role of cognitive dissonance in dehumanization. J. Soc. Evol. Cult. Psychol. 2012, 6, 527–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.L. Less Than Human: Why We Demean, Enslave, and Exterminate Others; St. Martin’s Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

| Area | Age | Time in the Organization (Years) | Gender (%Man) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | M | SD | M | SD | ||

| Agriculture, livestock, hunting, fishing, and forestry | 5 | 31.40 | 4.93 | 6.83 | 6.55 | 60.0% |

| Mining and quarrying | 2 | 30.00 | 7.07 | 3.17 | 3.06 | 100.0% |

| Manufacturing industry | 73 | 37.95 | 11.18 | 6.55 | 6.93 | 69.9% |

| Electricity, water, or gas supply | 11 | 40.18 | 13.46 | 6.36 | 9.35 | 72.7% |

| Building | 20 | 39.00 | 13.60 | 4.75 | 5.26 | 75.0% |

| Commerce, hotels, and restaurants | 75 | 35.59 | 11.10 | 4.30 | 5.48 | 34.7% |

| Transportation, storage, and communications | 59 | 43.59 | 11.83 | 9.93 | 10.16 | 52.5% |

| Financial services | 24 | 35.71 | 13.34 | 5.65 | 8.20 | 66.7% |

| Public administration and defense | 12 | 39.33 | 10.05 | 7.32 | 6.35 | 66.7% |

| Social services, health, and education | 106 | 40.12 | 10.30 | 7.84 | 7.82 | 30.2% |

| Other services | 35 | 40.29 | 10.18 | 8.15 | 9.42 | 62.9% |

| Total | 422 | 38.96 | 11.40 | 6.95 | 7.86 | 50.7% |

| Minimum | Maximum | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authentic leadership | 0 | 6 | 4.21 | 1.49 |

| Organizational dehumanization | 1 | 7 | 4.41 | 1.39 |

| Job satisfaction | 1.13 | 7 | 5.21 | 1.18 |

| Organizational citizenship behaviors | 2.43 | 6 | 4.76 | 0.56 |

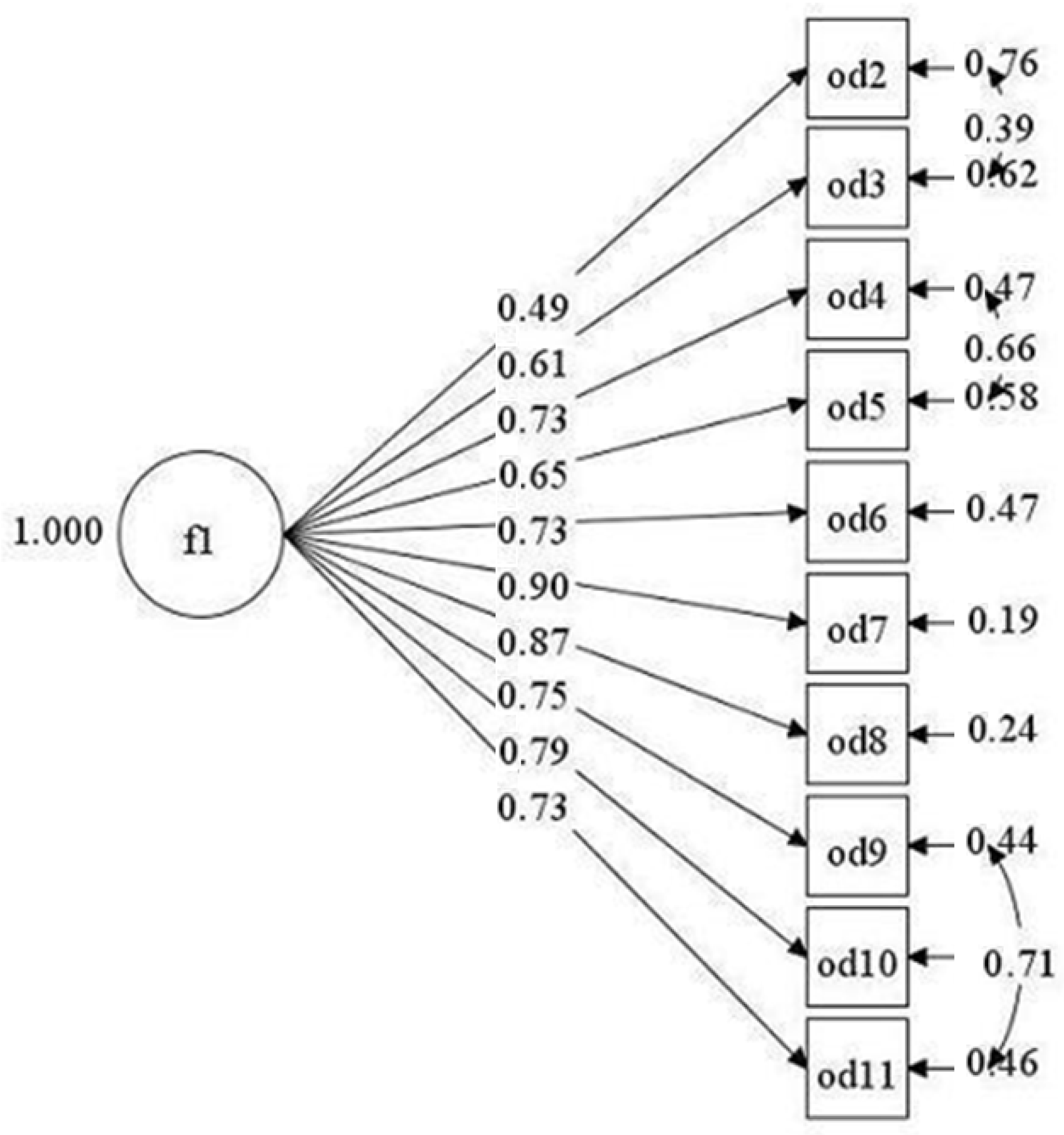

| Item | Factor Loadings | Factor Loadings |

|---|---|---|

| OD 1 | −0.21 * | - |

| OD 2 | 0.49 * | 0.48 * |

| OD 3 | 0.57 * | 0.56 * |

| OD 4 | 0.70 * | 0.71 * |

| OD 5 | 0.69 * | 0.70 * |

| OD 6 | 0.80 * | 0.81 * |

| OD 7 | 0.90 * | 0.90 * |

| OD 8 | 0.89 * | 0.90 * |

| OD 9 | 0.74 * | 0.70 * |

| OD 10 | 0.80 * | 0.77 * |

| OD 11 | 0.74 * | 0.69 * |

| χ2 | df | χ2/df Ratio | SRMR | RMSEA | CFI | TLI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organizational dehumanization | 82.11 | 32 | 2.57 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.93 | 0.90 |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Authentic leadership | (α 0.97) (ω 0.98) | −0.28 ** | 0.61 ** | 0.25 ** |

| 2. Organizational dehumanization | (α 0.92) (ω 0.92) | −0.30 ** | −0.12 * | |

| 3. Job satisfaction | (α 0.96) (ω 0.96) | 0.33 ** | ||

| 4. Organizational citizenship behaviors. | (α 0.84) (ω 0.87) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ariño-Mateo, E.; Ramírez-Vielma, R.; Arriagada-Venegas, M.; Nazar-Carter, G.; Pérez-Jorge, D. Validation of the Organizational Dehumanization Scale in Spanish-Speaking Contexts. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4805. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084805

Ariño-Mateo E, Ramírez-Vielma R, Arriagada-Venegas M, Nazar-Carter G, Pérez-Jorge D. Validation of the Organizational Dehumanization Scale in Spanish-Speaking Contexts. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(8):4805. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084805

Chicago/Turabian StyleAriño-Mateo, Eva, Raúl Ramírez-Vielma, Matías Arriagada-Venegas, Gabriela Nazar-Carter, and David Pérez-Jorge. 2022. "Validation of the Organizational Dehumanization Scale in Spanish-Speaking Contexts" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 8: 4805. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084805

APA StyleAriño-Mateo, E., Ramírez-Vielma, R., Arriagada-Venegas, M., Nazar-Carter, G., & Pérez-Jorge, D. (2022). Validation of the Organizational Dehumanization Scale in Spanish-Speaking Contexts. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(8), 4805. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084805