Representations of Sexuality among Persons with Intellectual Disability, as Perceived by Professionals in Specialized Institutions: A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

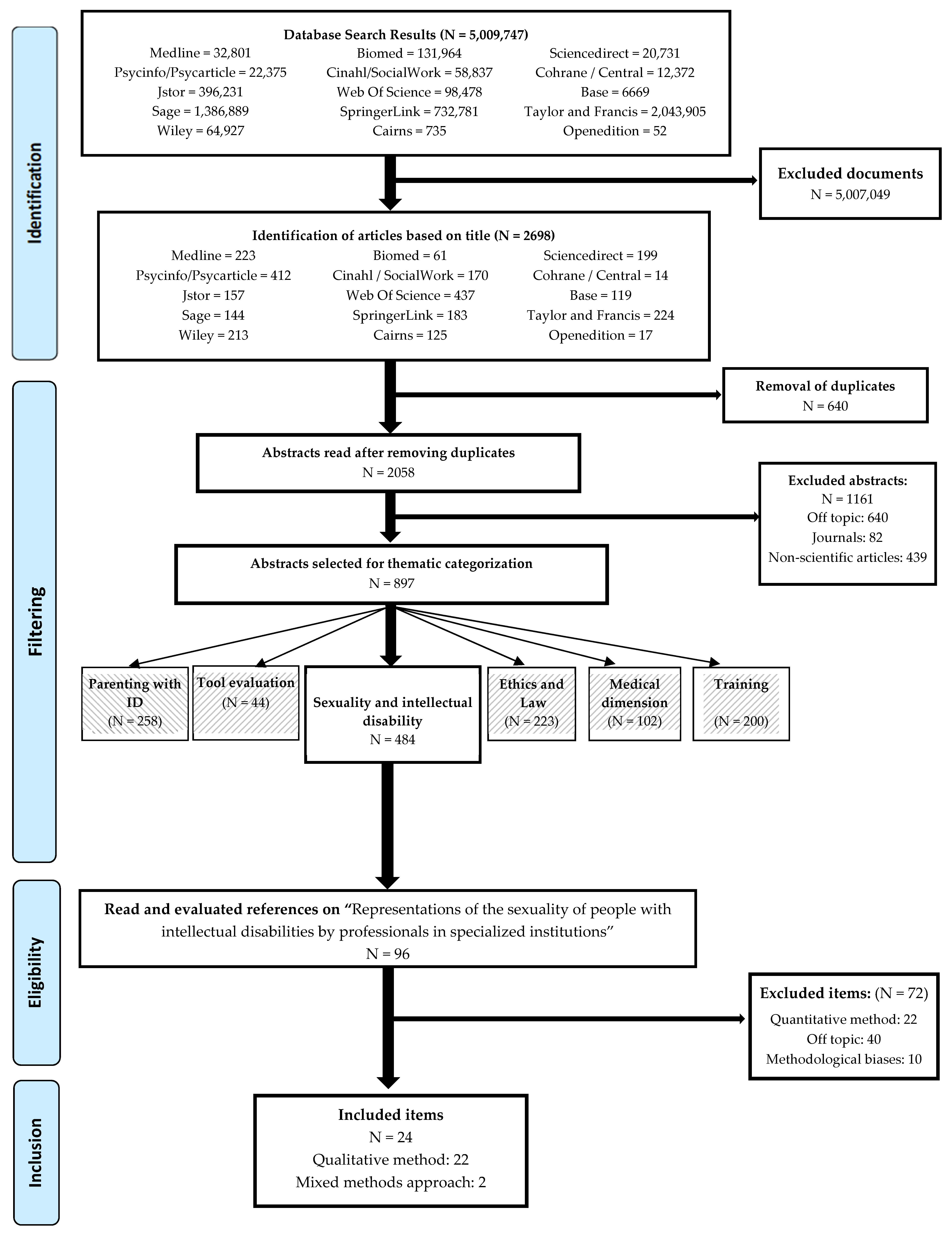

2. Method

2.1. Research Question

2.2. Systematic Review Protocol

2.3. Study Selection

- -

- Some of these focused on professionals working with mentally ill persons with no co-occurrence of ID.

- -

- Other studies focused on the representations of the families of individuals with ID, on these people’s representations of contraception, on students’ representations, or on representations on the subject of the general population.

- -

- Several articles did not directly address the issue of sexuality, but rather focused on related themes: parenthood, general ethical issues, or an analysis of scholarly writings.

- -

- Others focused on the sexuality of adolescents with intellectual disability.

3. Results of the Systematic Review

3.1. Overview of the Corpus

3.2. Thematic Analysis

- -

- Professionals’ representations of gender, sexuality, and consent;

- -

- Professionals’ perceptions of their role in supporting peoples’ sex lives;

- -

- The construction of professionals’ representations of individuals’ sex lives.

3.2.1. Professionals’ Representations of Gender, Sexuality, and Consent

3.2.2. Professionals’ Perceptions of Their Role in Supporting People’s Sex Lives

3.2.3. The Construction of Professionals’ Representations of People’s Sex Lives

- -

- Not all professionals in a team are trained;

- -

- The management does not reorganize the center to allow a genuine application of what is learned in training (rooms for couples, intimate spaces to allow people to meet and to have sexual relationships, etc.);

- -

- The social–cultural context still stigmatizes sexuality and disability, especially because of the fear of sexual assault [28].

- -

- Discourse of protection vs. discourse of normalization;

- -

- Biologizing discourses on sexuality, where sex is differentiated from intimacy and pleasure, discourses that contrast with the needs expressed by people seeking to encounter the other;

- -

- Professional discourses in terms of competences, even though few competences are clearly identifiable and explicable in this field. Social–emotional needs and sexual desire are, by their very nature, complex. They primarily involve relational skills, i.e., collaborating with people, and are determined by the professionals’ intuitions and ways of being [24].

4. Discussion

- -

- A perception of the sexuality of people struggling with gender stereotypes;

- -

- Difficulty thinking positively about the aspects of people’s lives as a couple or as a family;

- -

- The feeling that they must protect individuals under their care from great violence.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. The Standard Rules on the Equalization of Opportunities for Persons with Disabilities; United Nations, Disabled Persons Unit, & United Nations, Department of Public Information: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Stancliffe, R.J.; Wehmeyer, M.L.; Shogren, K.A.; Abery, B.H. (Eds.) Choice, Preference, and Disability: Promoting Self-Determination across the Lifespan; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; ISBN 978-3-030-35682-8. [Google Scholar]

- Aunos, M.; Feldman, M.A. Attitudes towards Sexuality, Sterilization and Parenting Rights of Persons with Intellectual Disabilities. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2002, 15, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.; McCann, E. The Views and Experiences of Families and Direct Care Support Workers Regarding the Expression of Sexuality by Adults with Intellectual Disabilities: A Narrative Review of the International Research Evidence. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2019, 90, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whittle, C.; Butler, C. Sexuality in the Lives of People with Intellectual Disabilities: A Meta-Ethnographic Synthesis of Qualitative Studies. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2018, 75, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giami, A. Sexualité et handicaps: De la stérilisation eugénique à la reconnaissance des droits sexuels (1980–2016). Sexologies 2016, 25, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaginay, D. Corps handicapé, sexualité, loi et institution. La Lettre de L’enfance et de L’adolescence 2008, 72, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giulio, G. Sexuality and People Living with Physical or Developmental Disabilities: A Review of Key Issues. Can. J. Hum. Sex. 2003, 12, 53–68. [Google Scholar]

- Giami, A. La médicalisation de la sexualité: Aspects sociologiques et historiques. Andrologie 1998, 8, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Giami, A.; Vaginay, D.; Balandier, M. Vie Effective et Sexualité en ESSMS: De la Prévention des Conduites à Risques à L’accompagnement à la Parentalité. Available online: https://www.actif-online.com/publications/les-cahiers-de-lactif/le-dernier-numero/vie-affective-et-sexualite-en-essms-de-la-prevention-des-conduites-a-risques-a-laccompagnement-a.html (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- Debest, C.; Mazuy, M.; Fecond, L.D.L. Rester sans enfant: Un choix de vie à contre-courant. Popul. Soc. 2014, 508, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moher, D.; Altman, D.G.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J. PRISMA Statement. Epidemiology 2011, 22, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- International Classification of Diseases (ICD). Available online: https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/classification-of-diseases (accessed on 29 March 2022).

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-0-89042-554-1. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, S.; Vecchio, M.; Craig, J.C.; Tonelli, M.; Johnson, D.W.; Nicolucci, A.; Pellegrini, F.; Saglimbene, V.; Logroscino, G.; Fishbane, S.; et al. Prevalence of Depression in Chronic Kidney Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Kidney Int. 2013, 84, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- CASP. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). Qual. Res. Checkl. 2017, 31, 449. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, V.R.; Stancliffe, R.J.; Broom, A.; Wilson, N.J. Barriers to Sexual Health Provision for People with Intellectual Disability: A Disability Service Provider and Clinician Perspective. J. Intell. Dev. Disabil. 2014, 39, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aderemi, T.J. Teachers’ Perspectives on Sexuality and Sexuality Education of Learners with Intellectual Disabilities in Nigeria. Sex. Disabil. 2014, 32, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, C.; Terry, L.; Popple, K. Supporting People with Learning Disabilities to Make and Maintain Intimate Relationships. Tizard Learn. Disabil. Rev. 2017, 22, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brantlinger, E. Professionals’ Attitudes toward the Sterilization of People with Disabilities. J. Assoc. Pers. Sev. Handicap. 1992, 17, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.D.; Pirtle, T. Beliefs of Professional and Family Caregivers about the Sexuality of Individuals with Intellectual Disabilities: Examining Beliefs Using a Q-Methodology Approach. Sex Educ. 2008, 8, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caresmel, N. Cadre légal et professionnel d’une pratique sexuelle. Le Sociographe 2014, 47, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chivers, J.; Mathieson, S. Training in Sexuality and Relationships: An Australian Model. Sex. Disabil. 2000, 18, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćwirynkało, K.; Byra, S.; Żyta, A. Sexuality of Adults with Intellectual Disabilities as Described by Support Staff Workers. Hrvatska Revija Za Rehabilitacijska Istraživanja 2017, 53, 77–87. [Google Scholar]

- Eastgate, G.; Scheermeyer, E.; van Driel, M.L.; Lennox, N. Intellectual Disability, Sexuality and Sexual Abuse Prevention A Study of Family Members and Support Workers. Aust. Fam. Physician 2012, 41, 135–139. [Google Scholar]

- Grace, N.; Greenhill, B.; Withers, P. “They Just Said Inappropriate Contact”. What Do Service Users Hear When Staff Talk about Sex and Relationships? J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2017, 33, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanass-Hancock, J.; Nene, S.; Johns, R.; Chappell, P. The Impact of Contextual Factors on Comprehensive Sexuality Education for Learners with Intellectual Disabilities in South Africa. Sex. Disabil. 2018, 36, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaeser, F. Can People with Severe Mental Retardation Consent to Mutual Sex? Sex. Disabil. 1992, 10, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafferty, A.; McConkey, R.; Simpson, A. Reducing the Barriers to Relationships and Sexuality Education for Persons with Intellectual Disabilities. J. Intell. Disabil. 2012, 16, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lofgren-Martenson, L. “May I?”—About Sexuality and Love in the New Generation with Intellectual Disabilities. Sex. Disabil. 2004, 22, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, K.; Gleeson, K.; Holmes, N. Support Workers’ Understanding of Their Role Supporting the Sexuality of People with Learning Disabilities. Br. J. Learn. Disabil. 2019, 47, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pariseau-Legault, P.; Holmes, D.; Ouellet, G.; Vallée-Ouimet, S. An Ethical Inquiry of Support Workers’ Experiences Related to Sexuality in the Context of Intellectual Disabilities in Quebec, Canada. Br. J. Learn. Disabil. 2019, 47, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohleder, P.; Swartz, L. Providing Sex Education to Persons with Learning Disabilities in the Era of HIV/AIDS Tensions between Discourses of Human Rights and Restriction. J. Health Psychol. 2009, 14, 601–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, M.; Corbett, J.; Newton, J.; Roy, A. Women with a Learning Disability (Mental Handicap) Referred for Sterilisation; Assessment and Follow Up. J. Obstetr. Gynaecol. 1993, 13, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaria, É. Sexualité et contraception en institutions spécialisées: Le besoin de devenir adulte. La Revue Internationale de L’éducation Familiale 2008, 24, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, V.R.; Stancliffe, R.J.; Broom, A.; Wilson, N.J. Clinicians’ Use of Sexual Knowledge Assessment Tools for People with Intellectual Disability. J. Intell. Dev. Disabil. 2016, 41, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkenfeld, B.F.; Ballan, M.S. Educators’ Attitudes and Beliefs Towards the Sexuality of Individuals with Developmental Disabilities. Sex. Disabil. 2011, 29, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yool, L.; Langdon, P.E.; Garner, K. The Attitudes of Medium-Secure Unit Staff toward the Sexuality of Adults with Learning Disabilities. Sex. Disabil. 2003, 21, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, R.; Gore, N.; McCarthy, M. Staff Attitudes towards Sexuality in Relation to Gender of People with Intellectual Disability: A Qualitative Study. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2012, 37, 343–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szollos, A.A.; McCabe, M.P. The Sexuality of People with Mild Intellectual Disability: Perceptions of Clients and Caregivers. Aust. N. Z. J. Dev. Disabil. 1995, 20, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, Y.-C.; Lu, Z.J.; Lin, C.-J. Comparison of Attitudes to the Sexual Health of Men and Women with Intellectual Disability among Parents, Professionals, and University Students. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2018, 43, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuskelly, M.; Bryde, R. Attitudes towards the Sexuality of Adults with an Intellectual Disability: Parents, Support Staff, and a Community Sample. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2004, 29, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, L.; Chambers, B. Intellectual Disability and Sexuality: Attitudes of Disability Support Staff and Leisure Industry Employees. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2010, 35, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, M. An Evaluation of Staff Attitudes towards the Sexual Activity of People with Learning Disabilities. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 1998, 61, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J.L.; MacDonald, R.A.R.; Brown, G.; Levenson, V.L. Staff Attitudes towards the Sexuality of Individuals with Learning Disabilities: A Service-Related Study of Organisational Policies. Br. J. Learn. Disabil. 1999, 27, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J.L.; MacDonald, R.A.R. Staff Attitudes towards Individuals with Learning Disabilities and Aids: The Role of Attitudes towards Client Sexuality and the Issue of Mandatory Testing for HIV Infection. Ment. Handicap Res. 1995, 8, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, D.; McConkey, R. Staff Attitudes to Sexuality and People with Intellectual Disabilities. Ir. J. Psychol. 2000, 21, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzo, G.; Nota, L.; Soresi, S.; Ferrari, L.; Minnes, P. Attitudes of Social Service Providers towards the Sexuality of Individuals with Intellectual Disability. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2007, 20, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.S.; McGuire, B.E.; Healy, E.; Carley, S.N. Sexuality and Personal Relationships for People with an Intellectual Disability. Part II: Staff and Family Carer Perspectives. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2009, 53, 913–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieve, A.; McLaren, S.; Lindsay, W.; Culling, E. Staff Attitudes towards the Sexuality of People with Learning Disabilities: A Comparison of Different Professional Groups and Residential Facilities. Br. J. Learn. Disabil. 2009, 37, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazukauskas, K.A.; Lam, C.S. Disability and Sexuality: Knowledge, Attitudes, and Level of Comfort Among Certified Rehabilitation Counselors. Rehabil. Couns. Bull. 2010, 54, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConkey, R.; Ryan, D. Experiences of Staff in Dealing with Client Sexuality in Services for Teenagers and Adults with Intellectual Disability. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2001, 45, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fustier, P. Le Travail d’équipe En Institution: Clinique de L’institution Médico-Sociale et Psychiatrique; Dunod: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolle, O.; Kaës, R. L’institution en Héritage: Mythes de Fondation, Transmissions, Transformations; Dunod: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cicconne, A. La Violence Dans Le Soin; Dunod: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lumley, V.A.; Scotti, J.R. Supporting the Sexuality of Adults with Mental Retardation: Current Status and Future Directions. J. Posit. Behav. Interv. 2001, 3, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaginay, D. Sexualité des personnes déficientes intellectuelles. Prat. Sante Ment. 2017, 63, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballan, M. 2001 Parents as Sexuality Educators for Their Children with Developmental Disabilities. Siecus Rep. 2004, 29, 14–19. [Google Scholar]

| Study Citation and Country | Aim | Readership | Method of Data Collection | Key Findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | [18] Thompson, V.R. et al. Australia | To examine the barriers to sexual health provision of people with ID as experienced by disability service providers and clinicians. | Eight managers (four men, four women) and 23 clinicians (8 men, 15 women). | Semi-structured interviews carried out in two phases, with managers of services receiving people with disabilities by telephone, then with professionals in the field face to face. Both are analyzed with constructivist grounded theory. | The difficulties identified in the research have been grouped into three broad categories: administration (lack of funding and lack of policy guidelines), attitudes (myths about the sexual health) and experiences (lack of staff training). |

| 2 | [19] Aderemi, T.J. Nigeria | This article reports on teachers’ views on the sexuality of Nigerian learners with intellectual disabilities and their awareness of their risk of HIV infection. | Twelve specialized teachers (nine women and three men) working with people with ID. The age of the people with ID with whom they work is not specified. | Semi-structured interviews with 12 specialized teachers (9 women and 3 men) working with people with ID. Analyzed with interpretative phenomenological analysis. | Teachers feel able to teach about sexuality, they perceive sexuality as negative. They are concerned about the risk of rape of women with ID, and they have the belief, shared by families, that a child from a woman with ID would help the family recover from the disappointment of having a child with ID. |

| 3 | [20] Bates, C., et al. United Kingdom | To understand some of the barriers that people with learning disabilities face in relationships and to consider what changes professionals could make to address these. | Eleven people, aged over 18, identified as having an ID. | Case studies illustrating a number of themes relating to the support that people with learning disabilities received and needed from staff to develop and maintain relationships. | People with learning disabilities continue to experience barriers with regards to relationships. Their rights and choices are not always respected and a climate of risk aversion persists in areas such as sexual relationships. The research highlighted the balancing act staff must engage in to ensure that they remain supportive without being controlling or overprotective of individuals in relationships. |

| 4 | [21] Brantlinger, E. United States | To explore the attitudes of people in various professional fields toward sexuality, sterilization, and people with disabilities. | Legal professional N = 14 Medical professional N = 8 Professional of family planning agency N = 4 Professional of department of Public Welfare N = 3 Professional of developmental disabilities agency N = 13 Educators N = 8 | Semi-structured interviews were used to explore the attitudes of legal, medical, social welfare, development agency and education professionals towards sterilization of people with disabilities. | Most professionals had been involved in some capacity with sterilization cases of people with disabilities and were concerned about present practices. |

| 5 | [22] Brown, R.D.; Pirtle, T. United States | To describe the perceptions of involved adults concerning the sexuality of individuals with intellectual disabilities. | Forty individuals who provide direct care or instruction to individuals with intellectual disabilities completed the 36-item Q-sort. | The Q-methodology was chosen. This method combines qualitative strategies with quantitative and qualitative analysis. | An understanding of their feelings allows caregivers and educators to react to individuals under their care in a professional manner, even when the situation may challenge their personal beliefs. For the working professional, communication could also be enhanced with an understanding of commonly held beliefs and opinions. The understanding of others’ beliefs could provide a frame of reference under which communication can proceed with parents, teachers, and the individual with intellectual disabilities. |

| 6 | [23] Caresmel, N. France | To describe how professionals in the medico-social sector see the sexuality of people with intellectual disabilities. | 39 professionals working in institutions for people with intellectual disabilities. | Semi-structured interviews were used with professionals. Social representation theory was used to analyze the data. | The results show a strong discrepancy between a representation conveying a desire for action, a recognition of the reality of manifestations, demands and limits associated in particular with the absence of an explicit institutional framework, and different family representations. |

| 7 | [24] Chivers, J.; Mathieson, S. Australia | This article examines some of the dominant discourses that impacted on the process of developing a curriculum for staff working with people with an ID. | Guides to publishing a training course by two professionals in the field. | Analysis of dominant discourses on sexuality in professional training programs. | Constructions of sexuality as being solely a biological function, sex as dangerous, and sex as penetration are challenged, as are some of the dominant discourses of learning. |

| 8 | [25] Ćwirynkało, K. et al. Poland | To know how professionals working with adults with ID view the sexuality and intimate relationships of adults with ID. | Interviews with 16 professionals from several day and residential centers. | The authors conducted 16 interviews with professionals from several day and residential centers. The data were analyzed using the phenomenographic method. | First, professionals shape the quality of life of the clients where they work. The attitudes of caregivers and support workers directly influence people with ID. Second, the attitudes of professionals definitely affect the relationships of those professionals with their clients’ parents or caregivers. Last but not least, the existence of negative attitudes and misconceptions about the sexuality of individuals with ID among professionals can lead those individuals to internalize such attitudes and misconceptions. |

| 9 | [26] Eastgate, Gillian; Scheermeyer, Elly; van Driel, Mieke L.; Lennox, Nick Autralia | This study sought information from people involved in the care of adults with ID regarding how they supported them in the areas of sexuality, relationships and abuse prevention. | Twenty-eight family members and paid support workers caring for adults with intellectual disabilities. | Semi-structured interviews and focus groups were held with 28 family members and paid support workers caring for adults with intellectual disabilities. | Major themes emerging included views on sexuality and ID, consent and legal issues, relationships, sexual knowledge and education, disempowerment, exploitation and abuse, sexual health, and parenting. |

| 10 | [27] Grace, N. et al. United Kingdom | This study explores representations of staff discourses about the sexuality and intimate relationships of patients with intellectual disabilities. | Interviews were conducted with eight individuals with ID. | Semi-structured interviews were carried out with individuals with ID and analyzed using the principles of critical discourse analysis. | Discourses around sex appear to serve the interests of staff and the hospital, while being restrictive and often incomprehensible to service users. Implications for service development, and future research directions, are considered in the context of “Transforming Care”. |

| 11 | [28] Hanass-Hancock, J. et al. South Africa | The paper discusses the educators’ understanding and experiences of using an innovative sexuality training approach for educators of learners with diverse disabilities (Breaking the Silence). | A total of 13 educators (including 9 teachers, 2 psychologists, and 2 principals) were provided with the training and resources of the Breaking the Silence approach. | Following a 12-month implementation period, in-depth interviews were conducted with the 13 educators. | Although educators were able to implement parts of the approach, contextual factors impacted the degree of implementation. These factors were related to perceptions of socio-cultural norms, interpersonal engagement with peers and management, the structural environment of school settings, and the wider community setting. Educators began to address cultural taboos related to talking about sexuality, but were challenged by untrained staff and the larger socio-cultural context, which includes a heighted risk of sexual violence against their learners. |

| 12 | [29] Keaser, F., United States | This article examines, in detail, all aspects of consent and ways for determining consent as well as the responsibilities an interdisciplinary team has for managing mutual sex behaviors. | Team discussions generated by the situation of two men who want to have a sexual relationship in a care home. | Case study. | It advocates for a new standard of competence in sexual relations between two severely mentally retarded persons to be established. |

| 13 | [30] Lafferty, A. et al. Ireland | To understand how the barriers of the attitudes and perceptions of family carers, frontline support workers and professional staff toward the participation of persons with intellectual disabilities in relationships and sexuality education (RSE) might be reduced. | Study included 22 carers, 24 professionals from various disciplines working in the field of intellectual disabilities: 8 learning disability nurses, 5 social workers, but including also educationalists, social care managers and other healthcare professionals such as a psychiatrist, a psychologist and an occupational therapist; 24 frontline staff recruited from social care day centers and supported accommodation services across Northern Ireland. | 19 interviews were conducted with 22 carers. 24 individual interviews with professionals. Five focus groups were held with 24 frontline staff. The information gathered from the group and individual interviews was analyzed using thematic content analysis. | Although there was agreement on the need for RSE, four barriers were commonly reported: the need to protect vulnerable persons; the lack of training; the scarcity of educational resources; and cultural prohibitions. The impact of these barriers could be lessened through partnership working across these groups involving the provision of training and information about RSE, the development of risk management procedures and the empowerment of people with intellectual disabilities. |

| 14 | [31] Lofgren-Martenson, L. Sweden | The aim of the article is to identify, describe and understand the opportunities and hindrances for young people with intellectual disabilities in forming relationships and expressing sexuality and love. | Study included 13 youngsters with ID, 13 staff members, and 11 parents, but also observation of dance gatherings. | Fourteen participant observations at dances geared towards youths with ID and qualitative interviews with youngsters, staff members and parents. Thematic and ethnographic analysis (cultural and historical context) using symbolic interactionism as a framework for analyzing observations in people’s dance venues. Dimension of analysis of the social construction of sexuality. | The results show a big variation of sexual conduct, where intercourse seems to be quite unusual. The study also shows that staff and parents feel responsibility for the youngsters’ sexuality and often act disciplinary as ‘new institutional walls’, while the youngsters develop different social strategies to cope with the surroundings. It seems clear that staff need more guidance and education about sexuality and disability in their social interaction with a new generation of people with ID. |

| 15 | [32] Maguire, K. et al. United Kingdom | This research aimed to explore support workers’ understanding of their role supporting the sexuality of adults with learning disabilities. | Six support workers from supported living services. | Six support workers were interviewed about their role. Data were analyzed using interpretative phenomenological analysis. | Support workers held conflicting beliefs and emotions about their role supporting sexuality. This was interpreted as creating an ambivalence that could result in support workers distancing themselves from an active role in supporting sexuality. Support workers may inadvertently express an understanding of their role that may be consistent with negative and limiting discourses about the sexuality of adults with learning disabilities. |

| 16 | [33] Pariseau-Legault, P. Canada | To explore the ethical implications of support workers’ experiences concerning sexuality in the context of intellectual disabilities in everyday practice. | Six support workers. | In-depth individual interviews analyzed thanks to critical phenomenology. | Support workers’ experiences related to sexuality in the context of intellectual disabilities are influenced by how they define their role in a clinical context. This role is influenced by how affective and sexual life is included in practices, local policies, and interdisciplinary work. Despite positive attitudinal changes, sexuality is still regarded as a sensitive topic capable of endangering both service users and support workers. |

| 17 | [34] Rohleder, P.; Swartz, L. United Kingdom | This article explores the challenges expressed by participants who provide sex education for persons with learning disabilities. | Four family planning social workers and three specialized teachers working at two different schools for learners with learning disabilities. | Thematic analysis of four in-depth interviews and of a group interview. | The findings reveal a tension between a human rights discourse and a discourse of restriction of sexual behaviors. |

| 18 | [35] Roy, M. et al. United Kingdom | This article examines the reasons for the gynecological consultation for sterilization of women with a learning disability (mental handicap). | Nine girls and women with a learning disability (mental handicap) and their caregivers. | Semi structured interviews with the girls and women with a learning disability. All professionals involved were interviewed individually. The interviews were analyzed using content analysis. | Most referrals were found to be initiated by the patient’s mother, where her own contraceptive history was found to be important in her assessment of the benefits of sterilization. It was felt that a comprehensive assessment and interviewing multiple informants enabled a more accurate assessment to be made about the woman’s ability to consent, and if she were unable to do so, then to assess her best interests. Most of the cases were found to be suitable for reversible noninvasive means of contraception. |

| 19 | [36] Santamaria, E. France | To question the recognition of the passage to adulthood of people with mental disabilities living in specialized institutions. | The director, psychologists, and educator of a medical-educational institute for people with mental disabilities in France. | Three-year observation of the daily life of the institution by participating in the activities of the professionals and the users, the times of meetings reserved for the employees or the meetings with the parents. Thirty one-hour semi-directive interviews with the director of the institution, psychologists, and some educators analyzed with thematic content analysis. | The topic of sexuality is a passionate one in institutions, involving a lot of difficulties. Educators must address sexuality issues to the same extent as they address knowledge of the body or the importance of nutrition. There are tensions and negotiations between the institution and the families (particularly with regard to contraception). It is important to break down the isolation of institutions and to offer training to professionals and build new projects together. Education and awareness work are necessary to change the way people with ID are perceived. |

| 20 | [37] Thompson, V.R. et al. Australia | This paper examines how the assessment tools clinicians are using have been developed to assess the sexual knowledge of people with ID. | Twenty-three clinicians using sexual knowledge assessment tools, working directly with people with ID in relation to their sexual health, some directly employed by disability service providers (N = 19) or in private practice (N = 4). A range of disability programs were represented, including residential (N = 6), day programs (N = 4), and behavioral support (N = 9). | Semi structured qualitative interviews analyzed with a constructivist grounded theory approach. | Assessment of sexual knowledge is not routine in disability service provision. Sexual knowledge is typically only assessed when there has been an incident of problematic sexualized behavior. This reactive approach perpetuates a pathological sexual health discourse. Clinicians also reported that the tools have gaps and are not fully meeting their needs or the needs of people with ID. |

| 21 | [38] Wilkenfeld, B.F. et al. United States | This study presents educators’ attitudes and beliefs towards the sexuality of adolescents and adults with developmental disabilities. | Five teachers in a school program and five instructors in an adult day services program at an educational facility for individuals with medically complex developmental disabilities. | Open-ended, structured interviews analyzed with content analysis coding. | Results indicate that educators hold a positive view towards providing sexuality education and access to sexual expression for persons with developmental disabilities. Educators viewed sexuality as a basic human right, yet expressed concerns regarding capacity to consent to and facilitation of sexual activity. This study helps to understand barriers preventing the delivery of sexuality education to this underserved population. |

| 22 | [39] Yool, L. et al. United Kingdom | The attitudes of staff toward the sexuality of adults with learning disabilities within a medium-secure hospital within the United Kingdom were examined using qualitative research methods. | Four full-time staff members: consulting psychiatrist, long-term care worker, advocacy worker and domestic staff member. | Interviews were transcribed and analyzed using a method adapted from phenomenology. | The analysis revealed that staff members generally held liberal attitudes with respect to sexuality and masturbation. However, with respect to sexual intercourse, homosexual relationships, and the involvement of adults with learning disabilities in decisions regarding their own sexuality, a less liberal attitude was detected. Concern was also noted with respect to the attitudes of female staff members towards the sexuality of adults with learning disabilities who have committed sexual offenses. Training issues were also identified and implications for the service were discussed. |

| 23 | [40] Young, R. et al. United Kingdom | To examine whether gender of people with ID affects staff attitudes regarding the sexuality of people with ID. | Ten staff members of specialized services for people with ID. | Semi structured interviews were completed with 10 staff members and analyzed using thematic analysis. | The study indicates unfavorable attitudes towards sexuality in individuals with ID that correlate with traditional, restricted gender stereotypes. The identification of these themes highlights the importance of considering gender when supporting the sexuality of people with ID. |

| 24 | [41] Szollos, A.A.; McCabe, M.P. Australia | This study compares the sexual and relational knowledge, experience, feelings and needs of people with ID with the perception of their caregivers and the knowledge and experience of people without ID. | The sexuality of 25 individuals with mild ID was assessed based on interviews that addressed their knowledge, experience, feelings, and needs. Compared to 39 college students and 10 care staff. | Data on the sexuality of a group of people with mild ID were obtained by interviewing them directly thanks to the Measure to Assess Sexual and Relational Knowledge, Experience, Feelings and Needs (Sex Ken-ID), and then comparing their responses with the perceptions of their caregivers, as well as to data collected from a group of people without ID. | Care staff consistently overestimated the responses of their clients, whom they perceived to be more knowledgeable and experienced, have more positive feelings, and a greater need to know than was indicated by the clients themselves. The group without ID demonstrated a higher level of sex knowledge and reported greater interactive sexual experience than the people with ID. The exceptions to this were that the latter group had experienced higher levels of sexual abuse, and reported equal frequencies of same-sex experiences. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guenoun, T.; Smaniotto, B.; Clesse, C.; Mauran-Mignorat, M.; Veyron-Lacroix, E.; Ciccone, A.; Essadek, A. Representations of Sexuality among Persons with Intellectual Disability, as Perceived by Professionals in Specialized Institutions: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4771. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084771

Guenoun T, Smaniotto B, Clesse C, Mauran-Mignorat M, Veyron-Lacroix E, Ciccone A, Essadek A. Representations of Sexuality among Persons with Intellectual Disability, as Perceived by Professionals in Specialized Institutions: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(8):4771. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084771

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuenoun, Tamara, Barbara Smaniotto, Christophe Clesse, Marion Mauran-Mignorat, Estelle Veyron-Lacroix, Albert Ciccone, and Aziz Essadek. 2022. "Representations of Sexuality among Persons with Intellectual Disability, as Perceived by Professionals in Specialized Institutions: A Systematic Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 8: 4771. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084771

APA StyleGuenoun, T., Smaniotto, B., Clesse, C., Mauran-Mignorat, M., Veyron-Lacroix, E., Ciccone, A., & Essadek, A. (2022). Representations of Sexuality among Persons with Intellectual Disability, as Perceived by Professionals in Specialized Institutions: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(8), 4771. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084771