Temporal Dimensions of Job Quality and Gender: Exploring Differences in the Associations of Working Time and Health between Women and Men

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

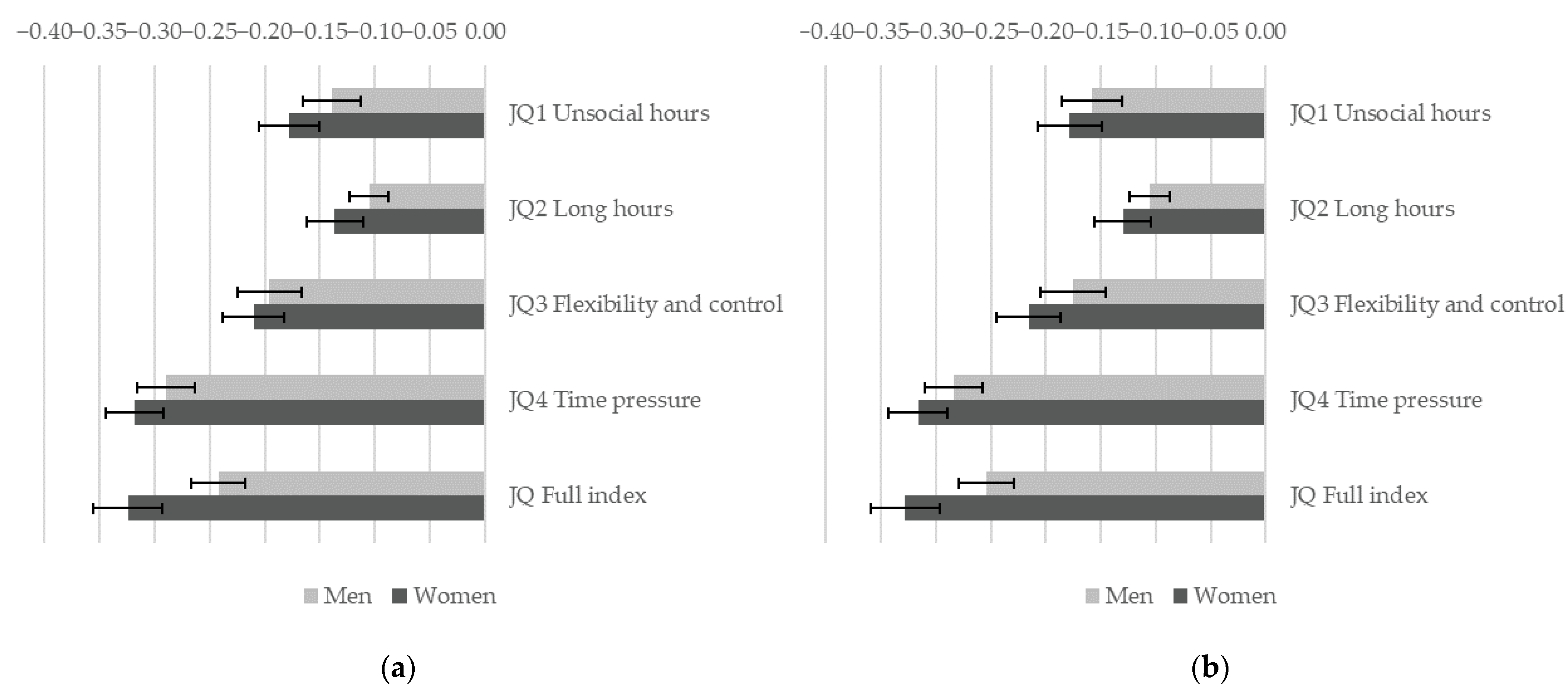

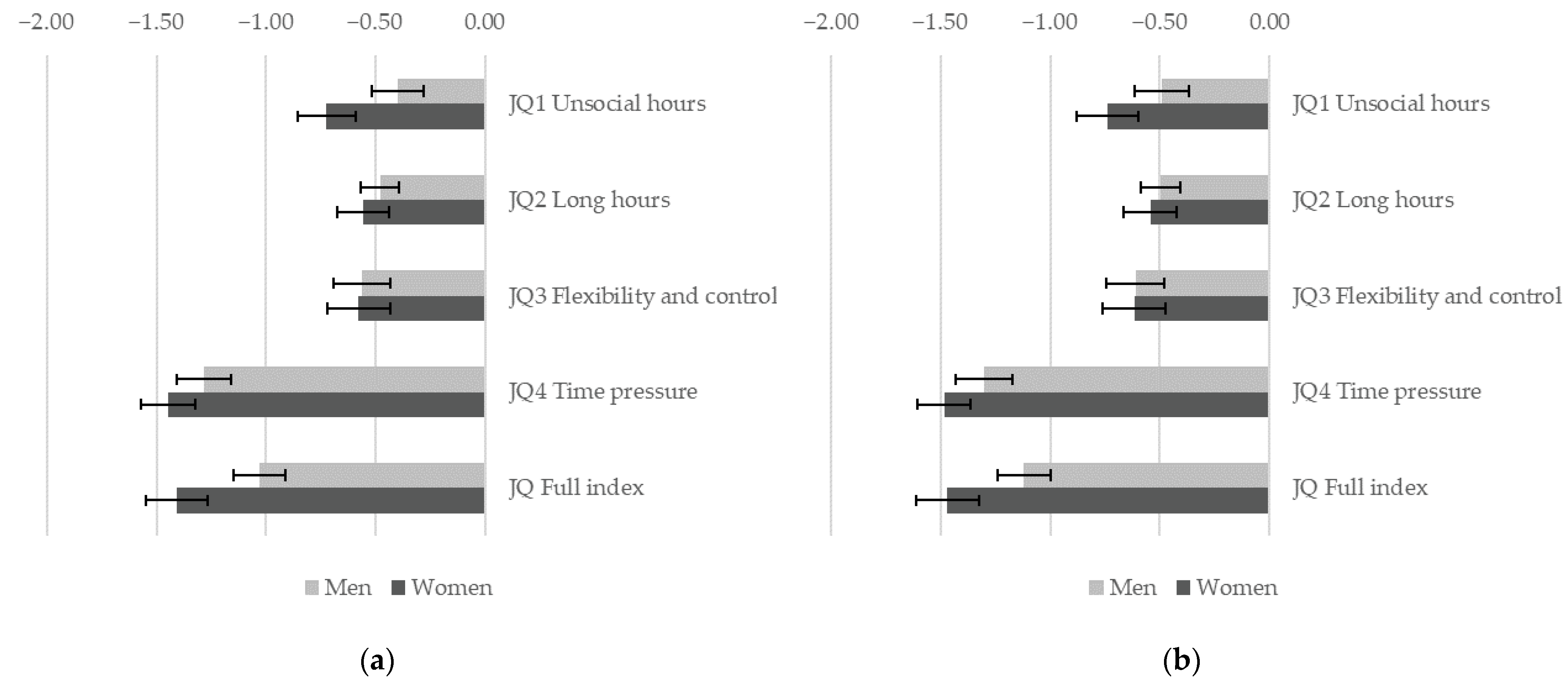

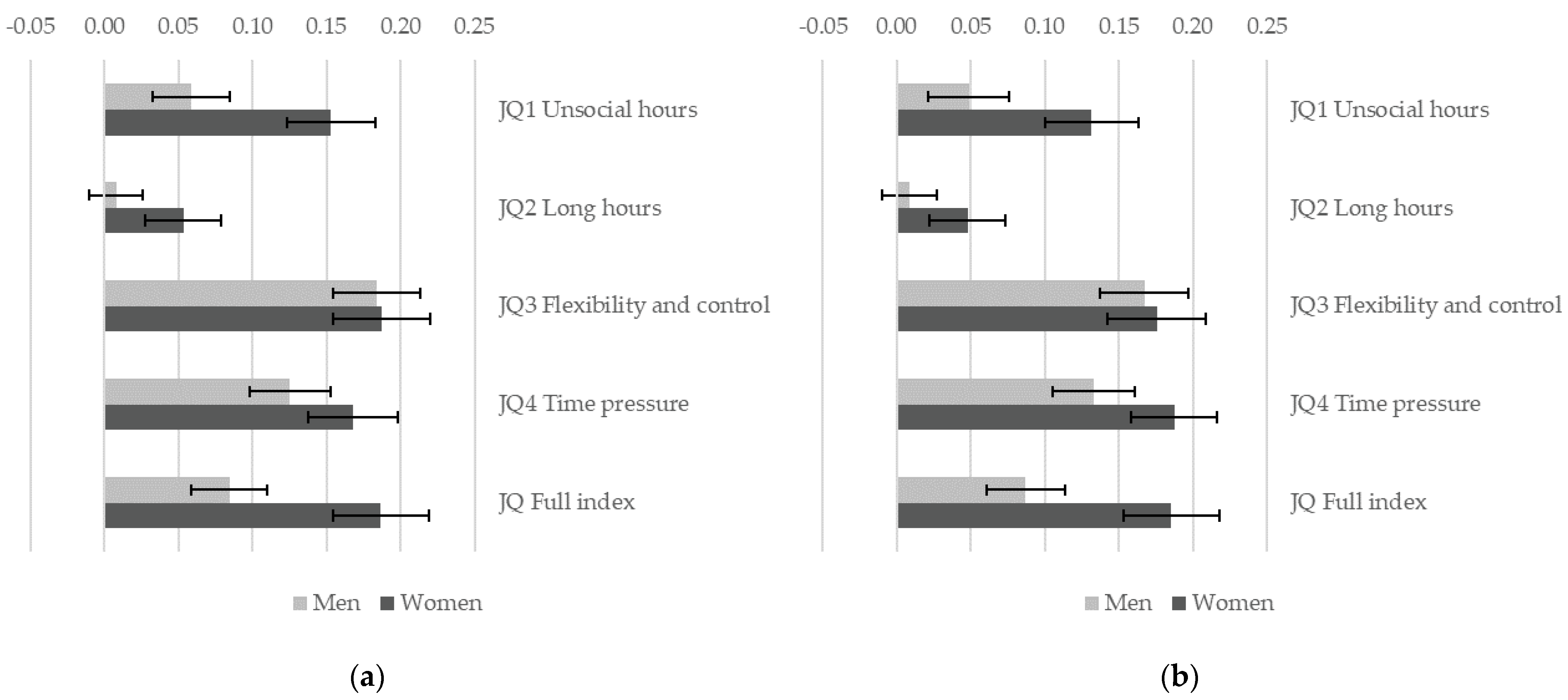

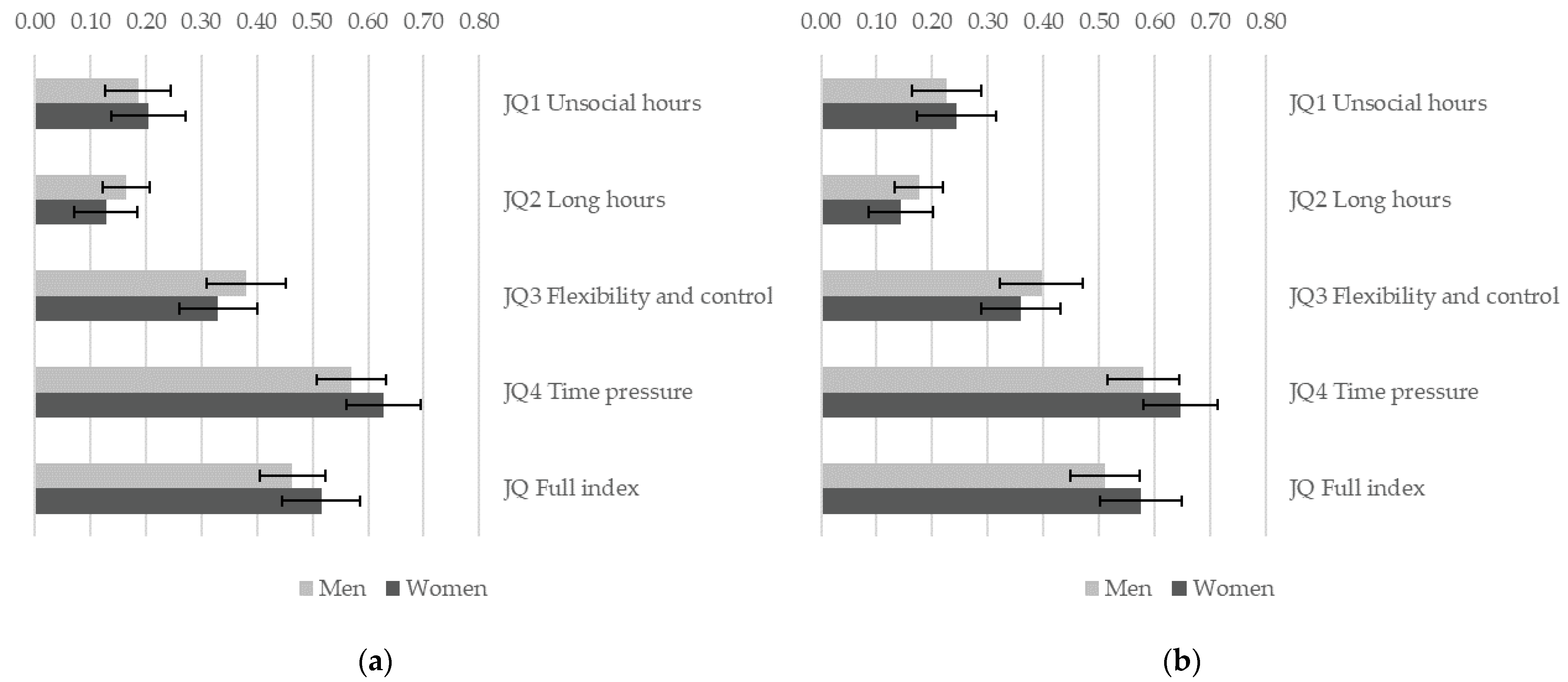

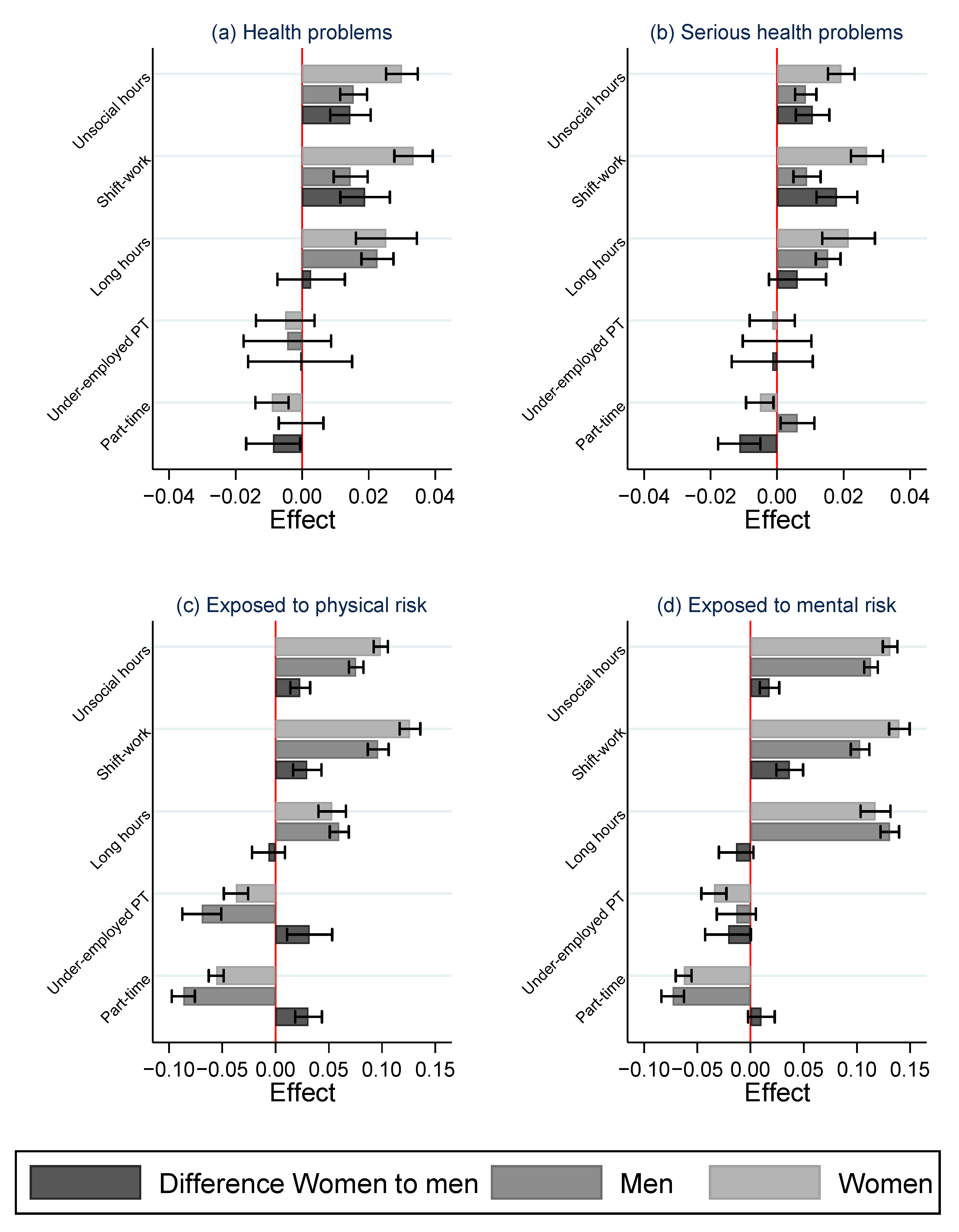

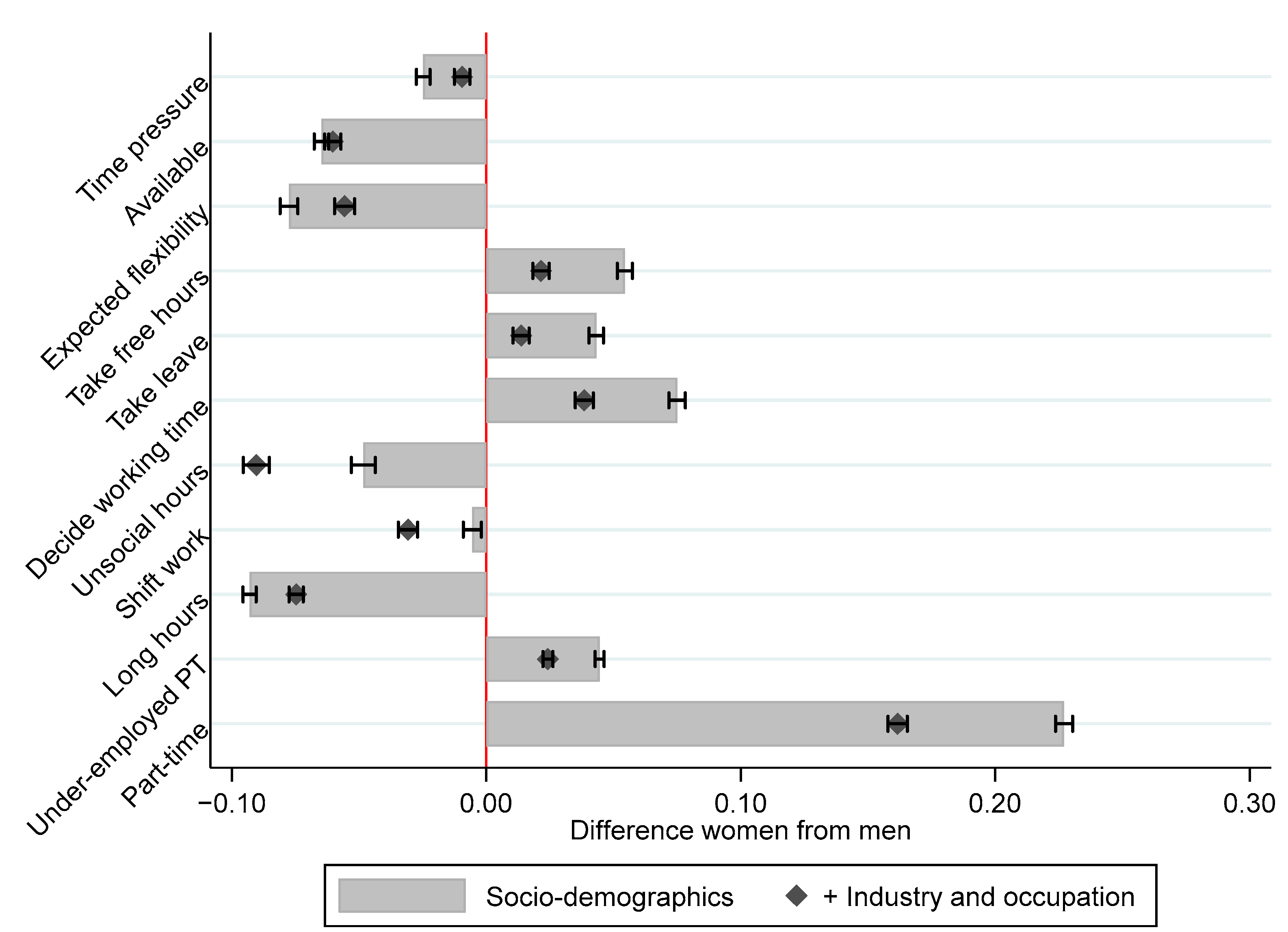

3.1. Study 1: Gender Differences in the Relationship between Temporal Dimensions of Job Quality and Workers’ Health and Well-Being

3.2. Study 2: Supportive Evidence from the Labor Force Survey

4. Discussion

- -

- Further longitudinal and experimental research into the impact of working time on women’s health would be needed to substantiate the causal mechanism behind associations established in our analysis.

- -

- Gender segregation in the labor market is a persistent problem in Europe and warrants the monitoring of sectoral differences in temporal job quality.

- -

- There is a shift to a higher prevalence of remote and hybrid working practices in Europe. In this context, investigations into working time and conditions of home-based workers are highly relevant for research on determinants of health inequalities.

- -

- Life-course perspective should be adopted in the analysis of work-life conflict and its health effects. Gendered division of unpaid work may lead to accumulation of time-based strain from paid and unpaid work for women at particular life stages and increased health risks.

- -

- Precarious employment has been increasing in Europe over the past decades and the trend is expected to continue. This context merits further intersectional analyses on temporal job quality and health.

- -

- The exposure to work-related psychosocial risks should be prevented with gender sensitive occupational safety and health and working time regulations.

- -

- Work-hour mismatch (working more or less hours than desired) is gendered and linked to negative health outcomes. Working time polices should be further developed to address and balance the situation.

- -

- Working time regulation at the European Union level should be further developed to account for the different aspects of temporal job quality. Our study demonstrates that not only excessively long working hours should be addressed in regulation on health and safety grounds, but that other aspects of working time organizations, such as predictability, control, autonomy, and atypical schedules, have important health outcomes.

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eurofound. Working Conditions and Workers’ Health; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2019; Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/publications/report/2019/working-conditions-and-workers-health (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Fujishiro, K.; Ahonen, E.Q.; Winkler, M. Poor-quality employment and health: How a welfare regime typology with a gender lens illuminates a different work-health relationship for men and women. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 291, 114484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos-Serna, J.; Ronda-Pérez, E.; Artazcoz, L.; Moen, B.E.; Benavides, F.G. Gender inequalities in occupational health related to the unequal distribution of working and employment conditions: A systematic review. Int. J. Equity Health 2013, 12, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rafnsdóttir, G.L.; Heijstra, T.M. Balancing work–family life in academia: The power of time. Gend. Work Organ. 2013, 20, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devetter, F.X. Gender differences in time availability: Evidence from France. Gend. Work Organ. 2009, 6, 429–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryson, V. Gender and the Politics of Time. In Feminist Theory and Contemporary Debates; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin, P.; Albani, V.; Bambra, C. Gender Equality and Health in the EU; European Commission, Directorate-General for Justice and Consumers, Publications Office: Brussels, Belgium, 2021; Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2838/956001 (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Piasna, A. ‘Bad Jobs’ Recovery? European Job Quality Index 2005–2015; European Trade Union Institute (ETUI): Brussels, Belgium, 2017; Available online: https://www.etui.org/publications/working-papers/bad-jobs-recovery-european-job-quality-index-2005-2015 (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Artazcoz, L.; Cortès-Franch, I.; Escribà-Agüir, V.; López, M.; Benavides, F.G. Long Working Hours and Job Quality in Europe: Gender and Welfare State Differences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tucker, P.; Folkard, S. Working Time, Health, and Safety: A Research Synthesis Paper; International Labour Organisation (ILO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2012; Available online: https://www.ilo.org/travail/info/publications/WCMS_181673/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Pega, F.; Bálint Náfrádi, N.C.; Momen, Y.U.; Streicher, K.N.; Prüss-Üstün, A.M.; Descatha, A.; Driscoll, T.; Fischer, F.M.; Godderis, L.; Kiiver, H.M.; et al. Global, regional, and national burdens of ischemic heart disease and stroke attributable to exposure to long working hours for 194 countries, 2000–2016: A systematic analysis from the WHO/ILO Joint Estimates of the Work-related Burden of Disease and Injury. Environ. Int. 2021, 154, 106595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivimäki, M.; Virtanen, M.; Nyberg, S.T.; Batty, G.D. The WHO/ILO report on long working hours and ischemic heart disease—Conclusions are not supported by the evidence. Environ. Int. 2020, 144, 106048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, C.R.C.; Marqueze, E.C.; Sargent, C.; Wright, K.P., Jr.; Ferguson, S.A.; Tucker, P. Working Time Society consensus statements: Evidence-based effects of shift work on physical and mental health. Ind. Health 2019, 57, 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brown, J.P.; Martin, D.; Nagaria, Z.; Verceles, A.C.; Jobe, S.L.; Wickwire, E.M. Mental Health Consequences of Shift Work: An Updated Review. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2020, 22, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, A.; Adjei, N.K. Work-life balance and self-reported health among working adults in Europe: A gender and welfare state regime comparative analysis. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisler, S.; Omansky, R.; Alenick, P.R.; Tumminia, A.M.; Eatough, E.M.; Johnson, R.C. Work-life conflict and employee health: A review. J. Appl. Behav. Res. 2018, 23, e12157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hämmig, O.; Bauer, G.F. Work, work–life conflict and health in an industrial work environment. Occup. Med. 2014, 64, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brauchli, R.; Bauer, G.F.; Hämmig, O. Relationship Between Time-Based Work-Life Conflict and Burnout: A Cross-Sectional Study Among Employees in Four Large Swiss Enterprises. Swiss J. Psychol. 2021, 70, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hämmig, O.; Knecht, M.; Läubli, T.; Bauer, G.F. Work-life conflict and musculoskeletal disorders: A cross-sectional study of an unexplored association. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2011, 12, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Henly, J.R.; Lambert, S.J. Unpredictable Work Timing in Retail Jobs: Implications for Employee Work–Life Conflict. ILR Rev. 2014, 67, 986–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eek, F.; Axmon, A. Gender inequality at home is associated with poorer health for women. Scand. J. Public Health 2015, 43, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griep, R.H.; Toivanen, S.; van Diepen, C.; Guimarães, J.M.N.; Camelo, L.V.; Juvanhol, L.L.; Aquino, E.M.; Chor, D. Work–Family Conflict and Self-Rated Health: The Role of Gender and Educational Level. Baseline Data from the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health (ELSA-Brasil). Int. J. Behav. Med. 2016, 23, 372–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hegewald, J.; Starke, K.R.; Garthus-Niegel, S.; Schulz, A.; Nübling, M.; Latza, U.; Jankowiak, S.; Liebers, F.; Rossnagel, K.; Riechmann-Wolf, M.; et al. Work-life conflict and cardiovascular health: 5-year follow-up of the Gutenberg Health Study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0258075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunau, T.; Bambra, C.; Eikemo, T.A.; van der Wel, K.A.; Dragano, N. A balancing act? Work–life balance, health and well-being in European welfare states. Eur. J. Public Health 2014, 24, 422–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moen, P.; Kelly, E.L.; Lam, J. Healthy work revisited: Do changes in time strain predict well-being? J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2013, 18, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- EU-OSHA, ESENER 2019, Third European Survey of Enterprises on New and Emerging. Available online: https://visualisation.osha.europa.eu/esener/#!/en/survey/overview/2019 (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Costa, G.; Sartori, S.; Akerstedt, T. Influence of flexibility and variability of working hours on health and well-being. Chrono. Int. 2006, 23, 1125–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shifrin, N.V.; Michel, J.S. Flexible work arrangements and employee health: A meta-analytic review. Work Stress 2021, 36, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, S.C.; Kecklund, G.; Leineweber, C. The mediating effect of work-life interference on the relationship between work-time control and depressive and musculoskeletal symptoms. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2020, 46, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McNamara, T.M.; Bohle, P.; Quinlan, M. Precarious employment, working hours, work-life conflict and health in hotel work. Appl. Ergon. 2011, 42, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Julià, M.; Vanroelen, C.; Bosmans, K.; Van Aerden, K.; Benach, J. Precarious Employment and Quality of Employment in Relation to Health and Well-being in Europe. Int. J. Health Serv. 2017, 47, 389–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanroelen, C.; Julià, M.; Van Aerden, K. Precarious Employment: An Overlooked Determinant of Workers’ Health and Well-Being? In Flexible Working Practices and Approaches; Korunka, C., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, B.; Hünefeld, L. Temporary Agency Work and Well-Being—The Mediating Role of Job Insecurity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donnelly, R.; Schoenbachler, A. Part-time work and health in the United States: The role of state policies. SSM—Popul. Health 2021, 15, 100891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauhanen, M.; Nätti, J. Involuntary Temporary and Part-Time Work, Job Quality and Well-Being at Work; Working Paper; Labour Institute for Economic Research: Helsinki, Finland. Available online: https://labore.fi/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/sel272.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Angrave, D.; Charlwood, A. What is the relationship between long working hours, over-employment, under-employment and the subjective well-being of workers? Longitudinal evidence from the UK. Hum. Relat. 2015, 68, 1491–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kamerāde, D.; Richardson, H. Gender segregation, underemployment and subjective well-being in the UK labour market. Hum. Relat. 2018, 71, 285–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nielsen, H.B.; Gregersen, L.S.; Bach, E.S.; Dyreborg, J.; Ilsøe, A.; Larsen, T.P.; Pape, K.; Pedersen, J.; Garde, A.H. A comparison of work environment, job insecurity, and health between marginal part-time workers and full-time workers in Denmark using pooled register data. J. Occup. Health 2021, 63, e12251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamerāde, D.; Wang, S.; Burchell, B.; Balderson, S.U.; Coutts, A. A shorter working week for everyone: How much paid work is needed for mental health and well-being? Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 241, 112353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berniell, I.; Bietenbeck, J. The effect of working hours on health. Econ. Hum. Biol. 2020, 39, 100901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Kamerāde, D.; Burchell, B.; Coutts, A.; Balderson, S.U. What matters more for employees’ mental health: Job quality or job quantity? Camb. J. Econ. 2021, 46, beab054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartoll, X.; Cortès, I.; Artazcoz, L. Full-and part-time work: Gender and welfare-type differences in European working conditions, job satisfaction, health status, and psychosocial issues. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2014, 40, 370–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eurofound. Sixth European Working Conditions Survey—Overview Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016; Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/publications/report/2016/working-conditions/sixth-european-working-conditions-survey-overview-report (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Burchell, B.; Sehnbruch, K.; Piasna, A.; Agloni, N. The quality of employment and decent work: Definitions, methodologies, and ongoing debates. Camb. J. Econ. 2014, 38, 459–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Felstead, A.; Gallie, D.; Green, F.; Henske, G. Conceiving, designing and trailing a short-form measure of job quality: A proof-of-concept study. Ind. Relat. J. 2019, 50, 2–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, F.; Mostafa, T. Trends in Job Quality in Europe; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2012; Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/publications/report/2012/working-conditions/trends-in-job-quality-in-europe (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Leschke, J.; Watt, A. Challenges in constructing a multi-dimensional European job quality index. Soc. Indic. Res. 2014, 118, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, H.; Strazdins, L.; Welsh, J. Hour-glass ceilings: Work-hour thresholds, gendered health inequities. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 176, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, M.; Ferrie, J.E.; Singh-Manoux, A.; Shipley, M.J.; Stansfeld, S.A.; Marmot, M.G.; Ahola, K.; Vahtera, J.; Kivimäki, M. Long working hours and symptoms of anxiety and depression: A 5-year follow-up of the Whitehall II study. Psychol. Med. 2011, 41, 2485–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ryu, J.; Yoon, Y.; Kim, H.; Kang, C.W.; Jung-Choi, K. The Change of Self-Rated Health According to Working Hours for Two Years by Gender. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jeon, J.; Lee, W.; Choi, W.J.; Ham, S.; Kang, S.K. Association between Working Hours and Self-Rated Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shin, M.G.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, T.K.; Kang, D. Effects of Long Working Hours and Night Work on Subjective Well-Being Depending on Work Creativity and Task Variety, and Occupation: The Role of Working-Time Mismatch, Variability, Shift Work, and Autonomy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Occupational Health: Stress at the Workplace. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/ccupational-health-stress-at-the-workplace (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Daryl, B.; O’Connor, J.F.; Thayer, K.V. Stress and Health: A Review of Psychobiological Processes. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2021, 72, 663–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedhammer, I.; Sultan-Taïeb, H.; Parent-Thirion, A.; Chastang, J.-F. Update of the fractions of cardiovascular diseases and mental disorders attributable to psychosocial work factors in Europe. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2021, 95, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, P.; Gkiouleka, A. A Scoping Review of Psychosocial Risks to Health Workers during the Covid-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Aerden, K.; Puig-Barrachina, V.; Bosmans, K.; Vanroelen, C. How does employment quality relate to health and job satisfaction in Europe? A typological approach. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 158, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bambra, C.; Albani, V.; Franklin, P. COVID-19 and the gender health paradox. Scand. J. Public Health 2021, 49, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgmann, L.-S.; Rattay, P.; Lampert, T. Health-Related Consequences of Work-Family Conflict from a European Perspective: Results of a Scoping Review. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dixon, J.; Banwell, C.; Strazdins, L.; Corr, L.; Burgess, J. Flexible employment policies, temporal control and health promoting practices: A qualitative study in two Australian worksites. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0224542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurofound 2020. Living, Working and COVID-19, COVID-19 Series; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Eurofound 2021. Living, Working and COVID-19 (Update April 2021): Mental Health and Trust Decline Across EU as Pandemic Enters Another Year; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE). Gender Equality Index 2021 Report: Health. Unpaid Care Workloads and Social Isolation Affect Well-Being. Available online: https://eige.europa.eu/publications/gender-equality-index-2021-report/unpaid-care-workloads-and-social-isolation-affect-well-being (accessed on 29 March 2022).

- Kurowska, A. Gendered Effects of Home-Based Work on Parents’ Capability to Balance Work with Non-work: Two Countries with Different Models of Division of Labour Compared. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 151, 405–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hjálmsdóttir, A.; Bjarnadóttir, V.S. “I have turned into a foreman here at home”: Families and work–life balance in times of COVID-19 in a gender equality paradise. Gender Work Organ. 2020, 28, 268–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandola, T.; Booker, C.L.; Kumari, M.; Benzeval, M. Are Flexible Work Arrangements Associated with Lower Levels of Chronic Stress-Related Biomarkers? A Study of 6025 Employees in the UK Household Longitudinal Study. Sociology 2019, 53, 779–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Artazcoz, L. Gender inequalities in working time and health in Europe. In Gender, Working Conditions and Health. What Has Changed? Casse, C., De Troyer, M., Eds.; European Trade Union Institute (ETUI): Brussels, Belgium, 2021; Available online: https://www.etui.org/publications/gender-working-conditions-and-health (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- World Health Organization. Women’s Health and Well-Being in EUROPE: Beyond the Mortality Advantage; World Health Organization: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/332324/9789289051910-eng.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- European Parliament, Directorate General for Internal Policies, Policy Department a Economic and Scientific Policy. Precarious Employment in Europe: Patterns, Trends and Policy Strategies. Report. 2016. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2016/587285/IPOL_STU(2016)587285_EN.pdf (accessed on 29 March 2022).

- International Labour Organisation (ILO). From precarious work to decent work. In Outcome Document to the Workers’ Isymposium on Policies and Regulations to Combat Precarious Employment; International Labour Office, Bureau for Workers’ Activities: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Canivet, C.; Bodin, T.; Emmelin, M.; Toivanen, S.; Moghaddassi, M.; Östergren, P.-O. Precarious employment is a risk factor for poor mental health in young individuals in Sweden: A cohort study with multiple follow-ups. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Benach, J.; Vives, A.; Tarafa, G.; Delclos, C.; Muntaner, C. What should we know about precarious employment and health in 2025? Framing the agenda for the next decade of research. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2016, 45, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gray, B.; Grey, C.; Hookway, A.; Homolova, L.; Davies, A. Differences in the impact of precarious employment on health across population subgroups: A scoping review. Perspect. Public Health 2021, 141, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, C.L.; Toch-Marquardt, M.; Albani, V.; Eikemo, T.A.; Bambra, C. The contribution of employment and working conditions to occupational inequalities in non-communicable diseases in Europe. Eur. J. Public Health 2021, 31, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunn, V.; Håkansta, C.; Vignola, E.; Matilla-Santander, N.; Kreshpaj, B.; Wegman, D.H.; Hogstedt, C.; Ahonen, E.Q.; Muntaner, C.; Baron, S.; et al. Initiatives addressing precarious employment and its effects on workers’ health and well-being: A protocol for a systematic review. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez Rivero, F.; Padrosa, E.; Utzet, M.; Benach, J.; Julià, M. Precarious employment, psychosocial risk factors and poor mental health: A cross-sectional mediation analysis. Saf. Sci. 2021, 143, 105439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuter, M.; Wahrendorf, M.; Di Tecco, C.; Probst, T.M.; Chirumbolo, A.; Ritz-Timme, S.; Barbaranelli, C.; Iavicoli, S.; Dragano, N. Precarious employment and self-reported experiences of unwanted sexual attention and sexual harassment at work. An analysis of the European Working Conditions Survey. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0233683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiadou, A.; Antonacopoulou, E. Leading Through Social Distancing: The Future of Work, Corporations and Leadership from Home. Gend. Work Organ. 2021, 28, 749–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament. DRAFT REPORT on Women’s Poverty in EUROPE. 2021. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/FEMM-PR-699337_EN.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Smith, M.; Piasna, A.; Burchell, B.; Rubery, J.; Rafferty, A.; Rose, J.; Carter, L. Women, Men and Working Conditions in Europe; Eurofound: Dublin, Ireland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Eurofound. Women and Labour Market Equality: Has COVID-19 Rolled Back Recent Gains? Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020; Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/publications/policy-brief/2020/women-and-labour-market-equality-has-covid-19-rolled-back-recent-gains (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Nivakoski, S.; Mascherini, M. Gender Differences in the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Employment, Unpaid Work and Well-Being in the EU. Intereconomics 2021, 56, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oakman, J.; Kinsman, N.; Stuckey, R.; Graham, M.; Weale, V. A rapid review of mental and physical health effects of working at home: How do we optimise health? BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Río-Lozano, M.; García-Calvente, M.; Elizalde-Sagardia, B.; Maroto-Navarro, G. Caregiving and Caregiver Health 1 Year into the COVID-19 Pandemic (CUIDAR-SE Study): A Gender Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mensah, A. Job Stress and Mental Well-Being among Working Men and Women in Europe: The Mediating Role of Social Support. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Dimension of Temporal Job Quality | Items from the EWCS Used to Construct the Index | Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| JQ1 Unsocial hours | Work at night; work on Sundays; work on Saturdays; shift work *. | All Women Men | 82.6 (20.2) 84.0 (19.6) 81.3 (20.7) |

| JQ2 Long hours | Work more than 48 h per week; work long days of more than 10 h; no recovery period (less than 11 h between two working days). | All Women Men | 83.3 (26.0) 88.4 (21.6) 78.6 (28.8) |

| JQ3 Flexibility and control | Changes in work schedules **; short-term flexibility (taking an hour or two off for personal reasons); requested to come into work at short notice. | All Women Men | 63.5 (20.0) 62.5 (19.6) 64.4 (20.2) |

| JQ4 Time pressure | Working to tight deadlines; factors constraining pace of work: colleagues, customer demands, production/performance targets, machine speed, boss; not having enough time to get the job done; working during free time to meet work demands. | All Women Men | 67.4 (18.1) 69.1 (18.1) 65.8 (17.9) |

| JQ Full index | Overall temporal job quality: scale based on all items used in the construction of JQ1—JQ4. | All Women Men | 67.7 (13.3) 69.8 (12.4) 65.8 (13.8) |

| Name of Measure | Construction of the Measure Based on the EWCS | Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Negative impact of work on health | Subjective assessment of the impact of work on health: (1) affects mainly negatively, (0) affects mainly positively or does not affect. | All Women Men | 0.25 (0.43) 0.23 (0.42) 0.27 (0.44) |

| Health problems in the past 12 months | Reported health problems experienced in the 12 months prior to the survey (min. 0, max. 10) *. | All Women Men | 2.27 (2.06) 2.42 (2.09) 2.12 (2.03) |

| Sustainable work | Perceived ability to work in the current job or a similar one until the age of 60: (1) yes, (0) no. | All Women Men | 0.72 (0.45) 0.70 (0.46) 0.74 (0.44) |

| Subjective well-being | Measured by the World Health Organization’s Well-Being Index (WHO-5) (min. 0, max. 5) | All Women Men | 3.41 (1.00) 3.35 (1.02) 3.46 (0.97) |

| Name of Measure | Description | Availability | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health problems | Person suffered any physical or mental health problems that were caused or made worse by work, apart from accidents. | 2020 AHM | 0.10 (0.31) |

| Serious health problems | Person experienced a health problem at work (as defined in Health problems) that limits the ability to carry out day to day activities either at work or outside work to some extent or considerably | 2020 AHM | 0.07 (0.26) |

| Exposed to physical health risk factors | Person is exposed at work to one of eleven risk factors that can affect physical health | 2020 AHM | 0.63 (0.48) |

| Exposed to mental well-being risk factors | Person is exposed at work to one of eight risk factors that can affect mental well-being. | 2020 AHM | 0.45 (0.50) |

| Part-time | Person works part-time rather than full-time | 2000–2020 | 0.18 (0.39) |

| Long hours | Indicator: Person usually works more than 48 h per week. | 2000–2020 | 0.09 (0.28) |

| Under-employed part-time | Person works part-time since they could not find a full-time job | 2000–2020 | 0.04 (0.21) |

| Unsocial hours | Person usually works either evenings, nights, Saturdays, or Sundays | 2000–2020 | 0.42 (0.49) |

| Shift work | Person works in shifts. | 2000–2020 | 0.18 (0.38) |

| Free to take leave | Possibility to take one or two days of leave within three working days in the main job: 1 (very easy) to 4 (very difficult) | 2019 AHM | 0.47 (0.33) |

| Free to take hours off | Possibility to take one or two hours off in the main job for personal or family matters within one working day: from 1 (very easy) to 4 (very difficult) | 2019 AHM | 0.37 (0.34) |

| Decide working time | Who decides on working time: (1) worker fully decides; (2) worker with certain restrictions; (3) employer or organization | 2019 AHM | 1.58 (0.78) |

| Expected flexibility | Frequency to which the worker has to face unforeseen demands for changed working time in the main job: (1) less than every month or never; (2) less than every week but at least every month; (3) at least once a week | 2019 AHM | 1.62 (0.82) |

| Available | Worker was contacted during leisure time in the last two months to take action before the next working day for the main job: (1) not contacted in the last 2 months; (2) contacted on a few occasions; (3) contacted several times and not expected to act before the next working day; (4) contacted several times and expected to act before the next working day | 2019 AHM | 1.72 (1.01) |

| Time pressure | Frequency to which the person works under time pressure in the main job: (1) never, (2) sometimes, (3) often, (4) always | 2019 AHM | 2.31 (0.95) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Franklin, P.; Zwysen, W.; Piasna, A. Temporal Dimensions of Job Quality and Gender: Exploring Differences in the Associations of Working Time and Health between Women and Men. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4456. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084456

Franklin P, Zwysen W, Piasna A. Temporal Dimensions of Job Quality and Gender: Exploring Differences in the Associations of Working Time and Health between Women and Men. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(8):4456. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084456

Chicago/Turabian StyleFranklin, Paula, Wouter Zwysen, and Agnieszka Piasna. 2022. "Temporal Dimensions of Job Quality and Gender: Exploring Differences in the Associations of Working Time and Health between Women and Men" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 8: 4456. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084456

APA StyleFranklin, P., Zwysen, W., & Piasna, A. (2022). Temporal Dimensions of Job Quality and Gender: Exploring Differences in the Associations of Working Time and Health between Women and Men. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(8), 4456. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084456