Effect of the Promulgation of the New Migrant’s Employment Law on Migrant Insurance Coverage in Thailand: An Interrupted Time Series Analysis, 2016–2018

Abstract

:1. Background

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Data Sources

2.3. Analysis

2.4. Ethics Consideration

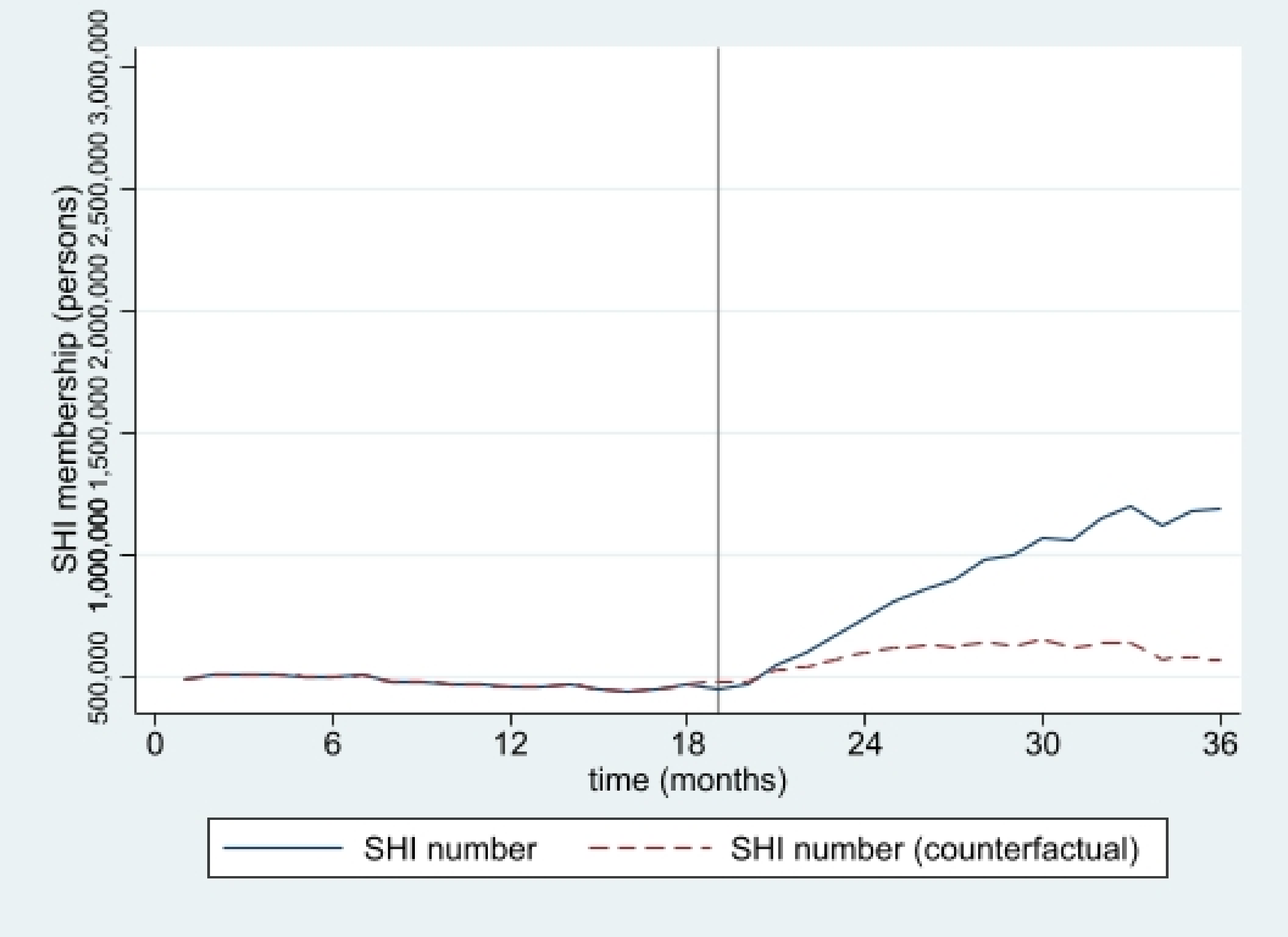

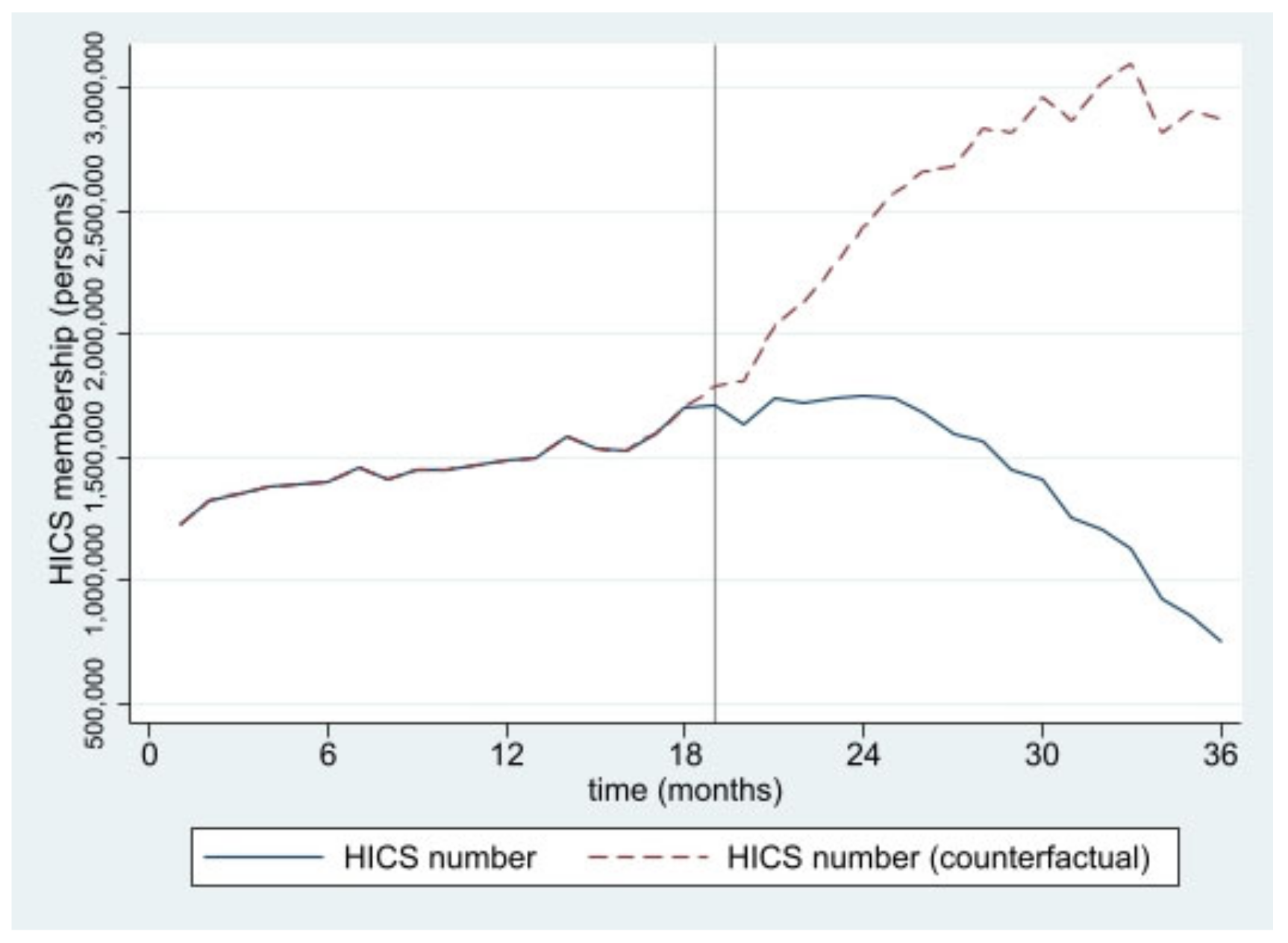

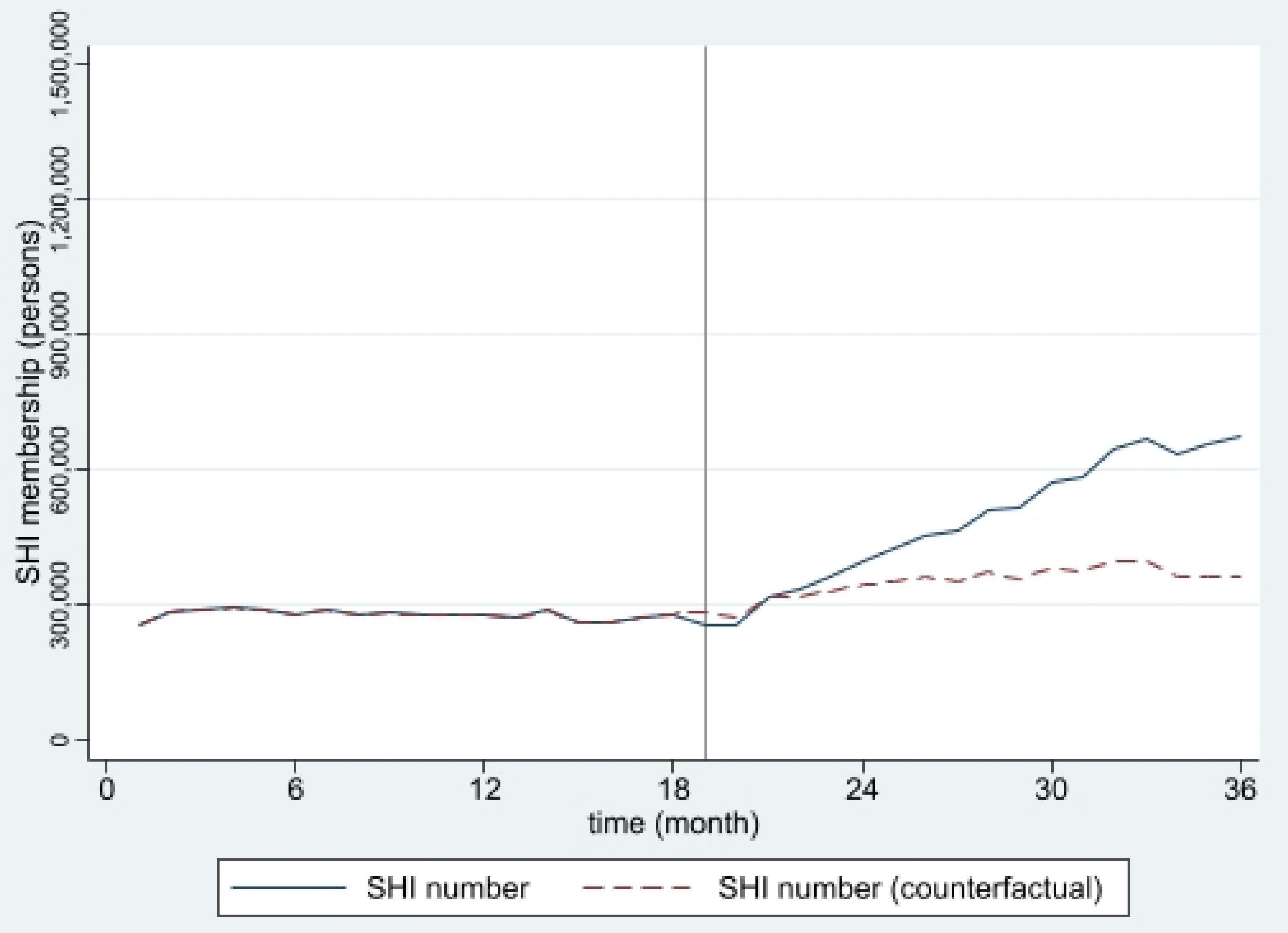

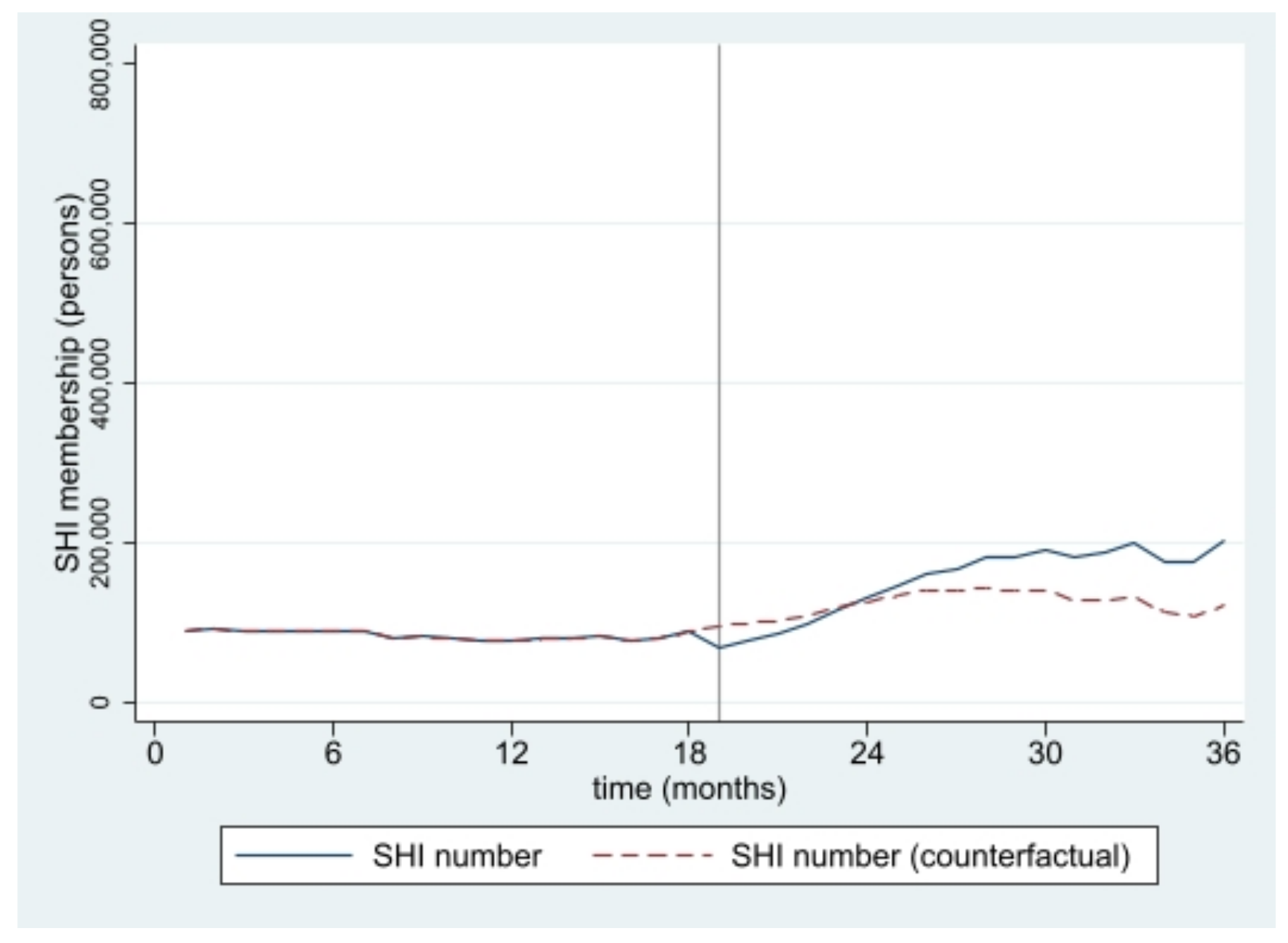

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zimmerman, C.; Kiss, L.; Hossain, M. Migration and Health: A Framework for 21st Century Policy-Making. PLoS Med. 2011, 8, e1001034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Borjas, G.J. Economic theory and international migration. Int. Migr. Rev. 1989, 23, 457–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Tracking Universal Health Coverage: 2017 Global Monitoring Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Legido-Quigley, H.; Pocock, N.; Tan, S.T.; Pajin, L.; Suphanchaimat, R.; Wickramage, K.; McKee, M.; Pottie, K. Migration and Health: Healthcare is not universal if undocumented migrants are excluded. BMJ 2019, 366, l4160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thailand Board of Investment Thailand Social and Culture. Thailand in Brief—Social and Culture; Thailand Board of Investment: Bangkok, Thailand, 2022; Available online: https://www.boi.go.th/index.php?page=social_and_culture (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- Aoki, M. Chapter 7 Thailand’s Migrant Worker Management Policy as Regional Development Strategy. In Rethinking Migration Governance in the Mekong Region: From the Perspective of the Migrant Workers and Their Employers; ERIA Research Project Report FY2017 No. 19; Hatsukano, N., Ed.; ERIA and IDE-JETRO: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2019; pp. 175–199. Available online: https://www.ide.go.jp/library/English/Publish/Reports/Ec/pdf/201902_02_ch07.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2021).

- Chalamwong, Y. Management of Cross-border Low-Skilled Workers in Thailand: An Update. TDRI Q. Rev. 2012, 12, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Medina, A.F. Minimum Wages in ASEAN for 2021; ASEAN Briefing: Hong Kong, China, 2021; Available online: https://www.aseanbriefing.com/news/minimum-wages-in-asean-for-2021/ (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- Foreign Workers Administration Office. The Situation of Migrant Workers in December 2018; Foreign Workers Administration Office: Bangkok, Thailand, 2019.

- Suphanchaimat, R.; Kosiyaporn, H.; Limwattanayingyong, A. Migrant Policies in Thailand in Light of the Universal Health Coverage: Evolution and Remaining Challenges. Outbreak Surveill. Investig. Response J. 2019, 12, 68–74. [Google Scholar]

- Srithamrongsawat, S.; Wisessang, R.; Ratjaroenkhajorn, S. Financing Healthcare for Migrants: A Case Study from Thailand; International Organization for Migration: Bangkok, Thailand, 2009; Available online: https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/financing_healthcare_for_migrants_thailand.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- The Government Public Relations Department Medical Check-ups and Health Insurance for Migrant Workers. 2016. Available online: https://thailand.prd.go.th/ewt_news.php?nid=3051&filename=index (accessed on 17 November 2021).

- Suphanchaimat, R.; Putthasri, W.; Prakongsai, P.; Tangcharoensathien, V. Evolution and complexity of government policies to protect the health of undocumented/illegal migrants in Thailand—The unsolved challenges. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2017, 10, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tangcharoensathien, V.; Witthayapipopsakul, W.; Panichkriangkrai, W.; Patcharanarumol, W.; Mills, A. Health systems development in Thailand: A solid platform for successful implementation of universal health coverage. Lancet 2018, 391, 1205–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Public Health. Ministry of Public Health Announcement: Health Check and Health Insurance for Migrant Workers B.E.2562; Ministry of Public Health: Nonthaburi, Thailand, 2019. Available online: https://dhes.moph.go.th/?p=4869 (accessed on 1 April 2022). (In Thai)

- Thongmak, B.; Mitthong, W. Perception of Benefits from Health Insurance Card and Social Security Card among Migrant Workers and Hospital Personnel at Samut Sakhon Province. Public Health J. Burapha Univ. 2021, 16, 52–64. [Google Scholar]

- Panjaphothiwat, N.; Pairam, U.; Jackraphanich, N.; Manohan, P. The study of problems and obstacles in accessing to health services of migrant workers in the Special Economic Zones Chiang Rai Province, Mae Sai, Chiang Saen and Chiang Khong District. J. Nurs. Sci. Health 2021, 44, 88–99. [Google Scholar]

- Suphanchaimat, R. “Health Insurance Card Scheme” for Cross-Border Migrants in Thailand: Responses in Policy Implementation & Outcome Evaluation; London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Decharatanachart, W.; Un-Ob, P.; Putthasri, W.; Prapasuchat, N. The health insurance model for migrant workers’ dependents: A case study of Samut Sakhon Province, Thailand. Kasetsart J. Soc. Sci. 2021, 42, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Royal Thai Government Gazette. Foreigners’ Working Management Emergency Decree, B.E.2560 (2017); The Office of The Council of State: Bangkok, Thailand, 2017. Available online: https://www.doe.go.th/prd/assets/upload/files/legal_th/99cafe53a0d300f8fdb877b08ec99bd6.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Lopez Bernal, J.; Soumerai, S.; Gasparrini, A. A methodological framework for model selection in interrupted time series studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2018, 103, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lagarde, M. How to do (or not to do)… Assessing the impact of a policy change with routine longitudinal data. Health Policy Plan. 2012, 27, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wagner, A.K.; Soumerai, S.B.; Zhang, F.; Ross-Degnan, D. Segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series studies in medication use research. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2002, 27, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foreign Workers Administration Office. Monthly Statistics of Work Permit Holding Migrants. Available online: https://www.doe.go.th/prd/alien/statistic/param/site/152/cat/82/sub/0/pull/category/view/list-label (accessed on 1 September 2021). (In Thai)

- Suphanchaimat, R.; Pudpong, N.; Prakongsai, P.; Putthasri, W.; Hanefeld, J.; Mills, A. The Devil Is in the Detail-Understanding Divergence between Intention and Implementation of Health Policy for Undocumented Migrants in Thailand. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Srisai, P.; Phaiyarom, M.; Suphanchaimat, R. Perspectives of Migrants and Employers on the National Insurance Policy (Health Insurance Card Scheme) for Migrants: A Case Study in Ranong, Thailand. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2020, 13, 2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pudpong, N.; Durier, N.; Julchoo, S.; Sainam, P.; Kuttiparambil, B.; Suphanchaimat, R. Assessment of a Voluntary Non-Profit Health Insurance Scheme for Migrants along the Thai–Myanmar Border: A Case Study of the Migrant Fund in Thailand. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cretti, G. Human Trafficking in the Thai Fishing Industry: A Call to Action for EU and US Importers. IAI Comment 2020, 20, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Asian Research Center for Migration, Centre for European Studies. The Report of Policy Development on the Problems of Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing, Forced Labour and Human Trafficking in Sea Fisheries in 2016; Centre for European Studies (CES): Bangkok, Thailand, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Thailand’s Rapid Fisheries Reform Results in a Green Card from the EU—Seafood Task ForceSeafood Task Force. Available online: https://www.seafoodtaskforce.global/thailands-rapid-fisheries-reform-results-in-a-green-card-from-the-eu/ (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Kadfak, A.; Linke, S. More than just a carding system: Labour implications of the EU’s illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing policy in Thailand. Mar. Policy 2021, 127, 104445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). The ASEAN Consensus on the Protection and Promotion of the Rights of Migrant Workers; ASEAN Member State: Manila, The Philippines, 2017; Available online: https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/ASEAN-Consensus-on-the-Protection-and-Promotion-of-the-Rights-of-Migrant-Workers1.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Herberholz, C. The role of external actors in shaping migrant health insurance in Thailand. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0234642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldbaum, H.; Lee, K.; Michaud, J. Global health and foreign policy. Epidemiol. Rev. 2010, 32, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Migrant Workers and Thailand’s Health Security System. Thai Health 2013: Thailand Reform: Restructuring Power, Empowering Citizens; Kanchanachitra, C., Ed.; Institute for Population and Social Research, Mahidol University: Nakhon Pathom, Thailand, 2013; ISBN 978-616-279-427-8. [Google Scholar]

- Kazungu, J.S.; Barasa, E.W. Examining levels, distribution and correlates of health insurance coverage in Kenya. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2017, 22, 1175–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.; Yang, W. Who will drop out of voluntary social health insurance? Evidence from the New Cooperative Medical Scheme in China. Health Policy Plan. 2021, 36, 1013–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, L.; Yip, W.; Hsiao, W. Adverse selection in a voluntary Rural Mutual Health Care health insurance scheme in China. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 63, 1236–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendelsohn, J.B.; Schilperoord, M.; Spiegel, P.; Balasundaram, S.; Radhakrishnan, A.; Lee, C.K.C.; Larke, N.; Grant, A.D.; Sondorp, E.; Ross, D.A. Is forced migration a barrier to treatment success? Similar HIV treatment outcomes among refugees and a surrounding host community in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. AIDS Behav. 2014, 18, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Takla, A.; Barth, A.; Siedler, A.; Stöcker, P.; Wichmann, O.; Deleré, Y. Measles outbreak in an asylum-seekers’ shelter in Germany: Comparison of the implemented with a hypothetical containment strategy. Epidemiol. Infect. 2012, 140, 1589–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozorgmehr, K.; Razum, O. Effect of Restricting Access to Health Care on Health Expenditures among Asylum-Seekers and Refugees: A Quasi-Experimental Study in Germany, 1994–2013. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0131483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trummer, U.; Novak-Zezula, S.; Renner, A.-T.; Wilczewska, I. Cost Analysis of Health Care Provision for Irregular Migrants and EU Citizens without Insurance; International Organization for Migration: Vienna, Austria, 2016; Available online: https://migrationhealthresearch.iom.int/thematic-study-cost-analysis-health-care-provision-irregular-migrants-and-eu-citizens-without (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- Banzon, E.P. Rising Migration Demands ‘Roaming’ Health Coverage. BRINK Conversations and Insights from the Edge of Global Business. 2017. Available online: https://www.brinknews.com/rising-migration-demands-roaming-health-coverage/ (accessed on 17 March 2022).

- Guinto, R.L.L.R.; Curran, U.Z.; Suphanchaimat, R.; Pocock, N.S. Universal health coverage in “One ASEAN”: Are migrants included? Glob. Health Action 2015, 8, 25749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Years | Social Health Insurance (SHI)—n | Health Insurance Card Scheme (HICS)—n | Work Permit Holders—n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All provinces | ||||

| 2016 | Mean (sd) | 488,305 (24,386) | 1,443,654 (199,518) | 1,514,443 (36,762) |

| Median (min–max) | 492,963 (424,622–514,471) | 1,510,908 (1,141,715–1,683,121) | 1,519,111 (1,451,717–1,564,106) | |

| 2017 | Mean (sd) | 528,816 (49,458) | 1,614,758 (177,228) | 1,652,313 (210,673) |

| Median (min–max) | 502,504 (485,864–633,513) | 1,502,834 (1,467,533–1,877,236) | 1,585,838 (1,437,716–2,062,807) | |

| 2018 | Mean (sd) | 1,027,702 (233,819) | 1,290,153 (480,744) | 2,227,335 (84,008) |

| Median (min–max) | 1,162,366 (651,834–1,216,231) | 1,153,788 (822,781–2,121,411) | 2,214,999 (2,119,413–2,356,454) | |

| Greater Bangkok | ||||

| 2016 | Mean (sd) | 275,410 (15,844) | 543,256 (117,572) | 769,309 (34,164) |

| Median (min–max) | 277,737 (231,958–290,615) | 592,282 (377,083–659,449) | 780,842 (666,687–793,718) | |

| 2017 | Mean (sd) | 301,657 (30,223) | 640,520 (54,094) | 877,587 (109,296) |

| Median (min–max) | 287,023 (263,577–363,555) | 615,404 (580,743–726,280) | 834,747 (763,379–1,079,125) | |

| 2018 | Mean (sd) | 565,357 (121,561) | 362,223 (241,832) | 1,230,196 (76,507) |

| Median (min–max) | 622,012 (370,924–677,954) | 279,344 (155,357–772,912) | 1,250,200 (1,113,123–1,356,655) | |

| Border provinces | ||||

| 2016 | Mean (sd) | 86,489 (10,818) | 379,672 (43,726) | 347,666 (37,252) |

| Median (min–max) | 90,144 (53,131–92,248) | 378,498 (325,252–450,625) | 363,108 (294,262–389,708) | |

| 2017 | Mean (sd) | 88,461 (12,113) | 439,736 (76,892) | 334,093 (46,808) |

| Median (min–max) | 86,004 (61,428–108,348) | 396,432 (368,933–552,549) | 325,852 (277,255–423,766) | |

| 2018 | Mean (sd) | 175,561 (37,370) | 465,369 (93,745) | 412,794 (47,121) |

| Median (min–max) | 194,803 (114,406–207,922) | 436,162 (368,504–636,288) | 423,846 (328,286–464,177) | |

| All Provinces | Bangkok and Vicinity | Border Provinces | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (95% CI) | p-Value | Coefficient (95% CI) | p-Value | Coefficient (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| Social Health Insurance (SHI) | ||||||

| Constant | 33.92 (26.83, 41.01) | <0.001 | 38.36 (33.30, 43.42) | <0.001 | 22.86 (15.58, 30.15) | <0.001 |

| Time | −0.20 (−0.80, 0.41) | 0.511 | −0.27 (−0.72, 0.19) | 0.239 | 0.29 (0.35, 0.94) | 0.361 |

| Intervention | −4.16 (−10.63, 2.30) | 0.199 | −5.03 (−11.19, 1.12) | 0.105 | −9.75 (−18.02, −1.48) | 0.022 |

| Postslope | 1.86 (0.88, 2.83) | 0.001 | 1.67 (0.99, 2.35) | <0.001 | 1.77 (0.78, 2.76) | 0.001 |

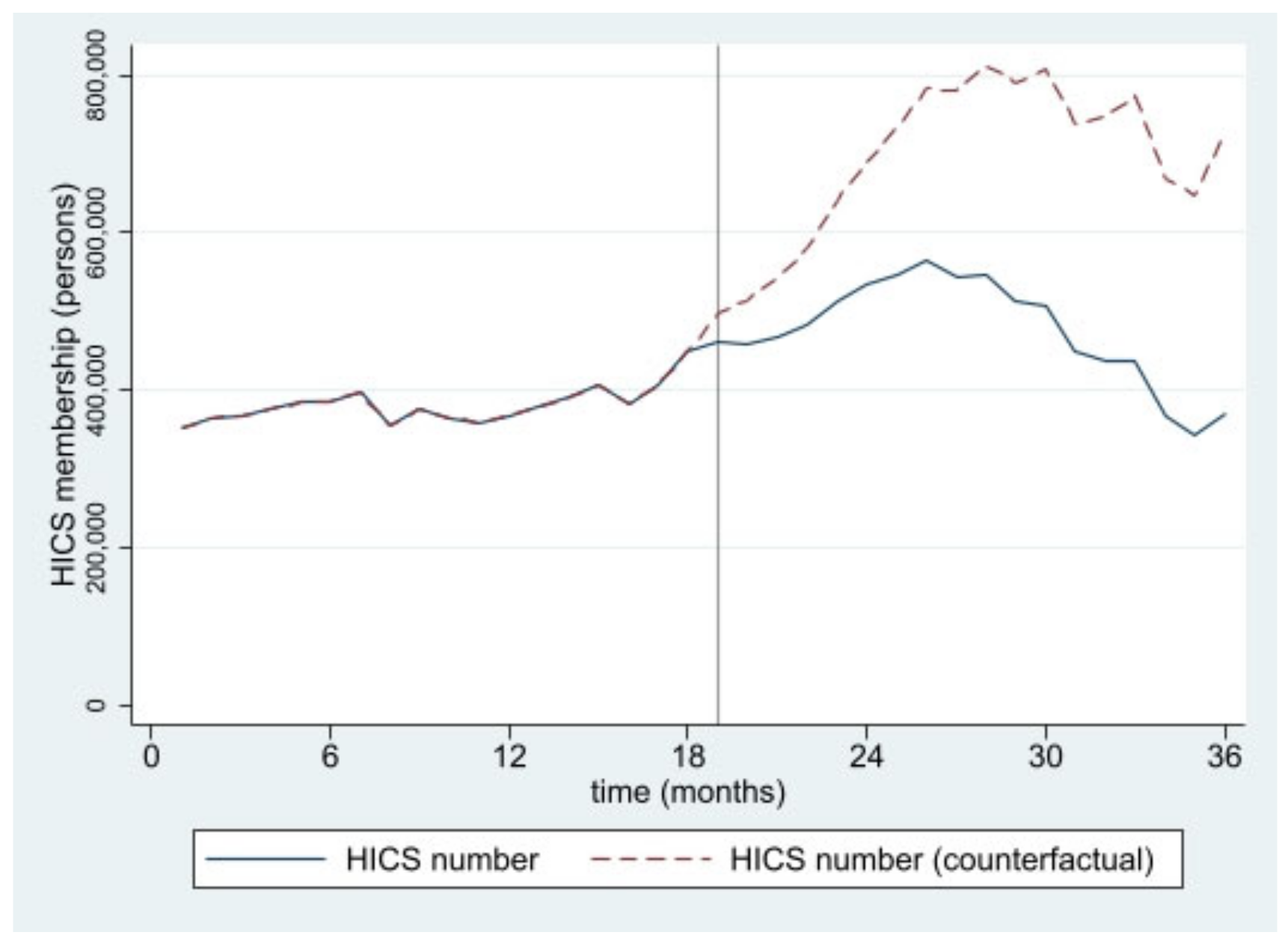

| Health Insurance Card Scheme (HICS) | ||||||

| Constant | 82.93 (66.38, 99.48) | <0.001 | 58.73 (42.10, 75.37) | <0.001 | 87.34 (68.38, 106.30) | <0.001 |

| Time | 1.47 (0.03, 2.90) | 0.045 | 1.40 (−0.02, 2.83) | 0.053 | 3.14 (1.46, 4.82) | 0.001 |

| Intervention | 0.48 (−16.31, 17.27) | 0.954 | 0.77 (−14.90, 16.44) | 0.921 | −6.10 (−27.59, 15.39) | 0.567 |

| Postslope | −5.59 (−7.87, −3.32) | <0.001 | −5.68 (−7.97, −3.38) | <0.001 | −5.11 (−7.69, −2.53) | <0.001 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Witthayapipopsakul, W.; Kosiyaporn, H.; Uansri, S.; Suphanchaimat, R. Effect of the Promulgation of the New Migrant’s Employment Law on Migrant Insurance Coverage in Thailand: An Interrupted Time Series Analysis, 2016–2018. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4384. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074384

Witthayapipopsakul W, Kosiyaporn H, Uansri S, Suphanchaimat R. Effect of the Promulgation of the New Migrant’s Employment Law on Migrant Insurance Coverage in Thailand: An Interrupted Time Series Analysis, 2016–2018. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(7):4384. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074384

Chicago/Turabian StyleWitthayapipopsakul, Woranan, Hathairat Kosiyaporn, Sonvanee Uansri, and Rapeepong Suphanchaimat. 2022. "Effect of the Promulgation of the New Migrant’s Employment Law on Migrant Insurance Coverage in Thailand: An Interrupted Time Series Analysis, 2016–2018" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 7: 4384. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074384

APA StyleWitthayapipopsakul, W., Kosiyaporn, H., Uansri, S., & Suphanchaimat, R. (2022). Effect of the Promulgation of the New Migrant’s Employment Law on Migrant Insurance Coverage in Thailand: An Interrupted Time Series Analysis, 2016–2018. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(7), 4384. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074384