Association of Paternity Leave with Impaired Father–Infant Bonding: Findings from a Nationwide Online Survey in Japan

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

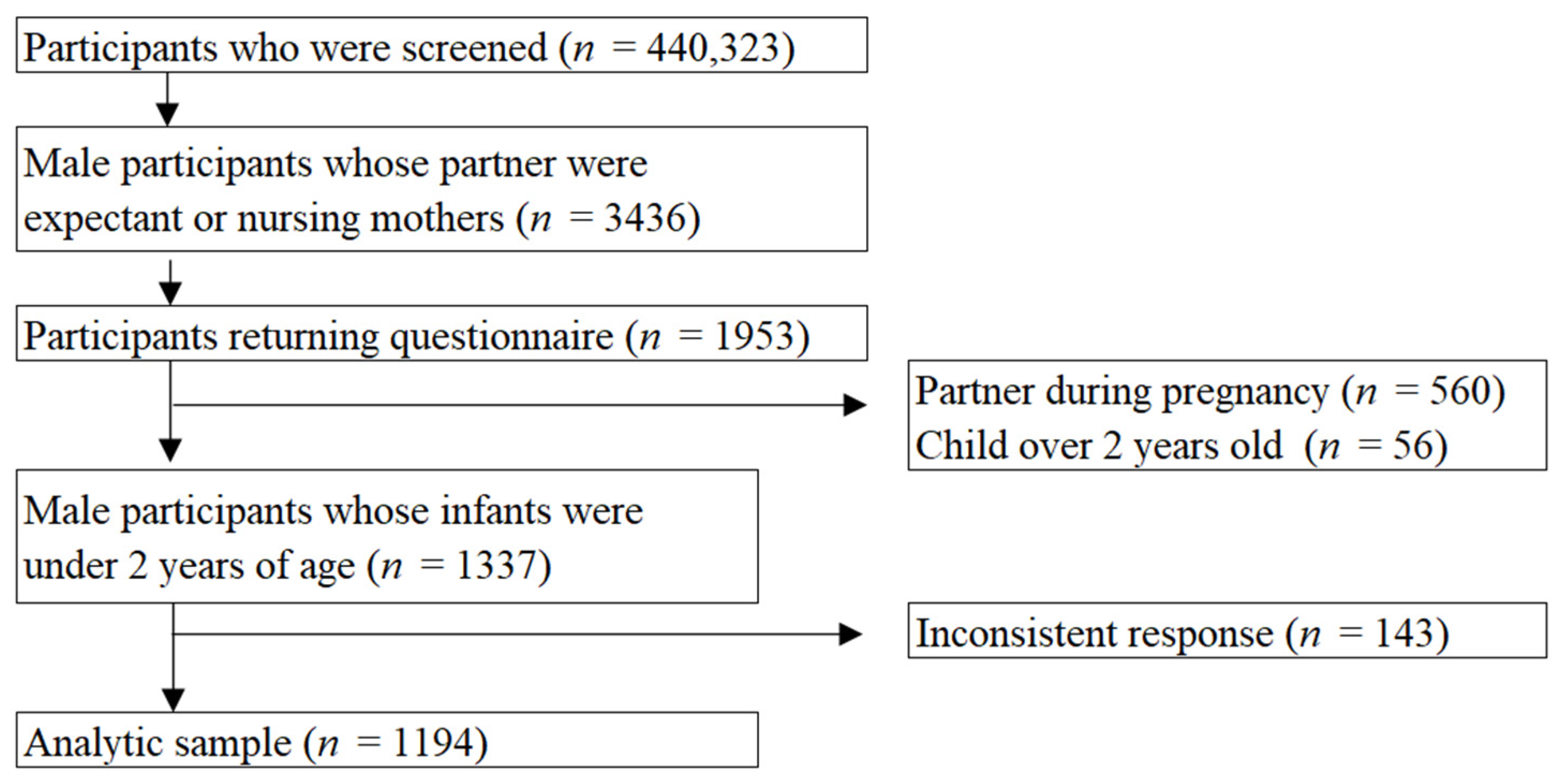

2.1. Study Design and Sample

2.2. Variable Measurement

2.2.1. Father–Infant Bonding

2.2.2. Paternity Leave

2.2.3. Covariates

2.3. Statistical Analyses

2.4. Ethics Approval and Consent to Participants

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kinsey, C.B.; Hupcey, J.E. State of the science of maternal-infant bonding: A principle-based concept analysis. Midwifery 2013, 29, 1314–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Condon, J.T. The assessment of antenatal emotional attachment: Development of a questionnaire instrument. Br. J. Med. Psychol. 1993, 66 Pt 2, 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scism, A.R.; Cobb, R.L. Integrative Review of Factors and Interventions That Influence Early Father-Infant Bonding. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2017, 46, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronte-Tinkew, J.; Carrano, J.; Horowitz, A.; Kinukawa, A. Involvement among resident fathers and links to infant cognitive outcomes. J. Fam. Issues 2008, 29, 1211–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfield, C.F.; Isacco, A. Fathers and the well-child visit. Pediatrics 2006, 117, e637–e645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Howard, K.S.; Lefever, J.E.B.; Borkowski, J.G.; Whitman, T.L. Fathers’ influence in the lives of children with adolescent mothers. J. Fam. Psychol. 2006, 20, 468–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Knoester, C.; Petts, R.J.; Pragg, B. Paternity Leave-Taking and Father Involvement among Socioeconomically Disadvantaged U.S. Fathers. Sex Roles 2019, 81, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mun, E.; Brinton, M.C. Workplace matters: The use of parental leave policy in Japan. Work. Occup. 2015, 42, 335–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Summary of Firm Survey Results. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/list/dl/71-r02/03.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- Petts, R.J.; Knoester, C.; Waldfogel, J. Fathers’ Paternity Leave-Taking and Children’s Perceptions of Father-Child Relationships in the United States. Sex Roles 2020, 82, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaber, R.; Kopp, M.; Zähringer, A.; Mack, J.T.; Kress, V.; Garthus-Niegel, S. Paternal Leave and Father-Infant Bonding: Findings from the Population-Based Cohort Study DREAM. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 668028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parfitt, Y.; Ayers, S.; Pike, A.; Jessop, D.; Ford, E. A prospective study of the parent–baby bond in men and women 15 months after birth. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2014, 32, 441–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kerstis, B.; Aarts, C.; Tillman, C.; Persson, H.; Engström, G.; Edlund, B.; Öhrvik, J.; Sylvén, S.; Skalkidou, A. Association between parental depressive symptoms and impaired bonding with the infant. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2016, 19, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishigori, H.; Obara, T.; Nishigori, T.; Metoki, H.; Mizuno, S.; Ishikuro, M.; Sakurai, K.; Hamada, H.; Watanabe, Z.; Hoshiai, T.; et al. Mother-to-infant bonding failure and intimate partner violence during pregnancy as risk factors for father-to-infant bonding failure at 1 month postpartum: An adjunct study of the Japan Environment and Children’s Study. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020, 33, 2789–2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, R.A.; Hoffenkamp, H.N.; Tooten, A.; Braeken, J.; Vingerhoets, A.J.; Van Bakel, H.J. Child-rearing history and emotional bonding in parents of preterm and full-term infants. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2015, 24, 1715–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagihara, M. Current status of paternal involvement in parenting. Bull. Tenshi Coll. 2007, 7, 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Survey on Fathers of Infants. Available online: https://berd.benesse.jp/up_images/research/Father_03-ALL2.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- Frank, T.J.; Keown, L.J.; Dittman, C.K.; Sanders, M.R. Using Father Preference Data to Increase Father Engagement in Evidence-Based Parenting Programs. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2014, 24, 937–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salonen, A.H.; Kaunonen, M.; Astedt-Kurki, P.; Järvenpää, A.L.; Isoaho, H.; Tarkka, M.T. Parenting self-efficacy after childbirth. J. Adv. Nurs. 2009, 65, 2324–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadiroğlu, T.; Güdücü Tüfekci, F. Effect of Infant Care Training on Maternal Bonding, Motherhood Self-Efficacy, and Self-Confidence in Mothers of Preterm Newborns. Matern. Child Health J. 2021, 26, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosokawa, Y.; Okawa, S.; Hori, A.; Morisaki, N.; Takahashi, Y.; Fujiwara, T.; Nakayama, S.F.; Hamada, H.; Satoh, T.; Tabuchi, T. The prevalence of COVID-19 vaccination and vaccine hesitancy in pregnant women: An internet-based cross-sectional study in Japan. J. Epidemiol. 2022, JE20210458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaitsu, M.; Hosokawa, Y.; Okawa, S.; Hori, A.; Kobashi, G.; Tabuchi, T. Heated tobacco product use and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and low birth weight: Analysis of a cross-sectional, web-based survey in Japan. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e052976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, K.; Yamashita, H.; Conroy, S.; Marks, M.; Kumar, C. A Japanese version of Mother-to-Infant Bonding Scale: Factor structure, longitudinal changes and links with maternal mood during the early postnatal period in Japanese mothers. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2012, 15, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kumar, R.C. “Anybody’s child”: Severe disorders of mother-to-infant bonding. Br. J. Psychiatry 1997, 171, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, K.; Goto, A.; Takebayashi, Y.; Murakami, M.; Sasaki, M. Father-child bonding among Japanese fathers of infants: A municipal-based study at the time of the 4-month child health checkup. Infant Ment. Health J. 2021, 42, 705–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitamura, T.; Takegata, M.; Haruna, M.; Yoshida, K.; Yamashita, H.; Murakami, M.; Goto, Y. The Mother-Infant Bonding Scale: Factor Structure and Psychosocial Correlates of Parental Bonding Disorders in Japan. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2013, 24, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta, M.C.; Adema, W.; Baxter, J.; Han, W.J.; Lausten, M.; Lee, R.; Waldfogel, J. Fathers’ Leave and Fathers’ Involvement: Evidence from Four OECD Countries. Eur. J. Soc. Secur. 2014, 16, 308–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Petts, R.J.; Knoester, C. Paternity leave-taking and father engagement. J. Marriage Fam. 2018, 80, 1144–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Andrews, G.; Colpe, L.J.; Hiripi, E.; Mroczek, D.K.; Normand, S.L.; Walters, E.E.; Zaslavsky, A.M. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol. Med. 2002, 32, 959–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smilkstein, G. The family APGAR: A proposal for a family function test and its use by physicians. J. Fam. Pract. 1978, 6, 1231–1239. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, W.; Nutting, P.A.; Kelleher, K.J.; Werner, J.J.; Farley, T.; Stewart, L.; Hartsell, M.; Orzano, A.J. Does the family APGAR effectively measure family functioning? J. Fam. Pract. 2001, 50, 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Shinagawa, N. Social and medical discussion on Satogaeri Bunben. Nihonishikai Zasshi 1978, 80, 351–355. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.H.; Hyun, S.; Mittal, L.; Erdei, C. Psychological risks to mother-infant bonding during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatr. Res. 2021, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ono, H. Explorative study on the internal transformation process of men who took long-term parental leave. Jpn. Assoc. Ind. Organ. Psychol. J. 2019, 33, 35–50. [Google Scholar]

- Theeke, L.A.; Mallow, J.; Gianni, C.; Legg, K.; Glass, C. The experience of older women living with loneliness and chronic conditions in Appalachia. J. Rural Ment. Health 2015, 39, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guntuku, S.C.; Schneider, R.; Pelullo, A.; Young, J.; Wong, V.; Ungar, L.; Polsky, D.; Volpp, K.G.; Merchant, R. Studying expressions of loneliness in individuals using twitter: An observational study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e030355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kaufman, G. Barriers to equality: Why British fathers do not use parental leave. Community Work Fam. 2018, 21, 310–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, J.; Koslowski, A. Making use of work–family balance entitlements: How to support fathers with combining employment and caregiving. Community Work Fam. 2019, 22, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, S. Fathers’ Attitudes toward Taking Childcare Leave and Their Changes. J. Ohara Inst. Soc. Res. 2012, 61, 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Trumello, C.; Bramanti, S.M.; Lombardi, L.; Ricciardi, P.; Morelli, M.; Candelori, C.; Crudele, M.; Cattelino, E.; Baiocco, R.; Chirumbolo, A.; et al. COVID-19 and home confinement: A study on fathers, father-child relationships and child adjustment. Child Care Health Dev. 2021, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.N.; Armitage, C.J.; Tampe, T.; Dienes, K. Public perceptions and experiences of social distancing and social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic: A UK-based focus group study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e039334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone Gibbs, B.; Kline, C.E.; Huber, K.A.; Paley, J.L.; Perera, S. COVID-19 shelter-at-home and work, lifestyle and well-being in desk workers. Occup. Med. 2021, 71, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teti, D.M.; Gelfand, D.M. Behavioral competence among mothers of infants in the first year: The mediational role of maternal self-efficacy. Child Dev. 1991, 62, 918–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, D.W. UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): Reliability, validity, and factor structure. J. Personal. Assess. 1996, 66, 20–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Population Census. Available online: https://www.e-stat.go.jp/en (accessed on 28 December 2021).

- Basic Survey of Gender Equality in Employment Management. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/list/71-23.html (accessed on 28 December 2021).

- Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare. Outline of the Act on Childcare Leave, Caregiver Leave, and Other Measures for the Welfare of Workers Caring for Children or Other Family Members. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/bunya/koyoukintou/pamphlet/dl/02_en.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2022).

| Paternity Leave (−) (n = 794; 66.5%) | Paternity Leave (+) (n = 400; 33.5%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N or Mean | % or SD | N or Mean | % or SD | p Value b | ||

| Paternal age (year) | 35.5 | 5.2 | 35.4 | 5.3 | 0.80 | |

| Paternal educational attainment | University or more | 607 | 76.5 | 321 | 80.3 | |

| Some college | 93 | 11.7 | 43 | 10.8 | ||

| High school or less | 93 | 11.7 | 35 | 8.8 | ||

| Other | 1 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.3 | 0.37 | |

| Paternal job category | Employee | 739 | 93.1 | 384 | 96.0 | |

| Self-employed | 31 | 3.9 | 12 | 3.0 | ||

| Part-time or inoccupation | 24 | 3.0 | 4 | 1.0 | 0.06 | |

| Paternal K6 | 4.2 | 5.3 | 4.3 | 5.4 | 0.82 | |

| Household income (Million yen) | –4.9 | 115 | 14.5 | 46 | 11.5 | |

| 5.0–7.9 | 327 | 41.2 | 160 | 40.0 | ||

| 8.0– | 352 | 44.3 | 194 | 48.5 | 0.24 | |

| Maternal occupation | Inoccupation | 309 | 38.9 | 147 | 36.8 | |

| Having jobs (including maternal leave) | 485 | 61.1 | 253 | 63.3 | 0.53 | |

| Number of children | 1 | 383 | 48.2 | 205 | 51.3 | |

| 2 | 291 | 36.7 | 151 | 37.8 | ||

| 3 | 91 | 11.5 | 37 | 9.3 | ||

| 4– | 29 | 3.7 | 7 | 1.8 | 0.17 | |

| Youngest child’s age | <6 months | 224 | 28.2 | 115 | 28.8 | |

| <12 months | 279 | 35.1 | 139 | 34.8 | ||

| <18 months | 211 | 26.6 | 110 | 27.5 | ||

| <24 months | 80 | 10.1 | 36 | 9.0 | 0.93 | |

| Family function (Family APGAR) | 7.1 | 2.9 | 6.9 | 3.1 | 0.33 | |

| Social support from grandparents | No | 230 | 29.0 | 168 | 42.0 | |

| Yes | 564 | 71.0 | 232 | 58.0 | <0.001 * | |

| Satogaeri bunben a | No | 545 | 68.6 | 271 | 67.8 | |

| Yes | 249 | 31.4 | 129 | 32.3 | 0.10 | |

| Crude Model | Adjusted Model | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | 95% CI | β | 95% CI | ||||||

| Outcome | |||||||||

| Total score | Paternity leave | 0.61 * | 0.05 | to | 1.17 | 0.51 * | 0.06 | to | 0.96 |

| Lack of affection | Paternity leave | 0.15 | −0.12 | to | 0.42 | 0.10 | −0.13 | to | 0.34 |

| Anger and rejection | Paternity leave | 0.29 * | 0.02 | to | 0.56 | 0.26 * | 0.03 | to | 0.49 |

| Infant Age | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <6 Months (n = 339) | 6–12 Months (n = 418) | 12–18 Months (n = 321) | 18–24 Months (n = 116) | p for Trend | |||||||||

| Outcome | Mean (SD) | β | 95% CI | Mean (SD) | β | 95% CI | Mean (SD) | β | 95% CI | Mean (SD) | β | 95% CI | |

| MIBS-J | 4.7 (4.7) | 0.42 | −0.44 to 1.28 | 4.1 (4.6) | 0.58 | −0.22 to 1.38 | 4.6 (4.9) | 0.48 | −0.36 to 1.31 | 5.0 (4.3) | 0.66 | −0.87 to 2.20 | 0.98 |

| LA | 1.8 (2.3) | 0.09 | −0.36 to 0.55 | 1.5 (2.2) | 0.22 | −0.20 to 0.63 | 1.7 (2.3) | −0.03 | −0.48 to 0.41 | 1.7 (2.0) | 0.21 | −0.53 to 0.94 | 0.33 |

| AR | 2.3 (2.2) | 0.17 | −0.27 to 0.61 | 2.0 (2.3) | 0.28 | −0.13 to 0.68 | 2.4 (2.3) | 0.34 | −0.09 to 0.77 | 2.7 (2.1) | 0.27 | −0.52 to 1.06 | 0.19 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Terada, S.; Fujiwara, T.; Obikane, E.; Tabuchi, T. Association of Paternity Leave with Impaired Father–Infant Bonding: Findings from a Nationwide Online Survey in Japan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4251. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074251

Terada S, Fujiwara T, Obikane E, Tabuchi T. Association of Paternity Leave with Impaired Father–Infant Bonding: Findings from a Nationwide Online Survey in Japan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(7):4251. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074251

Chicago/Turabian StyleTerada, Shuhei, Takeo Fujiwara, Erika Obikane, and Takahiro Tabuchi. 2022. "Association of Paternity Leave with Impaired Father–Infant Bonding: Findings from a Nationwide Online Survey in Japan" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 7: 4251. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074251

APA StyleTerada, S., Fujiwara, T., Obikane, E., & Tabuchi, T. (2022). Association of Paternity Leave with Impaired Father–Infant Bonding: Findings from a Nationwide Online Survey in Japan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(7), 4251. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074251