Depression Symptoms among Family Members of Nyaope Users in the City of Tshwane, South Africa

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Study Setting, Sampling, and Sample Size

2.4. Study Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.5. Data Collection Tools

2.6. Data Analysis

2.7. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Participants

3.2. Characteristics of the Nyaope Users

3.3. Prevalence of Depression Symptoms

3.4. Factors Associated with Depression

3.5. Multiple Regression–Depression Symptoms

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

5.1. Recommendations

5.2. Limitations of the Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Day, C.; Gray, A. Health and related indicators. S. Afr. Health Rev. 2014, 2014, 197–332. [Google Scholar]

- Barron, P.; Padarath, A. Twenty years of the South African Health Review. S. Afr. Health Rev. 2017, 2017, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Peltzer, K.; Ramlagan, S.; Johnson, B.D.; Phaswana-Mafuya, N. Illicit drug use and treatment in South Africa: A review. Subst. Use Misuse 2010, 45, 2221–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mokwena, K.E.; Huma, M. Experiences of nyaope users in three provinces of South Africa: Substance abuse. Afr. J. Phys. Health Educ. Recreat. Danc. 2014, 20 (Suppl. 1), 352–363. [Google Scholar]

- Benishek, L.A.; Kirby, K.C.; Dugosh, K.L. Prevalence and frequency of problems of concerned family members with a substance-using loved one. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abus. 2011, 37, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Substance Abuse Treatment and Family Therapy; Report No.: (SMA) 04-3957; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Rockville, MD, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Usher, K.; Jackson, D.; O’Brien, L. Shattered dreams: Parental experiences of adolescent substance abuse. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2007, 16, 422–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zauszniewski, J.A.; Bekhet, A.K. Factors associated with the emotional distress of women family members of adults with serious mental illness. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2014, 28, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groenewald, C.; Bhana, A. “It was bad to see my [Child] doing this”: Mothers’ experiences of living with adolescents with substance abuse problems. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2016, 14, 646–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, D.K.; Becan, J.E.; Landrum, B.; Joe, G.W.; Flynn, P.M. Screening and assessment tools for measuring adolescent client needs and functioning in substance abuse treatment. Subst. Use Misuse 2014, 49, 902–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rosenbloom, T.; Beigel, A.; Perlman, A.; Eldror, E. Parental and offspring assessment of driving capability under the influence of drugs or alcohol: Gender and inter-generational differences. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2010, 42, 2125–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, M.H.; Meade, C.S.; Kimani, S.; MacFarlane, J.C.; Choi, K.W.; Skinner, D.; Sikkema, K.J. The impact of methamphetamine (“tik”) on a peri-urban community in Cape Town, South Africa. Int. J. Drug Policy 2014, 25, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Orford, J.; Natera, G.; Davies, J.; Nava, A.; Mora, J.; Rigby, K.; Velleman, R. Stresses and strains for family members living with drinking or drug problems in England and Mexico. Salud Ment. 2013, 21, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Orford, J.; Copello, A.; Velleman, R.; Templeton, L. Family members affected by a close relative’s addiction: The stress-strain-coping-support model. Drugs Educ. Prev. Policy 2010, 17 (Suppl. 1), 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Solati, K.; Hasanpour-Dehkordi, A. Study of Association of Substance Use Disorders with Family Members’ Psychological Disorders. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2017, 11, VC12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panayiotopoulos, C.; Pavlakis, A.; Apostolou, M. The family burden of schizophrenic patients and the welfare system; the case of Cyprus. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2013, 7, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Der Sanden, R.L.; Bos, A.E.; Stutterheim, S.E.; Pryor, J.B.; Kok, G. Stigma by association among family members of people with a mental illness: A qualitative analysis. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 25, 400–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kessler, R.C.; Aguilar-Gaxiola, S.; Alonso, J.; Chatterji, S.; Lee, S.; Ormel, J.; Wang, P.S. The global burden of mental disorders: An update from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) surveys. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2009, 18, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Merikangas, K.R.; Nakamura, E.F.; Kessler, R.C. Epidemiology of mental disorders in children and adolescents. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2009, 11, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Paruk, S.; Burns, J.K.; Caplan, R. Cannabis use and family history in adolescent first-episode psychosis in Durban, South Africa. J. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2013, 25, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saban, A.; Flisher, A.J.; Grimsrud, A.; Morojele, N.; London, L.; Williams, D.R.; Stein, D.J. The association between substance use and common mental disorders in young adults: Results from the South African Stress and Health (SASH) Survey. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2014, 17 (Suppl. 1), 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Mental Health Action Plan 2013-2020; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B.E.; Gilman, A.B.; Kosterman, R.; Hill, K.G. Longitudinal associations among depression, substance abuse, and crime: A test of competing hypotheses for driving mechanisms. J. Crim. Justice 2019, 62, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curran, E.; Adamson, G.; Stringer, M.; Rosato, M.; Leavey, G. The severity of mental illness as a result of multiple childhood adversities: US National Epidemiologic Survey. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2016, 51, 647–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashtari, M.; Cervellione, K.; Cottone, J.; Ardekani, B.A.; Kumra, S. Diffusion abnormalities in adolescents and young adults with a history of heavy cannabis use. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2009, 43, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lynch, F.L.; Clarke, G.N. Estimating the economic burden of depression in children and adolescents. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2006, 31, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merikangas, K.R.; He, J.-P.; Brody, D.; Fisher, P.W.; Bourdon, K.; Koretz, D.S. Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders among US children in the 2001–2004 NHANES. Paediatrics 2010, 125, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bair, M.J.; Wu, J.; Damush, T.M.; Sutherland, J.M.; Kroenke, K. Association of depression and anxiety alone and in combination with chronic musculoskeletal pain in primary care patients. Psychosom. Med. 2008, 70, 890–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Petersen, I.; Lund, C. Mental health service delivery in South Africa from 2000 to 2010: One step forward, one step back. S. Afr. Med. J. 2011, 101, 751–757. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbody, S.; Sheldon, T.; Wessely, S. Should we screen for depression? BMJ 2006, 332, 1027–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Greenberg, P.E.; Birnbaum, H.G. The economic burden of depression in the US: Societal and patient perspectives. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2005, 6, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobocki, P.; Jönsson, B.; Angst, J.; Rehnberg, C. Cost of depression in Europe. J. Ment. Health Policy Econ. 2006, 9, 87–98. [Google Scholar]

- Sobocki, P.; Lekander, I.; Borgström, F.; Ström, O.; Runeson, B. The economic burden of depression in Sweden from 1997 to 2005. Eur. Psychiatry 2007, 22, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, R. The Family and Family Structure Classification Redefined for the Current Times. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2013, 2, 306–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lander, L.; Howsare, J.; Byrne, M. The impact of substance use disorders on families and children: From theory to practice. Soc. Work. Public Health 2013, 28, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoeck, S.; Van Hal, G. Experiences of parents of substance-abusing young people attending support groups. Arch. Public Health 2012, 70, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mathibela, F. Experiences, Challenges and Coping Strategies of Parents Living with Teenagers Abusing Chemical Substances in Ramotse. Master’s Thesis, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mathibela, F.; Skhosana, R. Challenges faced by parents raising adolescents abusing substances: Parents’ voices. Soc. Work. 2019, 55, 87–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, E.; Rambau, E. The effect of a latchkey situation on a child’s educational success. S. Afr. J. Educ. 2011, 31, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, L.; Mavungu, E.M. ‘Children, families and the conundrum about men’: Exploring factors contributing to father absence in South Africa and its implications for social and care policies. S. Afr. Rev. Sociol. 2016, 47, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokwena, K.; Morojele, N. Unemployment and unfavourable social environment as contributory factors to nyaope use in three provinces of South Africa: Substance abuse. Afr. J. Phys. Health Educ. Recreat. Danc. 2014, 20 (Suppl. 1), 374–384. [Google Scholar]

- Osborn, T.L.; Venturo-Conerly, K.E.; Wasil, A.R.; Schleider, J.L.; Weisz, J.R. Depression and anxiety symptoms, social support, and demographic factors among Kenyan high school students. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2020, 29, 1432–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mokwena, K.; Makuwerere, N. The Novel Psychoactive Substance Nyaope Contributes to Mental Disorders for Family Members: A Qualitative Study in Gauteng Province, South Africa. J. Drug Alcohol Res. 2021, 10, 236133. [Google Scholar]

- Cloete, A. Youth unemployment in South Africa. A theological reflection through the lens of human dignity. Missionalia 2015, 43, 513–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, P.R. Why is depression more prevalent in women? J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2015, 40, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, M.; Sharma, N.; Yadava, A. Parental styles and depression among adolescents. J. Indian Acad. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 37, 60–68. [Google Scholar]

- Anlı, İ.; Karslı, T.A. Perceived parenting style, depression and anxiety levels in a Turkish late-adolescent population. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2010, 2, 724–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mashaba, B.L.; Moodley, S.V.; Ledibane, N.R. Screening for depression at the primary care level: Evidence for policy decision-making from a facility in Pretoria, South Africa. S. Afr. Fam. Pract. 2021, 63, 5217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motlhatlhedi, K.; Molebatsi, K.; Wambua, G.N. Prevalence of depressive symptoms in urban primary care settings: Botswana. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2021, 13, 2822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Relationship to nyaope user | ||

| Parents | 165 | 42 |

| Siblings | 137 | 35 |

| Other (aunts, uncles, and cousins) | 55 | 14 |

| Grandparents | 33 | 9 |

| 390 | 100 | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 304 | 78 |

| Male | 86 | 22 |

| 390 | 100 | |

| Age Categories | ||

| 11–20 | 16 | 4 |

| 21–30 | 63 | 16 |

| 31–40 | 74 | 19 |

| 41–50 | 56 | 14 |

| 51–60 | 84 | 22 |

| 61–70 | 61 | 16 |

| 71–80 | 28 | 7.2 |

| 81–90 | 7 | 1.8 |

| 389 | 100 | |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single | 218 | 56 |

| Married | 99 | 25 |

| Widowed | 60 | 15 |

| Divorced | 13 | 4 |

| 390 | 100 | |

| Highest level of education obtained | ||

| Secondary | 242 | 62 |

| Primary | 80 | 21 |

| Tertiary | 52 | 13 |

| None | 14 | 3.5 |

| Missing data | 2 | 0.5 |

| 390 | 100 | |

| Employment status | ||

| Unemployed | 180 | 46 |

| Employed | 104 | 27 |

| Pensioner | 95 | 24 |

| Student | 10 | 2.7 |

| Missing data | 1 | 0.3 |

| 390 | 100 | |

| Language | ||

| Setswana Sepedi | 130 120 | 33 31 |

| isiZulu | 48 | 12 |

| Xitsonga | 27 | 7 |

| isiNdebele | 23 | 6 |

| Sesotho | 21 | 5.4 |

| isiXhosa | 7 | 2 |

| Tshivenda | 4 | 1 |

| siSwati | 3 | 0.8 |

| Missing data | 3 | 0.8 |

| Afrikaans | 2 | 0.5 |

| English | 2 | 0.5 |

| 390 | 100 | |

| Location of the participants and nyaope users | ||

| Soshanguve | 97 | 25 |

| Ga-Rankuwa | 94 | 24 |

| Mamelodi | 80 | 21 |

| Hammanskraal | 75 | 19 |

| Winterveldt | 21 | 5 |

| Atteridgeville | 9 | 2 |

| Pretoria North | 6 | 2 |

| Mabopane | 5 | 1 |

| Olievenhoutbosch | 3 | 0.7 |

| 390 | 100 | |

| Variable | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 363 | 93 |

| Female | 27 | 7 |

| 390 | 100 | |

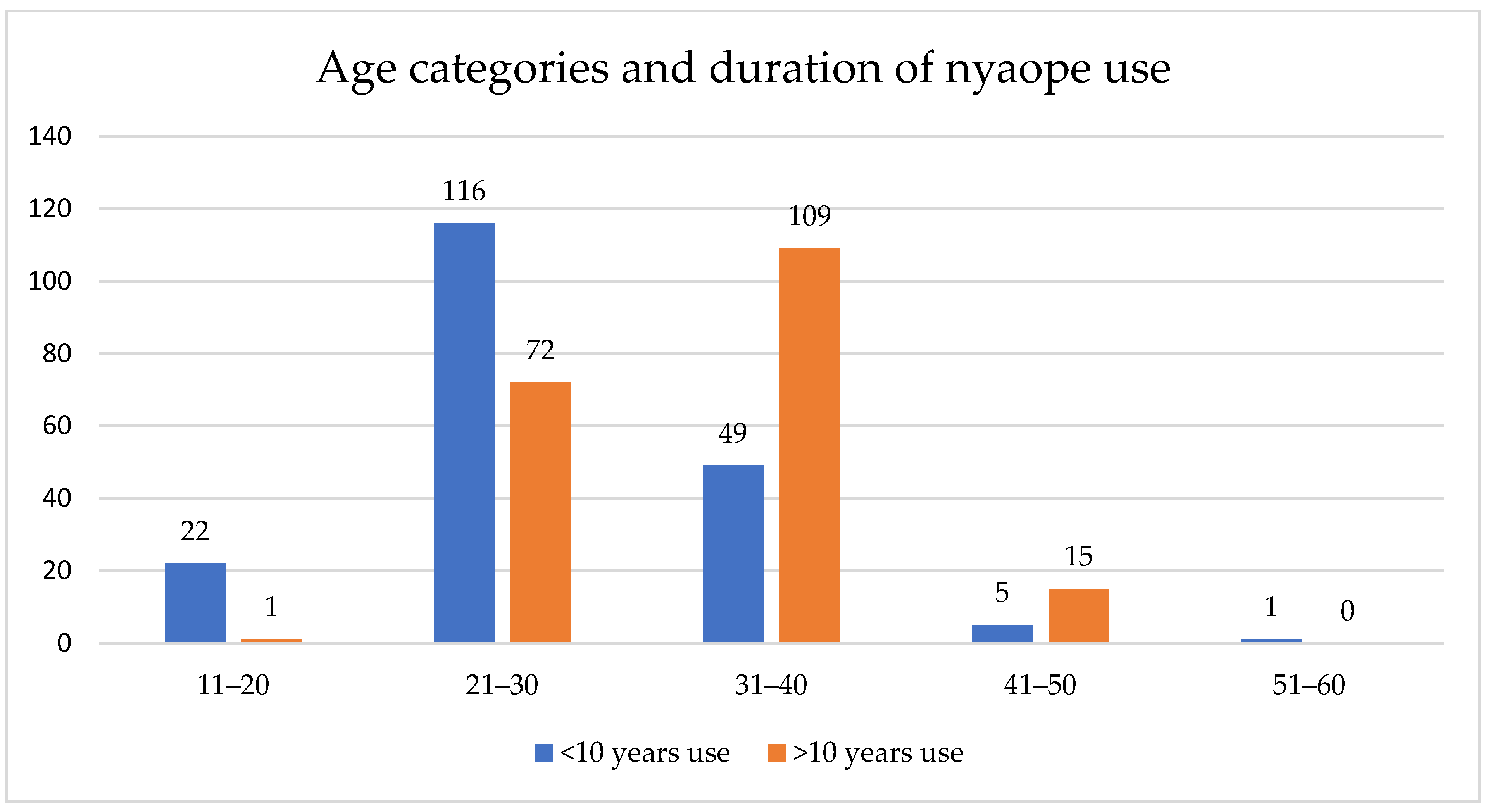

| Age category | ||

| 21–30 | 188 | 48.2 |

| 31–40 | 158 | 40.5 |

| 11–20 | 23 | 5.9 |

| 41–50 | 20 | 5.1 |

| 51–60 | 1 | 0.3 |

| 390 | 100 | |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 285 | 73 |

| Married | 5 | 27 |

| 390 | 100 | |

| Highest level of education obtained | ||

| Secondary | 341 | 87.4 |

| Primary | 32 | 8.2 |

| Tertiary | 14 | 3.6 |

| Missing data | 3 | 0.8 |

| 390 | 100 | |

| Employment status | ||

| Unemployed | 357 | 92 |

| Employed | 29 | 7 |

| Student | 4 | 1 |

| 390 | 100 | |

| <10 Years’ Use | >10 Years’ Use | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ga-Rankuwa | 65 | 29 | 94 |

| Hammanskraal | 48 | 27 | 75 |

| Soshanguve | 33 | 64 | 97 |

| Mamelodi | 29 | 51 | 80 |

| Winterveldt | 6 | 15 | 21 |

| Atteridgeville | 5 | 4 | 9 |

| Mabopane | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| Pretoria North Olivenhoutbosch | 3 1 | 3 2 | 6 3 |

| n = 193 | n = 197 | n = 390 |

| PHQ-9 Ranges | Classification | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0–4 | None | 201 | 51 |

| 5–9 | Mild | 83 | 21 |

| 10–19 | Moderate | 65 | 17 |

| 20–29 | Severe | 41 | 11 |

| 390 | 100 |

| Variable | p-Value |

|---|---|

| Participant-related variables | |

| Area/place of residence/location | 0.44 |

| Age of participant | 0.03 * |

| Gender of participant | 0.08 |

| Language of participant | 0.83 |

| Religion of participant | 0.03 * |

| Relationship with nyaope user | 0.02 * |

| Marital status of the participant | 0.01 * |

| Highest Education of the participant | 0.52 |

| Employment status of the participant | 0.76 |

| User-related variables | |

| Age of user | 0.10 |

| Gender of user | 0.27 |

| Number of years using nyaope | 0.58 |

| Marital status of the user | 0.69 |

| Highest level of education of the user | 0.03 * |

| Employment status of the user | 0.756 |

| Number of times admitted for rehabilitation | 0.07 |

| Lives at home | 0.13 |

| Number of times arrested | 0.62 |

| Variable | p-Value |

|---|---|

| Participant-related variables | |

| Age of the participant | 0.18 |

| Gender of the participant | 0.15 |

| Religion of the participant | 0.03 * |

| Relationship with nyaope user | 0.1 |

| Marital status of the participant | 0.01 ** |

| User-related variables | |

| Age of user | 0.12 |

| Highest level of education of the user | 0.02 * |

| Number of times admitted for rehabilitation | 0.51 |

| Lives at home | 0.16 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Madiga, M.C.; Mokwena, K. Depression Symptoms among Family Members of Nyaope Users in the City of Tshwane, South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4097. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074097

Madiga MC, Mokwena K. Depression Symptoms among Family Members of Nyaope Users in the City of Tshwane, South Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(7):4097. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074097

Chicago/Turabian StyleMadiga, Maphuti Carol, and Kebogile Mokwena. 2022. "Depression Symptoms among Family Members of Nyaope Users in the City of Tshwane, South Africa" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 7: 4097. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074097

APA StyleMadiga, M. C., & Mokwena, K. (2022). Depression Symptoms among Family Members of Nyaope Users in the City of Tshwane, South Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(7), 4097. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074097