Peer Power! Secure Peer Attachment Mediates the Effect of Parental Attachment on Depressive Withdrawal of Teenagers

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Do the Levels of Teenagers’ Withdrawal Vary According to Different Attachment Internal Working Models, Particularly to Preoccupied One?

1.2. Do Higher Parental and Peer Attachment Security Independently Predict Lower Teenagers’ Withdrawal?

1.3. Is Peer Attachment a Mediator in the Relationship between Parental Attachment and Teenagers’ Withdrawal?

1.4. The Current Study

- RQ1: Do the levels of withdrawal vary according to the different IWMs?

- RQ2: Are withdrawal levels higher in adolescents with higher levels of insecurity, particularly preoccupation?

- RQ3: Do higher parental and peer attachment security independently predict lower withdrawal of adolescents?

- RQ4: Is peer attachment a mediator in the relationship between parental attachment and teenagers’ withdrawal?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Withdrawal

2.2.2. Attachment IWMs and Attachment to Parents and Peers

2.2.3. Demographic Information

2.3. Analytic Plan

3. Results

3.1. Differences in Withdrawal According to the Attachment IWM

3.2. Prediction of Withdrawal Based on Parent and Peer Attachment

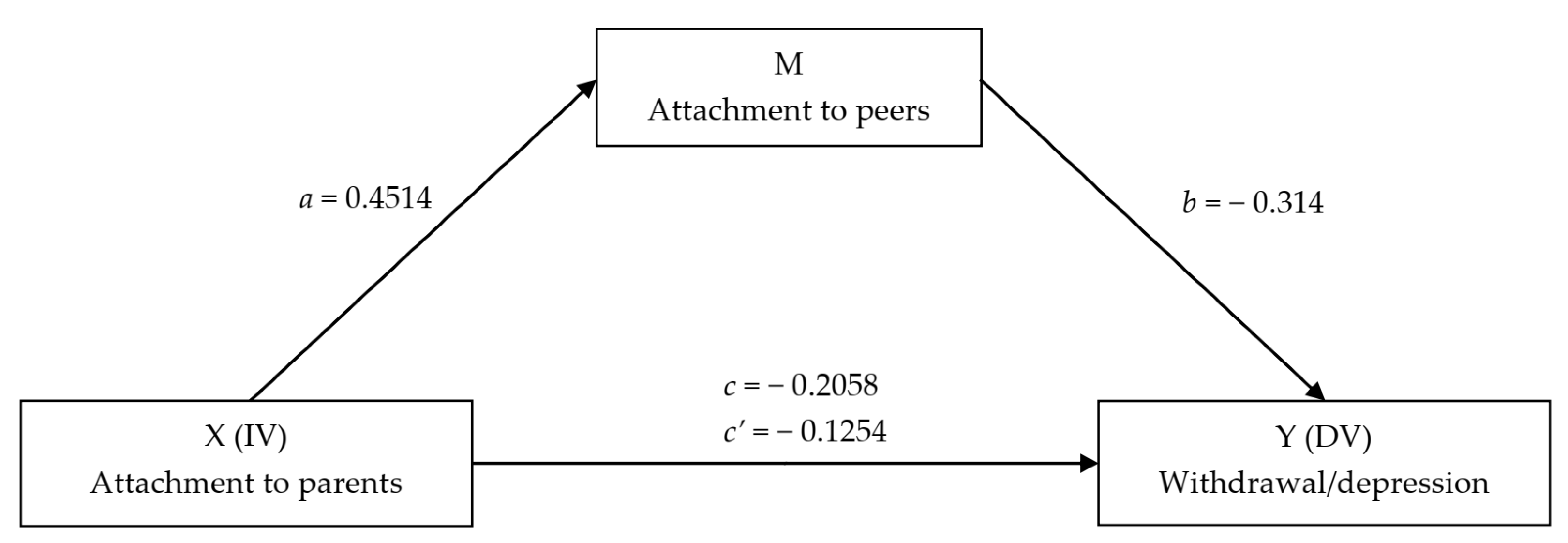

3.3. Mediation Model

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Lines of Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Channel, R.L. A Review of the Research on Social Withdrawal in Children and Adolescents. 1998. Available online: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/grp/478 (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Rubin, K.H.; Chen, X.; Hymel, S. Socioemotional characteristics of withdrawn and aggressive children. Merrill-Palmer Q. (1982) 1993, 39, 518–534. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, S.J.; Conway, C.C.; Hammen, C.L.; Brennan, P.A.; Najman, J.M. Childhood social withdrawal, interpersonal impairment, and young adult depression: A mediational model. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2011, 39, 1227–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rubin, K.H.; Coplan, R.J. Paying Attention to and Not Neglecting Social Withdrawal and Social Isolation. Merrill-Palmer Q. 2004, 50, 506–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, K.H.; Bowker, J.; Gazelle, H. Social withdrawal in childhood and adolescence: Peer relationships and social competence. In The Development of Shyness and Social Withdrawal; Rubin, K.H., Coplan, R.J., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 131–156. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach, T.M.; Rescorla, L.A. Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles; University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families: Burlington, VT, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Finning, K.; Ukoumunne, O.C.; Ford, T.; Danielsson-Waters, E.; Shaw, L.; De Jager, I.R.; Moore, D.A. The association between child and adolescent depression and poor attendance at school: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 245, 928–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubin, K.H.; Bukowski, W.M.; Parker, J.G. Peer interactions, relationships, and groups. In Handbook of Child Psychology; Damon, W., Lerner, R.M., Eisenberg, N., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 517–645. [Google Scholar]

- Prior, M.; Smart, D.; Sanson AN, N.; Oberklaid, F. Does shy-inhibited temperament in childhood lead to anxiety problems in adolescence? J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2000, 39, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Högnäs, R.S.; Almquist, Y.B.; Modin, B. Adolescent social isolation and premature mortality in a Swedish birth cohort. J. Popul. Res. 2020, 37, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaneko, S. Japan’s ‘Socially Withdrawn Youths’ and Time Constraints in Japanese Society: Management and conceptualization of time in a support group for ‘hikikomori’. Time Soc. 2006, 15, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pozza, A.; Coluccia, A.; Kato, T.; Gaetani, M.; Ferretti, F. The ‘Hikikomori’syndrome: Worldwide prevalence and co-occurring major psychiatric disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis protocol. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e025213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, J.; Rapee, R.M.; Oh, K.J.; Moon, H.S. Retrospective report of social withdrawal during adolescence and current maladjustment in young adulthood: Cross-cultural comparisons between Australian and South Korean students. J. Adolesc. 2008, 31, 543–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T.A.; Shinfuku, N.; Sartorius, N.; Kanba, S. Are Japan’s hikikomori and depression in young people spreading abroad? Lancet 2011, 378, 1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.M.; Wong, P.W. Youth social withdrawal behavior (hikikomori): A systematic review of qualitative and quantitative studies. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2015, 49, 595–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaan, V.K.; Schulz, A.; Schächinge, H.; Vögele, C. Parental divorce is associated with an increased risk to develop mental disorders in women. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 257, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malagón-Amor, Á.; Martín-López, L.M.; Córcoles, D.; González, A.; Bellsolà, M.; Teo, A.R.; Bulbena, A.; Pérez, V.; Bergé, D. Family Features of Social Withdrawal Syndrome (Hikikomori). Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Muzi, S.; Sansò, A.; Pace, C.S. What’s Happened to Italian Adolescents During the COVID-19 Pandemic? A Preliminary Study on Symptoms, Problematic Social Media Usage, and Attachment: Relationships and Differences with Pre-pandemic Peers. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 590543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orgilés, M.; Morales, A.; Del Vecchio, E.; Mazzeschi, C.; Espada, J.P. Immediate psychological effects of the COVID-19 quarantine in youth from Italy and Spain. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, A.E.; Allen, K.R.; Smith, J.Z. Divorced and separated parents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Fam. Process 2021, 60, 866–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çivitci, N.; Çivitci, A.; Fiyakali, N.C. Loneliness and life satisfaction in adolescents with divorced and non-divorced parents. Kuram Ve Uygul. Eğitim Bilimleri 2009, 9, 513–525. [Google Scholar]

- Crowell, J.A.; Treboux, D.; Brockmeyer, S. Parental divorce and adult children’s attachment representations and marital status. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2009, 11, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss. Vol. 3: Loss, Sadness and Depression; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Groh, A.M.; Fearon, R.P.; van IJzendoorn, M.H.; Bakermans- Kranenburg, M.J.; Roisman, G.I. Attachment in the early life course: Meta-analytic evidence for its role in socioemotional development. Child Dev. Perspect. 2017, 11, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulincer, M.; Shaver, P.R. An attachment perspective on psychopathology. World Psychiatry 2012, 11, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ainsworth, M.D.S.; Blehar, M.C.; Waters, E.; Wall, S.N. Patterns of Attachment: A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation; Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- George, C.; Main, M.; Kaplan, N. Adult Attachment Interview (AAI); Unpublished manual; University of Berkeley: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Muzi, S.; Pace, C.S. Multiple facets of attachment in residential-care, late adopted, and community adolescents: An interview-based comparative study. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2021, 24, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.P.; Porter, M.; McFarland, C.; McElhaney, K.B.; Marsh, P. The relation of attachment security to adolescents’ paternal and peer relationships, depression, and externalizing behavior. Child Dev. 2007, 78, 1222–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Oldfield, J.; Humphrey, N.; Hebron, J. The role of parental and peer attachment relationships and school connectedness in predicting adolescent mental health outcomes. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2016, 21, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieg, A.; Dickie, J.R. Attachment and hikikomori: A psychosocial developmental model. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2013, 59, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogino, T. Managing categorization and social withdrawal in Japan: Rehabilitation process in a private support group for hikikomorians. Int. J. Jpn. Sociol. 2004, 13, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlong, A. The Japanese hikikomori phenomenon: Acute social withdrawal among young people. Sociol. Rev. 2008, 56, 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, S.; Brumariu, L.E.; Villani, V.; Atkinson, L.; Lyons-Ruth, K. Representational and questionnaire measures of attachment: A meta-analysis of relations to child internalizing and externalizing problems. Psychol. Bull. 2016, 142, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, H.; Steele, M. The construct of coherence as an indicator of attachment security in middle childhood: The Friends and Family Interview. In Attachment in Middle Childhood; Kerns, K., Richardson, R., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 137–160. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, J.P.; Tan, J.S. The multiple facets of attachment in adolescence. In Handbook of Attachment, 3rd ed.; Cassidy, J., Shaver, P.R., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 399–415. [Google Scholar]

- Pace, C.S.; Di Folco, S.; Guerriero, V.; Muzi, S. Late-adopted children grown up: A long-term longitudinal study on attachment patterns of adolescent adoptees and their adoptive mothers. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2019, 21, 372–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moretti, M.M.; Peled, M. Adolescent-parent attachment: Bonds that support healthy development. Paediatr. Child Health 2004, 9, 551–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mónaco, E.; de la Barrera, U.; Castilla, I.M. Parents and peer attachment and their relationship with emotional problems in adolescence: Is stress mediating? Rev. De Psicol. Clínica Con Niños Y Adolesc. 2021, 8, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.T.; Albert, A.B.; Dwelle, D.G. Parental and peer support as predictors of depression and self-esteem among college students. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2014, 55, 120–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth-LaForce, C.; Oxford, M.L. Trajectories of social withdrawal from grades 1 to 6: Prediction from early parenting, attachment, and temperament. Dev. Psychol. 2008, 44, 1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cavanaugh, A.M.; Buehler, C. Adolescent loneliness and social anxiety: The role of multiple sources of support. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2016, 33, 149–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Roekel, E.; Goossens, L.; Scholte, R.H.; Engels, R.C.; Verhagen, M. The dopamine D2 receptor gene, perceived parental support, and adolescent loneliness: Longitudinal evidence for gene–environment interactions. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2011, 52, 1044–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, O.; Choi, J.; Kim, J. A longitudinal study of the effects of negative parental child-rearing attitudes and positive peer relationships on social withdrawal during adolescence: An application of a multivariate latent growth model. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2020, 25, 448–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roelofs, J.; Lee, C.; Ruijten, T.; Lobbestael, J. The mediating role of early maladaptive schemas in the relation between quality of attachment relationships and symptoms of depression in adolescents. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2011, 39, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Machado, A.K.; Wendt, A.; Ricardo, L.I.; Marmitt, L.P.; Martins, R.C. Are parental monitoring and support related with loneliness and problems to sleep in adolescents? Results from the Brazilian School-based Health Survey. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 119, 105682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, S.A.N.; Faraco, A.M.X.; Vieira, M.L. Attachment and Parental Practices as Predictors of Behavioral Disorders in Boys and Girls1. Paidéia (Ribeirão Preto) 2013, 23, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, O.; Santos, A.; Freitas, M.; Rubin, K.; Verissimo, M. Social Withdrawal, Attachment and Depression in Portuguese Adolescents [Poster presentation]. In Proceedings of the International Attachment Conference IAC 2017, London, UK, 29 June–1 July 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosacki, S.; Dane, A.; Marini, Z.; YLC-CURA. Peer relationships and internalizing problems in adolescents: Mediating role of self-esteem. Emot. Behav. Difficulties 2007, 12, 261–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzi, S.; Pace, C.S.; Steele, H. The Friends and Family Interview Converges with the Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment in Community but Not Institutionalized Adolescents. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2022, 31, 518–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armsden, G.C.; Greenberg, M.T. The Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment: Individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 1987, 16, 427–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowker, J.C.; White, H.I. Studying peers in research on social withdrawal: Why broader assessments of peers are needed. Child Dev. Perspect. 2021, 15, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucktong, A.; Salisbury, T.T.; Chamratrithirong, A. The impact of parental, peer and school attachment on the psychological well-being of early adolescents in Thailand. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2018, 23, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pallini, S.; Baiocco, R.; Schneider, B.H.; Madigan, S.; Atkinson, L. Early child–parent attachment and peer relations: A meta-analysis of recent research. J. Fam. Psychol. 2014, 28, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benson, M.J.; McWey, L.M.; Ross, J.J. Parental attachment and peer relations in adolescence: A meta-analysis. Res. Hum. Dev. 2006, 3, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, H.L. The relationship between parental attachments, perceptions of social supports and depressive symptoms in adolescent boys and girls. Diss. Abstr. Int. Sect. A Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2000, 61, 513. [Google Scholar]

- Laible, D.J.; Carlo, G.; Raffaelli, M. The differential relations of parent and peer attachment to adolescent adjustment. J. Youth Adolesc. 2000, 29, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frigerio, A.; Rucci, P.; Goodman, R.; Ammaniti, M.; Carlet, O.; Cavolina, P.; Molteni, M. Prevalence and correlates of mental disorders among adolescents in Italy: The PrISMA study. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2009, 18, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, C.S.; Muzi, S.; Steele, H. Adolescents’ attachment: Content and discriminant validity of the friends and family interview. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2020, 29, 1173–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Maheux, A.J.; Nesi, J.; Galla, B.M.; Roberts, S.R.; Choukas-Bradley, S. # Grateful: Longitudinal Associations Between Adolescents’ Social Media Use and Gratitude During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Res. Adolesc. 2021, 31, 734–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loades, M.E.; Chatburn, E.; Higson-Sweeney, N.; Reynolds, S.; Shafran, R.; Brigden, A.; Crawley, E. Rapid systematic review: The impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of COVID-19. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 59, 1218–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, K.; Schwartz, C.; Towner, E.; Kasparian, N.A.; Callaghan, B. Parenting under pressure: A mixed-methods investigation of the impact of COVID-19 on family life. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2021, 5, 100161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, S.; Mikocka-Walus, A.; Klas, A.; Olive, L.; Sciberras, E.; Karantzas, G.; Westrupp, E.M. From ‘It has stopped our lives’ to ‘Spending more time together has strengthened bonds’: The varied experiences of Australian families during COVID-19. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alter Agents for Snapchat The Friendship Report 2020. Insights on How to Maintain Friendships, Navigate Endships, and Stay Connected in COVID-19. Available online: https://images.ctfassets.net/inb32lme5009/5MJXbvGtFXFXbdofsiYbp/f24adc95cfad109994ebb8f9467bc842/Snap_Inc._The_Friendship_Report_2020_-Global-.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Brady, R.; Maccarrone, A.; Holloway, J.; Gunning, C.; Pacia, C. Exploring Interventions Used to Teach Friendship Skills to Children and Adolescents with High-Functioning Autism: A Systematic Review. Rev. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2020, 7, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, D.R.; Simpkins, S.D.; Vest, A.E.; Price, C.D. The contribution of extracurricular activities to adolescent friendships: New insights through social network analysis. Dev. Psychol. 2011, 47, 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moretti, M.M.; Obsuth, I. Effectiveness of an attachment-focused manualized intervention for parents of teens at risk for aggressive behaviour: The Connect Program. J. Adolesc. 2009, 32, 1347–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Harmelen, A.L.; Blakemore, S.J.; Goodyer, I.M.; Kievit, R.A. The interplay between adolescent friendship quality and resilient functioning following childhood and adolescent adversity. Advers. Resil. Sci. 2021, 2, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T.A.; Kanba, S.; Teo, A.R. Hikikomori: Multidimensional understanding, assessment, and future international perspectives. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2019, 73, 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P.W. Potential changes to the hikikimori phenomenon in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic. Asian J. Psychiatry 2020, 54, 102288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, C.S.; Muzi, S.; Rogier, G.; Meinero, L.L.; Marcenaro, L. The Adverse Childhood Experiences—International Questionnaire (ACE-IQ) in community samples around the world: A systematic review (Part I). Child Abuse Negl. under review.

- Velotti, P.; Beomonte Zobel, S.; Rogier, G.; Tambelli, R. Exploring relationships: A systematic review on intimate partner violence and attachment. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total | Parents | Differences | Relation with Age | Gender | Differences | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Together | Separated | Boys | Girls | ||||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | t(88) | r | M | SD | M | SD | t(89) | |

| Withdrawal | 3.55 | 2.49 | 3.49 | 2.54 | 3.76 | 2.31 | −0.40 | −0.01 | 3.26 | 2.71 | 3.70 | 2.33 | −0.82 |

| F/S | 3.22 | 0.77 | 3.22 | 0.77 | 3.18 | 0.79 | 0.20 | 0.12 | 3.01 | 0.81 | 3.37 | 0.71 | −2.20 |

| DS | 1.60 | 0.75 | 1.62 | 0.66 | 1.53 | 0.72 | 0.46 | −0.08 | 1.79 | 0.74 | 1.46 | 0.73 | 2.09 |

| E/p | 1.16 | 0.35 | 1.16 | 0.36 | 1.18 | 0.30 | −0.20 | −0.19 | 1.14 | 0.30 | 1.17 | 0.38 | −0.34 |

| D | 1.06 | 0.26 | 1.18 | 0.50 | 1.03 | 0.15 | −2.09 | −0.06 | 1.12 | 0.37 | 1.02 | 0.10 | 1.85 |

| SB/SH parents | 2.88 | 0.71 | 2.91 | 0.72 | 2.72 | 0.66 | 0.99 | −0.07 | 2.68 | 0.75 | 3.02 | 0.65 | −2.31 * |

| Peer attachment | 3.42 | 0.54 | 3.38 | 0.52 | 3.61 | 4.29 | −1.69 | 0.28 ** | 3.41 | 0.54 | 3.43 | 0.54 | −0.21 |

| β | SE | 95% CI | p | F(1,89) | R2 | adj R2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | LL | UL | ||||||

| Model 1 | 0.049 | 3.94 | 0.04 | 0.21 | ||||

| Constant | 5.60 *** | 1.08 | 3.45 | 7.75 | <0.001 | |||

| SB/SH parents | −0.72 * | 0.36 | −1.45 | 0.001 | 0.049 | |||

| Model 2 | 0.002 | 9.74 | 0.31 | 0.10 | ||||

| Constant | 8.77 *** | 1.70 | 5.39 | 12.15 | <0.001 | |||

| Peer attachment | −1.53 ** | 0.49 | −2.54 | −0.56 | 0.002 | |||

| Model 3 | 0.008 | 5.10 | 0.10 | 0.08 | ||||

| Intercept | 8.98 *** | 1.73 | 5.54 | 12.42 | <0.001 | |||

| SB/SH parents | −0.283 | 0.39 | −1.07 | 0.54 | 0.479 | |||

| Peer attachment | −1.36 * | 0.55 | −2.45 | −0.26 | 0.016 | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Muzi, S.; Rogier, G.; Pace, C.S. Peer Power! Secure Peer Attachment Mediates the Effect of Parental Attachment on Depressive Withdrawal of Teenagers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4068. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074068

Muzi S, Rogier G, Pace CS. Peer Power! Secure Peer Attachment Mediates the Effect of Parental Attachment on Depressive Withdrawal of Teenagers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(7):4068. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074068

Chicago/Turabian StyleMuzi, Stefania, Guyonne Rogier, and Cecilia Serena Pace. 2022. "Peer Power! Secure Peer Attachment Mediates the Effect of Parental Attachment on Depressive Withdrawal of Teenagers" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 7: 4068. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074068

APA StyleMuzi, S., Rogier, G., & Pace, C. S. (2022). Peer Power! Secure Peer Attachment Mediates the Effect of Parental Attachment on Depressive Withdrawal of Teenagers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(7), 4068. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074068