More Prosocial, More Ephemeral? The Role of Work-Related Wellbeing and Gender in Incubating Social Entrepreneurs’ Exit Intention

Abstract

1. Introduction

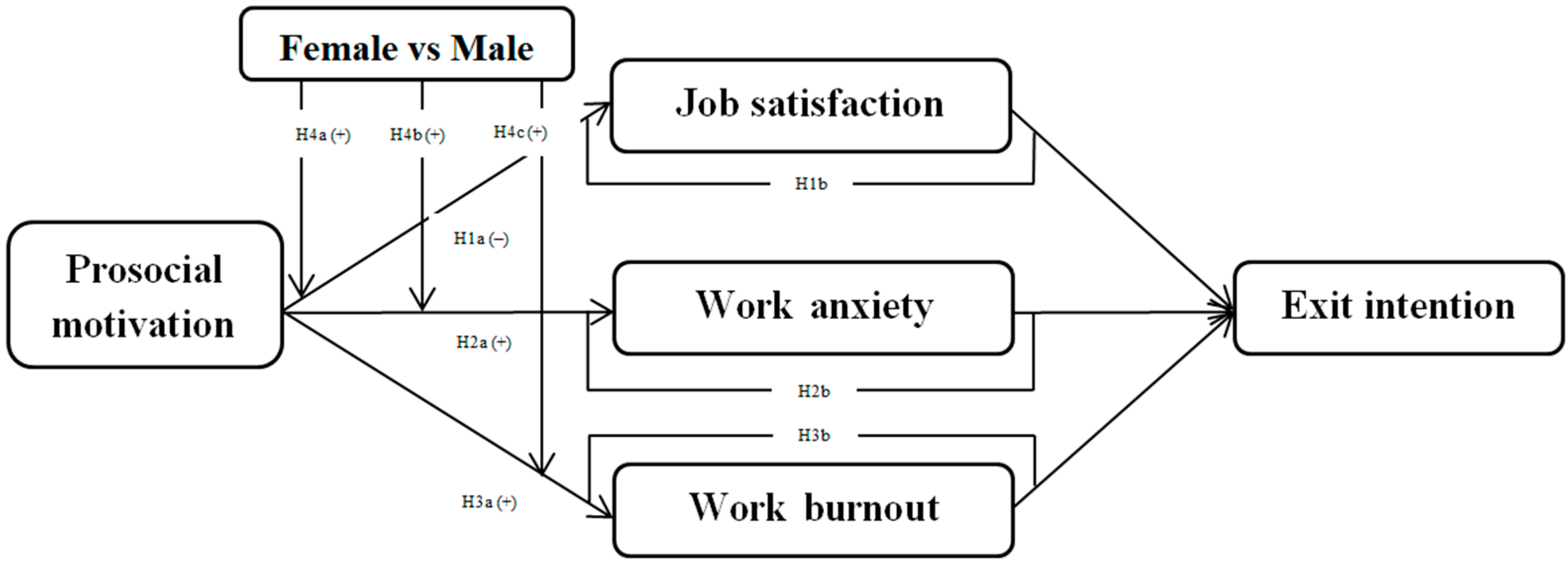

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Prosocial Motivation and Exit Intention

2.2. Work-Related Wellbeing

2.3. Prosocial Motivation, Job Satisfaction, and Exit Intention

2.4. Prosocial Motivation, Work Anxiety, and Exit Intention

2.5. Prosocial Motivation, Work Burnout, and Exit Intention

2.6. The Moderating Role of an Entrepreneur’s Gender

3. Method

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2. Variables and Measurement

3.3. Measurement of Control Variables

4. Data Analysis

4.1. Outer Model and Scale Validation

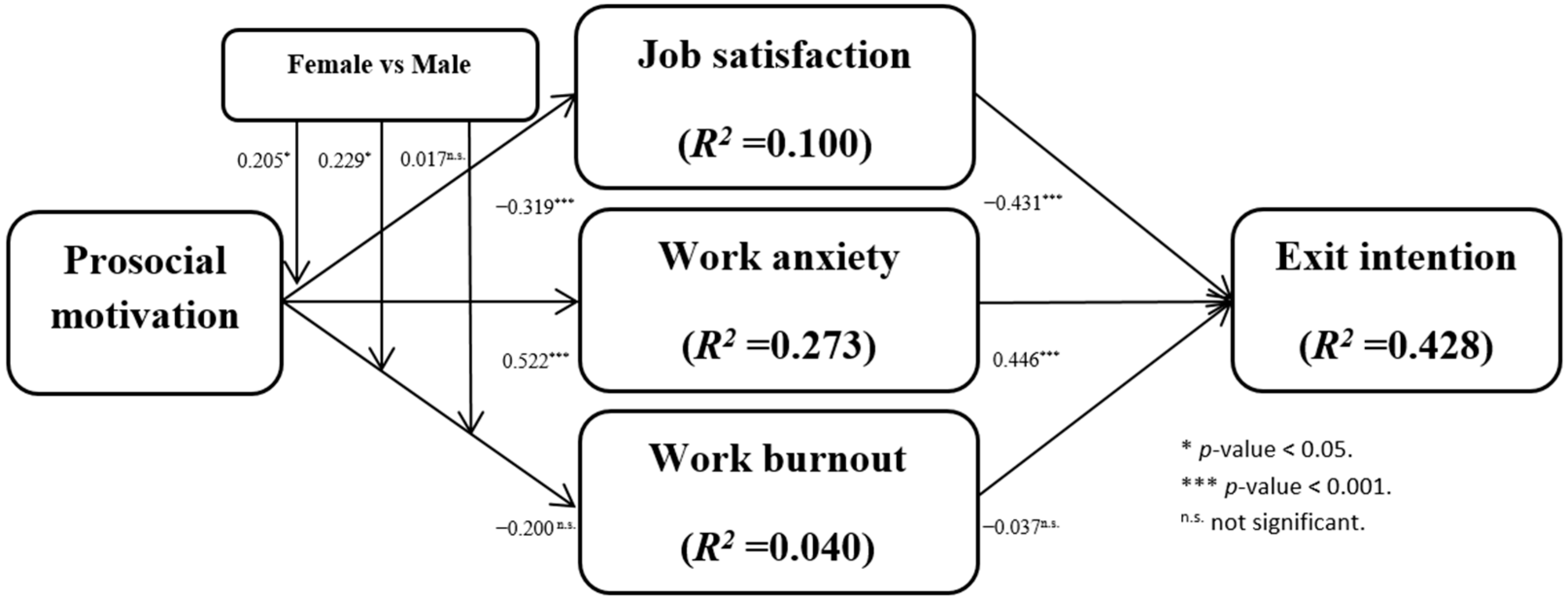

4.2. Inner Model and Hypotheses Testing

4.3. Testing of Mediation Effects

4.4. Multi-Group Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implication

5.2. Practical Implication

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Construct | Items | Variables | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prosocial Motivation (PM) |

| PM1-PM4 | [54] |

| |||

| |||

| |||

| Job Satisfaction (JS) |

| JS1 | [140] |

| Work Anxiety (WA) |

| WA1-WA4 | [145] |

| |||

| |||

| |||

| Work Burnout (WB) | When you think about your work overall, how often do you feel the following? | WB1-WB10 | [146] |

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

| Exit Intention (EI) | Participants rated the extent to which they would, in the next year? | EI1-EI3 | [49] |

| |||

| |||

|

References

- De Tienne, D.; Wennberg, K. Studying exit from entrepreneurship: New directions and insights. Int. Small Bus. J. 2016, 34, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hota, P.K. Tracing the Intellectual Evolution of Social Entrepreneurship Research: Past Advances, Current Trends, and Future Directions. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renko, M. Early Challenges of Nascent Social Entrepreneurs. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2013, 37, 1045–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacciotti, G.; Hayton, J.C.; Mitchell, J.R.; Allen, D.G. Entrepreneurial fear of failure: Scale development and validation. J. Bus. Ventur. 2020, 35, 106041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, H.E. Perpetually on the eve of destruction? Understanding exits in capitalist societies at multiple levels of analysis. Res. Handb. Entrep. Exit 2015, 11–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cefis, E.; Bettinelli, C.; Coad, A.; Marsili, O. Understanding firm exit: A systematic literature review. Small Bus. Econ. 2021, 56, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Wennberg, K.; Detienne, D.R. What do we really mean when we talk about ‘exit’? A critical review of research on entrepreneurial exit. Soc. Sci. Electron. Publ. 2014, 32, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socrates, K.; Gopalakrishna, B. Investigating the influence of psychological ownership on exit intention and passing-on option of Indian micro and small enterprise owners. Int. J. Indian Cult. Bus. Manag. 2021, 23, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardeshmukh, S.R.; Goldsby, M.; Smith, R.M. Are work stressors and emotional exhaustion driving exit intentions among business owners? J. Small Bus. Manag. 2021, 59, 544–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardon, M.S.; Foo, M.D.; Shepherd, D.; Wiklund, J. Exploring the Heart: Entrepreneurial Emotion Is a Hot Topic. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2012, 36, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tina, S.; Foss, N.J.; Stefan, L. Social Entrepreneurship Research: Past Achievements and Future Promises. J. Manag. 2018, 45, 70–95. [Google Scholar]

- Bolino, M.C.; Grant, A.M. The Bright Side of Being Prosocial at Work, and the Dark Side, Too: A Review and Agenda for Research on Other-Oriented Motives, Behavior, and Impact in Organizations. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2016, 10, 599–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brieger, S.A.; Terjesen, S.A.; Hechavarría, D.M.; Welzel, C. Prosociality in Business: A Human Empowerment Framework. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 159, 361–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brieger, S.; Clercq, D.D.; Meynhardt, T. Doing Good, Feeling Good? Entrepreneurs’ Social Value Creation Beliefs and Work-Related Well-Being. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 172, 707–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korsgaard, S.; Anderson, A.R. Enacting entrepreneurship as social value creation. Int. Small Bus. J. Res. Entrep. 2011, 29, 135–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroeger, A.; Weber, C. Developing a Conceptual Framework for Comparing Social Value Creation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2014, 39, 513–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, F.M. A Positive Theory of Social Entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 111, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, T.L.; Grimes, M.G.; Mcmullen, J.S.; Vogus, T.J. Venturing for Others with Heart and Head: How Compassion Encourages Social Entrepreneurship. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2012, 37, 616–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranville, A.; Barros, M. Towards Normative Theories of Social Entrepreneurship. A Review of the Top Publications of the Field. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibler, E.; Wincent, J.; Kautonen, T.; Cacciotti, G.; Obschonka, M. Can Prosocial Motivation Harm Entrepreneurs’ Subjective Well-being? J. Bus. Ventur. 2019, 34, 608–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brieger, S.A.; De Clercq, D. Entrepreneurs’ individual-level resources and social value creation goals: The moderating role of cultural context. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2019, 25, 1355–2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin, S.; Nathalie, M.; Johan, B. The Social and Economic Mission of Social Enterprises: Dimensions, Measurement, Validation, and Relation. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2015, 39, 1051–1082. [Google Scholar]

- Wennberg, K.; Wiklunc, J.; Detienne, D.R.; Cardon, M.S. Reconceptualizing Entrepreneurial Exit: Divergent Exit Routes and Their Drivers. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 361–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M. Relational Job Design and the Motivation to Make a Prosocial Difference. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 393–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcmullen, J.S.; Bergman, B. Social Entrepreneurship and the Development Paradox of Prosocial Motivation: A Cautionary Tale. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2017, 11, 243–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, N.; Guthrie, I.K.; Cumberland, A.; Murphy, B.C.; Shepard, S.A.; Zhou, Q.; Carlo, G. Prosocial development in early adulthood: A longitudinal study. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 82, 993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauch, A.; Frese, M. Psychological approaches to entrepreneurial success: A general model and an overview of findings. Int. Rev. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2000, 15, 101–142. [Google Scholar]

- Rauch, A.; Frese, M. Let’s put the person back into entrepreneurship research: A meta-analysis on the relationship between business owners’ personality traits, business creation, and success: European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2007, 16, 353–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frese, M. The Psychology of Entrepreneurship. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2014, 1, 413–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, J.R.; Frese, M.; Baron, R.A. Born to be an entrepreneur? Revisiting the personality approach to entrepreneurship. In The Psychology of Entrepreneurship; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 73–98. [Google Scholar]

- Lindblom, A.; Lindblom, T.; Wechtler, H. Dispositional optimism, entrepreneurial success and exit intentions: The mediating effects of life satisfaction. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 120, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allport, G.W. Pattern and Growth in Personality; Holt, Reinhart & Winston: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck, H.J. Dimensions of Personality. In Explorations in Temperament: International Perspectives on Theory and Measurement; Strelau, J., Angleitner, A., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1991; pp. 87–103. [Google Scholar]

- Judge, T.A.; Larsen, R. Dispositional Affect and Job Satisfaction: A Review and Theoretical Extension. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2001, 86, 67–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaev, B.; Shir, N.; Wiklund, J. Dispositional Positive and Negative Affect and Self-Employment Transitions: The Mediating Role of Job Satisfaction. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2019, 44, 451–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, R.P. Turnover theory at the empirical interface: Problems of fit and function. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 346–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boswell, W.R.; Boudreau, J.W.; Tichy, J. The relationship between employee job change and job satisfaction: The honeymoon-hangover effect. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 882–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, J.J.; Schaufeli, W.B. Do burnout and work engagement predict depressive symptoms and life satisfaction? A three-wave seven-year prospective study. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 141, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Salanova, M.; González-romá, V.; Bakker, A.B. The Measurement of Engagement and Burnout: A Two Sample Confirmatory Factor Analytic Approach. J. Happiness Stud. 2002, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GEM. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. Soc. Sci. Electron. Publ. 2011, 3, 66–70. [Google Scholar]

- Wry, T.; York, J.G. An identity-based approach to social enterprise. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2017, 42, 437–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koellinger, P.; Minniti, M.; Schade, C. Gender differences in entrepreneurial propensity. Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat. 2013, 75, 213–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickel, P.; Eckardt, G. Who wants to be a social entrepreneur? The role of gender and sustainability orientation. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2021, 59, 196–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lortie, J.; Castrogiovanni, G.J.; Cox, K.C. Gender, social salience, and social performance: How women pursue and perform in social ventures. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2017, 29, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.K.; Wieland, A.M.; Turban, D.B. Gender characterizations in entrepreneurship: A multi-level investigation of sex-role stereotypes about high-growth, commercial, and social entrepreneurs. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2019, 57, 131–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dacin, M.T.; Dacin, P.A.; Tracey, P. Social Entrepreneurship: A Critique and Future Directions. Organ. Sci. 2011, 22, 1203–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.-M. SmartPLS 3. SmartPLS GmbH, Boenningstedt. J. Serv. Sci. Manag. 2015, 10, 32–49. [Google Scholar]

- Light, P.C. Reshaping social entrepreneurship. Stanf. Soc. Innov. Rev. 2006, 4, 47–51. [Google Scholar]

- Pollack, J.M.; Vanepps, E.M.; Hayes, A.F. The moderating role of social ties on entrepreneurs’ depressed affect and withdrawal intentions in response to economic stress. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 789–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, K. Social Entrepreneurs and Their Personality. In Social Entrepreneurship and Social Business; Gabler Verlag: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2012; pp. 51–64. [Google Scholar]

- Penner, L.A.; Finkelstein, M.A. Dispositional and Structural Determinants of Volunteerism. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 74, 525–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Attitudes, Traits, and Actions: Dispositional Prediction of Behavior in Personality and Social Psychology. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Berkowitz, L., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1987; Volume 20, pp. 1–63. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, D.A.; Newman, D.A.; Roth, P.L. How Important are Job Attitudes? Meta-Analytic Comparisons of Integrative Behavioral Outcomes and Time Sequences. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 305–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A. Does Intrinsic Motivation Fuel the Prosocial Fire? Motivational Synergy in Predicting Persistence, Performance, and Productivity. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mair, J.; Noboa, E. Social entrepreneurship: How intentions to create a social venture are formed. In Social Entrepreneurship; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 121–135. [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers, D. Social Entrepreneurship’s Solutionism Problem. J. Manag. Stud. 2021, 58, 1363–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz, P.; Cacciotti, G. Understanding failure and exit in social entrepreneurship: A protocol analysis of coping strategies. In Proceedings of the Babson College Entrepreneurship Research Conference, London, ON, Canada, 4–7 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dorado, S. Social entrepreneurial ventures: Different values so different process of creation, no? J. Dev. Entrep. 2006, 11, 319–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purdue; Derrick. Neighbourhood Governance: Leadership, Trust and Social Capital. Urban Stud. 2001, 38, 2211–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, S.M. Gauging the success of social ventures initiated by individual social entrepreneurs. J. World Bus. 2006, 41, 6–20. [Google Scholar]

- Zahra, S.A.; Gedajlovic, E.; Neubaum, D.O.; Shulman, J.M. A typology of social entrepreneurs: Motives, search processes and ethical challenges. J. Bus. Ventur. 2009, 24, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, D.; Wiklund, J.; Haynie, J.M. Moving forward: Balancing the financial and emotional costs of business failure. J. Bus. Ventur. 2009, 24, 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, A.S.; Wiklund, J.; Brundin, E. Individual responses to firm failure: Appraisals, grief, and the influence of prior failure experience. J. Bus. Ventur. 2014, 29, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessels, J.; Rietveld, C.A.; Thurik, A.R.; Peter, V.D.Z. Depression and entrepreneurial exit. Acad. Manag. Exec. 2018, 32, 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caliendo, M.; Fossen, F.; Kritikos, A.S. Personality characteristics and the decisions to become and stay self-employed. Small Bus. Econ. 2014, 42, 787–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.L.; Madole, J.W.; Freeman, M.A. Mania risk and entrepreneurship: Overlapping personality traits. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 32, 207–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, U. Entrepreneurs’ Mental Health and Well-Being: A Review and Research Agenda. Acad. Manag. Exec. 2018, 32, 290–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, H.M. Deconstructing job satisfaction: Separating evaluations, beliefs and affective experiences. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2003, 12, 173–194. [Google Scholar]

- Orsila, R.; Luukkaala, T.; Manka, M.L.; Nygard, C.H.K. A New Approach to Measuring Work-Related Well-Being. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2011, 17, 341–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Diener, E. Subjective well-being. The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasamar, S.; Alegre, J. Adoption and use of work-life initiatives: Looking at the influence of institutional pressures and gender. Eur. Manag. J. 2015, 33, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagán-Castao, E.; Maseda-Moreno, A.; Santos-Rojo, C. Wellbeing in work environments. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 115, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westhuizen, S.V.D. Work Related Well-Being: Burnout, Work Engagement, Occupational Stress and Job Satisfaction Within a Medical Laboratory Setting. J. Psychol. Afr. 2013, 23, 467–474. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, K.; Munir, F. How do transformational leaders influence followers’ affective well-being? Exploring the mediating role of self-efficacy. Work. Stress 2009, 23, 313–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuyper, N.D.; Elst, T.V.; Broeck, A.V.D.; Witte, H.D. The mediating role of frustration of psychological needs in the relationship between job insecurity and work-related well-being. Work Stress 2012, 26, 252–271. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, T.A. The emergence of job satisfaction in organizational behavior: A historical overview of the dawn of job attitude research. J. Manag. Hist. 2006, 12, 262–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warr, P. Work, Happiness, and Unhappiness; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 1–548. [Google Scholar]

- Warr, P. The Study of Well-being, Behaviour and Attitudes. In Psychology at Work, 5th ed.; Penguin Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ilies, R.; Wilson, K.S.; Wagner, D.T. The Spillover of Daily Job Satisfaction onto Employees’ Family Lives: The Facilitating Role of Work-Family Integration. Acad. Manag. J. 2009, 52, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steijn, B.; van der Voet, J. Relational job characteristics and job satisfaction of public sector employees: When prosocial motivation and red tape collide. Public Adm. 2019, 97, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjeldsen, A.M.; Andersen, L.B. How Pro-social Motivation Affects Job Satisfaction: An International Analysis of Countries with Different Welfare State Regimes. Scand. Political Stud. 2013, 36, 153–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, D.A. Party On! A call for entrepreneurship research that is more interactive, activity based, cognitively hot, compassionate, and prosocial. J. Bus. Ventur. 2015, 30, 489–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolino, M.C.; Turnley, W.H. The personal costs of citizenship behavior: The relationship between individual initiative and role overload, job stress, and work-family conflict. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, M.; Niemiec Christopher, P.; Soenens, B. The development of the five mini-theories of self-determination theory: An historical overview, emerging trends, and future directions. In The Decade Ahead: Theoretical Perspectives on Motivation and Achievement; Timothy, C.U., Stuart, A.K., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2010; Volume 16, Part A, pp. 105–165. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hiel, A.; Vansteenkiste, M. Ambitions Fulfilled? The Effects of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Goal Attainment on Older Adults’ Ego-Integrity and Death Attitudes. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2009, 68, 27–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broeck, A.V.D.; Ferris, D.L.; Chang, C.H.; Rosen, C.C. A Review of Self-Determination Theorys Basic Psychological Needs at Work. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 1195–1229. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Huta, V.; Deci, E.L. Living well: A self-determination theory perspective on eudaimonia. J. Happiness Stud. 2008, 9, 139–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge; Weiss, H.M.; Kammeyer-Mueller, J.D.; Hulin, C.L. Job attitudes, job satisfaction, and job affect: A century of continuity and of change. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 356–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaumberg, R.L.; Flynn, F.J. Clarifying the link between job satisfaction and absenteeism: The role of guilt proneness. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 982–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhan, Y.; Liu, S.; Shultz, K.S. Antecedents of bridge employment: A longitudinal investigation. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 818–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, S.; Godkin, L.; Fleischman, G.M.; Kidwell, R. Corporate Ethical Values, Group Creativity, Job Satisfaction and Turnover Intention: The Impact of Work Context on Work Response. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 98, 353–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M. Leading with meaning: Beneficiary contact, prosocial impact, and the performance effects of transformational leadership. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 458–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M.; Sumanth, J.J. Mission possible? The performance of prosocially motivated employees depends on manager trustworthiness. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 927–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spector, P.E.; Dwyer, D.J.; Jex, S.M. Relation of job stressors to affective, health, and performance outcomes: A comparison of multiple data sources. J. Appl. Psychol. 1988, 73, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spielberger, C.D. Anxiety and Behavior; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Hoogendoorn, B.; Zwan, P.V.D.; Thurik, R. Sustainable Entrepreneurship: The Role of Perceived Barriers and Risk. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 157, 1133–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beutell, N.J.; Alstete, J.W.; Schneer, J.A.; Hutt, C. A look at the dynamics of personal growth and self-employment exit. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2019, 25, 1452–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñeiro-Chousa, J.; López-Cabarcos, M.Á.; Romero-Castro, N.M.; Pérez-Pico, A.M. Innovation, entrepreneurship and knowledge in the business scientific field: Mapping the research front. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 115, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.; Obschonka, M.; Block, J. Small Businesses and Entrepreneurship in Times of Crises: The Renaissance of Entrepreneur-Focused Micro Perspectives. Int. Small Bus. J. 2022, 40, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, S.; Kundi, Y.M. Feel dragged out: A recovery perspective in the relationship between emotional exhaustion and entrepreneurial exit. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrick, D.C.; Finkelstein, S.; Mooney, A.C. Executive Job Demands: New Insights for Explaining Strategic Decisions and Leader Behaviors. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2005, 30, 472–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vries, M. Putting leaders on the couch. A conversation with Manfred F. R. Kets de Vries. Interview by Diane L. Coutu. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2004, 82, 64–71, 113. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, N.A.; Gelderen, M.V.; Keppler, L. No Need to Worry? Anxiety and Coping in the Entrepreneurship Process. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowe, R.P.; Bower, J.K.; Cash, R.E.; Panchal, A.R.; Rodriguez, S.A.; Olivo-Marston, S.E. Association of Burnout with Workforce-Reducing Factors among EMS Professionals. Prehospital Emerg. Care 2018, 22, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-P.; Lee, D.-C.; Wang, H.-H. Violence-prevention climate in the turnover intention of nurses experiencing workplace violence and work frustration. J. Nurs. Manag. 2018, 26, 961–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, J.M.; Patel, P.C.; Messersmith, J.G. High-Performance Work Systems and Job Control: Consequences for Anxiety, Role Overload, and Turnover Intentions. J. Manag. 2011, 39, 1699–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Høigaard, R.; Giske, R.; Sundsli, K. Newly qualified teachers’ work engagement and teacher efficacy influences on job satisfaction, burnout, and the intention to quit. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2012, 35, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Du, N.; Zhang, X. When an interfirm relationship is ending: The dark side of managerial ties and relationship intimacy. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 125, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Sixma, H.J.; Bosveld, W. Burnout Contagion Among General Practitioners. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2001, 20, 82–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and work motivation. J. Organ. Behav. 2010, 26, 331–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuer, A.T.K.; Van Dijk, G.; Jongerden, J. Exit strategies for social venture entrepreneurs in sub-Sahara Africa: A literature review. Afr. J. Manag. 2021, 7, 509–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Vohs, K.D.; Tice, D.M. The Strength Model of Self-Control. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 16, 351–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tice, D.M.; Baumeister, R.; Shmueli, D.; Muraven, M. Restoring the self: Positive affect helps improve self-regulation following ego depletion. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 43, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimakwa, S.; Gonzalez, J.A.; Kaynak, H. Social Entrepreneur Servant Leadership and Social Venture Performance: How are They Related? J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandey, A.A.; Sin, D.H.P. The Customer is Not Always Right: Customer Aggression and Emotion Regulation of Service Employees. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 397–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swider, B.W.; Zimmerman, R.D. Born to burnout: A meta-analytic path model of personality, job burnout, and work outcomes. J. Vocat. Behav. 2010, 76, 487–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P. Job Burnout. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A. Sex Differences in Social Behavior: A Social-Role Interpretation; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 1987; pp. 1–192. [Google Scholar]

- Heilman, M.E. Sex bias in work settings: The lack of fit model. Res. Organ. Behav. 1983, 5, 269–298. [Google Scholar]

- Heilman, M.E. Description and prescription: How gender stereotypes prevent women’s ascent up the organizational ladder. J. Soc. Issues 2001, 57, 657–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacq, S.; Alt, E. Feeling capable and valued: A prosocial perspective on the link between empathy and social entrepreneurial intentions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2018, 33, 333–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BarNir, A.; Watson, W.E.; Hutchins, H.M. Mediation and moderated mediation in the relationship among role models, self-efficacy, entrepreneurial career intention, and gender. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 41, 270–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.K.; Turban, D.B.; Wasti, S.A.; Sikdar, A. The role of gender stereotypes in perceptions of entrepreneurs and intentions to become an entrepreneur. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 397–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madera, J.M.; King, E.B.; Hebl, M.R. Bringing social identity to work: The influence of manifestation and suppression on perceived discrimination, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minority Psychol. 2012, 18, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, W.M.; Schmader, T.; Croft, E. Engineering exchanges: Daily social identity threat predicts burnout among female engineers. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2015, 6, 528–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, J.W. Linking Stereotype Threat and Anxiety. Educ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 135–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberson, L.; Kulik, C.T. Stereotype threat at work. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2007, 21, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimbu, A.N.; Ngoasong, M.Z. Women as vectors of social entrepreneurship. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 60, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayawarna, D.; Marlow, S.; Swail, J. A Gendered Life Course Explanation of the Exit Decision in the Context of Household Dynamics. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2021, 45, 1394–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, R.S. Conceptualizing the International For-Profit Social Entrepreneur. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 98, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justo, R.; DeTienne, D.R.; Sieger, P. Failure or voluntary exit? Reassessing the female underperformance hypothesis. J. Bus. Ventur. 2015, 30, 775–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, G.N.; Eddleston, K.A. Linking family-to-business enrichment and support to entrepreneurial success: Do female and male entrepreneurs experience different outcomes? J. Bus. Ventur. 2013, 28, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, B.; Haugh, H.; Lyon, F. Social Enterprises as Hybrid Organizations: A Review and Research Agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2014, 16, 417–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. In Handbook of Cross-Cultural Psychology: Methodology; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1980; pp. 389–444. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory 3E; Tata McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kropp, F.; Lindsay, N.J.; Shoham, A. Entrepreneurial orientation and international entrepreneurial business venture startup. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2008, 14, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepoutre, J.; Justo, R.; Terjesen, S.; Bosma, N. Designing a global standardized methodology for measuring social entrepreneurship activity: The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor social entrepreneurship study. Small Bus. Econ. 2013, 40, 693–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, U.; Uhlaner, L.M.; Stride, C. Institutions and social entrepreneurship: The role of institutional voids, institutional support, and institutional configurations. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2015, 46, 308–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrin, S.; Mickiewicz, T.; Stephan, U. Entrepreneurship, social capital, and institutions: Social and commercial entrepreneurship across nations. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2013, 37, 479–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chordiya, R.; Sabharwal, M.; Goodman, D. Affective organizational commitment and job satisfaction: A cross-national comparative study. Public Adm. 2017, 95, 178–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moynihan, D.P.; Pandey, S.K. Finding workable levers over work motivation: Comparing job satisfaction, job involvement, and organizational commitment. Adm. Soc. 2007, 39, 803–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-J.; Sabharwal, M. Education–job match, salary, and job satisfaction across the public, non-profit, and for-profit sectors: Survey of recent college graduates. Public Manag. Rev. 2016, 18, 40–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpello, V.; Campbell, J.P. Job satisfaction: Are all the parts there? Pers. Psychol. 1983, 36, 577–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanous, J.P.; Reichers, A.E.; Hudy, M.J. Overall job satisfaction: How good are single-item measures? J. Appl. Psychol. 1997, 82, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haider, S.; Fatima, N.; Pablos-Heredero, C.D. A Three-Wave Longitudinal Study of Moderated Mediation between Perceptions of Politics and Employee Turnover Intentions: The Role of Job Anxiety and Political Skills. Rev. Psicol. Trab. Organ. 2020, 36, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malach-Pines, A. The Burnout Measure, Short Version. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2005, 12, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Wang, S. How does the age of serial entrepreneurs influence their re-venture speed after a business failure? Small Bus. Econ. 2019, 52, 651–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayr, U.; Freund, A.M. Do we become more prosocial as we age, and if so, why? Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 29, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, R. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor: United Kingdom 2004. Soc. Sci. Electron. Publ. 2006, 3, 66–70. [Google Scholar]

- Manley, S.C.; Hair, J.F.; Williams, R.I.; McDowell, W.C. Essential new PLS-SEM analysis methods for your entrepreneurship analytical toolbox. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2021, 17, 1805–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 1998, 295, 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W.; Newsted, P.R. Structural equation modeling analysis with small samples using partial least squares. Stat. Strateg. Small Sample Res. 1999, 1, 307–341. [Google Scholar]

- Gefen, D.; Rigdon, E.E.; Straub, D. Editor’s comments: An update and extension to SEM guidelines for administrative and social science research. Mis Q. 2011, 35, iii–xiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majchrzak, A.; Malhotra, A.; John, R. Perceived individual collaboration know-how development through information technology–enabled contextualization: Evidence from distributed teams. Inf. Syst. Res. 2005, 16, 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Organ, D.W. Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. J. Manag. 1986, 12, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, A.H.; Malhotra, A.; Segars, A.H. Knowledge management: An organizational capabilities perspective. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2001, 18, 185–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Southend Oaks, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.; Hallak, R. Investigating the moderating role of education on a structural model of restaurant performance using multi-group PLS-SEM analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 88, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling; Sage Publications: Southend Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Detienne, D.R. Entrepreneurial exit as a critical component of the entrepreneurial process: Theoretical development. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, E.W.; Shapard, L. Employee Burnout: A Meta-Analysis of the Relationship Between Age or Years of Experience. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2004, 3, 102–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchand, A.; Blanc, M.-E.; Beauregard, N. Do age and gender contribute to workers’ burnout symptoms? Occup. Med. 2018, 68, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahola, K.; Honkonen, T.; Isometsä, E.; Kalimo, R.; Nykyri, E.; Koskinen, S.; Aromaa, A.; Lönnqvist, J. Burnout in the general population. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2006, 41, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.C. The Economics of Entrepreneurship; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Diekman, A.B.; Clark, E.K. Beyond the damsel in distress: Gender differences and similarities in enacting prosocial behavior. Oxf. Handb. Prosocial Behav. 2015, 12, 376–391. [Google Scholar]

- Judge, T.A.; Livingston, B.A.; Hurst, C. Do nice guys—And gals—Really finish last? The joint effects of sex and agreeableness on income. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 102, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carree, M.A.; Verheul, I. What makes entrepreneurs happy? Determinants of satisfaction among founders. J. Happiness Stud. 2012, 13, 371–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Watanabe, S. Another look at the job satisfaction-life satisfaction relationship. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacq, S.; Janssen, F. The multiple faces of social entrepreneurship: A review of definitional issues based on geographical and thematic criteria: Entrepreneurship & Regional Development. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2011, 23, 373–403. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, K.; Newbert, S.; Quigley, N. The motivational drivers underlying for-profit venture creation: Comparing social and commercial entrepreneurs. Int. Small Bus. J. Res. Entrep. 2017, 36, 220–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Frequency | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 18–25 | 19 | 6.30% |

| 26–35 | 105 | 34.90% |

| 36–45 | 118 | 39.20% |

| 46–55 | 59 | 19.60% |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 145 | 48.20% |

| Female | 156 | 51.80% |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 202 | 67.10% |

| Non-married | 99 | 32.90% |

| Educational Level | ||

| Junior high school | 0 | 0% |

| High school or equal | 3 | 1% |

| Junior college | 75 | 24.90% |

| Bachelor degree | 127 | 42.20% |

| Postgraduate or above | 96 | 31.90% |

| Construct | Items | Factor Loading | α | Rho_A | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prosocial Motivation (PM) | PM 1 | 0.865 | 0.844 | 0.849 | 0.895 | 0.682 |

| PM 2 | 0.845 | - | - | - | - | |

| PM 3 | 0.75 | - | - | - | - | |

| PM 4 | 0.841 | - | - | - | - | |

| Work Burnout (WB) | WB 1 | 0.585 | 0.967 | 0.844 | 0.949 | 0.657 |

| WB 2 | 0.555 | - | - | - | - | |

| WB 3 | 0.646 | - | - | - | - | |

| WB 4 | 0.735 | - | - | - | - | |

| WB 5 | 0.9 | - | - | - | - | |

| WB 6 | 0.946 | - | - | - | - | |

| WB 7 | 0.835 | - | - | - | - | |

| WB 8 | 0.94 | - | - | - | - | |

| WB 9 | 0.944 | - | - | - | - | |

| WB 10 | 0.887 | - | - | - | - | |

| Work Anxiety (WA) | WA 1 | 0.889 | 0.922 | 0.951 | 0.944 | 0.808 |

| WA 2 | 0.926 | - | - | - | - | |

| WA 3 | 0.904 | - | - | - | - | |

| WA 4 | 0.875 | - | - | - | - | |

| Job Satisfaction (JS) | JS 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Exit Intention (EI) | EI 1 | 0.902 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.955 | 0.877 |

| EI 2 | 0.963 | - | - | - | - | |

| EI 3 | 0.944 | - | - | - | - |

| Constructs | EI | JS | PM | WA | WB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EI | |||||

| JS | 0.499 | ||||

| PM | 0.558 | 0.348 | |||

| WA | 0.505 | 0.101 | 0.575 | ||

| WB | 0.053 | 0.075 | 0.136 | 0.079 |

| Items | EI | JS | PM | WA | WB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EI1 | 0.901 | −0.504 | 0.433 | 0.389 | −0.081 |

| EI2 | 0.963 | −0.470 | 0.468 | 0.474 | −0.062 |

| EI3 | 0.944 | −0.402 | 0.481 | 0.517 | −0.049 |

| JS1 | −0.489 | 1 | −0.316 | −0.105 | 0.082 |

| PM1 | 0.437 | −0.234 | 0.867 | 0.435 | −0.283 |

| PM2 | 0.351 | −0.221 | 0.847 | 0.472 | −0.101 |

| PM3 | 0.379 | −0.292 | 0.746 | 0.367 | −0.074 |

| PM4 | 0.456 | −0.301 | 0.842 | 0.448 | −0.185 |

| WA1 | 0.318 | −0.017 | 0.381 | 0.89 | 0.023 |

| WA2 | 0.409 | −0.116 | 0.467 | 0.927 | −0.048 |

| WA3 | 0.378 | −0.086 | 0.432 | 0.904 | 0.026 |

| WA4 | 0.588 | −0.156 | 0.552 | 0.875 | 0.014 |

| WB1 | 0.03 | 0.004 | 0.01 | 0.038 | 0.585 |

| WB10 | −0.009 | 0.059 | −0.121 | 0.075 | 0.883 |

| WB2 | 0.042 | 0.062 | 0.086 | 0.107 | 0.552 |

| WB3 | 0.086 | 0.025 | 0.054 | 0.148 | 0.643 |

| WB4 | 0.016 | 0.048 | −0.048 | 0.053 | 0.732 |

| WB5 | −0.049 | 0.018 | −0.142 | −0.011 | 0.902 |

| WB6 | −0.045 | 0.075 | −0.106 | 0.038 | 0.945 |

| WB7 | −0.033 | 0.065 | −0.085 | 0.058 | 0.833 |

| WB8 | −0.049 | 0.067 | −0.161 | 0.038 | 0.94 |

| WB9 | −0.056 | 0.053 | −0.199 | −0.002 | 0.944 |

| Hypotheses | Path Coefficients (β) | t-Value | Supported |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1a: PM→JS | −0.319 *** | 6.33 | Yes |

| H2a: PM→WA | 0.522 *** | 8.825 | Yes |

| H3a: PM→WB | −0.200 n.s. | 1.318 | No |

| Hypotheses | Path | Direct | Indirect | Total | VAF | Mediation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1b | PM→JS→EI | 0.177 n.s. | 0.133 *** | 0.31 | 42.90% | Supported |

| (−0.532) | (−4.958) | |||||

| H2b | PM→WA→EI | 0.177 n.s. | 0.183 *** | 0.36 | 50.80% | Supported |

| (−0.532) | (−4.133) | |||||

| H3b | PM→WB→EI | 0.177 n.s. | 0.003 n.s. | 0.18 | 16.70% | Not Supported |

| (−0.532) | (−0.311) |

| Hypotheses | Path | Pooled N = 301 | Group A (Male) | Group B (Female) | Grp A vs. Grp B | Supported | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 145 | N = 156 | ||||||||

| β | CI | β | CI | β | CI | p-Value | |||

| H4a | PM→JS | −0.334 | (−0.421, −0.236) | −0.177 | (−0.330, −0.034) | −0.391 | (−0.518, −0.251) | 0.046 | Yes |

| H4b | PM→WA | 0.522 | (0.407, 0.626) | 0.624 | (0.481, 0.729) | 0.395 | (0.182, 0.551) | 0.044 | Yes |

| H4c | PM→WB | −0.200 | (−0.316, 0.331) | −0.231 | (−0.341, 0.390) | −0.247 | (−0.465, −0.140) | 0.87 | No |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dong, J.; Wang, X.; Cao, X.; Higgins, D. More Prosocial, More Ephemeral? The Role of Work-Related Wellbeing and Gender in Incubating Social Entrepreneurs’ Exit Intention. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3999. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19073999

Dong J, Wang X, Cao X, Higgins D. More Prosocial, More Ephemeral? The Role of Work-Related Wellbeing and Gender in Incubating Social Entrepreneurs’ Exit Intention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(7):3999. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19073999

Chicago/Turabian StyleDong, Jianing, Xiao Wang, Xuanwei Cao, and David Higgins. 2022. "More Prosocial, More Ephemeral? The Role of Work-Related Wellbeing and Gender in Incubating Social Entrepreneurs’ Exit Intention" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 7: 3999. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19073999

APA StyleDong, J., Wang, X., Cao, X., & Higgins, D. (2022). More Prosocial, More Ephemeral? The Role of Work-Related Wellbeing and Gender in Incubating Social Entrepreneurs’ Exit Intention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(7), 3999. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19073999