Do the Determinants of Mental Wellbeing Vary by Housing Tenure Status? Secondary Analysis of a 2017 Cross-Sectional Residents Survey in Cornwall, South West England

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Summary of Current Research

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Context

3.2. Resident Survey

- About your local area and Cornwall Council;

- Contacting the Council;

- Community Safety;

- Respect and consideration;

- Your home;

- Helping out (volunteering);

- Any other comments;

- Council newsletter (an opportunity to sign up for this);

- About you (socio-demographics).

3.3. Statistical Analysis

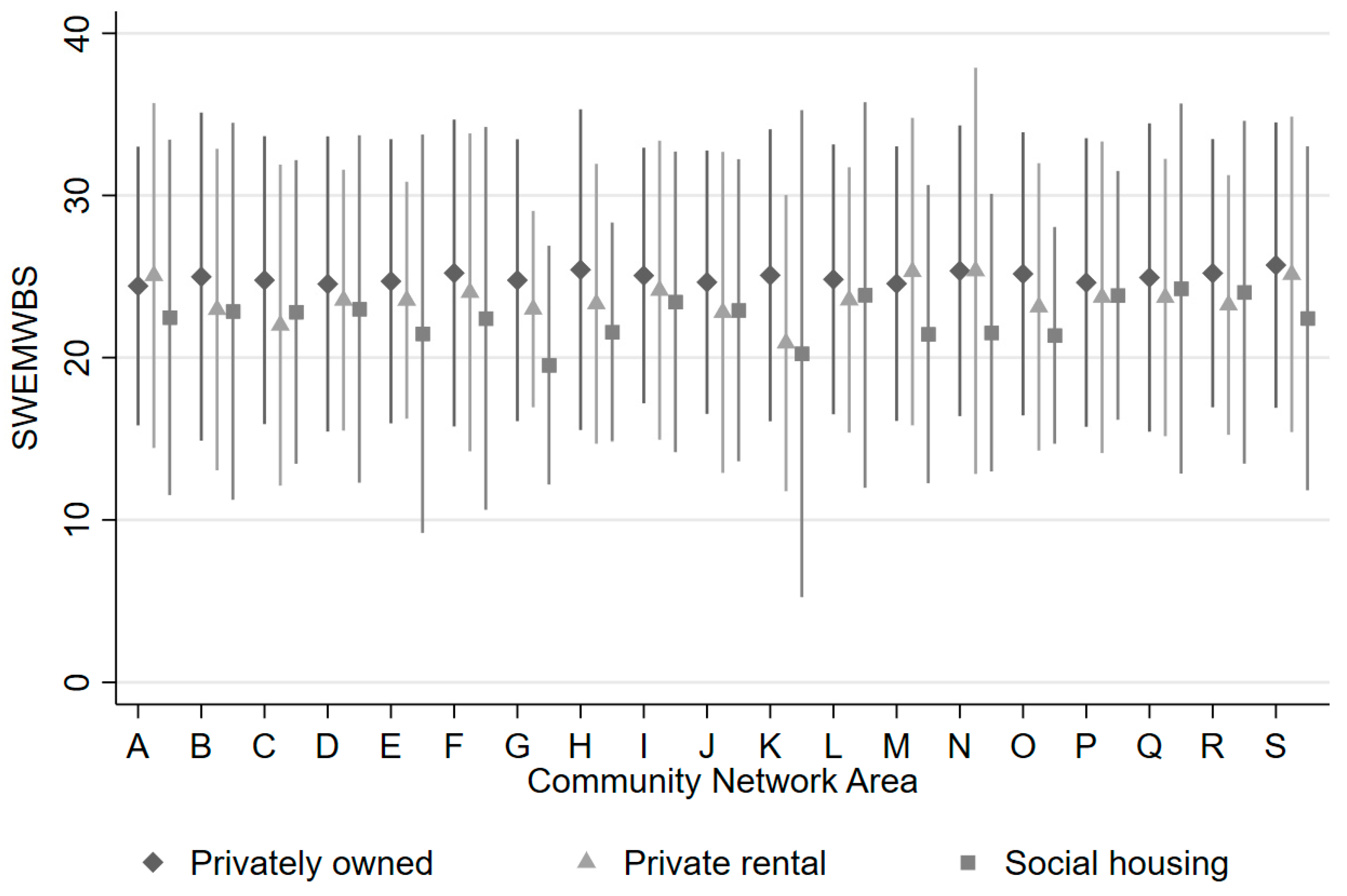

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| All | Privately Owned | Private Rental | Social Housing | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual Circumstances | n = 4085 | n = 3218 | n = 518 | n = 349 | |

| IC1. Age group | 16–17 y | 1.7% | 1.8% | 1.0% | 1.4% |

| 18–24 y | 3.6% | 2.8% | 7.5% | 5.2% | |

| 25–34 y | 8.7% | 6.2% | 20.7% | 14.3% | |

| 35–44 y | 12.9% | 11.3% | 21.6% | 14.3% | |

| 45–54 y | 19.3% | 19.2% | 18.5% | 20.9% | |

| 55–64 y | 22.5% | 23.8% | 16.0% | 20.3% | |

| 65–74 y | 22.2% | 24.7% | 11.6% | 15.5% | |

| 75–84 y | 7.4% | 8.2% | 2.5% | 7.2% | |

| 85+ y | 1.7% | 2.0% | 0.6% | 0.9% | |

| IC2. Gender | Female | 52.3% | 50.6% | 57.3% | 61.0% |

| Male | 47.7% | 49.4% | 42.7% | 39.0% | |

| IC3. Ethnicity | White | 98.9% | 99.2% | 98.5% | 97.1% |

| Other | 1.1% | 0.8% | 1.5% | 2.9% | |

| IC4. Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (SWEMWBS) score | 24.56 ± 4.64 | 24.94 ± 4.49 | 23.50 ± 4.64 | 22.58 ± 5.16 | |

| IC5. How is your health in general? | Very bad | 1.1% | 0.8% | 1.0% | 4.6% |

| Bad | 4.7% | 3.0% | 7.9% | 15.8% | |

| Fair | 19.2% | 18.3% | 16.2% | 32.1% | |

| Good | 45.4% | 47.5% | 43.1% | 29.8% | |

| Very good | 29.5% | 30.4% | 31.9% | 17.8% | |

| IC6. Are your day-to-day activities limited because of a health problem or disability that has lasted, or is expected to last, at least 12 months (including problems related to old age)? | No | 71.7% | 74.4% | 71.2% | 46.7% |

| Yes, limited a little | 18.8% | 18.5% | 17.8% | 22.9% | |

| Yes, limited a lot | 9.6% | 7.1% | 11.0% | 30.4% | |

| IC7. Thinking about how much contact that you have had with people you like, which of the following statements best describes your social situation? | I have as much social contact as I want | 61.4% | 63.8% | 54.2% | 49.6% |

| I have adequate contact with people | 28.2% | 28.2% | 28.0% | 29.5% | |

| I have some social contact with people, but not enough | 8.2% | 6.8% | 12.9% | 14.3% | |

| I have little social contact with people and feel social isolated | 2.2% | 1.3% | 4.8% | 6.6% | |

| IC8. All things considered, how satisfied are you with your quality of life as a whole nowadays? | 1—Exceptionally dissatisfied | 1.2% | 1.1% | 1.2% | 2.0% |

| 2 | 1.9% | 1.8% | 1.9% | 3.2% | |

| 3 | 2.8% | 2.3% | 3.7% | 6.0% | |

| 4 | 2.8% | 2.0% | 4.8% | 6.9% | |

| 5 | 6.8% | 5.6% | 9.3% | 14.3% | |

| 6 | 6.9% | 6.2% | 10.0% | 8.3% | |

| 7 | 14.4% | 14.0% | 17.0% | 14.6% | |

| 8 | 29.1% | 30.6% | 25.9% | 20.1% | |

| 9 | 21.7% | 23.4% | 16.4% | 13.8% | |

| 10—Exceptionally satisfied | 12.4% | 13.0% | 9.8% | 10.9% | |

| IC9. Compared to 12 months ago, would you say your quality of life has… | Decreased significantly | 3.6% | 3.0% | 4.2% | 9.2% |

| Decreased to some extent | 19.0% | 18.2% | 18.3% | 27.2% | |

| Stayed about the same | 55.7% | 58.4% | 45.0% | 46.4% | |

| Increased to some extent | 16.6% | 15.9% | 24.3% | 12.0% | |

| Increased significantly | 5.1% | 4.6% | 8.1% | 5.2% | |

| IC10. Do you look after, or give any help or support to family members, friends, neighbours, or others because of either: (i) long-term physical or mental ill-health/disability? Or (ii) problems related to old age? | No | 61.8% | 60.7% | 68.0% | 63.3% |

| Yes, 1–19 h a week | 30.0% | 31.7% | 25.3% | 22.1% | |

| Yes, 20–49 h a week | 3.3% | 3.1% | 3.5% | 4.6% | |

| Yes, 50 or more hours a week | 4.8% | 4.5% | 3.3% | 10.0% | |

| IC11. In the last 28 days, how often have you been physically active? | Not at all | 4.6% | 3.4% | 5.0% | 14.9% |

| Less than once a week | 5.7% | 4.5% | 8.5% | 12.3% | |

| About once a week | 13.3% | 11.9% | 18.7% | 18.9% | |

| More than once a week | 76.4% | 80.2% | 67.8% | 53.9% | |

| IC12. Do you currently do any voluntary, unpaid work in your community (not including any support you give to family members)? Yes | 26.7% | 29.5% | 18.3% | 13.5% | |

| IC13. Have you experienced, witnessed, or heard about any form of discrimination in the last 12 months? Yes | 29.3% | 28.0% | 36.3% | 31.5% | |

| Living circumstances | |||||

| LC1. Overall, how satisfied are you with the state of repair of your home? | Very dissatisfied | 1.4% | 0.9% | 2.5% | 5.2% |

| Fairly dissatisfied | 6.4% | 5.7% | 8.9% | 10.0% | |

| Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied | 7.5% | 6.6% | 11.2% | 10.3% | |

| Fairly satisfied | 45.8% | 47.2% | 38.8% | 43.3% | |

| Very satisfied | 38.8% | 39.6% | 38.6% | 31.2% | |

| LC2. Do you think the quality of your home has a negative impact on your health? | A very negative impact | 2.9% | 2.3% | 3.5% | 8.0% |

| A fairly negative impact | 8.4% | 7.6% | 10.8% | 12.3% | |

| Not a very big impact | 18.6% | 17.5% | 23.6% | 21.2% | |

| No impact at all | 70.1% | 72.7% | 62.2% | 58.5% | |

| LC3. How much of a problem is it to find money to pay utility bills, i.e., electricity, gas, water, etc.? | A very big problem | 2.3% | 1.4% | 6.0% | 5.2% |

| A fairly big problem | 12.2% | 10.0% | 21.4% | 18.3% | |

| Not a very big problem | 30.8% | 29.1% | 37.1% | 37.8% | |

| Not a problem at all | 54.7% | 59.5% | 35.5% | 38.7% | |

| Neighbourhood circumstances | |||||

| NC1. Index of multiple deprivation decile | 1—Most deprived | 3.5% | 2.0% | 6.0% | 12.9% |

| 2 | 6.4% | 5.3% | 8.3% | 14.0% | |

| 3 | 15.3% | 14.0% | 16.8% | 24.6% | |

| 4 | 28.3% | 29.6% | 24.3% | 22.3% | |

| 5 | 20.4% | 20.5% | 21.6% | 17.2% | |

| 6 | 13.3% | 14.2% | 12.9% | 5.2% | |

| 7 | 7.6% | 8.5% | 5.4% | 2.3% | |

| 8 | 4.5% | 4.9% | 4.1% | 1.4% | |

| 9 | 0.8% | 0.9% | 0.6% | 0.0% | |

| 10—Least deprived | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| NC2. Overall, how satisfied or dissatisfied are you with your local area as a place to live? | Very dissatisfied | 2.5% | 2.5% | 1.9% | 3.7% |

| Fairly dissatisfied | 5.6% | 5.0% | 6.8% | 8.9% | |

| Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied | 7.7% | 7.1% | 11.2% | 8.3% | |

| Fairly satisfied | 44.7% | 45.1% | 44.6% | 41.3% | |

| Very satisfied | 39.6% | 40.4% | 35.5% | 37.8% | |

| NC3. Most needs improving—a sense of community | 8.0% | 8.1% | 7.7% | 7.7% | |

| NC4. Most needs improving—access to affordable childcare | 6.1% | 5.2% | 8.3% | 11.2% | |

| NC5. Most needs improving—access to nature | 3.0% | 3.0% | 2.7% | 2.6% | |

| NC6. Most needs improving—activities for teenagers | 18.9% | 19.3% | 14.7% | 21.8% | |

| NC7. Most needs improving—affordable decent housing | 37.8% | 37.0% | 45.4% | 34.1% | |

| NC8. Most needs improving—care for children and young people | 6.3% | 6.5% | 5.8% | 5.2% | |

| NC9. Most needs improving—care for the frail and elderly | 30.3% | 32.6% | 19.9% | 24.6% | |

| NC10. Most needs improving—clean streets | 13.7% | 13.8% | 12.7% | 13.5% | |

| NC11. Most needs improving—community activities | 5.8% | 5.4% | 6.8% | 8.3% | |

| NC12. Most needs improving—cultural activities | 9.0% | 8.7% | 11.0% | 8.6% | |

| NC13. Most needs improving—education provision | 8.9% | 9.6% | 6.0% | 6.3% | |

| NC14. Most needs improving—facilities for young children | 5.5% | 4.5% | 6.8% | 12.3% | |

| NC15. Most needs improving—GP services (National Health Service) | 27.2% | 28.2% | 24.5% | 22.3% | |

| NC16. Most needs improving—hospital services (National Health Service) | 33.0% | 35.4% | 26.6% | 21.2% | |

| NC17. Most needs improving—job prospects | 26.9% | 26.4% | 30.3% | 27.2% | |

| NC18. Most needs improving—parks and open spaces | 6.5% | 6.4% | 6.4% | 7.4% | |

| NC19. Most needs improving—public transport | 26.1% | 26.8% | 24.1% | 22.9% | |

| NC20. Most needs improving—road and pavement repairs | 37.7% | 40.0% | 31.5% | 25.2% | |

| NC21. Most needs improving—shopping facilities | 9.7% | 9.7% | 9.7% | 9.7% | |

| NC22. Most needs improving—sports and leisure facilities | 8.3% | 8.4% | 9.5% | 6.0% | |

| NC23. Most needs improving—the level of crime | 10.9% | 10.7% | 10.0% | 14.0% | |

| NC24. Most needs improving—the level of pollution | 4.9% | 5.5% | 4.2% | 0.9% | |

| NC25. Most needs improving—the level of traffic congestion | 29.3% | 31.4% | 22.2% | 20.6% | |

| NC26. Most needs improving—wage levels and the cost of living | 32.0% | 30.3% | 43.2% | 30.9% | |

| NC27. Do you agree or disagree that the council and the police are dealing with anti-social behaviour and crime issues that matter in your local area? | Strongly disagree | 9.8% | 9.2% | 11.0% | 13.2% |

| Tend to disagree | 19.9% | 20.1% | 19.7% | 18.3% | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 25.7% | 26.0% | 25.1% | 23.8% | |

| Tend to agree | 38.6% | 39.7% | 36.3% | 32.1% | |

| Strongly agree | 6.1% | 5.1% | 7.9% | 12.6% | |

| NC28. How safe or unsafe do you feel when outside in your local area during the day? | Very unsafe | 1.0% | 0.8% | 1.0% | 2.9% |

| Fairly unsafe | 3.1% | 2.8% | 2.9% | 6.0% | |

| Neither safe nor unsafe | 7.2% | 6.7% | 6.9% | 12.0% | |

| Fairly safe | 39.3% | 39.1% | 41.5% | 38.1% | |

| Very safe | 49.4% | 50.6% | 47.7% | 41.0% | |

| NC29. How safe or unsafe do you feel when outside in your local area after dark? | Very unsafe | 5.7% | 4.8% | 7.3% | 11.7% |

| Fairly unsafe | 12.8% | 11.9% | 15.6% | 17.5% | |

| Neither safe nor unsafe | 14.5% | 14.6% | 14.5% | 14.3% | |

| Fairly safe | 43.4% | 44.5% | 41.5% | 36.7% | |

| Very safe | 23.5% | 24.3% | 21.0% | 19.8% | |

| NC30. In your local area, how much of a problem is—street drinking or drunken behaviour in public places? | A very big problem | 11.0% | 9.9% | 15.1% | 15.2% |

| A fairly big problem | 25.5% | 25.6% | 25.9% | 23.5% | |

| Not a very big problem | 40.7% | 41.6% | 39.8% | 33.5% | |

| Not a problem at all | 22.9% | 22.9% | 19.3% | 27.8% | |

| NC31. In your local area, how much of a problem is—people using or dealing drugs? | A very big problem | 13.5% | 12.1% | 18.9% | 18.9% |

| A fairly big problem | 26.1% | 26.8% | 24.5% | 22.6% | |

| Not a very big problem | 35.0% | 35.9% | 33.6% | 28.9% | |

| Not a problem at all | 25.3% | 25.2% | 23.0% | 29.5% | |

| NC32. In your local area, how much of a problem is—begging, vagrancy, or homeless people on the streets? | A very big problem | 9.3% | 8.5% | 12.4% | 11.5% |

| A fairly big problem | 16.9% | 17.2% | 16.6% | 15.2% | |

| Not a very big problem | 35.1% | 35.7% | 35.9% | 28.4% | |

| Not a problem at all | 38.7% | 38.6% | 35.1% | 45.0% | |

| NC33. In your local area, how much of a problem is—people being intimidated, verbally abused, or harassed? | A very big problem | 5.2% | 4.0% | 9.1% | 9.7% |

| A fairly big problem | 11.4% | 10.6% | 14.7% | 13.8% | |

| Not a very big problem | 43.2% | 44.5% | 39.2% | 37.8% | |

| Not a problem at all | 40.2% | 40.9% | 37.1% | 38.7% | |

| NC34. In your local area, how much of a problem is—theft? | A very big problem | 5.5% | 4.5% | 10.2% | 7.2% |

| A fairly big problem | 22.6% | 22.1% | 22.4% | 28.1% | |

| Not a very big problem | 54.6% | 57.3% | 49.8% | 37.2% | |

| Not a problem at all | 17.3% | 16.1% | 17.6% | 27.5% | |

| NC35. In your local area, how much of a problem is—vandalism, criminal damage, or graffiti? | A very big problem | 7.8% | 6.7% | 12.0% | 11.5% |

| A fairly big problem | 23.7% | 23.9% | 23.2% | 22.9% | |

| Not a very big problem | 48.7% | 50.4% | 43.1% | 41.0% | |

| Not a problem at all | 19.9% | 19.0% | 21.8% | 24.6% | |

| NC36. In your local area, how much of a problem is—loud music or other noise? | A very big problem | 5.5% | 4.5% | 8.5% | 10.6% |

| A fairly big problem | 13.3% | 12.8% | 14.3% | 16.0% | |

| Not a very big problem | 51.7% | 53.6% | 48.1% | 39.8% | |

| Not a problem at all | 29.5% | 29.1% | 29.2% | 33.5% | |

| NC37. In your local area, how much of a problem is—environmental nuisance? | A very big problem | 17.9% | 17.3% | 19.9% | 20.9% |

| A fairly big problem | 39.0% | 40.5% | 33.2% | 34.4% | |

| Not a very big problem | 33.4% | 34.0% | 34.0% | 27.5% | |

| Not a problem at all | 9.6% | 8.3% | 12.9% | 17.2% | |

| NC38. In your local area, how much of a problem is—vehicle-related nuisance? | A very big problem | 11.2% | 10.6% | 13.3% | 14.3% |

| A fairly big problem | 22.7% | 23.2% | 19.9% | 21.8% | |

| Not a very big problem | 42.9% | 44.2% | 41.3% | 33.8% | |

| Not a problem at all | 23.2% | 22.1% | 25.5% | 30.1% | |

| NC39. In your local area, how much of a problem is—out of control or dangerous dogs? | A very big problem | 2.5% | 2.2% | 3.1% | 4.0% |

| A fairly big problem | 7.7% | 7.5% | 7.5% | 10.0% | |

| Not a very big problem | 48.4% | 50.7% | 41.3% | 37.2% | |

| Not a problem at all | 41.4% | 39.5% | 48.1% | 48.7% | |

| NC40. To what extent do you agree or disagree that your local area is a place where people from different backgrounds get on well together? | Strongly disagree | 1.6% | 1.3% | 1.9% | 4.0% |

| Tend to disagree | 6.6% | 6.2% | 8.7% | 7.2% | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 27.5% | 27.1% | 28.4% | 29.8% | |

| Tend to agree | 52.3% | 53.7% | 48.8% | 44.1% | |

| Strongly agree | 12.0% | 11.7% | 12.2% | 14.9% | |

| NC41. In your local area, how much of a problem do you think there is with people not treating each other with respect and consideration? | A very big problem | 2.7% | 2.4% | 2.3% | 6.3% |

| A fairly big problem | 11.1% | 9.5% | 16.6% | 17.2% | |

| Not a very big problem | 58.3% | 59.2% | 55.4% | 54.2% | |

| Not a problem at all | 27.9% | 28.9% | 25.7% | 22.3% | |

Appendix B

| Complete Responses | Missing Responses | Number Missing | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual Circumstances | n = 4085 | n = 7162 | n = 7162 | |

| IC1. Age group | 16–17 y | 1.7% | 2.0% | 282 |

| 18–24 y | 3.6% | 3.9% | ||

| 25–34 y | 8.7% | 6.4% | ||

| 35–44 y | 12.9% | 7.9% | ||

| 45–54 y | 19.3% | 12.9% | ||

| 55–64 y | 22.5% | 17.3% | ||

| 65–74 y | 22.2% | 26.3% | ||

| 75–84 y | 7.4% | 17.1% | ||

| 85+ y | 1.7% | 6.1% | ||

| IC2. Gender | Female | 52.3% | 58.7% | 383 |

| Male | 47.7% | 41.3% | ||

| IC3. Ethnicity | White | 98.9% | 98.6% | 359 |

| Other | 1.1% | 1.4% | ||

| IC4. Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (SWEMWBS) score | 24.56 ± 4.64 | 24.40 ± 4.97 | 639 | |

| IC5. How is your health in general? | Very bad | 1.1% | 2.1% | 210 |

| Bad | 4.7% | 7.7% | ||

| Fair | 19.2% | 26.8% | ||

| Good | 45.4% | 40.5% | ||

| Very good | 29.5% | 22.9% | ||

| IC6. Are your day-to-day activities limited because of a health problem or disability that has lasted, or is expected to last, at least 12 months (including problems related to old age)? | No | 71.7% | 60.0% | 287 |

| Yes, limited a little | 18.8% | 23.5% | ||

| Yes, limited a lot | 9.6% | 16.5% | ||

| IC7. Thinking about how much contact that you have had with people you like, which of the following statements best describes your social situation? | I have as much social contact as I want | 61.4% | 55.9% | 231 |

| I have adequate contact with people | 28.2% | 32.0% | ||

| I have some social contact with people, but not enough | 8.2% | 8.9% | ||

| I have little social contact with people and feel social isolated | 2.2% | 3.2% | ||

| IC8. All things considered, how satisfied are you with your quality of life as a whole nowadays? | 1—Exceptionally dissatisfied | 1.2% | 1.7% | 227 |

| 2 | 1.9% | 2.0% | ||

| 3 | 2.8% | 3.3% | ||

| 4 | 2.8% | 3.2% | ||

| 5 | 6.8% | 8.5% | ||

| 6 | 6.9% | 6.9% | ||

| 7 | 14.4% | 14.1% | ||

| 8 | 29.1% | 26.5% | ||

| 9 | 21.7% | 18.7% | ||

| 10—Exceptionally satisfied | 12.4% | 15.2% | ||

| IC9. Compared to 12 months ago, would you say your quality of life has… | Decreased significantly | 3.6% | 5.0% | 274 |

| Decreased to some extent | 19.0% | 21.5% | ||

| Stayed about the same | 55.7% | 56.7% | ||

| Increased to some extent | 16.6% | 12.2% | ||

| Increased significantly | 5.1% | 4.6% | ||

| IC10. Do you look after, or give any help or support to family members, friends, neighbours, or others because of either: i) long-term physical or mental ill-health/disability? Or ii) problems related to old age? | No | 61.8% | 66.6% | 444 |

| Yes, 1–19 h a week | 30.0% | 24.1% | ||

| Yes, 20–49 h a week | 3.3% | 3.5% | ||

| Yes, 50 or more hours a week | 4.8% | 5.9% | ||

| IC11. In the last 28 days, how often have you been physically active? | Not at all | 4.6% | 9.7% | 313 |

| Less than once a week | 5.7% | 6.3% | ||

| About once a week | 13.3% | 13.6% | ||

| More than once a week | 76.4% | 70.3% | ||

| IC12. Do you currently do any voluntary, unpaid work in your community (not including any support you give to family members)? Yes | 26.7% | 20.3% | 249 | |

| IC13. Have you experienced, witnessed, or heard about any form of discrimination in the last 12 months? Yes | 29.3% | 19.2% | 1228 | |

| Living circumstances | ||||

| LC0. Tenure | Owner occupier | 78.8% | 78.1% | 471 |

| Private renter | 12.7% | 10.4% | ||

| Social housing resident | 8.5% | 11.4% | ||

| LC1. Overall, how satisfied are you with the state of repair of your home? | Very dissatisfied | 1.4% | 1.8% | 245 |

| Fairly dissatisfied | 6.4% | 5.2% | ||

| Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied | 7.5% | 7.3% | ||

| Fairly satisfied | 45.8% | 42.6% | ||

| Very satisfied | 38.8% | 43.2% | ||

| LC2. Do you think the quality of your home has a negative impact on your health? | A very negative impact | 2.9% | 4.6% | 776 |

| A fairly negative impact | 8.4% | 7.5% | ||

| Not a very big impact | 18.6% | 17.2% | ||

| No impact at all | 70.1% | 70.7% | ||

| LC3. How much of a problem is it to find money to pay utility bills i.e., electricity, gas, water, etc.? | A very big problem | 2.3% | 2.9% | 1085 |

| A fairly big problem | 12.2% | 12.0% | ||

| Not a very big problem | 30.8% | 28.3% | ||

| Not a problem at all | 54.7% | 56.8% | ||

| Neighbourhood circumstances | ||||

| NC1. Index of multiple deprivation decile | 1—Most deprived | 3.5% | 3.5% | 1 |

| 2 | 6.4% | 7.5% | ||

| 3 | 15.3% | 14.8% | ||

| 4 | 28.3% | 29.9% | ||

| 5 | 20.4% | 20.8% | ||

| 6 | 13.3% | 10.6% | ||

| 7 | 7.6% | 7.5% | ||

| 8 | 4.5% | 4.6% | ||

| 9 | 0.8% | 0.8% | ||

| 10—Least deprived | 0.0% | 0.0% | ||

| NC2. Overall, how satisfied or dissatisfied are you with your local area as a place to live? | Very dissatisfied | 2.5% | 3.2% | 142 |

| Fairly dissatisfied | 5.6% | 5.9% | ||

| Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied | 7.7% | 8.3% | ||

| Fairly satisfied | 44.7% | 43.3% | ||

| Very satisfied | 39.6% | 39.2% | ||

| NC3. Most needs improving—a sense of community | 8.0% | 7.1% | 0 | |

| NC4. Most needs improving—access to affordable childcare | 6.1% | 5.1% | 0 | |

| NC5. Most needs improving—access to nature | 3.0% | 3.0% | 0 | |

| NC6. Most needs improving—activities for teenagers | 18.9% | 16.5% | 0 | |

| NC7. Most needs improving—affordable decent housing | 37.8% | 30.3% | 0 | |

| NC8. Most needs improving—care for children and young people | 6.3% | 5.3% | 0 | |

| NC9. Most needs improving—care for the frail and elderly | 30.3% | 27.7% | 0 | |

| NC10. Most needs improving—clean streets | 13.7% | 14.9% | 0 | |

| NC11. Most needs improving—community activities | 5.8% | 5.7% | 0 | |

| NC12. Most needs improving—cultural activities | 9.0% | 7.8% | 0 | |

| NC13. Most needs improving—education provision | 8.9% | 6.9% | 0 | |

| NC14. Most needs improving—facilities for young children | 5.5% | 5.1% | 0 | |

| NC15. Most needs improving—GP services (NHS) | 27.2% | 23.8% | 0 | |

| NC16. Most needs improving—hospital services (NHS) | 33.0% | 28.8% | 0 | |

| NC17. Most needs improving—job prospects | 26.9% | 21.2% | 0 | |

| NC18. Most needs improving—parks and open spaces | 6.5% | 5.9% | 0 | |

| NC19. Most needs improving—public transport | 26.1% | 23.2% | 0 | |

| NC20. Most needs improving—road and pavement repairs | 37.7% | 34.7% | 0 | |

| NC21. Most needs improving—shopping facilities | 9.7% | 9.5% | 0 | |

| NC22. Most needs improving—sports and leisure facilities | 8.3% | 6.3% | 0 | |

| NC23. Most needs improving—the level of crime | 10.9% | 10.3% | 0 | |

| NC24. Most needs improving—the level of pollution | 4.9% | 5.6% | 0 | |

| NC25. Most needs improving—the level of traffic congestion | 29.3% | 27.6% | 0 | |

| NC26. Most needs improving—wage levels and the cost of living | 32.0% | 25.3% | 0 | |

| NC27. Do you agree or disagree that the council and the police are dealing with anti-social behaviour and crime issues that matter in your local area? | Strongly disagree | 9.8% | 9.5% | 1846 |

| Tend to disagree | 19.9% | 18.3% | ||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 25.7% | 30.0% | ||

| Tend to agree | 38.6% | 35.4% | ||

| Strongly agree | 6.1% | 6.9% | ||

| NC28. How safe or unsafe do you feel when outside in your local area during the day? | Very unsafe | 1.0% | 1.5% | 307 |

| Fairly unsafe | 3.1% | 3.6% | ||

| Neither safe nor unsafe | 7.2% | 9.4% | ||

| Fairly safe | 39.3% | 42.7% | ||

| Very safe | 49.4% | 42.8% | ||

| NC29. How safe or unsafe do you feel when outside in your local area after dark? | Very unsafe | 5.7% | 6.7% | 1235 |

| Fairly unsafe | 12.8% | 13.1% | ||

| Neither safe nor unsafe | 14.5% | 17.5% | ||

| Fairly safe | 43.4% | 40.9% | ||

| Very safe | 23.5% | 21.8% | ||

| NC30. In your local area, how much of a problem is—street drinking or drunken behaviour in public places? | A very big problem | 11.0% | 11.9% | 1568 |

| A fairly big problem | 25.5% | 25.7% | ||

| Not a very big problem | 40.7% | 39.0% | ||

| Not a problem at all | 22.9% | 23.4% | ||

| NC31. In your local area, how much of a problem is—people using or dealing drugs? | A very big problem | 13.5% | 18.2% | 2762 |

| A fairly big problem | 26.1% | 28.5% | ||

| Not a very big problem | 35.0% | 26.9% | ||

| Not a problem at all | 25.3% | 26.3% | ||

| NC32. In your local area, how much of a problem is—begging, vagrancy, or homeless people on the streets? | A very big problem | 9.3% | 10.9% | 1524 |

| A fairly big problem | 16.9% | 18.9% | ||

| Not a very big problem | 35.1% | 31.5% | ||

| Not a problem at all | 38.7% | 38.7% | ||

| NC33. In your local area, how much of a problem is—people being intimidated, verbally abused, or harassed? | A very big problem | 5.2% | 6.4% | 2473 |

| A fairly big problem | 11.4% | 13.1% | ||

| Not a very big problem | 43.2% | 36.3% | ||

| Not a problem at all | 40.2% | 44.1% | ||

| NC34. In your local area, how much of a problem is—theft? | A very big problem | 5.5% | 7.5% | 2326 |

| A fairly big problem | 22.6% | 23.6% | ||

| Not a very big problem | 54.6% | 49.2% | ||

| Not a problem at all | 17.3% | 19.7% | ||

| NC35. In your local area, how much of a problem is—vandalism, criminal damage, or graffiti? | A very big problem | 7.8% | 8.3% | 1846 |

| A fairly big problem | 23.7% | 24.4% | ||

| Not a very big problem | 48.7% | 44.6% | ||

| Not a problem at all | 19.9% | 22.7% | ||

| NC36. In your local area, how much of a problem is—loud music or other noise? | A very big problem | 5.5% | 6.7% | 1493 |

| A fairly big problem | 13.3% | 14.0% | ||

| Not a very big problem | 51.7% | 45.4% | ||

| Not a problem at all | 29.5% | 33.9% | ||

| NC37. In your local area, how much of a problem is—environmental nuisance? | A very big problem | 17.9% | 19.3% | 781 |

| A fairly big problem | 39.0% | 36.5% | ||

| Not a very big problem | 33.4% | 33.1% | ||

| Not a problem at all | 9.6% | 11.1% | ||

| NC38. In your local area, how much of a problem is—vehicle-related nuisance? | A very big problem | 11.2% | 13.6% | 1321 |

| A fairly big problem | 22.7% | 22.2% | ||

| Not a very big problem | 42.9% | 39.8% | ||

| Not a problem at all | 23.2% | 24.4% | ||

| NC39. In your local area, how much of a problem is—out of control or dangerous dogs? | A very big problem | 2.5% | 4.0% | 1888 |

| A fairly big problem | 7.7% | 8.8% | ||

| Not a very big problem | 48.4% | 40.5% | ||

| Not a problem at all | 41.4% | 46.8% | ||

| NC40. To what extent do you agree or disagree that your local area is a place where people from different backgrounds get on well together? | Strongly disagree | 1.6% | 1.8% | 1431 |

| Tend to disagree | 6.6% | 5.9% | ||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 27.5% | 31.4% | ||

| Tend to agree | 52.3% | 48.5% | ||

| Strongly agree | 12.0% | 12.4% | ||

| NC41. In your local area, how much of a problem do you think there is with people not treating each other with respect and consideration? | A very big problem | 2.7% | 3.0% | 1152 |

| A fairly big problem | 11.1% | 11.2% | ||

| Not a very big problem | 58.3% | 51.8% | ||

| Not a problem at all | 27.9% | 33.9% | ||

Appendix C

| Individual Circumstances | Mean | SD | Area Circumstances (Cont.) | Mean | SD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC1. Age group | 16–17 y | 24.26 | 5.05 | NC10. Most needs improving—clean streets | No | 24.57 | 4.65 |

| 18–24 y | 24.18 | 4.48 | Yes | 24.50 | 4.60 | ||

| 25–34 y | 24.32 | 4.72 | NC11. Most needs improving—community activities | No | 24.57 | 4.63 | |

| 35–44 y | 24.40 | 4.81 | Yes | 24.39 | 4.75 | ||

| 45–54 y | 24.31 | 4.92 | NC12. Most needs improving—cultural activities | No | 24.58 | 4.65 | |

| 55–64 y | 24.37 | 4.60 | Yes | 24.37 | 4.55 | ||

| 65–74 y | 25.17 | 4.26 | NC13. Most needs improving—education provision | No | 24.52 | 4.66 | |

| 75–84 y | 24.91 | 4.67 | Yes | 24.97 | 4.40 | ||

| 85 + y | 23.83 | 4.09 | NC14. Most needs improving—facilities for young children | No | 24.57 | 4.62 | |

| IC2. Gender | Female | 24.69 | 4.80 | Yes | 24.37 | 4.99 | |

| Male | 24.41 | 4.46 | NC15. Most needs improving—GP services (NHS) | No | 24.58 | 4.63 | |

| IC3. Ethnicity | White | 24.56 | 4.64 | Yes | 24.49 | 4.68 | |

| Other | 24.26 | 4.43 | NC16. Most needs improving—hospital services (NHS) | No | 24.50 | 4.70 | |

| IC5. How is your health in general? | Very bad | 18.39 | 4.37 | Yes | 24.66 | 4.52 | |

| Bad | 19.97 | 4.22 | NC17. Most needs improving—job prospects | No | 24.57 | 4.69 | |

| Fair | 22.72 | 3.95 | Yes | 24.52 | 4.50 | ||

| Good | 24.60 | 4.12 | NC18. Most needs improving—parks and open spaces | No | 24.58 | 4.62 | |

| Very good | 26.67 | 4.65 | Yes | 24.29 | 4.91 | ||

| IC6. Are your day-to-day activities limited because of a health problem or disability that has lasted, or is expected to last, at least 12 months (including problems related to old age)? | No | 25.26 | 4.47 | NC19. Most needs improving—public transport | No | 24.54 | 4.65 |

| Yes, limited a little | 23.72 | 4.43 | Yes | 24.61 | 4.63 | ||

| Yes, limited a lot | 20.93 | 4.35 | NC20. Most needs improving—road and pavement repairs | No | 24.44 | 4.76 | |

| Yes | 24.74 | 4.43 | |||||

| IC7. Thinking about how much contact that you have had with people you like, which of the following statements best describes your social situation? | I have as much social contact as I want | 25.99 | 4.48 | NC21. Most needs improving—shopping facilities | No | 24.63 | 4.67 |

| Yes | 23.85 | 4.32 | |||||

| I have adequate contact with people | 23.00 | 3.67 | NC22. Most needs improving—sports and leisure facilities | No | 24.56 | 4.64 | |

| Yes | 24.53 | 4.70 | |||||

| I have some social contact with people, but not enough | 20.91 | 3.66 | NC23. Most needs improving—the level of crime | No | 24.60 | 4.62 | |

| Yes | 24.19 | 4.77 | |||||

| I have little social contact with people and feel social isolated | 18.13 | 4.42 | NC24. Most needs improving—the level of pollution | No | 24.56 | 4.66 | |

| Yes | 24.47 | 4.30 | |||||

| IC8. All things considered, how satisfied are you with your quality of life as a whole nowadays? | 1—Exceptionally dissatisfied | 23.30 | 8.56 | NC25. Most needs improving—the level of traffic congestion | No | 24.57 | 4.71 |

| 2 | 22.75 | 5.93 | |||||

| 3 | 20.74 | 4.05 | Yes | 24.53 | 4.48 | ||

| 4 | 19.29 | 2.82 | NC26. Most needs improving—wage levels and the cost of living | No | 24.62 | 4.65 | |

| 5 | 20.68 | 2.88 | Yes | 24.42 | 4.61 | ||

| 6 | 21.37 | 3.29 | NC27. Do you agree or disagree that the council and the police are dealing with anti-social behaviour and crime issues that matter in your local area? | Very dissatisfied | 23.62 | 5.02 | |

| 7 | 22.61 | 3.23 | Fairly dissatisfied | 23.95 | 4.45 | ||

| 8 | 24.33 | 3.33 | Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied | 24.00 | 4.46 | ||

| 9 | 26.75 | 3.72 | Fairly satisfied | 25.24 | 4.50 | ||

| 10—Exceptionally satisfied | 29.86 | 4.27 | Very satisfied | 26.05 | 5.26 | ||

| IC9. Compared to 12 months ago, would you say your quality of life has… | Decreased significantly | 20.13 | 4.19 | NC28. How safe or unsafe do you feel when outside in your local area during the day? | Very unsafe | 21.02 | 5.68 |

| Decreased to some extent | 22.45 | 3.99 | Fairly unsafe | 22.18 | 4.24 | ||

| Stayed about the same | 24.98 | 4.51 | Neither safe nor unsafe | 23.04 | 4.80 | ||

| Increased to some extent | 25.63 | 4.33 | Fairly safe | 23.81 | 4.44 | ||

| Increased significantly | 27.46 | 4.75 | Very safe | 25.59 | 4.52 | ||

| IC10. Do you look after, or give any help or support to family members, friends, neighbours, or others because of either: (i) long-term physical or mental ill-health/disability? Or (ii) problems related to old age? | No | 24.57 | 4.70 | NC29. How safe or unsafe do you feel when outside in your local area after dark? | Very unsafe | 22.68 | 5.13 |

| Yes, 1–19 h a week | 24.74 | 4.54 | Fairly unsafe | 23.54 | 4.62 | ||

| Yes, 20–49 h a week | 23.69 | 4.02 | Neither safe nor unsafe | 23.28 | 4.46 | ||

| Yes, 50 or more hours a week | 23.83 | 4.83 | |||||

| Fairly safe | 24.70 | 4.39 | |||||

| Very safe | 26.09 | 4.59 | |||||

| IC11. In the last 28 days, how often have you been physically active? | Not at all | 21.80 | 5.04 | NC30. In your local area, how much of a problem is—street drinking or drunken behaviour in public places? | A very big problem | 23.81 | 5.00 |

| Less than once a week | 22.26 | 4.79 | A fairly big problem | 24.22 | 4.46 | ||

| About once a week | 23.70 | 4.43 | Not a very big problem | 24.49 | 4.43 | ||

| More than once a week | 25.05 | 4.51 | Not a problem at all | 25.42 | 4.90 | ||

| IC12. Do you currently do any voluntary, unpaid work in your community (not including any support you give to family members)? | No | 24.38 | 4.68 | NC31. In your local area, how much of a problem is—people using or dealing drugs? | A very big problem | 23.91 | 5.21 |

| A fairly big problem | 24.23 | 4.40 | |||||

| Yes | 25.05 | 4.50 | Not a very big problem | 24.47 | 4.36 | ||

| Not a problem at all | 25.36 | 4.84 | |||||

| IC13. Have you experienced, witnessed, or heard about any form of discrimination in the last 12 months? | No | 24.88 | 4.60 | NC32. In your local area, how much of a problem is—begging, vagrancy, or homeless people on the streets? | A very big problem | 23.99 | 4.83 |

| A fairly big problem | 24.14 | 4.56 | |||||

| Yes | 23.77 | 4.65 | Not a very big problem | 24.39 | 4.38 | ||

| Not a problem at all | 25.03 | 4.82 | |||||

| Living circumstances | |||||||

| LC1. Overall, how satisfied are you with the state of repair of your home? | Very dissatisfied | 21.40 | 6.35 | NC33. In your local area, how much of a problem is—people being intimidated, verbally abused, or harassed? | A very big problem | 23.74 | 5.27 |

| Fairly dissatisfied | 22.71 | 4.58 | A fairly big problem | 23.39 | 4.59 | ||

| Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied | 22.57 | 4.02 | Not a very big problem | 24.36 | 4.33 | ||

| Fairly satisfied | 24.08 | 4.20 | Not a problem at all | 25.20 | 4.79 | ||

| Very satisfied | 25.93 | 4.77 | |||||

| LC2. Do you think the quality of your home has a negative impact on your health? | A very negative impact | 22.92 | 6.30 | NC34. In your local area, how much of a problem is—theft? | A very big problem | 23.48 | 5.20 |

| A fairly negative impact | 22.27 | 4.06 | A fairly big problem | 24.01 | 4.58 | ||

| Not a very big impact | 23.00 | 4.03 | Not a very big problem | 24.65 | 4.36 | ||

| No impact at all | 25.31 | 4.57 | Not a problem at all | 25.33 | 5.22 | ||

| LC3. How much of a problem is it to find money to pay utility bills i.e., electricity, gas, water, etc.? | A very big problem | 22.05 | 5.46 | NC35. In your local area, how much of a problem is—vandalism, criminal damage, or graffiti? | A very big problem | 23.51 | 5.00 |

| A fairly big problem | 22.27 | 4.25 | A fairly big problem | 24.07 | 4.52 | ||

| Not a very big problem | 23.63 | 4.19 | Not a very big problem | 24.60 | 4.37 | ||

| Not a problem at all | 25.69 | 4.59 | Not a problem at all | 25.44 | 5.09 | ||

| Area circumstances | |||||||

| NC1. Index of multiple deprivation decile | 1—most deprived | 23.57 | 4.95 | NC36. In your local area, how much of a problem is—loud music or other noise? | A very big problem | 23.50 | 5.13 |

| 2 | 24.07 | 5.26 | A fairly big problem | 23.76 | 4.70 | ||

| 3 | 24.01 | 4.58 | Not a very big problem | 24.41 | 4.33 | ||

| 4 | 24.71 | 4.54 | Not a problem at all | 25.38 | 4.91 | ||

| 5 | 24.81 | 4.64 | NC37. In your local area, how much of a problem is—environmental nuisance? | A very big problem | 24.19 | 4.85 | |

| 6 | 24.63 | 4.80 | A fairly big problem | 24.20 | 4.38 | ||

| 7 | 25.08 | 4.40 | Not a very big problem | 24.88 | 4.57 | ||

| 8 | 24.53 | 3.89 | Not a problem at all | 25.54 | 5.25 | ||

| 9 | 25.39 | 4.90 | NC38. In your local area, how much of a problem is—vehicle-related nuisance? | A very big problem | 23.78 | 4.89 | |

| A fairly big problem | 24.09 | 4.62 | |||||

| 10—least deprived | - | - | Not a very big problem | 24.56 | 4.40 | ||

| Not a problem at all | 25.39 | 4.85 | |||||

| NC2. Overall, how satisfied or dissatisfied are you with your local area as a place to live? | Very dissatisfied | 22.13 | 5.38 | NC39. In your local area, how much of a problem is—out of control or dangerous dogs? | A very big problem | 23.23 | 5.13 |

| Fairly dissatisfied | 23.39 | 5.00 | A fairly big problem | 23.96 | 4.88 | ||

| Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied | 23.12 | 4.68 | Not a very big problem | 24.34 | 4.32 | ||

| Fairly satisfied | 24.17 | 4.32 | Not a problem at all | 25.00 | 4.88 | ||

| Very satisfied | 25.59 | 4.65 | |||||

| NC3. Most needs improving—a sense of community | No | 24.61 | 4.65 | NC40. To what extent do you agree or disagree that your local area is a place where people from different backgrounds get on well together? | Strongly disagree | 22.90 | 5.66 |

| Yes | 23.98 | 4.50 | Tend to disagree | 23.23 | 5.00 | ||

| NC4. Most needs improving—access to affordable childcare | No | 24.56 | 4.66 | Neither agree nor disagree | 23.73 | 4.55 | |

| Yes | 24.53 | 4.39 | |||||

| NC5. Most needs improving—access to nature | No | 24.57 | 4.64 | Tend to agree | 24.77 | 4.36 | |

| Yes | 24.26 | 4.78 | |||||

| NC6. Most needs improving—activities for teenagers | No | 24.54 | 4.69 | Strongly agree | 26.46 | 4.95 | |

| Yes | 24.64 | 4.41 | |||||

| NC7. Most needs improving—affordable decent housing | No | 24.64 | 4.78 | NC41. In your local area, how much of a problem do you think there is with people not treating each other with respect and consideration? | A very big problem | 22.02 | 5.64 |

| Yes | 24.42 | 4.40 | A fairly big problem | 23.24 | 4.55 | ||

| NC8. Most needs improving—care for children and young people | No | 24.54 | 4.65 | Not a very big problem | 24.26 | 4.33 | |

| Yes | 24.87 | 4.48 | Not a problem at all | 25.95 | 4.83 | ||

| NC9. Most needs improving—care for the frail and elderly | No | 24.55 | 4.77 | ||||

| Yes | 24.58 | 4.33 |

Appendix D

| Privately Owned | Private Rentals | Social Housing | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual Circumstances | Coef. | 95% CI | Coef. | 95%CI | Coef. | 95% CI | |

| Intercept | 25.30 | 24.86 to 25.74 | 26.16 | 24.85 to 27.47 | 24.82 | 23.39 to 26.24 | |

| IC1. Age group | 16–17 y | −3.42 | −6.62 to −0.22 | ||||

| 18–24 y | −1.87 | −3.26 to −0.47 | |||||

| 25–34 y | −1.16 | −2.27 to −0.05 | |||||

| 35–44 y | −1.22 | −2.33 to −0.10 | |||||

| 45–54 y | −1.07 | −2.19 to 0.04 | |||||

| 55–64 y | −1.11 | −2.26 to 0.04 | |||||

| 65–74 y | (ref) | ||||||

| 75–84 y | 2.03 | −0.05 to 4.11 | |||||

| 85+ y | −1.87 | −5.82 to 2.08 | |||||

| IC5. How is your health in general? | Very bad | −1.37 | −2.82 to 0.09 | −3.34 | −6.62 to −0.05 | −4.25 | −6.33 to −2.17 |

| Bad | −1.02 | −1.86 to −0.19 | −2.38 | −3.68 to −1.09 | −0.83 | −2.13 to 0.48 | |

| Fair | −0.53 | −0.90 to −0.16 | −1.00 | −1.90 to −0.11 | −0.69 | −1.69 to 0.31 | |

| Good | (ref) | (ref) | (ref) | ||||

| Very good | 0.76 | 0.48 to 1.05 | 1.13 | 0.41 to 1.86 | 1.64 | 0.51 to 2.78 | |

| IC6. Are your day-to-day activities limited because of a health problem or disability that has lasted, or is expected to last, at least 12 months (including problems related to old age)? | No | (ref) | |||||

| Yes, limited a little | 0.48 | 0.13 to 0.83 | |||||

| Yes, limited a lot | 0.29 | −0.32 to 0.89 | |||||

| IC7. Thinking about how much contact that you have had with people you like, which of the following statements best describes your social situation? | I have as much social contact as I want | (ref) | (ref) | (ref) | |||

| I have adequate contact with people | −1.29 | −1.57 to −1.02 | −1.03 | −1.76 to −0.31 | −1.44 | −2.35 to −0.53 | |

| I have some social contact with people, but not enough | −2.06 | −2.56 to −1.56 | −1.45 | −2.43 to −0.47 | −2.69 | −3.93 to −1.45 | |

| I have little social contact with people and feel social isolated | −3.18 | −4.29 to −2.07 | −3.72 | −5.36 to −2.09 | −2.87 | −4.61 to −1.12 | |

| IC8. All things considered, how satisfied are you with your quality of life as a whole nowadays? | 1—Exceptionally dissatisfied | 1.83 | 0.67 to 2.99 | −3.43 | −6.59 to −0.27 | −5.89 | −8.87 to −2.90 |

| 2 | 0.60 | −0.32 to 1.52 | −2.19 | −4.50 to 0.13 | −2.74 | −5.14 to −0.34 | |

| 3 | −1.58 | −2.42 to −0.74 | −1.61 | −3.28 to 0.07 | −4.82 | −6.58 to −3.06 | |

| 4 | −2.82 | −3.70 to −1.95 | −3.11 | −4.68 to −1.55 | −3.89 | −5.65 to −2.12 | |

| 5 | −1.96 | −2.53 to −1.40 | −2.63 | −3.82 to −1.44 | −1.89 | −3.23 to −0.55 | |

| 6 | −1.88 | −2.41 to −1.35 | −1.66 | −2.81 to −0.51 | −2.07 | −3.61 to −0.53 | |

| 7 | −1.19 | −1.57 to −0.81 | −1.55 | −2.48 to −0.63 | −0.46 | −1.74 to 0.83 | |

| 8 | (ref) | (ref) | (ref) | ||||

| 9 | 1.88 | 1.55 to 2.20 | 0.80 | −0.14 to 1.73 | 1.65 | 0.29 to 3.02 | |

| 10—Exceptionally satisfied | 4.44 | 4.02 to 4.85 | 3.84 | 2.72 to 4.96 | 4.27 | 2.79 to 5.75 | |

| IC9. Compared to 12 months ago, would you say your quality of life has… | Decreased significantly | −1.62 | −2.41 to −0.83 | ||||

| Decreased to some extent | −0.40 | −0.74 to −0.07 | |||||

| Stayed about the same | (ref) | ||||||

| Increased to some extent | 0.11 | −0.22 to 0.44 | |||||

| Increased significantly | 0.99 | 0.42 to 1.56 | |||||

| IC10. Do you look after, or give any help or support to family members, friends, neighbours, or others because of either: (i) long-term physical or mental ill-health/disability? Or (ii) problems related to old age? | No | (ref) | |||||

| Yes, 1–19 h a week | 0.72 | 0.03 to 1.42 | |||||

| Yes, 20–49 h a week | −1.00 | −2.65 to 0.64 | |||||

| Yes, 50 or more hours a week | 0.77 | −0.93 to 2.47 | |||||

| Living circumstances | |||||||

| LC1. Overall, how satisfied are you with the state of repair of your home? | Very dissatisfied | −0.52 | −1.80 to 0.77 | ||||

| Fairly dissatisfied | 0.08 | −0.47 to 0.63 | |||||

| Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied | −0.13 | −0.62 to 0.37 | |||||

| Fairly satisfied | (ref) | ||||||

| Very satisfied | 0.49 | 0.22 to 0.75 | |||||

| LC2. Do you think the quality of your home has a negative impact on your health? | A very negative impact | −0.49 | −1.28 to 0.31 | ||||

| A fairly negative impact | −0.66 | −1.15 to −0.17 | |||||

| Not a very big impact | −0.25 | −0.59 to 0.09 | |||||

| No impact at all | (ref) | ||||||

| LC3. How much of a problem is it to find money to pay utility bills i.e., electricity, gas, water, etc.? | A very big problem | 0.25 | −0.76 to 1.27 | −1.36 | −2.82 to 0.10 | ||

| A fairly big problem | −0.58 | −1.01 to −0.16 | −1.48 | −2.33 to −0.64 | |||

| Not a very big problem | −0.67 | −0.95 to −0.40 | −0.93 | −1.64 to −0.23 | |||

| Not a problem at all | (ref) | (ref) | |||||

| Neighbourhood circumstances | |||||||

| NC2. Overall, how satisfied or dissatisfied are you with your local area as a place to live? | Very dissatisfied | −0.15 | −0.95 to 0.65 | 1.89 | −0.49 to 4.27 | ||

| Fairly dissatisfied | 0.72 | 0.15 to 1.29 | 1.84 | 0.60 to 3.07 | |||

| Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied | 0.11 | −0.37 to 0.59 | −0.14 | −1.14 to 0.87 | |||

| Fairly satisfied | (ref) | (ref) | |||||

| Very satisfied | −0.46 | −0.73 to −0.19 | 0.12 | −0.57 to 0.81 | |||

| NC4. Most needs improving—access to affordable childcare | −0.31 | −0.56 to −0.07 | |||||

| NC21. Most needs improving—shopping facilities | −0.47 | −0.87 to −0.08 | −1.09 | −2.36 to 0.17 | |||

| NC22. Most needs improving—sports and leisure facilities | −1.27 | −2.29 to −0.26 | |||||

| NC25. Most needs improving—the level of traffic congestion | −0.26 | −0.51 to −0.01 | |||||

| NC26. Most needs improving—wage levels and the cost of living | 1.16 | 0.35 to 1.98 | |||||

| NC27. Do you agree or disagree that the council and the police are dealing with anti-social behaviour and crime issues that matter in your local area? | Very dissatisfied | 0.02 | −0.47 to 0.51 | 0.34 | −1.04 to 1.73 | ||

| Fairly dissatisfied | −0.09 | −0.43 to 0.24 | −0.41 | −1.57 to 0.75 | |||

| Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied | −0.39 | −0.69 to −0.09 | −1.49 | −2.52 to −0.46 | |||

| Fairly satisfied | (ref) | (ref) | |||||

| Very satisfied | 0.17 | −0.38 to 0.73 | −1.03 | −2.37 to 0.31 | |||

| NC28. How safe or unsafe do you feel when outside in your local area during the day? | Very unsafe | −1.46 | −2.86 to −0.07 | −2.81 | −5.66 to 0.05 | ||

| Fairly unsafe | −0.83 | −1.64 to −0.02 | −1.57 | −3.69 to 0.55 | |||

| Neither safe nor unsafe | −0.35 | −0.88 to 0.17 | 1.16 | −0.49 to 2.81 | |||

| Fairly safe | −0.26 | −0.53 to 0.02 | 0.46 | −0.63 to 1.54 | |||

| Very safe | (ref) | (ref) | |||||

| NC29. How safe or unsafe do you feel when outside in your local area after dark? | Very unsafe | 0.30 | −1.49 to 2.09 | ||||

| Fairly unsafe | −1.70 | −3.02 to −0.39 | |||||

| Neither safe nor unsafe | −1.04 | −2.38 to 0.30 | |||||

| Fairly safe | 0.29 | −0.93 to 1.52 | |||||

| Very safe | (ref) | ||||||

| NC30. In your local area, how much of a problem is—street drinking or drunken behaviour in public places? | A very big problem | −0.48 | −1.82 to 0.87 | ||||

| A fairly big problem | 1.16 | 0.08 to 2.23 | |||||

| Not a very big problem | −0.45 | −1.45 to 0.55 | |||||

| Not a problem at all | (ref) | ||||||

| NC32. In your local area, how much of a problem is—begging, vagrancy, or homeless people on the streets? | A very big problem | 0.13 | −0.90 to 1.17 | ||||

| A fairly big problem | −0.17 | −1.08 to 0.75 | |||||

| Not a very big problem | 0.96 | 0.22 to 1.69 | |||||

| Not a problem at all | (ref) | ||||||

| NC36. In your local area, how much of a problem is—loud music or other noise? | A very big problem | 0.74 | 0.12 to 1.36 | ||||

| A fairly big problem | 0.19 | −0.18 to 0.56 | |||||

| Not a very big problem | (ref) | ||||||

| Not a problem at all | 0.28 | −0.01 to 0.56 | |||||

| NC39. In your local area, how much of a problem is—out of control or dangerous dogs? | A very big problem | −2.52 | −4.38 to −0.67 | ||||

| A fairly big problem | −0.43 | −1.63 to 0.77 | |||||

| Not a very big problem | −0.56 | −1.23 to 0.11 | |||||

| Not a problem at all | (ref) | ||||||

| NC40. To what extent do you agree or disagree that your local area is a place where people from different backgrounds get on well together? | Strongly disagree | 0.67 | −0.42 to 1.76 | ||||

| Tend to disagree | 0.30 | −0.24 to 0.83 | |||||

| Neither agree nor disagree | −0.14 | −0.42 to 0.15 | |||||

| Tend to agree | (ref) | ||||||

| Strongly agree | 0.72 | 0.32 to 1.12 | |||||

| NC41. In your local area, how much of a problem do you think there is with people not treating each other with respect and consideration? | A very big problem | −0.70 | −1.55 to 0.15 | ||||

| A fairly big problem | −0.15 | −0.60 to 0.29 | |||||

| Not a very big problem | 0.47 | 0.17 to 0.76 | |||||

| Not a problem at all | (ref) | ||||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.4550 | 0.4901 | 0.5598 | ||||

References

- The Lancet. Global Burden of Disease. Available online: https://www.thelancet.com/lancet/visualisations/gbd-compare (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Dahlgren, G.; Whitehead, M. Policies and Strategies to Promote Social Equity in Health; Institute for Future Studies: Stockholm, Sweden, 2007; Available online: https://www.iffs.se/en/publications/working-papers/policies-and-strategies-to-promote-social-equity-in-health/ (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Marmot, M.; Allen, J.; Goldblatt, P.; Boyce, T.; McNeish, D.; Grady, M.; Geddes, I. Fair Society, Healthy Lives; The Marmot Review: London, UK, 2010; p. 238. Available online: http://www.instituteofhealthequity.org/resources-reports/fair-society-healthy-lives-the-marmot-review/fair-society-healthy-lives-full-report-pdf.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Sharpe, R.A.; Taylor, T.; Fleming, L.E.; Morrissey, K.; Morris, G.; Wigglesworth, R. Making the case for ‘whole system’ approaches: Integrating public health and housing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Capasso, L.; D’Alessandro, D. Housing and health: Here we go again. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, H.; Fernandez, R.; MacPhail, C. The social determinants of health and health outcomes among adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Public Health Nurs. 2021, 38, 942–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alidoust, S.; Huang, W. A decade of research on housing and health: A systematic literature review. Rev. Environ. Health 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickett, K.E.; Pearl, M. Multilevel analyses of neighbourhood socioeconomic context and health outcomes: A critical review. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2001, 55, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Durie, R.; Wyatt, K. New communities, new relations: The impact of community organization on health outcomes. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 65, 1928–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evaluation Group of Good Places Better Health. Good Places Better Health for Scotland’s Children; Scottish Government: Edinburgh, UK, 2011. Available online: https://www.argyll-bute.gov.uk/moderngov/documents/s63145/Good%20Places%20Better%20Health%20for%20Scotlands%20Children.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- WHO. Social Determinants of Mental Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241506809 (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Angel, S.; Gregory, J. Does housing tenure matter? Owner-occupation and wellbeing in Britain and Austria. Hous. Stud. 2021, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Baker, E.; Bentley, R. Understanding the mental health effects of instability in the private rental sector: A longitudinal analysis of a national cohort. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 296, 114778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonn, B.; Hawkins, B.; Rose, E.; Marincic, M. Income, housing and health: Poverty in the United States through the prism of residential energy efficiency programs. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 73, 101945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellaway, A.; Macdonald, L.; Kearns, A. Are housing tenure and car access still associated with health? A repeat cross-sectional study of UK adults over a 13-year period. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e012268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cairney, J.; Boyle, M.H. Home ownership, mortgages and psychological distress. Hous. Stud. 2004, 19, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollack, C.; von dem, K.O.; Siegrist, J. Housing and health in Germany. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2004, 58, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fenelon, A.; Mayne, P.; Simon, A.E.; Rossen, L.M.; Helms, V.; Lloyd, P.; Sperling, J.; Steffen, B.L. Housing assistance programs and adult health in the United States. Am. J. Public Health 2017, 107, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawder, R.; Walsh, D.; Kearns, A.; Livingston, M. Healthy mixing? Investigating the associations between neighbourhood housing tenure mix and health outcomes for urban residents. Urban Stud. 2013, 51, 264–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElroy, E.; Ashton, M.; Bagnall, A.M.; Comerford, T.; McKeown, M.; Patalay, P.; Pennington, A.; South, J.; Wilson, T.; Corcoran, R. The individual, place, and wellbeing–a network analysis. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department for Communities and Local Government. A Decent Home: Definition and Guidance for Implementation; Department for Communities and Local Government: London, UK, 2006. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/a-decent-home-definition-and-guidance (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Sodini, P.; Van Nieuwerburgh, S.; Vestman, R.; von Lilienfeld-Toal, U. Identifying the Benefits from Home Ownership: A Swedish Experiment; National Bureau of Economic Research: Paris, France, 2017; Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2785741 (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Hurst, E.; Stafford, F. Home is where the equity is: Mortgage refinancing and household consumption. J. Money Credit. Bank 2004, 36, 985–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Health England. Commissioning Cost-Effective Services for Promotion of Mental Health and Wellbeing and Prevention of Mental Ill-Health; Public Health England: London, UK, 2017. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/640714/Commissioning_effective_mental_health_prevention_report.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Wallace, A. Homeowners and Poverty: A Literature Review; Joseph Rowntree Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Available online: https://www.york.ac.uk/media/chp/Report.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Critchley, R.; Gilbertson, J.; Grimsley, M.; Green, G. Living in cold homes after heating improvements: Evidence from Warm-Front, England’s home energy efficiency scheme. Appl. Energy 2007, 84, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grey, C.N.B.; Jiang, S.; Nascimento, C.; Rodgers, S.E.; Johnson, R.; Lyons, R.A.; Poortinga, W. The short-term health and psychosocial impacts of domestic energy efficiency investments in low-income areas: A controlled before and after study. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sharpe, R.A.; Thornton, C.R.; Nikolaou, V.; Osborne, N.J. Higher energy efficient homes are associated with increased risk of doctor diagnosed asthma in a UK subpopulation. Environ. Int. 2015, 75, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, G.; Barton, A.; Basham, M.; Foy, C.; Eick, S.A.; Somerville, M. The Watcombe Housing Study: The short-term effect of improving housing conditions on the indoor environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2006, 361, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierse, N.; Carter, K.; Bierre, S.; Law, D.; Howden-Chapman, P. Examining the role of tenure, household crowding and housing affordability on psychological distress, using longitudinal data. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2016, 70, 961–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, W.; White, V.; Finney, A. Coping with low incomes and cold homes. Energy Policy 2012, 49, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnham, L.; Rolfe, S.; Anderson, I.; Seaman, P.; Godwin, J.; Donaldson, C. Intervening in the cycle of poverty, poor housing and poor health: The role of housing providers in enhancing tenants’ mental wellbeing. J. Hous Built Environ. 2022, 37, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolfe, S.; McKee, K.; Feather, J.; Simcock, T.; Hoolachan, J. The role of private landlords in making a rented house a home. Int. J. Hous. Policy 2022, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office for National Statistics. Estimates of the population for the UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/datasets/populationestimatesforukenglandandwalesscotlandandnorthernireland (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Cornwall Council. Cornwall: A Brief Description; Cornwall Council: Truro, UK, 2015. Available online: https://www.cornwall.gov.uk/media/1rch4i2o/cornwall-statistics-infographic-a3_proof3.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Transformation Cornwall. Cornwall Council Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) 2019 and 2015: Cornwall Reports. Available online: https://transformation-cornwall.org.uk/resources/cornwall-council-index-of-multiple-deprivation-imd-2019-and-2015-cornwall-reports (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Kosanic, A.; Harrison, S.; Anderson, K.; Kavcic, I. Present and historical climate variability in South West England. Clim. Change 2014, 124, 221–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornwall Council. Cornwall Council Residents’ Survey 2017 Full Report; Cornwall Council: Truro, UK, 2017. Available online: https://old.cornwall.gov.uk/media/28979484/cornwall-residents-survey-full-report-2017.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Cornwall.Gov.Uk. Residents’ Surveys. Available online: https://www.cornwall.gov.uk/council-and-democracy/have-your-say/residents-survey/ (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Cornwall Council. Localism and Devolution: A Fresh Approach; Cornwall Council: Truro, UK, 2015. Available online: https://www.cornwall.gov.uk/media/lj2ner0p/communities-devolution-offer-2015.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Ng Fat, L.; Scholes, S.; Boniface, S.; Mindell, J.; Stewart-Brown, S. Evaluating and establishing national norms for mental wellbeing using the short Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (SWEMWBS): Findings from the Health Survey for England. Qual. Life Res. 2017, 26, 1129–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stewart-Brown, S. The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scales-WEMWBS. Available online: https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/sci/med/research/platform/wemwbs (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Stewart-Brown, S.L.; Platt, S.; Tennant, A.; Maheswaran, H.; Parkinson, J.; Weich, S.; Tennant, R.; Taggart, F.; Clarke, A. The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS): A valid and reliable tool for measuring mental well-being in diverse populations and projects. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2011, 65, A38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- StataCorp Stata Statistical Software: Release 14; StataCorp LP: College Station, TX, USA, 2015.

- Sharpe, R.A.; Williams, A.J.; Simpson, B.; Finnegan, G.; Jones, T. A pilot study on the impact of a first-time central heating intervention on resident mental wellbeing. Indoor Built Environ. 2020, 31, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAneney, H.; Tully, M.A.; Hunter, R.F.; Kouvonen, A.; Veal, P.; Stevenson, M.; Kee, F. Individual factors and perceived community characteristics in relation to mental health and mental well-being. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- WHO. Mental Health: A State of Well-Being. Available online: http://www.who.int/features/factfiles/mental_health/en/ (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Sharpe, R.A.; Machray, K.E.; Fleming, L.E.; Taylor, T.; Henley, W.; Chenore, T.; Hutchcroft, I.; Taylor, J.; Heaviside, C.; Wheeler, B.W. Household energy efficiency and health: Area-level analysis of hospital admissions in England. Environ. Int. 2019, 133, 105164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, M.; Hearty, W.; Craig, P. The public health effects of interventions similar to basic income: A scoping review. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e165–e176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Healthwatch Cornwall. Cornwall Coronavirus Survey 2020: Full Report; Healthwatch Cornwall: Truro, UK, 2021; Available online: https://www.healthwatchcornwall.co.uk/sites/healthwatchcornwall.co.uk/files/Cornwall%20Coronavirus%20Survey%20-%20Full%20Report%20vFinal_0.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Healthwatch Cornwall. Accessing Mental Health Support in Cornwall; Healthwatch Cornwall: Truro, UK, 2021; Available online: https://www.healthwatchcornwall.co.uk/sites/healthwatchcornwall.co.uk/files/Accessing%20Mental%20Health%20Support%20in%20Cornwall%20report_0.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Zurek, M.; Friedmann, L.; Kempter, E.; Chaveiro, A.S.; Adedeji, A.; Metzner, F. Haushaltsklima, alleinleben und gesundheitsbezogene lebensqualität während des COVID-19-lockdowns in Deutschland. Prävention Gesundh. 2021, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikolai, J.; Keenan, K.; Kulu, H. Intersecting household-level health and socio-economic vulnerabilities and the COVID-19 crisis: An analysis from the UK. SSM Popul. Health 2020, 12, 100628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GOV.UK. Coronavirus and Depression in Adults, Great Britain: January to March 2021; GOV.UK: London, UK, 2021. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/wellbeing/articles/coronavirusanddepressioninadultsgreatbritain/januarytomarch2021 (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Leigh-Hunt, N.; Bagguley, D.; Bash, K.; Turner, V.; Turnbull, S.; Valtorta, N.; Caan, W. An overview of systematic reviews on the public health consequences of social isolation and loneliness. Public Health 2017, 152, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Smith, B.; Lim, M. How the COVID-19 pandemic is focusing attention on loneliness and social isolation. Public Health Res. Pract. 2020, 30, e3022008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjunath, J.; Manoj, N.; Alchalabi, T. Interventions against social isolation of older adults: A systematic review of existing literature and interventions. Geriatrics 2021, 6, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.; Kuhn, I.; McGrath, M.; Remes, O.; Cowan, A.; Duncan, F.; Baskin, C.; Oliver, E.J.; Osborn, D.P.J.; Dykxhoorn, J.; et al. A systematic scoping review of community-based interventions for the prevention of mental ill-health and the promotion of mental health in older adults in the UK. Health Soc. Care Community 2022, 30, 27–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamminen, N.; Kettunen, T.; Martelin, T.; Reinikainen, J.; Solin, P. Living alone and positive mental health: A systematic review. Syst. Rev. 2019, 8, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NHS. 5 Steps to Mental Wellbeing. Available online: https://www.nhs.uk/mental-health/self-help/guides-tools-and-activities/five-steps-to-mental-wellbeing/ (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Durie, R.; Wyatt, K. Connecting communities and complexity: A case study in creating the conditions for transformational change. Crit. Public Health 2013, 23, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Health England. Place-Based Approaches for Reducing Health Inequalities: Main Report; Public Health England: London, UK, 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-inequalities-place-based-approaches-to-reduce-inequalities/place-based-approaches-for-reducing-health-inequalities-main-report (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Health and Wellbeing Alliance. Evaluation of the New Voluntary, Community and Social Enterprise Health and Wellbeing Programme; GOV.UK: London, UK, 2021. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1024710/Evaluation-of-the-new-Voluntary-Community-and-Social-Enterprise-Health-and-Wellbeing-Programme-Health-and-Wellbeing-Alliance-report-accessible.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Charles, A.; Ewbank, L.; Naylor, C.; Walsh, N.; Murray, R. Developing Place-Based Partnerships: The Foundation of Effective Integrated Care Systems; The King’s Fund: London, UK, 2021; Available online: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/place-based-partnerships-integrated-care-systems (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Charles, A. Integrated Care Systems Explained: Making Sense of Systems, Places and Neighbourhoods; The King’s Fund: London, UK, 2021; Available online: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/integrated-care-systems-explained (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Barton, A.; Basham, M.; Foy, C.; Buckingham, K.; Somerville, M. The Watcombe Housing Study: The short term effect of improving housing conditions on the health of residents. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2007, 61, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Merlo, J.; Wagner, P.; Ghith, N.; Leckie, G. An original stepwise multilevel logistic regression analysis of discriminatory accuracy: The case of neighbourhoods and health. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0153778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sharpe, R.A.; Wyatt, K.M.; Williams, A.J. Do the Determinants of Mental Wellbeing Vary by Housing Tenure Status? Secondary Analysis of a 2017 Cross-Sectional Residents Survey in Cornwall, South West England. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3816. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19073816

Sharpe RA, Wyatt KM, Williams AJ. Do the Determinants of Mental Wellbeing Vary by Housing Tenure Status? Secondary Analysis of a 2017 Cross-Sectional Residents Survey in Cornwall, South West England. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(7):3816. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19073816

Chicago/Turabian StyleSharpe, Richard A., Katrina M. Wyatt, and Andrew James Williams. 2022. "Do the Determinants of Mental Wellbeing Vary by Housing Tenure Status? Secondary Analysis of a 2017 Cross-Sectional Residents Survey in Cornwall, South West England" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 7: 3816. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19073816

APA StyleSharpe, R. A., Wyatt, K. M., & Williams, A. J. (2022). Do the Determinants of Mental Wellbeing Vary by Housing Tenure Status? Secondary Analysis of a 2017 Cross-Sectional Residents Survey in Cornwall, South West England. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(7), 3816. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19073816