“There Was Some Kind of Energy Coming into My Heart”: Creating Safe Spaces for Sri Lankan Women and Girls to Enjoy the Wellbeing Benefits of the Ocean

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Safe Spaces for Females in the Sport-for-Development Context

1.2. Women’s Surfing and Gender Equity in Sri Lanka

1.3. Study Aim

- What factors enable females to participate in surfing programs?

- Which elements constitute a safe space?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Settings and Surfing Programs

2.2. Study Design and Data Collection

- Semi-structured interviews with 18 female surfers from the lead author’s Master’s thesis in 2017;

- Two expert interviews with founders of GMW and Kids Surf Club Meddawatta from the lead author’s Master’s thesis in 2017;

- Participatory observations during 40 swimming and surfing sessions (at GMW, the ABGSC, and SeaSisters) between 2017 and 2020;

- Participant evaluations of the SeaSisters program from 2019;

- Informal conversations with female participants between 2017 and 2020 (at GMW, the ABGSC, and SeaSisters);

- Two follow-up interviews with SeaSisters participants in 2020;

- Review and analysis of online videos documenting Sri Lankan female surfing (an overview of the videos is provided in Appendix A)

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Researcher Position

3. Results and Discussion

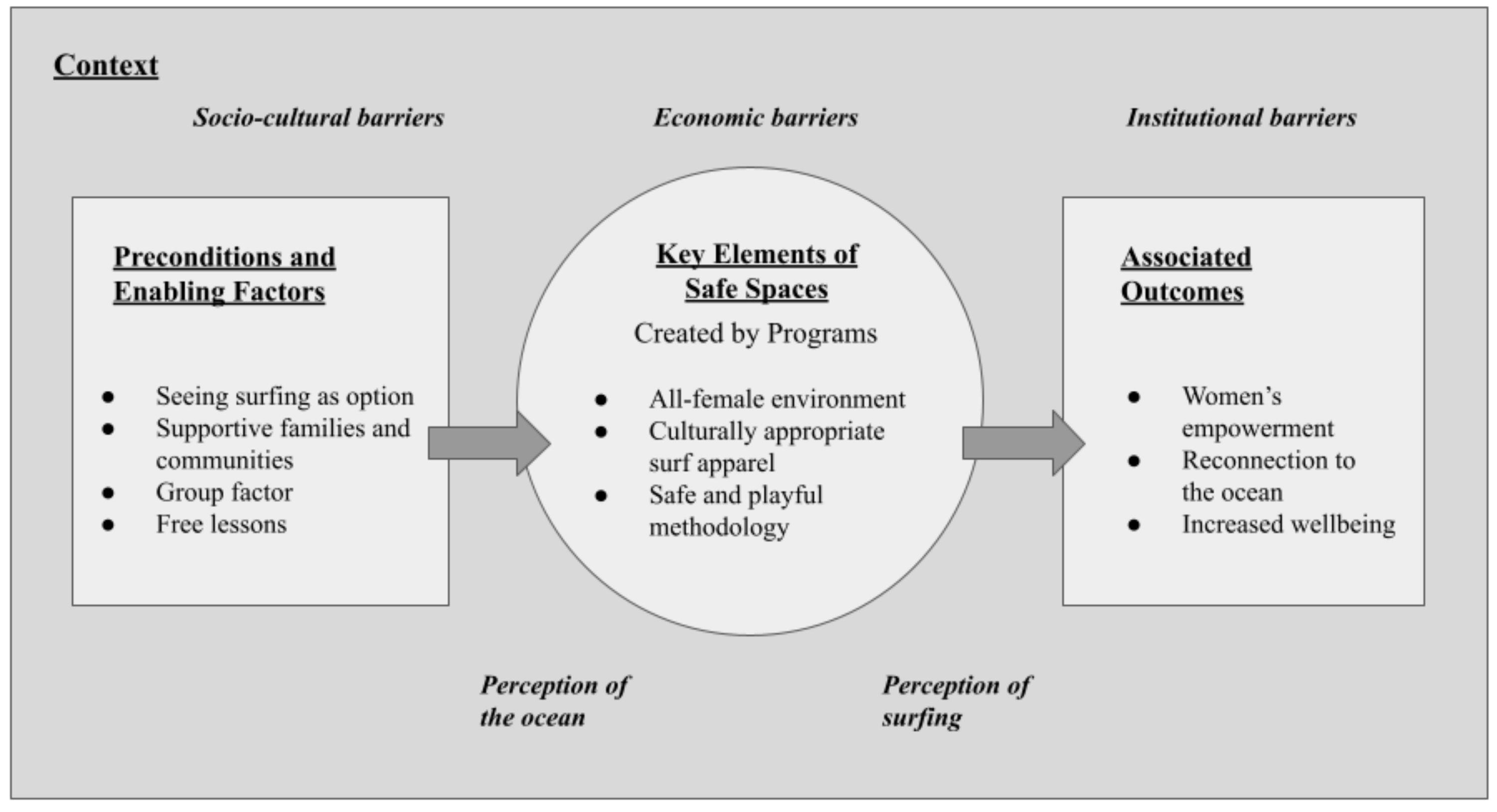

3.1. Context and Implications for Program Design

3.2. Preconditions and Enabling Factors

3.2.1. Seeing Surfing as an Option

3.2.2. Supportive Families

3.2.3. Supportive Communities

3.2.4. Group Factor

“Yeah, it will get better when like all the girls are bold and just go surfing and say, ‘We want to do this.’ It will start to change then. And then, people have no other choice than accepting it. […] the family will not talk about other girls because they have already one girl in their family who surfs.”Susanthika (21 years), interview in 2017.

3.2.5. Free Lessons

3.3. Key Elements of a Safe Space

3.3.1. All-Female Environment

3.3.2. Culturally Appropriate Surf Apparel

3.3.3. Safe and Playful Teaching Methodology

“Before, I was so afraid. When I started surfing, I learned things which made me so afraid, like standing on a board or paddling. This makes me more confident. This makes me less afraid of things.”Dayani (23 years), interview in 2017.

“Surfing makes me forget the tsunami. Now I want to have fun. Before, I was sad about the ocean. Now, I want more. I want to learn more. I want to surf more. Then I also forget my other things [worries] a little bit. Now, my energy is coming like, I want to learn. […] I want to catch my own wave.”Mona (31 years), interview in 2017.

3.4. Outcomes and Limitations

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Links to Videos Documenting Sri Lankan Female Surfing

References

- Thorpe, H.; Wheaton, B. The Olympic Games, Agenda 2020 and action sports: The promise, politics and performance of organisational change. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2019, 11, 465–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olive, R.; Roy, G.; Wheaton, B. Stories of Surfing: Surfing, space and subjectivity/intersectionality. In Surfing, Sex, Genders and Sexualities; Lisahunter, Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2018; pp. 148–167. [Google Scholar]

- lisahunter. Surfing, Sex, Genders and Sexualities; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Britton, E. ‘Be Like Water’. Reflections on Strategies Developing Cross-Cultural Programmes for Women, Surfing and Social Good. In The Palgrave Handbook of Feminism and Sport, Leisure and Physical Education; Mansfield, L., Caudwell, J., Wheaton, B., Watson, B., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2018; pp. 793–807. [Google Scholar]

- Burtscher, M. Women Making Waves—The Potential of Surfing for Women’s Empowerment: According to the Perspectives of Female Surfers from Sri Lanka. Master’s Thesis, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Guibert, C.; Arab, C. Being a female surfer in Morocco: The norms and social uses of the beach. Tour. Cult. Commun. 2017, 17, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knijnik, J.D.; Horton, P.; Cruz, L.O. Rhizomatic bodies, gendered waves: Transitional femininities in Brazilian Surf. Sport Soc. 2010, 13, 1170–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britton, E.; Olive, R.; Wheaton, B. Surfers and leisure. ‘Freedom’ to surf? Contested spaces on the coast. In Living with the Sea: Knowledge, Awareness and Action; Brown, M., Peters, K., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 147–166. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, J. In search of the postmodern surfer: Territory, terror and masculinity. In Some Like It Hot. The Beach as a Cultural Dimension; Skinner, J., Gilbert, K., Edwards, A., Eds.; Meyer and Meyer Sport: Oxford, UK, 2003; pp. 58–76. [Google Scholar]

- Olive, R. Women who surf: Female difference, intersecting subjectivities and cultural pedagogies. In The Pedagogies of Cultural Studies; Hickey, A., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 179–195. [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton, B. The Cultural Politics of Lifestyle Sports; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Reinhart, R.J. Majority Worldwide Cannot Swim; Most of Them Are Women. 2021. Available online: https://news.gallup.com/opinion/gallup/352679/majority-worldwide-cannot-swim-women.aspx (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- European Parliament. Report on Women, Gender Equality and Climate Justice (2017/2086(INI)). Committee on Women’s Rights and Gender Equality. 2017. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/A-8-2017-0403_EN.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- White, M.; Smith, A.; Humphryes, K.; Pahl, S.; Snelling, D.; Depledge, M. Blue Space: The importance of water for preference, affect, and restorativeness ratings of natural and built scenes. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 482–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olive, R.; Wheaton, B. Understanding blue spaces: Sport, bodies, wellbeing, and the sea. J. Sport Soc. Issues 2021, 45, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, J.; Kelly, P.; Niven, A. “When I Go There, I Feel Like I Can Be Myself.” Exploring Programme Theory within the Wave Project Surf Therapy Intervention. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marshall, J.; Kamuskay, S.; Samai, M.M.; Marah, I.; Tonkara, F.; Conteh, J.; Keita, S.; Jalloh, O.; Missalie, M.; Bangura, M.; et al. A Mixed Methods Exploration of Surf Therapy Piloted for Youth Well-Being in Post-Conflict Sierra Leone. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, J. A Global Exploration of Programme Theory within Surf Therapy. Ph.D. Thesis, Edinburgh Napier University, Edinburgh, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton, B. Surfing and Environmental Sustainability. In Sport and the Environment (Research in the Sociology of Sport); Wilson, B., Millington, B., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2020; Volume 13, pp. 157–178. [Google Scholar]

- Spaaij, R.; Schulenkorf, N. Cultivating Safe Space: Lessons for Sport for Development Projects and Events. J. Sport Manag. 2014, 28, 633–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, M. Creating Safe Spaces and Building Social Assets for Young Women in the Developing World: A New Role for Sports. Women’s Q. Stud. 2005, 33, 35–49. [Google Scholar]

- Salty Swamis. Surf History of Sri Lanka. Available online: https://www.saltyswamis.com/surf-history (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Herath, H.M.A. Place of Women in Sri Lankan Society: Measures for Their Empowerment for Development and Good Governance. Vidyodaya J. Manag. 2015, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Asian Development Bank; Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ). Country Gender Assessment Sri Lanka. An Update. 2015. Available online: https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/institutional-document/172710/sri-lanka-country-gender-assessment-update.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Nanayakkara, S. Trivialisation of Women’s Sport in Sri Lanka: Overcoming Invisible Barriers. Sri Lankan J. Humanit. 2011, XXXVII, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranasinghe, N. A New Perspective of Beach Boys and their Life Strategies in Tourism. Case Study of Hikkaduwa, Sri Lanka. St. Paulʼs Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 19, 61–70. [Google Scholar]

- Life Saving Association of Sri Lanka; Life Saving Victoria. Drowning Prevention Report Sri Lanka. 2014. Available online: https://de.scribd.com/document/251418871/Drowning-Prevention-Report-Sri-Lanka-2014 (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Sri Lankan Scientist Asha de Vos Earns Sea Hero Honors. 2020. Available online: https://www.scubadiving.com/sri-lankan-scientist-asha-de-vos-earns-sea-hero-honors (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Nishikiori, N.; Abe, T.; Costa, D.G.; Dharmaratne, S.; Kunii, O.; Moji, K. Who died as a result of the tsunami? Risk factors of mortality among internally displaced persons in Sri Lanka: A retrospective cohort analysis. BMC Public Health 2006, 6, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Parker-Jenkins, M. Problematising ethnography and case study: Reflections on using ethnographic techniques and researcher positioning. Ethnogr. Educ. 2018, 13, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britton, E.; O’Malley, S.; Hunt, S. Welcome Wave: Surf therapy in an unfamiliar sea for young asylum seekers. In Introducing Young People to ‘Unfamiliar Landscapes’; Smith, T.A., Dunkley, R.A., Pitt, H., Eds.; Palgrave: London, UK, 2022; p. XX. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, L.; Manion, L.; Morrison, K. Research Methods in Education, 7th ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Geertz, C. The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.; Strauss, A. Grounded theory: The discovery of grounded theory. Sociol. J. Br. Sociol. Assoc. 1967, 12, 27–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spivak, G.C. Can the subaltern speak? In Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture; Nelson, C., Grossberg, L., Eds.; Macmillan: London, UK, 1988; pp. 271–313. [Google Scholar]

- Mohanty, C.T. Under Western Eyes: Feminist Scholarship and Colonial Discourses. Boundary 2 1984, 12–13, 333–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englert, B.; Dannecker, P. Praktische und ethische Aspekte der Feldforschung. In Qualitative Methoden in der Entwicklungsforschung; Dannecker, P., Englert, B., Eds.; Mandelbaum: Vienna, Austria, 2014; pp. 233–265. [Google Scholar]

- Women Win. Creating a Safe Space. Available online: http://guides.womenwin.org/ig/safe-spaces/creating-a-safe-space (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- UN Women. Women, Gender Equality and Sport. 2007. Available online: http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/public/Women%20and%20Sport.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Cornwall, A.; Edwards, J. Feminisms, Empowerment and Development: Changing Women’s Lives; Zed Books: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rowlands, J. Questioning Empowerment: Working with Women in Honduras; Oxfam: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Britton, E. Just add surf: The power of surfing as a medium to challenge and transform gender inequalities. In Sustainable Stoke: Transitions to Sustainability in the Surfing World; Ponting, J., Borne, G., Eds.; University of Plymouth Press: Plymouth, UK, 2015; pp. 118–127. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, J. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Meier, M.; Saavedra, M. Esther Phiri and the Moutawakel effect in Zambia: An analysis of the use of female role models in sport-for-development. Sport Soc. 2009, 12, 1158–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeanes, R.; Magee, J. Promoting Gender Empowerment through Sport? Exploring the Experiences of Zambian Female Footballers. In Global Sport-for-Development: Critical Perspectives; Schulenkorf, N., Adair, D., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2014; pp. 133–154. [Google Scholar]

- Hooks, B. Sisterhood: Political Solidarity between Women. Fem. Rev. 1986, 23, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawansky, M.; Schlenker, M. Beyond girl power and the Girl Effect: The girling of sport for development and peace. In Beyond Sport for Development and Peace; Hayhurst, L., Kay, T., Chawansky, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 94–105. [Google Scholar]

- Sewall-Menon, J.; Bruce, J.; Austrian, K.; Brown, R.; Catino, J.; Colom, A.; Del Valle, A.; Demele, H.; Erulkar, A.; Hallman, K.; et al. The Cost of Reaching the Most Disadvantaged Girls: Programmatic Evidence from Egypt, Ethiopia, Guatemala, Kenya, South Africa, and Uganda; Population Council: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford, S. The social, cultural, and historical complexities that shape and constrain (gendered) space in an SDP organisation in Colombia. J. Sport Dev. 2017, 6, 60–70. [Google Scholar]

- Comley, C. “We have to establish our territory”: How women surfers ‘carve out’ gendered spaces within surfing. Sport Soc. 2016, 19, 1289–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenneis, V.; Agergaard, S.; Evans, A.B. Women-only swimming as a space of belonging. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2020, 14, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waves Wahines: How to Start a Nonprofit to Empower Girls through Surfing. 2020. Available online: https://www.surfpreneurs.club/blog/yevette-curtis-about-wave-wahines-and-how-to-start-a-nonprofit-to-empower-girls-through-surfing (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Brown Girl Surf. Available online: https://www.browngirlsurf.com/ (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- A Liquid Future. Girls Surfing Programme Sponsored by U.S. Embassy in Jakarta. 2016. Available online: https://aliquidfuture.com/girls-surfing-programme-sponsored-by-u-s-embassy-in-jakarta/ (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Hijas del Mar. Available online: https://hijasdelmar.com/about-us/ (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- De Vos, A. The Problem of ‘Colonial Science’. 2020. Available online: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-problem-of-colonial-science/ (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Ruttenberg, T.; Brosius, P. Decolonizing Sustainable Surf Tourism. In The Critical Surf Studies Reader; Hough-Snee, D.Z., Eastman, A.S., Eds.; Duke University Press: London, UK, 2017; pp. 109–134. [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton, B.; Waiti, J.; Cosgriff, M.; Burrows, L. Coastal blue space and wellbeing research: Looking beyond western tides. Leis. Stud. 2020, 39, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnell, S.; Hayhurst, L. De-Colonising the Politics and Practice of Sport-for-Development: Critical Insights from Post-Colonial Feminist Theory and Methods. In Global Sport-for-Development: Critical Perspectives; Schulenkorf, N., Adair, D., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2013; pp. 33–61. [Google Scholar]

- Nanayakkara, S. Crossing Boundaries and Changing Identities: Empowering South Asian Women through Sport and Physical Activities. Int. J. Hist. Sport 2012, 29, 1885–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, P.R.; Subish, P. Fair skin in South Asia: An obsession? J. Pak. Assoc. Dermatol. 2007, 17, 100–104. [Google Scholar]

- Britton, E.; Foley, R. Sensing Water: Uncovering Health and Well-Being in the Sea and Surf. J. Sport Soc. Issues 2020, 45, 60–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britton, E.; Kindermann, G.; Domegan, C.; Carlin, C. Blue care: A systematic review of blue space interventions for health and wellbeing. Health Promot. Int. 2020, 35, 50–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taylor, J. Giving kids a break: How surfing has helped young people in Cornwall overcome mental health and social difficulties. Mental Health Incl. 2013, 17, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glassman, L.; Otis, N.; Michalewicz-Kragh, B.; Walter, K. Gender Differences in Psychological Outcomes Following Surf Therapy Sessions among U.S. Service Members. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfister, G.; Hartmann-Tews, I. Women and sport in comparative and international perspectives. Issues, aims and theoretical approaches. In Sport and Women: Social Issues in International Perspective; Pfister, G., Hartmann-Tews, I., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2003; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

| Barriers | Mediators |

|---|---|

| Do not see surfing as a possibility for them; cannot identify with Western surfer girls | Seeing surfing as an option through external interventions and local role models |

| Need permission of families to participate in activities outside the home; they have concerns regarding safety and reputation; gendered constraints on time | Support of families through building trust and creating a space that is considered safe and culturally acceptable |

| Resistance and harassment of local community members and visitors | Supportive communities; changing perceptions of appropriate roles for females |

| Restricted mobility; expectation not to go surfing alone | Group factor |

| Prioritization of survival needs; expensive surf lessons and equipment | Free lessons, provision of equipment |

| Expectation not to mix with men after reaching puberty; women do not feel safe with unknown men | All-female environment (participants and instructors) |

| Gender norms and expectations around clothing and beauty (modesty, fair skin) | Culturally appropriate surf apparel |

| Ocean regarded as a dangerous place; women cannot swim; trauma from 2004 tsunami | High safety standards; playful approach; skill-building |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Burtscher, M.; Britton, E. “There Was Some Kind of Energy Coming into My Heart”: Creating Safe Spaces for Sri Lankan Women and Girls to Enjoy the Wellbeing Benefits of the Ocean. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3342. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063342

Burtscher M, Britton E. “There Was Some Kind of Energy Coming into My Heart”: Creating Safe Spaces for Sri Lankan Women and Girls to Enjoy the Wellbeing Benefits of the Ocean. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(6):3342. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063342

Chicago/Turabian StyleBurtscher, Martina, and Easkey Britton. 2022. "“There Was Some Kind of Energy Coming into My Heart”: Creating Safe Spaces for Sri Lankan Women and Girls to Enjoy the Wellbeing Benefits of the Ocean" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 6: 3342. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063342

APA StyleBurtscher, M., & Britton, E. (2022). “There Was Some Kind of Energy Coming into My Heart”: Creating Safe Spaces for Sri Lankan Women and Girls to Enjoy the Wellbeing Benefits of the Ocean. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(6), 3342. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063342