Abstract

A decrease in the working-age population in aging societies causes a shortage of employees in workplaces due to long-term care (LTC) leave for family and relatives as well as longer working hours or overwork among those remaining in the workplace. We collected and analyzed literature and guidelines regarding social-support policies on LTC in workplaces in seven countries (Canada, France, Germany, Japan, Sweden, the UK, and the USA) to propose an effective way of occupational health support for those in need. Our analysis indicated the existence of a system that incorporates the public-assistance mechanism of providing unused paid leave to those in need. Additionally, recipients of informal care provided by employees tended to expand to non-family members under the current occupational health system. On the other hand, the health management of employees as informal caregivers remained neglected. Likewise, salary compensation and financial support for LTC-related leave need to be improved. In order to monitor and evaluate the progress and achievement of current legal occupational health systems and programs related to the social support of LTC among employees, the available national and/or state-based quantitative data should be comparable at the international level.

1. Introduction

The demand for long-term care (LTC) has been increasing recently in aging societies. A proportion of the total population aged 65 and over among the countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has increased from 13.0% to 17.5% over the last two decades since 2000 [1]. The number of people receiving LTC at home among 15 OECD countries in 2010–2019 has also increased by 72% [1]. On the other hand, the working-age population has declined from 66.2% to 64.8% in 2000–2020, indicating that the old-age dependency ratio or people aged 65 or above relative to those aged 15–64 (ODR) has risen from 19.4% to 27.0% [1]. If this trend continues, the ODR is estimated to reach 38.7% in 2040 and 45.2% in 2060, and it is already close to 50% in some countries such as Japan (48.9%) [1].

Under such circumstances, the demand for LTC by the working-age population as informal caregivers is likely to increase further in the future. Particularly, informal caregivers are preferably accepted in many countries and regions, possibly due to lack of accessible formal LTC facilities, poor quality of LTC, and traditional model of intergenerational and familial relations [2,3,4]. Thus, LTC policies and legislation have been developed and amended according to the latest situation of LTC in each country. In Europe, regionwide conferences explored challenges and good practices in informal long-term care provision based on the latest LTC policies and legislation [5]. In Japan, the Child and Family Care Leave Law has been revised periodically to promote support for balancing work and family care [6]. Nonetheless, necessary supports for employees engaged in LTC as informal caregivers have not been well directed as part of occupational health. A recent interview among working caregivers indicated that there was a lack of mutual understanding of LTC between employers and caregivers, resulting in inadequate workplace supports, which are essential to satisfy the needs of working caregivers in different stages of LTC [7]. Providing informal care while being employed requires a balance between the care-dependent person and the workplace responsibilities of the caregiver [8]. In fact, a large number of employees engaged in informal face difficulties in managing their daily work and family and relative care, including the limitation of their working hours or drop-out of their current work [3,4,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. Conversely, work performance can also be affected by caregiving, resulting in fewer promotions and a less-demanding job in the workplace [17]. It is frequently reported that women, in particular, seem to be more affected by the balance between both LTC and work restrictions [2,10,11,13,15,18]. They are often at risk of economic deprivation [13,15,19]. The poor in particular tend to be reluctant to use formal care for financial reasons [20]. The hidden cost of informal care is not well discussed, and a report indicates that it is twice as expensive as formal care [20]. A large number of informal caregivers also suffer from unfavorable physical and/or mental health conditions due to their responsibilities of caregiving and other life events such as job and/or household work [15,16,17,21]. Experiencing work interference or a change in work status due to caregiving is also associated with greater emotional stress [22]. Hence, the need for respite, wishing for a break, and balancing work and care have been discussed elsewhere [8,20,23,24,25,26,27]. On the other hand, generally low awareness of the legal LTC support system prevents employees from making proper use of existing supports [2,12,13,15,28]. There is also a disparity in the use of the LTC support system depending on the region of residence. Informal caregivers living in rural areas are reported to have more limited access to the company’s system of care than those living in urban areas [29]. Even if they are able to take leave, there are cases where they are reluctant to use the system itself due to company culture or social stigma [13]. However, supportive organizations were more likely to ensure caregivers’ work performance and to maintain low stress at work [26,30]. On the national level, gaps between existing needs and available supports are reported [27]. Additionally, countries providing extensive health and LTC support systems are more likely to report minimal negative effects on work than countries with limited support [17].

As described above, there are still many improvements that need to be made in the system for the protection of workers in the occupational health field who are caring for family members or relatives, and there is ample room to consider how to continue to effectively support them as informal caregivers. Therefore, we compared and examined the current occupational health policies and regulations regarding the LTC support for employees, and proposed how both the government and companies should provide a better working environment for those in need of LTC. Particularly, we evaluated the current policy and regulation of LTC among workforces in selected countries using the existing literature to address how we formulate a better occupational health environment for them.

2. Materials and Methods

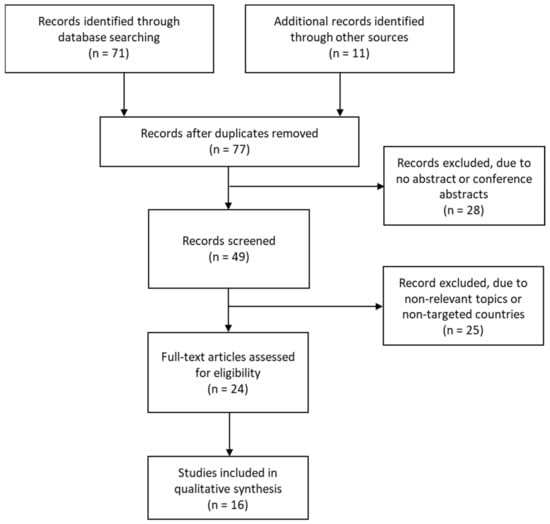

This study examined the social support for workers in need of LTC for family members and its current status in different countries, using existing policy documents and data. Seven OECD-member countries were selected: Canada, France, Germany, Japan, Sweden, the United Kingdom, (UK), and the United States of America (USA). The policy documents that related to occupational health and LTC were obtained from each government’s website and academic journals in search engines, such as Pubmed, Scopus, and Europe PMC. The following keywords were selected to identify the articles: informal caregiver, long-term care, policy, workplace. Moreover, we utilized the latest edition of the Overseas Situation Report published by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan, which overviewed the health and labor policies, and their recent trends, in selected countries, including the above seven nations except for Japan [31]. Then, the selected documents were screened according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [32]. As a result, a total of 16 articles were selected for the analysis (Figure 1). On the other hand, as quantitative figures, we extracted related data on occupational health and LTC from the websites of UN agencies and international organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO), International Labour Organization (ILO), and OECD to depict the current situation of social support systems.

Figure 1.

Document-screening process.

The analysis was based on the following two topics. First, as “Social support for work–life balance focusing on LTC, based on occupational health standards and LTC-related laws and guidelines”, we summarized the basic rules and regulations related to occupational health in each country and their history in reaching the currently available LTC support in terms of the legal system. The second topic is “A detail of LTC support systems for employees who take care of family members, including shorter working hours, paid or unpaid leave, and financial compensation”. We overviewed each country’s specific rules to protect employees in various situations towards LTC for their family and relatives, such as shorter working hours and restrictions on late-night work as well as LTC-leave systems and salary compensation for leave. The extent to which these systems are recognized and utilized was assessed through available official data published in each country.

3. Results

3.1. Basic Information and Occupational Health Standards in Each Country

Table 1 shows the demographic information and occupational health standards of seven countries. The working-age population was found to decline in all countries between 2005–2020. Accordingly, the old-age dependency ratio, the number of people in 15–64 years of age supporting for a person aged 65 years and above, exceeded 0.25 in 2020. Particularly, Japan has almost reached 0.5, meaning that one elderly person is supported by only two working-age people. In all countries, it is projected that less than three persons will support one elderly person by 2040. Now, life expectancy at birth is over 80 years old except in the USA, while the gap between life expectancy and healthy life expectancy now extends to more than 10 years. This indicates that those who are over 70 years of age find it more difficult to live independently and are more likely to receive any sort of care in their daily life.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic indicators among seven countries.

Table 2 shows the working conditions and trends for workers in the seven countries of study [31,33,34,35,36,37]. The legal working hours are 8 h per day in Canada, Germany, and Japan, and 40 h per week in Canada, Japan, and Sweden. The USA also has a 40 h week, but only for federal employees and in several states. The OECD statistics showed that the average weekly working hours did not exceed 40 h in any country, although France slightly exceeded the legal working hours. On the other hand, in Canada, Sweden, and the UK, overtime working hours are limited to 48 h per week, including legal working hours, with Sweden averaging 7 days and the UK averaging 17 weeks. In France and Germany, employees can work up to 10 h per day, including legal working hours, within 48 h per week and 44 h per week on average for 12 weeks in France, and within 10 h per day on average for 24 weeks in Germany. Japan allows for overtime of up to 45 h per month and up to 360 h per year. According to OECD statistics, the proportion of employees working more than 49 h per week ranged from 5.9 to 18.3%, with Japan (18.3%) and the United States (14.2%) having the highest. Surcharges for overtime work are covered in Canada, France, Japan, and the USA. In Germany and Sweden, the surcharges may be allowed through a labor-management agreement. The UK has no such provision. With the exception of the USA, rest periods, holidays, and annual leave are legislated in all of the studied countries. In particular, annual leave is allowed for up to 20–30 days per year, depending on the length of service in a company. In France, there is an obligation of taking leaves of 12–24 consecutive working days between May 1 and October 31 every year, and similar provisions exist in Germany and Sweden. There is a system that allows unused leave to be carried over to the following year or later in some countries. It is allowed, if the extension is justified in Germany, for a one-year extension in Japan and five years in Sweden in case of leaves exceeding 20 days. In addition, Sweden allows companies to buy back 25 or more days of leave if they do not use it. As for other working conditions for general workers, flexible working time systems are allowed in France, Germany, Japan, the UK, and the USA under certain conditions, and restrictions on late-night work are in place in France, Japan, Sweden, and the UK.

Table 2.

Occupational health regulations among seven countries.

3.2. LTC Support Systems for Employees Who Take Care of Family Members and Relatives, by Country

Table 3 depicts the support systems for employees related to LTC among seven countries [8,11,13,15,16,28,31,35,36,38,39,40,41,42]. It included laws related to LTC leave and LTC insurance system, and LTC leaves and allowance designated for employees. We summarized the current situations of LTC support systems by country below.

Table 3.

Supports for employees of those in need of nursing or long-term care (LTC) in seven countries.

3.2.1. Canada

In Canada, under the Employment Insurance Act, compassionate care leave is available for up to 28 weeks per year for workers with a dying family member, and up to 17 weeks for workers with a family member with a serious medical condition. For workers with family members with serious medical conditions, there is a form of leave related to critical illness of up to 17 weeks (up to 37 weeks for children under 18). Since both are unpaid leaves, Caregiving Benefits and Family Caregiver benefits have been established to provide financial support to workers. Under the former, those who have worked at least 600 h in the past 52 weeks and whose income has been reduced by at least 40% per week due to the terminal care of a family member such as a child, parent, or sibling, are entitled to one week of compassionate care benefits. After a waiting period, 55% of the average weekly wage for the insured period (up to $547 per week) will be paid for up to 26 weeks. The latter benefit provides up to 15 weeks of leave to care for a seriously ill family member (up to 35 weeks if the seriously ill family member is under the age of 18). In both cases, full-time work is not permitted while receiving the benefits.

3.2.2. France

In France, the labor law stipulates the content of the current system. In addition to the conventional system of leave for relatives, there is a system of leave for close relatives (Congé de procheaidant) that includes those who regularly and frequently assist in daily life. There are no benefits associated with nursing care leave for employees, but the employer may not refuse the request for leave and must guarantee the same position after returning to work as before the period of leave. There is also a family solidarity leave (Congé de solidarité familiale) of up to three months to care for a terminally ill relative, which can be renewed once. The annual leave donation system has been brought into effect recently. It is the one that, upon agreement with the employer, a colleague in the same company can anonymously donate unused paid leave to a worker who has a seriously ill or disabled person needing care. If this system is applied, the worker’s salary is maintained during the leave period, and the leave period is calculated as actual working hours to determine the length of service. In addition, seniors aged 60 and above are entitled to receive self-help benefits for the elderly, including home and institutional services.

3.2.3. Germany

In Germany, the Nursing Care Hours Act (Pflegezeitgesetz), enacted in 2008, the Family Care Hours Act (Familienpflegezeitgesetz), enacted in 2012, and the Law for a Better Harmonization of Family, Nursing Care and Work (Gesetz zur besseren Vereinbarkeit von Familie, Pflege und Beruf) guarantees workers’ rights. For example, in the case of an urgent need to provide nursing care, workers can use the short-term leave system for up to 10 days, and 90% of their previous wage (take-home pay) (with an upper limit) is paid as a nursing-care support allowance. In addition, in companies with 16 or more employees, they can take full or partial leave of absence for up to six months as part of the nursing care time system, and companies with 26 or more employees that require longer-term care can request a reduction in working hours to a minimum of 15 h per week and a maximum of 24 months (family care time system). These care hour programs are unpaid but interest-free loan programs are available. Demands of respite among informal caregivers have yet to be achieved with legal guidelines.

3.2.4. Japan

In Japan, the Child Care and Family Care Leave Law stipulates a leave system and benefits for nursing care. The law guarantees the right to take a total of three nursing care leave days within a total of 93 days per family member, and also allows nursing care workers to take up to five days of nursing care leave per year (10 days per year for two or more family members) in one-day or half-day units. In addition, if the worker providing nursing care makes a request, overtime work can be restricted, with restrictions on overtime work exceeding 24 h per month and 150 h per year, as well as restrictions on late-night work between 10:00 p.m. and 5:00 a.m. Additionally, for workers who provide nursing care as a measure for shorter working hours, they are obliged to take one of the following measures, which can be used at least twice in three years: (1) shorter working hours system, (2) flextime system, (3) earlier or later start and end times, and (4) measures to assist with nursing care expenses.

3.2.5. Sweden

In Sweden, the law on family care leave (Lagomledighet för närståendevård, 1988:1465) provides up to 100 days of leave per caregiver as family care (end-of-life care) leave. This system allows up to 100 days of leave per family member to be taken as family care (end-of-life care) leave, although the leave cannot be taken by more than one person at the same time. During the leave, a family care (end-of-life care) allowance is provided.

3.2.6. The UK

In the UK, the Work and Families Act, The Care Act, and The Equal Act provide for care, but there is no system for care leave covering a period of longer than one or two months. To compensate for this, a time-off system for family members in emergencies and a flexible working system is applied, which allows employees to be excused from work or change their working conditions for a reasonable period without an expiration date. In such cases, caregiver allowances and national insurance caregiver exemptions can be used as salary guarantees, although there are income restrictions and other requirements for receiving such benefits.

3.2.7. The USA

The Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) offers up to 12 weeks of unpaid leave in 12 months for childbirth, childcare, family nursing/LTC, and personal medical treatment. FLMA protects employees’ jobs, but there are several limitations such as no payment during leaves and organizational eligibility requirements. Its compensations are critical and several states including California and New York are implementing, at the state level, paid family leave. The Older Americans Act is a federal law that provides subsidies for long-term care services that do not fall under the category of medical care, but its budget is extremely small and there is basically no public long-term care insurance system. Medicare, which is included in the medical care category, and Medicaid, for those who can no longer afford to pay for their care, are the only means of coverage.

4. Discussion

In this study, we analyzed and evaluated the different LTC systems for employees engaged in informal caregiving in seven countries. While all countries must manage with an aging society involving the decline in the working-age population, informal care by employees is still a major mode of LTC for family members and close relatives. This is due to the fact that informal care usually targets people who are close to the employees and is perceived as a cost-effective method, as well as the high cost of the service provided by care facilities which are often insufficient in terms of both quantity and quality [2,3]. In addition, the socio-cultural norms in the regions lead women to engage in caregiving more often, and therefore female workers tend to limit their work and dedicate themselves to informal care [11]. However, the occupational health regulations and standards regarding LTC are not necessarily as comprehensive as those of childcare and are still being revised in response to changes in social conditions.

By conducting an extensive policy review, it has been found that occupational supports for employees involved in LTC as informal caregivers are relatively progressive in several countries. After several region-wide discussions and legislative amendments, these countries have established a unique system tailored to national circumstances. Particularly, it is notable that there is a system to effectively utilize mutual aid among employees. In France, unused paid leave by colleagues in a company can be donated to workers anonymously for LTC and seriously ill cases, upon agreement with the employer [35]. Although paid leave is not necessarily taken for the sole purpose of LTC, it is one of the most useful and practical means for employees engaged in LTC. In the USA, a maximum of 12-week unpaid leave is guaranteed by the federal Family and Medical Leave Act, but the Paid Family Leave system is being implemented at the state level [13,16,27]. On the other hand, many countries have set time limits for using paid leave. Although there are no international statistics available on annual leave usage, it can be assumed that there is a certain level of unused leave among employees. In Japan, the annual leave usage rate per worker in 2020 was 56.6%, and nearly half of leave remained unused [43]. This figure is the highest ever recorded since the survey began, and a lot of unused leave is abandoned since the carryover of the unused leave is only one year. There are reports that it is difficult to take leave due to socio-cultural norms and an unfavorable atmosphere [13]. In the USA, a large number of people are unaware of the state-based paid leave program itself [13,27]. It is, therefore, essential to establish a solid legal system for both workers and employers to foster a healthy working environment as an occupational health measure.

Recently, a discussion on how far to extend the number of care recipients covered by employees as informal care has been in motion. Until now, the range of informal care provided by employees has been considered as only to family members and relatives in many countries. In Sweden, however, there is a system in which the eligibility for LTC leave is not limited to family members or close relatives. Sweden has the lowest number of people per family among OECD countries, at 1.80 in 2015 [44]. The average number of family members in other countries is also declining, especially in urban areas, where this number is smaller than in rural areas. Additionally, it is not always the case that caregivers live near the family and relatives who are in need of LTC [29]. Under these circumstances, the entire community should protect those who need care, regardless of whether they are family members or not. In addition, from the perspective of improving the working environment for employees who take on the role of caregivers before and/or after work, there is a need to develop systems that allow them to continue to work flexibly while they can provide LTC when needed, as with childbirth and childcare-related systems. For example, in the UK, a system that allows employees to leave work for an appropriate period in case of an emergency, not limited to LTC care, and a flextime system have been established [38]. Although there is no current LTC leave system for 1–2 months in the UK, discrimination and harassment due to LTC are prohibited [38]. In Japan, labor regulations for employees who require LTC are mentioned in the same law as for childbirth and childcare, and other than temporary leave limited to LTC, there are the same provisions as normal working conditions such as shorter working hours, prohibition of late-night work, etc. [6]. Unlike childbirth and childcare, however, it is often unpredictable when LTC will occur due to types of illnesses such as cerebrovascular diseases; therefore it is not easy to make timely preparations for care in advance. For this reason, each country should continue to develop and flexibly implement relevant laws and regulations over the next 20 to 30 years so that employees can deal with LTC issues without being disadvantaged.

On the other hand, salary compensation and financial support for LTC-related leave are limited in all countries. A public survey revealed that more than half of respondents mentioned earning money as the main purpose of work, followed by finding a purpose in life or fulfilling one’s duties as a member of society [45]. In terms of the ideal job, many people cited a stable income, and many also wanted a job in which they were able to maintain their work–life balance [45]. In other words, the greatest threat is the negative impact on their daily lives financially so that they desire to avoid the loss of income due to LTC as much as possible. For this reason, it is necessary to enhance the safety net as a society, not only by the efforts of one company. In some countries, such systems are already in place. For example, in France, deductions for medical expenses are permitted, and in Germany, interest-free loans are available. In Japan, there is a system to compensate two-thirds of the salary for a certain period from employment insurance for those who take LTC-related leaves. Financial security is also of great concern in the USA, where only unpaid leaves are guaranteed under federal law, so the state-level supports are currently under-implemented in several states [27]. In Canada, also, tax-relief programs for informal caregivers are available at the state level, but they are usually scarcely known of and do little to support low-income caregivers [15]. Therefore, since LTC-related leaves and partial leaves are often unpaid in many countries, there is a need to further improve the system so that employees can engage in LTC without such stress.

Lastly, but not least, the health issues of the employees themselves who provide informal care are critical from the perspective of occupational health. The importance of respite care as protection for informal caregivers has been discussed elsewhere [8,20,23,24,25,26,27]. However, our study revealed that no country has legislated self-care for workers who are responsible for informal care. In the field of occupational health, health disorders are mostly related to compensation for illness and accidents during work and do not include matters outside of working hours. However, informal care is provided outside of working hours, and many health problems have been reported as a result of engaging in informal care, which may affect regular work [22]. These issues are more complex to resolve due to the need to consider one’s socioeconomic factors [16,17]. Protecting the health of employees as an occupational health policy will lead to corporate profits and social development, and protect a healthy work–life balance among them. Therefore, it would be valuable if respite care for employees who are engaged in LTC as informal caregivers were provided by each company or legislated for by the national government.

A limitation of the study is that it was difficult to provide quantitative data on the actual implementation of LTC-related leave and absence systems in the selected countries. This is due to the fact that there are almost no statistics available for international comparisons. Although data are released at the state and/or national levels [16,46,47], the level of data is far comparable at this moment. Only a few studies have shown such results [48]. Thus, even if an innovative system is proposed, it is not possible to evaluate the extent to which it is being utilized at this moment. However, in order to monitor and evaluate the impact of each system, such statistics should be regularly reported in every country and internationally comparable for a better implementation of the systems.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we overviewed the LTC-related social support policies and systems for employees serving as informal caregivers in seven countries as part of occupational health measures. As a result, we found that various systems are in operation, taking into account the circumstances of each country. As the working-age population decreases, a system that incorporates the public assistance mechanism of providing unused paid leave to those in need will provide facilitate the more flexible operation of the existing occupational health system. Expanding the eligibility for LTC leave to non-family members will also be an asset for both employees and local communities in need of nursing care. In contrast, the health management of employees as informal caregivers is critical as part of occupational health measures, but progress made in this area is relatively scarce. It is strongly recommended that legislation and related programs be put in place to secure employee health conditions. Likewise, salary compensation and financial support for LTC-related leave should be better strengthened. Finally, it is essential to monitor and evaluate the progress and achievement of current legal systems and programs related to the social support of LTC among employees. So far, it has been difficult to quantify the extent to which employees engaged in informal caregiving benefited from the current policies and regulations as occupational health measures. These gaps should be further researched.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.K. and H.S.; methodology, K.K. and H.S.; formal analysis, K.K.; investigation, K.K.; resources, K.K. and H.S.; data curation, K.K.; writing—original draft preparation, K.K.; writing—review and editing, H.S. and T.Y.; visualization, K.K.; supervision, T.Y.; project administration, K.K. and H.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) Statistics. Available online: https://stats.oecd.org/ (accessed on 9 December 2021).

- Spasova, S.; Baeten, R.; Coster, S.; Ghailani, D.; Peña-Casas, R.; Vanhercke, B. Challenges in Long-Term Care in Europe: A Study of National Policies, 2018; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=20225&langId=en (accessed on 6 December 2021).

- European Commission; Directorate-General for Employment; Social Affairs and Inclusion; Zigante, V. Informal Care in Europe: Exploring Formalisation, Availability and Quality; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018; Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/96d27995-6dee-11e8-9483-01aa75ed71a1 (accessed on 9 December 2021).

- The Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training (JIPAT). JIPAT Research Report No. 204: Combining Work and Care under the Re-Familization of Elderly Care in Japan; JIPAT: Tokyo, Japan, 2020; Available online: https://www.jil.go.jp/english/reports/jilpt_research/2020/no.204.html (accessed on 25 January 2022).

- European Commission. Executive Summary: Peer Review on ‘Work-Life Balance: Promoting Gender Equality in Informal Long-Term Care Provision; European Commission: Brussels, Germany, 2020; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=23272&langId=en (accessed on 6 December 2021).

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW). Annual Health, Labour and Welfare Report—The Social Security System and People’s Work Styles in the Reiwa Era; MHLW: Tokyo, Japan, 2020; Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/wp/wp-hw13/index.html (accessed on 25 January 2022).

- Vos, E.E.; de Bruin, S.R.; van der Beek, A.J.; Proper, K.I. “It’s Like Juggling, Constantly Trying to Keep All Balls in the Air": A Qualitative Study of the Support Needs of Working Caregivers Taking Care of Older Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plöthner, M.; Schmidt, K.; de Jong, L.; Zeidler, J.; Damm, K. Needs and preferences of informal caregivers regarding outpatient care for the elderly: A systematic literature review. BMC Geriatr. 2019, 19, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, F.; Rodrigues, R. Informal Carers: Who Takes Care of Them? Policy Brief 2010, 4, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Bureau of Japan. 2017 Employment Status Survey: Summary of the Results; Statistics Bureau of Japan: Tokyo, Japan, 2017; Available online: https://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/shugyou/pdf/sum2017.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- ICF. Peer Review on “Work-Life Balance: Promoting Gender Equality in Informal Long-Term Care Provision”; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?langId=en&catId=1024&furtherNews=yes&newsId=9841 (accessed on 6 December 2021).

- The Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training (JIPAT). Survey on Family Care and Employment; JIPAT: Tokyo, Japan, 2020; Available online: https://www.jil.go.jp/institute/research/2020/documents/0200.pdf (accessed on 26 May 2020).

- Feinberg, L.F. Paid Family Leave: An Emerging Benefit for Employed Family Caregivers of Older Adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 1336–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenfield, J.C.; Hasche, L.; Bell, L.M.; Johnson, H. Exploring how workplace and social policies relate to caregivers’ financial strain. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 2018, 61, 849–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stall, N. We should care more about caregivers. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2019, 191, E245–E246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- U.S. Department of Labor. Navigating the Demands of Work and Eldercare; U.S. Department of Labor: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. Available online: https://ecommons.cornell.edu/handle/1813/78429 (accessed on 25 January 2022).

- Schulz, R.; Beach, S.R.; Czaja, S.J.; Martire, L.M.; Monin, J.K. Family Caregiving for Older Adults. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2020, 71, 635–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabinet Office. Annual Report on the Ageing Society 2021; Cabinet Office: Tokyo, Japan, 2021; Available online: https://www8.cao.go.jp/kourei/whitepaper/index-w.html (accessed on 19 January 2022).

- Meyer, K.; Rath, L.; Gassoumis, Z.; Kaiser, N.; Wilber, K. What Are Strategies to Advance Policies Supporting Family Caregivers? Promising Approaches From a Statewide Task Force. J. Aging Soc. Policy 2018, 31, 66–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paraponaris, A.; Davin, B.; Verger, P. Formal and informal care for disabled elderly living in the community: An appraisal of French care composition and costs. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2011, 13, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Detaille, S.I.; de Lange, A.; Engels, J.; Pijnappels, M.; Hutting, N.; Osagie, E.; Reig-Botella, A. Supporting Double Duty Caregiving and Good Employment Practices in Health Care Within an Aging Society. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 535353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longacre, M.L.; Valdmanis, V.G.; Handorf, E.A.; Fang, C.Y. Work Impact and Emotional Stress Among Informal Caregivers for Older Adults. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2016, 72, 522–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCaffrey, N.; Gill, L.; Kaambwa, B.; Cameron, I.D.; Patterson, J.; Crotty, M.; Ratcliffe, J. Important features of home-based support services for older Australians and their informal carers. Health Soc. Care Community 2015, 23, 654–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Eldh, A.C.; Carlsson, E. Seeking a balance between employment and the care of an ageing parent. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2010, 25, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCann, S.; Evans, D. Informal care: The views of people receiving care. Health Soc. Care Community 2002, 10, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plaisier, I.; van Groenou, M.B.; Keuzenkamp, S. Combining work and informal care: The importance of caring organisations. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2014, 25, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meyer, K.; Kaiser, N.; Benton, D.; Fitzpatrick, S.; Gassoumis, Z.; Wilber, K.; The California Task Force on Family Caregiving. Picking up the Pace of Change for California’s Family Caregivers: A Report from the California Task Force on Family Caregiving; USC Leonard Davis School of Gerontology: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018; Available online: http://tffc.usc.edu/2018/07/02/final-report-from-the-california-task-force-on-family-caregiving-2/ (accessed on 25 January 2022).

- Le Bihan, B. ESPN Thematic Report on Challenges in Long-Term Care: France; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=19847&langId=en (accessed on 6 December 2021).

- Henning-Smith, C.; Lahr, M. Rural-Urban Difference in Workplace Supports and Impacts for Employed Caregivers. J. Rural Health 2019, 35, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Groenou, M.I.B.; De Boer, A. Providing informal care in a changing society. Eur. J. Ageing 2016, 13, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW). Overseas Situation Report 2019; MHLW: Tokyo, Japan, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. The Prisma Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- The Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training (JIPAT). Databook of International Labour Statistics 2019; JIPAT: Tokyo, Japan, 2019; Available online: https://www.jil.go.jp/english/estatis/databook/2019/index.html (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- Employment and Social Development Canada. Hours of Work. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/programs/employment-standards/work-hours.html (accessed on 24 January 2022).

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW). Overseas Situation Report 2018; MHLW: Tokyo, Japan, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- The Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training (JIPAT). Childcare Leave Systems and Other Policies to Support Balancing Work and Childcare in Other Countries: Sweden, France, Germany, the United Kingdom, the United States, and South Korea; JIPAT: Tokyo, Japan, 2018; Available online: https://www.jil.go.jp/institute/siryo/2018/197.html (accessed on 28 May 2020).

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW). Overseas Situation Report 2020; MHLW: Tokyo, Japan, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- The Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training (JIPAT). Childcare and Family Care Leave Systems in Europe; JIPAT: Tokyo, Japan, 2017; Available online: https://www.jil.go.jp/institute/siryo/2017/186.html (accessed on 28 May 2020).

- Social Protection Committee (SPC); European Commission (DG EMPL). 2021 Long-Term Care Report—Trends, Challenges and Opportunities in an Ageing Society: Country Profiles, Volume II; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlinger, T. ESPN Thematic Report on Challenges in Long-Term Care: Germany; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=19848&langId=en (accessed on 6 December 2021).

- Schön, P.; Heap, J. ESPN Thematic Report on Challenges in Long-Term Care: Sweden; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=19870&langId=en (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW). 2018 Edition Annual Health, Labour and Welfare Report -Achieve a Society in which Everyone Can Play an Active Role while Coping with Disabilities, Illnesses or Other Hardships; MHLW: Tokyo, Japan, 2018; Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/wp/wp-hw12/dl/summary.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2022).

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW). General Survey on Working Conditions 2020; MHLW: Tokyo, Japan, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). OECD Family Database; OECD: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cabinet Office. Opinion Poll on People’s Life; Cabinet Office: Tokyo, Japan, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Statistical Bureau of Japan. 2017 Employment Status Survey; Statistical Bureau of Japan: Tokyo, Japan, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Glendinning, C. ESPN Thematic Report on Challenges in Long-Term Care: United Kingdom; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=19873&langId=en (accessed on 6 December 2021).

- Tur-Sinai, A.; Teti, A.; Rommel, A.; Hlebec, V.; Yghemonos, S.; Lamura, G. Cross-national data on informal caregivers of older people with long-term care needs in the European population: Time for a more coordinated and comparable approach. J. Biosoc. Sci. 2022, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).