Community Participation and Subjective Well-Being of Older Adults: The Roles of Sense of Community and Neuroticism

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Community Participation and Sense of Community

1.2. Sense of Community and Subjective Well-Being (SWB)

1.3. Neuroticism

1.4. Theoretical Basis

1.5. Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Instruments

2.2.1. Community Participation Questionnaire

2.2.2. Sense of Community Scale

2.2.3. Neuroticism

2.2.4. Subjective Well Being

2.2.5. The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS)

2.2.6. Positive Affect and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS)

2.2.7. The Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CES-D) Scale

2.2.8. Covariates

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Findings

3.2. Correlation Analyses

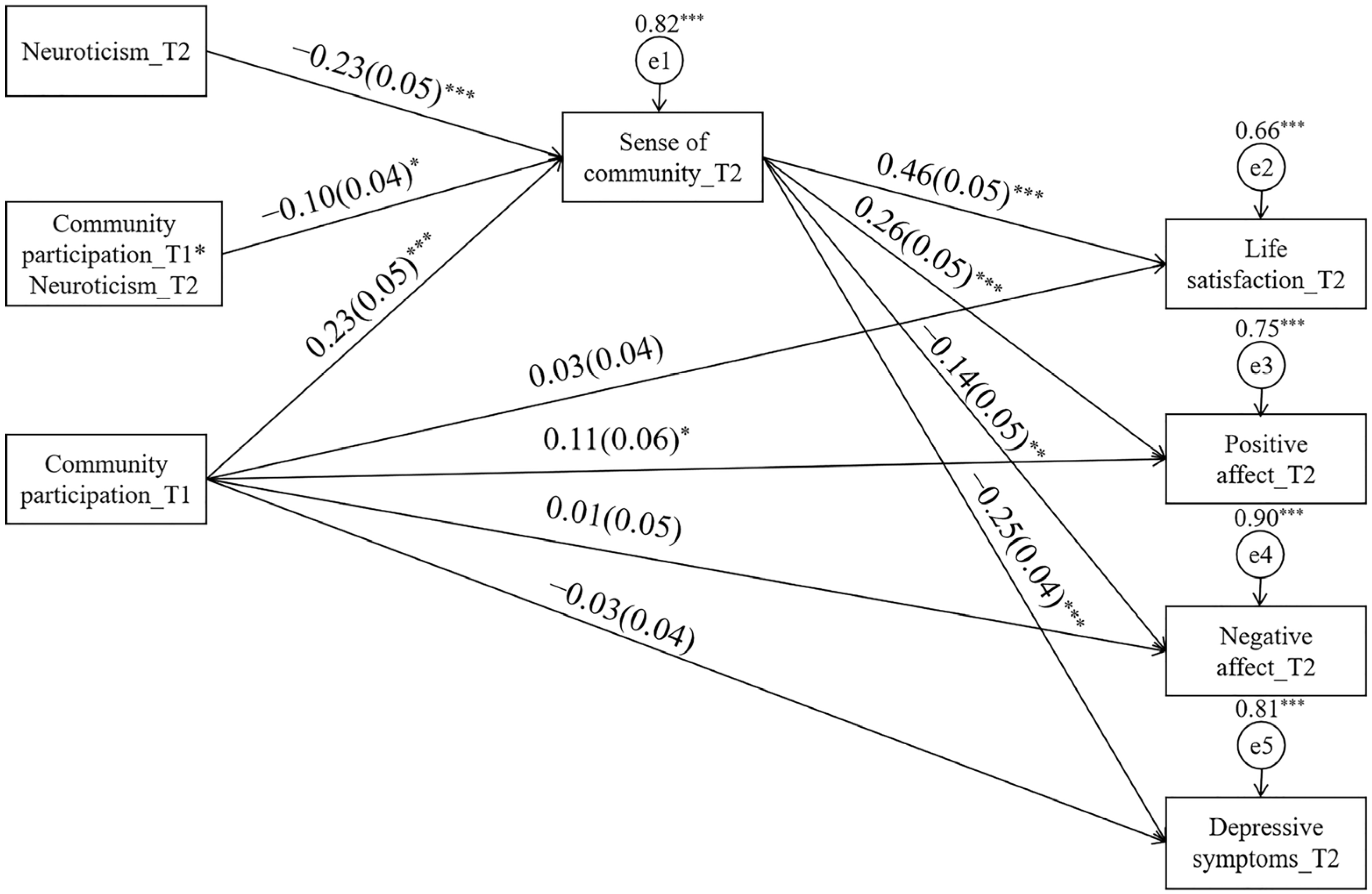

3.3. Structure Equation Model

4. Discussion

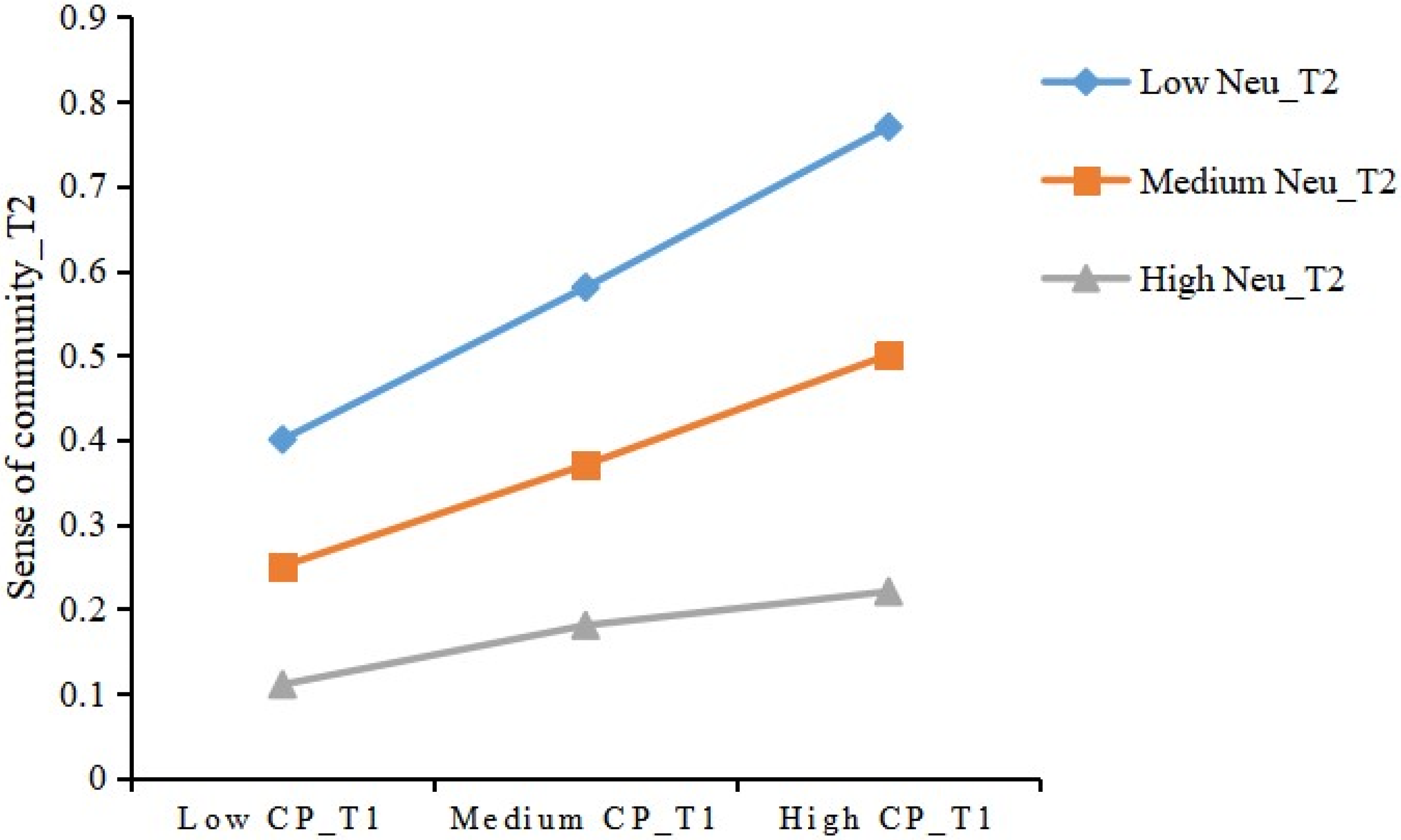

4.1. Community Participation, Sense of Community and Neuroticism

4.2. Theoretical and Practical Significance

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Antonucci, T.C.; Fiori, K.L.; Birditt, K.; Jackey, L.M.H. Convoys of Social Relations: Integrating Life-Span and Life-Course Perspectives. In The Handbook of Life-Span Development; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 434–473. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, R.L.; Antonucci, T.C. Convoys over the life course: Attachment, roles, and social support. In Life-Span, Development, and Behavior; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1980; pp. 254–283. [Google Scholar]

- Serrat, R.; Scharf, T.; Villar, F.; Gómez, C. Fifty-Five Years of Research into Older People’s Civic Participation: Recent Trends, Future Directions. Gerontologits 2019, 60, e38–e51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- United Nations. Madrid International Plan of Action on Ageing; United Nations: Madrid, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. Available online: http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/zxfb/202105/t20210510_1817181.html (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Liu, L.-J.; Guo, Q. Life satisfaction in a sample of empty-nest elderly: A survey in the rural area of a mountainous county in China. Qual. Life Res. 2008, 17, 823–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J. Social Participation and Subjective Well-Being Among Retirees in China. Soc. Indic. Res. 2015, 123, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilleard, C.; Hyde, M.; Higgs, P. The Impact of Age, Place, Aging in Place, and Attachment to Place on the Well-Being of the Over 50 s in England. Res. Aging 2007, 29, 590–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iecovich, E. Aging in place: From theory to practice. Anthropol. Noteb. 2014, 20, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Talò, C.; Mannarini, T.; Rochira, A. Sense of Community and Community Participation: A Meta-Analytic Review. Soc. Indic. Res. 2014, 117, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, Z. Community Participation and Subjective Wellbeing: Mediating Roles of Basic Psychological Needs among Chinese Retirees. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 743897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, N. Church-Based Volunteering, Providing Informal Support at Church, and Self-Rated Health in Late Life. J. Aging Health 2009, 21, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, C.; Jiang, S.; Li, N.; Zhang, Q. Influence of social participation on life satisfaction and depression among Chinese elderly: Social support as a mediator. J. Community Psychol. 2018, 46, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilkington, P.D.; Windsor, T.; Crisp, D. Volunteering and Subjective Well-Being in Midlife and Older Adults: The Role of Supportive Social Networks. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2012, 67, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Piliavin, J.A.; Siegl, E. Health Benefits of Volunteering in the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2007, 48, 450–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Z. Outdoor group activity, depression, and subjective well-being among retirees of China: The mediating role of meaning in life. J. Heal. Psychol. 2017, 24, 1245–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albanesi, C.; Cicognani, E.; Zani, B. Sense of community, civic engagement and social well-being in Italian adolescents. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 17, 387–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, D.; Friedman, Y. Postforced eviction communities: The contribution of personal and environmental resources to the sense of belonging to the community. J. Community Psychol. 2019, 47, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lounsbury, J.W.; Loveland, J.M.; Gibson, L.W. An investigation of psychological sense of community in relation to Big Five personality traits. J. Community Psychol. 2003, 31, 531–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarason, S.B. Community psychology, networks, and Mr. Everyman. Am. Psychol. 1976, 31, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, D.W.; Chavis, D.M. Sense of community: A definition and theory. J. Community Psychol. 1986, 14, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughey, J.; Speer, P.W.; Peterson, N.A. Sense of community in community organizations: Structure and evidence of validity. J. Community Psychol. 1999, 27, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, D.A.; Perkins, D.D. Confirmatory factor analysis of the Sense of Community Index and development of a Brief SCI. J. Community Psychol. 2003, 31, 279–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavis, D.M.; Wandersman, A. Sense of community in the urban environment: A catalyst for participation and community development. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1990, 18, 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, C.R.; Dietz, R.D.; Feinberg, S.L. The Paradox of Social Organization: Networks, Collective Efficacy, and Violent Crime in Urban Neighborhoods. Soc. Forces 2004, 83, 503–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicognani, E.; Pirini, C.; Keyes, C.; Joshanloo, M.; Rostami, R.; Nosratabadi, M. Social Participation, Sense of Community and Social Well Being: A Study on American, Italian and Iranian University Students. Soc. Indic. Res. 2007, 89, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.; Chi, I.; Dong, X. The Relationship of Social Engagement and Social Support with Sense of Community. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2017, 72, S102–S107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, N.A.; Speer, P.W.; Hughey, J.; Armstead, T.L.; Schneider, J.E.; Sheffer, M.A. Community organizations and sense of community: Further development in theory and measurement. J. Community Psychol. 2008, 36, 798–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prati, G.; Albanesi, C.; Pietrantoni, L. The Reciprocal Relationship between Sense of Community and Social Well-Being: A Cross-Lagged Panel Analysis. Soc. Indic. Res. 2016, 127, 1321–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prezza, M.; Amici, M.; Roberti, T.; Tedeschi, G. Sense of community referred to the whole town: Its relations with neighboring, loneliness, life satisfaction, and area of residence. J. Community Psychol. 2001, 29, 29–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, K.; Townley, G. How Far Have we Come? An Integrative Review of the Current Literature on Sense of Community and Well-being. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2020, 66, 166–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J. Perceived residential environment of neighborhood and subjective well-being among the elderly in China: A mediating role of sense of community. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 51, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ahern, J.; Galea, S. Collective Efficacy and Major Depression in Urban Neighborhoods. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2011, 173, 1453–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, E.S.; Chen, Y.; Kawachi, I.; VanderWeele, T.J. Perceived neighborhood social cohesion and subsequent health and well-being in older adults: An outcome-wide longitudinal approach. Heal. Place 2020, 66, 102420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eysenck, H.J.; Eysenck, M.W. Personality and Individual Differences: A Natural Science Approach; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Gunthert, K.C.; Cohen, L.H.; Armeli, S. The role of neuroticism in daily stress and coping. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 77, 1087–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suls, J.; Martin, R. The Daily Life of the Garden-Variety Neurotic: Reactivity, Stressor Exposure, Mood Spillover, and Maladaptive Coping. J. Pers. 2005, 73, 1485–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parisi, J.M. Determinants and effects of engagement in adulthood (Publication No. AAT 3301209). Diss. Abstr. Int. 2007, 69B, 155. [Google Scholar]

- van Leeuwen, C.M.; Post, M.W.; Westers, P.; van der Woude, L.H.; de Groot, S.; Sluis, T.; Slootman, H.; Lindeman, E. Relationships Between Activities, Participation, Personal Factors, Mental Health, and Life Satisfaction in Persons with Spinal Cord Injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2012, 93, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claridge, G.; Davis, C. What’s the use of neuroticism? Pers. Individ. Differ. 2001, 31, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijk, V.; Cramm, J.M.; Nieboer, A.P. Social cohesion as perceived by community-dwelling older people: The role of individual and neighborhood characteristics. Int. J. Ageing Later Life 2014, 8, 9–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Itzhaky, H.; Zanbar, L.; Levy, D.; Schwartz, C. The Contribution of Personal and Community Resources to Well-Being and Sense of Belonging to the Community among Community Activists. Br. J. Soc. Work 2013, 45, 1678–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, D. Individual and Community Factors Affecting Psychological Sense of Community, Attraction, and Neighboring in Rural Communities. Can. Rev. Sociol. 2008, 45, 305–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, M.M.; Esenaliev, D.; Brück, T.; Boehnke, K. The connection between social cohesion and personality: A multilevel study in the Kyrgyz Republic. Int. J. Psychol. 2020, 55, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Monroe, S.M.; Simons, A.D. Diathesis-stress theories in the context of life stress research: Implications for the depressive disorders. Psychol. Bull. 1991, 110, 406–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollrath, M. Personality and stress. Scand. J. Psychol. 2001, 42, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, Y.; Fornara, F.; Manca, S.; Bonnes, M.; Bonaiuto, M. Perceived Residential Environment Quality Indicators and neighborhood attachment: A confirmation study on a Chinese sample in Chongqing. Psych. J. 2015, 4, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomaszewski, W. Living Environment, Social Participation and Wellbeing in Older Age: The Relevance of Housing and Local Area Disadvantage. J. Popul. Ageing 2013, 6, 119–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suls, J.; Martin, R.; David, J.P. Person-Environment Fit and its Limits: Agreeableness, Neuroticism, and Emotional Reactivity to Interpersonal Conflict. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1998, 24, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Q.; Bai, S.; Dan, Q.; Lei, L.; Wang, P. Mother phubbing and adolescent academic burnout: The mediating role of mental health and the moderating role of agreeableness and neuroticism. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2020, 155, 109622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, E. Development and Validation of an International English Big-Five Mini-Markers. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2008, 45, 542–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, Y.; Huang, Y.G. Measuring community social capital: An empirical study. Sociol. Stud. 2008, 23, 122–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachman, M.E.; Weaver, S.L. The Midlife Development Inventory (MIDI) Personality Scales: Scale Construction and Scoring. Available online: http://www.brandeis.edu/departments/psych/lachman/pdfs/midi-personality-scales.pdf (accessed on 26 May 2021).

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The Satisfaction with Life Scale. J. Pers. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.-T.; Chan, A.C.M. Filial Piety and Psychological Well-Being in Well Older Chinese. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2006, 61, P262–P269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.-T.; Li, K.-K.; Leung, E.M.F.; Chan, A.C.M. Social Exchanges and Subjective Well-being: Do Sources of Positive and Negative Exchanges Matter? J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2011, 66, 708–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bai, X.; Wu, C.H.; Zheng, R.; Ren, X. The Psychometric Evaluation of the Satisfaction with Life Scale Using a Nationally Representative Sample of China. J. Happiness Stud. 2011, 12, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.; Zhu, D. Subjective Well-Being of Chinese Landless Peasants in Relatively Developed Regions: Measurement Using PANAS and SWLS. Soc. Indic. Res. 2015, 123, 817–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kercher, K. Assessing Subjective Well-Being in the Old-Old. Res. Aging 1992, 14, 131–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radloff, L.S. The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1977, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.; Sun, X.; Strauss, J.; Zhang, P.; Zhao, Y. Depressive symptoms and SES among the mid-aged and elderly in China: Evidence from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study national baseline. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 120, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User’s Guide, 8th ed.; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. Specification, evaluation, and interpretation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 8–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.W.; Wen, Z.; Hau, K.-T. Structural Equation Models of Latent Interactions: Evaluation of Alternative Estimation Strategies and Indicator Construction. Psychol. Methods 2004, 9, 275–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, N.S.; Jang, Y.; Lee, B.S.; Haley, W.; Chiriboga, D.A. The Mediating Role of Loneliness in the Relation between Social Engagement and Depressive Symptoms among Older Korean Americans: Do Men and Women Differ? J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2013, 68, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zimmerman, M.A.; Rappaport, J. Citizen participation, perceived control, and psychological empowerment. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1988, 16, 725–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughey, J.; Peterson, N.A.; Lowe, J.; Oprescu, F. Empowerment and Sense of Community: Clarifying Their Relationship in Community Organizations. Heal. Educ. Behav. 2006, 35, 651–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughey, J.; Speer, P.W. Community, sense of community, and networks. In Psychological Sense of Community: Research, Applications, and Implications; Fisher, A.T., Sonn, C.C., Bishop, B.J., Eds.; Kluwer Academic/Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 69–88. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, N. Social Capital: A Theory of Social Structure and Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, P.A. Gender, social engagement, and limitations in late life. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 73, 1428–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness; The Guilford Press: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrand, C.; Martinent, G. Need frustration and depressive symptoms in French older people: Using a self-determination approach. Aging Ment. Health 2021, 25, 1094–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrick, M.R.; Stewart, G.L.; Neubert, M.J.; Mount, M.K. Relating member ability and personality to work-team processes and team effectiveness. J. Appl. Psychol. 1998, 83, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, D.A.; Maxwell, S.E. Testing Mediational Models with Longitudinal Data: Questions and Tips in the Use of Structural Equation Modeling. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2003, 112, 558–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Preacher, K.J. Advances in Mediation Analysis: A Survey and Synthesis of New Developments. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2015, 66, 825–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rook, K.S. Social networks in later life: Weighing positive and negative effects on health and well-being. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 24, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Variable | n | Valid % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 149 | 32.04 |

| Female | 316 | 67.96 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 65~69 | 290 | 62.37 |

| 70~74 | 134 | 28.82 |

| 75~79 | 32 | 6.88 |

| 80 and over | 9 | 1.94 |

| Educational level | ||

| Junior high school and lower | 58 | 12.47 |

| Senior high school | 112 | 24.09 |

| Junior college | 170 | 36.56 |

| Bachelor degree or above | 125 | 26.88 |

| Spouse status | ||

| Without a spouse | 78 | 16.77 |

| With a spouse | 387 | 83.23 |

| Monthly income (CNY) | ||

| Less than 2000 | 28 | 6.02 |

| 2000~4000 | 158 | 33.98 |

| 4000~6000 | 99 | 21.29 |

| 6000~8000 | 58 | 12.47 |

| More than 8000 | 122 | 26.24 |

| Physical condition | ||

| Poor | 10 | 2.15 |

| Fair | 211 | 45.38 |

| Good | 207 | 44.52 |

| Excellent | 37 | 7.96 |

| M(SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Age | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 2 Sex | 0.01 | 1 | |||||||||||

| 3 Educational level | 0.04 | −0.26 *** | 1 | ||||||||||

| 4 Marital status | 0.13 ** | 0.11 * | −0.01 | 1 | |||||||||

| 5 Monthly income | 0.13 ** | −0.14 ** | 0.37 *** | 0.04 | 1 | ||||||||

| 6 Physical condition | −0.02 | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 1 | |||||||

| 7 Community participation_T1 | 20.36(0.64) | −0.02 | 0.05 | −0.02 | −0.05 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 1 | |||||

| 8 Neuroticism_T2 | 20.54(0.64) | −0.05 | −0.01 | −0.10 * | −0.03 | −0.15 ** | −0.30 *** | −0.14 ** | 1 | ||||

| 9 Sense of community_T2 | 30.69(0.63) | 0.01 | 0.13 ** | −0.04 | −0.06 | 0.04 | 0.26 *** | 0.28 *** | −0.30 *** | 1 | |||

| 10 Life satisfaction_T2 | 30.76(0.69) | 0.06 | 0.13 ** | 0.07 | −0.09 * | 0.16 ** | 0.28 *** | 0.18 *** | −0.41 *** | 0.57 *** | 1 | ||

| 11 Positive affect_T2 | 30.46(0.65) | 0.02 | 0.09 * | 0.13 ** | −0.05 | 0.06 | 0.42 *** | 0.20 *** | −0.53 *** | 0.45 *** | 0.54 *** | 1 | |

| 12 Negative affect_T2 | 10.54(0.50) | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.04 | −0.01 | −0.33 *** | −0.05 | 0.57 *** | −0.31 *** | −0.44 *** | −0.45 *** | 1 |

| 13 Depressive symptoms_T2 | 0.77(0.53) | −0.02 | −0.05 | −0.06 | 0.05 | −0.05 | −0.39 *** | −0.12 * | 0.59 *** | −0.43 *** | −0.51 *** | −0.65 *** | 0.75 *** |

| β | Se | t | p | Effect Size | LLCL | ULCL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| From CP_T1 to LS_T2 | |||||||

| Total effect | 0.14 | 0.04 | 3.33 | 0.001 | 0.05 | 0.22 | |

| Direct effect | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.40 | 0.687 | 13.33% | −0.06 | 0.09 |

| Indirect effect | 0.13 | 0.03 | 4.80 | 0.000 | 86.67% | 0.08 | 0.18 |

| From CP_T1 to PA_T2 | |||||||

| Total effect | 0.16 | 0.05 | 3.02 | 0.003 | 0.06 | 0.27 | |

| Direct effect | 0.08 | 0.05 | 1.49 | 0.135 | 47.06% | −0.02 | 0.18 |

| Indirect effect | 0.09 | 0.02 | 4.40 | 0.000 | 52.94% | 0.05 | 0.13 |

| From CP_T1 to NA_T2 | |||||||

| Total effect | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.33 | 0.744 | −0.10 | 0.07 | |

| Direct effect | 0.05 | 0.04 | 1.16 | 0.248 | 45.45% | −0.03 | 0.13 |

| Indirect effect | −0.06 | 0.02 | −3.81 | 0.000 | 54.55% | −0.10 | −0.03 |

| From CP_T1 to DEP_T2 | |||||||

| Total effect | −0.08 | 0.04 | −1.80 | 0.073 | −0.17 | 0.03 | |

| Direct effect | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.21 | 0.834 | 10.00% | −0.08 | 0.09 |

| Indirect effect | −0.09 | 0.02 | −4.73 | 0.000 | 90.00% | −0.13 | −0.06 |

| Three Levels of Neuroticism | β | Se | t | p | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M − 1SD | 0.33 | 0.06 | 5.65 | 0.000 | 0.21 | 0.43 |

| M | 0.22 | 0.05 | 4.82 | 0.008 | 0.13 | 0.31 |

| M + 1SD | 0.12 | 0.07 | 1.78 | 0.074 | −0.02 | 0.24 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, L.; Zhang, Z. Community Participation and Subjective Well-Being of Older Adults: The Roles of Sense of Community and Neuroticism. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3261. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063261

Chen L, Zhang Z. Community Participation and Subjective Well-Being of Older Adults: The Roles of Sense of Community and Neuroticism. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(6):3261. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063261

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Lanshuang, and Zhen Zhang. 2022. "Community Participation and Subjective Well-Being of Older Adults: The Roles of Sense of Community and Neuroticism" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 6: 3261. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063261

APA StyleChen, L., & Zhang, Z. (2022). Community Participation and Subjective Well-Being of Older Adults: The Roles of Sense of Community and Neuroticism. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(6), 3261. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063261