A Single-Case Design Investigation for Measuring the Efficacy of Gestalt Therapy to Treat Depression in Older Adults with Dementia in Italy and in Mexico: A Research Protocol

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Dementia as a Social Disease: The Impact of Dementia on Informal Carers’ Health and Social Life

1.2. The Contest of Dementia Diagnosis and Formal Care: A Snapshot of Italy and Mexico

1.3. Psychological Support and Psychotherapy Interventions: Gestalt Therapy View on Dementia and on Depression

1.4. Selection of the Research Design: Single-Case Experimental Design

1.5. Proposed Research Aims and Objectives

- -

- To assess if there is a pre/post improvement and, if so, how great this is (clinical significance), according to the outcome variables rates, as well as whether it can be attributed to the therapy intervention.

- -

- To assess if study participants suffer with loneliness.

- -

- To assess if loneliness is mitigated by the regular contact with the therapist.

- -

- To assess if the regular contact with the therapist affects the level of depression.

- -

- To assess if a clinical improvement of depression symptoms has an indirect effect on the level of family carers’ burden.

- -

- To assess if a clinical improvement has an indirect effect on the mutuality of the relationship between the patient and the family carer.

- Is there any pre/post treatment improvement?

- If the answer to question 1 is yes, is the change clinically significant (reduction of symptoms by 50%)?

- If loneliness is a factor, is the improvement solely due to the social contact with the therapist? OR

- Can the improvement be attributed to the therapy intervention?

- Can the improvement of the patient also have an impact on the caregiver’s burden and level of mutuality?

2. Materials and Methods

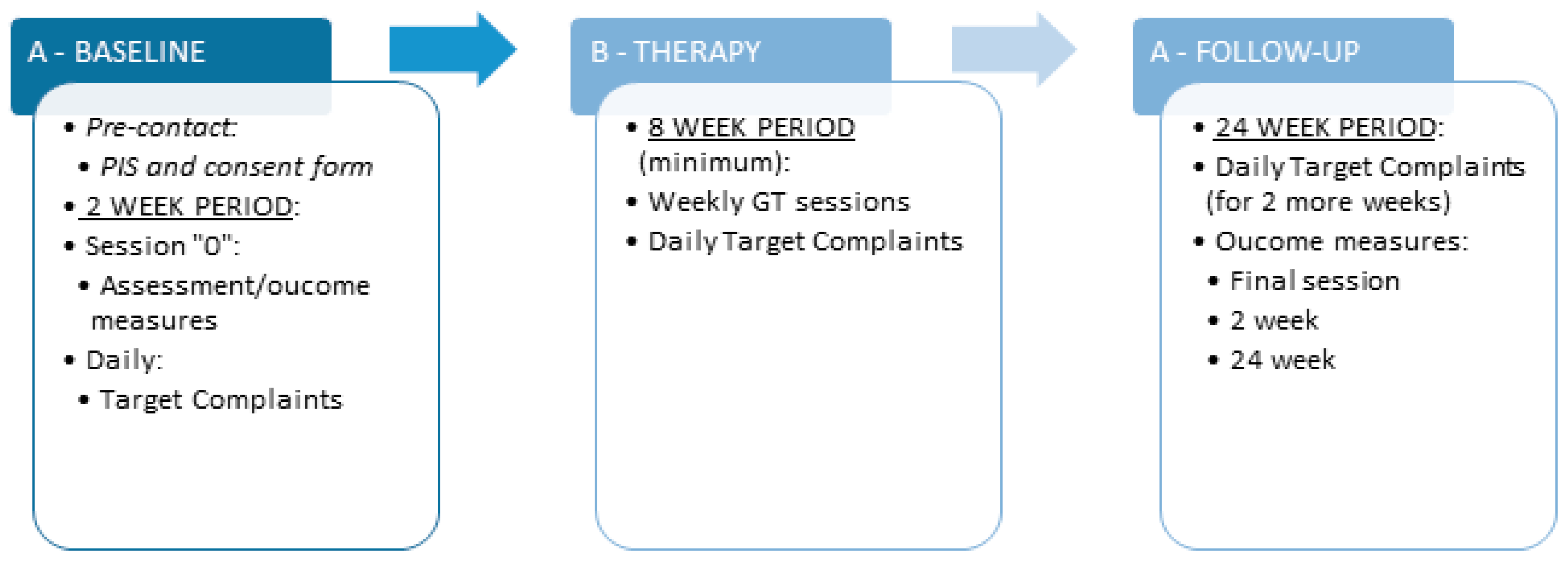

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Study Setting and Intervention

2.3. Sample and Recruitment

2.4. Measures and Data Collection Tools

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Discussion

4. Limitations and Challenges of the Research Protocol

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Global Status Report on the Public Health Response to Dementia; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 2–5. [Google Scholar]

- Hugo, J.; Ganguli, M. Dementia and cognitive impairment: Epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Clin. Geriatr Med. 2014, 30, 421–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöberg, L.; Karlsson, B.; Atti, A.R.; Skoog, I.; Fratiglioni, L.; Wang, H.X. Prevalence of depression: Comparisons of different depression definitions in population-based samples of older adults. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 221, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sexton, C.E.; Mackay, C.E.; Ebmeier, K.P. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Magnetic Resonance Imaging Studies in Late-Life Depression. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2013, 21, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexopoulos, G.S. Depression in the elderly. Lancet 2005, 365, 1961–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butters, M.A.; Young, J.B.; Lopez, O.; Aizenstein, H.J.; Mulsant, B.H.; Reynolds, C.F., 3rd; DeKosky, S.T.; Becker, J.T. Pathways linking late-life depression to persistent cognitive impairment and dementia. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2008, 10, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierksma, A.S.; van den Hove, D.L.; Steinbusch, H.W.; Prickaerts, J. Major depression, cognitive dysfunction and Alzheimer’s disease: Is there a link? Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2010, 626, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolkowitz, O.M.; Epel, E.S.; Reus, V.I.; Mellon, S.H. Depression gets old fast: Do stress and depression accelerate cell aging? Depress Anxiety 2010, 27, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotson, V.M.; Beydoun, M.A.; Zonderman, A.B. Recurrent depressive symptoms and the incidence of dementia and mild cognitive impairment. Neurology 2010, 75, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borza, T.; Engedal, K.; Bergh, S.; Selbæk, G. Older people with depression—A three-year follow-up. Tidsskr. Nor. Laegeforen. 2019, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, D.J.; Han, J.W.; Bae, J.B.; Kim, T.H.; Kwak, K.P.; Kim, B.J.; Kim, S.G.; Kim, J.L.; Moon, S.W.; Park, J.H.; et al. Chronic subsyndromal depression and risk of dementia in older adults. Tidsskr. Nor. Legeforen. 2021, 55, 809–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuring, J.K.; Mathias, J.L.; Ward, L. Prevalence of Depression, Anxiety and PTSD in People with Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2018, 28, 393–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.H.; Lee, S.B.; Lee, T.J.; Lee, D.Y.; Jhoo, J.H.; Youn, J.C.; Choo, I.H.; Choi, E.A.; Jeong, J.W.; Choe, J.Y.; et al. Depression in vascular dementia is quantitatively and qualitatively different from depression in Alzheimer’s disease. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2007, 23, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballard, C.; Neill, D.; O’Brien, J.; McKeith, I.G.; Ince, P.; Perry, R. Anxiety, depression and psychosis in vascular dementia: Prevalence and associations. J. Affect. Disord. 2000, 59, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubenko, G.S.; Zubenko, W.N.; McPherson, S.; Spoor, E.; Marin, D.B.; Farlow, M.R.; Smith, G.E.; Geda, Y.E.; Cummings, J.L.; Petersen, R.C.; et al. A collaborative study of the emergence and clinical features of the major depressive syndrome of Alzheimer’s disease. Am. J. Psychiatry 2003, 160, 857–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition: DSM-5; American Psychiatric Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, A.D.; Goldfarb, D.; Bollam, P.; Khokher, S. Diagnosing and Treating Depression in Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurol. Ther. 2019, 8, 325–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, K.L.; Ritchie, C.S.; Patel, K.; Hunt, L.J.; Covinsky, K.E.; Yaffe, K.; Smith, A.K. Care Settings and Clinical Characteristics of Older Adults with Moderately Severe Dementia. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 1907–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aalten, P.; Jolles, J.; de Vugt, M.E.; Verhey, F.R. The influence of neuropsychological functioning on neuropsychiatric problems in dementia. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2007, 19, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dourado, M.C.; Laks, J. Psychological interventions for neuropsychiatric disturbances in mild and moderate Alzheimer’s disease: Current evidences and future directions. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2016, 13, 1100–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle, C.E.; Dugan, E. Social isolation, loneliness and health among older adults. J. Aging Health 2012, 24, 1346–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, I.E.M.; Martyr, A.; Collins, R.; Brayne, C.; Clare, L. Social isolation and cognitive function in later life: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018, 70, S119–S144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuiper, J.S.; Zuidersma, M.; Oude Voshaar, R.C.; Zuidema, S.U.; van den Heuvel, E.R.; Stolk, R.P.; Smidt, N. Social relationships and risk of dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. Ageing Res. Rev. 2015, 22, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzheimer’s Disease International. Overcoming the Stigma of Dementia. Available online: https://www.alz.co.uk/sites/default/files/pdfs/world-report-2012-summary-sheet.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Werner, P.; Mittleman, M.S.; Goldstein, D.; Heinik, J. Family stigma and caregiver burden in Alzheimer’s disease. Gerontologist 2012, 52, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carers, U.K. Carers Manifesto. Available online: http://www.carersuk.org/for-professionals/policy/policy-library/carers-manifesto (accessed on 15 November 2017).

- Bleijlevens, M.H.; Stolt, M.; Stephan, A.; Zabalegui, A.; Saks, K.; Sutcliffe, C.; Lethin, C.; Soto, M.E.; Zwakhalen, S.M. RightTimePlaceCare Consortium. Changes in caregiver burden and health-related quality of life of informal caregivers of older people with Dementia: Evidence from the European RightTimePlaceCare prospective cohort study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2015, 71, 1378–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilks, S.E.; Croom, B. Perceived stress and resilience in Alzheimer’s disease caregivers: Testing moderation and mediation models of social support. Aging Ment. Health 2008, 12, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mouton, C.P.; Haas, A.; Karmarkar, A.; Kuo, Y.F.; Ottenbacher, K. Elder abuse and mistreatment: Results from medicare claims data. J. Elder Abus. Negl. 2019, 31, 263–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Max, W.; Webber, P.; Fox, P. Alzheimer’s Disease: The Unpaid Burden of Caring. J. Aging Health 1995, 7, 179–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Numbers, K.; Brodaty, H. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with dementia. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2021, 17, 69–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giebel, C.; Hanna, K.; Callaghan, S.; Cannon, J.; Butchard, S.; Shenton, J.; Komuravelli, A.; Limbert, S.; Tetlow, H.; Rogers, C.; et al. Navigating the new normal: Accessing community and institutionalised care for dementia during COVID-19. Aging Ment Health 2021, 28, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canevelli, M.; Valletta, M.; Toccaceli Blasi, M.; Remoli, G.; Sarti, G.; Nuti, F.; Sciancalepore, F.; Ruberti, E.; Cesari, M.; Bruno, G. Facing Dementia During the COVID-19 Outbreak. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020, 68, 1673–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, L.V.D.S.; Calandri, I.L.; Slachevsky, A.; Graviotto, H.G.; Vieira, M.C.S.; Andrade, C.B.; Rossetti, A.P.; Generoso, A.B.; Carmona, K.C.; Pinto, L.A.C.; et al. Impact of Social Isolation on People with Dementia and Their Family Caregivers. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2021, 81, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borelli, W.V.; Augustin, M.C.; de Oliveira, P.B.F.; Reggiani, L.C.; Bandeira-de-Mello, R.G.; Schumacher-Schuh, A.F.; Chaves, M.L.F.; Castilhos, R.M. Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Patients with Dementia Associated with Increased Psychological Distress in Caregivers During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2021, 80, 1705–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Jesús Llibre-Rodríguez, J.; López, A.M.; Valhuerdi, A.; Guerra, M.; Llibre-Guerra, J.J.; Sánchez, Y.Y.; Bosch, R.; Zayas, T.; Moreno, C. Frailty, dependency and mortality predictors in a cohort of Cuban older adults, 2003–2011. MEDICC Rev. 2014, 16, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Action Plan on the Public Health Response to Dementia 2017–2025; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 2–3. [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer Europe. Dementia in Europe Yearbook 2019. In Estimating the Prevalence of Dementia in Europe; Alzheimer Europe: Luxemburg, 2019; pp. 54–55. [Google Scholar]

- GBD 2016 Dementia Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019, 18, 88–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berloto, S.; Notarnicola, E.; Perobelli, E.; Rotolo, A. Italy and the COVID-19 Long-Term Care Situation. Country Report in LTCcovid.org; International Long Term Care Policy Network; CPEC-LSE: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Italian Alzheimer’s Disease Association and CENSIS Foundation (Associazione Italiana Malattia di Alzheimer and Fondanzione CENSIS). L’impatto Economico E Sociale Della Malattia Di Alzheimer: Rifare Il Punto Dopo 16 Anni; Fondazione CENSIS: Rome, Italy, 2016; p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- Barbabella, F.; Poli, A.; Chiatti, C.; Pelliccia, L.; Pesaresi, F. The Compass of NNA: The State of the Art Based on Data. In Care of Non Self-Sufficient Older People in Italy, 6th Report, 2017–2018; NNA Network Non Autosufficienza, Ed.; Maggioli, S.p.A.: Sant’Arcangelo di Romagna, Italy, 2017; pp. 33–54. [Google Scholar]

- Tidoli, R. Domicialirity. Care of Non Self-Sufficient Older People in Italy. 6th Report, 2017–2018; NNA Network Non Autosufficienza, Ed.; Maggioli, S.p.A.: Sant’Arcangelo di Romagna, Italy, 2017; pp. 77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, G. Private Assistants in the Italian Care System: Facts and Policies. Obs. Soc. Br. 2013, 14, 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzheimer’s Disease International and Bupa. La Demencia en América: El Coste y la Prevalencia del Alzheimer y Otros Tipos de Demencia; ADI: London, UK, 2013; pp. 11–12. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez-Robledo, L.M.; Arrieta-Cruz, I. (Eds.) Plan de Acción Alzheimer y Otras Demencias, México 2014, 1st ed.; Instituto Nacional de Geriatría/Secretaría de Salud: Ciudad de México, México, 2014; pp. 49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez-Robledo, L.M.; Arrieta-Cruz, I. Demencias en México: La necesidad de un Plan de Acción [Dementia in Mexico: The need for a National Alzheimer’s Plan]. Gac. Med. Mex. 2015, 151, 667–673. [Google Scholar]

- Netuveli, G.; Blane, D. Quality of life in older ages. Br. Med. Bull. 2008, 85, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, L.C.; Tam, C.W.; Chiu, H.F.; Lui, V.W. Depression and apathy Affect. functioning in community active subjects with questionable dementia and mild Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2007, 22, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starkstein, S.E.; Mizrahi, R. Depression in Alzheimer’s disease. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2006, 6, 887–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tønnesvang, J.; Sommer, U.; Hammink, J.; Sonne, M. Gestalt therapy and cognitive therapy-contrasts or complementarities? Psychotherapy 2010, 47, 586–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnuolo Lobb, M. The Now-for-Next in Psychotherapy: Gestalt Therapy Recounted in Post-Modern Society; Istituto di Gestalt HCC Italy Publ. Co.: Siracusa, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Spagnuolo Lobb, M. The Paradigm of Reciprocity: How to Radically Respect Spontaneity in Clinical Practice. Gestalt Rev. 2019, 23, 232–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffagnino, R. Gestalt Therapy Effectiveness: A Systematic Review of Empirical Evidence. Open J. Soc. Sci. 2019, 7, 66–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, T. Embodiment and personal identity in dementia. Med. Health Care Philos. 2020, 23, 665–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meulmeester, F. Risk of Psychopathology in Old Age. Gestalt Therapy in Clinical Practice: From Psychopathology to the Aesthetic of Contact; Francesetti, G., Gecele, M., Roubal, J., Eds.; Franco Angeli: Milan, Italy, 2013; pp. 281–294. [Google Scholar]

- Spagnuolo Lobb, M.; Wheeler, G. Fundamentals and development of Gestalt Therapy in the contemporary context. Gestalt Rev. 2015, 19, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Spagnuolo Lobb, M.; Garrety, A.; Iacono Isidoro, S. Gestalt Perspective on Depressive Experience: A Questionnaire on Some Phenomenological and Aesthetic Dimensions; (Research Protocol); Istituto di Gestalt HCC Italy: Siracusa, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Drăghici, R. Experiential Psychotherapy in Geriatric Groups. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 33, 979–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azermai, M.; Petrovic, M.; Elseviers, M.M.; Bourgeois, J.; Van Bortel, L.M.; Vander Stichele, R.H. Systematic appraisal of dementia guidelines for the management of behavioural and psychological symptoms. Ageing Res. Rev. 2012, 11, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, A.M.; Radanovic, M.; de Mello, P.C.; Buchain, P.C.; Vizzotto, A.D.; Celestino, D.L.; Stella, F.; Piersol, C.V.; Forlenza, O.V. Nonpharmacological Interventions to Reduce Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia: A Systematic Review. Biomed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 218980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyhe, T.; Reynolds, C.F.; Melcher, T.; Linnemann, C.; Klöppel, S.; Blennow, K.; Zetterberg, H.; Dubois, B.; Lista, S.; Hampel, H. A common challenge in older adults: Classification, overlap, and therapy of depression and dementia. Alzheimer’s. Dement. 2017, 13, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraros, J.; Nwankwo, C.; Patten, S.B.; Mousseau, D.D. The association of antidepressant drug usage with cognitive impairment or dementia, including Alzheimer disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety. 2017, 34, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, C. Antidepressants for depression in patients with dementia: A review of the literature. Consult Pharm. 2014, 29, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orgeta, V.; Qazi, A.; Spector, A.; Orrell, M. Psychological treatments for depression and anxiety in dementia and mild cognitive impairment: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 2015, 207, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheston, R.; Ivanecka, A. Individual and group psychotherapy with people diagnosed with dementia: A systematic review of the literature. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2017, 32, 3–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychological Association. Evidence-based practice in psychology. Am. Psychol. 2006, 61, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krasny-Pacini, A.; Evans, J. Single-case experimental designs to assess intervention effectiveness in rehabilitation: A practical guide. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2018, 61, 164–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the Protection of Natural Persons with Regard to the Processing of Personal Data and on the Free Movement of Such Data, and Repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation). Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/eur/2016/679/contents (accessed on 8 January 2022).

- Herrera, P.; Brownell, P.; Roubal, J.; Mstibovskyi, I.; Glänzer, O. Progetto Gestaltico di Collaborazione Internazionale: Il Caso Singolo, Progetto di Ricerca con Serie Temporali. Manuale per Ricercatori; La Rosa, R., Tosi, S., Eds.; Istituto di Gestalt HCC Italy: Siracusa, Italy, 2020; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, W.J.; Miller, J.P.; Rubin, E.H.; Morris, J.C.; Coben, L.A.; Duchek, J.; Wittels, I.G.; Berg, L. Reliability of the Washington University Clinical Dementia Rating. Arch. Neurol. 1988, 45, 31–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kørner, A.; Lauritzen, L.; Abelskov, K.; Gulmann, N.; Marie Brodersen, A.; Wedervang-Jensen, T.; Marie Kjeldgaard, K. The Geriatric Depression Scale and the Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia. A validity study. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2006, 60, 360–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, J.L.; Mega, M.; Gray, K.; Rosenberg-Thompson, S.; Carusi, D.A.; Gornbein, J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: Comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology 1994, 44, 2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binetti, G.; Mega, M.S.; Magni, E.; Padovani, A.; Rozzini, L.; Bianchetti, A.; Cummings, J.; Trabucchi, M. Behavioral disorders in Alzheimer’s Disease: A transcultural perspective. Arch. Neurol. 1998, 55, 539–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zepeda, M.U.P.; Guerrero, J.A.R.; Carrasco, O.R.; Robledo, L.M.G. P3-038: Validation of the neuropsychiatric inventory questionnaire in a group of Mexican patients with dementia. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2008, 4, T527–T528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufer, D.I.; Cummings, J.L.; Christine, D.; Bray, T.; Castellon, S.; Masterman, D.; MacMillan, A.; Ketchel, P.; DeKosky, S.T. Assessing the impact of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: The Neuropsychiatric Inventory Caregiver Distress Scale. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1998, 46, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, C.P.; Berg, L.; Danziger, W.L.; Coben, L.A.; Martin, R.L. A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. Br. J. Psychiatry 1982, 140, 566–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, J.C. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): Current version and scoring rules. Neurology 1993, 43, 2412–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Bryant, S.E.; Waring, S.C.; Cullum, C.M.; Hall, J.; Lacritz, L.; Massman, P.J.; Lupo, P.J.; Reisch, J.S.; Doody, R. Texas Alzheimer’s Research Consortium Staging Dementia Using Clinical Dementia Rating Scale Sum of Boxes Scores: A Texas Alzheimer’s Research Consortium Study. Arch. Neurol. 2008, 65, 1091–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeo, C.Y.Y.; Chan, M.P.C.; Lim, W.S.; Chong, M.S. P2-100: Clinical Utility of the Clinical Dementia Rating Sum of Boxes in Mild Cognitive Impairment and Dementia in an Asian Population. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2010, 6, S342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battle, C.C.; Imber, S.D.; Hoehn-Saric, R.; Nash, E.R.; Frank, J.D. Target complaints as criteria of improvement. Am. J. Psychother. 1966, 20, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorer, C. Improvement with and without psychotherapy. Dis. Nerv. Syst. 1970, 31, 155–160. [Google Scholar]

- Frey, J.; Heckel, R.V.; Salzberg, H.C.; Wackwitz, J. Demographic variables as predictors of outcome in psychotherapy with children. J. Clin. Psychol. 1976, 32, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, D.W. UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): Reliability, validity, and factor structure. J. Pers. Assess. 1996, 66, 20–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boffo, M.; Mannarini, S.; Munari, C. Exploratory Structure Equation Modeling of the UCLA Loneliness Scale: A contribution to the Italian adaptation. TPM 2012, 19, 345–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancho, P.; Pinazo-Hernandis, S.; Donio-Bellegarde, M.; Tomás, J.M. Validation of the University of California, Los Angeles Loneliness Scale (version 3) in Spanish older population: An application of exploratory structural equation modelling. Aust. Psychol. 2020, 55, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logsdon, R.G.; Gibbons, L.E.; McCurry, S.M.; Teri, L. Quality of life in Alzheimer’s disease: Patient and caregiver reports. J. Ment. Health Aging 1999, 5, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Zarit, S.H.; Reever, K.E.; Back-Peterson, J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: Correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontologist 1980, 20, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hérbert, R.; Bravo, G.; Préville, M. Reliability, validity, and reference values of the Zarit Burden Interview for assessing informal caregivers of community-dwelling older persons with dementia. Can. J. Aging 2000, 19, 494–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI). Available online: https://eprovide.mapi-trust.org/instruments/zarit-burden-interview (accessed on 23 November 2021).

- Archbold, P.G.; Stewart, B.J.; Greenlick, M.R.; Harvath, T. Mutuality and preparedness as predictors of caregiver role strain. Res. Nurs. Health 1990, 13, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godwin, K.M.; Swank, P.R.; Vaeth, P.; Ostwald, S.K. The longitudinal and dyadic effects of mutuality on perceived stress for stroke survivors and their spousal caregivers. Aging Ment. Health 2013, 17, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, K.S.; Stewart, B.J.; Archbold, P.G.; Carter, J.H. Optimism, pessimism, mutuality, and gender: Predicting 10-year role strain in Parkinson’s disease spouses. Gerontologist 2009, 49, 378–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halm, M.A.; Treat-Jacobson, D.; Lindquist, R.; Savik, K. Caregiver burden and outcomes of caregiving of spouses of patients who undergo coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Heart Lung 2007, 36, 170–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froyd, J.E.; Lambert, M.J.; Froyd, J.D. A review of practices of psychotherapy outcome measurement. J. Ment. Health 1996, 5, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, C.; Connell, J.; Barkham, M.; Margison, F.; McGrath, G.; Mellor-Clark, J.; Audin, K. Towards a standardised brief outcome measure: Psychometric properties and utility of the CORE–OM. Br. J. Psychiatry 2002, 180, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkham, M.; Culverwell, A.; Spindler, K.; Twigg, E. The CORE-OM in an older adult population: Psychometric status, acceptability, and feasibility. Aging Ment. Health 2005, 9, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogarty, M.; Bhar, S.; Theiler, S. Development and validation of the Gestalt Therapy Fidelity Scale. Psychother. Res. 2020, 30, 495–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borckardt, J.J.; Nash, M.R.; Murphy, M.D.; Moore, M.; Shaw, D.; O’Neil, P. Clinical practice as natural laboratory for psychotherapy research: A guide to case-based time-series analysis. Am. Psychol. 2008, 63, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, J.M. Efficacy of behavioral interventions for reducing problem behavior in persons with autism: A quantitative synthesis of single-subject research. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2003, 24, 120–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olive, M.L.; Smith, B.W. Effect size calculations and single subject designs. Educ. Psychol. 2005, 25, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delfs, C.H.; Campbell, J.M. A quantitative synthesis of developmental disability research: The impact of functional assessment methodology on treatment effectiveness. Behav. Anal. Today 2010, 11, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitwood, T. The experience of dementia. Aging Ment. Health 1997, 1, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewing, J. Personhood and dementia: Revisiting Tom Kitwood’s ideas. Int. J. Older People Nurs. 2008, 3, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, P.; Mstibovskyi, I.; Roubal, J.; Brownell, P. The Single-Case, Time-Series Study. Int. J. Psychother. 2020, 24, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminzadeh, F.; Byszewski, A.; Molnar, F.J.; Eisner, M. Emotional impact of dementia diagnosis: Exploring persons with dementia and caregivers’ perspectives. Aging Ment. Health 2007, 11, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bopp-Kistler, I. Diagnoseeröffnung und Begleitung [Disclosing the diagnosis and guidance]. Ther. Umsch. 2015, 72, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Instrument | Variable | Point of View | When It Is Used |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neuropsychiatric inventory (NPI) | Neuropsychiatric symptoms (patient) and caregiver distress | Expert judge interviews caregiver | Session “0” |

| Clinical dementia rating (CDR) | Cognitive symptoms and dementia diagnosis | Expert judge interviews patient | Session “0” and follow-up |

| Geriatric depression scale (GDS) | Depressive symptoms | Patient self-report | Session “0”, final session and follow up |

| Anxiety indicated by an NPI-A score of 4 or more | Anxiety symptoms | Expert judge interviews Caregiver | Session “0”, final session and follow up |

| Target complaints (TC) | Specific results of therapy | Patient self-report (after co-construction of instrument with a therapist) | Co-constructed at session “0” Client completes questionnaire every day after that until follow up session |

| UCLA-LS3 | Loneliness | Patient self-report | Session “0”, final session and follow up |

| QOL-AD | Quality of life | Expert judge interviews patient and family caregiver self-report | Session “0”, final session and follow up |

| Ad-hoc common assessment tool | Level of care | Family member self-report | Session “0” |

| Zarit burden inventory | Caregiver level of stress | Family member self-report | Session “0”, final session and follow up |

| The mutuality scale | Mutuality of relationship | Patient and caregiver self-report | Session “0”, final session and follow up |

| CORE–OM | Overall results of therapy | Patient self-report | Session “0”, final session and follow up |

| Gestalt therapy fidelity scale (GTFS) | Treatment fidelity | Expert judge observes therapy sessions | End of first therapy treatment |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Merizzi, A.; Biasi, R.; Zamudio, J.F.Á.; Spagnuolo Lobb, M.; Di Rosa, M.; Santini, S. A Single-Case Design Investigation for Measuring the Efficacy of Gestalt Therapy to Treat Depression in Older Adults with Dementia in Italy and in Mexico: A Research Protocol. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3260. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063260

Merizzi A, Biasi R, Zamudio JFÁ, Spagnuolo Lobb M, Di Rosa M, Santini S. A Single-Case Design Investigation for Measuring the Efficacy of Gestalt Therapy to Treat Depression in Older Adults with Dementia in Italy and in Mexico: A Research Protocol. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(6):3260. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063260

Chicago/Turabian StyleMerizzi, Alessandra, Rosanna Biasi, José Fernando Álvarez Zamudio, Margherita Spagnuolo Lobb, Mirko Di Rosa, and Sara Santini. 2022. "A Single-Case Design Investigation for Measuring the Efficacy of Gestalt Therapy to Treat Depression in Older Adults with Dementia in Italy and in Mexico: A Research Protocol" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 6: 3260. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063260

APA StyleMerizzi, A., Biasi, R., Zamudio, J. F. Á., Spagnuolo Lobb, M., Di Rosa, M., & Santini, S. (2022). A Single-Case Design Investigation for Measuring the Efficacy of Gestalt Therapy to Treat Depression in Older Adults with Dementia in Italy and in Mexico: A Research Protocol. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(6), 3260. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063260