Palliative Care in Older People with Multimorbidities: A Scoping Review on the Palliative Care Needs of Patients, Carers, and Health Professionals

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identifying Relevant Studies

- What are the PC needs for older patients with multimorbidities?

- What are the PC needs for caregivers of older patients with multimorbidities?

- What are the needs influencing PC provision by health professionals for older patients with multimorbidities and their caregivers?

- (((((palliative care [Title/Abstract]) AND patients [Title/Abstract]) AND needs [Title/Abstract]) OR preferences [Title/Abstract]) AND older [Title/Abstract] OR elderly [Title/Abstract]).

- ((palliative care [Title/Abstract]) OR palliative care unit AND health professionals[Title/Abstract] AND perceptions [Title/Abstract]) OR needs [Title/Abstract]) NOT patients [Title/Abstract]).

- ((palliative care [Title/Abstract]) AND families [Title/Abstract] OR caregiver [Title/Abstract]) AND needs [Title/Abstract]) OR perceptions [Title/Abstract]) AND elderly [Title/Abstract]) OR aged [Title/Abstract]).

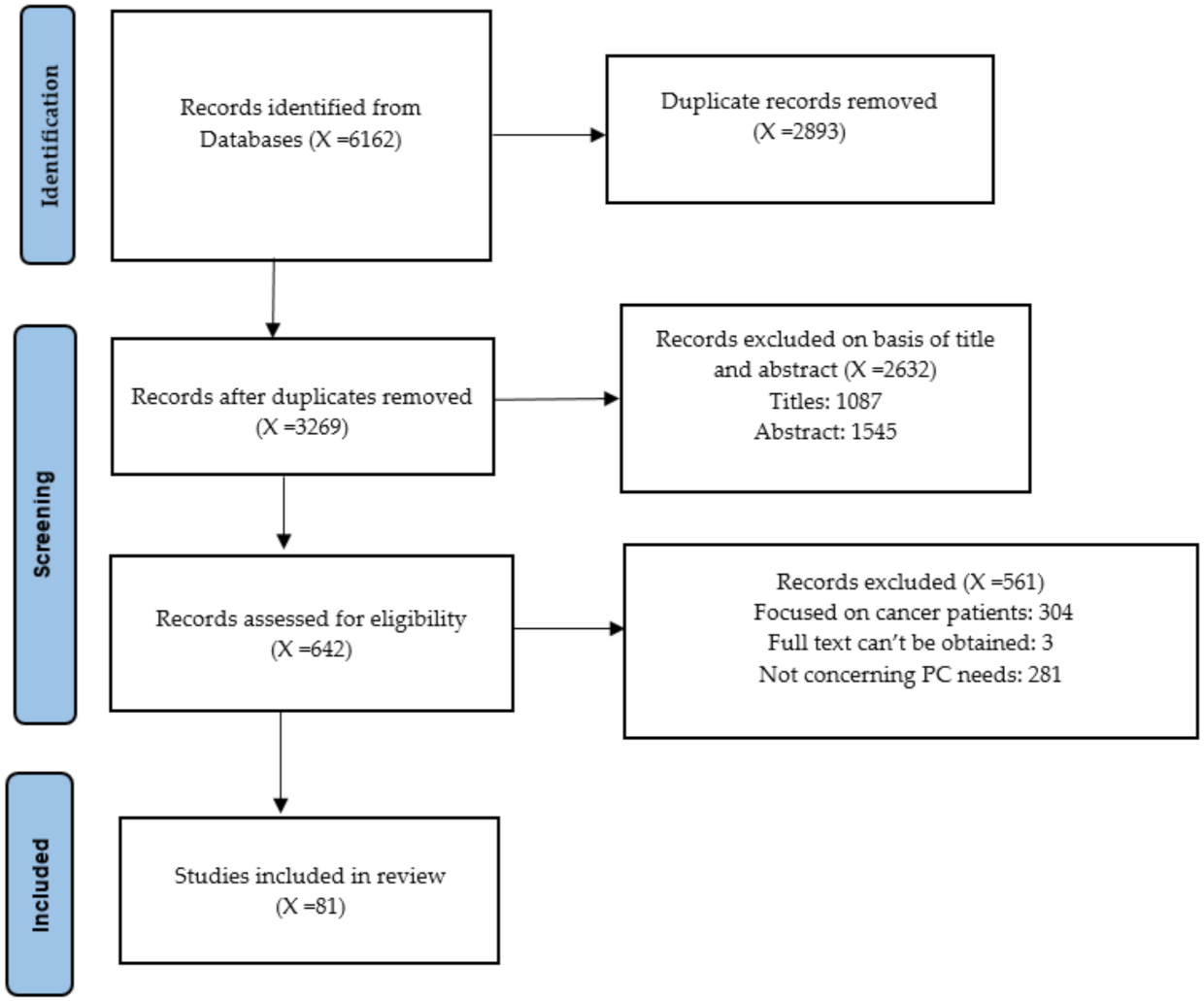

2.2. Study Selection

2.3. Charting the Data

2.4. Collating, Summarizing and Reporting the Results

3. Results

3.1. Patients’ Needs

3.1.1. Emotional/Mental Needs

3.1.2. Physical Needs

3.1.3. Information Needs

3.1.4. Spiritual Needs

3.1.5. Other Needs

3.2. Caregivers’ Needs

3.2.1. Emotional/Mental Needs

3.2.2. Physical Needs

3.2.3. Financial Needs

3.2.4. Social Needs

3.2.5. Other Needs

3.3. Professionals’ Needs

3.3.1. Needs in PC Provision

3.3.2. Training Needs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. WHO Definition of Palliative Care. 2007. Available online: http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/ (accessed on 22 December 2020).

- Wong, M.; Ho, L.; Hui, E.; Miaskowski, Y. Burden of living with multiple concurrent symptoms in patients with end-stage renal disease. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 2589–2601. [Google Scholar]

- Connor, S.R.; Bermedo, M.S. Global Atlas of Palliative Care at the End of Life. January 2014. Available online: http://www.thewhpca.org/resources/global-atlas-on-end-of-life-care (accessed on 30 December 2021).

- Downar, J.; Chou, Y.C.; Ouellet, D.; La Delfa, I.; Blacker, S.; Bennett, M.; Petch, C.; Cheng, S.M. Survival duration among patients with a noncancer diagnosis admitted to a palliative care unit: A retrospective study. J. Palliat. Med. 2012, 15, 661–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haun, M.W.; Estel, S.; Rücker, G.; Friederich, H.; Villalobos, M.; Thomas, M.; Hartmann, M. Early palliative care for adults with advanced cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, CD011129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hui, D.; Kim, Y.J.; Park, J.C.; Zhang, Y.; Strasser, F.; Cherny, N.; Kaasa, S.; Davis, M.P.; Bruera, E. Integration of oncology and palliative care: A systematic review. Oncologist 2015, 20, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandieri, E.; Sichetti, D.; Romero, M.; Fanizza, C.; Belfiglio, M.; Buonaccorso, L.; Artioli, F.; Campione, F.; Tognoni, G.; Luppi, M. Impact of early access to a palliative/supportive care intervention on pain management in patients with cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2012, 23, 2016–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Molassiotis, A.; Chung, B.P.M.; Tan, J.Y. Unmet care needs of advanced cancer patients and their informal caregivers: A systematic review. BMC Palliat. Care 2018, 17, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Noncommunicable Diseases; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed on 22 December 2020).

- Johnston, M.; Crilly, M.; Black, C.; Prescott, G.J.; Mercer, S. Defining and measuring multimorbidity: A systematic review of systematic reviews. Eur. J. Public Health 2019, 29, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, M.J.; Wu, F.; Guo, Y.; Robledo, L.M.G.; O’Donnell, M.; Sullivan, R.; Yusuf, S. The burden of disease in older people and implications for health policy and practice. Lancet 2015, 385, 549–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingston, A.; Robinson, L.; Booth, H.; Knapp, M.; Jagger, C. MODEM Project. Projections of multi-morbidity in the older population in England to 2035: Estimates from the Population Ageing and Care Simulation (PACSim) model. Age Ageing 2018, 47, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, C. End of Life Care Strategy: Quality Markers and Measures for End of Life Care; Department of Health: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMAScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, M.R.; Kinloch, K.; Groves, K.E.; Jack, B.A. Meeting patients’ spiritual needs during end-of-life care: A qualitative study of nurses’ and healthcare professionals’ perceptions of spiritual care training. J. Clin. Nurs. 2019, 28, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, S.Q.; Dein, S. The difficulties assessing spiritual distress in palliative care patients: A qualitative study. Ment. Health Relig. Cult. 2011, 14, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajwah, S.; Higginson, I.J.; Ross, J.R.; Wells, A.U.; Birring, S.S.; Riley, J.; Koffman, J. The palliative care needs for fibrotic interstitial lung disease: A qualitative study of patients, informal caregivers and health professionals. Palliat. Med. 2013, 27, 869–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, R.W.; Lowton, K.; Robert, G.; Grudzen, C.; Grocott, P. Using Experience-based Co-design with older patients, their families and staff to improve palliative care experiences in the Emergency Department: A reflective critique on the process and outcomes. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2017, 68, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bone, A.E.; Morgan, M.; Maddocks, M.; Sleeman, K.E.; Wright, J.; Taherzadeh, S.; Ellis-Smith, C.; Higginson, I.J.; Evans, C.J. Developing a model of short-term integrated palliative and supportive care for frail older people in community settings: Perspectives of older people, carers and other key stakeholders. Age Ageing 2016, 45, 863–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckingham, S.; Kendall, M.; Ferguson, S.; MacNee, W.; Sheikh, A.; White, P.; Worth, A.; Boyd, K.; Murray, S.A.; Pinnock, H. HELPing older people with very severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (HELP-COPD): Mixed-method feasibility pilot randomised controlled trial of a novel intervention. Npj Prim. Care Respir. Med. 2015, 25, 15020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, N.; Maio, L.; Vedavanam, K.; Manthorpe, J.; Vernooij-Dassen, M.; Iliffe, S.; IMPACT Research Team. Barriers to the provision of high-quality palliative care for people with dementia in England: A qualitative study of professionals’ experiences. Health Soc. Care Community 2014, 22, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, J.; Farquhar, M.; Brayne, C.; Barclay, S.; Cambridge City over-75s Cohort (CC75C) Study Collaboration. Death and the oldest old: Attitudes and preferences for end-of-life care-qualitative research within a population-based cohort study. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0150686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, C.; Cobb, M.; Gott, M.; Ingleton, C. Barriers to providing palliative care for older people in acute hospitals. Age Ageing 2011, 40, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gott, M.; Ingleton, C.; Bennett, M.I.; Gardiner, C. Transitions to palliative care in acute hospitals in England: Qualitative study. BMJ 2011, 342, d1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handley, M.; Goodman, C.; Froggatt, K.; Mathie, E.; Gage, H.; Manthorpe, J.; Barclay, S.; Crang, C.; Iliffe, S. Living and dying: Responsibility for end-of-life care in care homes without on-site nursing provision—A prospective study. Health Soc. Care Community 2014, 22, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livingston, G.; Pitfield, C.; Morris, J.; Manela, M.; Lewis-Holmes, E.; Jacobs, H. Care at the end of life for people with dementia living in a care home: A qualitative study of staff experience and attitudes. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2012, 27, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, A.; Kendall, M.; Starr, J.M.; Murray, S.A. Physical, social, psychological and existential trajectories of loss and adaptation towards the end of life for older people living with frailty: A serial interview study. BMC Geriatr. 2016, 16, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, B.; Epiphaniou, E.; Nanton, V.; Donaldson, A.; Shipman, C.; Daveson, B.A.; Harding, R.; Higginson, I.; Munday, D.; Barclay, S.; et al. Coordination of care for individuals with advanced progressive conditions: A multi-site ethnographic and serial interview study. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2013, 63, e580–e588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayland, C.R.; Mulholland, H.; Gambles, M.; Ellershaw, J.; Stewart, K. How well do we currently care for our dying patients in acute hospitals: The views of the bereaved relatives? BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2017, 7, 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaughlin, D.; Barr, O.; McIlfatrick, S.; McConkey, R. Developing a best practice model for partnership practice between specialist palliative care and intellectual disability services: A mixed methods study. Palliat. Med. 2014, 28, 1213–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.P.; Bamford, C.; Exley, C.; Robinson, L. Expert views on the factors enabling good end of life care for people with dementia: A qualitative study. BMC Palliat. Care 2015, 14, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, M.; Bamford, C.; McLellan, E.; Lee, R.P.; Exley, C.; Hughes, J.C.; Harrison-Dening, K.; Robinson, L. End-of-life care: A qualitative study comparing the views of people with dementia and family carers. Palliat. Med. 2018, 32, 631–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, T.; Ingleton, C.; Gardiner, C.; Parker, C.; Gott, M.; Noble, B. Symptom burden, palliative care need and predictors of physical and psychological discomfort in two UK hospitals. BMC Palliat. Care 2013, 12, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldron, M.; Kernohan, W.G.; Hasson, F.; Foster, S.; Cochrane, B. What Do Social Workers Think about the Palliative Care Needs of People with Parkinson’s Disease? Br. J. Soc. Work 2013, 43, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boersma, I.; Jones, J.; Coughlan, C.; Carter, J.; Bekelman, D.; Miyasaki, J.; Kutner, J.; Kluger, B. Palliative care and Parkinson’s disease: Caregiver perspectives. J. Palliat. Med. 2017, 20, 930–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, E.; Daly, J.; Johnson, A.; Harrison, K.; Easterbrook, S.; Bidewell, J.; Stewart, H.; Noel, M.; Hancock, K. Challenges for professional care of advanced dementia. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2009, 15, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cimino, N.M.; Lockman, K.; Grant, M.; McPherson, M.L. Knowledge, Skills, and Attitudes in Caring for Older Adults with Advanced Illness among Staff Members of Long-Term Care and Assisted Living Facilities: An Educational Needs Assessment. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2016, 33, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grudzen, C.R.; Richardson, L.D.; Morrison, M.; Cho, E.; Morrison, R.S. Palliative care needs of seriously ill, older adults presenting to the emergency department. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2010, 17, 1253–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, S.; Kolliakou, A.; Petkova, H.; Froggatt, K.; Higginson, I.J. Interventions for improving palliative care for older people living in nursing care homes. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011, 3, CD007132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallman, K.; Greenwald, R.; Reidenouer, A.; Pantel, L. Living with advanced illness: Longitudinal study of patient, family, and caregiver needs. Perm. J. 2012, 16, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, J.; Ko, E.; Kramer, B.J. Facilitating advance care planning with ethnically diverse groups of frail, low-income elders in the USA: Perspectives of care managers on challenges and recommendations. Health Soc. Care Community 2014, 22, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, G.K.; Haime, V.; Jackson, V.; Chittenden, E.; Mehta, D.H.; Park, E.R. Promoting resiliency among palliative care clinicians: Stressors, coping strategies, and training needs. J. Palliat. Med. 2015, 18, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thai, J.N.; Barnhart, C.E.; Cagle, J.; Smith, A.K. “It Just Consumes Your Life”: Quality of Life for Informal Caregivers of Diverse Older Adults With Late-Life Disability. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2016, 33, 644–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloomer, M.J.; Botti, M.; Runacres, F.; Poon, P.; Barnfield, J.; Hutchinson, A.M. Cultural considerations at end of life in a geriatric inpatient rehabilitation setting. Collegian 2019, 26, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broom, A.; Kirby, E.; Good, P.; Wootton, J.; Adams, J. Specialists’ experiences and perspectives on the timing of referral to palliative care: A qualitative study. J. Palliat. Med. 2012, 15, 1248–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, E.; Bidewell, J.; Hancock, K.; Johnson, A.; Easterbrook, S. Community palliative care nurse experiences and perceptions of follow-up bereavement support visits to carers. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2012, 18, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleming, R.; Kelly, F.; Stillfried, G. ‘I want to feel at home’: Establishing what aspects of environmental design are important to people with dementia nearing the end of life. BMC Palliat. Care 2015, 14, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, E.T.; Harrison, R.; Hanly, L.; Psirides, A.; Zammit, A.; McFarland, K.; Dawson, A.; Hillman, K.; Barr, M.; Cardona, M. End-of-life priorities of older adults with terminal illness and caregivers: A qualitative consultation. Health Expect. 2019, 22, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sealey, M.; O’Connor, M.; Aoun, S.M.; Breen, L.J. Exploring barriers to assessment of bereavement risk in palliative care: Perspectives of key stakeholders. BMC Palliat. Care 2015, 14, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneesby, L.; Satchell, R.; Good, P.; van der Riet, P. Death and dying in Australia: Perceptions of a Sudanese community. J. Adv. Nurs. 2011, 67, 2696–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.M.; O’Connor, M.M.; Miles, G.; Klein, B.; Schattner, P. GP and nurses’ perceptions of how after hours care for people receiving palliative care at home could be improved: A mixed methods study. BMC Palliat. Care 2009, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wiese, M.; Stancliffe, R.J.; Balandin, S.; Howarth, G.; Dew, A. End-of-life care and dying: Issues raised by staff supporting older people with intellectual disability in community living services. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2012, 25, 571–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J.J.; Dodek, P.; Lamontagne, F.; Downar, J.; Sinuff, T.; Jiang, X.; Day, A.G.; Heyland, D.K. What really matters in end-of-life discussions? Perspectives of patients in hospital with serious illness and their families. CMAJ 2014, 186, E679–E687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, J.; Porterfield, P.; Bouchal, S.R.; Heyland, D. ‘Not yet’and ‘Just ask’: Barriers and facilitators to advance care planning—A qualitative descriptive study of the perspectives of seriously ill, older patients and their families. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2015, 5, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher, R.; Krawczyk, M. Family members’ perceptions of end-of-life care across diverse locations of care. BMC Palliat. Care 2013, 12, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacLeod, A.; Skinner, M.W.; Low, E. Supporting hospice volunteers and caregivers through community-based participatory research. Health Soc. Care Community 2012, 20, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddalena, V.; O’Shea, F.; Barrett, B. An Exploration of Palliative Care Needs of People with End-Stage Renal Disease on Dialysis: Family Caregiver’s Perspectives. J. Palliat. Care 2018, 33, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mistry, B.; Bainbridge, D.; Bryant, D.; Toyofuku, S.T.; Seow, H. What matters most for end-of-life care? Perspectives from community-based palliative care providers and administrators. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e007492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarti, A.J.; Bourbonnais, F.F.; Landriault, A.; Sutherland, S.; Cardinal, P. An Interhospital, Interdisciplinary Needs Assessment of Palliative Care in a Community Critical Care Context. J. Palliat. Care 2015, 31, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brueckner, T.; Schumacher, M.; Schneider, N. Palliative care for older people—Exploring the views of doctors and nurses from different fields in Germany. BMC Palliat. Care 2009, 8, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, K.; Schneider, N.; Bleidorn, J.; Klindtworth, K.; Jünger, S.; Müller-Mundt, G. Caring for frail older people in the last phase of life—The general practitioners’ view. BMC Palliat. Care 2016, 15, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klindtworth, K.; Oster, P.; Hager, K.; Krause, O.; Bleidorn, J.; Schneider, N. Living with and dying from advanced heart failure: Understanding the needs of older patients at the end of life. BMC Geriatr. 2015, 15, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krug, K.; Ballhausen, R.A.; Bölter, R.; Engeser, P.; Wensing, M.; Szecsenyi, J.; Peters-Klimm, F. Challenges in supporting lay carers of patients at the end of life: Results from focus group discussions with primary healthcare providers. BMC Fam. Pract. 2018, 19, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M.; Claus, M.; Zepf, K.I.; Fischbeck, S.; Pinzon, L.C.E. Dying in Germany—Unfulfilled needs of relatives in different care settings. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2012, 44, 542–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziehm, J.; Farin, E.; Schäfer, J.; Woitha, K.; Becker, G.; Köberich, S. Palliative care for patients with heart failure: Facilitators and barriers—A cross sectional survey of German health care professionals. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Den Herder-van der Eerden, M.; van Wijngaarden, J.; Payne, S.; Preston, N.; Linge-Dahl, L.; Radbruch, L.; Van Beek, K.; Menten, J.; Busa, C.; Csikos, A.; et al. Integrated palliative care is about professional networking rather than standardisation of care: A qualitative study with healthcare professionals in 19 integrated palliative care initiatives in five European countries. Palliat. Med. 2018, 32, 1091–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, C.; Evans, C.; Wilcock, J.; Froggatt, K.; Drennan, V.; Sampson, E.; Iliffe, S. End of life care for community dwelling older people with dementia: An integrated review. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2010, 25, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higginson, I.J.; Daveson, B.A.; Morrison, R.; Deokhee, Y.; Meier, D.; Smith, M.; Ryan, K.; McQuillan, R.; Johnston, B.; Normand, C. Social and clinical determinants of preferences and their achievement at the end of life: Prospective cohort study of older adults receiving palliative care in three countries. BMC Geriatr. 2017, 17, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, L.-S.; Huang, X.; Hu, W.-Y.; O’Connor, M.; Lee, S. Experiences and perspectives of older people regarding advance care planning: A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Palliat. Med. 2017, 31, 394–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, J.; Pattenden, J.; Candy, B.; Beattie, J.; Jones, L. Palliative care in advanced heart failure: An international review of the perspectives of recipients and health professionals on care provision. J. Card. Fail. 2011, 17, 231–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selman, L.; Brighton, L.; Sinclair, S.; Karvinen, I.; Egan, R.; Speck, P.; Powell, R.; Deskur-Smielecka, E.; Glajchen, M.; Adler, S.; et al. Patients’ and caregivers’ needs, experiences, preferences and research priorities in spiritual care: A focus group study across nine countries. Palliat. Med. 2018, 32, 216–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smallwood, N.; Currow, D.; Booth, S.; Spathis, A.; Irving, L.; Philip, J. Attitudes to specialist palliative care and advance care planning in people with COPD: A multi-national survey of palliative and respiratory medicine specialists. BMC Palliat. Care 2018, 17, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virdun, C.; Luckett, T.; Davidson, P.; Phillips, J. Dying in the hospital setting: A systematic review of quantitative studies identifying the elements of end-of-life care that patients and their families rank as being most important. Palliat. Med. 2015, 29, 774–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheerens, C.; Deliens, L.; Van Belle, S.; Joos, G.; Pype, P.; Chambaere, K. “A palliative end-stage COPD patient does not exist”: A qualitative study of barriers to and facilitators for early integration of palliative home care for end-stage COPD. NPJ Prim. Care Resp. Med. 2018, 28, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siouta, N.; Clement, P.; Aertgeerts, B.; Van Beek, K.; Menten, J. Professionals’ perceptions and current practices of integrated palliative care in chronic heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A qualitative study in Belgium. BMC Palliat. Care 2018, 17, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udo, C.; Neljesjö, M.; Strömkvist, I.; Elf, M. A qualitative study of assistant nurses’ experiences of palliative care in residential care. Nurs. Open 2018, 5, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallerstedt, B.; Benzein, E.; Schildmeijer, K.; Sandgren, A. What is palliative care? Perceptions of healthcare professionals. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2019, 33, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennbrant, S.; Hjorton, C.; Nilsson, C.; Karlsson, M. “The challenge of joining all the pieces together”—Nurses’ experience of palliative care for older people with advanced dementia living in residential aged care units. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 3835–3846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, G.A.F.D.L.; Menezes, R.M.P.D.; Enders, B.C.; Teixeira, G.A.; Dantas, D.N.A.; Oliveira, D.R.C.D. Meanings attributed to palliative care by health professional in the primary care context1. Texto Contexto Enferm. 2018, 27, e5740016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fan, S.; Lin, I.; Hsieh, J.; Chang, C. Psychosocial care provided by physicians and nurses in palliative care: A mixed methods study. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2017, 53, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenherr, G.; Meyer-Zehnder, B.; Kressig, R.; Reiter-Theil, S. To speak, or not to speak-do clinicians speak about dying and death with geriatric patients at the end of life? Swiss Med. Wkly. 2012, 142, w13563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolt, E.; Pasman, H.; Willems, D.; Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B. Appropriate and inappropriate care in the last phase of life: An explorative study among patients and relatives. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijnsdorp, F.M.; Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B.D.; Boot, C.R. Combining paid work and family care for a patient at the end of life at home: Insights from a qualitative study among caregivers in the Netherlands. BMC Palliat. Care 2021, 2021 93, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midtbust, H.; Alnes, R.; Gjengedal, E.; Lykkeslet, E. Perceived barriers and facilitators in providing palliative care for people with severe dementia: The healthcare professionals’ experiences. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fryer, S.; Bellamy, G.; Morgan, T.; Gott, M. “Sometimes I’ve gone home feeling that my voice hasn’t been heard”: A focus group study exploring the views and experiences of health care assistants when caring for dying residents. BMC Palliat. Care 2016, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mousing, C.; Timm, H.; Lomborg, K.; Kirkevold, M. Barriers to palliative care in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in home care: A qualitative study of the perspective of professional caregivers. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 27, 650–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, H.Y.L.; Chan, C.N.C.; Man, C.W.; Chiu, A.D.W.; Liu, F.C.; Leung, E.M.F. Key Components for the Delivery of Palliative and End-of-Life Care in Care Homes in Hong Kong: A Modified Delphi Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, S.; Momen, N.; Case-Upton, S.; Kuhn, I.; Smith, E. End-of-life care conversations with heart failure patients: A systematic literature review and narrative synthesis. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2011, 61, e49–e62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Witt Jansen, B.; Brazil, K.; Passmore, P.; Buchanan, H.; Maxwell, D.; McIlfatrick, S.J.; Morgan, S.M.; Watson, M.; Parsons, C. ‘There’s a Catch-22’—The complexities of pain management for people with advanced dementia nearing the end of life: A qualitative exploration of physicians’ perspectives. Palliat. Med. 2017, 31, 734–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennings, J.; Froggatt, K.; Keady, J. Approaching the end of life and dying with dementia in care homes: The accounts of family carers. Rev. Clin. Gerontol. 2010, 20, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aebischer, S.; Nikolic, R.; Lazic, R.; Dropic, T.; Vogel, B.; Lab, S.; Lachat, P.; Hudelson, C.; Matis, S. Addressing the needs of terminally-ill patients in Bosnia-Herzegovina: Patients’ perceptions and expectations. BMC Palliat. Care 2018, 17, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, M.; Warner, A.; Davies, N.; Iliffe, S.; Manthorpe, J.; Ahmedzhai, S. Palliative care services for people with dementia: A synthesis of the literature reporting the views and experiences of professionals and family carers. Dementia 2014, 13, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, S.; Mason, H.; Poole, M.; Vale, L.; Robinson, L. What is important at the end of life for people with dementia? The views of people with dementia and their carers. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2016, 32, 1037–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motamedi, M.; Brandenburg, C.; Bakhit, M. Concerns and potential improvements in end-of-life care from the perspectives of older patients and informal caregivers: A scoping review. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steindal, S.A.; Nes, A.A.G.; Godskesen, T.E.; Dihle, A.; Lind, S.; Winger, A.; Klarare, A. Patients’ experiences of telehealth in palliative home care: Scoping review. J. Med. Intern. Res. 2020, 22, 16218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathews, J.; Hannon, B.; Zimmermann, C. Models of Integration of Specialized Palliative Care with Oncology. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2021, 22, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gijsberts, M.; Liefbroer, A.; Otten, R.; Olsman, E. Spiritual Care in Palliative Care: A Systematic Review of the Recent European Literature. Med. Sci. 2019, 7, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criterion | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Period | 1 January 2009 until 7 February 2022 | Published before 2009 |

| Language | English | Any other languages |

| Type of studies | Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method studies published in peer-reviewed journals | Letters, comments, conference abstracts, editorials, doctoral thesis |

| Type of participants | Older patients with multimorbidity (presence of two or more long-term health conditions) Caregivers of older patients with multimorbidity Health professionals in any PC healthcare setting | Cancer patients Patients who do not have multimorbidity (presence of two or more long-term health conditions) Patients under 60 years of age |

| Type of outcomes | Concerning Palliative care needs | Not concerning palliative care needs |

| Patients | Caregivers | Professionals |

|---|---|---|

| Emotional/mental needs Physical needs Information needs Spiritual needs Other needs | Emotional/mental needs Physical needs Social needs Financial needs Other needs | PC provision Training needs |

| Sources of Data | References |

|---|---|

| Individual Interviews | [18,26,27,32,44,46,48,58,59,62,63,76,77,80,82,90,92] |

| Focus groups | [17,18,25,48,50,51,57,61,64,72,75,78,86] |

| Individual interview and focus group or similar | [22,24,28,33,35,36,42,47,49,53,85,87] |

| Individual interview and questionnaire or survey | [65,81] |

| Survey or questionnaire | [30,34,37,38,39,52,56,66,69,73,83] |

| Reviews | [34,62,64,65,68,80,82,84] |

| Individual interview, focus group or similar and survey | [20,31,54,60] |

| Individual interview focus group or similar and survey and RTC | [21] |

| Individual interview, ethnographic observation | [29,41] |

| Non-participant observation, semi-structured interviews, focus groups and a co-design event | [19] |

| Individual interview, retrospective audit of existing hospital databases | [45] |

| Q-methodology (combination of qualitative and quantitative techniques) | [94] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Llop-Medina, L.; Fu, Y.; Garcés-Ferrer, J.; Doñate-Martínez, A. Palliative Care in Older People with Multimorbidities: A Scoping Review on the Palliative Care Needs of Patients, Carers, and Health Professionals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3195. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063195

Llop-Medina L, Fu Y, Garcés-Ferrer J, Doñate-Martínez A. Palliative Care in Older People with Multimorbidities: A Scoping Review on the Palliative Care Needs of Patients, Carers, and Health Professionals. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(6):3195. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063195

Chicago/Turabian StyleLlop-Medina, Laura, Yu Fu, Jorge Garcés-Ferrer, and Ascensión Doñate-Martínez. 2022. "Palliative Care in Older People with Multimorbidities: A Scoping Review on the Palliative Care Needs of Patients, Carers, and Health Professionals" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 6: 3195. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063195

APA StyleLlop-Medina, L., Fu, Y., Garcés-Ferrer, J., & Doñate-Martínez, A. (2022). Palliative Care in Older People with Multimorbidities: A Scoping Review on the Palliative Care Needs of Patients, Carers, and Health Professionals. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(6), 3195. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063195