Inequalities of Suicide Mortality across Urban and Rural Areas: A Literature Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (1)

- Whether suicides occur more often in rural areas than in urban areas;

- (2)

- Which suicide methods are used most often in urban and rural areas;

- (3)

- What trends there are in suicides across urban and rural areas.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.3. Selection Process

2.4. Data Collection Process

2.5. Quality Assessment of Studies

2.6. Narrative Summary

3. Results

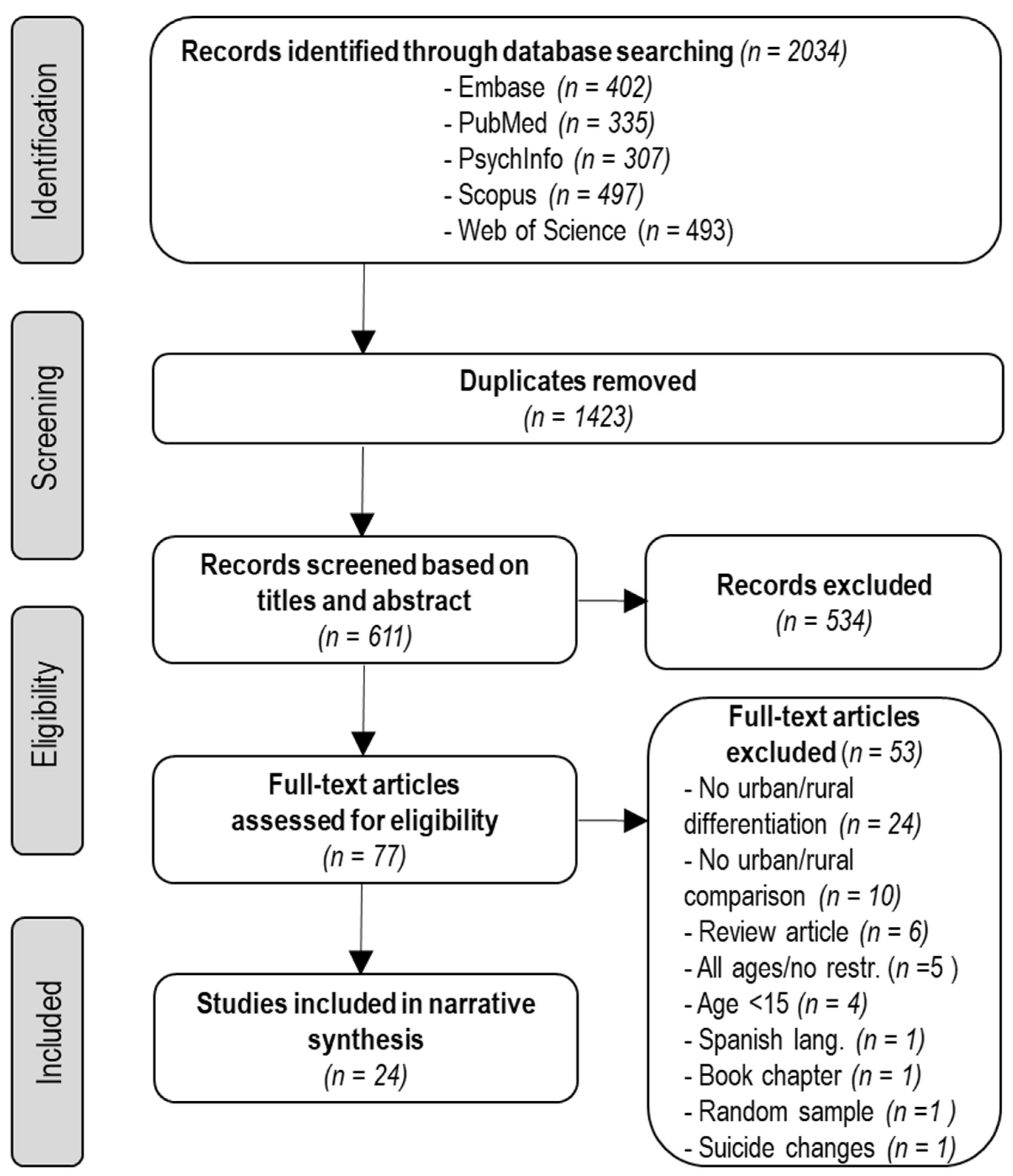

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Differences in Suicide Rates between Urban and Rural Areas

3.4. Methods of Suicide

3.5. Trends over Time

3.6. Risk of Bias

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal Findings

4.2. Possible Explanation and Interpretation of the Findings

4.2.1. Social Integration

4.2.2. Socioeconomic Risk Factors

4.2.3. Availability of Mental Health Services

4.2.4. Availability of Suicide Methods

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

4.4. Implications for Public Health Policy and Practice

4.5. Future Research Priorities

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Naghavi, M. Global, regional, and national burden of suicide mortality 1990 to 2016: Systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. BMJ 2019, 364, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. Suicide Worldwide in 2019: Global Health Estimates; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Oliván, I.; Porras-Segovia, A.; Barrigón, M.L.; Jiménez-Muñoz, L.; Baca-Garcia, E. Theoretical models of suicidal behaviour: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. Eur. J. Psychiatry 2021, 35, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Page, A.; Martin, G.; Taylor, R. Attributable risk of psychiatric and socio-economic factors for suicide from individual-level, population-based studies: A systematic review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 72, 608–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turecki, G.; Brent, D.A. Suicide and suicidal behaviour. Lancet 2016, 387, 1227–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forte, A.; Vichi, M.; Ghirini, S.; Orri, M.; Pompili, M. Trends and ecological results in suicides among Italian youth aged 10–25 years: A nationwide register study. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 282, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventriglio, A.; Torales, J.; Castaldelli-Maia, J.M.; De Berardis, D.; Bhugra, D. Urbanization and emerging mental health issues. CNS Spectr. 2021, 26, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontanella, C.A.; Hiance-Steelesmith, D.L.; Phillips, G.S.; Bridge, J.A.; Lester, N.; Sweeney, H.A.; Campo, J.V. Widening rural-urban disparities in youth suicides, United States, 1996–2010. JAMA Pediatr. 2015, 169, 466–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, E.; Hanley, S.J.B.; Sato, Y.; Saijo, Y. Geography of suicide in Japan: Spatial patterning and rural–urban differences. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2021, 56, 731–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helbich, M.; Blüml, V.; de Jong, T.; Plener, P.L.; Kwan, M.-P.; Kapusta, N.D. Urban-rural inequalities in suicide mortality: A comparison of urbanicity indicators. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2017, 16, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanamori, M.; Kondo, N.; Juárez, S.P.; Cederström, A.; Stickley, A.; Rostila, M. Does increased migration affect the rural-urban divide in suicide? A register-based repeated cohort study in Sweden from 1991 to 2015. Popul. Space Place 2021, 28, e2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapusta, N.D.; Zorman, A.; Etzersdorfer, E.; Ponocny-Seliger, E.; Jandl-Jager, E.; Sonneck, G. Rural-urban differences in Austrian suicides. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2008, 43, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, K.A.; Leyland, A.H. Urban/rural inequalities in suicide in Scotland, 1981–1999. Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 60, 2877–2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Xiang, Y.-T.; Cai, Z.-J.; Li, S.-R.; Xiang, Y.-Q.; Guo, H.-L.; Hou, Y.-Z.; Li, Z.-B.; Li, Z.-J.; Tao, Y.-F.; et al. Lifetime prevalence of suicidal ideation, suicide plans and attempts in rural and urban regions of Beijing, China. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2009, 43, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Middleton, N.; Sterne, J.A.; Gunnell, D. The geography of despair among 15-44-year-old men in England and Wales: Putting suicide on the map. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2006, 60, 1040–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Taylor, R.; Page, A.; Morrell, S.; Harrison, J.; Carter, G. Social and psychiatric influences on urban-rural differentials in Australian suicide. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 2005, 35, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, P.S.F.; Callanan, C.; Yuen, H.P. Urban/rural and gender differentials in suicide rates: East and West. J. Affect. Disord. 2000, 57, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, R.; Rehm, J.; de Oliveira, C.; Gozdyra, P.; Kurdyak, P. Rurality and risk of suicide attempts and death by suicide among people living in four English-speaking high-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Can. J. Psychiatry 2020, 65, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.Z.; Katikireddi, S.V. Urban-rural inequalities in suicide among elderly people in China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Equity Health 2019, 18, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagedoorn, P.; Groenewegen, P.P.; Roberts, H.; Helbich, M. Is suicide mortality associated with neighbourhood social fragmentation and deprivation? A Dutch register-based case-control study using individualised neighbourhoods. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2020, 74, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Robbins, D.R.; Alessi, N.E. Depressive symptoms and suicidal behavior in adolescents. Am. J. Psychiatry 1985, 142, 588–592. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, A.; Breier, A.; Doran, A.R.; Pickar, D. Life events in depression. Relationship to subtypes. J. Affect. Disord. 1985, 9, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusé, T. Suicide and culture in Japan: A study of seppuku as an institutionalized form of suicide. Soc. Psychiatry 1980, 15, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, J.; Cox, W.M. An economic interpretation of suicide cycles in Japan. Contemp. Econ. Policy 2008, 26, 162–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kuroki, M. Suicide and unemployment in Japan: Evidence from municipal level suicide rates and age-specific suicide rates. J. Soc. Econ. 2010, 39, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searles, V.B.; Valley, M.A.; Hedegaard, H.; Betz, M.E. Suicides in urban and rural counties in the United States, 2006–2008. Crisis 2014, 35, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, J.K. A review of the literature on rural suicide: Risk and protective factors, incidence, and prevention. Crisis J. Crisis Interv. Suicide Prev. 2006, 27, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, J.K.; Cukrowicz, K.C. Suicide in rural areas: An updated review of the literature. J. Rural Ment. Health 2014, 38, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wells, G.; Shea, B.; O’Connell, D.; Robertson, J.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analysis. Available online: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (accessed on 1 February 2022).

- Chang, S.S.; Gunnell, D.; Wheeler, B.W.; Yip, P.; Sterne, J.A.C. The evolution of the epidemic of charcoal-burning suicide in Taiwan: A spatial and temporal analysis. PLoS Med. 2010, 7, e1000212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cheung, Y.T.D.; Spittal, M.J.; Pirkis, J.; Yip, P.S.F. Spatial analysis of suicide mortality in Australia: Investigation of metropolitan-rural-remote differentials of suicide risk across states/territories. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 75, 1460–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J.F.; Blow, F.C.; Ignacio, R.V.; Ilgen, M.A.; Austin, K.L.; Valenstein, M. Suicide among patients in the Veterans Affairs Health System: Rural-urban differences in rates, risks, and methods. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, S111–S117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, A.; Morrell, S.; Taylor, R.; Dudley, M.; Carter, G. Further increases in rural suicide in young Australian adults: Secular trends, 1979–2003. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 65, 442–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.; Barnett, R.; Jones, I. Have urban/rural inequalities in suicide in New Zealand grown during the period 1980–2001? Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 65, 1807–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, S.S.; Lu, T.H.; Sterne, J.A.C.; Eddleston, M.; Lin, J.J.; Gunnell, D. The impact of pesticide suicide on the geographic distribution of suicide in Taiwan: A spatial analysis. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Saunderson, T.; Haynes, R.; Langford, I.H. Urban-rural variations in suicides and undetermined deaths in England And Wales. J. Public Health 1998, 20, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shiner, B.; Peltzman, T.; Cornelius, S.L.; Gui, J.; Forehand, J.; Watts, B.V. Recent trends in the rural–urban suicide disparity among veterans using VA health care. J. Behav. Med. 2020, 44, 492–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesonen, T.M.; Hintikka, J.; Karkola, K.O.; Saarinen, P.I.; Antikainen, M.; Lehtonen, J. Male suicide mortality in eastern Finland—Urban-rural changes during a 10-year period between 1988 and 1997. Scand. J. Public Health 2001, 29, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrows, S.; Auger, N.; Gamache, P.; Hamel, D. Leading causes of unintentional injury and suicide mortality in Canadian adults across the urban-rural continuum. Public Health Rep. 2013, 128, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Caldwell, T.M.; Jorm, A.F.; Dear, K.B.G. Suicide and mental health in rural, remote and metropolitan areas in Australia. Med. J. Aust. 2004, 181, S10–S14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantor, C.H.; Coory, M. Is there a rural suicide problem? Aust. J. Public Health 1993, 17, 382–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carriere, D.E.; Marshall, M.I.; Binkley, J.K. Response to economic shock: The impact of recession on rural-urban suicides in the United States. J. Rural Health 2019, 35, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelleher, M.J.; Corcoran, P.; Keeley, H.S.; Chambers, D.; Williamson, E.; McAuliffe, C.; Burke, U.; Byrne, S. Differences in Irish urban and rural suicide rates, 1976–1994. Arch. Suicide Res. 2002, 6, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrell, S.; Taylor, R.; Slaytor, E.; Ford, P. Urban and rural suicide differentials in migrants and the Australian-born, New South Wales, Australia 1985–1994. Soc. Sci. Med. 1999, 49, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.; Lester, D. Rural and urban suicide in South Korea. Psychol. Rep. 2012, 111, 495–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razvodovsky, Y.; Stickley, A. Suicide in urban and rural regions of Belarus, 1990–2005. Public Health 2009, 123, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sankaranarayanan, A.; Carter, G.; Lewin, T. Rural-urban differences in suicide rates for current patients of a public mental health service in Australia. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 2010, 40, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, G.K.; Siahpush, M. Increasing rural-urban gradients in US suicide mortality, 1970–1997. Am. J. Public Health 2002, 92, 1161–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Guo, X.; Zhang, J.; Jia, C.; Xu, A. Suicide rates in Shandong, China, 1991–2010: Rapid decrease in rural rates and steady increase in male-female ratio. J. Affect. Disord. 2013, 146, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Watanabe, N.; Hasegawa, K.; Yoshinaga, Y. Suicide in later life in Japan: Urban and rural differences. Int. Psychogeriatr. 1995, 7, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrows, S.; Laflamme, L.; Vaez, M. Sex-specific suicide mortality in the South African urban context: The role of age, race, and geographical location. Scand. J. Public Health 2007, 35, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durkheim, É. Suicide: A Study in Sociology; Free Press: Glencoe, IL, USA, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Faupel, C.E.; Kowalski, G.S.; Starr, P.D. Sociology one law, religion and suicide in the urban context. J. Sci. Study Relig. 1987, 26, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masumura, W.T. Social integration and suicide: A test of Durkheim’s theory. Behav. Sci. Res. 1977, 12, 251–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuser, C.; Howe, J. The relation between social isolation and increasing suicide rates in the elderly. Qual. Ageing Older Adults 2018, 20, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duberstein, P.R.; Conwell, Y.; Conner, K.R.; Eberly, S.; Evinger, J.S.; Caine, E.D. Poor social integration and suicide: Fact or artifact? A case-control study. Psychol. Med. 2004, 34, 1331–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helbich, M.; O’Connor, R.C.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.; Hagedoorn, P. Greenery exposure and suicide mortality later in life: A longitudinal register-based case-control study. Environ. Int. 2020, 143, 105982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helbich, M.; Plener, P.L.; Hartung, S.; Blüml, V. Spatiotemporal suicide risk in Germany: A longitudinal study 2007–11. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 7673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rehkopf, D.H.; Buka, S.L. The association between suicide and the socio-economic characteristics of geographical areas: A systematic review. Psychol. Med. 2006, 36, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns, J.-M.; Graham, E.; Bambra, C. Area-level socioeconomic disadvantage and suicidal behaviour in Europe: A systematic review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 192, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kapusta, N.D.; Posch, M.; Niederkrotenthaler, T.; Fischer-Kern, M.; Etzersdorfer, E.; Sonneck, G. Availability of mental health service providers and suicide rates in Austria: A nationwide study. Psychiatr. Serv. 2010, 61, 1198–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesney, E.; Goodwin, G.M.; Fazel, S. Risks of all-cause and suicide mortality in mental disorders: A meta-review. World Psychiatry 2014, 13, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Judd, F.; Cooper, A.-M.; Fraser, C.; Davis, J. Rural suicide—People or place effects? Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2006, 40, 208–216. [Google Scholar]

- Burnley, I.H. Socioeconomic and spatial differentials in mortality and means of committing suicide in New South Wales, Australia, 1985–1991. Soc. Sci. Med. 1995, 41, 687–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettrone, K.; Curtin, S.C. Urban-Rural Differences in Suicide Rates, by Sex and Three Leading Methods: United States, 2000–2018; US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; pp. 1–8.

- Kong, Y.; Zhang, J. Access to farming pesticides and risk for suicide in Chinese rural young people. Psychiatry Res. 2010, 179, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cha, E.S.; Khang, Y.-H.; Lee, W.J. Mortality from and incidence of pesticide poisoning in South Korea: Findings from national death and health utilization data between 2006 and 2010. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e95299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chaparro-Narváez, P.; Díaz-Jiménez, D.; Castañeda-Orjuela, C. The trend in mortality due to suicide in urban and rural areas of Colombia, 1979–2014. Biomedica 2019, 39, 339–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waffenschmidt, S.; Knelangen, M.; Sieben, W.; Bühn, S.; Pieper, D. Single screening versus conventional double screening for study selection in systematic reviews: A methodological systematic review. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2019, 19, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, W.S. Ecological correlations and the behavior of individuals. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2009, 38, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Openshaw, S. The modifiable areal unit problem. Quant. Geogr. A Br. View 1981, 128, 60–69. [Google Scholar]

- Hagedoorn, P.; Helbich, M. Longitudinal exposure assessments of neighbourhood effects in health research: What can be learned from people’s residential histories? Health Place 2021, 68, 102543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagedoorn, P.; Helbich, M. Longitudinal effects of physical and social neighbourhood change on suicide mortality: A full population cohort study among movers and non-movers in the Netherlands. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 294, 114690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helbich, M. Toward dynamic urban environmental exposure assessments in mental health research. Environ. Res. 2018, 161, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokela, M. Are neighborhood health associations causal? A 10-year prospective cohort study with repeated measurements. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 180, 776–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- OECD. Functional Urban Areas by Country. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/cfe/regional-policy/functionalurbanareasbycountry.htm (accessed on 1 February 2022).

- Davoudi, M.; Barjasteh-Askari, F.; Amini, H.; Lester, D.; Mahvi, A.H.; Ghavami, V.; Ghalhari, M.R. Association of suicide with short-term exposure to air pollution at different lag times: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 771, 144882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Population | Region | Research Design | Indicator | N | Study Period | Age Group | Suicide Rate (per 100,000 People) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rural | Urban | Rural Women | Urban Women | Rural Men | Urban Men | ||||||||

| [39] * | All | Canada | Cohort | Suicide rates | 2,735,152 | 1991–2001 | ≥25 | - | - | 7.5 | 6.0 | 31.4 | 18.6 |

| [40] | All | Australia | Ecological | Suicide rates | 6 states | 1997–2000 | ≥20 | - | - | 5.7 | 5.6 | 24.0 | 20.2 |

| [41] * | All | Queensland, Australia | Ecological | Suicide rates | 1 state | 1986–1990 | 15–19 | - | - | 6.5 | 1.7 | 24.1 | 18.9 |

| 20–29 | - | 4.2 | 10.2 | 29.6 | 33.2 | ||||||||

| [42] ** | All | United States | Ecological | County mortality rates | 50 states | 2002 | ≥20 | 17.2 | 13.2 | - | - | - | - |

| 2016 | 23.2 | 15.8 | - | - | - | - | |||||||

| [30] | All | Taiwan | Ecological | Suicide rates | 358 districts | 1999–2001 | ≥15 | - | - | 14.3 | 11.1 | 31.4 | 21.3 |

| 2002–2004 | - | - | 15.1 | 12.8 | 30.4 | 27.2 | |||||||

| 2005–2007 | - | - | 17.3 | 15.1 | 37.8 | 31.5 | |||||||

| [35] * | All | Taiwan | Ecological | Suicide rates | 358 districts | 2002–2009 | ≥15 | 26.3 | 21.2 | - | - | - | - |

| [31] | All | Australia | Ecological | Suicide rates | 6 states | 2004–2008 | 15–19 | - | - | 4.56 | 4.60 | 18.19 | 15.67 |

| [43] *,** | All | Ireland | Ecological | Suicide rates | 27 counties | 1976 | ≥15 | - | - | 3.5 | 4.5 | 8.0 | 7.5 |

| 1993 | - | - | 4.5 | 4.5 | 20.0 | 15.5 | |||||||

| [13] *,** | All | Australia | Ecological | Suicide rates | 32 council areas | 1981–1984 | 15–39 | - | - | 8.8 | 7.5 | 29.0 | 20.0 |

| 1997–1999 | - | - | 13.2 | 10.5 | 45.0 | 36.5 | |||||||

| [32] | Veterans Affairs users | United States | Ecological | Suicide rates | 50 states | 2004–2005 | ≥18 | 38.76 | 31.45 | - | - | - | - |

| 2007–2008 | 39.62 | 32.44 | - | - | - | - | |||||||

| [44] * | Migrants | New South Wales, Australia | Ecological | Suicide rates | 1 state | 1985–1994 | ≥15 | - | - | 7.9 | 6.5 | 38.2 | 19.9 |

| [33] * | All | Australia | Ecological | Suicide rates | 6 states | 1979–1983 | - | - | 5.3 | 8.6 | 19.2 | 19.5 | |

| 1984–1988 | - | - | 6.3 | 7.6 | 23.7 | 21.8 | |||||||

| 1989–1993 | - | - | 5.4 | 7.2 | 22.9 | 22.9 | |||||||

| 1994–1998 | - | - | 5.9 | 7.1 | 24.2 | 24.2 | |||||||

| 1999–2003 | - | - | 6.1 | 6.8 | 22.4 | 22.4 | |||||||

| [45] | All | South Korea | Ecological | Suicide rates | 9 provinces | 2005 | ≥15 | 35.4 | 16.3 | 26.1 | 20.0 | 63.3 | 40.3 |

| [34] *,** | All | New Zealand | Ecological | Suicide rates | 10 provinces | 1981 | ≥15 | - | - | 6.0 | 4.0 | 11.8 | 14.6 |

| 2000 | - | - | 5.3 | 5.5 | 21.0 | 19.5 | |||||||

| [38] * | Males | Eastern Finland | Ecological | Suicide rates | 1 province | 1988 | ≥15 | - | - | - | - | 84.0 | 53.0 |

| 1992 | - | - | - | - | 53.0 | 52.0 | |||||||

| 1997 | - | - | - | - | 80.0 | 36.0 | |||||||

| [46] * | All | Belarus | Ecological | Suicide rates | 6 oblasts | 1990 | ≥15 | - | - | 8.69 | 7.74 | 50.48 | 31.96 |

| 1995 | - | - | 10.02 | 9.48 | 80.08 | 52.27 | |||||||

| 2000 | - | - | 11.73 | 8.58 | 99.68 | 50.33 | |||||||

| 2005 | - | - | 11.67 | 6.78 | 94.73 | 38.79 | |||||||

| [47] * | Mental Health Service | Australia | Ecological | Suicide rates | 580 | 2003–2007 | ≥15 | 3.1 | 1.1 | - | - | - | - |

| [36] | All | England and Wales | Ecological | Suicide rates | 311 districts | 1989–1992 | ≥15 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| [37] * | Veterans Affairs users | United States | Cohort | Suicide rates | 6,120,355 | 2003–2005 | ≥18 | 30.6 | 27.2 | 13.1 | 9.6 | 31.6 | 29.0 |

| 2006–2008 | 32.5 | 27.8 | 8.6 | 9.6 | 34.0 | 29.7 | |||||||

| 2009–2011 | 33.2 | 29.1 | 13.8 | 13.1 | 34.4 | 30.9 | |||||||

| 2012–2014 | 34.8 | 30.3 | 18.1 | 11.9 | 35.9 | 32.5 | |||||||

| 2015–2017 | 35.6 | 31.0 | 16.8 | 12.4 | 37.0 | 33.3 | |||||||

| [48] * | All | Canada | Ecological | Suicide rates | 3103 counties | 1970–1974 | ≥15 | - | - | 4.13 | 8.70 | 20.71 | 19.84 |

| 1975–1979 | - | - | 5.31 | 7.61 | 21.31 | 20.36 | |||||||

| 1980–1984 | - | - | 4.58 | 6.00 | 34.24 | 19.17 | |||||||

| 1985–1989 | - | - | 4.43 | 5.25 | 24.57 | 19.58 | |||||||

| 1990–1994 | - | - | 4.14 | 4.57 | 25.73 | 18.74 | |||||||

| 1995–1997 | - | - | 4.01 | 4.05 | 26.88 | 17.45 | |||||||

| [49] * | All | Shandong, China | Ecological | Suicide rates | 19 counties | 1991–1995 | ≥15 | 40.02 | 6.62 | 40.75 | 6.88 | 39.26 | 6.58 |

| 1996–2000 | 31.16 | 7.71 | 30.28 | 6.87 | 32.04 | 8.82 | |||||||

| 2001–2005 | 21.24 | 4.95 | 18.99 | 3.97 | 23.55 | 5.87 | |||||||

| 2006–2010 | 19.00 | 5.32 | 17.33 | 4.73 | 20.65 | 5.90 | |||||||

| [16] * | All | Australia | Ecological | Suicide rates | 6 states | 1996–1998 | ≥20 | - | - | 7.3 | 7.2 | 34.7 | 28.2 |

| [50] | All | Japan | Ecological | Suicide rates | 47 prefectures | 1988 | ≥65 | 240.4 | 38.3 | 277.3 | 26.5 | 185.0 | 53.9 |

| [17] | All | Australia | Ecological | Suicide rates | 1 country | 1991–1996 | ≥15 | - | - | 5.4 | 6.7 | 30.5 | 25.7 |

| [17] | All | Beijing | Ecological | Suicide rates | 1 city | 1991–1996 | ≥15 | - | - | 17.1 | 6.0 | 16.3 | 5.7 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Casant, J.; Helbich, M. Inequalities of Suicide Mortality across Urban and Rural Areas: A Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2669. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052669

Casant J, Helbich M. Inequalities of Suicide Mortality across Urban and Rural Areas: A Literature Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(5):2669. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052669

Chicago/Turabian StyleCasant, Judith, and Marco Helbich. 2022. "Inequalities of Suicide Mortality across Urban and Rural Areas: A Literature Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 5: 2669. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052669

APA StyleCasant, J., & Helbich, M. (2022). Inequalities of Suicide Mortality across Urban and Rural Areas: A Literature Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(5), 2669. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052669